Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Passive margin

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2016) |

A passive margin is the transition between oceanic and continental lithosphere that is not an active plate margin. A passive margin forms by sedimentation above an ancient rift, now marked by transitional lithosphere. Continental rifting forms new ocean basins. Eventually the continental rift forms a mid-ocean ridge and the locus of extension moves away from the continent-ocean boundary. The transition between the continental and oceanic lithosphere that was originally formed by rifting is known as a passive margin.

In summary, passive margins represent broad, non-tectonically active transitions between continental and oceanic lithosphere that evolve from continental rifting to seafloor spreading and subsequent thermal subsidence, producing extensive sedimentary wedges above highly attenuated transitional crust. Recent studies emphasize that passive margin architecture varies laterally over short distances with changes in crustal extension and magmatic flux, leading to magma-poor, magma-rich e intermediate margin segments that influence crustal structure, subsidence history and sediment distribution. These heterogeneities affect basin evolution, resource potential and margin morphology along rifted continental margins.

Global distribution

[edit]

Passive margins are found at every ocean and continent boundary that is not marked by a strike-slip fault or a subduction zone. Passive margins define the region around the Arctic Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, and western Indian Ocean, and define the entire coasts of Africa, Australia, Greenland, and the Indian Subcontinent. They are also found on the east coast of North America and South America, in Western Europe and most of Antarctica. Northeast Asia also contains some passive margins.

Key components

[edit]Active vs. passive margins

[edit]The distinction between active and passive margins refers to whether a crustal boundary between oceanic lithosphere and continental lithosphere is a plate boundary. Active margins are found on the edge of a continent where subduction occurs. These are often marked by uplift and volcanic mountain belts on the continental plate. Less often there is a strike-slip fault, as defines the southern coastline of West Africa. Most of the eastern Indian Ocean and nearly all of the Pacific Ocean margin are examples of active margins. While a weld between oceanic and continental lithosphere is called a passive margin, it is not an inactive margin. Active subsidence, sedimentation, growth faulting, pore fluid formation and migration are all active processes on passive margins. Passive margins are only passive in that they are not active plate boundaries.

Morphology

[edit]

Passive margins consist of both onshore coastal plain and offshore continental shelf-slope-rise triads. Coastal plains are often dominated by fluvial processes, while the continental shelf is dominated by deltaic and longshore current processes. The great rivers (Amazon, Orinoco, Congo, Nile, Ganges, Yellow, Yangtze, and Mackenzie rivers) drain across passive margins. Extensive estuaries are common on mature passive margins. Although there are many kinds of passive margins, the morphologies of most passive margins are remarkably similar. Typically they consist of a continental shelf, continental slope, continental rise, and abyssal plain. The morphological expression of these features are largely defined by the underlying transitional crust and the sedimentation above it. Passive margins defined by a large fluvial sediment budget and those dominated by coral and other biogenous processes generally have a similar morphology. In addition, the shelf break seems to mark the maximum Neogene lowstand, defined by the glacial maxima. The outer continental shelf and slope may be cut by great submarine canyons, which mark the offshore continuation of rivers.

At high latitudes and during glaciations, the nearshore morphology of passive margins may reflect glacial processes, such as the fjords of Greenland and Norway.

Cross-section

[edit]

The main features of passive margins lie underneath the external characters. Beneath passive margins the transition between the continental and oceanic crust is a broad transition known as transitional crust. The subsided continental crust is marked by normal faults that dip seaward. The faulted crust transitions into oceanic crust and may be deeply buried due to thermal subsidence and the mass of sediment that collects above it. The lithosphere beneath passive margins is known as transitional lithosphere. The lithosphere thins seaward as it transitions seaward to oceanic crust. Different kinds of transitional crust form, depending on how fast rifting occurs and how hot the underlying mantle was at the time of rifting. Volcanic passive margins represent one endmember transitional crust type, the other endmember (amagmatic) type is the rifted passive margin. Volcanic passive margins also are marked by numerous dykes and igneous intrusions within the subsided continental crust. There are typically a lot of dykes formed perpendicular to the seaward-dipping lava flows and sills. Igneous intrusions within the crust cause lava flows along the top of the subsided continental crust and form seaward-dipping reflectors.

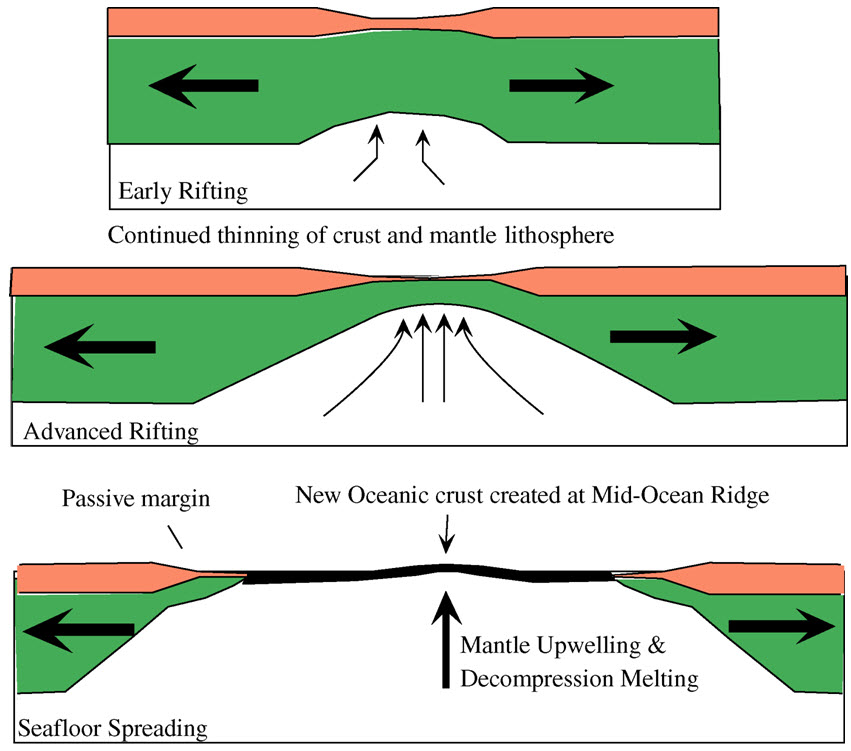

Subsidence mechanisms

[edit]Passive margins are characterized by thick accumulations of sediments. Space for these sediments is called accommodation and is due to subsidence of especially the transitional crust. Subsidence is ultimately caused by gravitational equilibrium that is established between the crustal tracts, known as isostasy. Isostasy controls the uplift of the rift flank and the subsequent subsidence of the evolving passive margin and is mostly reflected by changes in heat flow. Heat flow at passive margins changes significantly over its lifespan, high at the beginning and decreasing with age. In the initial stage, the continental crust and lithosphere is stretched and thinned due to plate movement (plate tectonics) and associated igneous activity. The very thin lithosphere beneath the rift allows the upwelling mantle to melt by decompression. Lithospheric thinning also allows the asthenosphere to rise closer to the surface, heating the overlying lithosphere by conduction and advection of heat by intrusive dykes. Heating reduces the density of the lithosphere and elevates the lower crust and lithosphere. In addition, mantle plumes may heat the lithosphere and cause prodigious igneous activity. Once a mid-oceanic ridge forms and seafloor spreading begins, the original site of rifting is separated into conjugate passive margins (for example, the eastern US and NW African margins were parts of the same rift in early Mesozoic time and are now conjugate margins) and migrates away from the zone of mantle upwelling and heating and cooling begins. The mantle lithosphere below the thinned and faulted continental oceanic transition cools, thickens, increases in density and thus begins to subside. The accumulation of sediments above the subsiding transitional crust and lithosphere further depresses the transitional crust.

Classification

[edit]There are four different perspectives needed to classify passive margins:

- map-view formation geometry (rifted, sheared, and transtensional),

- nature of transitional crust (volcanic and non-volcanic),

- whether the transitional crust represents a continuous change from normal continental to normal oceanic crust or this includes isolated rifts and stranded continental blocks (simple and complex), and

- sedimentation (carbonate-dominated, clastic-dominated, or sediment starved).

The first describes the relationship between rift orientation and plate motion, the second describes the nature of transitional crust, and the third describes post-rift sedimentation. All three perspectives need to be considered in describing a passive margin. In fact, passive margins are extremely long, and vary along their length in rift geometry, nature of transitional crust, and sediment supply; it is more appropriate to subdivide individual passive margins into segments on this basis and apply the threefold classification to each segment.

Geometry of passive margins

[edit]Rifted margin

[edit]This is the typical way that passive margins form, as separated continental tracts move perpendicular to the coastline. This is how the Central Atlantic opened, beginning in Jurassic time. Faulting tends to be listric: normal faults that flatten with depth.

Sheared margin

[edit]Sheared margins form where continental breakup was associated with strike-slip faulting. A good example of this type of margin is found on the south-facing coast of west Africa. Sheared margins are highly complex and tend to be rather narrow. They also differ from rifted passive margins in structural style and thermal evolution during continental breakup. As the seafloor spreading axis moves along the margin, thermal uplift produces a ridge. This ridge traps sediments, thus allowing for thick sequences to accumulate. These types of passive margins are less volcanic.

Transtensional margin

[edit]This type of passive margin develops where rifting is oblique to the coastline, as is now occurring in the Gulf of California.

Nature of transitional crust

[edit]Transitional crust, separating true oceanic and continental crusts, is the foundation of any passive margin. This forms during the rifting stage and consists of two endmembers: volcanic and non-volcanic. This classification scheme only applies to rifted and transtensional margin; transitional crust of sheared margins is very poorly known.

Non-volcanic rifted margin

[edit]Non-volcanic margins are formed when extension is accompanied by little mantle melting and volcanism. Non-volcanic transitional crust consists of stretched and thinned continental crust. Non-volcanic margins are typically characterized by continentward-dipping seismic reflectors (rotated crustal blocks and associated sediments) and low P wave velocities (<7.0 km/s) in the lower part of the transitional crust.

Volcanic rifted margin

[edit]Volcanic margins form part of large igneous provinces, which are characterised by massive emplacements of mafic extrusives and intrusive rocks over very short time periods. Volcanic margins form when rifting is accompanied by significant mantle melting, with volcanism occurring before and/or during continental breakup. The transitional crust of volcanic margins is composed of basaltic igneous rocks, including lava flows, sills, dykes, and gabbro.

Volcanic margins are usually distinguished from non-volcanic (or magma-poor) margins (e.g. the Iberian margin, Newfoundland margin) which do not contain large amounts of extrusive and/or intrusive rocks and may exhibit crustal features such as unroofed, serpentinized mantle. Volcanic margins are known to differ from magma-poor margins in a number of ways:

- A transitional crust composed of basaltic igneous rocks, including lava flows, sills, dykes, and gabbros

- A huge volume of basalt flows, typically expressed as seaward-dipping reflector sequences (SDRS) rotated during the early stages of crustal accretion (breakup stage)

- The presence of numerous sill/dyke and vent complexes intruding into the adjacent basin

- The lack of significant passive-margin subsidence during and after breakup

- The presence of a lower crust with anomalously high seismic P wave velocities (Vp=7.1-7.8 km/s) – referred to as lower crustal bodies (LCBs) in the geologic literature

The high velocities (Vp > 7 km) and large thicknesses of the LCBs are evidence that supports the case for plume-fed accretion (mafic thickening) underplating the crust during continental breakup. LCBs are located along the continent-ocean transition but can sometimes extend beneath the continental part of the rifted margin (as observed in the mid-Norwegian margin for example). In the continental domain, there are still open discussion on their real nature, chronology, geodynamic and petroleum implications.[1]

Examples of volcanic margins:

- The Yemen margin

- The East Australian margin

- The West Indian margin

- The Hatton-Rockal margin

- The U.S. East Coast

- The mid-Norwegian margin

- The Brazilian margins

- The Namibian margin

- The East Greenland margin

- The West Greenland margin

Examples of non-volcanic margins:

- The Newfoundland Margin

- The Iberian Margin

- The Margins of the Labrador Sea (Labrador and Southwest Greenland)

Heterogeneity of transitional crust

[edit]Simple transitional crust

[edit]Passive margins of this type show a simple progression through the transitional crust, from normal continental to normal oceanic crusts. The passive margin offshore Texas is a good example.

Complex transitional crust

[edit]This type of transitional crust is characterized by abandoned rifts and continental blocks, such as the Blake Plateau, Grand Banks, or Bahama Islands offshore eastern Florida.

Sedimentation

[edit]A fourth way to classify passive margins is according to the nature of sedimentation of the mature passive margin. Sedimentation continues throughout the life of a passive margin. Sedimentation changes rapidly and progressively during the initial stages of passive margin formation because rifting begins on land, becoming marine as the rift opens and a true passive margin is established. Consequently, the sedimentation history of a passive margin begins with fluvial, lacustrine, or other subaerial deposits, evolving with time depending on how the rifting occurred and how, when, and by what type of sediment it varies.

Constructional

[edit]Constructional margins are the "classic" mode of passive margin sedimentation. Normal sedimentation results from the transport and deposition of sand, silt, and clay by rivers via deltas and redistribution of these sediments by longshore currents. The nature of sediments can change remarkably along a passive margin, due to interactions between carbonate sediment production, clastic input from rivers, and alongshore transport. Where clastic sediment inputs are small, biogenic sedimentation can dominate especially nearshore sedimentation. The Gulf of Mexico passive margin along the southern United States is an excellent example of this, with muddy and sandy coastal environments down current (west) from the Mississippi River Delta and beaches of carbonate sand to the east. The thick layers of sediment gradually thin with increasing distance offshore, depending on subsidence of the passive margin and the efficacy of offshore transport mechanisms such as turbidity currents and submarine channels.

Development of the shelf edge and its migration through time is critical to the development of a passive margin. The location of the shelf edge break reflects complex interaction between sedimentation, sealevel, and the presence of sediment dams. Coral reefs serve as bulwarks that allow sediment to accumulate between them and the shore, cutting off sediment supply to deeper water. Another type of sediment dam results from the presence of salt domes, as are common along the Texas and Louisiana passive margin.

Starved

[edit]Sediment-starved margins produce narrow continental shelves and passive margins. This is especially common in arid regions, where there is little transport of sediment by rivers or redistribution by longshore currents. The Red Sea is a good example of a sediment-starved passive margin.

Formation

[edit]

There are three main stages in the formation of passive margins:

- In the first stage a continental rift is established due to stretching and thinning of the crust and lithosphere by plate movement. This is the beginning of the continental crust subsidence. Drainage is generally away from the rift at this stage.

- The second stage leads to the formation of an oceanic basin, similar to the modern Red Sea. The subsiding continental crust undergoes normal faulting as transitional marine conditions are established. Areas with restricted sea water circulation coupled with arid climate create evaporite deposits. Crust and lithosphere stretching and thinning are still taking place in this stage. Volcanic passive margins also have igneous intrusions and dykes during this stage.

- The last stage in formation happens only when crustal stretching ceases and the transitional crust and lithosphere subsides as a result of cooling and thickening (thermal subsidence). Drainage starts flowing towards the passive margin causing sediment to accumulate over it.

Economic significance

[edit]Passive margins are important exploration targets for petroleum. Mann et al. (2001) classified 592 giant oil fields into six basin and tectonic-setting categories, and noted that continental passive margins account for 31% of giants. Continental rifts (which are likely to evolve into passive margins with time) contain another 30% of the world's giant oil fields. Basins associated with collision zones and subduction zones are where most of the remaining giant oil fields are found.

Passive margins are petroleum storehouses because these are associated with favorable conditions for accumulation and maturation of organic matter. Early continental rifting conditions led to the development of anoxic basins, large sediment and organic flux, and the preservation of organic matter that led to oil and gas deposits. Crude oil will form from these deposits. These are the localities in which petroleum resources are most profitable and productive. Productive fields are found in passive margins around the globe, including the Gulf of Mexico, western Scandinavia, and Western Australia.

Law of the Sea

[edit]International discussions about who controls the resources of passive margins are the focus of law of the sea negotiations. Continental shelves are important parts of national exclusive economic zones, important for seafloor mineral deposits (including oil and gas) and fisheries.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Norwegian volcanic margin Archived June 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Hillis, R. D.; R. D. Müller (2003). Evolution and Dynamics of the Australian Plate. Geological Society of America.

- Morelock, Jack (2004). "Margin Structure". Geological Oceanography. Archived from the original on 2017-01-10. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- Curray, J. R. (1980). "The IPOD Programme on Passive Continental Margins". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. A 294 (1409): 17–33. Bibcode:1980RSPTA.294...17C. doi:10.1098/rsta.1980.0008. JSTOR 36571. S2CID 121621142.

- "Diapir". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

- "Petroleum". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. | http://www.mantleplumes.org/VM_Norway.html

- "UNIL: Subsidence Curves". Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the University of Lausanne. Retrieved 2007-12-02. [dead link]

- "P. Mann, L. Gahagan, and M.B. Gordon, 2001. Tectonic setting of the world's giant oil fields, Part 1 A new classification scheme of the world's giant fields reveals the regional geology where explorationists may be most likely to find future giants". Archived from the original on 2008-02-09.

- Bird, Dale (February 2001). "Shear Margins". The Leading Edge. 20 (2): 150–159. doi:10.1190/1.1438894.

- Fraser, S.I.; Fraser, A. J.; Lentini, M. R.; Gawthorpe, R. L. (2007). "Return to rifts – the next wave: Fresh insights into the Petroleum geology of global rift basins". Petroleum Geoscience. 13 (2): 99–104. Bibcode:2007PetGe..13...99F. doi:10.1144/1354-079307-749. S2CID 130607197.

- Gernigon, L.; J.C Ringenbach; S. Planke; B. Le Gall (2004). "Deep structures and breakup along volcanic rifted margins: Insights from integrated studies along the outer Vøring Basin (Norway)". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 21–3 (3): 363–372. Bibcode:2004MarPG..21..363G. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2004.01.005. | http://www.mantleplumes.org/VM_Norway.html

- Continental Margins Committee, ed. (1989). Margins: A Research Initiative for Interdisciplinary Studies of the Processes Attending Lithospheric Extension and Convergence. The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/1500. ISBN 978-0-309-04188-1. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- Geoffroy, Laurent (October 2005). "Volcanic Passive Margins" (PDF). C. R. Geoscience 337 (in French and English). Elsevier SAS. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- R. A. Scrutton, ed. (1982). Dynamics of Passive Margins. USA: American Geophysical Union.

- Mjelde, R.; Raum, T.; Murai, Y.; Takanami, T. (2007). "Continent-ocean-transitions: Review, and a new tectono-magmatic model of the Vøring Plateau, NE Atlantic". Journal of Geodynamics. 43 (3): 374–392. Bibcode:2007JGeo...43..374M. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2006.09.013.

- Mikael Arnemann, Vitor Abreu, Sidnei Rostirolla, Eduardo Barboza, Lateral changes of crustal extension and passive margin type along the Brazilian southeastern margin, Journal of Sea Research, Volume 196, 2023, 102459, ISSN 1385-1101.<https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2023.102459.>

- WIKIPEDIA CONTRIBUTORS. Non-volcanic passive margins. Disponível em: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-volcanic_passive_margins?utm_source>.