Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Reassortment.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reassortment

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Reassortment

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

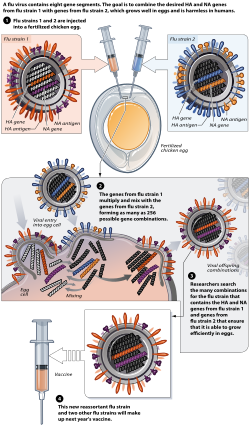

Reassortment is a form of genetic recombination unique to viruses with segmented RNA genomes, occurring when two or more distinct viral strains co-infect the same host cell and exchange entire genome segments during progeny virus assembly, resulting in novel hybrid viruses with mixed parental genetic material.[1][2]

This process is a key evolutionary mechanism in families such as Orthomyxoviridae (e.g., influenza viruses with 6–8 segments) and Reoviridae (e.g., rotaviruses with 10–12 segments), enabling rapid generation of genetic diversity far beyond what point mutations alone can achieve.[2] The mechanism relies on compatible packaging signals and protein-RNA interactions that allow selective or random incorporation of segments from different parental viruses into new virions, often during high-multiplicity infections in natural reservoirs like aquatic birds for influenza.[1][2]

Reassortment plays a critical role in viral adaptation, interspecies transmission, and the emergence of pandemics by conferring fitness advantages such as enhanced host range, immune evasion, or drug resistance, as seen in the 1957 H2N2, 1968 H3N2, and 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemics, which arose from reassortment events involving human, avian, and swine strains.[1][2] It also contributes to antigenic shift in influenza, complicating vaccine development, though it has been harnessed positively in live-attenuated vaccines like FluMist for influenza and RotaTeq for rotavirus.[2] While reassortment can sometimes produce less fit or non-viable progeny due to genetic incompatibilities, its frequency in natural settings—up to 25% mixed infections in wild birds—underscores its significance in driving long-term viral evolution and zoonotic potential.[1][2]

Overview

Definition

Reassortment is a genetic process in which two different strains of a virus with a segmented genome exchange entire genome segments, producing progeny viruses that possess novel combinations of these segments.[3] This mechanism allows for rapid genetic diversification without the need for mutations within individual segments.[2] Unlike recombination, which entails the breakage and rejoining of nucleic acid strands to create hybrid sequences, reassortment specifically involves the redistribution of pre-existing, intact genome segments between co-infecting viral strains, preserving the original sequence of each segment.[4] Recombination can occur in non-segmented viruses through template switching or other molecular events, but reassortment is exclusive to those with multipartite genomes.[5] For reassortment to occur, a single host cell must be co-infected by at least two distinct viral strains, enabling the mixing of their genome segments during viral replication and packaging.[6] This process is restricted to viruses featuring segmented genomes, predominantly RNA viruses with 2 to 12 discrete segments, exemplified by the influenza A virus and its eight RNA segments.[7]Mechanism in Segmented Viruses

Reassortment in segmented viruses occurs through a series of cellular events that enable the exchange of entire genome segments between co-infecting viral strains, generating progeny virions with hybrid genomes. This process is characteristic of viruses with multipartite genomes, such as those in the families Orthomyxoviridae, Reoviridae, and Bunyaviridae, where the genome consists of multiple discrete RNA segments. The mechanism relies on the independent handling of these segments during the viral life cycle, allowing for genetic mixing without the need for breakage and rejoining of nucleic acids, unlike classical recombination.[2][8] The process begins with co-infection of a host cell by two or more distinct viral strains, where each virion enters the cell and releases its genome segments into the appropriate cellular compartment—typically the cytoplasm for most segmented RNA viruses, or the nucleus for orthomyxoviruses like influenza. Upon entry, the viral ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) dissociate, freeing the individual RNA segments for subsequent processing. This simultaneous presence of segments from different parental strains sets the stage for potential mixing, with the likelihood of co-infection increasing at higher multiplicities of infection (MOI), such as when multiple virions infect the same cell.[2][9][8] Following release, the individual genome segments undergo transcription and replication independently, without physical linkage between them. Viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps), often associated with host or viral proteins, recognize specific promoter sequences on each segment to initiate synthesis of mRNA and full-length antigenomic copies. For instance, in segmented negative-sense RNA viruses, the polymerase complex transcribes each segment separately within the RNP structure, while in double-stranded RNA viruses, viral polymerases within subviral particles transcribe the dsRNA segments to produce mRNA and synthesize new dsRNA segments through replication using plus-sense intermediates.[2][9][8][10] This autonomous replication of segments from both parental strains produces a pool of mixed nucleic acids in the infected cell, facilitating the potential for reassortment by decoupling segment production from parental origin.[2][9][8] During the final assembly phase, new virions form by packaging a complete set of genome segments into capsids or envelopes. Packaging is generally selective, guided by RNA-RNA or protein-RNA interactions at the segment termini, but when segments from multiple strains are present, random or semi-random assortment can occur, resulting in progeny that incorporate a mixture of segments from different parents. For example, in viruses with eight segments, such as orthomyxoviruses, co-infection can yield hybrid virions containing any combination, like four segments from strain A and four from strain B, as illustrated in conceptual diagrams of segment mixing. The efficiency of this step depends on compatibility between heterologous segments; incompatible combinations may reduce viability, but successful packaging produces infectious reassortants.[2][11][8] The probability of reassortment is influenced by several factors, including the number of genome segments—viruses with more segments (e.g., 10-12 in reoviruses) offer greater opportunities for mixing compared to those with fewer (e.g., 3 in cystoviruses)—and the MOI, where higher infection rates promote co-infection and thus elevate reassortment rates up to a plateau. Additionally, the specificity of viral polymerases in recognizing and replicating segments from different strains can modulate efficiency; high compatibility enhances independent assortment, while mismatches may limit it. These elements collectively determine the rate at which novel genomic combinations emerge, underscoring reassortment's role as a rapid evolutionary mechanism in segmented viruses.[2][9][8]Reassortment in Influenza

Genetic Structure Enabling Reassortment

The genome of influenza A virus consists of eight distinct segments of negative-sense, single-stranded RNA, totaling approximately 13.5 kilobases (kb) in length.[12][13] Each segment functions as an independent unit, encoding one or more viral proteins essential for replication and assembly; for instance, segment 1 encodes the PB2 subunit of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, while segment 7 encodes the M1 matrix protein and the M2 ion channel protein via alternative splicing.[12][14] This segmented architecture contrasts with unsegmented viral genomes and provides the structural basis for reassortment by allowing segments to be transcribed, replicated, and packaged separately without interdependency.[15] The linear, modular nature of these RNA segments enables efficient independent replication in the host cell nucleus, where each segment is transcribed into positive-sense mRNA and replicated into complementary RNA intermediates before being packaged into new virions.[12] During virion assembly, specific packaging signals at the ends of each segment ensure selective incorporation, but the lack of rigid linkage between segments permits random or selective mixing when multiple viral strains co-infect a cell.[16] This flexibility is particularly evident in segments 4 and 6, which encode the hemagglutinin (HA) surface glycoprotein and neuraminidase (NA) enzyme, respectively; reassortment of these segments generates novel HA and NA combinations that define influenza subtypes (e.g., H1N1 or H3N2) and drive antigenic diversity.[14][12] In comparison, non-segmented negative-sense RNA viruses, such as paramyxoviruses (e.g., measles or respiratory syncytial virus), possess a single continuous RNA genome molecule that precludes reassortment, limiting genetic exchange to rare recombination events rather than wholesale segment swapping.[17] The absence of segmentation in these viruses maintains greater genomic stability but restricts the rapid evolutionary adaptability observed in influenza.[18]Process During Co-Infection

Reassortment in influenza viruses typically initiates during co-infection of a host cell by two distinct strains, such as human and avian subtypes, often in intermediate hosts like pigs that express both α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialic acid receptors.[19] This dual infection allows the viruses to replicate concurrently, providing the opportunity for genetic segment exchange among the eight RNA segments of the influenza A genome.[20] In natural settings, such co-infections are relatively rare due to host barriers and low viral loads, but they can occur in the respiratory tract of mammals or birds, leading to the production of hybrid progeny viruses.[21] Upon entry into the host cell, the viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs)—each consisting of a viral RNA segment encapsidated by nucleoprotein (NP) and associated with the heterotrimeric RNA polymerase (PB2, PB1, PA)—are transported to the nucleus, where influenza A and B viruses uniquely replicate among RNA viruses.[19] In the nucleus, the incoming vRNPs from both co-infecting strains disassociate and undergo transcription via cap-snatching of host pre-mRNAs to produce viral mRNAs, followed by replication: primary synthesis of complementary RNA (cRNA) intermediates and secondary production of progeny vRNAs to form new vRNPs.[19] During this nuclear phase, vRNPs from the different parental strains mix freely in the nucleoplasm, enabling the exchange of entire genome segments without requiring recombination within segments.[20] Packaging of these mixed vRNPs into progeny virions occurs at the plasma membrane, guided primarily by random assortment but influenced by segment-specific packaging signals at the 5' and 3' non-coding regions, which ensure functional compatibility—such as matching polymerase subunits (PB2, PB1, PA) for efficient replication.[19] Evidence suggests some selectivity, as incompatible segment combinations may reduce viability, though most reassortants incorporate 0-100% segments from each parent, with 50:50 hybrids common in high co-infection scenarios.[22] The resulting progeny viruses thus exhibit diverse genotypes, propagating the reassortant strains upon release and spread.[20] The rate of reassortment is heavily influenced by factors like multiplicity of infection (MOI), with high MOI (e.g., 10 PFU/cell in vitro) yielding up to 88% reassortants due to frequent co-infection of cells, whereas natural infections involve lower viral doses and thus lower probabilities in animal models like pigs.[22] Timing of co-infection also matters; delays up to 8-12 hours between strains still permit robust mixing in vivo, reflecting the extended nuclear replication window.[22]Role in Antigenic Shift

Antigenic shift refers to an abrupt and major change in the hemagglutination inhibition (HA) and/or neuraminidase (NA) surface antigens of influenza A viruses, primarily driven by genetic reassortment of their segmented RNA genome during co-infection of a host cell by two distinct viral strains.[23] This process contrasts sharply with antigenic drift, which involves gradual, incremental mutations in the HA and NA genes that result in minor antigenic variations over time.[24] Reassortment enables the exchange of entire genome segments, particularly those encoding HA and NA, leading to novel combinations that can dramatically alter viral antigenicity.[25] The immunological impact of antigenic shift is profound, as the resulting novel HA and/or NA proteins often evade pre-existing immunity in human populations, allowing the reassortant virus to spread efficiently and potentially cause pandemics.[23] Unlike drift, which typically leads to seasonal epidemics in partially immune hosts, shift produces viruses to which most individuals have little or no immunity, facilitating rapid global transmission.[24] This immune escape is exemplified by the creation of new influenza subtypes designated by the HxNy nomenclature, where "H" and "N" denote the specific HA and NA types; for instance, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus arose from reassortment between North American swine, Eurasian swine, human, and avian influenza strains, yielding a previously unseen H1N1 combination.[23] Antigenic shift occurs infrequently in humans, with major events separated by decades—such as the pandemics of 1918 (H1N1), 1957 (H2N2), 1968 (H3N2), and 2009 (H1N1)—but is far more common in animal reservoirs like birds and pigs, where diverse strains co-circulate and facilitate frequent reassortment.[24] Genetic analyses of pandemic strains provide compelling evidence for this mechanism, revealing mosaic genomes with HA and NA segments originating from non-human sources; for example, phylogenetic analyses of the 1918 H1N1 virus suggest its unique gene constellation may have resulted from reassortment events, including avian-like HA contributions that enhanced human adaptation.[24] Such phylogenetic studies underscore reassortment's role in generating the antigenic novelty central to shift.[25]Historical and Recent Examples in Influenza

Past Pandemics

The 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic, caused by an H1N1 virus, has been the subject of debate regarding its origins, with genetic analyses suggesting it likely emerged from a direct avian source adapted to humans rather than through reassortment, though some studies propose a possible reassortment event between a preexisting human H1 lineage and an avian virus.[26][27] This event resulted in an estimated 50 million deaths worldwide, marking it as one of the deadliest pandemics in history, but its distinction from clear reassortment-driven shifts sets it apart from later 20th-century outbreaks.[26] The 1957 Asian influenza pandemic arose from an H2N2 virus generated by reassortment between the circulating human H1N1 virus and an avian H2N2 strain, incorporating three avian gene segments—hemagglutinin (HA) encoding H2, neuraminidase (NA) encoding N2, and polymerase basic 1 (PB1)—while retaining five internal segments from the human virus.[28][29] Genetic sequencing has traced these swaps, confirming the avian origins of the HA, NA, and PB1 genes through phylogenetic analysis of archived samples, which revealed distinct avian-like sequences in the pandemic strain not present in prior human viruses.[30] This reassortant virus spread rapidly from East Asia, causing an estimated 1 to 2 million deaths globally, with approximately 1.1 million excess deaths attributed to the pandemic based on epidemiological modeling.[31][32] In 1968, the Hong Kong influenza pandemic emerged from an H3N2 reassortant virus that acquired two avian gene segments—HA encoding H3 and PB1—from an avian source, integrating them into the backbone of the prevailing human H2N2 virus while keeping the N2 NA segment from the 1957 strain.[28][33] Genomic studies have verified this through sequence comparisons, showing the avian HA and PB1 formed a novel phylogenetic clade distinct from human lineages, enabling the antigenic shift that evaded population immunity.[30] Originating in southern China, the virus led to approximately 1 million deaths worldwide, with about 100,000 in the United States alone.[34][35] The 2009 swine-origin H1N1 pandemic stemmed from a quadruple reassortant virus, tracing back to a triple reassortant event in North American swine around 1998 that combined genes from classical swine H1N1, North American avian influenza, and human H3N2 viruses, followed by further reassortment with an Eurasian avian-like swine H1N1 lineage.[36] Full-genome sequencing of isolates confirmed this complex genealogy, with the pandemic strain featuring six segments from the 1998 triple reassortant swine virus and two from the Eurasian swine lineage, highlighting multiple interspecies jumps.[36] This virus caused an estimated 151,700 to 575,400 deaths globally in its first year, underscoring the role of swine as an intermediate host for such genetic exchanges.[37]Modern Surveillance and Emerging Strains

The World Health Organization's Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS), comprising over 140 national influenza centers worldwide, plays a central role in monitoring influenza viruses for reassortment events through routine genomic sequencing and epidemiological reporting.[38][39] This network analyzes thousands of samples annually to identify genetic signals of reassortment, particularly in zoonotic interfaces like avian-human mixes, with findings disseminated in WHO's annual influenza updates and risk assessments that highlight potential antigenic shifts.[38] For instance, GISRS tracks the circulation of avian influenza subtypes in poultry and wild birds, correlating them with human cases to flag interspecies transmission risks.[39] In the 2020s, notable reassortant strains have emerged, exemplified by highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, which has spilled over into mammals including dairy cattle during widespread outbreaks in the United States.[40] These viruses, identified as genotype B3.13, resulted from reassortment events incorporating PA, HA, NA, and M segments from Eurasian H5N1 lineages with other segments from North American low-pathogenic avian influenza strains, likely occurring in wild birds before transmission to cattle.[40] As of September 2025, over 1,700 dairy herds across 18 U.S. states have been affected, with approximately 70 linked human cases reported, primarily mild conjunctivitis and respiratory symptoms in farm workers, underscoring the pandemic potential if further mammalian adaptation occurs, such as PB2 E627K mutations enhancing human receptor binding.[40][41][42][43] Genomic surveillance has identified over 100 reassortant genotypes of H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b in North America since 2024, with ongoing detections in wild birds and mammals highlighting persistent reassortment risks.[44] Ongoing surveillance has also detected complex reassortants in swine populations, such as quadruple reassortant H1N2 variants incorporating genes from the 2009 pandemic H1N1 (PB2, PB1, PA, NP), triple-reassortant swine lineages (NS), and Eurasian avian-like H1N1 components, isolated in China as early as 2021 and persisting into the mid-2020s.[45] These strains, circulating in pig herds, pose risks for further reassortment with human or avian viruses due to swine's role as mixing vessels, with genomic analyses revealing stable Eurasian gene integrations that enhance transmissibility.[45][46] Advanced tools have bolstered detection efforts, including next-generation sequencing (NGS) protocols that enable whole-genome analysis for rapid segment origin tracing in reassortants, as implemented in GISRS laboratories to process samples within days.[47] Complementary predictive modeling, such as machine learning frameworks assessing genetic compatibility, forecasts reassortment risks by simulating segment pairings from surveillance data, aiding prioritization of high-threat combinations like H5N1 with human-adapted internal genes.[48][49] As of November 2025, post-COVID-19 enhancements to surveillance have intensified focus on interspecies jumps under a One Health approach, with no major human influenza pandemic reported but elevated alerts for HPAI H5N1 due to its panzootic spread in mammals and over 100 human cases globally since late 2024 (including more than 70 in the US), mostly occupational exposures.[50][51][52][53] Organizations like the CDC and WHO have expanded wastewater and serological monitoring in high-risk areas, emphasizing early detection to mitigate zoonotic threats informed by pandemic lessons.[52][54]Reassortment in Other Viruses

Arenaviruses

Arenaviruses possess a bisegmented, ambisense, single-stranded RNA genome consisting of a small (S) segment of approximately 3.5 kb and a large (L) segment of about 7.2 kb, totaling around 10.7 kb, which encodes four viral proteins: glycoprotein precursor (GPC) and nucleoprotein (NP) on the S segment, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) and matrix protein (Z) on the L segment.[55] This segmented structure facilitates reassortment when cells are co-infected by two different arenavirus strains, allowing the exchange of entire S or L segments to produce hybrid progeny viruses.[56] Reassortment has been demonstrated in arenaviruses such as Lassa virus (LASV), where hybrids between LASV and the closely related, non-pathogenic Mopeia virus (MOPV) have been generated in rodent models simulating natural reservoir conditions.[57] Similarly, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), the prototypic arenavirus, has produced lab-induced reassortants through dual infections in cell culture, revealing how segment exchange can alter viral tropism and pathogenicity in mouse models.[58] In natural settings, reassortment occurs frequently among arenaviruses within their rodent reservoir hosts, such as Mastomys natalensis for LASV, where co-infections in these multimammate rats lead to the emergence of novel pathogenic strains adapted to specific ecological niches.[59] This process contributes to the geographic diversity of arenavirus strains, exemplified by clade-specific LASV variants in West Africa, including lineages I-IV circulating in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea, which exhibit distinct phylogeographic patterns potentially driven by reassortment events.[60] Detection of reassortment in arenaviruses remains challenging in field studies due to sparse sampling of reservoir populations and the difficulty in identifying co-infections, resulting in limited direct evidence from natural sources; however, it has been robustly confirmed in cell culture systems using genetically marked viruses.[56]Bunyaviruses and Reoviruses

Bunyaviruses possess tri- or tetra-segmented genomes consisting of negative-sense single-stranded RNA, with the majority featuring three segments designated as small (S), medium (M), and large (L), which encode proteins essential for viral replication, glycoproteins, and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, respectively.[61] For instance, Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV), a prominent phlebovirus within the family, maintains a tri-segmented genome and undergoes reassortment in both mosquito vectors and mammalian hosts, as evidenced by genetic exchanges between strains from endemic regions in West and East Africa.[62] This process is facilitated by the virus's cytoplasmic replication, which allows for efficient segment shuffling during co-infection in arthropod vectors such as Aedes mosquitoes, where high-frequency reassortants have been observed following dual ingestion of related strains.[63] Such vector-mediated reassortment contributes to the emergence of variants with altered pathogenicity, often transmitted to livestock and humans in arid and semi-arid regions of Africa.[64] Notable examples include Schmallenberg virus, an orthobunyavirus that emerged in Europe in 2011, causing widespread veterinary outbreaks characterized by fever, diarrhea in adult ruminants, and congenital malformations in newborns; phylogenetic analyses reveal it as a natural reassortant, with its M segment derived from Sathuperi virus and S and L segments from Shamonda virus, highlighting reassortment's role in rapid viral evolution and epizootic spread via Culicoides midges.[65] A more recent example is the Oropouche virus (OROV), an orthobunyavirus, where a novel reassortant lineage has driven a major outbreak in the Americas from 2023 to 2025, affecting thousands in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, and other countries, with increased zoonotic transmission to humans causing febrile illness.[66] Similarly, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV), a nairovirus transmitted by Hyalomma ticks, exhibits segment reassortment leading to hybrid strains, such as those combining S and M segments from geographically distinct lineages in southern Africa, potentially enhancing virulence or host range in human and animal populations.[67] These arthropod-borne events underscore reassortment's contribution to bunyavirus diversity and the unpredictable nature of outbreaks in vector-endemic areas.[68] Reoviruses feature double-stranded RNA genomes organized into 10 to 12 segments, enabling high reassortment potential during co-infection; rotavirus A, the primary etiological agent of severe dehydrating gastroenteritis in young children worldwide, exemplifies this with its 11-segment genome, where segments encode structural proteins like VP4 (P genotype) and VP7 (G genotype), alongside non-structural factors.[69] Reassortment occurs frequently in the intestinal epithelial cells of infected children, driven by the virus's cytoplasmic replication in gut mucosa, which promotes random segment exchange and generates diverse progeny during mixed infections common in high-density settings like daycare centers.[70] This mechanism is particularly evident in the mixing of G and P genotypes, such as combinations of G1P[71] (Wa-like) and G2P[72] (DS-1-like) strains, resulting in intergenogroup reassortants that alter antigenicity and transmission dynamics.[73] Post-2006 introduction of oral rotavirus vaccines like Rotarix and RotaTeq, which target common G1P[71] and related strains, reassortment has driven the emergence of vaccine-escape variants, including G2P[72] and double-gene reassortants like DS-1-like G1P[71], observed in increased proportions among vaccinated children and linked to shifts in global genotype prevalence.[74] Recent surveillance as of 2025 has identified novel reassortants, such as equine-like G3P[71] strains in Benin, contributing to ongoing genotype shifts and potential reductions in vaccine effectiveness in post-vaccination settings in sub-Saharan Africa.[75] These events highlight reassortment's evolutionary pressure in pediatric populations, where ongoing surveillance is crucial to monitor gastrointestinal disease burdens and vaccine efficacy against evolving strains.[76]Additional Viral Families

Reassortment in orthobunyaviruses extends beyond primary bunyaviral examples to include La Crosse virus (LACV), where segment mixing occurs frequently in natural mosquito vectors such as Aedes triseriatus. Phylogenetic and linkage disequilibrium analyses of field-collected viruses from infected mosquitoes revealed that approximately 25% of samples contained reassorted genome segments, indicating that co-infection in the vector facilitates genetic exchange in nature.[77] This process is enhanced by vertical transmission in mosquitoes, increasing opportunities for reassortment during blood meals from viremic hosts.[77] Reptarenaviruses, members of the Arenaviridae family with bisegmented genomes, exhibit high rates of reassortment in captive snakes, contributing to the diversity of strains causing boid inclusion body disease (BIBD), particularly in boa constrictors (Boa constrictor). Genetic analyses of reptarenavirus infections in snakes have identified widespread reassortment alongside recombination, leading to novel genomic constellations that correlate with disease manifestations like inclusion bodies in neural tissues.[78] Experimental passaging in cultured snake cells further demonstrates restrictions in segment reassortment based on tissue tropism, suggesting host factors influence viable reassortant formation.[79] In boa constrictors, co-infections with multiple reptarenavirus strains often result in persistent infections and BIBD progression.[78] Hantaviruses, tri-segmented members of the Hantaviridae family, show rare but documented reassortment events primarily in rodent reservoirs, as seen in Seoul orthohantavirus (SEOV) variants. Evolutionary studies of SEOV genomes from Rattus norvegicus populations indicate infrequent inter-lineage reassortment, with the M segment commonly involved in exchanges that may enhance host adaptation without altering pathogenicity significantly.[80] Such events are detected through phylogenetic incongruence across segments, highlighting reassortment as a driver of genetic diversity in rodent-transmitted hantaviruses like SEOV.[81] Birnaviruses, double-stranded RNA viruses with two segments, undergo reassortment in poultry hosts, notably with infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), leading to emergent strains that impact vaccination efficacy. Natural reassortants of IBDV, such as those combining virulent and attenuated segment profiles, have been isolated from broiler flocks, demonstrating altered pathogenicity and immunosuppression in young chickens.[82] For instance, reassortant IBDV strains with a segment A from very virulent isolates and segment B from classical strains exhibit intermediate virulence, underscoring the role of reassortment in modulating disease severity.[83] In the 2020s, reports have emerged of reassortment in tick-borne segmented viruses resembling flaviviruses, particularly Jingmen tick virus (JMTV), a tetrasegmented pathogen detected in ticks and vertebrates. Genomic analyses of JMTV strains from China and Guinea revealed reassortment events, such as exchanges in segment 3, contributing to low genetic diversity and documented cross-species transmission, including human infections causing febrile illness in China as of 2025.[84][85] Phylogenetic studies confirm JMTV's capacity for reassortment, with strains showing mixed segment origins that may facilitate adaptation to new hosts like mammals.[86] This segmented structure bridges flavivirus-like features with reassortment potential, raising concerns for emerging tick-borne threats.[87]Implications and Applications

Evolutionary Impact

Reassortment significantly accelerates the generation of genetic diversity in segmented viruses by enabling the rapid production of chimeric genomes through the exchange of entire genome segments during co-infection, outpacing the slower process of point mutations and allowing viruses to more efficiently explore fitness landscapes.[88] This mechanism introduces novel genotypic combinations that can enhance viral adaptability, as observed in influenza A viruses where reassortment yields subpopulations with high genotypic richness (4–18 variants within hosts).[88] Unlike mutation-driven evolution, reassortment breaks linkage disequilibrium across segments, facilitating the simultaneous incorporation of multiple advantageous traits.[89] The adaptive advantages of reassortment stem from its ability to combine beneficial traits from parental viruses, such as expanded host range from one strain and increased virulence from another, thereby promoting host jumps and immune evasion.[1] For instance, in influenza A viruses, reassortment integrates avian-derived segments for enhanced human transmissibility with segments conferring higher pathogenicity, accelerating adaptation to new hosts faster than sequential mutations.[1] This combinatorial potential allows viruses to overcome host barriers and evade immunity, as evidenced by the emergence of pandemic strains through such genomic mixing.[1] However, reassortment faces intrinsic barriers related to segment compatibility, including RNA-based mismatches in packaging signals and protein-based incompatibilities, such as polymerase subunit mismatches that impair transcription and replication efficiency.[90] For example, mismatches between polymerase proteins like PB2 from one strain and PA from another (e.g., specific residues at PA positions 184 and 383) reduce viral viability by hindering genome assembly and progeny production, often necessitating compensatory mutations for fitness restoration.[90] These constraints limit the success rate of reassortant progeny, channeling evolutionary outcomes toward compatible segment combinations.[90] Over the long term, reassortment drives viral speciation by creating stable novel lineages with distinct properties, contributing to the evolution of quasispecies in natural reservoirs like avian hosts for influenza, where diverse segment pools sustain ongoing adaptation.[89] In these reservoirs, reassortment enriches quasispecies diversity, enabling viruses to persist asymptomatically and emerge with altered phenotypes, such as increased resistance or pathogenicity.[89] Mathematical models of reassortment, incorporating co-infection dynamics, estimate rates ranging from 10^{-6} to 10^{-3} per co-infection per day, highlighting its frequency as a key evolutionary driver under varying transmission and immunity pressures.[91]Challenges in Disease Prevention

Reassortment in influenza viruses poses significant hurdles to vaccine development and deployment, primarily because it drives antigenic shift, leading to novel strains that evade existing immunity. Seasonal influenza vaccines must be updated annually to match predicted circulating strains, a process complicated by the potential for reassortment events that introduce mismatched hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) segments from animal reservoirs, resulting in reduced vaccine efficacy during outbreaks.[92][23][93] To address this, efforts toward universal influenza vaccines focus on conserved internal viral proteins, such as the HA stalk domain, M2 ectodomain (M2e), and nucleoprotein (NP), which are less prone to reassortment-induced variation and can elicit broad cross-protective T-cell responses against diverse strains.[94][95][96] Antiviral therapies face similar challenges, as reassortment facilitates the rapid dissemination of resistance mutations across viral populations. For instance, the H275Y mutation in the NA gene, conferring resistance to oseltamivir, spread globally in seasonal H1N1 viruses from 2007 to 2009 through reassortment with susceptible strains, maintaining viral fitness and complicating treatment during the 2009 pandemic.[97][98][99] This mechanism allows resistance genes to transfer between subtypes, potentially amplifying the threat in mixed human-animal interfaces where co-infections occur.[100] Surveillance for reassortment events is hindered by the unpredictable nature of genetic mixing in animal reservoirs, such as poultry and swine, where viruses can silently evolve before spilling over to humans. Recent examples include the 2024–2025 highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) outbreaks in U.S. dairy cattle herds and reassortant variants like the EA-2023-DG clade in Europe, highlighting ongoing interspecies transmission risks and the need for enhanced monitoring.[101][102] Predicting these interspecies reassortants is difficult due to incomplete monitoring of wildlife and livestock, underscoring the need for One Health initiatives that integrate veterinary, human, and environmental data to bridge these gaps.[103][104][105] Emerging therapeutic strategies offer potential solutions, with mRNA vaccines providing flexibility to rapidly adapt to reassortant strains by encoding conserved antigens like internal proteins, enabling quicker production and broader protection compared to traditional platforms.[106][107] In contrast, live-attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIVs) carry risks of further reassortment with wild-type viruses in vaccinated hosts, potentially generating virulent progeny, though studies indicate such events are rare and often result in attenuated outcomes.[108][109][110] At the policy level, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes early detection of novel reassortants through its Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS), which coordinates international monitoring to inform pandemic preparedness and timely vaccine strain selection.[111][112][39] This framework supports proactive measures, such as enhanced genomic sequencing at human-animal interfaces, to mitigate the spread of reassortant threats before they escalate into pandemics.[113]References

- Jul 9, 2015 · Reassortment is an evolutionary mechanism of segmented RNA viruses that plays an important but ill-defined role in virus emergence and ...

- Reassortment is the mechanism of "genetic shift" whereby influenza viruses rapidly acquire new hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antigens. This is the initiating ...