Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Transform fault

View on Wikipedia

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal.[1] It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subduction zone.[2] A transform fault is a special case of a strike-slip fault that also forms a plate boundary.

Most such faults are found in oceanic crust, where they accommodate the lateral offset between segments of divergent boundaries, forming a zigzag pattern. This results from oblique seafloor spreading where the direction of motion is not perpendicular to the trend of the overall divergent boundary. A smaller number of such faults are found on land, although these are generally better-known, such as the San Andreas Fault and North Anatolian Fault.

Nomenclature

[edit]Transform boundaries are also known as conservative plate boundaries because they involve no addition or loss of lithosphere at the Earth's surface.[3]

Background

[edit]Geophysicist and geologist John Tuzo Wilson recognized that the offsets of oceanic ridges by faults do not follow the classical pattern of an offset fence or geological marker in Reid's rebound theory of faulting,[4] from which the sense of slip is derived. The new class of faults,[5] called transform faults, produce slip in the opposite direction from what one would surmise from the standard interpretation of an offset geological feature. Slip along transform faults does not increase the distance between the ridges it separates; the distance remains constant in earthquakes because the ridges are spreading centers. This hypothesis was confirmed in a study of the fault plane solutions that showed the slip on transform faults points in the opposite direction than classical interpretation would suggest.[6]

Difference between transform and transcurrent faults

[edit]Transform faults are closely related to transcurrent faults and are commonly confused. Both types of fault are strike-slip or side-to-side in movement; nevertheless, transform faults always end at a junction with another plate boundary, while transcurrent faults may die out without a junction with another fault. Finally, transform faults form a tectonic plate boundary, while transcurrent faults do not.

Mechanics

[edit]Faults in general are focused areas of deformation or strain, which are the response of built-up stresses in the form of compression, tension, or shear stress in rock at the surface or deep in the Earth's subsurface. Transform faults specifically accommodate lateral strain by transferring displacement between mid-ocean ridges or subduction zones. They also act as the plane of weakness, which may result in splitting in rift zones.[citation needed]

Transform faults and divergent boundaries

[edit]Transform faults are commonly found linking segments of divergent boundaries (mid-oceanic ridges or spreading centres). These mid-oceanic ridges are where new seafloor is constantly created through the upwelling of new basaltic magma. With new seafloor being pushed and pulled out, the older seafloor slowly slides away from the mid-oceanic ridges toward the continents. Although separated only by tens of kilometers, this separation between segments of the ridges causes portions of the seafloor to push past each other in opposing directions. This lateral movement of seafloors past each other is where transform faults are currently active.

Transform faults move differently from a strike-slip fault at the mid-oceanic ridge. Instead of the ridges moving away from each other, as they do in other strike-slip faults, transform-fault ridges remain in the same, fixed locations, and the new ocean seafloor created at the ridges is pushed away from the ridge. Evidence of this motion can be found in paleomagnetic striping on the seafloor.

A paper written by geophysicist Taras Gerya theorizes that the creation of the transform faults between the ridges of the mid-oceanic ridge is attributed to rotated and stretched sections of the mid-oceanic ridge.[7] This occurs over a long period of time with the spreading center or ridge slowly deforming from a straight line to a curved line. Finally, fracturing along these planes forms transform faults. As this takes place, the fault changes from a normal fault with extensional stress to a strike-slip fault with lateral stress.[8] In the study done by Bonatti and Crane,[who?] peridotite and gabbro rocks were discovered in the edges of the transform ridges. These rocks are created deep inside the Earth's mantle and then rapidly exhumed to the surface.[8] This evidence helps to prove that new seafloor is being created at the mid-oceanic ridges and further supports the theory of plate tectonics.

Active transform faults are between two tectonic structures or faults. Fracture zones represent the previously active transform-fault lines, which have since passed the active transform zone and are being pushed toward the continents. These elevated ridges on the ocean floor can be traced for hundreds of miles and in some cases even from one continent across an ocean to the other continent.

Types

[edit]In his work on transform-fault systems, geologist Tuzo Wilson said that transform faults must be connected to other faults or tectonic-plate boundaries on both ends; because of that requirement, transform faults can grow in length, keep a constant length, or decrease in length.[5] These length changes are dependent on which type of fault or tectonic structure connect with the transform fault. Wilson described six types of transform faults:

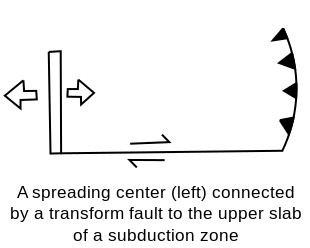

Growing length: In situations where a transform fault links a spreading center and the upper block of a subduction zone or where two upper blocks of subduction zones are linked, the transform fault itself will grow in length.[5]

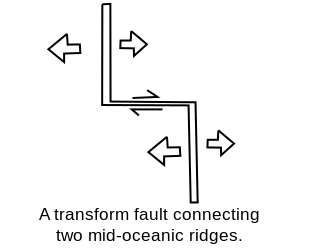

Constant length: In other cases, transform faults will remain at a constant length. This steadiness can be attributed to many different causes. In the case of ridge-to-ridge transforms, the constancy is caused by the continuous growth by both ridges outward, canceling any change in length. The opposite occurs when a ridge linked to a subducting plate, where all the lithosphere (new seafloor) being created by the ridge is subducted, or swallowed up, by the subduction zone.[5] Finally, when two upper subduction plates are linked there is no change in length. This is due to the plates moving parallel with each other and no new lithosphere is being created to change that length.

Decreasing length faults: In rare cases, transform faults can shrink in length. These occur when two descending subduction plates are linked by a transform fault. In time as the plates are subducted, the transform fault will decrease in length until the transform fault disappears completely, leaving only two subduction zones facing in opposite directions.[5]

Examples

[edit]

The most prominent examples of the mid-oceanic ridge transform zones are in the Atlantic Ocean between South America and Africa. Known as the St. Paul, Romanche, Chain, and Ascension fracture zones, these areas have deep, easily identifiable transform faults and ridges. Other locations include: the East Pacific Ridge located in the South Eastern Pacific Ocean, which meets up with San Andreas Fault to the North.

Transform faults are not limited to oceanic crust and spreading centers; many of them are on continental margins. The best example is the San Andreas Fault on the Pacific coast of the United States. The San Andreas Fault links the East Pacific Rise off the West coast of Mexico (Gulf of California) to the Mendocino triple junction (Part of the Juan de Fuca plate) off the coast of the Northwestern United States, making it a ridge-to-transform-style fault.[5] The formation of the San Andreas Fault system occurred fairly recently during the Oligocene Period between 34 million and 24 million years ago.[9] During this period, the Farallon plate, followed by the Pacific plate, collided into the North American plate.[9] The collision led to the subduction of the Farallon plate underneath the North American plate. Once the spreading center separating the Pacific and the Farallon plates was subducted beneath the North American plate, the San Andreas Continental Transform-Fault system was created.[9]

In New Zealand, the South Island's Alpine Fault is a transform fault for much of its length. This has resulted in the folded land of the Southland Syncline being split into an eastern and western section several hundred kilometres apart. The majority of the syncline is found in Southland and The Catlins in the island's southeast, but a smaller section is also present in the Tasman District in the island's northwest.

Another example is the Húsavík‐Flatey fault. This oceanic transform fault is nearly completely submerged, but ~10 km is exposed in northern Iceland, near the town of Húsavík. There, it manifests as a series of half-grabens and sharp fault scarps. Since oceanic transform faults are often difficult to research because of their submerged nature, this fault represents a rare opportunity for research. Scientists inspected Holocene earthquake activity by looking cross sections of the fault, and found the approximate earthquake frequency in the region to be 600 ± 200 years.[10]

Other examples include:

See also

[edit]- Fracture zone – Linear feature on the ocean floor

- Leaky transform fault – Transform fault producing new crust

- List of tectonic plate interactions – Movements of Earth's lithosphere

- Plate tectonics – Movement of Earth's lithosphere

- Strike-slip tectonics – Deformation dominated by horizontal movement in Earth's lithosphere

- Structural geology – Science of the description and interpretation of deformation in the Earth's crust

References

[edit]- ^ Moores E.M.; Twiss R.J. (2014). Tectonics. Waveland Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-4786-2660-2.

- ^ Kearey, K. A. (2007). Global Tectonics. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 84–90.

- ^ "Plate Tectonics". British Geological Survey. 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Reid, H.F., (1910). The Mechanics of the Earthquake. in The California Earthquake of April 18, 1906, Report of the State Earthquake Investigation Commission, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington D.C.

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson, J.T. (24 July 1965). "A new class of faults and their bearing on continental drift". Nature. 207 (4995): 343–347. Bibcode:1965Natur.207..343W. doi:10.1038/207343a0. S2CID 4294401.

- ^ Sykes, L.R. (1967). Mechanism of earthquakes and nature of faulting on the mid-oceanic ridges, Journal of Geophysical Research, 72, 5–27.

- ^ Gerya, T. (2010). "Dynamical Instability Produces Transform Faults at Mid-Ocean Ridges". Science. 329 (5995): 1047–1050. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1047G. doi:10.1126/science.1191349. PMID 20798313. S2CID 10943308.

- ^ a b Bonatti, Enrico; Crane, Kathleen (1984). "Oceanic Fracture Zones". Scientific American. 250 (5): 40–52. Bibcode:1984SciAm.250e..40B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0584-40.

- ^ a b c Atwater, Tanya (1970). "Implications of Plate Tectonics for the Cenozoic Tectonic Evolution of Western North America". Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 81 (12): 3513–3536. Bibcode:1970GSAB...81.3513A. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1970)81[3513:ioptft]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Matrau, Rémi; Klinger, Yann; Thorðarson, Thorvaldur; Guðmundsdóttir, Esther R.; Avşar, Ulas; Parisi, Laura; Fittipaldi, Margherita; Jónsson, Sigurjón (2024-03-28). "Evidence for Holocene Earthquakes along the Húsavík‐Flatey Fault in North Iceland: Implications for the Seismic Behavior of Oceanic Transform Faults". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 114 (4): 1966–1993. doi:10.1785/0120230119. ISSN 0037-1106.