Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chord notation

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2019) |

Musicians use various kinds of chord names and symbols in different contexts to represent musical chords. In most genres of popular music, including jazz, pop, and rock, a chord name and its corresponding symbol typically indicate one or more of the following:

- the root note (e.g. C♯)

- the chord quality (e.g. minor or lowercase m, or the symbols o or + for diminished and augmented chords, respectively; chord quality is usually omitted for major chords)

- whether the chord is a triad, seventh chord, or an extended chord (e.g. Δ7)

- any altered notes (e.g. sharp five, or ♯5)

- any added tones (e.g. add2)

- the bass note if it is not the root (e.g. a slash chord)

| Triad | Root | Quality | Example | Audio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major triad | Uppercase | C | ||

| Minor triad | Lowercase | c | ||

| Augmented triad | Uppercase | + | C+ | |

| Diminished triad | Lowercase | o | co | |

| Dominant seventh | Uppercase | 7 | C7 |

For instance, the name C augmented seventh, and the corresponding symbol Caug7, or C+7, are both composed of parts 1 (letter 'C'), 2 ('aug' or '+'), and 3 (digit '7'). These indicate a chord formed by the notes C–E–G♯–B♭. The three parts of the symbol (C, aug, and 7) refer to the root C, the augmented (fifth) interval from C to G♯, and the (minor) seventh interval from C to B♭.

Although they are used occasionally in classical music, typically in an educational setting for harmonic analysis, these names and symbols are "universally used in jazz and popular music",[1] in lead sheets, fake books, and chord charts, to specify the chords that make up the chord progression of a song or other piece of music. A typical sequence of a jazz or rock song in the key of C major might indicate a chord progression such as

- C – Am – Dm – G7.

This chord progression instructs the performer to play, in sequence, a C major triad, an A minor chord, a D minor chord, and a G dominant seventh chord. In a jazz context, players have the freedom to add sevenths, ninths, and higher extensions to the chord. In some pop, rock and folk genres, triads are generally performed unless specified in the chord chart.

Purpose

[edit]These chord symbols are used by musicians for a number of purposes. Chord-playing instrumentalists in the rhythm section, such as pianists, use these symbols to guide their improvised performance of chord voicings and fills. A rock or pop guitarist or keyboardist might literally play the chords as indicated (e.g., the C major chord would be played by playing the notes C, E and G at the same time). In jazz, particularly for music from the 1940s bebop era or later, players typically have latitude to add in the sixth, seventh, and/or ninth of the chord. Jazz chord voicings often omit the root (leaving it to the bass player) and fifth. As such, a jazz guitarist might voice the C major chord with the notes E, A and D—which are the third, sixth, and ninth of the chord. The bassist (electric bass or double bass) uses the chord symbols to help improvise a bass line that outlines the chords, often by emphasizing the root and other key scale tones (third, fifth, and in a jazz context, the seventh).

The lead instruments, such as a saxophonist or lead guitarist, use the chord chart to guide their improvised solos. The instrumentalist improvising a solo may use scales that work well with certain chords or chord progressions, according to the chord-scale system. For example, in rock and blues soloing, the pentatonic scale built on the root note is widely used to solo over straightforward chord progressions that use I, IV, and V chords (in the key of C major, these would be the chords C, F, and G7).

In a journal of the American Composers Forum the use of letters to indicate chords is defined as, "a reductive analytical system that views music via harmonic motion to and from a target chord or tonic".[2] In 2003 Benjamin, Horvit, and Nelson describe the use of letters to indicate chord root as, "popular music ([and/specifically] jazz) lead sheet symbols."[3] The use of letters, "is an analytical technique that may be employed along with, or instead of, more conventional methods of analysis such as Roman numeral analysis. The system employs letter names to indicate the roots of chords, accompanied by specific symbols to depict chord quality."[4]

Other notation systems for chords include:[5]

- Traditional staff notation.

- Roman numerals, commonly used in harmonic analysis.[6]

- figured bass, widely used in the Baroque era.

- numbered musical notation, a musical notation that use numbers characters instance of graphical symbols, widely used in China.

- Nashville Number System, a variant of modern chord symbols, that use Arabic numerals for scale degrees.

Chord quality

[edit]Chord qualities are related to the qualities of the component intervals that define the chord. The main chord qualities are:

- Major and minor

- Augmented, diminished, and half-diminished

- Dominant

Some of the symbols used for chord quality are similar to those used for interval quality:

- No symbol, or sometimes M or Maj for major

- m, or min for minor

- aug or Aug for augmented

- dim for diminished

In addition,

- Δ is used for major seventh,[a] instead of the standard M, or maj

- − is sometimes used for minor, instead of the standard m or min

- a lowercase root note is sometimes used for minor, e.g. c instead of Cm

- + is used for augmented (A is not used, but sometimes Aug is used, e.g. Aug6)

- o is for diminished (d is not used)

- ø is used for half-diminished

- dom may occasionally be used for dominant

Chord qualities are sometimes omitted. When specified, they appear immediately after the root note or, if the root is omitted, at the beginning of the chord name or symbol. For instance, in the symbol Cm7 (C minor seventh chord) C is the root and m is the chord quality. When the terms minor, major, augmented, diminished, or the corresponding symbols do not appear immediately after the root note, or at the beginning of the name or symbol, they should be considered interval qualities, rather than chord qualities. For instance, in CmM7 (minor major seventh chord), m is the chord quality and M refers to the ![]() interval.

interval.

Major, minor, augmented, and diminished chords

[edit]Three-note chords are called triads. There are four basic triads (major, minor, augmented, diminished). They are all tertian—which means defined by the root, a third, and a fifth. Since most other chords are made by adding one or more notes to these triads, the name and symbol of a chord is often built by just adding an interval number to the name and symbol of a triad. For instance, a C augmented seventh chord is a C augmented triad with an extra note defined by a minor seventh interval:

| C+ 7 | = | C+ | + | ♭ |

| augmented seventh chord |

augmented triad |

minor seventh |

In this case, the quality of the additional interval is omitted. Less often, the full name or symbol of the additional interval (minor, in the example) is provided. For instance, a C augmented major seventh chord is a C augmented triad with an extra note defined by a major seventh interval:

| C+Δ 7 | = | C+ | + | |

| augmented major seventh chord |

augmented triad |

major seventh |

In both cases, the quality of the chord is the same as the quality of the basic triad it contains. This is not true for all chord qualities: the chord qualities half-diminished and dominant refer not only to the quality of the basic triad but also the quality of the additional intervals.

Altered fifths

[edit]A more complex approach is sometimes used to name and denote augmented and diminished chords. An augmented triad can be viewed as a major triad in which the perfect fifth interval (spanning 7 semitones) has been substituted with an augmented fifth (8 semitones). A diminished triad can be viewed as a minor triad in which the perfect fifth has been substituted with a diminished fifth (6 semitones). In this case, the augmented triad can be named major triad sharp five, or major triad augmented fifth (M♯5, M+5, majaug5). Similarly, the diminished triad can be named minor triad flat five, or minor triad diminished fifth (m♭5, mo5, mindim5).

Again, the terminology and notation used for triads affects the terminology and notation used for larger chords, formed by four or more notes. For instance, the above-mentioned C augmented major seventh chord, is sometimes called C major seventh sharp five, or C major seventh augmented fifth. The corresponding symbol is CM7+5, CM7♯5, or Cmaj7aug5:

| CM7+5 | = | C | + | M3 | + | A5 | + | M7 |

| augmented chord |

chord root |

major interval |

augmented interval |

major interval |

- (In chord symbols, the symbol A, used for augmented intervals, is typically replaced by + or ♯)

In this case, the chord is viewed as a C major seventh chord (CM7) in which the third note is an augmented fifth from root (G♯), rather than a perfect fifth from root (G). All chord names and symbols including altered fifths, i.e., augmented (♯5, +5, aug5) or diminished (♭5, o5, dim5) fifths can be interpreted in a similar way.

Common types of chords

[edit]Triads

[edit]

As shown in the table below, there are four triads, each made up of the root, the third (either major [M3] or minor [m3]) above the root, and the fifth (perfect [P5], augmented [A5], or diminished [d5]) above the root. The table below shows the names, symbols, and definition for the four triads, using C as the root.

| Name | Semi- tones [citation needed] |

Symbols (on C) | Definitions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Altered fifth |

Component intervals | Notes (on C) | |||

| Third | Fifth | ||||||

| Major triad | 047 | C CM[b] CΔ[a] |

Cmaj[b] | M3 | P5 | C–E–G | |

| Minor triad | 037 | Cm C− |

Cmin | m3 | P5 | C–E♭–G | |

| Augmented triad (major triad sharp five) |

048 | C+ | Caug | CM♯5 CM+5 |

M3 | A5 | C–E–G♯ |

| Diminished triad (minor triad flat five) |

036 | Co | Cdim | Cm♭5 Cmo5 |

m3 | d5 | C–E♭–G♭ |

Seventh chords

[edit]

A seventh chord is a triad with a seventh. The seventh is either a major seventh [M7] above the root, a minor seventh [m7] above the root (flatted 7th), or a diminished seventh [d7] above the root (double flatted 7th). Note that the diminished seventh note is enharmonically equivalent to the major sixth above the root of the chord.

The table below shows the names, symbols, and definitions for the various kinds of seventh chords, using C as the root.

| Name | Semi- tones [citation needed] |

Symbols (on C) | Definitions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Altered fifth |

Component intervals | Notes (on C) | ||||

| Third | Fifth | Seventh | ||||||

| Dominant seventh | 047X | C7 CMm7 |

Cmaj♭7 Cmajm7 |

M3 | P5 | m7 | C–E–G–B♭ | |

| Major seventh | 047N | CM7 CMa7 Cmaj7 CΔ7 CΔ[a] |

Cmaj7 | M3 | P5 | M7 | C–E–G–B | |

| Minor-major seventh | 037N | CmM7 Cm♯7 C−M7 C−Δ7 C−Δ |

Cminmaj7 | m3 | P5 | M7 | C–E♭–G–B | |

| Minor seventh | 037X | Cm7 C–7 |

Cmin7 | m3 | P5 | m7 | C–E♭–G–B♭ | |

| Augmented-major seventh (major seventh sharp five) |

048N | C+M7 C+Δ |

Caugmaj7 | CM7♯5 CM7+5 CΔ♯5 CΔ+5 |

M3 | A5 | M7 | C–E–G♯–B |

| Augmented seventh (dominant seventh sharp five) |

048X | C+7 | Caug7 | C7♯5 C7+5 |

M3 | A5 | m7 | C–E–G♯–B♭ |

| Half-diminished seventh (minor seventh flat five) |

036X | Cø Cø7 |

Cmin7dim5 | Cm7♭5 Cm7o5 C−7♭5 C−7o5 |

m3 | d5 | m7 | C–E♭–G♭–B♭ |

| Diminished seventh | 0369 | Co7 | Cdim7 | m3 | d5 | d7 | C–E♭–G♭–B | |

| Dominant seventh flat five | 046X | C7♭5 | C7dim5 | M3 | d5 | m7 | C–E–G♭–B♭ | |

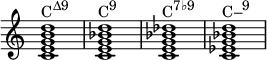

Extended chords

[edit]Extended chords add further notes to seventh chords. Of the seven notes in the major scale, a seventh chord uses only four (the root, third, fifth, and seventh). The other three notes (the second, fourth, and sixth) can be added in any combination; however, just as with the triads and seventh chords, notes are most commonly stacked – a seventh implies that there is a fifth and a third and a root. In practice, especially in jazz, certain notes can be omitted without changing the quality of the chord. In a jazz ensemble with a bass player, the chord-playing instrumentalists (guitar, organ, piano, etc.) can omit the root, as the bass player typically plays it.

Ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords are known as extended tertian chords. These notes are enharmonically equivalent to the second, fourth, and sixth, respectively, except they are more than an octave above the root. However, this does not mean that they must be played in the higher octave. Although changing the octave of certain notes in a chord (within reason) does change the way the chord sounds, it does not change the essential characteristics or tendency of it. Accordingly, using the ninth, eleventh, or thirteenth in chord notation implies that the chord is an extended tertian chord rather than an added chord.

The convention is that using an odd number (7, 9, 11, or 13) implies that all the other lower odd numbers are also included. Thus C13 implies that 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 are also there. Using an even number such as 6, implies that only that one extra note has been added to the base triad e.g. 1, 3, 5, 6. Remember that this is theory, so in practice they do not have to be played in that ascending order e.g. 5, 1, 6, 3. Also, to resolve the clash between the third and eleventh, one of them may be deleted or separated by an octave. Another way to resolve might be to convert the chord to minor by lowering the third, which generates a clash between the ♭3 and the 9.

Ninth chords

[edit]

Ninth chords are built by adding a ninth to a seventh chord, either a major ninth [M9] or a minor ninth [m9]. A ninth chord includes the seventh; without the seventh, the chord is not an extended chord but an added tone chord—in this case, an add 9. Ninths can be added to any chord but are most commonly seen with major, minor, and dominant seventh chords. The most commonly omitted note for a voicing is the perfect fifth.

The table below shows the names, symbols, and definitions for the various kinds of ninth chords, using C as the root.

| Name | Semi- tones [citation needed] |

Symbols (on C) | Quality of added 9th |

Notes (on C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | ||||

| Major ninth | 047N2 | CM9 CΔ9 |

Cmaj9 | M9 | C–E–G–B–D |

| Dominant ninth | 047X2 | C9 | M9 | C–E–G–B♭–D | |

| Dominant minor ninth | 047X1 | C7♭9 | m9 | C–E–G–B♭–D♭ | |

| Minor-major ninth | 037N2 | CmM9 C−M9 |

Cminmaj9 | M9 | C–E♭–G–B–D |

| Minor ninth | 037X2 | Cm9 C−9 |

Cmin9 | M9 | C–E♭–G–B♭–D |

| Augmented major ninth | 048N2 | C+M9 | Caugmaj9 | M9 | C–E–G♯–B–D |

| Augmented dominant ninth | 048X2 | C+9 C9♯5 |

Caug9 | M9 | C–E–G♯–B♭–D |

| Half-diminished ninth | 036X2 | Cø9 | M9 | C–E♭–G♭–B♭–D | |

| Half-diminished minor ninth | 036X1 | Cø♭9 | m9 | C–E♭–G♭–B♭–D♭ | |

| Diminished ninth | 03692 | Co9 | Cdim9 | M9 | C–E♭–G♭–B |

| Diminished minor ninth | 03691 | Co♭9 | Cdim♭9 | m9 | C–E♭–G♭–B |

Eleventh chords

[edit]

Eleventh chords are theoretically ninth chords with the 11th (or fourth) added. However, it is common to leave certain notes out. The major third is often omitted because of a strong dissonance with the 11th, making the third an avoid note.[citation needed] Omission of the third reduces an 11th chord to the corresponding 9sus4 chord (suspended 9th chord[7]). Similarly, omission of the third as well as fifth in C11 results in a major chord with alternate base B♭/C, which is characteristic in soul and gospel music. For instance:

- C11 without 3rd = C–(E)–G–B♭–D–F ➡ C–F–G–B♭–D = C9sus4

- C11 without 3rd and 5th = C–(E)–(G)–B♭–D–F ➡ C–F–B♭–D = B♭/C

If the ninth is omitted, the chord is no longer an extended chord but an added tone chord. Without the third, this added tone chord becomes a 7sus4 (suspended 7th chord). For instance:

- C11 without 9th = C7add11 = C–E–G–B♭–(D)–F

- C7add11 without 3rd = C–(E)–G–B♭–(D)–F ➡ C–F–G–B♭ = C7sus4

The table below shows the names, symbols, and definitions for the various kinds of eleventh chords, using C as the root.

| Name | semi- tones |

Symbols (on C) | Quality of added 11th |

Notes (on C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | ||||

| Eleventh | 047X25 | C11 | P11 | C–E–G–B♭–D–F | |

| Major eleventh | 047N25 | CM11 | Cmaj11 | P11 | C–E–G–B–D–F |

| Minor major eleventh | 037N25 | CmM11 C−M11 |

Cminmaj11 | P11 | C–E♭–G–B–D–F |

| Minor eleventh | 037X25 | Cm11 C−11 |

Cmin11 | P11 | C–E♭–G–B♭–D–F |

| Augmented major eleventh | 048N25 | C+M11 | Caugmaj11 | P11 | C–E–G♯–B–D–F |

| Augmented eleventh | 048X25 | C+11 C11♯5 |

Caug11 | P11 | C–E–G♯–B♭–D–F |

| Half-diminished eleventh | 036X25 | Cø11 | P11 | C–E♭–G♭–B♭–D–F | |

| Diminished eleventh | 036925 | Co11 | Cdim11 | P11 | C–E♭–G♭–B |

Alterations from the natural diatonic chords can be specified as C9♯11, A♭M9♯11 ... etc. Omission of the fifth in a raised 11th chord reduces its sound to a ♭5 chord.[8]

- C9♯11 = C–E–(G)–B♭–D–F♯ ➡ C–E–G♭–B♭–D = C9♭5.

Thirteenth chords

[edit]

Thirteenth chords are theoretically eleventh chords with the 13th (or sixth) added. In other words, theoretically they are formed by all the seven notes of a diatonic scale at once. Again, it is common to leave certain notes out. After the fifth, the most commonly omitted note is the 11th (fourth). The ninth (second) may also be omitted. A very common voicing on guitar for a 13th chord is just the root, third, seventh and 13th (or sixth). For example: C–E–(G)–B♭–(D)–(F)–A, or C–E–(G)–A–B♭–(D)–(F). On the piano, this is usually voiced C–B♭–E–A.

The table below shows the names, symbols, and definitions for some thirteenth chords, using C as the root.

| Name | semi- tones |

Symbols (on C) | Quality of added 13th |

Notes (on C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | ||||

| Major thirteenth | 047N259 | CM13 CΔ13 |

Cmaj13 | M13 | C–E–G–B–D–F–A |

| Thirteenth | 047X259 | C13 | M13 | C–E–G–B♭–D–F–A | |

| Minor major thirteenth | 037N259 | CmM13 C−M13 |

Cminmaj13 | M13 | C–E♭–G–B–D–F–A |

| Minor thirteenth | 037X259 | Cm13 C−13 |

Cmin13 | M13 | C–E♭–G–B♭–D–F–A |

| Augmented major thirteenth | 048N259 | C+M13 | Caugmaj13 | M13 | C–E–G♯–B–D–F–A |

| Augmented thirteenth | 048X259 | C+13 C13♯5 |

Caug13 | M13 | C–E–G♯–B♭–D–F–A |

| Half-diminished thirteenth | 036X259 | Cø13 | M13 | C–E♭–G♭–B♭–D–F–A | |

Alterations from the natural diatonic chords can be specified as C11♭13, Gm11♭9♭13 ... etc.

Added tone chords

[edit]

There are two ways to show that a chord is an added tone chord, and it is very common to see both methods on the same score. One way is to simply use the word 'add', for example, Cadd 9. The second way is to use 2 instead of 9, implying that it is not a seventh chord, for instance, C2. Note that this provides other ways of showing a ninth chord, for instance, C7add 9, C7add 2, or C7/9. Generally however, this is shown as simply C9, which implies a seventh in the chord. Added tone chord notation is useful with seventh chords to indicate partial extended chords, for example, C7add 13, which indicates that the 13th is added to the 7th, but without the 9th and 11th.

The use of 2, 4, and 6 rather than 9, 11, and 13 indicates that the chord does not include a seventh unless explicitly specified. However, this does not mean that these notes must be played within an octave of the root, nor the extended notes in seventh chords should be played outside of the octave, although it is commonly the case. 6 is particularly common in a minor sixth chord (also known as minor/major sixth chord, as the 6 refers to a major sixth interval).

It is possible to have added tone chords with more than one added note. The most commonly encountered of these are 6/9 chords, which are basic triads with the sixth and second notes of the scale added. These can be confusing because of the use of 9, yet the chord does not include the seventh. A good rule of thumb is that if any added note is less than 7, then no seventh is implied, even if there are some notes shown as greater than 7.

Suspended chords

[edit]

Suspended chords are notated with the symbols "sus4" or "sus2". When "sus" is alone, the suspended fourth chord is implied. This "sus" indication can be combined with any other notation. For example, the notation C9sus4 refers to a ninth chord with the third replaced by the fourth: C–F–G–B♭–D. However, the major third can also be added as a tension above the fourth to "colorize" the chord: C–F–G–B♭–D–E. A sus4 chord with the added major third (sometimes called a major 10th) can also be voiced quartally as C–F–B♭–E.

Power chords

[edit]Though power chords are not true chords per se, as the term "chord" is generally defined as three or more different pitch classes sounded simultaneously, and a power chord contains only two (the root, the fifth, and often a doubling of the root at the octave), power chords are still expressed using a version of chord notation. Most commonly, power chords (e.g., C–G–C) are expressed using a "5" (e.g., C5). Power chords are also referred to as fifth chords, indeterminate chords, or neutral chords[citation needed] (not to be confused with the quarter tone neutral chord, a stacking of two neutral thirds, e.g. C–E![]() –G) since they are inherently neither major nor minor; generally, a power chord refers to a specific doubled-root, three-note voicing of a fifth chord.

–G) since they are inherently neither major nor minor; generally, a power chord refers to a specific doubled-root, three-note voicing of a fifth chord.

To represent an extended neutral chord, e.g., a seventh (C–G–B♭), the chord is expressed as its corresponding extended chord notation with the addition of the words "no3rd," "no3" or the like. The aforementioned chord, for instance, could be indicated with C7no3.

Slash chords

[edit]

An inverted chord is a chord with a bass note that is a chord tone but not the root of the chord. Inverted chords are noted as slash chords with the note after the slash being the bass note. For instance, the notation C/E bass indicates a C major triad in first inversion i.e. a C major triad with an E in the bass. Likewise the notation C/G bass indicates that a C major chord with a G in the bass (second inversion).

See figured bass for alternate method of notating specific notes in the bass.

Upper structures are notated in a similar manner to inversions, except that the bass note is not necessarily a chord tone. For example:

- C/A♭ bass (A♭–C–E–G), which is equivalent to A♭M7♯5,

- C♯/E bass (E–G♯–C♯–E♯), and

- Am/D bass (D–A–C–E).

Chord notation in jazz usually gives a certain amount of freedom to the player for how the chord is voiced, also adding tensions (e.g., 9th) at the player's discretion. Therefore, upper structures are most useful when the composer wants musicians to play a specific tension array.

These are also commonly referred as "slash chords". A slash chord is simply a chord placed on top of a different bass note. For example:

- D/F♯ is a D chord with F♯ in the bass, and

- A/C♯ is an A chord with C♯ in the bass.

Slash chords generally do not indicate a simple inversion (which is usually left to the chord player's discretion anyway), especially considering that the specified bass note may not be part of the chord to play on top. The bass note may be played instead of or in addition to the chord's usual root note, though the root note, when played, is likely to be played only in a higher octave to avoid "colliding" with the new bass note.

Polychords

[edit]Polychords, as the name suggests, are combinations of two or more chords. The most commonly found form of a polychord is a bichord (two chords played simultaneously) and is written as follows: upper chord/lower chord, for example: B/C (C–E–G—B–D♯–F♯).

Other symbols

[edit]The right slash (/) or diagonal line written above the staff where chord symbols occur is used to indicate a beat during which the most recent chord symbol is understood to continue. It is used to help make uneven harmonic rhythms more readable. For example, if written above a measure of standard time, "C / F G" would mean that the C chord symbol lasts two beats while F and G last one beat each. The slash is separated from the surrounding chord symbols so as not to be confused with the chord-over-a-bass-note notation that also uses a slash. Some fake books extend this slash rhythm notation further by indicating chords that are held as a whole note with a diamond, and indicating unison rhythm section rhythmic figures with the appropriate note heads and stems.

A simile mark in the middle of an otherwise empty measure tells the musician to repeat the chord or chords of the preceding measure. When seen with two slashes instead of one it indicates that the previous measure's chords should be repeated for two further measures, called a double simile, and is placed on the measure line between the two empty bars. It simplifies the job of both the music reader (who can quickly scan ahead to the next chord change) and the copyist (who doesn't need to repeat every chord symbol).

The chord notation N.C. indicates the musician should play no chord. The duration of this symbol follows the same rules as a regular chord symbol. This is used by composers and songwriters to indicate that the chord-playing musicians (guitar, keyboard, etc.) and the bass player should stop accompanying for the length covered by the "No Chord" symbol. Often the "No Chord" symbol is used to enable a solo singer or solo instrumentalist to play a pickup to a new section or an interlude without accompaniment.

An even more stringent indication for the band to tacet (stop playing) is the marking solo break. In jazz and popular music, this indicates that the entire band, including the drummer and percussionist, should stop playing to allow a solo instrumentalist to play a short cadenza, often one or two bars long. This rhythm section tacet creates a change of texture and gives the soloist great rhythmic freedom to speed up, slow down, or play with a varied tempo.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Sources

[edit]- ^ Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn Nadine (2003). Music in Theory and Practice (7th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. p. 78. ISBN 0072942622. OCLC 61691613.

- ^ "The Forum". Sounding Board. Vol. 28. 2001. p. 18.

- ^ Benjamin, Thomas; Horvit, Michael; Nelson, Robert (2008) [2003]. Techniques and Materials of Music (Seventh ed.). Thomson Schirmer. pp. 183–186. ISBN 978-0-495-18977-0.

- ^ Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice. Vol. I (Seventh ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Benward & Saker, p. 77.

- ^ Schoenberg, Arnold (1983). Structural Functions of Harmony, pp. 1–2. Faber and Faber. 0393004783

- ^ Aikin, Jim (2004). A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony: Music Theory for Real-World Musicians (1st ed.). San Francisco: Backbeat Books. pp. 104. ISBN 0879307986. OCLC 54372433.

- ^ Aikin, p. 94.

Further reading

[edit]- Carl Brandt and Clinton Roemer (1976). Standardized Chord Symbol Notation. Roevick Music Co. ISBN 978-0961268428. Cited in Benward & Saker (2003), p. 76.