Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stomach

View on Wikipedia| Stomach | |

|---|---|

Sections of the human stomach | |

Scheme of digestive tract, with stomach in red | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Foregut |

| System | Digestive system |

| Artery | Right gastric artery, left gastric artery, right gastro-omental artery, left gastro-omental artery, short gastric arteries |

| Vein | Right gastric vein, left gastric vein, right gastroepiploic vein, left gastroepiploic vein, short gastric veins |

| Nerve | Celiac ganglia, vagus nerve[1] |

| Lymph | Celiac lymph nodes[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ventriculus, stomachus |

| Greek | στόμαχος |

| MeSH | D013270 |

| TA98 | A05.5.01.001 |

| TA2 | 2901 |

| FMA | 7148 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

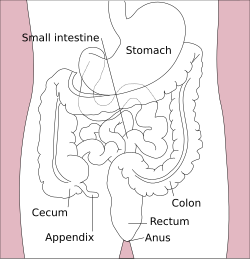

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is gaster which is used as gastric in medical terms related to the stomach.[3] The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach is involved in the gastric phase of digestion, following the cephalic phase in which the sight and smell of food and the act of chewing are stimuli. In the stomach a chemical breakdown of food takes place by means of secreted digestive enzymes and gastric acid. It also plays a role in regulating gut microbiota, influencing digestion and overall health.[4]

The stomach is located between the esophagus and the small intestine. The pyloric sphincter controls the passage of partially digested food (chyme) from the stomach into the duodenum, the first and shortest part of the small intestine, where peristalsis takes over to move this through the rest of the intestines.

Structure

[edit]In the human digestive system, the stomach lies between the esophagus and the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). It is in the left upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity. The top of the stomach lies against the diaphragm. Lying behind the stomach is the pancreas. A large double fold of visceral peritoneum called the greater omentum hangs down from the greater curvature of the stomach. Two sphincters keep the contents of the stomach contained; the lower esophageal sphincter (found in the cardiac region), at the junction of the esophagus and stomach, and the pyloric sphincter at the junction of the stomach with the duodenum.

The stomach is surrounded by parasympathetic (inhibitor) and sympathetic (stimulant) plexuses (networks of blood vessels and nerves in the anterior gastric, posterior, superior and inferior, celiac and myenteric), which regulate both the secretory activity of the stomach and the motor (motion) activity of its muscles.

The stomach is distensible, and can normally expand to hold about one litre of food.[5] The shape of the stomach depends upon the degree of its distension and that of surrounding viscera, e.g. the colon.[4] When empty, the stomach is somewhat J-shaped; when partially distended, it becomes pyriform in shape. In obese persons, it is more horizontal.[4] In a newborn human baby the stomach will only be able to hold about 30 millilitres. The maximum stomach volume in adults is between 2 and 4 litres,[6][7] although volumes of up to 15 litres have been observed in extreme circumstances.[8]

Sections

[edit]

The human stomach can be divided into four sections, beginning at the cardia followed by the fundus, the body and the pylorus.[9][10]

- The gastric cardia is where the contents of the esophagus empty from the gastroesophageal sphincter into the cardiac orifice, the opening into the gastric cardia.[11][10] A cardiac notch at the left of the cardiac orifice, marks the beginning of the greater curvature of the stomach. A horizontal line across from the cardiac notch gives the dome-shaped region called the fundus.[10] The cardia is a very small region of the stomach that surrounds the esophageal opening.[10]

- The fundus (from Latin 'bottom') is formed in the upper curved part.[12]

- The body or corpus is the main, central region of the stomach.[12]

- The pylorus (from Greek 'gatekeeper') connects the stomach to the duodenum at the pyloric sphincter. The pyloric antrum opens to the body of the stomach.[12]

The cardia is defined as the region following the "z-line" of the gastroesophageal junction, the point at which the epithelium changes from stratified squamous to columnar. Near the cardia is the lower esophageal sphincter.[11]

Anatomical proximity

[edit]The stomach bed refers to the structures upon which the stomach rests in mammals.[13][14] These include the tail of the pancreas, splenic artery, left kidney, left suprarenal gland, transverse colon and its mesocolon, and the left crus of diaphragm, and the left colic flexure. The term was introduced around 1896 by Philip Polson of the Catholic University School of Medicine, Dublin. However this was brought into disrepute by surgeon anatomist J Massey.[15][16][17]

Blood supply

[edit]

The lesser curvature of the human stomach is supplied by the right gastric artery inferiorly and the left gastric artery superiorly, which also supplies the cardiac region. The greater curvature is supplied by the right gastroepiploic artery inferiorly and the left gastroepiploic artery superiorly. The fundus of the stomach, and also the upper portion of the greater curvature, is supplied by 5-7 short gastric arteries, which arise from the splenic artery.[4]

Lymphatic drainage

[edit]The two sets of gastric lymph nodes drain the stomach's tissue fluid into the lymphatic system through the intestinal lymph trunk, to the cisterna chyli.[4]

Microanatomy

[edit]Wall

[edit]

Like the other parts of the gastrointestinal wall, the human stomach wall from inner to outer, consists of a mucosa, submucosa, muscular layer, subserosa and serosa.[19]

The inner part of the stomach wall is the gastric mucosa a mucous membrane that forms the lining of the stomach. The membrane consists of an outer layer of columnar epithelium, a lamina propria, and a thin layer of smooth muscle called the muscularis mucosa. Beneath the mucosa lies the submucosa, consisting of fibrous connective tissue.[20] Meissner's plexus is in this layer interior to the oblique muscle layer.[21]

Outside of the submucosa lies the muscular layer. It consists of three layers of muscular fibres, with fibres lying at angles to each other. These are the inner oblique, middle circular, and outer longitudinal layers.[22] The presence of the inner oblique layer is distinct from other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, which do not possess this layer.[23] The stomach contains the thickest muscular layer consisting of three layers, thus maximum peristalsis occurs here.

- The inner oblique layer: This layer is responsible for creating the motion that churns and physically breaks down the food. It is the only layer of the three which is not seen in other parts of the digestive system. The antrum has thicker skin cells in its walls and performs more forceful contractions than the fundus.

- The middle circular layer: At this layer, the pylorus is surrounded by a thick circular muscular wall, which is normally tonically constricted, forming a functional (if not anatomically discrete) pyloric sphincter, which controls the movement of chyme into the duodenum. This layer is concentric to the longitudinal axis of the stomach.

- The myenteric plexus (Auerbach's plexus) is found between the outer longitudinal and the middle circular layer and is responsible for the innervation of both (causing peristalsis and mixing).

The outer longitudinal layer is responsible for moving the semi-digested food towards the pylorus of the stomach through muscular shortening.

To the outside of the muscular layer lies a serosa, consisting of layers of connective tissue continuous with the peritoneum.

Smooth mucosa along the inside of the lesser curvature forms a passageway - the gastric canal that fast-tracks liquids entering the stomach, to the pylorus.[10]

Glands

[edit]

The mucosa lining the stomach is lined with gastric pits, which receive gastric juice, secreted by between 2 and 7 gastric glands.[citation needed] Gastric juice is an acidic fluid containing hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes.[24] The glands contains a number of cells, with the function of the glands changing depending on their position within the stomach.[citation needed]

Within the body and fundus of the stomach lie the fundic glands. In general, these glands are lined by column-shaped cells that secrete a protective layer of mucus and bicarbonate. Additional cells present include parietal cells that secrete hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor, chief cells that secrete pepsinogen (this is a precursor to pepsin- the highly acidic environment converts the pepsinogen to pepsin), and neuroendocrine cells that secrete serotonin.[25][citation needed]

Glands differ where the stomach meets the esophagus and near the pylorus.[26] Near the gastroesophageal junction lie cardiac glands, which primarily secrete mucus.[25] They are fewer in number than the other gastric glands and are more shallowly positioned in the mucosa. There are two kinds - either simple tubular glands with short ducts or compound racemose resembling the duodenal Brunner's glands.[citation needed] Near the pylorus lie pyloric glands located in the antrum of the pylorus. They secrete mucus, as well as gastrin produced by their G cells.[27][citation needed]

Gene and protein expression

[edit]About 20,000 protein-coding genes are expressed in human cells and nearly 70% of these genes are expressed in the normal stomach.[28][29] Just over 150 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the stomach compared to other organs, with only some 20 genes being highly specific. The corresponding specific proteins expressed in stomach are mainly involved in creating a suitable environment for handling the digestion of food for uptake of nutrients. Highly stomach-specific proteins include gastrokine-1 expressed in the mucosa; pepsinogen and gastric lipase, expressed in gastric chief cells; and a gastric ATPase and gastric intrinsic factor, expressed in parietal cells.[30]

Development

[edit]In the early part of the development of the human embryo, the ventral part of the embryo abuts the yolk sac. During the third week of development, as the embryo grows, it begins to surround parts of the yolk sac. The enveloped portions form the basis for the adult gastrointestinal tract.[31] The sac is surrounded by a network of vitelline arteries and veins. Over time, these arteries consolidate into the three main arteries that supply the developing gastrointestinal tract: the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery. The areas supplied by these arteries are used to define the foregut, midgut, and hindgut.[31] The surrounded sac becomes the primitive gut. Sections of this gut begin to differentiate into the organs of the gastrointestinal tract, and the esophagus, and stomach form from the foregut.[31]

As the stomach rotates during early development, the dorsal and ventral mesentery rotate with it; this rotation produces a space anterior to the expanding stomach called the greater sac, and a space posterior to the stomach called the lesser sac. After this rotation the dorsal mesentery thins and forms the greater omentum, which is attached to the greater curvature of the stomach. The ventral mesentery forms the lesser omentum, and is attached to the developing liver. In the adult, these connective structures of omentum and mesentery form the peritoneum, and act as an insulating and protective layer while also supplying organs with blood and lymph vessels as well as nerves.[32] Arterial supply to all these structures is from the celiac trunk, and venous drainage is by the portal venous system. Lymph from these organs is drained to the prevertebral celiac nodes at the origin of the celiac artery from the aorta.

Function

[edit]Digestion

[edit]In the human digestive system, a bolus (a small rounded mass of chewed up food) enters the stomach through the esophagus via the lower esophageal sphincter. The stomach releases proteases (protein-digesting enzymes such as pepsin), and hydrochloric acid, which kills or inhibits bacteria and provides the acidic pH of 2 for the proteases to work. Food is churned by the stomach through peristaltic muscular contractions of the wall – reducing the volume of the bolus, before looping around the fundus[33] and the body of stomach as the boluses are converted into chyme (partially digested food). Chyme slowly passes through the pyloric sphincter and into the duodenum of the small intestine, where the extraction of nutrients begins.

Gastric juice in the stomach contains pepsinogen and gastric acid, (hydrochloric acid) which activates this inactive form of enzyme into the active form, pepsin. Pepsin breaks down proteins into polypeptides.

Mechanical digestion

[edit]Within a few moments after food enters the stomach, mixing waves begin to occur at intervals of approximately 20 seconds. A mixing wave is a unique type of peristalsis that mixes and softens the food with gastric juices to create chyme. The initial mixing waves are relatively gentle, but these are followed by more intense waves, starting at the body of the stomach and increasing in force as they reach the pylorus.

The pylorus, which holds around 30 mL of chyme, acts as a filter, permitting only liquids and small food particles to pass through the mostly, but not fully, closed pyloric sphincter. In a process called gastric emptying, rhythmic mixing waves force about 3 mL of chyme at a time through the pyloric sphincter and into the duodenum. Release of a greater amount of chyme at one time would overwhelm the capacity of the small intestine to handle it. The rest of the chyme is pushed back into the body of the stomach, where it continues mixing. This process is repeated when the next mixing waves force more chyme into the duodenum.

Gastric emptying is regulated by both the stomach and the duodenum. The presence of chyme in the duodenum activates receptors that inhibit gastric secretion. This prevents additional chyme from being released by the stomach before the duodenum is ready to process it.[34]

Chemical digestion

[edit]The fundus stores both undigested food and gases that are released during the process of chemical digestion. Food may sit in the fundus of the stomach for a while before being mixed with the chyme. While the food is in the fundus, the digestive activities of salivary amylase continue until the food begins mixing with the acidic chyme. Ultimately, mixing waves incorporate this food with the chyme, the acidity of which inactivates salivary amylase and activates lingual lipase. Lingual lipase then begins breaking down triglycerides into free fatty acids, and mono- and diglycerides.

The breakdown of protein begins in the stomach through the actions of hydrochloric acid, and the enzyme pepsin.

The stomach can also produce gastric lipase, which can help digesting fat.

The contents of the stomach are completely emptied into the duodenum within two to four hours after the meal is eaten. Different types of food take different amounts of time to process. Foods heavy in carbohydrates empty fastest, followed by high-protein foods. Meals with a high triglyceride content remain in the stomach the longest. Since enzymes in the small intestine digest fats slowly, food can stay in the stomach for 6 hours or longer when the duodenum is processing fatty chyme. However, this is still a fraction of the 24 to 72 hours that full digestion typically takes from start to finish.[34]

Absorption

[edit]Although the absorption in the human digestive system is mainly a function of the small intestine, some absorption of certain small molecules nevertheless does occur in the stomach through its lining. This includes:

- Water, if the body is dehydrated

- Medication, such as aspirin

- Amino acids[35]

- 10–20% of ingested ethanol (e.g. from alcoholic beverages)[36]

- Caffeine[37]

- To a small extent water-soluble vitamins (most are absorbed in the small intestine)[38]

The parietal cells of the human stomach are responsible for producing intrinsic factor, which is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12. B12 is used in cellular metabolism and is necessary for the production of red blood cells, and the functioning of the nervous system.

Control of secretion and motility

[edit]

Chyme from the stomach is slowly released into the duodenum through coordinated peristalsis and opening of the pyloric sphincter. The movement and the flow of chemicals into the stomach are controlled by both the autonomic nervous system and by the various digestive hormones of the digestive system:

| Gastrin | The hormone gastrin causes an increase in the secretion of HCl from the parietal cells and pepsinogen from chief cells in the stomach. It also causes increased motility in the stomach. Gastrin is released by G cells in the stomach in response to distension of the antrum and digestive products (especially large quantities of incompletely digested proteins). It is inhibited by a pH normally less than 4(high acid), as well as the hormone somatostatin. |

| Cholecystokinin | Cholecystokinin (CCK) has most effect on the gall bladder, causing gall bladder contractions, but it also decreases gastric emptying and increases release of pancreatic juice, which is alkaline and neutralizes the chyme. CCK is synthesized by I-cells in the mucosal epithelium of the small intestine. |

| Secretin | In a different and rare manner, secretin, which has the most effects on the pancreas, also diminishes acid secretion in the stomach. Secretin is synthesized by S-cells, which are located in the duodenal mucosa as well as in the jejunal mucosa in smaller numbers. |

| Gastric inhibitory polypeptide | Gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) decreases both gastric acid release and motility. GIP is synthesized by K-cells, which are located in the duodenal and jejunal mucosa. |

| Enteroglucagon | Enteroglucagon decreases both gastric acid and motility. |

Other than gastrin, these hormones all act to turn off the stomach action. This is in response to food products in the liver and gall bladder, which have not yet been absorbed. The stomach needs to push food into the small intestine only when the intestine is not busy. While the intestine is full and still digesting food, the stomach acts as storage for food.

Other

[edit]- Effects of EGF

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) results in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and survival.[39] EGF is a low-molecular-weight polypeptide first purified from the mouse submandibular gland, but since then found in many human tissues including the submandibular gland, and the parotid gland. Salivary EGF, which also seems to be regulated by dietary inorganic iodine, also plays an important physiological role in the maintenance of oro-esophageal and gastric tissue integrity. The biological effects of salivary EGF include healing of oral and gastroesophageal ulcers, inhibition of gastric acid secretion, stimulation of DNA synthesis, and mucosal protection from intraluminal injurious factors such as gastric acid, bile acids, pepsin, and trypsin and from physical, chemical, and bacterial agents.[40]

- Stomach as nutrition sensor

The human stomach has receptors responsive to sodium glutamate[41] and this information is passed to the lateral hypothalamus and limbic system in the brain as a palatability signal through the vagus nerve.[42] The stomach can also sense, independently of tongue and oral taste receptors, glucose,[43] carbohydrates,[44] proteins,[44] and fats.[45] This allows the brain to link nutritional value of foods to their tastes.[43]

- Thyrogastric syndrome

This syndrome defines the association between thyroid disease and chronic gastritis, which was first described in the 1960s.[46] This term was coined also to indicate the presence of thyroid autoantibodies or autoimmune thyroid disease in patients with pernicious anemia, a late clinical stage of atrophic gastritis.[47] In 1993, a more complete investigation on the stomach and thyroid was published,[48] reporting that the thyroid is, embryogenetically and phylogenetically, derived from a primitive stomach, and that the thyroid cells, such as primitive gastroenteric cells, migrated and specialized in uptake of iodide and in storage and elaboration of iodine compounds during vertebrate evolution. In fact, the stomach and thyroid share iodine-concentrating ability and many morphological and functional similarities, such as cell polarity and apical microvilli, similar organ-specific antigens and associated autoimmune diseases, secretion of glycoproteins (thyroglobulin and mucin) and peptide hormones, the digesting and readsorbing ability, and lastly, similar ability to form iodotyrosines by peroxidase activity, where iodide acts as an electron donor in the presence of H2O2. In the following years, many researchers published reviews about this syndrome.[49]

Clinical significance

[edit]

Diseases

[edit]A series of radiographs can be used to examine the stomach for various disorders. This will often include the use of a barium swallow. Another method of examination of the stomach, is the use of an endoscope. A gastric emptying study is considered the gold standard to assess the gastric emptying rate.[50]

A large number of studies have indicated that most cases of peptic ulcers, and gastritis, in humans are caused by Helicobacter pylori infection, and an association has been seen with the development of stomach cancer.[51]

A stomach rumble is actually noise from the intestines.

Surgery

[edit]In humans, many bariatric surgery procedures involve the stomach, in order to lose weight. A gastric band may be placed around the cardia area, which can adjust to limit intake. The anatomy of the stomach may be modified, or the stomach may be bypassed entirely.

Surgical removal of the stomach is called a gastrectomy, and removal of the cardia area is a called a cardiectomy. "Cardiectomy" is a term that is also used to describe the removal of the heart.[52][53][54] A gastrectomy may be carried out because of gastric cancer or severe perforation of the stomach wall.

Fundoplication is stomach surgery in which the fundus is wrapped around the lower esophagus and stitched into place. It is used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).[55]

Etymology

[edit]The word stomach is derived from Greek stomachos (στόμαχος), ultimately from stoma (στόμα) 'mouth'.[56] Gastro- and gastric (meaning 'related to the stomach') are both derived from Greek gaster (γαστήρ) 'belly'.[57][58][59]

Other animals

[edit]Although the precise shape and size of the stomach varies widely among different vertebrates, the relative positions of the esophageal and duodenal openings remain relatively constant. As a result, the organ always curves somewhat to the left before curving back to meet the pyloric sphincter. However, lampreys, hagfishes, chimaeras, lungfishes, and some teleost fish have no stomach at all, with the esophagus opening directly into the intestine. These animals all consume diets that require little storage of food, no predigestion with gastric juices, or both.[60]

|

|

The gastric lining is usually divided into two regions, an anterior portion lined by fundic glands and a posterior portion lined with pyloric glands. Cardiac glands are unique to mammals, and even then are absent in a number of species. The distributions of these glands vary between species, and do not always correspond with the same regions as in humans. Furthermore, in many non-human mammals, a portion of the stomach anterior to the cardiac glands is lined with epithelium essentially identical to that of the esophagus. Ruminants, in particular, have a complex four-chambered stomach. The first three chambers (rumen, reticulum, and omasum) are all lined with esophageal mucosa,[60] while the final chamber functions like a monogastric stomach, which is called the abomasum.

In birds and crocodilians, the stomach is divided into two regions. Anteriorly is a narrow tubular region, the proventriculus, lined by fundic glands, and connecting the true stomach to the crop. Beyond lies the powerful muscular gizzard, lined by pyloric glands, and, in some species, containing stones that the animal swallows to help grind up food.[60]

In insects, there is also a crop. The insect stomach is called the midgut.

Information about the stomach in echinoderms or molluscs can be found under the respective articles.

Additional images

[edit]-

Image showing the celiac artery and its branches

-

High-quality image of the stomach

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- ^ The Stomach at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- ^ "Definition of GASTRIC". www.merriam-webster.com. 12 May 2025. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Chaurasia, B.D. (2013). "19". Human Anatomy. Vol. 2 (6th ed.). 4819/XI, Prahlad Street, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110002, India: CBS Publishers and Distributors. pp. 250–252. ISBN 978-81-239-2331-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Sherwood, Lauralee (1997). Human physiology: from cells to systems. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-314-09245-8. OCLC 35270048.

- ^ Wenzel V, Idris AH, Banner MJ, Kubilis PS, Band R, Williams JL, et al. (1998). "Respiratory system compliance decreases after cardiopulmonary resuscitation and stomach inflation: impact of large and small tidal volumes on calculated peak airway pressure". Resuscitation. 38 (2): 113–8. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(98)00095-1. PMID 9863573.

- ^ Curtis, Helena & N. Sue Barnes (1994). Invitation to Biology (5 ed.). Worth.

- ^ Morris D. Kerstein, Barry Goldberg, Barry Panter, M. David Tilson, Howard Spiro, Gastric Infarction, Gastroenterology, Volume 67, Issue 6, 1974, Pages 1238–1239, ISSN 0016-5085, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(19)32710-6.

- ^ Tortora, Gerard J.; Derrickson, Bryan H. (2009). Principles of anatomy and physiology (12., internat. student version ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 937–942. ISBN 978-0-470-23347-4.

- ^ a b c d e Standring, Susan, Gray's Anatomy (42nd ed.), Elsevier, pp. 1160–1163

- ^ a b Brunicardi, F. Charles; Andersen, Dana K.; et al., eds. (2010). Schwartz's principles of surgery (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 978-0-07-154770-3.

- ^ a b c "Anatomy of the Stomach | SEER Training". training.seer.cancer.gov. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ [1] Habershon, S. H. "Diseases of the Stomach: A Manual for Practitioners and Students,"Chicago Medical Book Company, 1909, page 11.

- ^ [2] Weber, John and Shearer, Edwin Morrill "Shearer's manual of human dissection, Eighth Edition," McGraw Hill, 1999, page 157. ISBN 0-07-134624-4.

- ^ [3] Transactions of the Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland, Volume 14, 1896, "Birmingham, A(mbrose), "Topographical anatomy of the spleen, pancreas, duodenum, kidneys, &c.", pages 363-385. Retrieved 29 February 2011.

- ^ [4] The Lancet, Volume 1, Part 1, 22 February 1902. page 524, "Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland." Retrieved 28 February 2012

- ^ [5] The Dublin journal of medical science, Volume 114, page 353."Reviews and bibliographical notes." Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ Anne M. R. Agur; Moore, Keith L. (2007). Essential Clinical Anatomy (Point (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins)). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-6274-8. OCLC 172964542.; p. 150

- ^ "University of Rochester medical center". 2020. Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2021-12-19.

- ^ "Stomach histology". Kenhub. Retrieved 2021-01-09.

- ^ Welcome, Menizibeya Osain (2018). Gastrointestinal physiology: development, principles and mechanisms of regulation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 628. ISBN 978-3-319-91056-7. OCLC 1042217248.

- ^ "22.5C: Muscularis". Medicine LibreTexts. 2018-07-22. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ "SIU SOM Histology GI". www.siumed.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-01-11. Retrieved 2021-01-09.

- ^ "How does the Stomach Work?". National Institute of Health: National Library of Medicine. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). 21 August 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ a b Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 777. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ Gallego-Huidobro, J; Pastor, L M (April 1996). "Histology of the mucosa of the oesophagogastric junction and the stomach in adult Rana perezi". Journal of Anatomy. 188 (Pt 2): 439–444. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1167580. PMID 8621343.

- ^ Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 762. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ "The human proteome in stomach - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ^ Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220) 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ Gremel, Gabriela; Wanders, Alkwin; Cedernaes, Jonathan; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn; Edlund, Karolina; Sjöstedt, Evelina; Uhlén, Mathias; Pontén, Fredrik (2015-01-01). "The human gastrointestinal tract-specific transcriptome and proteome as defined by RNA sequencing and antibody-based profiling". Journal of Gastroenterology. 50 (1): 46–57. doi:10.1007/s00535-014-0958-7. ISSN 0944-1174. PMID 24789573. S2CID 21302849.

- ^ a b c Gary C. Schoenwolf (2009). "Development of the Gastrointestinal Tract". Larsen's human embryology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06811-9.

- ^ Sadler, T.W, (2011) Langman's Medical Embryology (12th edition), LWW, Baltimore, MD

- ^ Richard M. Gore; Marc S. Levine. (2007). Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology. Philadelphia, PA.: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2332-6.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (September 13, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 23.4 The Stomach. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (September 13, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 23.4 The Stomach. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

- ^ Krehbiel, C.R.; Matthews, J.C. "Absorption of Amino acids and Peptides" (PDF). In D'Mello, J.P.F. (ed.). Amino Acids in Animal Nutrition (2nd ed.). pp. 41–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2015-04-25.

- ^ "Alcohol and the Human Body". Intoximeters, Inc. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Debry, Gérard (1994). Coffee and Health (PDF (eBook)). Montrouge: John Libbey Eurotext. p. 129. ISBN 978-2-7420-0037-1. Retrieved 2015-04-26.

- ^ McGuire, Michelle; Beerman, Kathy (2012-01-01). Nutritional Sciences: From Fundamentals to Food (3 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 419. ISBN 978-1-133-70738-7.

- ^ Herbst RS (2004). "Review of epidermal growth factor receptor biology". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 59 (2 Suppl): 21–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.11.041. PMID 15142631.

- ^ Venturi S.; Venturi M. (2009). "Iodine in evolution of salivary glands and in oral health". Nutrition and Health. 20 (2): 119–134. doi:10.1177/026010600902000204. PMID 19835108. S2CID 25710052.

- ^ Uematsu, A; Tsurugizawa, T; Kondoh, T; Torii, K. (2009). "Conditioned flavor preference learning by intragastric administration of L-glutamate in rats". Neurosci. Lett. 451 (3): 190–3. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.12.054. PMID 19146916. S2CID 21764940.

- ^ Uematsu, A; Tsurugizawa, T; Uneyama, H; Torii, K. (2010). "Brain-gut communication via vagus nerve modulates conditioned flavor preference". Eur J Neurosci. 31 (6): 1136–43. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07136.x. PMID 20377626. S2CID 23319470.

- ^ a b De Araujo, Ivan E.; Oliveira-Maia, Albino J.; Sotnikova, Tatyana D.; Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Caron, Marc G.; Nicolelis, Miguel A.L.; Simon, Sidney A. (2008). "Food Reward in the Absence of Taste Receptor Signaling". Neuron. 57 (6): 930–41. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.032. PMID 18367093. S2CID 47453450.

- ^ a b Perez, C.; Ackroff, K.; Sclafani, A. (1996). "Carbohydrate- and protein conditioned flavor preferences: effects of nutrient preloads". Physiol. Behav. 59 (3): 467–474. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(95)02085-3. PMID 8700948. S2CID 23422504.

- ^ Ackroff, K.; Lucas, F.; Sclafani, A. (2005). "Flavor preference conditioning as a function of fat source". Physiol. Behav. 85 (4): 448–460. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.05.006. PMID 15990126. S2CID 7875868.

- ^ Doniach, D.; Roitt, I.M.; Taylor, K.B. (1965). "Autoimmunity in pernicious anemia and thyroiditis: a family study". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 124 (2): 605–25. Bibcode:1965NYASA.124..605D. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb18990.x. PMID 5320499. S2CID 39456072.

- ^ Cruchaud, A.; Juditz, E. (1968). "An analysis of gastric parietal cell antibodies and thyroid cell antibodies in patients with pernicious anaemia and thyroid disorders". Clin Exp Immunol. 3 (8): 771–81. PMC 1578967. PMID 4180858.

- ^ Venturi, S.; Venturi, A.; Cimini, D., Arduini, C; Venturi, M; Guidi, A. (1993). "A new hypothesis: iodine and gastric cancer". Eur J Cancer Prev. 2 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1097/00008469-199301000-00004. PMID 8428171.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lahner, E.; Conti, L.; Cicone, F. ; Capriello, S; Cazzato, M; Centanni, M; Annibale, B; Virili, C. (2019). "Thyro-entero-gastric autoimmunity: Pathophysiology and implications for patient management. A review". Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 33 (6) 101373. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2019.101373. PMID 31864909. S2CID 209446096.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Masaoka, Tatsuhiro; Tack, Jan (30 September 2009). "Gastroparesis: Current Concepts and Management". Gut and Liver. 3 (3): 166–173. doi:10.5009/gnl.2009.3.3.166. PMC 2852706. PMID 20431741.

- ^ Brown, LM (2000). "Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission". Epidemiologic Reviews. 22 (2): 283–97. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018040. PMID 11218379.

- ^ cardiectomy at dictionary.reference.com

- ^ Barlow, O. W. (1929). "The survival of the circulation in the frog web after cardiectomy". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 35 (1): 17–24. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ Meltzer, S. J. (1913). "The effect of strychnin in cardiectomized frogs with destroyed lymph hearts; a demonstration". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 10 (2): 23–24. doi:10.3181/00379727-10-16. S2CID 76506379.

- ^ Minjarez, Renee C.; Jobe, Blair A. (2006). "Surgical therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease". GI Motility Online. doi:10.1038/gimo56 (inactive 12 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Simpson, J. A. (1989). The Oxford English dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Stomach. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8.

- ^ gasth/r. The New Testament Greek Lexicon

- ^ gaster. dictionary.reference.com

- ^ Simpson, J. A. (1989). The Oxford English dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Gastro, Gastric. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8.

- ^ a b c Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 345–349. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- ^ William O. Reece (2005). Functional Anatomy and Physiology of Domestic Animals. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-7817-4333-4.

- ^ Finegan, Esther J. & Stevens, C. Edward. "Digestive System of Vertebrates". Archived from the original on 2008-12-01.

- ^ Khalil, Muhammad. "The anatomy of the digestive system". onemedicine.tuskegee.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-11-30.

- ^ a b c d Wilke, W. L.; Fails, A. D.; Frandson, R. D. (2009). Anatomy and physiology of farm animals. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-8138-1394-3.

External links

[edit]- Stomach at the Human Protein Atlas

- Digestion of proteins in the stomach or tiyan (archived 10 March 2007)

- Site with details of how ruminants process food (archived 27 October 2009)

- Control of Gastric Emptying (Archived 2019-11-12 at the Wayback Machine)

Stomach

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Gross anatomy

The stomach is a J-shaped, hollow, muscular organ situated in the upper abdomen, primarily on the left side of the midline, extending from the cardia at its junction with the esophagus to the pylorus connecting to the duodenum. It serves as a reservoir for ingested food and facilitates initial mechanical digestion through its distensible walls. The organ's overall dimensions in adults average approximately 25 cm in length and 10 to 12 cm in width, though these vary with body size and nutritional status.[2][6][7] The stomach is anatomically divided into five principal regions based on their positions and functions: the cardia, fundus, body, antrum, and pylorus. The cardia, the most proximal region, surrounds the esophageal opening and is a short conical area about 3 cm in diameter, positioned immediately below the diaphragm. Adjacent and superior to it is the fundus, a dome-shaped expansion that projects upward and to the left, often reaching the level of the fifth intercostal space, and comprising roughly 10-15% of the stomach's volume. The body, or corpus, forms the largest central portion, occupying about 50-60% of the total length, with a relatively uniform cylindrical shape that tapers distally. The antrum, distal to the body, is a funnel-shaped expansion of the pyloric region, measuring around 7-10 cm in length and serving as a mixing chamber; it transitions into the narrower pylorus, a 2-3 cm tubular segment ending at the pyloric sphincter. These regions vary in relative size, with the body being the most expansive and the pylorus the most constricted.[2][6][8][9] Surface features of the stomach include the greater and lesser curvatures, which define its convex and concave borders, respectively. The greater curvature, the longer outer convex margin (about 40 cm), arches from the cardia along the left inferior aspect to the pylorus, while the shorter lesser curvature (about 30 cm) forms the concave right medial border. Internally, the mucosa features prominent longitudinal folds known as gastric rugae, which are most evident in the empty state and allow the organ to expand; these folds are deepest in the body and fundus, diminishing toward the pylorus. The stomach's wall thickness varies regionally, averaging 2-3 mm in the body and fundus but increasing to 5-7 mm in the antrum and pylorus due to thicker muscle layers.[2][10][8][6] In its empty state, the stomach has a contracted capacity of about 50 ml, roughly the size of a fist, but it can distend to a typical resting volume of 1-1.5 liters and up to 4 liters when fully expanded during a meal, accommodating large boluses through relaxation of its muscular walls. The stomach is positioned beneath the liver and adjacent to the spleen on its superior and left aspects, respectively.[8][11][2]Location and relations

The stomach is situated in the left upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity, primarily within the epigastric and left hypochondriac regions, extending from the vertebral levels of T11 to L1 below the diaphragm.[12][13][14][2] It occupies a central position in the superior abdomen, lying between the esophagus superiorly and the duodenum inferiorly, with its J-shaped configuration allowing it to span from the midline toward the left side.[12][13] As an intraperitoneal organ, the stomach is fully enveloped by the peritoneum, which provides it with significant mobility within the abdominal cavity due to its mesentery attachments.[2][14] The greater omentum, a double-layered peritoneal fold, hangs from the greater curvature of the stomach and extends inferiorly to attach to the transverse colon, acting as an apron-like structure.[12][13] Along the lesser curvature, the lesser omentum connects the stomach to the liver, forming the gastrohepatic ligament, while the gastrosplenic ligament links the greater curvature to the spleen, further anchoring the organ while permitting flexibility.[13][14] This peritoneal investment allows the stomach to shift position with changes in body posture or during digestion, without fixed adhesions to surrounding structures.[2][12] Anteriorly, the stomach relates to the diaphragm, the left lobe of the liver, and the anterior abdominal wall, with the greater omentum also contributing to this surface.[2][12][13] Posteriorly, it is in close contact with several structures within the bed of the stomach, including the pancreas, the left kidney and adrenal gland, the spleen, the transverse colon via the transverse mesocolon, and the left dome of the diaphragm.[2][14][12] These relations position the fundus and body of the stomach against the posterior abdominal wall, while the pylorus approaches the midline.[13]Blood and lymphatic supply

The arterial supply of the stomach originates from the celiac trunk, which branches into the left gastric artery, splenic artery, and common hepatic artery at the level of the T12 vertebra. The left gastric artery ascends along the lesser curvature, providing branches to both anterior and posterior gastric walls. The splenic artery, coursing along the superior border of the pancreas, gives rise to 3–5 short gastric arteries that supply the fundus and upper greater curvature, as well as the left gastroepiploic (gastroomental) artery that runs along the greater curvature within the greater omentum. Meanwhile, the common hepatic artery provides the right gastric artery, which descends along the lesser curvature to anastomose with the left gastric artery, and through its gastroduodenal branch, the right gastroepiploic artery, which supplies the pylorus and lower greater curvature. These vessels interconnect via extensive anastomoses along both curvatures, forming arterial arcades that ensure redundant blood flow and resilience against occlusion.[2] Venous drainage from the stomach mirrors the arterial pattern and ultimately contributes to the portal venous system. The left and right gastric veins drain directly into the portal vein, while the short gastric veins and left gastroepiploic vein empty into the splenic vein, which then joins the superior mesenteric vein to form the portal vein. The right gastroepiploic vein drains into the superior mesenteric vein, facilitating efficient return of nutrient-rich blood from the stomach to the liver. This parallel venous architecture supports the organ's role in processing absorbed substances before hepatic metabolism.[2] Lymphatic drainage follows pathways aligned with the vascular supply, directing fluid from the stomach mucosa and submucosa to regional lymph nodes before converging on the celiac lymph nodes. Primary drainage occurs via gastric nodes along the lesser curvature, gastroepiploic nodes along the greater curvature, and pyloric nodes near the pylorus, with additional contributions from pancreaticosplenic nodes adjacent to the spleen and subpyloric nodes inferior to the pylorus. The stomach is divided into four lymphatic zones: zone 1 (cardia and upper right two-thirds) drains to left gastric nodes; zone 2 (pylorus and lower right two-thirds) to suprapyloric nodes; zone 3 (fundus and upper left one-third) to pancreaticosplenic nodes; and zone 4 (lower left one-third) to infrapyloric nodes. These routes form a hierarchical system that empties into celiac and intestinal trunk nodes, ultimately reaching thoracic duct cisterna chyli. The rich lymphatic network aids in immune surveillance and fluid balance within the gastric wall.[2]Innervation

The stomach receives dual autonomic innervation from the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, supplemented by the intrinsic enteric nervous system and sensory afferents that coordinate its functions in digestion.[15] The parasympathetic supply primarily arises from the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), which originates in the dorsal motor nucleus and nucleus tractus solitarius in the medulla oblongata. The vagus nerve divides into anterior and posterior trunks as it enters the abdomen through the esophageal hiatus, providing efferent fibers that stimulate gastric secretion of acid, enzymes, and mucus, as well as smooth muscle motility for mixing and propulsion of contents. These trunks give rise to branches targeting specific regions: gastric branches to the cardia and fundus, crow's foot branches to the pylorus and antrum, and intermediate branches to the body and greater curvature, enabling regional control of peristalsis and glandular activity.[16][15][17] Sympathetic innervation to the stomach derives from the greater, lesser, and least splanchnic nerves (T5–T12), which synapse in the celiac and superior mesenteric ganglia before forming the celiac plexus around the celiac artery. These noradrenergic fibers primarily inhibit motility, promote vasoconstriction of gastric vessels to regulate blood flow during stress, and transmit visceral pain signals via referral to thoracic dermatomes (e.g., epigastric region). The plexus distributes along arterial branches to innervate the muscularis externa, mucosa, and submucosa, counterbalancing parasympathetic effects to maintain homeostasis.[16][15][18] The enteric nervous system, often called the "second brain," comprises an intrinsic network of approximately 100 million neurons embedded in the stomach wall, enabling local reflex control independent of central input. It includes the myenteric (Auerbach's) plexus, located between the longitudinal and circular muscle layers, which coordinates motility through excitatory cholinergic and inhibitory nitrergic neurons that drive peristaltic waves and accommodation. The submucosal (Meissner's) plexus, situated in the submucosa (though sparser in the stomach compared to the intestine), regulates glandular secretion, mucosal blood flow, and electrolyte transport via secretomotor neurons, integrating sensory inputs for adaptive responses to luminal contents. These plexuses form interconnected circuits that process local stimuli, such as distension or pH changes, to sustain gastric function.[19][20][21] Sensory innervation involves visceral afferents from both vagal (about 40%) and spinal (60%) pathways, with cell bodies in the nodose ganglion and thoracic dorsal root ganglia (T4–L2, peaking at T10–T11), respectively. Vagal afferents, forming intramuscular arrays and intraganglionic laminar endings, detect mechanical distension and chemical stimuli (e.g., low pH or nutrients) to initiate reflexes for satiety and secretion, projecting to the nucleus tractus solitarius. Spinal afferents, often peptidergic (expressing CGRP and TRPV1), sense noxious distension, inflammation, or ischemia, transmitting pain via the spinothalamic tract to the spinal cord and higher centers, often resulting in poorly localized epigastric discomfort. These pathways ensure protective feedback, with vagal fibers handling physiological sensations and spinal fibers mediating nociception.[22][16][23]Histology

The stomach wall consists of four principal layers: the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa. The innermost mucosa comprises a simple columnar epithelium, a lamina propria of loose connective tissue rich in blood vessels and lymphoid tissue, and a thin muscularis mucosae of smooth muscle that allows for localized movements of the mucosal surface.[2] The submucosa, composed of dense irregular connective tissue, contains larger blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves, contributing to the stomach's ability to expand via rugae folds.[24] The muscularis externa features three smooth muscle layers—an inner oblique layer unique to the stomach for enhanced mixing, a middle circular layer that thickens at the pylorus to form the pyloric sphincter, and an outer longitudinal layer—enabling peristalsis and churning.[2] The outermost serosa is a layer of visceral peritoneum covering most of the stomach, providing lubrication and attachment.[25] The mucosa exhibits distinct regional variations corresponding to the cardia, fundus/body, and pylorus. In the cardia, near the esophagus, the mucosa contains short cardiac glands lined primarily by mucus-secreting cells, forming a protective zone.[24] The fundus and body, the main secretory regions, feature deeper gastric pits leading to long, branched fundic glands that extend through the lamina propria to the muscularis mucosae, populated by a mix of cell types.[2] The pylorus, transitioning to the duodenum, has shallower pits and predominantly pyloric glands rich in mucus-secreting cells and G-cells, with a thickened muscularis externa.[25] Key cellular components include surface mucous cells that line the luminal surface and gastric pits, providing a continuous epithelial barrier; mucous neck cells located in the upper portions of glands; chief cells in the deeper gland bases, characterized by basophilic cytoplasm; parietal cells scattered throughout the glands, with eosinophilic features; and enteroendocrine cells dispersed at gland bases, including G-cells in the pylorus.[2] Gastric pits serve as openings for coiled or tubular glands that penetrate the mucosa, differing from the small intestine by lacking villi and instead relying on these invaginations for surface area.[24] Gene expression profiles, such as those involving transcription factors like SOX2 in stem cells, help delineate these specialized cell lineages within the gastric epithelium.[26]Molecular biology

The molecular biology of the stomach encompasses distinct gene and protein expression profiles that underpin the functional specialization of its epithelial cells. Proteomic analyses of human stomach mucosa have identified over 14,000 proteins expressed across various regions, with a significant emphasis on digestive enzymes such as pepsinogens and transporters like ion pumps essential for acid secretion and nutrient processing.[27] These expression patterns exhibit regional specificity, with the fundus and corpus predominantly featuring proteins involved in acid production, while the antrum expresses mucins and hormones for mucosal protection and motility regulation.[28] In parietal cells, primarily located in the fundus and body regions, the ATP4A and ATP4B genes encode the alpha and beta subunits of the H+/K+-ATPase proton pump, which is crucial for gastric acid secretion. These genes are highly expressed in differentiated parietal cells, serving as markers of their maturation and functional identity during epithelial differentiation.[29] Similarly, the GIF gene, encoding gastric intrinsic factor, shows elevated expression in these cells, facilitating vitamin B12 absorption and contributing to the differentiated state of parietal lineages.[30] Chief cells, also concentrated in the fundus and corpus, exhibit high expression of the PGA3, PGA4, and PGA5 genes, which code for pepsinogen A precursors that activate into pepsins for protein digestion. According to data from the Human Protein Atlas, these pepsinogen genes demonstrate some of the highest transcript levels in chief cells (e.g., PGA3 at over 86,000 nTPM), underscoring their role as key indicators of chief cell differentiation and secretory function.[31] In the antrum, the GAST gene is prominently expressed in enteroendocrine G cells, producing gastrin to stimulate acid secretion and gastric motility, with transcript levels exceeding 9,000 nTPM as per Human Protein Atlas profiling. Mucin proteins, such as MUC5AC and MUC6, show regional enrichment in antral mucous cells, forming a protective barrier; MUC5AC is secreted by surface epithelium throughout the stomach but peaks in antral regions, while MUC6 predominates in glandular mucins of the antrum.[27] These patterns highlight how molecular expression drives cell-type specific functions and regional adaptations in the gastric mucosa.[28]Development

Embryonic origins

The stomach originates from the three primary germ layers formed during gastrulation in the early embryonic period. The endoderm contributes to the epithelial lining of the stomach and its associated glands, providing the foundational mucosal surface for digestion. The mesoderm differentiates into the connective tissues, including the lamina propria, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa, which form the structural framework of the organ. Additionally, neural crest-derived ectoderm gives rise to the enteric nervous system, enabling neural coordination of gastrointestinal functions.[32][33] As a derivative of the foregut, the stomach begins to form during the fourth week of embryonic development from a fusiform dilation of the caudal portion of the primitive gut tube, which is a hollow cylinder composed of endodermal cells surrounded by splanchnic mesoderm. By the fifth week, this dilation elongates and starts to exhibit regional distinctions, marking the initial organogenesis of the stomach within the foregut segment that extends from the pharynx to the duodenum. Initially positioned in the midline of the embryo, the primitive stomach remains attached to the body wall via a dorsal mesentery, which provides vascular and supportive connections.[33][34][32] During this early phase, the stomach undergoes a 90-degree clockwise rotation around its longitudinal axis, shifting its position to the left side of the abdominal cavity and establishing the orientation of its curvatures, with the lesser curvature facing medially. This rotation, occurring primarily in the fourth week, also contributes to the formation of the lesser peritoneal sac and repositions the cranial (cardiac) end downward to the left and the caudal (pyloric) end upward to the right. Key to these developmental processes is signaling via Sonic hedgehog (SHH), a protein secreted by the endodermal epithelium starting around embryonic day 8.5 in mammals; SHH acts in a paracrine manner to drive epithelial-mesenchymal interactions, promoting proliferation of mesenchymal progenitors, expansion of the mesenchyme, and differentiation of smooth muscle layers essential for stomach wall integrity.[33][34][35]Morphogenesis

The morphogenesis of the stomach involves dynamic shaping processes that transform the primitive foregut into its characteristic adult form, originating from the endoderm layer during early embryonic development.[36] Between weeks 5 and 8 of gestation, the foregut undergoes elongation and differential dilation, particularly along its dorsal aspect, expanding into a fusiform (spindle-shaped) structure that establishes the greater curvature while the ventral side forms the lesser curvature.[36] This period also features a 90-degree clockwise rotation around the stomach's longitudinal axis, reorienting the organ so that its original left surface faces anteriorly and the right surface posteriorly, with the left vagus nerve positioning anteriorly and the right posteriorly.[37] These changes occur concurrently with the growth of the dorsal mesogastrium, which elongates to form the future greater omentum, and the ventral mesogastrium, which contributes to the lesser omentum.[36] Vascular development supports this morphogenesis, with the celiac artery emerging as the primary arterial supply to the foregut derivatives, including the stomach, around weeks 5 to 6 as branches from the abdominal aorta organize to perfuse the expanding organ.[38] The omental development integrates with this, as the greater omentum derives from the dorsal mesentery and facilitates vascular connections, while venous drainage establishes via the portal system during the same timeframe.[36] Glandular differentiation follows, with the gastric mucosa beginning to invaginate by week 8 to form primitive pits and glands.[33] By week 12, parietal cells (responsible for acid secretion) and chief cells (pepsinogen producers) onset in the fundic and body regions, marking the start of specialized cell lineages, though full maturation continues into later gestation.[39] Functional secretion of gastric juices becomes operational by birth, enabling the newborn stomach to process milk.[36] Positional shifts accompany these internal changes, with the stomach initially forming in a superior midline position within the coelomic cavity and gradually descending from a more thoracic level to its final abdominal location in the upper left quadrant by weeks 8 to 10, driven by overall embryonic elongation and diaphragm partitioning.[37] Fixation occurs via peritoneal ligaments, including the gastrosplenic and splenorenal ligaments from the greater omentum and the hepatogastric ligament from the lesser omentum, stabilizing the organ relative to adjacent structures like the spleen, liver, and diaphragm.[36]Congenital anomalies

Congenital anomalies of the stomach encompass a range of developmental abnormalities arising during embryogenesis, primarily affecting the organ's structure, position, or function. These conditions deviate from normal gastric morphogenesis, where the stomach forms from the foregut around weeks 4-7 of gestation, leading to potential obstructions, malpositions, or ectopic tissues. While most are rare, they can manifest in neonates with gastrointestinal symptoms, necessitating early diagnostic evaluation. The most common congenital anomaly is infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS), characterized by thickening of the pyloric muscle, resulting in gastric outlet obstruction. Its incidence is approximately 1.3 to 3 per 1,000 live births, with higher rates in males (male-to-female ratio of 4:1 to 5:1) and first-born infants. Etiology involves multifactorial genetic predisposition and environmental factors, such as early exposure to erythromycin or maternal smoking during pregnancy. Clinically, it presents in infants aged 2-8 weeks with progressive, projectile non-bilious vomiting, leading to dehydration and failure to thrive if untreated; diagnosis is confirmed via ultrasound showing pyloric muscle thickness exceeding 3-4 mm. Gastric duplication cysts represent another frequent anomaly, comprising 2-9% of all gastrointestinal duplications, with an overall incidence of about 1 in 4,500 live births. These spherical or tubular cysts arise from aberrant foregut budding and share a muscular wall with the stomach, potentially communicating with the lumen. They often remain asymptomatic but can cause vomiting, abdominal pain, or bleeding due to ectopic gastric mucosa within the cyst; prenatal ultrasound or postnatal imaging like MRI aids diagnosis. Heterotopia, particularly pancreatic rests (ectopic pancreatic tissue), occurs in the stomach in up to 25-30% of cases, though symptomatic forms are rare, with an autopsy prevalence of 0.6-13.7% across gastrointestinal sites. This congenital malformation results from aberrant migration of pancreatic primordia during weeks 4-6 of development, lacking connection to the native pancreas. It typically presents incidentally during endoscopy as submucosal nodules in the antrum, but may cause dyspepsia, bleeding, or obstruction; endoscopic biopsy confirms acinar and ductal elements. Rarer anomalies include congenital microgastria, a hypoplastic tubular stomach with reduced capacity, reported in fewer than 30 cases worldwide, often associated with esophageal atresia or limb defects. Gastric atresia, usually pyloric, has an incidence of 1 in 100,000 births and stems from failed recanalization or vascular insult in utero, presenting with immediate postnatal non-bilious vomiting and polyhydramnios antenatally; upper GI series delineates the obstruction. Situs inversus affects gastric position in mirror-image reversal as part of totalis (incidence 1 in 10,000), linked to ciliopathy genes disrupting left-right asymmetry, and may lead to midgut malrotation with volvulus risk, diagnosed via imaging. Genetic factors, such as FOXF1 mutations, contribute to some anomalies like annular pancreas or malrotation impacting gastric function, occurring in contexts like alveolar capillary dysplasia.Physiology

Motility

The motility of the stomach encompasses a series of coordinated mechanical actions that mix, grind, and propel ingested food toward the small intestine. These movements are generated by the smooth muscle layers within the muscularis externa and are synchronized by electrical slow waves originating from interstitial cells of Cajal in the pacemaker region along the greater curvature. Peristaltic contractions initiate in the body of the stomach and propagate toward the pylorus, facilitating the distal movement of gastric contents.[5] Mixing waves, arising from rhythmic segmentation-like contractions, promote thorough blending of the food bolus with gastric secretions throughout the corpus and antrum.[40] In the antrum, retropulsion occurs as forceful peristaltic waves drive chyme against the tonically closed pyloric sphincter, redirecting larger particles proximally for additional fragmentation and enhancing overall mixing efficiency.[41] Gastric motility proceeds through distinct phases to optimize processing. Receptive relaxation, vagally mediated via inhibitory neurons releasing nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide, relaxes the proximal stomach (fundus and upper body) to accommodate up to 1-2 liters of food with minimal pressure rise.[5] This phase transitions to storage, where the fundus maintains low basal tone to retain the bolus without active propulsion. Grinding then dominates in the distal stomach, characterized by high-amplitude contractions occurring at a frequency of approximately 3 per minute, which reduce solid particles through shear forces and trituration.[40] The unique arrangement of the stomach's three smooth muscle layers underpins these motility patterns. The innermost oblique layer generates torque-like churning actions critical for grinding and mixing in the body and antrum. The middle circular layer produces constrictions that narrow the lumen, enabling peristaltic propulsion and pyloric regulation to control chyme outflow. The outermost longitudinal layer shortens the stomach during waves, contributing to overall propulsion from the body to the antrum.[5] Following grinding, gastric emptying ensues, with the stomach typically clearing a mixed meal over 2-4 hours, though the half-emptying time varies by content type. Liquids empty more rapidly via pressure gradients, while solids exhibit a lag phase before exponential emptying, influenced heavily by particle size—only particles smaller than 1-2 mm pass the pylorus, necessitating prior size reduction.[40] Neural control of these processes is primarily exerted through the vagus nerve, integrating sensory feedback to modulate contraction strength and relaxation.[5] A commonly reported sensation of an unsettled or "jiggly" stomach often occurs after consuming a heavy breakfast early in the morning following overnight fasting. The stomach, relatively empty after prolonged fasting, undergoes rapid distension upon ingestion of a large volume of food and secretions. This distension activates stretch receptors in the gastric wall, eliciting vigorous churning and mixing contractions to blend the contents with digestive juices. The semi-liquid gastric contents then slosh mechanically within the distended stomach, particularly during body movements, producing the perceived jiggly or unsettled feeling. High-fat or excessively large meals can delay gastric emptying, prolonging the distension and associated contractions, thereby extending the duration of the sensation.[40][5]Secretion

The stomach secretes gastric juice, a complex fluid essential for digestion, consisting primarily of hydrochloric acid (HCl), pepsinogen, mucus, intrinsic factor, and bicarbonate.[42] This secretion occurs from specialized cells in the gastric glands located in the mucosa.[5] Hydrochloric acid, secreted by parietal cells, maintains the gastric lumen at a highly acidic pH of 1.5 to 3.5 and is produced via the H+/K+-ATPase proton pump on the apical membrane of these cells, which exchanges intracellular H+ for extracellular K+.[8][43] Pepsinogen, the inactive precursor to the protease pepsin, is released by chief cells and activated in the acidic environment.[44] Mucus and bicarbonate are produced by surface mucous cells, forming a protective gel layer. Intrinsic factor, also from parietal cells, binds vitamin B12 to facilitate its absorption later in the intestine. The stomach produces approximately 2 to 3 liters of gastric juice daily in adults, with a low basal secretion rate during fasting that increases to peaks under stimulation, such as from meals.[45] This output supports digestive processes while balancing acidity.30287-1/pdf) To prevent self-digestion by the acidic and enzymatic contents, the gastric mucosa relies on a pre-epithelial protective barrier formed by mucus and bicarbonate secreted by surface epithelial cells, which traps bicarbonate to neutralize acid at the mucosal surface.[46] This mucus-bicarbonate layer maintains a near-neutral pH gradient adjacent to the epithelium despite the luminal acidity.[47] Gastric secretion is regulated in part by the hormone gastrin, released from G cells in the antrum, which stimulates parietal cell acid production.[48]Digestion

The stomach initiates the chemical digestion of proteins through the activation of pepsin, the primary proteolytic enzyme in gastric juice. Hydrochloric acid secreted by parietal cells reduces the intragastric pH to approximately 1.5–2, converting inactive pepsinogen—produced by chief cells—into active pepsin.[42] At this optimal pH of around 2, pepsin catalyzes the hydrolysis of internal peptide bonds in proteins, preferentially cleaving those adjacent to aromatic amino acids such as phenylalanine and tyrosine, thereby denaturing proteins and breaking them into smaller polypeptides and oligopeptides.[49] This process marks the beginning of protein degradation, preparing them for further enzymatic action in the small intestine. In contrast, digestion of carbohydrates and lipids is limited in the stomach. Salivary amylase, which begins starch breakdown in the mouth, becomes inactivated upon exposure to the acidic gastric environment, halting carbohydrate hydrolysis until pancreatic amylase acts in the duodenum.[49] Similarly, lipid digestion proceeds minimally via gastric lipase, secreted by chief cells, which hydrolyzes a small portion of triglycerides into diglycerides and free fatty acids, primarily affecting short- and medium-chain fats; the majority of lipid breakdown occurs later in the small intestine.[49] Beyond nutrient breakdown, the stomach's acidic milieu provides a critical defense against pathogens. The low pH of gastric juice, typically below 3, kills or inhibits the growth of many ingested bacteria and microbes, serving as a first line of protection against foodborne infections by disrupting microbial cell membranes and metabolic processes.[50][51] Through these chemical processes, aided briefly by mechanical mixing, the stomach transforms the ingested bolus into chyme—a viscous, semi-liquid mixture of partially digested food particles suspended in gastric secretions.[49] This chyme is then released incrementally through the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum for continued digestion and absorption.[52]Absorption

The stomach plays a limited role in nutrient and substance absorption, functioning primarily as a reservoir and initial processing site rather than a major uptake organ, with the small intestine handling the bulk of absorption. The gastric epithelium, characterized by its tight junctions and mucus coating, serves as a selective barrier that permits only passive diffusion of certain small, lipophilic molecules while preventing broader nutrient permeation to maintain mucosal integrity against the acidic lumen.[5][53] Among the primary absorptions in the stomach is ethanol (alcohol), which undergoes passive diffusion across the mucosa into the portal bloodstream, accounting for approximately 20-30% of ingested alcohol before the remainder passes to the small intestine for faster uptake. This gastric absorption is enhanced on an empty stomach but slowed by food, which delays emptying and reduces exposure. Similarly, aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are rapidly absorbed via passive diffusion in the acidic gastric environment, where their non-ionized form predominates, facilitating quick systemic effects but risking local irritation. Minor passive diffusion of water and electrolytes also occurs, though it represents a negligible fraction of total body fluid balance compared to intestinal reabsorption. The stomach absorbs limited short-chain fatty acids from partial lipid breakdown by gastric lipase, but long-chain lipids require further processing downstream.[54][55][56] The stomach contributes indirectly to vitamin B12 absorption by secreting intrinsic factor from parietal cells, a glycoprotein that binds dietary B12 in the acidic lumen, protecting it from degradation and enabling ileal uptake via receptor-mediated endocytosis; deficiency in intrinsic factor, as in pernicious anemia, severely impairs B12 absorption. In contrast, there is no significant gastric absorption of carbohydrates or proteins, as these require enzymatic breakdown into absorbable monomers primarily in the small intestine. The emphasis on barrier function underscores the stomach's protective role, with bicarbonate-rich mucus preventing back-diffusion of protons and luminal contents while limiting nutrient entry.[57][49]Regulation

The regulation of stomach functions, including secretion, motility, and emptying, is primarily governed by neural and hormonal mechanisms that integrate sensory inputs from the central nervous system, local enteric reflexes, and enteroendocrine signaling.[5] Neural control operates through three main phases: the cephalic phase, initiated by the sight, smell, or thought of food via vagal efferents that stimulate gastric glands; the gastric phase, involving local reflexes triggered by stomach distension and chemical stimuli; and the intestinal phase, featuring enterogastric inhibition to prevent overload of the duodenum.[5] These neural pathways ensure coordinated responses, with the vagus nerve playing a central role in transmitting cephalic signals and modulating local reflexes through the enteric nervous system.[58] Hormonal regulation complements neural inputs, with key peptides released from enteroendocrine cells in the stomach and duodenum. Gastrin, secreted by G cells in the gastric antrum in response to protein breakdown products and distension, potently stimulates hydrochloric acid secretion from parietal cells and enhances gastric motility.[48] In contrast, somatostatin from D cells inhibits gastrin release and acid secretion, acting as a paracrine brake.[58] Ghrelin, produced by P cells in the gastric fundus, promotes hunger signaling and stimulates acid secretion and gastric emptying via vagal pathways.[59] Cholecystokinin (CCK), released by duodenal I cells in response to fats, inhibits gastric emptying by relaxing the proximal stomach and contracting the pylorus, thereby slowing nutrient delivery to the intestine.[59] Delayed gastric emptying, such as that induced by high-fat or large-volume meals through mechanisms like CCK, can prolong gastric distension and vigorous mixing contractions, potentially leading to prolonged sensations of an unsettled or jiggly stomach due to mechanical sloshing of semi-liquid gastric contents, particularly after a heavy breakfast following overnight fasting.[59] Gastric secretion occurs in overlapping phases that contribute variably to total acid output: the cephalic phase accounts for approximately 20-30%, driven by anticipatory vagal stimulation; the gastric phase contributes 60-70%, via direct luminal and distension stimuli; and the intestinal phase adds about 10%, primarily through modulatory hormones like CCK and secretin.[5] Feedback loops maintain homeostasis, with distension receptors in the gastric wall detecting food volume to trigger local reflexes and gastrin release, promoting further secretion and motility.[58] pH-sensing mechanisms in the antrum and duodenum activate somatostatin release when acidity rises, inhibiting further acid production to protect the mucosa.[5] These loops, integrated via neural and hormonal signals, prevent excessive secretion and coordinate digestion with downstream intestinal capacity.[60]Clinical aspects

Disorders

The stomach is susceptible to a range of disorders, broadly categorized into inflammatory, neoplastic, and functional conditions, each with distinct etiologies and clinical implications. Inflammatory disorders, such as gastritis and peptic ulcers, represent the most common pathologies affecting gastric mucosa integrity. Gastritis involves inflammation of the stomach lining and can be acute or chronic; chronic gastritis is frequently associated with Helicobacter pylori infection, which has a global prevalence of approximately 43% in adults based on recent meta-analyses.[61] H. pylori-related gastritis often leads to atrophic changes over time, increasing susceptibility to further complications. Peptic ulcer disease, encompassing both gastric and duodenal ulcers, is predominantly linked to H. pylori infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use; globally, its prevalence reached about 8 million cases in 2019, with a noted increase from prior decades.[62] Recent advancements include FDA-approved vonoprazan-based regimens in 2024 for H. pylori eradication, offering higher success rates in bismuth quadruple therapy.[63] These ulcers result from an imbalance between protective mucosal factors and aggressive elements like acid and pepsin, often manifesting as abdominal pain, bleeding, or perforation. Neoplastic disorders of the stomach primarily include gastric adenocarcinoma and lymphomas, posing significant global health burdens. Gastric adenocarcinoma, the predominant form of stomach cancer, accounted for 968,784 new cases worldwide in 2022 (GLOBOCAN estimates), with key risk factors including H. pylori infection, dietary habits high in salted or smoked foods, and smoking.[64] Recent advances include the 2024 approval of zolbetuximab for CLDN18.2-positive advanced cases, enhancing targeted treatment options.[65] This malignancy typically arises from chronic gastritis progressing through metaplasia, dysplasia, and invasive carcinoma, exhibiting geographic variations with higher incidence in East Asia and Latin America. Gastric lymphomas, particularly mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, constitute about 5% of all gastric neoplasms and are the most common extranodal lymphomas in the stomach; many are H. pylori-associated, where infection drives lymphoproliferation.[66] Functional disorders, such as dyspepsia and gastroparesis, involve impaired gastric function without structural abnormalities. Functional dyspepsia, characterized by epigastric pain or discomfort without evidence of organic disease, has a global prevalence of approximately 7% according to recent studies using Rome IV criteria, varying by region and diagnostic standards.[67] Gastroparesis refers to delayed gastric emptying due to motility dysfunction, often linked to diabetes mellitus; in diabetic patients, its prevalence is estimated at 9.3%, with higher rates in type 1 diabetes due to autonomic neuropathy affecting gastric nerves. The 2025 AGA guideline recommends erythromycin and metoclopramide for symptom management, with emerging therapies like relamorelin under investigation.[68] These conditions contribute to symptoms like nausea, bloating, and early satiety, impacting quality of life. Recent epidemiological shifts highlight rising cases of non-H. pylori gastritis attributed to NSAIDs, which induce reactive changes in the gastric mucosa independently of infection, with studies noting an increase in such NSAID-associated lesions amid widespread analgesic use.[69] Furthermore, post-2020 research has elucidated the gut microbiome's role in gastric cancer pathogenesis, where dysbiosis—beyond H. pylori—promotes inflammation, immune evasion, and oncogenesis through microbial metabolites and interactions with host cells.[70] For severe cases of these disorders, such as advanced ulcers or neoplasms, surgical interventions like partial gastrectomy may be considered to alleviate complications.Surgical procedures