Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart[1][2] and is an example of extensional tectonics.[3] Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben with normal faulting and rift-flank uplifts mainly on one side.[4] Where rifts remain above sea level they form a rift valley, which may be filled by water forming a rift lake. The axis of the rift area may contain volcanic rocks, and active volcanism is a part of many, but not all, active rift systems.

Major rifts occur along the central axis of most mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust and lithosphere is created along a divergent boundary between two tectonic plates.

Failed rifts are the result of continental rifting that failed to continue to the point of break-up. Typically the transition from rifting to spreading develops at a triple junction where three converging rifts meet over a hotspot. Two of these evolve to the point of seafloor spreading, while the third ultimately fails, becoming an aulacogen.

Geometry

[edit]

Most rifts consist of a series of separate segments that together form the linear zone characteristic of rifts. The individual rift segments have a dominantly half-graben geometry, controlled by a single basin-bounding fault. Segment lengths vary between rifts, depending on the elastic thickness of the lithosphere.

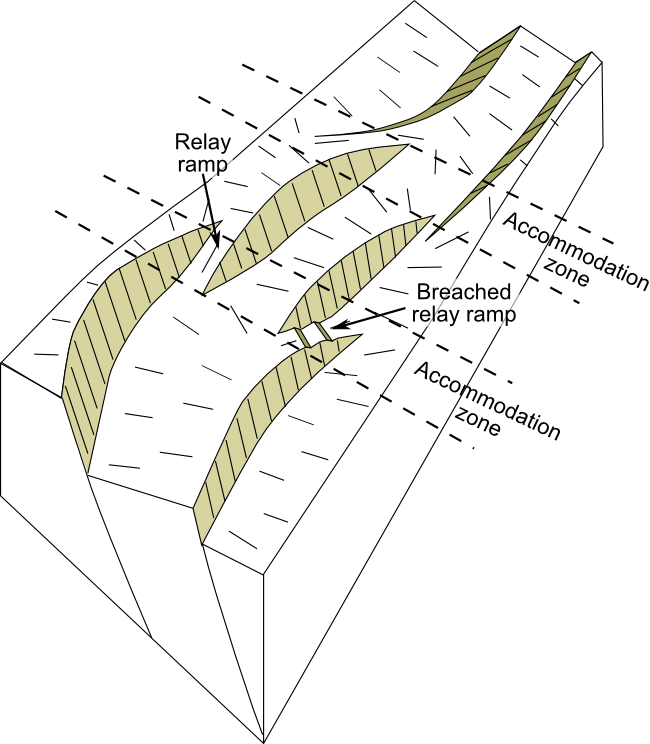

Areas of thick colder lithosphere, such as the Baikal Rift, have segment lengths in excess of 80 km, while in areas of warmer thin lithosphere, segment lengths may be less than 30 km.[5] Along the axis of the rift the position, and in some cases the polarity (the dip direction), of the main rift bounding fault changes from segment to segment. Segment boundaries often have a more complex structure and generally cross the rift axis at a high angle. These segment boundary zones accommodate the differences in fault displacement between the segments and are therefore known as accommodation zones.

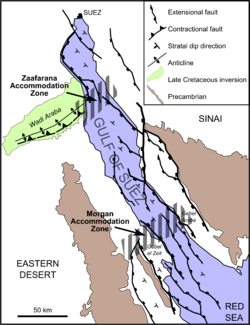

Accommodation zones take various forms, from a simple relay ramp at the overlap between two major faults of the same polarity, to zones of high structural complexity, particularly where the segments have opposite polarity. Accommodation zones may be located where older crustal structures intersect the rift axis. In the Gulf of Suez rift, the Zaafarana accommodation zone is located where a shear zone in the Arabian-Nubian Shield meets the rift.[6]

Rift flanks or shoulders are elevated areas around rifts. Rift shoulders are typically about 70 km wide.[7] Contrary to what was previously thought, elevated passive continental margins (EPCM) such as the Brazilian Highlands, the Scandinavian Mountains and India's Western Ghats, are not rift shoulders.[7]

Rift development

[edit]Rift initiation

[edit]The formation of rift basins and strain localization reflects rift maturity. At the onset of rifting, the upper part of the lithosphere starts to extend on a series of initially unconnected normal faults, leading to the development of isolated basins.[8] In subaerial rifts, for example, drainage at the onset of rifting is generally internal, with no element of through drainage.

Mature rift stage

[edit]As the rift evolves, some of the individual fault segments grow, eventually becoming linked together to form the larger bounding faults. Subsequent extension becomes concentrated on these faults. The longer faults and wider fault spacing leads to more continuous areas of fault-related subsidence along the rift axis. Significant uplift of the rift shoulders develops at this stage, strongly influencing drainage and sedimentation in the rift basins.[8]

During the climax of lithospheric rifting, as the crust is thinned, the Earth's surface subsides and the Moho becomes correspondingly raised. At the same time, the mantle lithosphere becomes thinned, causing a rise of the top of the asthenosphere. This brings high heat flow from the upwelling asthenosphere into the thinning lithosphere, heating the orogenic lithosphere for dehydration melting, typically causing extreme metamorphism at high thermal gradients of greater than 30 °C. The metamorphic products are high to ultrahigh temperature granulites and their associated migmatite and granites in collisional orogens, with possible emplacement of metamorphic core complexes in continental rift zones but oceanic core complexes in spreading ridges. This leads to a kind of orogeneses in extensional settings, which is referred as to rifting orogeny.[9]

Post-rift subsidence

[edit]Once rifting ceases, the mantle beneath the rift cools and this is accompanied by a broad area of post-rift subsidence. The amount of subsidence is directly related to the amount of thinning during the rifting phase calculated as the beta factor (initial crustal thickness divided by final crustal thickness), but is also affected by the degree to which the rift basin is filled at each stage, due to the greater density of sediments in contrast to water. The simple 'McKenzie model' of rifting, which considers the rifting stage to be instantaneous, provides a good first order estimate of the amount of crustal thinning from observations of the amount of post-rift subsidence.[10][11] This has generally been replaced by the 'flexural cantilever model', which takes into account the geometry of the rift faults and the flexural isostasy of the upper part of the crust.[12]

Multiphase rifting

[edit]Some rifts show a complex and prolonged history of rifting, with several distinct phases. The North Sea rift shows evidence of several separate rift phases from the Permian through to the Earliest Cretaceous,[13] a period of over 100 million years.

Rifting to break-up

[edit]Rifting may lead to continental breakup and formation of oceanic basins. Successful rifting leads to seafloor spreading along a mid-oceanic ridge and a set of conjugate margins separated by an oceanic basin.[14] Rifting may be active, and controlled by mantle convection. It may also be passive, and driven by far-field tectonic forces that stretch the lithosphere. Margin architecture develops due to spatial and temporal relationships between extensional deformation phases. Margin segmentation eventually leads to the formation of rift domains with variations of the Moho topography, including proximal domain with fault-rotated crustal blocks, necking zone with thinning of crustal basement, distal domain with deep sag basins, ocean-continent transition and oceanic domain.[15]

Deformation and magmatism interact during rift evolution. Magma-rich and magma-poor rifted margins may be formed.[15] Magma-rich margins include major volcanic features. Globally, volcanic margins represent the majority of passive continental margins.[16] Magma-starved rifted margins are affected by large-scale faulting and crustal hyperextension.[17] As a consequence, upper mantle peridotites and gabbros are commonly exposed and serpentinized along extensional detachments at the seafloor.

Magmatism

[edit]

Many rifts are the sites of at least minor magmatic activity, particularly in the early stages of rifting.[18] Alkali basalts and bimodal volcanism are common products of rift-related magmatism.[19][20]

Recent studies indicate that post-collisional granites in collisional orogens are the product of rifting magmatism at converged plate margins.[citation needed]

Economic importance

[edit]The sedimentary rocks associated with continental rifts host important deposits of both minerals and hydrocarbons.[21]

Mineral deposits

[edit]SedEx mineral deposits are found mainly in continental rift settings. They form within post-rift sequences when hydrothermal fluids associated with magmatic activity are expelled at the seabed.[22]

Oil and gas

[edit]Continental rifts are the sites of significant oil and gas accumulations, such as the Viking Graben and the Gulf of Suez Rift. Thirty percent of giant oil and gas fields are found within such a setting.[23] In 1999 it was estimated that there were 200 billion barrels of recoverable oil reserves hosted in rifts. Source rocks are often developed within the sediments filling the active rift (syn-rift), forming either in a lacustrine environment or in a restricted marine environment, although not all rifts contain such sequences. Reservoir rocks may be developed in pre-rift, syn-rift and post-rift sequences.

Effective regional seals may be present within the post-rift sequence if mudstones or evaporites are deposited. Just over half of estimated oil reserves are found associated with rifts containing marine syn-rift and post-rift sequences, just under a quarter in rifts with a non-marine syn-rift and post-rift, and an eighth in non-marine syn-rift with a marine post-rift.[24]

Examples

[edit]- The Asunción Rift in Eastern Paraguay

- The Canadian Arctic Rift System in northern North America

- The East African Rift

- The West and Central African Rift System

- The Red Sea Rift

- The Gulf of California

- The Baikal Rift Zone, the bottom of Lake Baikal is the deepest continental rift on the earth.

- The Gulf of Suez Rift

- Throughout the Basin and Range Province in North America

- The Rio Grande Rift in the southwestern US

- The rift zone that contains the Gulf of Corinth in Greece

- The Reelfoot Rift, an ancient buried failed rift underlying the New Madrid Seismic Zone in the Mississippi embayment

- The Rhine Rift, in southwestern Germany, known as the Upper Rhine valley, part of the European Cenozoic Rift System

- The Taupō Volcanic Zone in the North Island of New Zealand

- The Oslo Graben in Norway

- The Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben in Ontario and Quebec

- The Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province in British Columbia, Yukon and Alaska

- The West Antarctic Rift System in Antarctica

- The Midcontinent Rift System, a late Precambrian rift in central North America

- The Midland Valley in Scotland

- The Fundy Basin, a Triassic rift basin in southeastern Canada

- The Cambay, Kachchh, and Narmada rifts[25] in northwestern Deccan volcanic province of India[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rift valley: definition and geologic significance, Giacomo Corti, The Ethiopian Rift Valley

- ^ Decompressional Melting During Extension of Continental Lithosphere, Jolante van Wijk, MantlePlumes.org

- ^ Plate Tectonics: Lecture 2, Geology Department at University of Leicester

- ^ Leeder, M.R.; Gawthorpe, R.L. (1987). "Sedimentary models for extensional tilt-block/half-graben basins" (PDF). In Coward, M.P.; Dewey, J.F.; Hancock, P.L. (eds.). Continental Extensional Tectonics. Geological Society, Special Publications. Vol. 28. pp. 139–152. ISBN 9780632016051.

- ^ Ebinger, C.J.; Jackson J.A.; Foster A.N.; Hayward N.J. (1999). "Extensional basin geometry and the elastic lithosphere". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 357 (1753): 741–765. Bibcode:1999RSPTA.357..741E. doi:10.1098/rsta.1999.0351. S2CID 91719117.

- ^ Younes, A.I.; McClay K. (2002). "Development of Accommodation Zones in the Gulf of Suez-Red Sea Rift, Egypt". AAPG Bulletin. 86 (6): 1003–1026. doi:10.1306/61EEDC10-173E-11D7-8645000102C1865D. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ a b Green, Paul F.; Japsen, Peter; Chalmers, James A.; Bonow, Johan M.; Duddy, Ian R. (2018). "Post-breakup burial and exhumation of passive continental margins: Seven propositions to inform geodynamic models". Gondwana Research. 53: 58–81. Bibcode:2018GondR..53...58G. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2017.03.007.

- ^ a b Withjack, M.O.; Schlische R.W.; Olsen P.E. (2002). "Rift-basin structure and its influence on sedimentary systems" (PDF). In Renaut R.W. & Ashley G.M. (ed.). Sedimentation in Continental Rifts. Special Publications. Vol. 73. Society for Sedimentary Geology. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Zheng, Y.-F.; Chen, R.-X. (2017). "Regional metamorphism at extreme conditions: Implications for orogeny at convergent plate margins". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 145: 46–73. Bibcode:2017JAESc.145...46Z. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2017.03.009.

- ^ McKenzie, D. (1978). "Some remarks on the development of sedimentary basins" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 40 (1): 25–32. Bibcode:1978E&PSL..40...25M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.459.4779. doi:10.1016/0012-821x(78)90071-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Kusznir, N.J.; Roberts A.M.; Morley C.K. (1995). "Forward and reverse modelling of rift basin formation". In Lambiase J.J. (ed.). Hydrocarbon habitat in rift basins. Special Publications. Vol. 80. London: Geological Society. pp. 33–56. ISBN 9781897799154. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Nøttvedt, A.; Gabrielsen R.H.; Steel R.J. (1995). "Tectonostratigraphy and sedimentary architecture of rift basins, with reference to the northern North Sea". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 12 (8): 881–901. Bibcode:1995MarPG..12..881N. doi:10.1016/0264-8172(95)98853-W.

- ^ Ravnås, R.; Nøttvedt A.; Steel R.J.; Windelstad J. (2000). "Syn-rift sedimentary architectures in the Northern North Sea". Dynamics of the Norwegian Margin. Special Publications. Vol. 167. London: Geological Society. pp. 133–177. ISBN 9781862390560. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Ziegler P.A.; Cloetingh S. (January 2004). "Dynamic processes controlling evolution of rifted basins". Earth-Science Reviews. 64 (1–2): 1–50. Bibcode:2004ESRv...64....1Z. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(03)00041-2.

- ^ a b Péron-Pinvidic G.; Manatschal G.; Osmundsen P.T. (May 2013). "Structural comparison of archetypal Atlantic rifted margins: a review of observations and concepts". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 43: 21–47. Bibcode:2013MarPG..43...21P. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2013.02.002.

- ^ Reston T.J.; Manatschal G. (2011). "Arc-Continent Collision". In Brown D. & Ryan P.D. (ed.). Building blocks of later collision. Frontiers in Earth Sciences.

- ^ Péron-Pinvidic G.; Manatschal G. (2009). "The final rifting evolution at deep magma-poor passive margins from Iberia-Newfoundland: a new point of view". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 98 (7): 1581. Bibcode:2009IJEaS..98.1581P. doi:10.1007/s00531-008-0337-9. S2CID 129442856.

- ^ White, R.S.; McKenzie D. (1989). "Magmatism at Rift Zones: The Generation of Volcanic Margins and Flood Basalts" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 94 (B6): 7685–7729. Bibcode:1989JGR....94.7685W. doi:10.1029/jb094ib06p07685. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Farmer, G.L. (2005). "Continental Basaltic Rocks". In Rudnick R.L. (ed.). Treatise on Geochemistry: The crust. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 97. ISBN 9780080448473. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Cas, R.A.F. (2005). "Volcanoes and the geological cycle". In Marti J. & Ernst G.G. (ed.). Volcanoes and the Environment. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9781139445108. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (1993). "Lake Baikal - A Touchstone for Global Change and Rift Studies". Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Groves, D.I.; Bierlein F.P. (2007). "Geodynamic settings of mineral deposit systems". Journal of the Geological Society. 164 (1): 19–30. Bibcode:2007JGSoc.164...19G. doi:10.1144/0016-76492006-065. S2CID 129680970. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Mann, P.; Gahagan L.; Gordon M.B. (2001). "Tectonic setting of the world's giant oil fields". WorldOil Magazine. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Lambiase, J.J.; Morley C.K. (1999). "Hydrocarbons in rift basins: the role of stratigraphy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 357 (1753): 877–900. Bibcode:1999RSPTA.357..877L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.892.6422. doi:10.1098/rsta.1999.0356. S2CID 129564482.

- ^ Chouhan, A.K. Structural fabric over the seismically active Kachchh rift basin, India: insight from world gravity model 2012. Environ Earth Sci 79, 316 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-020-09068-2

- ^ Chouhan, A.K., Choudhury, P. & Pal, S.K. New evidence for a thin crust and magmatic underplating beneath the Cambay rift basin, Western India through modelling of EIGEN-6C4 gravity data. J Earth Syst Sci 129, 64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-019-1335-y

Further reading

[edit]- Bally, A.W.; Snelson, S. (1980). "Realms of subsidence". Canadian Society for Petroleum Geology Memoir. 6: 9–94.

- Kingston, D.R.; Dishroon, C.P.; Williams, P.A. (December 1983). "Global Basin Classification System" (PDF). AAPG Bulletin. 67 (12): 2175–2193. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- Klemme, H.D (1980). "Petroleum Basins - Classifications and Characteristics". Journal of Petroleum Geology. 3 (2): 187–207. Bibcode:1980JPetG...3..187K. doi:10.1111/j.1747-5457.1980.tb00982.x.