Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pisco Formation

View on WikipediaThe Pisco Formation is a geologic formation located in Peru, on the southern coastal desert of Ica and Arequipa. The approximately 640 metres (2,100 ft) thick formation was deposited in the Pisco Basin, spanning an age from the Late Miocene up to the Early Pliocene, roughly from 9.6 to 4.5 Ma. The tuffaceous sandstones, diatomaceous siltstones, conglomerates and dolomites were deposited in a lagoonal to near-shore environment, in bays similar to other Pacific South American formations as the Bahía Inglesa and Coquimbo Formations of Chile.

Key Information

The Pisco Formation is considered one of the most important Lagerstätten sites,[2][3] based on the large amount of exceptionally preserved marine fossils, including sharks (most notably megalodon), birds including penguins, whales and dolphins, marine crocodiles, and Thalassocnus, a marine giant sloths.[4]

Other famous fossils from this site include the giant raptorial sperm whale Livyatan,[5] the sperm whale relative Acrophyseter, and the walrus-like dolphin Odobenocetops.[6]

Description

[edit]The Pisco Formation of the Pisco Basin consists of tuffaceous sandstones, diatomaceous yellow to gray siltstones and a basal conglomerate.[7] The formation is deposited from Pisco in the north to Yauca in the south. The northern portion is known as the Ocucaje Area and the southern part as the Sacaco Area.[8] The total thickness of the formation is estimated at 640 metres (2,100 ft).[9] The formation unconformably overlies the Chilcatay and Caballas Formations.

Paleobiota of the Pisco Formation

[edit]The Pisco Formation has provided a rich resource of marine fauna, including marine mammals like cetaceans and seals, large fishes, reptiles, and penguins.[10] It is also one of the richest sites in the world for fossil cetaceans, with close to 500 examples being found in the formation.[11]

The oldest fossils of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus (T. antiquus) come from the Aguada de Lomas horizon of the Pisco Formation and were dated at roughly 7 Ma. The youngest specimen (T. carolomartini) was found in the Sacaco horizon and dated to approximately 3 Ma.[12] Thalassocnus was preyed upon by the probable apex predators of the environment, Livyatan and megalodon.[13][14] The youngest strata belonging to the formation have been dated at 2 Ma, corresponding to the Early Pleistocene (Uquian). Fossils of the modern Humboldt penguin were found in these deposits at the Yauca locality.[15]

Birds

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Locality | Materials | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciconiidae indet. | Gen. et sp. indet. | A stork | ||||

| Fulmarus | Indet. sp. | A petrel | ||||

| Morus | M. peruvianus | Sud-Sacaco | A set of limb elements | A relative of living gannets (Sulidae) |  |

|

| Perugyps | P. diazi | Sud-Sacaco | A limb element (right carpometacarpus). | A New World vulture (Cathartidae) | ||

| Pelagornis | Pelagornis sp. | Aguada de Lomas | Proximal carpometacarpus and right humerus ends | A pseudotoothed bird (Pelagornithidae) |  |

|

| Pelecanus | Indet. sp. | A pelican | ||||

| Phalacrocorax | P. aff. bougainvillii | A relative of the Guanay cormorant |  |

|||

| cf. Phalacrocorax sp. | Probable cormorant remains | |||||

| Rhamphastosula | R. aguierrei | Sud-Sacaco West | A cranium skull | A sulid bird with an enlarged beak | ||

| R. ramirezi | Sud-Sacaco West | A skull | ||||

| Spheniscus | S. humbodti | Sud Sacaco | Archaic Humboldt penguin |  |

[15] | |

| S. megarhampus | Sud Sacaco | A partial skeleton | Large-beaked banded penguin |

|

[15] | |

| S. muizoni | Cerro la Bruja | A partial skeleton. | The oldest banded penguin |  |

[24][25] | |

| S. urbinai | Sud-Sacaco West | A partial skeleton (partial skeleton with skull) | A larger banded penguin than S. muizoni |

|

[15] | |

| Sula | S. brandi | Cerro Colorado | A neurocranium lacking interorbital septum, lacrimals, palatines, pterygoids, jugals, quadrates, and right quadratojugal.Proximal portion of the beak, including most of the right dentary and angular. | Relatives of living boobies (Sulidae) |  |

|

| S. magna | Sud Sacaco | A set of limb elements. | ||||

| S. sulita | Sud Sacaco | A limb element (coracoid) |

Fish

[edit]Bony fish

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alosinae | indet. sp. | A type of herring | ||

| Centropomidae | C. aff. Psamoperca | A snook | ||

| Triglidae | indet. sp. | A type of sea robin | ||

| Xiphiidae | indet. sp. | A swordfish | ||

| Sardinops | S. humboldti | A sardine |

Rays

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myliobatis | indet. sp. | A species of eagle ray |  |

Sharks

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Locality | Materials | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcharias | C. taurus | Archaic sand tiger shark | ||||

| Carcharhinus | indet. sp. | A requiem shark | ||||

| Carcharodon | C. carcharias | Archaic great white shark and close relative, respectively |  |

|||

| C. hubbelli | ||||||

| Cosmopolitodus | C. hastalis | The broad-toothed "mako" | ||||

| Hexanchus | H. gigas | A cow shark | ||||

| Isurus | I. oxyrhinchus | Archaic shortfin mako |  |

|||

| Otodus | O. megalodon | The largest of the megatoothed sharks (Otodontidae) and of all fishes |  |

Mammals

[edit]Cetaceans

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Locality | Material | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrophyseter | A. deinodon | Sud-Sacaco | A skull | A small raptorial physeteroid (sperm whale relative) |  |

|

| A. robustus | Cerro la Bruja | A skull | ||||

| Atocetus | A. iquensis | Cero la Bruja | A skull | A small kentriodontid whale |  |

|

| Australithax | A. intermedia | El Jahuay | A long-snouted porpoise (Phocoenidae) | |||

| Balaenoptera | B. siberi | Aguada de Lomas | A partial skeleton | Archaic rorqual (Balaenopteridae) |  |

|

| Belonodelphis | B. peruanus | Cerro la Bruja | A skull | An elongated oceanic dolphin (Delphinidae) | ||

| Brachydelphis | B. jahuayensis | El Jahuay | A partial skull | An early oceanic dolphin (Delphinidae) |  |

|

| B. mazeasi | El Jahuay | A partial skull | ||||

| Brujadelphis | B. ankylorostris | Cerro la Bruja | A skull with complete jaw | A toothed whale of uncertain relation (incertae sedis) | ||

| Hemisyntrachelus | H. oligodon | Sud-Sacaco | A skull | An orca relative | ||

| Incakujira | I. anillodefuego | Aguada de Lomas | A preserved skeleton | A small rorqual (Balaenopteridae) |  |

|

| I. fordycei | Aguada de Lomas | A preserved skeleton | ||||

| Kogia | K. danomurai | Sacaco | A partial skull consisting of partial cranium, preserving the facial and dorsolateral regions of the cranial vault, but lacking most of the rostrum and basicranium | Basal member of Kogia, the genus of pygmy and dwarf sperm whale | ||

| Koristocetus | K. pescei | Aguada de Lomas | A partial skull | A small kogiid | ||

| Livyatan | L. melvillei | Cerro Colorado | A partially preserved skull with teeth and lower jaw | A very large raptorial physeteroid with 36 centimetres (1.18 ft) teeth |  |

|

| Lomacetus | L. ginsburgi | Aguada de Lomas | A porpoise relative (Phocoenidae) | |||

| Mamaziphius | M. reyesi | Cerros la Mama y la Hija | A partial skull consisting of partial cranium lacking most of the rostrum, the zygomatic processes of the squamosal, the occipital condyles and the ear bones | An early beaked whale (Ziphiidae) | ||

| Messapicetus | M. gregarius | Cerro Colorado | A partial skeleton consists of a skull, mandibles, humeri, vertebrae, and scapula | An early beaked whale (Ziphiidae) | ||

| Miocaperea | M. pulchra | Aguada de Lomas | A partial skull | A cetothere whale | ||

| Ninoziphius | N. platyrostris | Sacaco | A partial skeleton | A giant beaked whale-relative |  |

|

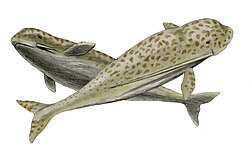

| Odobenocetops | O. leptodon | Sacaco | A preserved skull | A tusked odontocete belonging to its unique family |  |

|

| O. peruvianus | Sacaco | A partial skull | ||||

| Piscobalaena | P. nana | Sud-Sacaco | A skull | A small cetothere |  |

|

| Piscocetus | P. sacaco | Sacaco | A partial skeleton | An extinct cetacean | ||

| Piscolithax | P. aenigmaticus | Aguada de Lomas | A partial skeleton | A porpoise relative (Phocoenidae) |  |

|

| Platyscaphokogia | P. landinii | Cerro Hueco la Zorra, | An incomplete skull lacking the tip of the rostrum and the basicranium. | An early beaked whale (Ziphiidae) | ||

| Pliopontos | P. littoralis | Sud-Sacaco | A partial skull | An early oceanic dolphin (Delphinidae) | ||

| Scaphokogia | S. cochlearis | Aguada de Lomas | An extinct kogiid |

Pinnipeds

[edit]- Seals

| Taxa | Species | Locality | Material | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrophoca | A. longirostirus | Sub-Sacaco | A partial skull. | Archaic southern seal (Monachinae) |  |

|

| Australophoca | A. changorum | Aguada de Lomas | A partial skeleton consists of incomplete right ulna, right radius, right and left humeri, and other unidentified remains. | A phocidae seal. | ||

| Hadrokirus | H. martini | Sub-Sacaco | A partial skull | Archaic southern seal (Monachinae) | ||

| Hydrarctos | H. lomasiensis | Sub-Sacaco | A skull. | A sea lion and fur seal relative (Otariidae) | ||

| Icaphoca | I. choristodon | Cerro La Bruja | A subcomplete skull with associated left and right mandibles, atlas, axis, third, fourth, and fifth cervical vertebrae. | Archaic southern seal (Monachinae) | [49] | |

| Magophoca | M. brevirostris | Cerro la Bruja | A partial skeleton of a male. | Archaic southern seal (Monachinae) | ||

| Piscophoca | P. pacifica | Sub-Sacaco | A partial skull | Archaic southern seal (Monachinae) |  |

Xenarthrans

[edit]- Sloths

| Taxa | Species | Locality | Materials | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalassocnus | T. antiquus | Aguada de Lomas | A partial skeleton including the skull, mandible, and most of the postcranial skeleton. | a semi-aquatic giant sloth inhabiting marine environments |  |

[51] |

| T. carolomartini | Sacaco | An associated skull and mandible and two articulated hands, probably belonging to the same individual. | ||||

| T. littoralis | Sud-Sacaco | A skull with missing jugals. | ||||

| T. natans | Sud-Sacaco | A skull, mandible, and partial skeleton. |

Mollusks

[edit]Bivalves

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosinia | indet. sp. |

Polychaetes

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diplochaetetes | D. mexicanus | A cirratulid bristle worm |  |

Gastropods

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthina | A. obesa | |||

| A. triangularis | ||||

| Concholepas | C. kieneri | |||

| Herminespina | indet. sp. |

Reptiles

[edit]Crocodilians

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Locality | Materials | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eusuchia | indet. sp. | |||||

| Piscogavialis | P. jugaliperforatus | Sacaco | A partial skeleton and a skull. | A gryposuchine (gharial relative) | ||

| P. laberintoensis | Laberinto area, Ladera de Lisson Hill | A complete skull and mandible, along with postcranial elements | ||||

| Sacacosuchus | S. cordovai | Sacaco | A nearly complete skull | A gharial relative (Gavialidae) |

Turtles

[edit]| Taxa | Species | Locality | Materials | Description | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacifichelys | P. urbinai | A sea turtle (Cheloniidae) | ||||

| Chelonia | indet. sp. | Green sea turtle relative |

Correlations

[edit]Laventan

[edit]| Formation | Honda | Honda | Aisol | Cura-Mallín | Pisco | Ipururo | Pebas | Capadare | Urumaco | Inés | Paraná | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin | VSM | Honda | San Rafael | Caldera | Pisco | Ucayali | Amazon | Falcón | Venezuela | Paraná | ||

| Country | ||||||||||||

| Boreostemma | ||||||||||||

| Hapalops | ||||||||||||

| Miocochilius | ||||||||||||

| Theosodon | ||||||||||||

| Xenastrapotherium | ||||||||||||

| Mylodontidae | ||||||||||||

| Sparassodonta | ||||||||||||

| Primates | ||||||||||||

| Rodents | ||||||||||||

| Birds | ||||||||||||

| Terror birds | ||||||||||||

| Reptiles | ||||||||||||

| megalodon | ||||||||||||

| Flora | ||||||||||||

| Insects | ||||||||||||

| Environments | Fluvial | Fluvio-deltaic | Fluvio-lacustrine | Fluvio-deltaic | Fluvial | |||||||

| Volcanic | Yes | |||||||||||

See also

[edit]- Bahía Inglesa Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Chile

- Castilletes Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of the Cocinetas Basin, Colombia

- Cerro Ballena, contemporaneous fossil site of the Bahía Inglesa Formation of Chile

- Coquimbo Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Chile

- Collón Curá Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Patagonia, Argentina

- Honda Group, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Colombia

- Navidad Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Chile

- Pebas Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of the Amazon Basin

- Urumaco, contemporaneous fossil site of the Falcón Basin, Venezuela

References

[edit]- ^ Ochoa, Diana; DeVries, Thomas J.; Quispe, Kelly; Barbosa-Espitia, Angel; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Foster, David A.; Gonzales, Renzo; Revillon, Sidoine; Berrospi, Raul; Pairazamán, Luis; Cardich, Jorge; Perez, Alexander; Romero, Pedro; Urbina, Mario; Carré, Matthieu (2022). "Age and provenance of the Mio-Pleistocene sediments from the Sacaco area, Peruvian continental margin". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 116 103799. Bibcode:2022JSAES.11603799O. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103799. ISSN 0895-9811.

- ^ Brand et al., 2004

- ^ Brand et al., 2011

- ^ a b De Muizon et al., 2003

- ^ a b Lambert et al., 2010

- ^ a b De Muizon & Domning, 2002

- ^ Báez Gómez, 2006, p.65

- ^ Stucchi, 2007, p.368

- ^ Altamirano Sierra, 2013, p.3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Báez Gómez, 2006, p.66

- ^ Poma Porras et al., 2009, p.86

- ^ De Muizon et al., 2004, p.287

- ^ a b Parham & Pyenson, 2010, p.231

- ^ Bianucci et al., 2015, p.543

- ^ a b c d Stucchi, 2007, p.370

- ^ Urbina, M.; Stucchi, M. (2005). "Evidence of a fossil stork (Aves: Ciconiidae) from the Late Miocene of the Pisco Formation, Peru". Bol.Soc.Geol.Peru. 100 (2): 63–66.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Sud Sacaco West at Fossilworks.org

- ^ a b c d e f Sud Sacaco at Fossilworks.org

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Aguada de Loma at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Chávez et al., 2007

- ^ Altamirano Sierra, 2013, p.6

- ^ Yauca at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Stucchi et al., 2016, p.423

- ^ Göhlich, 2007, p.287

- ^ Stucchi, 2007, p.369

- ^ Stucchi et al., 2016, p.419

- ^ a b c d Hueso Blanco at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Carnevale, G.; Pellegrino, L.; Bosio, G.; Bianucci, G.; Collareta, A.; Di Celma, C.; Malinverno, E.; Ramirez Ampuero, A. A.; Tejada-Medina, L.; Chacaltana, C.; Urbina, M.; Marramà, G. (2025). "Fossil sardines from the Pisco Formation (Miocene), Peru: Taxonomy, taphonomy, and paleoecology". Palaeoworld 201049. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2025.201049.

- ^ a b c d Sacaco at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Lambert et al., 2008

- ^ a b c Cerro la Bruja at Fossilworks.org

- ^ De Muizon, 1988, p.131

- ^ De Muizon, 1988, p.88

- ^ Demeré et al., 2005, p.115

- ^ De Muizon, 1988, p.192

- ^ De Muizon, 1988, p.82

- ^ De Muizon, 1988, p.108

- ^ Lambert et al., 2017

- ^ Marx & Kohno, 2016, p.5

- ^ Benites-Palomino, Aldo; Vélez-Juarbe, Jorge; Collareta, Alberto; Ochoa, Diana; Altamirano, Ali; Carré, Matthieu; Laime, Manuel J.; Urbina, Mario; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo (August 2021). Lautenschlager, Stephan (ed.). "Nasal compartmentalization in Kogiidae (Cetacea, Physeteroidea): insights from a new late Miocene dwarf sperm whale from the Pisco Formation". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (3): 1507–1524. Bibcode:2021PPal....7.1507B. doi:10.1002/spp2.1351. ISSN 2056-2799. S2CID 234058681.

- ^ Collareta et al., 2017, p.261

- ^ De Muizon, 1988, p.27

- ^ Bianucci, G.; Benites-Palomino, A. M.; Collareta, A.; Bosio, G.; de Muizon, C.; Merella, M.; Di Celma, C.; Malinverno, E.; Urbina, M.; Lambert, O. (2024). "A new Late Miocene beaked whale (Cetacea, Odontoceti) from the Pisco Formation, and a revised age for the fossil Ziphiidae of Peru" (PDF). Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 63 (1): 21–43. doi:10.4435/BSPI.2024.10.

- ^ Ramassamy, Benjamin; Lambert, Olivier; Collareta, Alberto; Urbina, Mario; Bianucci, Giovanni (2018-01-16). "Description of the skeleton of the fossil beaked whale Messapicetus gregarius searching potential proxies for deep-diving abilities". Fossil Record. 21 (1): 11–32. Bibcode:2018FossR..21...11R. doi:10.5194/fr-21-11-2018. hdl:11568/956055. ISSN 2193-0074.

- ^ Miocaperea pulchra at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Bianucci, G.; Benites-Palomino, A. M.; Collareta, A.; Bosio, G.; de Muizon, C.; Merella, M.; Di Celma, C.; Malinverno, E.; Urbina, M.; Lambert, O. (2024). "A new Late Miocene beaked whale (Cetacea, Odontoceti) from the Pisco Formation, and a revised age for the fossil Ziphiidae of Peru" (PDF). Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 63 (1): 21–43. doi:10.4435/BSPI.2024.10.

- ^ De Muizon, 1988, p.66

- ^ Amson & De Muizon, 2014, p.524

- ^ Dewaele, L.; de Muizon, C. (2025). "Icaphoca choristodon n. gen., n. sp., a new monachine seal (Carnivora, Mammalia) from the Neogene of Peru". Geodiversitas. 47 (11): 465–499. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2025v47a11.

- ^ Dewaele, Leonard & de Muizon, Christian. (2024). A new monachine seal (Monachinae, Phocidae, Mammalia) from the Miocene of Cerro La Bruja (Ica department, Peru). GEODIVERSITAS. 46. 10.5252/geodiversitas2024v46a3.

- ^ McDonald, H. & de Muizon, Christian. (2002). The cranial anatomy of Thalassocnus (Xenarthra, Mammalia), a derived nothrothere from the Neogene of the Pisco Formation (Peru). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22. 349-365. 10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022%5B0349:TCAOTX%5D2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Kočí T, Bosio G, Collareta A, Sanfilippo R, Ekrt B, Urbina M, Malinverno E (2021). "First report on the cirratulid (Annelida, Polychaeta) reefs from the Miocene Chilcatay and Pisco Formations (East Pisco Basin, Peru)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 107 103042. Bibcode:2021JSAES.10703042K. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.103042.

- ^ Zamora-Vega, C.; Romero, P. E.; Urbina Schmitt, M.; Carré, M.; Ochoa, D.; Salas-Gismondi, R. (2025), "Exceptional fossils from Peru and an integrative phylogeny reconcile the evolutionary timing and mode of Gavialis and its kin.", Biology Letters, 21 (8) 20250238: 8, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2025.0238, PMC 12327081, PMID 40767471, retrieved 2025-08-06

- ^ Salas-Gismondi, R.; Ochoa, D.; Jouve, S.; Romero, P.E.; Cardich, J.; Perez, A.; DeVries, T.; Baby, P.; Urbina, M.; Carré, M. (2022-05-11). "Miocene fossils from the southeastern Pacific shed light on the last radiation of marine crocodylians". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 289 (1974) 20220380. doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.0380. PMC 9091840. PMID 35538785.

- ^ Cerro Colorado Pisco at Fossilworks.org

Bibliography

[edit]- Altamirano Sierra, Alí J (2013), "Primer registro de pelicano (Aves: Pelecanidae) para el Mioceno tardio de la formacion Pisco, Peru" (PDF), Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines, 42: 1–12, retrieved 2017-09-04

- Amson, E.; De Muizon, C. (2013), "A new durophagous phocid (Mammalia: Carnivora) from the late Neogene of Peru and considerations on monachine seals phylogeny", Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 12 (5): 523–548, doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.799610, retrieved 2019-03-13

- Báez Gómez, Diego A (2006), "Estudio paleoambiental de la Formación Pisco: Localidad Ocucaje" (PDF), Revista del Instituto de Investigaciones FIGMMG, 9: 64–69, retrieved 2026-01-31

- Bianucci, G.; Di Celma, C.; Landini, W.; Post, K.; Tinelli, C.; de Muizon, C. (2015), "Distribution of fossil marine vertebrates in Cerro Colorado, the type locality of the giant raptorial sperm whale Livyatan melvillei (Miocene, Pisco Formation, Peru)", Journal of Maps, 12 (3): 543–557, doi:10.1080/17445647.2015.1048315, hdl:11568/760494

- Brand, Leonard; Urbina, Mario; Chadwick, Arthur; DeVries, Thomas J.; Esperante, Raul (2011), "A high resolution stratigraphic framework for the remarkable fossil cetacean assemblage of the Miocene/Pliocene Pisco Formation, Peru", Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 31 (4): 414–425, Bibcode:2011JSAES..31..414B, doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2011.02.015

- Brand, Leonard R.; Esperante, Raúl; Chadwick, Arthur V.; Poma Porras, Orlando; Alomía, Merling (2004), "Fossil whale preservation implies high diatom accumulation rate in the Miocene–Pliocene Pisco Formation of Peru", Geology, 32 (2): 165–168, Bibcode:2004Geo....32..165B, doi:10.1130/G20079.1, retrieved 2018-09-07

- Chávez Hoffmeister, Martín Felipe; Stucchi, Marcelo; Urbina Schmitt, Mario (2007), "El registro de Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) y la avifauna neógena del Pacífico sudeste", Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines, 33 (36 (2)): 175–197, doi:10.4000/bifea.3780, retrieved 2019-03-13

- Collareta, Alberto; Lambert, Olivier; de Muizon, Christian; Urbina, Mario; Bianucci, Giovanni (2017), "Koristocetus pescei gen. et sp. nov., a diminutive sperm whale (Cetacea: Odontoceti: Kogiidae) from the late Miocene of Peru" (PDF), Fossil Record, 20 (2): 259–278, Bibcode:2017FossR..20..259C, doi:10.5194/fr-20-259-2017, retrieved 2018-09-07

- Demeré, Thomas A.; Berta, Annalisa; McGowen, Michael R. (2005), "The Taxonomic and Evolutionary History of Fossil and Modern Balaenopteroid Mysticetes" (PDF), Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 12 (1–2): 99–143, doi:10.1007/s10914-005-6944-3, retrieved 2019-03-13

- Göhlich, Ursula B. (2007), "The oldest fossil record of the extant penguin genus Spheniscus — a new species from the Miocene of Peru" (PDF), Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 52: 285–298, retrieved 2019-03-13

- Lambert, Olivier; Bianucci, Giovanni; Urbina, Mario; Geisler, Jonathan H. (2017), "A new inioid (Cetacea, Odontoceti, Delphinida) from the Miocene of Peru and the origin of modern dolphin and porpoise families", Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 179 (4): 919–946

- Lambert, Olivier; Bianucci, Giovanni; Post, Klaas; De Muizon, Christian; Salas Gismondi, Rodolfo; Urbina, Mario; Reumer, Jelle (2010), "The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru", Nature, 466 (7302): 105–108, Bibcode:2010Natur.466..105L, doi:10.1038/nature09067, ISSN 0028-0836, PMID 20596020, retrieved 2017-09-04

- Lambert, Olivier; Bianucci, Giovanni; De Muizon, Christian (2008), "A New Stem-Sperm Whale (Cetacea, Odontoceti, Physeteroidea) from the Latest Miocene of Peru", Comptes Rendus Palevol, 7 (6): 361–369, Bibcode:2008CRPal...7..361L, doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2008.06.002, retrieved 2019-03-13

- Marx, Felix G.; Kohno, Naoki (2016), "A new Miocene baleen whale from the Peruvian desert", Royal Society Open Science, 3 (10): 1–27, Bibcode:2016RSOS....360542M, doi:10.1098/rsos.160542, PMC 5098998, PMID 27853573

- De Muizon, Christian; McDonald, H. Gregory; Salas Gismondi, Rodolfo; Urbina Schmitt, Mario (2004), "The youngest species of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus and a reassessment of the relationships of the nothrothere sloths (Mammalia: Xenarthra)", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 24: 287–297, retrieved 2018-09-05

- De Muizon, Christian; McDonald, H. Gregory; Salas Gismondi, Rodolfo; Urbina, Mario (2003), "A new early species of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Late Miocene of Peru", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 23 (4): 886–894, Bibcode:2003JVPal..23..886D, doi:10.1671/2361-13, ISSN 0272-4634, retrieved 2017-09-04

- De Muizon, Christian; Domning, Daryl P. (2002), "The anatomy of Odobenocetops (Delphinoidea, Mammalia), the walrus-like dolphin from the Pliocene of Peru and its palaeobiological implications", Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 134 (4): 423–452, doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00015.x, ISSN 1096-3642, retrieved 2017-09-04

- De Muizon, C (1988), "Les Vertébrés fossiles de la Formation Pisco (Pérou). Troisième partie: Les Odontocètes (Cetacea, Mammalia) du Miocène", Editions Recherche Sur les Civilisations, 78: 1–244, retrieved 2019-03-13

- Parham, J.F.; Pyenson, N.D. (2010), "New sea turtle from the Miocene of Peru and iterative evolution of feeding ecomorphologies since the Cretaceous" (PDF), Journal of Paleontology, 84 (2): 231–247, Bibcode:2010JPal...84..231P, doi:10.1666/09-077R.1, retrieved 2018-09-07

- Poma Porras, Orlando; Horna Santillán, Edgard; Esperante, Raúl (2009), "Baleen Fósil (Cetacea: mysticeti) en Sedimentos de la Cuenca Marina del Neógeno en la Formación Pisco, al Sur del Perú" (PDF), Revista de Investigación Universitaria, 1: 84–97, retrieved 2017-09-04

- Stucchi, M.; Varas Malca, R.M.; Urbina Schmitt, M. (2016), "New Miocene sulid birds from Peru and considerations on their Neogene fossil record in the Eastern Pacific Ocean" (PDF), Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 61 (2): 417–427, Bibcode:2016AcPaP..61..417S, doi:10.4202/app.00170.2015, retrieved 2018-09-07

- Stucchi, M (2007), "Los pingüinos de la Formación Pisco (Neógeno), Perú" (PDF), 4th European Meeting on the Palaeontology and Stratigraphy of Latin America, Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, 8: 367–373, retrieved 2017-09-04

- Zamora-Vega, C.; Romero, P. E.; Urbina Schmitt, M.; Carré, M.; Ochoa, D.; Salas-Gismondi, R. (2025), "Exceptional fossils from Peru and an integrative phylogeny reconcile the evolutionary timing and mode of Gavialis and its kin.", Biology Letters, 21 (8) 20250238: 8, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2025.0238, PMID 40767471, retrieved 2025-08-06

Further reading

[edit]- A. Alván, J. Apolín, and C. Chacaltana. 2004. Los dientes de Seláceos (Condrichthyies) y su aplicación estratigráfica en Las Lomas de Ullujaya (Ica, Perú). XIII Congreso Peruano de Geología. Resúmenes Extendidos 595–598

- A. Collareta, O. Lambert, W. Landini, C. Di Celma, E. Malinverno, R. Varas-Malca, M. Urbina and G. Bianucci. 2017. Did the giant extinct shark Carcharocles megalodon target small prey? Bite marks on marine mammal remains from the late Miocene of Peru. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 469:84-91

- R. Esperante, L. Brand, K. E. Nick, O. Poma, and M. Urbina. 2008. Exceptional occurrence of fossil baleen in shallow marine sediments of the Neogene Pisco Formation, Southern Peru. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 257:344-360

- A. Gioncada, A. Collareta, K. Gariboldi, O. Lambert, C. Di Clema, E. Bonaccorsi, M. Urbina and G. Bianucci. 2016. Inside baleen: Exceptional microstructure preservation in a late Miocene whale skeleton from Peru. Geology

- C. S. Gutstein, M. A. Cozzuol, A. O. Vargas, M. E. Suarez, C. L. Schultz and D. Rubilar-Rogers. 2009. Patterns of skull variation of Brachydelphis (Cetacea, Odontoceti) from the Neogene of the Southeastern Pacific. Journal of Mammalogy 90(2):504-519

- O. Lambert, A. Collareta, W. Landini, K. Post, B. Ramanssamy, C. Di Celma, M. Urbina and G. Bianucci. 2015. No deep diving: evidence of predation on epipelagic fish for a stem beaked whale from the Late Miocene of Peru. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 282:20151530

- J. Machare, T. DeVries, and E. Fourtanier. 1988. Oligo-Miocene transgression along the Pacific margin of South America: new paleontological and geological evidence from the Pisco basin (Peru). Géodyynamique 3(1–2):25-37

- R. Marocco and C. de Muizon. 1988. Los vertebrados del Neogeno de La Costa Sur del Perú: Ambiente sedimentario y condiciones de fosilización. Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines 17(2):105-117

- C. de Muizon and D. P. Domning. 1985. The first records of fossil sirenians in the southeastern Pacific Ocean. Bulletin du Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle. Section C: Sciences de la Terre: Paléontologie, Géologie, Minéralogie, Paris: Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle 7(3):189-213

- C. de Muizon. 1983. Pliopontos littoralis un nouveau Platanistidae Cetacea du Pliocene de la cote peruvienne. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences Paris Série II (296)1101-1104

- C. de Muizon. 1978. Arctocephalus (Hydrarctos) lomasiensis, subgen. nov. et nov sp., un nouvel Otariidae du Mio-Pliocene de Sacaco. Bulletin de l'Institute Français d'Études Andines 7(3–4):169-189

- M. Urbina and M. Stucchi. 2005. Los cormoranes (Aves: Phalacrocoracidae) del Mio-Plioceno de la Formacion Pisco, Peru. Boletin de la Sociedad Geologica del Peru 99:41-49

- R. M. Varas Malca and A. Valenzuela Toro. 2011. A basal monachine seal from the middle Miocene of the Pisco Formation, Peru. Ameghiniana 48(4):R216-R217

- T. J. DeVries. 2008. Pliocene and Pleistocene Fissurella Bruguiére, 1789 (Gastropoda: Fissurellidae) from Southern Peru. The Veliger 50(2):129-148

- T. J. DeVries. 2007. Cenozoic Turritellidae (Gastropoda) from southern Peru. Journal of Paleontology 81(2):331-351

- T. J. DeVries, L. T. Groves, and M. Urbina. 2006. A new early Miocene Muracypraea Woodring, 1957 (Gastropoda: Cypraeidae) from the Pisco Basin of southern Peru. The Nautilus 120(3):101-105

- T. J. DeVries. 2003. Acanthina Fischer von Waldheim, 1807 (Gastropoda: Muricidae), an ocenebrine genus endemic to South America. The Veliger 46(4):332-350

- T. J. DeVries. 1997. Neogene Ficus (Mesogastropoda: Ficidae) from the Pisco Basin (Peru). Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica de Perú 86:11-18