Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

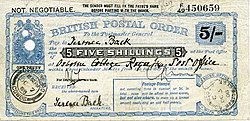

Postal order

View on Wikipedia

A postal order or postal note is a type of money order usually intended for sending money through the mail. It is purchased at a post office and is payable to the named recipient at another post office. A fee for the service, known as poundage, is paid by the purchaser. In the United States, this is known as a postal money order. Postal orders are not legal tender, but a type of promissory note, similar to a cheque.

History

[edit]

In the United Kingdom, the first postal orders went on sale on 1 January 1881.[1] It is a direct descendant of the money order, which had been established by a private company in 1792. During World War I and World War II, British postal orders were temporarily declared legal tender to save paper and labour[2] Postal orders can be bought and redeemed at post offices in the UK, although a crossed postal order must be paid into a bank account.[3] Until April 2006 they came in fixed denominations though an amount of any value less than the next higher fixed denomination could be produced by adding one or more postage stamps in the space on the postal order that was designated for that purpose, but due to increased popularity they were redesigned to make them more flexible and secure. They now have the payee and value added at the time of purchase, making them more like a cheque. There is a fee for using this form of payment. The maximum value of postal order available is £250.00 for a fee of £12.50.[4]

Use in other countries

[edit]

The use of postal orders (or postal notes in some countries) was extended to most countries that are now part of the British Commonwealth of Nations, plus to a few foreign countries such as Jordan, Egypt and Thailand.[5]

United States

[edit]United States Postal Money Service was introduced in 1864 by an act on Congress as a way of sending small amounts of money through the mail.[6][7] By 1865 there were 416 post offices designated as money order offices that had issued money orders to the value of over $1.3 million and by 1882 they had issued orders valued at $113.4 million from 5,491 money order offices.[8]

Currently they facially appear as a draft against an account held by the United States Postal Service, and the United States Postal Service requires a purchaser to know, in advance, where presentment of the instrument will occur. Only special, more expensive United States International Postal Money Orders may be presented abroad. In the United States, international money orders are pink and domestic money orders are green.[9]

Canada

[edit]Canada had its own postal orders (called postal notes) from 1898 until 1 April 1949, when these were discontinued and withdrawn.

A British Forces Post Office in Suffield, Alberta was issuing British postal orders as late as July 2006.

China

[edit]Chinese Imperial Post began issuing postal orders in 1897, the so-called "remittance certificate". After purchase, these certificates are payable at main post offices in China and usually bear franked postage stamps represented as fee. Since 1925, a set of special stamps were used by post offices to issue secured postal orders.[10] Since 1929, Chinese Post have been able to sell international postal orders cashable under UPU protocol in a few other countries including Japan, Britain, France, and the US.

Australia

[edit]

A Defence canteen order was a variant of a postal order used in Australia during World War II. Purchased at a post office, it was payable to an enlisted person in goods from a canteen rather than being a cash instrument.[11]

Collecting

[edit]Postal orders are gaining in popularity as collectibles, especially among numismatists who collect banknotes.

There is an active numismatic organisation in the UK called the Postal Order Society that was established in 1985 with members both domestically and overseas. They hold twice-yearly postal auctions of postal orders and related material from across the British Commonwealth.

Advantages

[edit]Despite competition from cheques and electronic funds transfer, postal orders continue to appeal to customers, especially as a form of payment for shopping on the Internet, as they are drawn on the Post Office's accounts so a vendor can be certain that they will not bounce. They also enable those without a bank account, including minors, to make small financial transactions without the need for cash. Postal workers in the United Kingdom use voided or cancelled orders in their training.[12]

See also

[edit]- George Archer-Shee, whose court case inspired Terence Rattigan's play The Winslow Boy.

- List of countries that have used postal orders

- Promotional postal order

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.postalmuseum.org/blog/140-years-of-postal-orders

- ^ https://www.postalmuseum.org/blog/140-years-of-postal-orders

- ^ "Postal orders". Post Office Ltd. 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ "Fee structure". Post Office Ltd. 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ Reid, Donald M. (1984). "The Symbolism of Postage Stamps: A Source for the Historian" (PDF). Journal of Contemporary History. 19 (2): 223–249. doi:10.1177/002200948401900204. JSTOR 260594. S2CID 159682377.

- ^ Shaw, Christopher W. (2025). "'The Duty of Government': The Politics of the Domestic Postal Money Order, 1837–1911" (PDF). Federal History. 17: 11–33.

- ^ United States Official Postal Guide. Washington DC: United States Post Office Department. July 1925. p. 93.

- ^ Annual Report of the Postmaster General. Washington DC: United States Post Office Department. 18 November 1882. p. 391.

- ^ The United States Postal Service: an American history (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Postal Service. 2020. ISBN 978-0-9630952-4-4. OCLC 1285681619.

- ^ Fuerst, Robert. E (1976). Catalogue of the Money Order Stamps of China (Pagoda Design).

- ^ "1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 1944-45". January 1945.

- ^ "Another view" by Douglas Myall in British Philatelic Bulletin, Vol. 51, No. 5, January 2014, pp. 149–151.

Further reading

[edit]- Lunn, Howard. (1984) A Guide to the History and Values of British Postal Orders 1881-1984. Howard Lunn.

- Lunn, Howard. (1997) Promotional Postal Orders. East Stour, Gillingham: Howard Lunn.

External links

[edit]Postal order

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

A postal order is a prepaid financial instrument issued by national postal services, functioning as a secure method for transmitting a specified amount of money to a recipient via mail. It is typically payable to a designated payee or, in certain variants, to bearer, and is designed for domestic or international money transmission.[6][7] The primary purpose of postal orders is to enable low-cost, reliable money sending without the need for a bank account, making them accessible to unbanked populations and suitable for small remittances, gifts, or payments. This approach promotes financial inclusion by offering a traceable alternative to cash in the mail, reducing risks associated with loss or theft.[6][7] Key characteristics include availability in fixed or variable denominations, often capped at limits such as £250 in the United Kingdom or $1,000 in the United States, with an issuance fee—commonly called poundage—applied based on the amount. Postal orders are not legal tender but serve as promissory notes similar to cheques, and their validity periods vary by issuing authority; for example, indefinite in the United States and 6 months in the United Kingdom, after which redemption in the latter may require additional verification and evidence of identity.[6][7][8] Postal orders are distinguished from broader money orders, which can be issued by banks or private financial providers, by their exclusive issuance through postal networks. In contrast to cheques, which are linked to a personal bank account and can be stopped, postal orders require no such account and provide prepaid certainty of funds upon issuance.[6][7]Types of Postal Orders

Postal orders are categorized by their denomination structure, intended use, and payment mechanisms, with variations adapted to national postal systems and international agreements. Fixed denomination postal orders feature pre-printed values in set amounts, such as the historical UK versions available in increments like 1 shilling to 20 shillings upon their introduction in 1881. These were common until April 2006, when the UK Post Office revamped the system to discontinue fixed denominations in favor of more flexible options.[9] In contrast, variable or open postal orders allow the purchaser to specify a custom amount at issuance, typically within a defined range. For example, in the modern UK system, these orders can be issued for any value from 50p to £250, providing greater convenience for remittances without needing supplementary stamps. This shift emphasizes adaptability to individual needs while maintaining security features.[6] International postal orders adhere to standards set by the Universal Postal Union (UPU), facilitating cross-border transfers with provisions for currency conversion and standardized forms. Under UPU regulations, the amount is expressed in the currency of the issuing country unless a special agreement specifies otherwise, and these orders are often issued on distinct forms for global recognition. A notable example is the pink International Postal Money Order (Form MP1) used by the United States Postal Service for payments to select countries, though issuance was discontinued as of October 2024.[10][11] Specialized postal orders include those tailored for military or defense purposes, such as Australia's WWII-era Defence Canteen Orders, which were issued through post offices in denominations like 5 shillings, 10 shillings, and 20 shillings to enable service members to purchase amenities or gifts. Electronic variants represent a modern adaptation, exemplified by India's Electronic Money Order (eMO), which enables instant electronic transfer of funds up to ₹10,000 via the postal network, replacing traditional paper-based transmission for faster domestic remittances.[12][13] Postal orders also differ in payee designation and negotiability: bearer types, where no specific payee name is inserted, allow payment to any presenter, though this form is restricted in many systems to enhance security. Named payee orders specify a recipient, reducing fraud risk. Additionally, crossed postal orders, marked with two parallel lines, are payable only into a bank or building society account in the payee's name, while uncrossed versions function like cash and can be redeemed over the counter.[14][6]History

Origins and Introduction

The postal order was introduced in the United Kingdom on January 1, 1881, as a secure and low-cost method for remitting small sums of money through the mail, serving as a simpler alternative to the existing money order system, which was deemed unprofitable for low-value transactions under 20 shillings.[15] The initiative was championed by Postmaster General Henry Fawcett, who oversaw its implementation following parliamentary approval in 1880, building on proposals dating back to 1874 from George Chetwynd, the Receiver and Accountant General of the Post Office, who advocated for a bearer instrument payable at any post office to facilitate easier cashing.[16][17] This innovation addressed the risks associated with mailing cash informally, which had become increasingly common among the working class amid limited access to traditional banking services during the late 19th century.[3] Initial postal orders featured fixed denominations ranging from 1 shilling to 20 shillings, with poundage fees scaled for affordability: half a penny for orders up to 2s 6d, one penny for 5s to 7s 6d, and two pence for 10s to 20s, payable at any UK post office upon presentation.[15] Users could add small amounts by affixing postage stamps to the order, enhancing flexibility for exact sums, though the core design emphasized simplicity and security through serial numbering and unique watermarks.[18] Adoption was swift, driven by the system's accessibility for unbanked individuals, particularly laborers and families separated by distance; in the first year, over 4 million units were issued, valued at more than £2 million, reflecting strong public uptake as a response to socioeconomic barriers in financial services.[15] The UK's model exerted early influence on global postal finance, particularly in British colonies and dominions, where similar systems were adopted to extend secure remittances within the Empire, often through reciprocal agreements for issuance and redemption.[16] Notably, the United States had pioneered a related money order service in 1864 during the Civil War, aimed at enabling soldiers to send funds home safely, though its formalization as a widespread postal product evolved more gradually compared to the UK's streamlined 1881 rollout.[19] By 1885, UK issuance had surged to 25 million orders annually, underscoring the rapid international ripple effects of this postal innovation.[16]Evolution and Key Changes

During World War I, the British government declared postal orders legal tender from 10 August 1914 until 3 February 1915 to conserve paper and labor while withdrawing gold coinage from circulation.[16] This wartime measure highlighted their role as emergency currency, though the status was short-lived as fears of currency circulation issues did not materialize.[3] In the 20th century, several countries discontinued postal orders amid rising electronic banking adoption. Canada ceased issuing postal orders on 1 April 1949, shifting focus to other remittance services. In Ireland, An Post ended postal orders in October 2001 following a 60% sales drop over the prior decade, driven by increased use of cheques, banking cards, and more efficient point-of-sale technologies; the euro changeover further accelerated this retirement.[20] These discontinuations reflected broader transitions to digital financial tools. The 21st century brought updates to adapt postal orders to modern needs. In the United Kingdom, Royal Mail redesigned postal orders in April 2006, introducing on-demand printing for variable amounts from 50p to £1,000, barcodes for tracking, and a cheque-like format to enhance usability and security.[9] India Post launched electronic money orders (eMO) in October 2008, enabling instant electronic transmission up to ₹5,000 with doorstep delivery, replacing slower traditional methods and expanding access in rural areas.[21] Internationally, the Universal Postal Union standardized procedures for cross-border postal orders through its 1929 London Convention and subsidiary agreements, facilitating reciprocal exchange among member states.[22] Peak usage occurred in the late 19th century, with U.S. postal money orders reaching over $110 million in annual value by 1890 across thousands of offices.[19] Issuance declined post-1990s as electronic transfers and banking alternatives proliferated, contributing to overall letter-post volume reductions of up to 9% annually by the mid-2010s.[23]Mechanics of Use

Issuing and Payment

To issue a postal order, the purchaser must visit a participating post office branch, where they specify the desired amount and provide the payee's name, as postal orders are not issued in bearer form in countries like the United Kingdom. The staff then issues the postal order, which may be designated as crossed (payable only through a bank account) or uncrossed (payable in cash at any post office), depending on the buyer's preference and local options. The buyer pays the face value of the order plus an issuance fee, receives the instrument and a receipt for record-keeping, and can then mail or deliver it to the recipient. This process ensures the order is pre-funded and secure for transfer without requiring the sender's bank details.[6][7] Issuance fees, often called poundage or commission, are structured in tiers based on the order's value to cover administrative costs, with maximum limits on the amount per order varying by country. In the United Kingdom, for instance, fees start at 50p for orders valued from 50p to £4.99, rise to £1 for £5 to £9.99, apply at 12.5% of the face value for £10 to £99.99, and are capped at £12.50 for orders up to the £250 maximum. In the United States, the United States Postal Service charges $2.55 for domestic money orders up to $500 and $3.60 for amounts from $500.01 to $1,000, the per-order limit. These fees reflect operational expenses and are subject to periodic adjustments, but they remain fixed regardless of distance or delivery method.[6][7] Documentation for issuance typically involves completing a simple form with the sender's details, payee information, and amount, signed by the purchaser; no extensive identification is required for standard low-value orders, though photo ID may be requested for higher amounts to prevent fraud. In modern systems, such as India's electronic money order (eMO) service, issuance can occur digitally via the India Post mobile app or e-Post Office portal, where users register, select the amount (with limits up to Rs. 10,000 for domestic orders), enter payee details, and confirm payment without visiting a branch. This electronic option streamlines the process for instant booking and tracking, maintaining the same core requirements as physical issuance.[13] Payment for the postal order is accepted in cash at most locations, with some post offices also permitting debit card transactions to accommodate non-cash users; credit cards are generally not allowed, and no direct linkage to the purchaser's bank account is needed, preserving anonymity and accessibility. For electronic issuance, payments can be made via net banking, UPI, or cards through the portal, adding convenience while adhering to secure transaction protocols. These methods ensure broad usability, particularly for unbanked individuals seeking a reliable remittance tool.[7][13]Redemption and Transfer

Postal orders are redeemed by presenting the instrument at a post office branch, where the payee endorses it by signing the counterfoil or back to validate ownership, allowing payout in cash or deposit into a bank account.[6] Uncrossed postal orders can typically be cashed at any participating post office without restriction, while crossed ones—marked with two parallel lines—are redeemable only through deposit to a specified bank account, enhancing security against unauthorized cashing.[6] In the United States, similar redemption occurs at post offices or authorized retailers, requiring valid photo identification such as a driver's license, with payouts limited to cash or check deposit.[8] Transfer of a postal order to a third party is facilitated through endorsement, where the original payee signs the reverse side, effectively assigning it like a negotiable instrument, though some jurisdictions limit endorsements to prevent multiple transfers.[24] Crossing the postal order at issuance designates it as "account payee only," restricting redemption to the named recipient's bank and prohibiting further endorsement for cash.[6] Redirection via mail is possible in certain systems, such as the UK's, where the order can be forwarded to another branch for a nominal fee, but this requires the sender's original receipt for verification.[24] Security features integral to postal orders include unique serial numbers for tracking and verification, holograms or watermarks to deter counterfeiting, and expiry dates—typically six months from issuance in the UK, after which redemption may incur a fee or require special approval. In the United States, as of February 2025, redesigned money orders include enhanced security features like improved watermarks, security threads, and QR codes for verification. Non-transferable inks and validation checks at redemption points further prevent alterations or fraud, with post offices refusing payment if the instrument appears defaced or tampered.[6] In the US, additional safeguards like a security thread and printed amount in multiple places aid in authenticity confirmation, supported by a national verification hotline at 1-866-459-7822.[25][26] For lost or stolen postal orders, claimants must submit an affidavit of loss and indemnity bond to protect the issuer, often after a waiting period to confirm non-redemption—30 days in the US and 15 days in the UK for mailed items.[8] Replacement involves providing the purchase receipt and serial number; in the UK, a P58 form is filed with Royal Mail for transit losses, while US inquiries use PS Form 6401, potentially taking up to 60 days for resolution.[24] Stolen orders require a police crime reference number for refund eligibility if uncashed.[24] International redemption follows Universal Postal Union (UPU) protocols under the Postal Payment Services Agreement, enabling cross-border payout at destination post offices in local currency equivalent, with inquiries or rectifications processed via standardized forms like MP 3 for errors.[2] Participating designated operators exchange data for verification, ensuring secure settlement within six working days of deposit, though as of October 1, 2025, the United States Postal Service has discontinued both the issuance of outbound international money orders (phased out earlier) and the cashing of inbound international postal money orders, while continuing to support domestic money orders.[27][11]Advantages and Limitations

Benefits for Users

Postal orders provide essential accessibility for users without bank accounts, enabling secure money transfer through widespread post office networks that serve unbanked and rural populations globally.[28] These services are particularly valuable in areas with limited banking infrastructure, where post offices act as trusted community hubs for financial transactions.[29] The security of postal orders stems from their prepaid nature and backing by national postal authorities, minimizing risks such as bounced payments or fraud compared to personal checks. Features like watermarks, holographic strips, and the ability to cross orders for payee-only redemption enhance protection, while free cashing at post offices ensures reliable access without additional costs.[19] This makes them suitable for online payments where credit cards are unavailable or undesired, as they can be mailed trackably through the postal system.[19] Cost-effectiveness is a key advantage for small-value transfers, with fees typically low—often under 2% of the amount—avoiding the higher charges of wire transfers or private money services for domestic use.[19] This affordability supports everyday needs like bill payments or small remittances without eroding the principal value. Convenience arises from immediate issuance at post offices, allowing users to obtain and send funds on the spot, integrated with postal delivery for remote recipients. Historically, postal orders have facilitated remittances, enabling immigrants and migrant workers to send money home reliably through established postal channels.[30] Additional perks include options for anonymity in issuance, where personal details may not be required, preserving user privacy in sensitive transactions.[19]Drawbacks and Risks

One significant drawback of postal orders is the additional cost imposed by issuance fees, often referred to as poundage, which can range from fixed amounts for small values to percentages of the order's face value, effectively increasing the overall expense for users. In the United Kingdom, for instance, fees are £0.50 for orders between 50p and £4.99, £1 for £5 to £9.99, 12.5% for £10 to £99.99, and capped at £12.50 for £100 to £250, making higher-value orders relatively more burdensome. In the United States, the U.S. Postal Service charges $2.55 for domestic money orders up to $500 and $3.60 for $501 to $1,000 as of July 2025; international money orders were discontinued for issuance effective October 1, 2024.[6][7][31] These costs are exacerbated for cross-border transactions, where additional surcharges and currency conversion fees apply, potentially doubling the effective rate.[8] Delays inherent in the postal system represent another limitation, as transit times typically range from 3 to 7 days domestically, depending on service levels and location, which can disrupt urgent payments compared to instant electronic transfers. Furthermore, postal orders have expiry periods after which they may become invalid or subject to forfeiture, leading to potential loss of value if not redeemed promptly. In the UK, orders expire after 6 months, after which redemption is at the issuer's discretion and may require identity verification. In India, unpaid domestic money orders are forfeited after 3 years from booking. While U.S. Postal Service money orders do not expire, prolonged inactivity with other issuers can trigger dormancy fees that erode the principal.[6][13][8] Postal orders carry several risks, including vulnerability to theft or loss during mail handling, despite mitigation measures like crossing the order to restrict cashing. If lost or stolen, users must wait periods such as 15 days in the UK to apply for replacement via a P58 form, requiring proof of purchase and potentially a police report for theft, which delays recovery and incurs administrative hassles. Forgery remains a concern, as criminals can alter or counterfeit orders, with the U.S. Postal Service's controls sometimes failing to detect fraud promptly, leading to financial losses for victims or issuers. Additionally, unlike savings accounts, postal orders accrue no interest, meaning the funds remain static without earning returns during transit or holding periods.[6][32][33] Key limitations include relatively low maximum values, rendering postal orders unsuitable for substantial transfers; the UK caps them at £250 per order, the U.S. at $1,000 domestically, and India at ₹10,000. This restricts their utility for larger sums, often necessitating multiple orders and compounding fees. Moreover, acceptance by merchants and businesses is declining in favor of digital payments, with many retailers no longer processing postal orders due to verification challenges and preferences for faster methods. In the UK, for example, they are primarily used for mail-order purchases or government fees but are not universally accepted.[6][8][13][34] In the digital era, physical handling introduces further risks, such as damage from mishandling or exposure to elements during transit, which can invalidate the order. The reliance on paper also contributes to environmental impacts, including resource consumption for production and disposal; globally, postal services generate significant paper waste, but still contribute to deforestation and emissions through non-recycled portions. Security features like watermarks help mitigate forgery but do not eliminate these inherent vulnerabilities.[35]Usage in Selected Countries

United Kingdom

Postal orders were first introduced in the United Kingdom on 1 January 1881, marking the world's inaugural issuance of this financial instrument as a secure alternative to sending cash through the mail.[3] Initially available in fixed denominations, they were designed to facilitate small-value remittances, building on the existing money order system while offering greater accessibility at post offices.[3] During both World War I and World War II, the British government designated postal orders as legal tender to conserve paper and labor resources amid wartime shortages, allowing them to circulate as cash equivalents for essential transactions.[36] This measure, first implemented in 1914 and reinstated in 1939, temporarily elevated their role beyond mere remittances, though it was discontinued post-war as economic conditions stabilized. In the early 20th century, particularly from 1914 to 1920, issuance was restricted to a maximum value of £1 to manage currency circulation during the conflicts.[36] A significant redesign occurred in April 2006, transitioning from fixed-value formats to variable amounts printed on demand at the point of purchase, with a maximum limit of £250.[9] This update addressed modern needs by eliminating the need for multiple orders to reach desired sums and incorporated enhanced security features, such as watermarks and microprinting. Historically, postal orders could be uprated by affixing postage stamps to designated areas on the counterfoil; for instance, a 1969 Irish 9-shilling order exemplifies this practice in the British Isles tradition.[9] As of 2025, postal orders continue to be issued exclusively by Post Office Ltd. at over 11,500 branches nationwide, remaining a viable option for individuals without bank accounts.[6] They are available in any amount from £0.50 to £250, with issuance fees structured as follows:| Order Value | Fee |

|---|---|

| £0.50–£4.99 | 50p |

| £5.00–£9.99 | £1.00 |

| £10.00–£99.99 | 12.5% of value |

| £100.00–£250.00 | Up to £12.50 |

United States

In the United States, postal money orders were first introduced by the Post Office Department in 1864 as a secure method for transmitting funds through the mail, primarily to assist Civil War soldiers in sending their pay home to families without the risks associated with carrying cash. This innovation addressed a critical need during wartime, when traditional banking options were limited, and it rapidly expanded in usage post-war as the population grew and mail volume increased. By 1890, the system had scaled significantly, with the annual value of issued domestic money orders exceeding $110 million, reflecting its role as an early form of accessible financial service for everyday transactions.[38] As of 2025, the United States Postal Service (USPS) continues to offer domestic postal money orders on green security forms, with a maximum value of $1,000 per order to mitigate fraud risks. Fees are tiered by amount: $2.55 for orders from $0.01 to $500, and $3.60 for $500.01 to $1,000, making them an affordable option for secure payments. International postal money orders, previously issued on pink forms with a $700 limit and a $2.40 fee, ceased sales effective October 1, 2024, and USPS stopped cashing all international money orders effective October 1, 2025, though existing domestic redemptions remain available at post offices. Postal military money orders, intended for use at military facilities, are issued at a reduced fee of $0.84 with no value limit specified beyond standard practices.[7][39][8] These money orders are widely used for practical purposes such as paying rent, utility bills, or other obligations where recipients prefer guaranteed funds over personal checks or cash. They are available for purchase with cash or debit cards at more than 31,000 USPS retail locations, including post offices and contract stations, ensuring broad accessibility across the country. To verify a money order's validity or status—such as whether it has been cashed—users can call the USPS Money Order Verification System at 1-866-459-7822, providing the serial number, issue date, and value, or check online via the USPS tools portal.[7][40] A distinctive feature of USPS money orders is their standardized replacement process for lost, stolen, or damaged items, which prioritizes customer protection through verification. For lost or stolen orders, customers must present the original receipt and complete PS Form 6401 (Money Order Inquiry) at a post office, incurring a $21.00 processing fee; USPS investigates within 30 days and issues a replacement if confirmed, though full resolution may take up to 60 days. Damaged money orders can be exchanged immediately with the receipt at no additional cost, provided the damage does not obscure key details like the serial number. These procedures, combined with enhanced security features like watermarks and microprinting on the 2025 redesigned forms, underscore the system's emphasis on reliability and fraud prevention.[7][8][26]India

India's postal money order system, managed by India Post, traces its origins to the British colonial era, when it was introduced on January 1, 1880, as a secure method for domestic remittances.[41] This service evolved significantly in the digital age, with electronic money orders (eMO) launched in October 2008 to enable real-time electronic transmission and faster delivery compared to traditional paper-based orders.[42] By the 2010s, traditional money orders were phased out in favor of eMO, reflecting India Post's shift toward digitized financial services.[43] As of 2025, eMO remains a core offering for domestic transfers, allowing remittances from ₹1 to a maximum of ₹10,000 per order, with no fractional rupees permitted.[13] Fees are structured at ₹1 for every ₹20 or fraction thereof, making it an affordable option for small-value transactions.[44] Users can book eMO online through the ePost Office portal, which supports registration, payment via integrated UPI systems, and real-time tracking of status and delivery.[45] This service is particularly vital in rural India, where it facilitates millions of annual remittances to unbanked households, leveraging India Post's extensive network of approximately 1.65 lakh post offices—90% of which are rural—to bridge financial inclusion gaps.[46] Integration with digital tools like UPI for seamless payments and DIGIPIN for precise location-based addressing further enhances accessibility and efficiency.[47] A distinctive feature of India's system is the Electronic Indian Postal Order (eIPO), introduced in 2013 primarily for Indian citizens abroad but extended domestically, allowing online purchase for payments such as court fees and Right to Information (RTI) applications.[48] eIPOs are generated via the ePost Office portal, requiring attachment as a printout or digital file with applications, and are designed for single-use to prevent misuse.[49] Unpaid money orders, including eMOs, expire after three years from the booking date, at which point the amount is forfeited to the government, though postmasters may exercise discretion for delayed payments if feasible.[50] This expiry policy underscores the system's emphasis on timely redemption while maintaining fiscal discipline.Canada

Postal notes, a form of postal order, were introduced in Canada on August 4, 1898, by the Post Office Department to enable secure remittance of small sums through the mail. The service was available at post offices nationwide, where customers could purchase pre-printed forms in denominations ranging from 10 cents to $100, payable to the bearer or a specified recipient.[51] The design and functionality closely mirrored the British postal order system, providing a low-cost alternative to private money orders for everyday transfers such as wages or family support.[51] Forms were printed in both English and French to reflect Canada's bilingual nature, ensuring accessibility across linguistic communities. The service proved popular for modest transactions until its discontinuation on April 1, 1949, coinciding with the unification of postal services between Canada and Newfoundland and broader modernization efforts amid expanding commercial banking options.[52] This termination aligned with post-war developments that favored bank-issued money orders, which offered greater flexibility and integration with the growing financial sector.[52] Examples of these notes are prized by philatelists due to their historical significance and relatively low survival rate, with many destroyed or lost over time.Australia

Australia's use of postal orders has been limited and specialized, without a widespread domestic system comparable to that in the United Kingdom. Historically, the country relied on influences from British colonial practices but did not establish a national postal order service for general public use. Instead, during World War II, a variant known as Defence Canteen Orders was introduced specifically for military personnel. These orders, issued by the Australian Defence Canteens Service in collaboration with the Postal Department, allowed families and supporters to send funds to enlisted troops for purchasing amenities at canteens, enabling recipients to select their own comforts such as tobacco or sweets.[53] Denominations ranged from 2 shillings to 20 shillings, with higher values up to £5 available in some cases, and they were purchased at post offices across Australia.[54] This system, operational primarily in the 1940s, served troop welfare purposes amid wartime demands but was not extended to civilian applications.[12] In Australian territories, such as Papua and New Guinea, overprinted British postal orders were utilized during the early to mid-20th century to facilitate local transactions. These orders bore overprints indicating payability "only in the Territory of Papua and Commonwealth of Australia," adapting imported British forms for regional use due to the lack of a fully independent issuance system. Issuance volumes remained low overall, reflecting the niche military and territorial focus rather than broad adoption, and these instruments were not integrated into everyday domestic remittances. The wartime canteen orders, in particular, became rare artifacts post-war, with surviving examples often preserved for their historical significance in supporting Australian forces.[55] As of 2025, Australia Post does not issue traditional postal orders, having shifted emphasis to alternative financial services. The organization provides domestic money orders through post offices and partnerships with banks, but these are distinct from postal-specific orders and are treated as general financial supplies without the historical postal guarantee features.[56] International money orders have been discontinued, with Australia Post promoting electronic transfers and digital payment options instead. This evolution underscores the rarity of physical postal orders in modern Australia, confined largely to historical military contexts without national rollout.[57]China

The Imperial Chinese Post, established in 1897, issued postal orders as an essential financial service to enable secure domestic money transfers amid the modernization of the postal system under the Qing dynasty.[58] These orders played a key role in facilitating remittances and trade transactions, particularly as foreign trade expanded in coastal ports, allowing merchants to send funds reliably through the emerging national network.[59] Following the Republic of China's accession to the Universal Postal Union in 1914, postal services gained international recognition, with overprinted orders appearing in the 1910s to adapt to currency changes and regional needs during political transitions.[60] International postal orders were formalized in 1929, enabling cashing in other UPU member countries and integrating China into global remittance flows.[61] This development supported overseas Chinese communities in sending funds home, contributing significantly to familial and economic ties amid early 20th-century migration and trade.[62] After the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, China Post assumed control, maintaining and expanding the system under state oversight to promote financial inclusion and cross-border commerce.[63] As of 2025, China Post continues to provide domestic and international money orders through integration with UPU networks, including electronic tracking for enhanced security and transparency in transfers. Historically, postal orders bolstered China's role in international trade by enabling reliable fund movements for expatriate workers and merchants, a function that persists in supporting modern cross-border economic activities.[64][65]Decline and Modern Alternatives

Reasons for Decline

The decline of postal orders globally since the 1990s has been driven primarily by the rise of digital banking and electronic communication, which have displaced traditional physical mail-based financial services. Electronic diversion, where physical mail is replaced by digital alternatives such as online transfers and email, has been identified as the key factor in the ongoing reduction of mail volumes, including those for money orders and remittances.[66] For instance, the shift to digital options has rendered paper-based money orders obsolete in many contexts, as faster and cheaper electronic methods like online banking platforms reduce the need for physical delivery through postal networks.[67] This transition is accelerated by the broader adoption of electronic communications, particularly digital letters from public institutions, which substitute for postal services and lead to decreased reliance on mailed financial instruments.[68] Economic shifts, including greater access to banking and the proliferation of automated clearing house (ACH) systems in countries like the United States, have further diminished the demand for postal orders as a remittance tool. In the US, First-Class Mail volumes, which include letters and large envelopes often used for postal orders, fell by 50 percent between fiscal years 2008 and 2023, from 92 billion pieces to 46 billion, reflecting broader trends in electronic substitution for remittances and payments.[66] The Great Recession of 2008 intensified this decline, as the economic downturn and subsequent internet-driven shifts accelerated the move toward electronic payments, reducing the overall volume of mailed financial transactions.[69] Intensified competition from private money transfer services has also contributed significantly to the erosion of postal orders' market share. Services like Western Union expanded during the late 2000s, capturing a larger portion of the remittance market amid economic pressures and the growing preference for non-postal alternatives, which offer quicker processing without reliance on mail infrastructure.[70] This competitive landscape, combined with inefficiencies in postal operations and regulatory ambiguities, has pressured public postal providers to lose ground to more agile private entities.[71] Regional factors in Europe have exacerbated the global trend, with widespread discontinuations and volume drops signaling the obsolescence of postal orders. Letter mail volumes across Europe have contracted sharply, influenced by digital disruption and economic changes, leading several operators to phase out or restrict such services.[72] The COVID-19 pandemic further boosted this shift by accelerating digital adoption, resulting in estimated letter mail volume drops of 12 to 26 percent in Europe during the crisis period, as lockdowns and remote work reduced physical mail needs.[73] In parallel, cross-border postal exchanges declined by 21 percent globally during the early pandemic stages, underscoring the vulnerability of mail-dependent services like postal orders to health-driven digital pivots.[74]Digital Substitutes

In the modern era, digital substitutes for postal orders have largely supplanted traditional paper-based instruments, offering faster, more secure, and cost-effective alternatives for both domestic and international money transfers. These electronic methods leverage mobile apps, online platforms, and blockchain technology to facilitate peer-to-peer (P2P) payments, remittances, and other transactions, particularly appealing to users seeking convenience without the need for physical mail. For domestic transfers, apps such as Venmo and Zelle provide instant P2P payments with minimal or no fees when using linked bank accounts or debit cards. Venmo, owned by PayPal, enables users to send money via social features like split bills, with standard transfers completing in minutes at no cost domestically, though instant transfers to bank accounts incur a 1.75% fee. Zelle, integrated directly into many U.S. banks, supports fee-free transfers up to $500 per day for most users, emphasizing speed and security through email or phone number-based sending, making it a direct replacement for low-value postal orders. Internationally, services like Wise (formerly TransferWise) and Remitly have become popular for low-cost remittances, often charging 0.4% to 0.6% of the transfer amount plus small fixed fees, compared to traditional postal money orders that can cost up to $50 in issuing fees alone for cross-border sends. For example, Wise uses the mid-market exchange rate with transparent fees starting at 0.43% for many currency pairs, allowing recipients to receive funds in local bank accounts or cash pickup points within hours.[75] Remitly similarly offers economy transfers at $3.99 for amounts under $1,000 to countries like India or the Philippines, with express options delivering in minutes for slightly higher fees, significantly undercutting postal alternatives that involve mailing delays and higher processing costs.[76] Some postal services have integrated digital elements to modernize offerings. In India, the Electronic Money Order (eMO) system transmits funds electronically between post offices, reducing delivery time from days to hours and charging a 5% fee on the amount, with recent UPI-UPU integration enabling seamless cross-border remittances via post offices using India's Unified Payments Interface for faster, low-cost global transfers.[13] In contrast, the United States Postal Service (USPS) continues to rely on physical money orders without an electronic equivalent, though services like Informed Delivery provide mail previews rather than digital payment options.[7] Emerging blockchain-based solutions, such as those on the Stellar network, target the unbanked population for remittances by enabling near-instant, low-fee transactions across borders. Stellar facilitates cross-border payments with fees under 0.00001 XLM (fractions of a cent) per transaction, partnering with organizations to serve regions with high unbanked rates, like sub-Saharan Africa, where remittances exceed $50 billion annually.[77] Global adoption of cryptocurrency remittances is projected to reach 3-5% of total flows by 2025, driven by its focus on financial inclusion for the 1.3 billion unbanked adults worldwide.[78] These digital substitutes offer key advantages over postal orders, including real-time processing, end-to-end tracking via apps or blockchain ledgers, and elimination of physical risks like loss or theft during transit.[79] However, challenges persist, such as the digital divide that excludes populations without smartphones or internet access, potentially limiting reach in rural or low-income areas where postal orders once thrived.[80]Collecting

Philatelic Value

The hobby of collecting postal orders as philatelic items emerged in the late 20th century, gaining organized momentum with the founding of the Postal Order Society on May 1, 1985, a non-profit organization dedicated to the study and pursuit of postal orders worldwide. This society has played a key role in fostering interest among collectors, facilitating exchanges and research into historical issues. Auctions for rare postal orders have since become a notable aspect of the market, with early examples like the 1881 first-issue orders commanding significant prices; for instance, the inaugural one-shilling order bearing serial number 000001 sold for £4,485 at a 2010 auction, highlighting the premium placed on first-day and low-denomination rarities.[81] Valuation of postal orders in philatelic collections depends on several key factors, including overall condition, original denomination, presence of overprints or counterfoils, and historical significance. Collectors prioritize items in fine to very fine condition, free from creases, tears, or discoloration, as these directly influence market worth; higher denominations, such as the £1 values from 1881, often fetch more due to their scarcity and era-specific appeal. Specialized catalogs like the Higgins & Gage World Postal Stationery Catalog provide standardized pricing and identification, aiding collectors in assessing rarity and variants such as surcharged or specimen overprints. Historical context, such as ties to pivotal events or early issuance dates, further elevates value, with auctions reflecting these elements through competitive bidding. Global interest in postal order collecting centers on British Commonwealth issues, which are particularly popular due to their shared design heritage and colonial-era variations, attracting enthusiasts from the UK, Canada, Australia, and beyond. Societies like the Postal Order Society organize annual sales and exchanges, promoting accessibility and community-driven pricing that sustains market activity for these items. Preservation practices for postal orders emphasize archival methods to maintain their integrity, including storage in acid-free folders or boxes to prevent acid degradation from paper or adhesives. Collectors are advised to control environmental factors like humidity (ideally 40-50%) and temperature (around 68-72°F), avoiding direct sunlight or PVC materials that can cause discoloration. Digital scanning offers a supplementary tool for record-keeping, allowing high-resolution imaging without handling the originals, thus minimizing wear while enabling sharing within collector networks.Notable Examples

One of the most prized items in postal order collecting is the 1865 Chicago black-bordered envelope postmarked "CHICAGO ILLS. M.O.B. / APR 22 ‘65," which represents the earliest known dated cover from the first year of U.S. postal money order service and coincides with national mourning following President Abraham Lincoln's assassination.[82] This cover, featuring the Money Order Business (M.O.B.) cancellation, highlights the early operational challenges of the system launched in 1864 with just 419 offices nationwide, making such artifacts exceptionally scarce due to their limited production and historical context.[82] In the United Kingdom, the inaugural postal orders issued on January 1, 1881, are highly sought after for their pioneering role as the world's first such financial instruments, with ten denominations featuring unique local serial numbering, elongated shapes, and anti-forgery watermarks like "POSTAL ORDER / ONE SHILLING."[81] A standout example is the one-shilling postal order bearing serial number 000001, issued at the Lombard Street office on the launch date; only six are known to exist, and one sold at auction in 2010 for £4,485, underscoring its rarity and significance in philatelic history.[81] Another notable U.S. specimen is the 1875 Swiss international postal order receipt for $10, postmarked "CHICAGO M.O.B. / SEP 13 1875," which exemplifies early cross-border usage under the 1875 Treaty of Bern and remains rare due to the nascent international money order network.[82] Similarly, the 1882 Cherry Creek, Nevada, money order advice form illustrates the expansion of services to remote areas, valued by collectors for its insight into frontier postal operations.[82] These examples emphasize how early, documented, or thematically significant postal orders—often tied to postmarks, historical events, or international agreements—drive philatelic interest over mere denomination varieties.References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Post%2C_and_Postal_Service