Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Temporal bone

View on WikipediaThis article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (January 2024) |

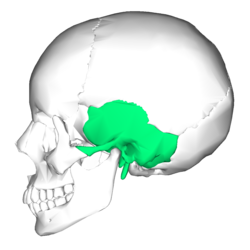

| Temporal bone | |

|---|---|

Position of temporal bone (shown in green) | |

Animation of the temporal bone | |

| Details | |

| Articulations | Occipital, parietal, sphenoid, mandible and zygomatic |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os temporale |

| MeSH | D013701 |

| TA98 | A02.1.06.001 |

| TA2 | 641 |

| FMA | 52737 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The temporal bone is a paired bone situated at the sides and base of the skull, lateral to the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex.

The temporal bones are overlaid by the sides of the head known as the temples where four of the cranial bones fuse. Each temple is covered by a temporal muscle. The temporal bones house the structures of the ears. The lower seven cranial nerves and the major vessels to and from the brain traverse the temporal bone.

Structure

[edit]The temporal bone consists of four parts—the squamous, mastoid, petrous and tympanic parts.[1][2] The squamous part is the largest and most superiorly positioned relative to the rest of the bone. The zygomatic process is a long, arched process projecting from the lower region of the squamous part and it articulates with the zygomatic bone. Posteroinferior to the squamous is the mastoid part. Fused with the squamous and mastoid parts and between the sphenoid and occipital bones lies the petrous part, which is shaped like a pyramid. The tympanic part is relatively small and lies inferior to the squamous part, anterior to the mastoid part, and superior to the styloid process. The styloid, from the Greek stylos, is a phallic shaped pillar directed inferiorly and anteromedially between the parotid gland and internal jugular vein.[3]

Borders

[edit]Development

[edit]The temporal bone is ossified from eight centers, exclusive of those for the internal ear and the tympanic ossicles: one for the squama including the zygomatic process, one for the tympanic part, four for the petrous and mastoid parts, and two for the styloid process. Just before the end of prenatal development [Fig. 6] the temporal bone consists of three principal parts:

- The squama is ossified in membrane from a single nucleus, which appears near the root of the zygomatic process about the second month.

- The petromastoid part is developed from four centers, which make their appearance in the cartilaginous ear capsule about the fifth or sixth month. One (proötic) appears in the neighborhood of the eminentia arcuata, spreads in front and above the internal auditory meatus and extends to the apex of the bone; it forms part of the cochlea, vestibule, superior semicircular canal, and medial wall of the tympanic cavity. A second (opisthotic) appears at the promontory on the medial wall of the tympanic cavity and surrounds the fenestra cochleæ; it forms the floor of the tympanic cavity and vestibule, surrounds the carotid canal, invests the lateral and lower part of the cochlea, and spreads medially below the internal auditory meatus. A third (pterotic) roofs in the tympanic cavity and antrum; while the fourth (epiotic) appears near the posterior semicircular canal and extends to form the mastoid process (Vrolik).

- The tympanic ring is an incomplete circle, in the concavity of which is a groove, the tympanic sulcus, for the attachment of the circumference of the eardrum (tympanic membrane). This ring expands to form the tympanic part, and is ossified in membrane from a single center which appears about the third month. The styloid process is developed from the proximal part of the cartilage of the second branchial or hyoid arch by two centers: one for the proximal part, the tympanohyal, appears before birth; the other, comprising the rest of the process, is named the stylohyal, and does not appear until after birth. The tympanic ring unites with the squama shortly before birth; the petromastoid part and squama join during the first year, and the tympanohyal portion of the styloid process about the same time [Fig. 7, 8]. The stylohyal does not unite with the rest of the bone until after puberty, and in some skulls never at all.

Postnatal development

[edit]Apart from size increase, the chief changes from birth through puberty in the temporal bone are as follows:

- The tympanic ring extends outward and backward to form the tympanic part. This extension does not, however, take place at an equal rate all around the circumference of the ring, but occurs more at its anterior and posterior portions. As these outgrowths meet, they create a foramen in the floor of the meatus, the foramen of Huschke. This foramen is usually closed about the fifth year, but may persist throughout life.

- The mandibular fossa is at first extremely shallow, and looks lateral and inferior; it deepens and directs more inferiorly over time. The part of the squama which forms the fossa lies at first below the level of the zygomatic process. As, the base of the skull thickens, this part of the squama is directed horizontal and inwards to contribute to the middle cranial fossa, and its surfaces look upward and downward; the attached portion of the zygomatic process everts and projects like a shelf at a right angle to the squama.

- The mastoid portion is at first flat, with the stylomastoid foramen and rudimentary styloid immediately behind the tympanic ring. With air cell development, the outer part of the mastoid component grows anteroinferiorly to form the mastoid process, with the styloid and stylomastoid foramen now on the under surface. The descent of the foramen is accompanied by a requisite lengthening of the facial canal.

- The downward and forward growth of the mastoid process also pushes forward the tympanic part; as a result, its portion that formed the original floor of the meatus, and contained the foramen of Huschke, rotates to become the anterior wall.

- The subarcuate fossa is nearly effaced.

-

1. Outer surface of petromastoid part. 2. Outer surface of tympanic ring. 3. Inner surface of squama.

-

Temporal bone at birth. Outer aspect.

-

Temporal bone at birth. Inner aspect.

Clinical significance

[edit]Glomus jugulare tumor:

- A glomus jugulare tumor is a tumor of the part of the temporal bone in the skull that involves the middle and inner ear structures. This tumor can affect the ear, upper neck, base of the skull, and the surrounding blood vessels and nerves.

- A glomus jugulare tumor grows in the temporal bone of the skull, in an area called the jugular foramen. The jugular foramen is also where the jugular vein and several important nerves exit the skull.

- This area contains nerve fibers, called glomus bodies. Normally, these nerves respond to changes in body temperature or blood pressure.

- These tumors most often occur later in life, around age 60 or 70, but they can appear at any age. The cause of a glomus jugulare tumor is unknown. In most cases, there are no known risk factors. Glomus tumors have been associated with changes (mutations) in a gene responsible for the enzyme succinate dehydrogenase (SDHD).[4][5]

Trauma

[edit]Temporal bone fractures were historically divided into three main categories, longitudinal, in which the vertical axis of the fracture paralleled the petrous ridge, horizontal, in which the axis of the fracture was perpendicular to the petrous ridge, and oblique, a mixed type with both longitudinal and horizontal components. Horizontal fractures were thought to be associated with injuries to the facial nerve, and longitudinal with injuries to the middle ear ossicles.[6] More recently, delineation based on disruption of the otic capsule has been found as more reliable in predicting complications such as facial nerve injury, sensorineural hearing loss, intracerebral hemorrhage, and cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea.[7]

Other animals

[edit]In many animals some of these parts stay separate through life:

- Squamosal: the squama including the zygomatic process

- Tympanic bone: the tympanic part: this is derived from the angular bone of the reptilian lower jaw

- Periotic bone: the petrous and mastoid parts

- Two parts of the hyoid arch: the styloid process. In the dog these small bones are called tympanohyal (upper) and stylohyal (lower).

In evolutionary terms, the temporal bone is derived from the fusion of many bones that are often separate in non-human mammals:

- The squamosal bone, which is homologous with the squama, and forms the side of the cranium in many bony fish and tetrapods. Primitively, it is a flattened plate-like bone, but in many animals it is narrower in form, for example, where it forms the boundary between the two temporal fenestrae of diapsid reptiles.[8]

- The petrous and mastoid parts of the temporal bone, which derive from the periotic bone, formed from the fusion of a number of bones surrounding the ear of reptiles. The delicate structure of the middle ear, unique to mammals, is generally not protected in marsupials, but in placentals, it is usually enclosed within a bony sheath called the auditory bulla. In many mammals this is a separate tympanic bone derived from the angular bone of the reptilian lower jaw, and, in some cases, it has an additional entotympanic bone. The auditory bulla is homologous with the tympanic part of the temporal bone.[8]

- Two parts of the hyoid arch: the styloid process. In the dog the styloid process is represented by a series of four articulating bones, from top down tympanohyal, stylohyal, epihyal, ceratohyal; the first two represent the styloid process, and the ceratohyal represents the anterior horns of the hyoid bone and articulates with the basihyal which represents the body of the hyoid bone.

Etymology

[edit]Its exact etymology is unknown.[9] It is thought to be from the Old French temporal meaning "earthly", which is directly from the Latin tempus meaning "time, proper time or season." Temporal bones are situated on the sides of the skull, where grey hairs usually appear early on. Or it may relate to the pulsations of the underlying superficial temporal artery, marking the time we have left here. There is also a probable connection with the Greek verb temnion, to wound in battle. The skull is thin in this area and presents a vulnerable area for a blow from a battle axe.[10] Another possible etymology is described at Temple (anatomy).

Additional images

[edit]-

Position of temporal bone (green). Animation.

-

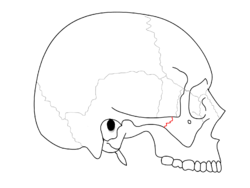

Shape of temporal bone (left)

-

Cranial bones

-

Sphenoid and temporal bones

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 138 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 138 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ "SKULL ANATOMY - TEMPORAL BONE". 28 June 2017.

- ^ Temporal bone anatomy on CT 2012-12-22

- ^ Chaurasia, BD (31 January 2013). Human Anatomy Volume 3 (Sixth ed.). CBS Publishers and Distributors Pvt Ltd. pp. 41–43. ISBN 9788123923321.

- ^ "Glomus jugulare tumor: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- ^ Sanei Taheri, Morteza; Zare Mehrjardi, Mohammad (2016-07-21). "Imaging of temporal bone lesions: developmental and inflammatory conditions".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Brodie, HA; Thompson, TC (March 1997). "Management of complications from 820 temporal bone fractures". The American Journal of Otology. 18 (2): 188–97. PMID 9093676.

- ^ Little, SC; Kesser, BW (December 2006). "Radiographic classification of temporal bone fractures: clinical predictability using a new system". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 132 (12): 1300–4. doi:10.1001/archotol.132.12.1300. PMID 17178939.

- ^ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Colorado, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. XXX. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ "Temporal | Search Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ^ "Etymology of Head Terms". www.dartmouth.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09.

External links

[edit]- "Anatomy diagram: 34256.000-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27.

Temporal bone

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Parts and components

The temporal bone is composed of four primary parts: the squamous part (squama), the tympanic part, the petrous part, and the mastoid part. The styloid process is a slender projection arising from the inferior surface between the mastoid and tympanic parts.[2][3] The squamous part, also known as the squama temporalis, is a thin, flat, scale-like plate that forms the superior and lateral aspect of the temporal bone, contributing to the floor of the temporal fossa. Its outer surface is smooth and convex, while the inner surface is concave and bears impressions for the temporal lobe of the cerebrum. The average thickness of the squamous part measures approximately 2.11 mm, varying slightly with age and sex.[3][4] The petrous part is a dense, pyramid-shaped structure wedged between the sphenoid and occipital bones at the base of the skull, representing the most medial and robust component of the temporal bone. It points anteromedially with its apex near the foramen lacerum and base fusing with the squamous and mastoid parts. Extending inferiorly and posteriorly from the base of the petrous part is the mastoid part, which features the mastoid process, a conical projection posterior to the external auditory meatus that contains a system of interconnected air cells (mastoid air cell system) within its porous interior. The mastoid process typically measures up to 34 mm in anteroposterior thickness in adults.[5][6][7] The tympanic part consists of a curved, plate-like bone that forms the anterior and inferior walls of the external auditory canal, located inferior to the squamous part and anterior to the mastoid process. It features a C-shaped configuration with a posterior projection that partially encloses the canal opening.[2][3] The styloid process is a slender, pointed projection arising from the inferior surface of the temporal bone, between the mastoid and tympanic parts, serving as an attachment site for muscles and ligaments. It has an average length of 2.5 cm and is often enclosed proximally by a thin plate of the tympanic part known as the vaginal process.[3][8] In adults, these parts are interconnected through ossified sutures that fuse during postnatal growth, obliterating the embryonic boundaries. The petrosquamous suture marks the junction between the petrous and squamous parts, forming a thin bony septum (Körner's septum) that separates the mastoid air cells from the middle cranial fossa. The petrotympanic suture unites the petrous and tympanic parts, transmitting the anterior tympanic branch of the maxillary artery and chorda tympani nerve. These fusions create a unified, irregular structure essential to the temporal bone's integrity.[9][10]Surfaces and borders

The external surface of the temporal bone is divided into three primary regions: the squamous, mastoid, and tympanic. The squamous region consists of a thin, flat, and slightly convex plate that forms the lateral wall of the skull and contributes to the floor of the temporal fossa.[2][3] The mastoid region, located posteriorly, features the mastoid process as a prominent projection that houses mastoid air cells.[2][3] Anteriorly, the tympanic region forms the bony portion of the external acoustic meatus, providing structural support for the external ear canal.[2][3] The internal surface, facing the cranial cavity and known as the cerebral surface, is characterized by the petrous ridge—a sharp, pyramid-shaped elevation that separates the middle cranial fossa anteriorly from the posterior cranial fossa posteriorly.[3] This surface bears various impressions and grooves, including those for the dura mater of the temporal lobe and the sigmoid sinus, facilitating the accommodation of intracranial structures.[3][1] The temporal bone's borders define its articulations with adjacent cranial bones. The superior border, primarily along the squamous part, articulates with the parietal bone to form the squamous suture.[2][3] The anterior border connects with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, establishing the sphenosquamous suture.[2][3] Posteriorly, the border articulates with the occipital bone via the lambdoid suture's extension, known as the occipitomastoid suture.[3] The inferior border, irregular and notched, includes the jugular notch where it meets the jugular process of the occipital bone to form the jugular foramen.[2][3] Notable features on the external surface include the zygomatic process, which extends anteriorly from the inferior aspect of the squamous part to articulate with the zygomatic bone, forming the zygomatic arch.[2][3] Adjacent to this, the mandibular fossa—a concave depression on the squama—serves as the site for articulation with the mandible in the temporomandibular joint.[2][3]Foramina, fissures, and canals

The temporal bone features numerous foramina, fissures, and canals that serve as passages for neurovascular structures, particularly those related to audition and cranial nerve transmission. These openings are distributed across its various parts, including the petrous, tympanic, and mastoid portions, facilitating connections between the cranial cavity, middle ear, and external regions. Key examples include the external acoustic meatus in the tympanic part, which forms the entrance to the external auditory canal for sound transmission to the eardrum.[11] Prominent foramina include the internal acoustic meatus, situated on the posterior surface of the petrous part, which transmits the facial nerve (CN VII), vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII), vestibular ganglion, and labyrinthine artery from the posterior cranial fossa to the inner ear.[12] The jugular foramen, formed at the junction of the petrous temporal bone and occipital bone, is divided into compartments that convey the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), vagus nerve (CN X), accessory nerve (CN XI), inferior petrosal sinus, and the origin of the internal jugular vein from the sigmoid sinus.[13] The stylomastoid foramen, located between the styloid and mastoid processes in the petromastoid region, provides the exit for the extracranial facial nerve and stylomastoid artery.[3] Fissures in the temporal bone primarily represent developmental suture lines or communication pathways. The petrotympanic fissure (Glaserian fissure), between the petrous and tympanic parts, connects the middle ear cavity to the infratemporal fossa and transmits the chorda tympani nerve, a branch of the facial nerve.[11] The petrosquamous fissure, separating the petrous and squamous parts, marks the site of early ossification fusion and typically transmits no major structures in the adult bone, though it may contain minor venous connections during development.[14] Significant canals include the carotid canal in the petrous part, which enters the inferior surface of the temporal bone and courses superiorly and anteriorly, bifurcating into a vertical petrous segment and a horizontal tympanic segment before opening into the middle cranial fossa to transmit the internal carotid artery.[12] The facial canal, originating within the petrous part and extending through the tympanic and mastoid parts, encases the facial nerve along its labyrinthine, tympanic, and mastoid segments, terminating at the stylomastoid foramen.[3] Additionally, the vestibular aqueduct, a narrow bony channel in the petrous part, extends from the vestibule of the inner ear to the posterior surface of the temporal bone, draining endolymph via the endolymphatic duct.[15]Development and growth

Embryonic development

The temporal bone originates primarily from the first and second pharyngeal arches, with additional contributions from the otic capsule derived from periotic mesenchyme, including mesoderm and neural crest cells, surrounding the developing inner ear. Neural crest cells contribute to structures such as the superstructure of the stapes and parts of the otic capsule. The first pharyngeal arch gives rise to the tympanic ring and the handle of the malleus, while the second pharyngeal arch contributes to the stapes, styloid process, and lesser horn of the hyoid bone.[16][17][18] Embryonic development of the temporal bone begins around weeks 4 to 5 of gestation, when the otic placode induces the formation of petrous precursors from surrounding mesenchyme. The otic placode, appearing in week 4, invaginates to form the otic vesicle, which differentiates into the membranous labyrinth by week 8, establishing the foundational sensory structures encased by the future otic capsule.[16][19] Key early structures include Reichert's cartilage, which arises from the second pharyngeal arch and forms the styloid process, parts of the malleus and stapes, and the lesser horn of the hyoid; the tympanic ring develops separately from the first arch as a C-shaped cartilage that later ossifies.[17][18] Genetic regulation involves Hox genes, which specify pharyngeal arch identity and organogenesis, such as Hoxa3 in patterning the third arch derivatives, and BMP signaling pathways, including BMP2a and BMP5, which promote mesodermal specification and arch artery formation through the BMP/Smad cascade.[20][21][22]Ossification and postnatal development

The temporal bone forms through a complex process involving multiple ossification centers, with three primary ones contributing to its major components. The squamous part ossifies via intramembranous ossification, beginning at a single center around the 8th gestational week in the region of the future zygomatic process.[23] The petromastoid part, encompassing the petrous pyramid and mastoid process, undergoes endochondral ossification starting around the 16th gestational week from approximately 20 separate centers within the cartilaginous otic capsule.[24] The tympanic part develops from an intramembranous ossification center at the 12th gestational week, forming the tympanic ring around the external auditory meatus.[24] Fusion of these components occurs progressively during childhood. The petrosquamous suture, separating the petrous and squamous parts, typically obliterates in adulthood.[25] The petrotympanic fissure, connecting the tympanic cavity to the infratemporal fossa, undergoes partial ossification in adulthood, reducing its patency while allowing passage of structures like the chorda tympani nerve.[26] Postnatally, the temporal bone undergoes significant remodeling and expansion. The mastoid air cell system, which provides structural support and aids in pressure equalization, begins developing shortly after birth through mucosal invaginations from the epitympanum into the mastoid process; the antrum is present at birth, but cellular pneumatization accelerates between birth and 2-3 years, with cells forming via epithelial outgrowths.[27] This process continues, reaching near-adult volume by puberty around 15-18 years.[28] Concurrently, the squamous part expands laterally with overall calvarial growth, contributing to the broadening of the cranial vault.[23] Several factors influence mastoid pneumatization during postnatal development. Hormonal influences, including growth hormone, play a role in overall craniofacial bone remodeling and may support the expansion of air cell volume.[29] Mechanical stimuli from activities such as sucking in infancy and mastication during childhood provide functional loading that promotes bone apposition and pneumatization progression, as seen in comparative studies of masticatory function and temporal bone morphology.[30] Genetic predisposition and avoidance of early infections also contribute to optimal development, with chronic otitis media potentially arresting cell formation.[31]Functions

Role in audition

The temporal bone plays a central role in audition by providing structural support for the external, middle, and inner ear components essential for sound transmission. The tympanic part of the temporal bone forms the medial two-thirds of the external auditory canal, a bony conduit that channels sound waves from the outer environment to the tympanic membrane, initiating the vibratory process of hearing.[32] Within the middle ear cavity, the petrous part houses the auditory ossicles—malleus, incus, and stapes—which amplify and transmit mechanical vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the inner ear, optimizing sound conduction efficiency.[1][33] The petrous portion of the temporal bone encases the cochlea and associated structures of the inner ear, creating a protective bony labyrinth that facilitates the conversion of sound vibrations into neural signals. Specifically, the cochlea, embedded within this dense pyramid-shaped bone, receives vibrations via the oval window, where the stapes footplate connects the middle ear to the scala vestibuli filled with perilymph; these vibrations propagate as fluid waves through the cochlear duct to the round window, which allows pressure release and ensures efficient sound transduction.[32][33] The round window, covered by a thin membrane, completes the hydraulic system by permitting perilymph movement, thereby preventing energy dissipation and supporting frequency-specific hair cell stimulation in the organ of Corti.[1] Although the petrous bone also encloses the semicircular ducts, their primary involvement in audition is indirect through shared perilymphatic pathways.[32] The dense composition of the petrous temporal bone contributes to acoustic isolation by dampening extraneous vibrations and minimizing sound leakage to surrounding cranial structures, thus preserving the fidelity of auditory signals directed to the brain.[33] This protective density shields the delicate cochlear apparatus from external noise interference, enhancing overall hearing sensitivity.[1] Key anatomical features include the tegmen tympani, a thin bony roof overlying the middle ear cavity that separates it from the middle cranial fossa while supporting ossicular stability during vibration transmission, and the promontory, a rounded projection in the medial wall of the middle ear formed by the basal turn of the cochlea, which influences the acoustic resonance within the tympanic cavity.[32][1] The internal acoustic meatus, traversing the petrous bone, provides passage for the auditory nerve, linking peripheral sound processing to central neural pathways.[33]Role in balance and equilibrium

The petrous part of the temporal bone encases the vestibular apparatus, providing rigid protection for the structures responsible for detecting head movements and maintaining equilibrium. This bony housing includes the bony labyrinth, a series of interconnected cavities filled with perilymph that surround the membranous labyrinth containing endolymph. The vestibular apparatus comprises the three semicircular canals—superior, posterior, and lateral—along with the utricle and saccule. The semicircular canals, oriented approximately orthogonally due to the pyramid-shaped configuration of the petrous temporal bone, detect angular accelerations of the head in three-dimensional space by sensing the deflection of endolymph within their ampullae.[1][34][35] The utricle and saccule, located within the vestibule of the bony labyrinth, function as otolith organs that sense linear accelerations and gravitational forces. These structures feature maculae with hair cells embedded in a gelatinous matrix containing otoconia, which shift in response to linear motion, stimulating sensory transduction for static and dynamic balance. The endolymphatic system supports this sensory function by maintaining the ionic composition of endolymph, a potassium-rich fluid essential for hair cell depolarization. The vestibular aqueduct, a narrow bony canal in the petrous temporal bone, drains excess endolymph from the endolymphatic sac to regulate fluid volume and pressure, thereby preserving homeostasis within the vestibular apparatus.[34][35][1] Neural signals from the vestibular apparatus are transmitted via the vestibular division of the vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII), which originates from the vestibular ganglion (Scarpa's ganglion) located in the internal acoustic meatus of the temporal bone. This meatus serves as a conduit for the nerve fibers to exit the petrous part and reach the brainstem, where they integrate with other sensory inputs for reflexive control of posture and eye movements. The precise anatomical positioning of the internal acoustic meatus within the temporal bone ensures efficient and protected conveyance of these balance-related signals.[1][35][34]Articulations and muscular attachments

The temporal bone forms several key articulations with adjacent cranial bones, primarily through fibrous sutures and one notable synovial joint. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a ginglymoarthrodial synovial joint located in the mandibular fossa, formed by the articulation between the condylar process of the mandible and the glenoid fossa of the squamous portion of the temporal bone.[36] This joint includes an articular disc that divides the joint cavity into superior and inferior compartments, along with a fibrous capsule reinforced by lateral and sphenomandibular ligaments.[36] Sutural articulations connect the temporal bone to surrounding skull elements via immovable fibrous joints. The squamosal suture joins the superior border of the squamous part of the temporal bone to the inferior border of the parietal bone.[37] The sphenosquamosal suture links the inferior border of the squamous part to the greater wing of the sphenoid bone.[37] Posteriorly, the parietomastoid suture unites the mastoid part of the temporal bone with the parietal bone, while the occipitomastoid suture connects the mastoid part to the occipital bone.[38] The temporal bone provides attachment sites for several muscles involved in head and neck movements. On the squamous part, the temporalis muscle originates from the temporal fossa and fascia covering the lateral surface.[39] The mastoid process serves as the insertion point for the sternocleidomastoid and posterior belly of the digastric muscles.[40] The styloid process, projecting from the temporal bone's base, gives origin to the stylohyoid and styloglossus muscles.[41] Ligamentous attachments further stabilize structures around the temporal bone. The stylohyoid ligament extends from the styloid process to the lesser horn of the hyoid bone and represents an ossified remnant of Reichert's cartilage from the second pharyngeal arch.[42] Additionally, extrinsic ligaments of the auricle, including the anterior and superior auricular ligaments, attach to the tympanic part of the temporal bone, anchoring the external ear to the skull.[43]Clinical significance

Trauma and fractures

Temporal bone fractures represent a significant component of skull base injuries, occurring in approximately 20-40% of such cases.[44] These fractures typically arise from high-energy blunt trauma, with motor vehicle accidents accounting for over 50% of adult cases and being the most common cause in children (47%), followed by falls (40%).[45][46] Assaults and other accidents contribute to the remainder, often resulting in unilateral involvement in about 83% of instances.[45] Notably, 70-80% of temporal bone fractures involve the petrous ridge, the dense portion of the bone housing critical auditory and vestibular structures.[45] Fractures are classified into two main types based on their orientation relative to the petrous axis: longitudinal and transverse. Longitudinal fractures, comprising 70-90% of cases, extend along the external auditory canal and petrous ridge, usually from lateral temporal impacts, and frequently spare the otic capsule while affecting the middle ear.[45][47] Transverse fractures, which are less common at 10-30%, propagate perpendicular to the petrous bone, often from occipital or frontal blows, and carry a higher risk of inner ear and cranial nerve damage due to their path through the otic capsule.[45][47] Associated injuries are common and can profoundly impact auditory and neurological function. Conductive hearing loss occurs in up to 66% of cases due to ossicular chain disruption from longitudinal fractures.[45] Sensorineural hearing loss affects about 5% overall but rises significantly with transverse fractures involving cochlear concussion.[45] Facial nerve palsy manifests in 7-12% of fractures, increasing to 48% when the otic capsule is involved, often due to breach of the facial canal.[45] Cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea is a frequent complication, particularly with fractures breaching the tegmen tympani or involving the internal acoustic meatus.[45]Infections and pathologies

The temporal bone is susceptible to various infectious and inflammatory pathologies, primarily arising from extensions of middle ear infections. Acute otitis media (AOM), a common bacterial infection in children, can progress to chronic suppurative otitis media if unresolved, leading to intratemporal complications such as mastoiditis and cholesteatoma.[48] Mastoiditis manifests as suppurative inflammation of the mastoid air cells within the temporal bone, often resulting in coalescent abscess formation due to pus accumulation and bone erosion in poorly pneumatized regions.[49] This condition disrupts the normal aeration of mastoid cells, which develop postnatally, exacerbating local spread.[49] Cholesteatoma represents another critical complication, characterized by the pathologic ingrowth of keratinizing squamous epithelium into the middle ear cleft, driven by tympanic membrane retraction or epithelial migration.[50] This leads to progressive bone resorption in the temporal bone through pressure necrosis and inflammatory mediators, potentially eroding structures like the ossicles or scutum.[51] Acquired cholesteatomas, the most prevalent type, often stem from repeated AOM episodes, while congenital variants arise from trapped epithelial rests during embryogenesis.[50] Osteomyelitis of the temporal bone, a more severe infectious process, involves bacterial invasion of the bone matrix, frequently complicating untreated otitis media or externa.[52] Petrous apicitis, an osteomyelitic focus at the petrous apex, can produce Gradenigo's syndrome, a classic triad of persistent otitis media, deep retro-orbital pain from trigeminal nerve irritation, and ipsilateral abducens nerve (CN VI) palsy due to inflammation in Dorello's canal.[53] This pathology arises from contiguous spread along vascular channels or air cell tracts, highlighting the temporal bone's interconnected anatomy.[54] Congenital anomalies of the temporal bone contribute to pathologic vulnerabilities by altering normal drainage and aeration pathways. External auditory canal atresia, a developmental malformation ranging from stenosis to complete absence, impairs sound conduction and predisposes to recurrent infections due to hypoplastic middle ear structures.[55] Similarly, persistence of the petrosquamous suture—manifesting as Körner's septum—divides the mastoid air cell system, potentially hindering pneumatization and facilitating infection trapping in superficial compartments.[56] Key risk factors for these temporal bone pathologies include eustachian tube dysfunction, which impairs middle ear ventilation and clearance, and immune compromise from conditions like diabetes or HIV.[48] Epidemiologically, AOM and its complications peak in pediatric populations aged 6-24 months, coinciding with immune maturation and exposure to respiratory pathogens in daycare settings.[48] Infection spread may occur via foramina such as the jugular, linking the temporal bone to deeper spaces.[57]Tumors and neoplasms

Tumors and neoplasms of the temporal bone encompass a range of benign and malignant growths that arise within or invade this complex structure, often presenting diagnostic challenges due to their proximity to critical neurovascular elements. These lesions are rare overall, with malignant tumors accounting for approximately 0.2% of all head and neck malignancies and an incidence of about 1 case per million population annually for cancers of the ear canal or middle ear. Benign neoplasms, while more common than their malignant counterparts, still represent a small fraction of intracranial tumors, with vestibular schwannomas alone having an estimated annual incidence of 1-2 per 100,000 individuals. Risk factors are limited but include prior ionizing radiation exposure to the head, which has been linked to an increased incidence of vestibular schwannomas. Benign tumors of the temporal bone include vestibular schwannoma, also known as acoustic neuroma, which originates from Schwann cells of the vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII) within the internal auditory meatus. This slow-growing, encapsulated lesion typically presents with gradual enlargement, leading to compression of adjacent neural structures. Glomus jugulare tumors, or jugular paragangliomas, are neuroendocrine neoplasms arising from paraganglionic tissue at the jugular foramen, often exhibiting vascularity and potential for local extension without distant metastasis. Another erosive benign growth is cholesteatoma, a non-neoplastic accumulation of keratinizing squamous epithelium in the middle ear or mastoid that expands destructively, eroding temporal bone and nearby ossicles through pressure and enzymatic activity. Malignant neoplasms primarily involve squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), the most common primary malignancy of the temporal bone, often originating from the external auditory canal, middle ear mucosa, or adjacent skin. This aggressive tumor accounts for 60-80% of temporal bone malignancies and tends to invade locally with a propensity for lymphatic spread to cervical nodes.[58] Temporal bone metastases are infrequent secondary lesions, typically from primaries such as breast, lung, or renal carcinomas, which seed hematogenously and cause osteolytic destruction within the bone. Staging of temporal bone tumors, particularly SCC, relies on systems like the modified University of Pittsburgh or Moody classification, which assess tumor extent based on involvement of the external auditory canal, middle ear, mastoid, petrous apex, and surrounding structures such as the facial nerve or dura. Tumors frequently spread via natural fissures and dehiscences, including the facial canal or petrotympanic fissure, allowing progression to the petrous apex and intracranial spaces. Common symptoms include progressive hearing loss, tinnitus, and facial nerve weakness due to compression or invasion, alongside otalgia and otorrhea in more advanced cases.| Tumor Type | Origin | Key Features | Common Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vestibular Schwannoma (Benign) | Schwann cells of CN VIII in internal auditory meatus | Slow-growing, encapsulated; may erode canal walls | Unilateral hearing loss, tinnitus, balance issues |

| Glomus Jugulare (Benign) | Paraganglionic tissue at jugular foramen | Vascular, locally invasive but non-metastasizing | Pulsatile tinnitus, hearing loss, cranial nerve palsies |

| Cholesteatoma (Benign, erosive) | Keratinizing epithelium in middle ear/mastoid | Expansive cyst-like growth causing bone erosion | Recurrent infections, conductive hearing loss, vertigo |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Malignant) | External/middle ear or skin | Aggressive local invasion, lymphatic spread | Otalgia, otorrhea, facial weakness |

| Temporal Bone Metastases (Malignant) | Hematogenous from distant primaries (e.g., breast, lung) | Osteolytic, multifocal possible | Hearing loss, pain, cranial neuropathies |