Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

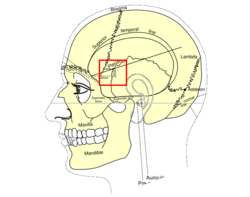

Pterion

View on Wikipedia

| Pterion | |

|---|---|

Side view of head, showing surface relations of bones (Pterion labeled at center) | |

Side view of the skull with arrow pointing to the Pterion | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pterion |

| TA98 | A02.1.00.019 |

| TA2 | 421 |

| FMA | 264720 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The pterion is the region where the frontal, parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones join.[1] It is located on the side of the skull, just behind the temple. It is also considered to be the weakest part of the skull, which makes it clinically significant, as if there is a fracture around the pterion it could be accompanied by an epidural hematoma.

Structure

[edit]The pterion is located in the temporal fossa, approximately 2.6 cm behind and 1.3 cm above the posterolateral margin of the frontozygomatic suture.[2]

It is the junction between four bones:

- the parietal bone.

- the squamous part of temporal bone.

- the greater wing of sphenoid bone.

- the frontal bone.

These bones are typically joined by five cranial sutures:

- the sphenoparietal suture joins the sphenoid and parietal bones.

- the coronal suture joins the frontal bone to the sphenoid and parietal bones.

- the squamous suture joins the temporal bone to the sphenoid and parietal bones.

- the sphenofrontal suture joins the sphenoid and frontal bones.

- the sphenosquamosal suture joins the sphenoid and temporal bones.

Clinical significance

[edit]Hematoma

[edit]The pterion is known as the weakest part of the skull.[3] The anterior division of the middle meningeal artery runs underneath the pterion.[4] Consequently, a traumatic blow to the pterion may rupture the middle meningeal artery causing an epidural haematoma. The pterion may also be fractured indirectly by blows to the top or back of the head that place sufficient force on the skull to fracture the pterion.

Surgery

[edit]The pterion is a structural landmark for neurosurgical approach to middle cerebral artery aneurysms.[5]

Etymology

[edit]The pterion receives its name from the Ancient Greek root πτερόν pteron, meaning 'wing'. In Greek mythology, Hermes, messenger of the gods, was enabled to fly by winged sandals, and wings on his head, which were attached at the pterion.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 182 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 182 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ R.M. McMinn.Last's anatomy regional and applied, 9th edition. Edinburgh (UK): Churchill Livingstone; 1994. Page 645

- ^ Siyan, MA; Louisa J.M. Baillie; Mark D. Stringer (April 2012). "Reappraising the surface anatomy of the pterion and its relationship to the middle meningeal artery". Clinical Anatomy. 25 (3): 330–339. doi:10.1002/ca.21232. PMID 21800374. S2CID 24390399.

- ^ Garner, Jeff; Goodfellow, Peter (2004). Questions for the MRCS Vivas. p. 123. ISBN 9780340812921.

- ^ Weston, Gabriel (22 August 2011). "Mapping the Body: The Temple". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Urzì, Filippo; Iannello, Annalisa; Torrisi, Antonio; Foti, Pietro; Mortellaro, Nicola Filippo; Cavallaro, Marco (1 April 2003). "Morphological variability of pterion in the human skull". Italian Journal of Anatomy and Embryology = Archivio Italiano di Anatomia ed Embriologia. 108 (2): 83–117. ISSN 2038-5129. PMID 14503657.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy figure: 22:01-04 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Diagram - look for #24 (source here)