Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cursus publicus

View on Wikipedia

The cursus publicus (Latin: "the public way"; Ancient Greek: δημόσιος δρόμος, dēmósios drómos) was the state mandated and supervised courier and transportation service of the Roman Empire,[1][2] the use of which continued into the Eastern Roman Empire and the Ostrogothic Kingdom. It was a system based on obligations placed on private persons by the Roman State. As contractors, called mancipes, they provided the equipment, animals, and wagons. In the Early Empire compensation had to be paid but this had fallen into abeyance in Late Antiquity when maintenance was charged to the inhabitants along the routes. The service contained only those personnel necessary for administration and operation. These included veterinarians, wagon-wrights, and grooms. The couriers and wagon drivers did not belong to the service: whether public servants or private individuals, they used facilities requisitioned from local individuals and communities.[3] The costs in Late Antiquity were charged to the provincials as part of the provincial tax obligations in the form of a liturgy/munus on private individual taxpayers.

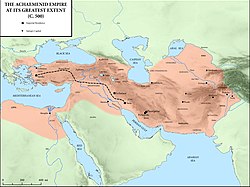

The Emperor Augustus created it to transport messages, officials, and tax revenues between the provinces and Italy.[4][5][6] The service was still fully functioning in the first half of the sixth century in the Eastern Empire, when the historian Procopius accuses Emperor Justinian of dismantling most of its sections, except for the route leading to the Persian border.[7] The extent of the cursus publicus is shown in the Tabula Peutingeriana, a map of the Roman road network dating from around AD 400.[8]

Structure

[edit]The cursus publicus was only accessible to the government or the military.[9][10][11][12] Citizens could only use the cursus publicus if the government permitted it.[13][14] People who were not allowed to use the services of the cursus publicus would use slaves or acquaintances to carry their mail.[15] The government would give a special permit to these individuals which would signify that they were allowed to use the Cursus Publicus's services.[16][17][18][19] This diploma, issued by the emperor himself, was necessary to use the services supplied by the cursus publicus.[20][21][22] They would contain the name of the person who had been awarded this privilege, the time frame it was valid in, the means of travel, the route, and the lodgings.[23] Abuses of the system existed, for governors and minor appointees used the diplomata to give themselves and their families free transport. Forgeries and stolen diplomata were also used.[24] Pliny the Younger and Trajan write about the necessity of those who wish to send things via the imperial post to keep up-to-date licenses.[25] If there was a dispute on the validity of one of these diplomas a judge would be asked to settle the conflict. These documents were handed out rarely due to the high cost in using and maintaining the cursus publicus.[26] This organization would deliver mail,[27] military equipment and taxes.[28][29] Alongside this,[30] they also worked as an imperial intelligence agency.[31][32][33]

Although the government supervised the functioning and maintenance of the network of change stations with repair facilities (mutationes)[34][35] and full service change stations with lodging (mansions),[36][37][38][39] the system was not a postal service in the same way as the modern British Royal Mail, nor a series of state-owned and operated hotels and repair facilities. As Altay Coskun notes in a review of Anne Kolb's work done in German, the system "simply provided an infrastructure for magistrates and messengers who traveled through the Empire. It consisted of thousands of stations placed along the main roads;[40] these had to supply fresh horses, mules,[41] donkeys, and oxen, as well as carts, food, fodder, and accommodation." [42][43][44] The one who was sending a missive would have to supply the courier, and the stations had to be supplied out of the resources of the local areas through which the roads passed. As seen in several rescripts and in the correspondence of Trajan and Pliny, the emperor would sometimes pay for the cost of sending an ambassador to Rome along the cursus publicus, particularly in the case of just causes. Alongside this, there were relay points or change stations (stationes) provided horses to dispatch riders and (usually) soldiers as well as vehicles for magistrates or officers of the court.[45][46] The vehicles were called clabulae, but little is known of them. Despite this, they carried out their duties on foot.[47][48]

Augustus, at first, followed the Persian method of having mail handed from one courier to the next, but he soon switched to a system by which one man made the entire journey with the parcel. Although it is possible that a courier service existed for a time under the Roman Republic, the clearest reference by Suetonius states that Augustus created the system.[49][50][51] Suetonius states:[52][53][54]

To enable what was going on in each of the provinces to be reported and known more speedily and promptly, he at first stationed young men at short intervals along the military roads, and afterwards post-chaises. The latter has seemed the more convenient arrangement, since the same men who bring the dispatches from any place can, if occasion demands, be questioned as well.

— Suetonius, The Lives of the Caesars, The Life of Augustus

Another term, perhaps more accurate if less common, for the cursus publicus is the cursus vehicularis,[55] particularly in the period before the reforms of Diocletian.[56] At least one praefectus vehiculorum, Lucius Volusius Maecianus,[57] is known; he held the office during the reign of Antoninus Pius.[58] Presumably, he had some sort of supervisory responsibility to ensure the effective operation of the network of stations throughout the Empire and to discourage abuse of the facility by those not entitled to use it. There is evidence that inspectors oversaw the functioning of the system in the provinces, and it may be conjectured that they reported to the praefectus in Rome. However, the office does not seem to have been considered a full-time position because Maecianus was also the law tutor of the young Marcus Aurelius, apparently his main function.[57] The praefectus vehiculorum was tasked with managing the cursus publicus in Italy. Outside of Italy, local governors and officials managed the organization.[59]

Following the reforms of Diocletian and Constantine I, the service was divided in two sections: the fast (Latin: cursus velox, Greek: ὀξὺς δρόμος) and the regular (Latin: cursus clabularis, Greek: πλατὺς δρόμος).[60][61][62] The fast section provided horses,[63][64] divided into veredi ("saddle-horses") and parhippi ("pack-horses"), and mules, and the slow section provided only oxen.[52][65][66] The existence of the cursus clabularis service shows that it was used to move heavy goods as well as to facilitate the travel of high officials and the carriage of government messages.[67] Maintenance was charged to the provincials under the supervision of the governors under the general supervision of the diocesan vicars and praetorian prefects.[68]

Most members of the Cursus publicus were recruited from the military.[69] Usually members of the Cursus publicus were formerly speculatores (members of a reconnaissance agency).[70]

History

[edit]

The Romans adapted their state post from the ancient Persian network of the royal mounted couriers,[71] the angarium.[72] As Herodotus reports, the Persians had a remarkably efficient means of transmitting messages important to the functioning of the kingdom, called the Royal Road.[73][74] The riders would be stationed at a day's ride along the road, and the letters would be handed from one courier to another as they made a journey of a day’s length, which allowed messages to travel fast.[75][76] It was established by Augustus to replace the system of private couriers which was used during the Roman Republic.[77][78][79]

Tacitus says that couriers from Judea and Syria brought news to Vitellius that the legions of the East had sworn allegiance to him,[80] and this also shows that the relay system was displaced by a system in which the original messenger made the entire journey. Augustus modified the Persian system, as Suetonius notes, because a courier who travels the whole distance could be interrogated by the emperor, upon arrival, to receive additional information orally. That may have had the additional advantage of adding security to the post, as one man had the responsibility to answer for the successful delivery of the message. That does not come without a cost, as the Romans could not relay a message as quickly as they could if it passed from one rider to the next.

The cursus publicus was run by municipal magistrates until the reign of Nerva,[81] who reformed the systems so it would be run by the Res mancipi.[82] Many Roman roads were constructed or expanded to facilitate the movement of the cursus publicus.[83][84][85] After the fall of the Roman Empire the Cursus Publicus survived in the Byzantine Empire and the former territories of the Western Roman Empire.[86][87][88] Under the Byzantine Empire the agentes in rebus supervised the cursus publicus and ensured they had the necessary supplies and lodgings.[89][90][29] They were also tasked with ensuring the legal validity of the diplomas their users possessed.[91]

Speed of post

[edit]Procopius provides one of the few direct descriptions of the Roman post that allows an estimation the average rate of travel overland. In the 6th century, he described earlier times:[92]

The earlier Emperors, in order to obtain information as quickly as possible regarding the movements of the enemy in any quarter, sedition, unforeseen accidents in individual cities, and the actions of the governors or other persons in all parts of the Empire, and also in order that the annual tributes might be sent up without danger or delay, had established a rapid service of public couriers throughout their dominion according to the following system. As a day’s journey for an active man they fixed eight ‘stages,’ or sometimes fewer, but as a general rule not less than five. In every stage there were forty horses and a number of grooms in proportion. The couriers appointed for the work, by making use of relays of excellent horses, when engaged in the duties I have mentioned, often covered in a single day, by this means, as great a distance as they would otherwise have covered in ten.

If the distance between change stations is known, and five to eight is the typical number, the speed of the cursus publicus can be calculated. A. M. Ramsey writes,[93] "It appears from the Jerusalem Itinerary that the mansiones, or night quarters on the roads, were about twenty-five [Roman] miles [23 mi or 37 km] apart, and, as Friedlander points out, the distance between Bethlehem and Alexandria (about 400 Roman miles [368 mi or 592 km]) was reckoned to be sixteen mansiones, that between Edessa and Jerusalem (by Antioch nearly 625 [Roman] miles [574 mi or 924 km]) twenty-five mansiones. Although no Itinerary gives a complete list of mutationes and mansiones for any road, the general rule seems to have been two mutationes between each two mansiones or 37 km (23 miles). This would make the 'stage' about eight and a third Roman miles [7.7 mi or 12.4 km]." The typical trip was 38 to 62 miles (61–100 km) per day or 5 to 8 stages. But this is in normal, not emergency, conditions, when a single rider could cover 160 km (100 miles) or more in a day.

There are several cases in which urgent news or eager officials traveled at a faster rate. There is the journey of Tiberius mentioned by Valerius Maximus, the news of the mutiny of Galba as recorded by Tacitus, and the news of the death of Nero as described by Plutarch.[94] In the last two cases, it is worth keeping in mind that bad news traveled faster than good news, and quite explicitly: a laurel was attached to the correspondence with news of victory, but a feather, as indicating haste, was fixed to the spear of a messenger carrying bad news. In all three cases, as A. M. Ramsey points out, the journey is especially urgent, and the time of travel may be recorded because of its exceptional rapidness. Such cases could not be used to find a typical speed of the Roman post for carrying the vast majority of items.

Ramsey, following Wilcken, illustrates the speed of the Roman post over land with examples of the amount of time it would take a message to travel from Rome to Egypt about the accession of a new emperor (in a season other than summer, when the message would travel by sea from Rome to Alexandria). In the case of Pertinax, news of the accession, which took place on January 1, AD 193, took over sixty-three days to reach Egypt, being announced on March 6 in Alexandria. Since the route that would be taken over land consisted of about 3,177 kilometres (1,974 mi)—1,400 kilometres (870 mi) from Rome to Byzantium, including the sea crossing and almost 1,800 kilometres (1,100 mi) from Byzantium to Alexandria)—and since it took about sixty-three days or a little more for the message to arrive in Alexandria, this confirms an average rate of about 32 miles (51 km) per day for this journey.

Another example, based on a Latin inscription, is cited by Ramsey. Gaius Caesar, grandson of Augustus, died on February 21, AD 4, in Limyra, which is on the coast of Lycia.[95] The news of death is found on an inscription dated April 2 at Pisa. The amount of time that the message took to arrive at Pisa is not less than thirty-six days. Since a voyage by sea would be too dangerous at this time of year, the message was sent over land, a distance of about 1,345 miles (2,165 km). This confirms the calculation of an average rate of about fifty km per day.

In his article “New Evidence for the Speed of the Roman Imperial Post,”[96] Eliot agrees with A. M. Ramsey that the typical speed was about 50 miles (80 km) per day and illustrates this with another instance,[97] the time that it took news of the proclamation of the emperor Septimius Severus to reach Rome from Carnuntum.

These estimates are for journeys that took place over land, making use of the cursus publicus (or, cursus vehicularis). Lionel Casson, in his book on ancient sea travel, gives statistics for the amount of time that sixteen voyages took between various ports in the Roman Empire. These voyages, which were made by and recorded by the Romans, are recorded specifically as taking place under favorable wind conditions. Under such conditions, when the average is computed, a vessel could travel by sail at a speed of about 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph) or 120 miles (190 km) per day. Casson provides another table of ten voyages made under unfavorable conditions. With these voyages, the average speed is about 2 knots (3.7 km/h; 2.3 mph) or 50 miles (80 km) per day.

Area of operation

[edit]The cursus operated in Italy and the more advanced provinces. There was only one in Egypt and one in Asia Minor, as Pliny's letters to Trajan attest. It was common for a village to exist every 12 miles (19 km) or so, and there a courier might rest at large, privately owned mansiones. Operated by a manceps, or a business man, the mansiones provided food and lodging,[98] and care and a blacksmith for the horses. The cursus also used communities located along the imperial highways. These towns very often provided food and horses to messengers of the Legions, theoretically receiving reimbursement, and were responsible for the care of their section of the Roman roads. Disputes arose naturally, and for a time the central administration participated more directly.[99]

Financial costs

[edit]Costs for the cursus publicus were always high, and its maintenance could not always be guaranteed.[citation needed] Around the time of Nerva, in the late first century, the general cost was transferred to the fiscus (Treasury). Further centralization came during the reign of Hadrian, who created an actual administration under a prefect, who bore the title praefectus vehiculorum. The cursus publicus provided the infrastructure of change stations and overnight accommodation that allowed for the fairly rapid delivery of messages and especially in regard to military matters. The private citizen, however, sent letters and messages to friends across the sea with slaves and travelling associates. Most news reached its destination eventually.

In an effort to restrict abuse of the post, Julian (emperor 361–363), restricted the granting of passes to the praetorian prefects and himself.[100] This was unworkable. He granted twelve to vicars and two to governors, one for use within the province and the other for communication to the emperor. Four each were issued to the three proconsuls of Asia, Africa and Achaea. The counts of the Treasury and Crown Estates could obtain warrants whenever they needs since these two departments supplied revenue in gold and the private income of the emperors respectively, matters of the greatest importance. The highest-ranking generals and frontier generals were issued passes, especially those at danger points like Mesopotamia.[101]

Fate

[edit]Notwithstanding its enormous costs, in the Eastern Roman Empire the service was still fully functioning in the first half of the sixth century, when the historian Procopius charges Emperor Justinian with the dismantlement of most of its sections, with the exception of the route leading to the Persian border (Secret History 30.1–11). The dromos continued to exist throughout the Byzantine period, supervised for much of it by the logothetēs tou dromou, although this post is not attested before the mid-eighth century and a revival of the service may then have occurred after a substantial gap. It was by then a much reduced service, restricted essentially to the remains of the old oxys dromos. The logothetes ton agelon, the overseer of the herds, was also an important figure as he provided many horses and other pack animals from the stud ranches (metada) of Asia and Phrygia.[102] By the eleventh century, the upkeep of the dromos had become duty of local peasants, similar to military units in active service.[102] These producers who contributed to the maintenance were inscribed in a special category in the fiscal register, freed from other state burdens, and were called exkoussatoi dromou.[103]

In the west, it survived under the Ostrogoths in Italy,[104] as Cassiodorus reports Theodoric the Great's correspondence.[105][106]

See also

[edit]- Agentes in rebus

- Barid (caliphate)

- Kaiserliche Reichspost

- Pony Express

- Jublains archeological site, an outpost of this network

References

[edit]- ^ Bianchetti, Cataudella & Gehrke 2015, p. 234.

- ^ Jongman 2003, p. 324.

- ^ Kolb 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Kolb 2015, p. 661-663.

- ^ Bond 2017, p. 55-56.

- ^ Hinson 2021, p. 280.

- ^ Jones 1964, pp. 830–834.

- ^ Bagrow 1964.

- ^ Erdkamp 2021, p. 163-164.

- ^ Collar & Kristensen 2020, p. 70.

- ^ Brent 2015, p. 247.

- ^ Belke 2017, p. 35-36.

- ^ Grig & Kelly 2012, p. 316-319.

- ^ Wells 1923, p. 15-16.

- ^ Peachin 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Sheldon 2004, p. 146.

- ^ Louth 2022.

- ^ Allen & Neil 2020, p. 96.

- ^ Crooks & Parsons 2016, p. 189.

- ^ Gill & Gempf 2000, p. 21.

- ^ Niewohner 2017.

- ^ Tschen-Emmons 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Tilburg 2007.

- ^ Matthews 2006, p. 67.

- ^ Traianus.

- ^ Allen, Neil & Mayer 2009, p. 72.

- ^ Willmore 2002, p. 91.

- ^ Wickham 2006, p. 128.

- ^ a b Jeffreys, Haldon & Cormack 2008, p. 302.

- ^ Belke 2012, p. 302-303.

- ^ Sheldon 2004, p. 144-146.

- ^ Ermatinger 2018, p. 94.

- ^ Arblaster 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Salway 2012, p. 316.

- ^ Fulford 2017, p. 315.

- ^ Tomas 2016, p. 96.

- ^ Adams & Laurence 2012.

- ^ Crowdy 2011, p. 38.

- ^ Krebs & Krebs 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Kolb 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Mitchell 2014, p. 246-261.

- ^ Westfahl 2015, p. 269.

- ^ Berger 2002, p. 422.

- ^ Kolb 2001, p. 380.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2014, p. 201.

- ^ Bagnall 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Sheldon 2004, p. 143.

- ^ Matyszak 2017.

- ^ Silverstein 2007, p. 30-31.

- ^ Nicholson 2018, p. 141.

- ^ Tranquillus 1913, p. 203-205.

- ^ a b Beale 2019.

- ^ Mellor 2012, p. 404.

- ^ Tranquillus 1913, p. 49.

- ^ Erdkamp 2010, p. 329.

- ^ Hezser 2011, p. 79.

- ^ a b Birley 2012.

- ^ Adams 2013, p. 66.

- ^ Kolb 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Stanković 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Bekker-Nielsen 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Bergh 2010, p. 447-448.

- ^ Berloquin 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Sabin, Wees & Whitby 2006, p. 404.

- ^ Hendy 2008, p. 603.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 313.

- ^ Sessa 2018, p. 154-155.

- ^ Adams & Laurence 2012, p. 95-105.

- ^ Argüín 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Tschen-Emmons 2014, p. 29.

- ^ Bekker-Nielsen 2004, p. 77-79.

- ^ MacKay 2012, p. 1-2.

- ^ Hezser 2011, p. 54-58.

- ^ Gosch & Stearns 2007, p. 35-38.

- ^ Thucydides et al. 2021.

- ^ Shepherd 2019, p. 304.

- ^ Winspear & Geweke 1935, p. 165.

- ^ Sarri 2017.

- ^ Yamauchi & Wilson 2022.

- ^ Tacitus, p. 73.

- ^ Petit 2022, p. 65.

- ^ Sartorio & Ventre 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Tappy 2012, p. 43.

- ^ Nankov 2022, p. 103.

- ^ Bergh 2011, p. 22-23.

- ^ Sarris 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Luttwak 2011, p. 109-110.

- ^ Bachrach 2013, p. 21.

- ^ Sheldon 2015, p. 11-12.

- ^ Rankov 2012, p. 1.

- ^ LePree & Djukic 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Williamson 2007.

- ^ Ramsey 1925, p. 60-74.

- ^ Plutarch.

- ^ Ferrero 1909, p. 287-288.

- ^ Eliot 1955, pp. 76–80.

- ^ Sotinel 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Claytor 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Bunson 2002.

- ^ Kelly 2006.

- ^ Jones 1964, pp. 130, 402.

- ^ a b Haldon 2005.

- ^ Kazhdan & Epstein 1990, p. 19.

- ^ Classen 2015.

- ^ Rousseau 2012.

- ^ Cassiodorus 2018, p. 131.

Bibliography

[edit]- Belke, Klaus (November 21, 2012). "Communications: Roads, and Bridges". The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- Belke, Klaus (2017-04-14). "Transport and Communication". The Archaeology of Byzantine Anatolia. pp. 28–38. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190610463.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-061046-3.

- Bond, Sarah E. (2017-12-07). "The Corrupting Sea: Law, Violence and Compulsory Professions in Late Antiquity". Trade, Commerce, and the State in the Roman World. Vol. 1. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198809975.003.0004.

- Claytor, W. Graham (2012-10-26), "Inn", in Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. wbeah22174, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah22174, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6, retrieved 2022-09-01

- Ferrero, Guglielmo (1909), The republic of Augustus, G. P. Putnam's Sons

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Fulford, Michael (2017-11-09). "Procurators' Business? Gallo-Roman Sigillata in Britain in the Second and Third Centuries ad". Trade, Commerce, and the State in the Roman World. Vol. 1. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198790662.003.0010.

- Haldon, John (September 2005). Byzantium A History. History Press. ISBN 9780750956734. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Kolb, Anne (2015), "Communications and Mobility in the Roman Empire", in Bruun, Christer; Edmondson, Jonathan (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336467.013.030, ISBN 9780195336467

- Kazhdan, A. P.; Epstein, Ann Wharton (February 1990). Change in Byzantine Culture in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520069626. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Matthews, John (2006-10-19). "Interlude: Travel and Topography". The Journey of Theophanes. pp. 62–88. doi:10.12987/yale/9780300108989.003.0004. ISBN 9780300108989.

- Mitchell, Stephen (2014-06-23). "Horse-Breeding for the Cursus Publicus in the Later Roman Empire". Infrastruktur und Herrschaftsorganisation im Imperium Romanum (in German). De Gruyter (A). pp. 246–261. doi:10.1524/9783050094694.246. ISBN 978-3-05-009469-4.

- Salway, Benet (2012-04-03). "There but Not There Constantinople in the Itinerarium Burdigalense". Two Romes: Rome and Constantinople in Late Antiquity. pp. 293–324. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199739400.003.0013. ISBN 978-0-19-973940-0.

- Sessa, Kristina (2018-08-09). Daily Life in Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-58063-2.

- Sheldon, R. M. (2015-09-03). Espionage in the Ancient World: An Annotated Bibliography of Books and Articles in Western Languages. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1099-3.

- Silverstein, Adam J. (2007-06-21). Postal Systems in the Pre-Modern Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46408-6.

- Sotinel, Claire (2009-01-30), Rousseau, Philip (ed.), "Information and Political Power", A Companion to Late Antiquity (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 125–138, doi:10.1002/9781444306101.ch9, ISBN 978-1-4051-1980-1, retrieved 2022-09-02

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - Wells, Benjamin W. (1923). "Trade and Travel in the Roman Empire". The Classical Journal. 19 (1): 7–16. ISSN 0009-8353. JSTOR 3288849.

- Argüín, Adolfo Raúl Menéndez (2015-03-04), "Administration: Principate", in Le Bohec, Yann (ed.), The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–71, doi:10.1002/9781118318140.wbra0023, ISBN 978-1-118-31814-0, retrieved 2022-09-01

- Peachin, Michael (2012-10-26), "Rescriptum", in Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. wbeah13222, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah13222, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6, retrieved 2022-09-01

- Rankov, Boris (2012-10-26), "Agentes in rebus", in Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. wbeah19006, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah19006, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6, retrieved 2022-09-01

- Bekker-Nielsen, Tønnes (2018-12-31), "Roads, Roman Empire", in Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 1–5, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah18111.pub2, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6, retrieved 2022-09-01

- Arblaster, Paul (2008-06-05), "Postal Service, History of", in Donsbach, Wolfgang (ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. wbiecp086, doi:10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecp086, ISBN 978-1-4051-8640-7, retrieved 2022-09-01

- Kolb, Anne (2012-10-26), "Mansiones, mutationes", The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah18075, ISBN 9781444338386, retrieved 2022-09-01

- Kolb, Anne (2019), "Transport, Roman", The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Wiley Online Library, pp. 1–5

- MacKay, Camilla (2012-10-26), "Postal services", in Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. wbeah06255, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah06255, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6, retrieved 2022-09-01

- Bagrow, Leo (1964), History of cartography, R. A. Skelton, ISBN 9781412825184

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Adams, Geoffrey William (2013). Marcus Aurelius in the Historia Augusta and Beyond. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-7638-2.

- Birley, Anthony R. (2012-12-06). Marcus Aurelius: A Biography. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-69569-0.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2010-12-13). A Companion to the Roman Army. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3921-5.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2021-11-15). The Roman Army and the Economy. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-49437-4.

- Mellor, Ronald (2012-11-12). The Historians of Ancient Rome. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-75278-0.

- Bunson, Matthew (2002). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Infobase. ISBN 1438110278.

- Kelly, Christopher (2006). Ruling the later Roman Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674022447.

- Variae epistolae [The Letters of Cassiodorus (1886); S.J.B. Barnish Cassiodorus: Variae]. Translated by Thomas Hodgkin. Liverpool: University Press, 1992). 537. ISBN 0-85323-436-1.

Theoderic's state papers. Editio princeps by M. Accurius (1533)

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Eliot, C.W.J. (1955). "New Evidence for the Speed of the Roman Imperial Post". Phoenix. 9 (2). Classical Association of Canada: 76–80. doi:10.2307/1086706. JSTOR 1086706.

- Plutarch. Galba. Vol. 7 – via uchicago.edu.

- Ramsey, A.M. (1925). "The speed of the Roman Imperial Post". Journal of Roman Studies. 15 (1): 60–74. doi:10.2307/295601. JSTOR 295601. S2CID 159587084.

- Williamson, G. A., ed. (2007) [1966]. "XXX". Procopius | The Secret History. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Sarris, Peter. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140455281.

A readable and accessible English translation of the Anecdota

- Kolb, Anne (2001), Colin Adams; Ray Laurence (eds.), "Travel & Geography in the Roman Empire", Transport and communication in the Roman state, ISBN 0-415-23034-9

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - Tacitus. The Histories.

- Tranquillus, Suetonius (1913). "C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Divus Augustus, chapter 49". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- Nicholson, Oliver (2018-03-22), "Cursus Publicus", The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, retrieved 2022-08-31

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - Shepherd, William (2019-11-28). The Persian War in Herodotus and Other Ancient Voices. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-0864-6.

- Thucydides; Herodotus; Xenophon; Polybius; Plutarch; Strabo (2021-11-10). The Great Historians of the Ancient World (illustrated) In 3 vol. Vol. I: The History of the Peloponnesian War, The Histories by Herodotus, Anabasis,The Polity of the Athenians and the Lacedaemonians,The Histories of Polybius, Lives of the noble Grecians and Romans by Plutarch Lives,The Geography of Strabo. Strelbytskyy Multimedia Publishing.

- Hezser, Catherine (2011). Jewish Travel in Antiquity. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-150889-9.

- Gosch, Stephen; Stearns, Peter (2007-12-12). Premodern Travel in World History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-58370-6.

- Bekker-Nielsen, Tønnes (2004). The Roads of Ancient Cyprus. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-956-5.

- Petit, Paul (2022-08-19). Pax Romana. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-33358-1.

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2011-11-30). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05420-2.

- LePree, James Francis; Djukic, Ljudmila (2019-09-09). The Byzantine Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-5147-6.

- Louth, Andrew (2022-02-17). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-263815-1.

- Bachrach, Bernard (2013-03-27). Charlemagne's Early Campaigns (768-777): A Diplomatic and Military Analysis. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-24477-1.

- Crooks, Peter; Parsons, Timothy H. (2016-08-03). Empires and Bureaucracy in World History: From Late Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-72106-3.

- Classen, Albrecht (2015-08-31). Handbook of Medieval Culture. Volume 1 (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-038544-1.

- Cassiodorus (2018-09-20). The Letters of Cassiodorus. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-7340-2458-0.

- Sabin, Philip; Wees, Hans van; Whitby, Michael (2006). The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78274-6.

- Jones, A. H. M. (2014-06-17). The Decline of the Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87305-1.

- Jones, A.H.M. (1964). The Later Roman Empire. BRILL. ISBN 9789004163836.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - A Companion to Byzantine Italy. BRILL. 2021-02-01. ISBN 978-90-04-30770-4.

- Hendy, Michael F. (2008-10-30). Studies in the Byzantine Monetary Economy C.300-1450. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08852-7.

- Tappy, Ron E. (2012-03-01). "The Tabula Peutingeriana: Its Roadmap to Borderland Settlements in Iudaea-Palestina With Special Reference to Tel Zayit in the Late Roman Period". Near Eastern Archaeology. 75 (1): 36–55. doi:10.5615/neareastarch.75.1.0036. ISSN 1094-2076. S2CID 164145236.

- Hinson, Benjamin (2021-10-01). "Send Them to Me by This Little One: Child Letter-carriers in Coptic Texts from Late Antique and Early Islamic Egypt". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 80 (2): 275–289. doi:10.1086/715988. ISSN 0022-2968. S2CID 239028712.

- Bergh, Rena (2010-01-01). "A shared law". Fundamina: A Journal of Legal History. 16 (1): 443–458. hdl:10520/EJC34376.

- Willmore, Larry (2002). "Government policies toward information and communication technologies: a historical perspective". Journal of Information Science. 28 (2): 89–96. doi:10.1177/016555150202800201. ISSN 0165-5515. S2CID 20810832.

- Jongman, WM. (2003), "The Political Economy of a World-Empire", The Medieval History Journal, doi:10.1177/097194580300600208, S2CID 162564052

- Nankov, Emil (2022). "From utility to imperial propaganda: (Re)discovering a milestone of Constantine I from the vicinity of Bona Mansio and emporion Pistiros and its significance for the study of the 'Via Diagonalis' in the territory of Philippopolis". Българско е-Списание за Археология. 12 (1): 97–116. ISSN 1314-5088.

- Stanković, Emilija (2012). "Diocletian's Military Reforms". Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Legal Studies. 1 (1): 129–141. ISSN 2285-6293.

- Bergh, Rena Van Den (2011). "Communication and Publicity of the Law in Rome". Studia Universitatis Babes Bolyai - Iurisprudentia. 56 (1): 20–30. ISSN 2065-7498.

- Winspear, Alban Dewes; Geweke, Lenore Kramp (1935). Augustus and the reconstruction of Roman government and society. University of Wisconsin studies in the social sciences and history, no. 24. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin.

- Yamauchi, Edwin M.; Wilson, Marvin R. (2022-05-17). Dictionary of Daily Life in Biblical & Post-Biblical Antiquity: Communication & Messengers. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61970-421-3.

- Krebs, Robert E.; Krebs, Carolyn A. (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Ancient World. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31342-4.

- Bagnall, Roger S. (2006). Hellenistic and Roman Egypt: Sources and Approaches. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-5906-8.

- Westfahl, Gary (2015-04-21). A Day in a Working Life: 300 Trades and Professions through History [3 volumes]: 300 Trades and Professions through History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-403-2.

- Matyszak, Philip (2017-10-05). 24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There. Michael O'Mara Books. ISBN 978-1-78243-857-1.

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A. (2014-05-14). Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7482-2.

- Gill, David W.; Gempf, Conrad (2000-11-24). The Book of Acts in its First Century Setting, Volume 2: Graeco-Roman Setting. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57910-526-6.

- Wickham, Chris (2006-11-30). Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400-800. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-162263-2.

- Jeffreys, Elizabeth; Haldon, John F.; Cormack, Robin (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925246-6.

- Allen, Pauline; Neil, Bronwen; Mayer, Wendy (2009). Preaching Poverty in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Realities. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt. ISBN 978-3-374-02728-6.

- Tomas, Agnieszka (2016-07-10). Inter Moesos et Thraces: The Rural Hinterland of Novae in Lower Moesia (1st – 6th Centuries AD). Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78491-370-0.

- Sarri, Antonia (2017-11-20). Material Aspects of Letter Writing in the Graeco-Roman World: c. 500 BC – c. AD 300. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-042348-8.

- Crowdy, Terry (2011-12-20). The Enemy Within: A History of Spies, Spymasters and Espionage. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-243-6.

- Ermatinger, James W. (2018-05-01). The Roman Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3809-5.

- Berloquin, Pierre (2008). Hidden Codes & Grand Designs: Secret Languages from Ancient Times to Modern Day. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4027-2833-4.

- Rousseau, Philip (2012-01-25). A Companion to Late Antiquity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-29347-8.

- Grig, Lucy; Kelly, Gavin (2012-03-07). Two Romes: Rome and Constantinople in Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992118-8.

- Tschen-Emmons, James B. (2014-09-30). Artifacts from Ancient Rome. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-620-3.

- Niewohner, Philipp (2017-03-17). The Archaeology of Byzantine Anatolia: From the End of Late Antiquity until the Coming of the Turks. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-066262-2.

- Allen, Pauline; Neil, Bronwen (2020-09-10). Greek and Latin Letters in Late Antiquity: The Christianisation of a Literary Form. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-91645-5.

- Beale, Philip (2019-06-04). A History of the Post in England from the Romans to the Stuarts. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-64838-0.

- Brent, Revd Allen (2015-12-22). The Imperial Cult and the Development of Church Order: Concepts and Images of Authority in Paganism and Early Christianity before the Age of Cyprian. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-31312-5.

- Sartorio, Giuseppina Pisani; Ventre, Francesca (2004). The Appian Way: From Its Foundation to the Middle Ages. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-752-8.

- Bianchetti, Serena; Cataudella, Michele; Gehrke, Hans-Joachim (2015-11-24). Brill's Companion to Ancient Geography: The Inhabited World in Greek and Roman Tradition. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-28471-5.

- Berger, Adolf (2002). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-58477-142-5.

- Collar, Anna; Kristensen, Troels Myrup (2020-07-13). Pilgrimage and Economy in the Ancient Mediterranean. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-42869-0.

- Adams, Colin; Laurence, Ray (2012-12-06). Travel and Geography in the Roman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-58180-1.

- Sheldon, Rose Mary (2004-12-16). Intelligence Activities in Ancient Rome: Trust in the Gods but Verify. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-77106-5.

- Tilburg, Cornelis van (2007-01-24). Traffic and Congestion in the Roman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-12974-4.

- Sarris, Peter (2012). "Byzantium, political structure". In Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew; Huebner, Sabine R (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Ancient History (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah03033. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5.

- Traianus, Caesar, Trajan to Pliny X 46,

Diplomata, quorum praeteritus est dies, non debent esse in usu. Ideo inter prima iniungo mihi, ut per omnes provincias ante mittam nova diplomata, quam desiderari possint.