Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pannonia

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2016) |

Pannonia (/pəˈnoʊniə/, Latin: [panˈnɔnia]) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, on the west by Noricum and upper Italy, and on the south by Dalmatia and upper Moesia. It included the modern regions of western Hungary, western Slovakia, eastern Austria, northern Croatia, north-western Serbia, northern Slovenia, and northern Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Key Information

Background

[edit]In the Early Iron Age, Transdanubia was inhabited by the Pannonians or Pannonii,[note 1] a collection of Illyrian tribes. The Celts invaded the region during the Late Iron Age, and Gallo-Roman historian Pompeius Trogus wrote that they faced heavy resistance from the locals, which eventually prevented them from overrunning the southern part of Transdanubia. Some tribes advanced as far as Delphi, with the Scordisci settling in Syrmia (279 BC) upon being forced to withdraw.[8] Additionally, the arrival of the Celts in Transdanubia disrupted the flow of amber from the Baltic Sea region, through the Amber Road, to the Illyrians.[9] They founded many villages. Those that held prominent economic significance developed into oppida.[8] Independent tribes minted their own coins with the faces of their leaders. These were at first modelled on Macedonian and, later, Roman currency.[10]

Upon the Scordisci's withdrawal and settlement, they and the Dardani (in Dardania) both became strong powers that opposed each other. The Dardani consistently raided Macedon and developed close ties to Rome.[11] Philip V, who was a vehement enemy of the Dardani, allied with the Scordisci and, in 179 BC, persuaded the Bastarnae (at the Danube Delta) to break into Italy and subdue them on the way. Despite Philip's defeat at the hands of the Romans in 197 BC and the failure of the Bastarnae, at this time the Dardani's power crumbled under the pressure from the Macedonians and Scordisci. Finally, Perseus annihilated them, giving way to a hundred years of Scordisci hegemony in the Balkans. During this time, the tribe started raiding the new province of Macedonia, and —Strabo says— expanded as far as Paeonia, Illyria, and Thrace.[12]

Aquileia's foundation in 181 BC was the first step towards the Roman takeover of Pannonia. The town served as the starting station of the Amber Road and the launching point for attacks in that direction.[13] The Scordisci, in alliance with the Dalmatae, were in armed conflict with the Romans as early as 156 BC and 119 BC. In both wars, the Romans failed to conquer Siscia (now Sisak, Croatia), which laid in a key position.[14] After these setbacks, Rome turned its attention to Noricum, which had both iron and silver mines.[15]

As part of a new Celtic migration wave at the end of the 2nd century BC, the Boii left Northern Italy and established themselves as a significant power on the Danube.[16] According to Posidonius's record of the Cimbri migration (preserved by Strabo), they were first repulsed by the Boii, then by the Scordisci, and then by the Taurisci towards the Helvetii. This describes the balance of power in the region.[17] In the early 1st century BC, the Dacians emerged as a new dominant power. While their hold on the area between the Danube and the Tisza river was loose, they had considerable influence in the territories beyond.[18] In 88 BC, Scipio Asiaticus (consul 83 BC) defeated the Scordisci so badly that they retreated to the eastern part of Syrmia.[19] Taking advantage of this situation, the Dacian king Burebista vanquished them sometime between 65 and 50 BC, and subsequently the Boii[note 2] and the Taurisci too. Thanks to the ebb of these entities, several local tribes regained their independence and influence.[21] In the context of Mithridates VI Eupator's unfulfilled plan to invade Italy from the north (64 BC), the territory he was to cross is noted to have belonged to the Pannonians.[22] Immediately after Burebista's death (c. 44 BC), Dacia's kingdom dissolved too,[20] leaving no entity in the region that Rome would make allowances for.[23]

Roman conquest

[edit]

The Pannonians were driven into conflict due to their support of the Dalmatae in their strife against Rome,[7] but they weren't long-term and known enemies.[24] The tribes north of the Drava River didn't participate in this, nor in the subsequent fights.[15] In 35 BC, Octavian led a campaign against the Iapydes and the Pannonians,[25] in which he captured Siscia in a month-long siege[26] and occupied a large part of the Sava River valley. This was in accordance with Caesar's plan of creating a base for an invasion of Dacia, not realized due to his assassination. However, Octavian only used the hoax of the "Dacian threat" as a pretense to gain control over a large amount of land in the Second Triumvirate.[27]

In 15 BC, the future emperor Tiberius defeated the Scordisci, forcing them to become allies. This was in response to Pannonian and Scordisci incursions the previous year.[28] The following events were part of the Roman Empire's efforts to reach the Danube[29] and are sometimes known thematically as Bellum Pannonicum.[30]

In 14 BC, the Pannonians rose up. Vipsanius Agrippa was sent to the region after another rebellion in 13 BC. After his death the following year, the campaign was taken over by Tiberius,[31] who celebrated his triumph in 11 BC. The province of Illyricum was established between the Sava and the Adriatic Sea.[32] In 10 BC, Tiberius returned to quell a new uprising of the Pannonians and Dalmatae.[33] After winning in 9 BC, he sold the youth of the Breuci and Amantini as slaves in Italy[34] and held an ovation.[33] His operations between 12 and 9 BC included constant expeditions into territories north of the Drava and almost certainly brought the whole Transdanubia under Roman control, even though there's no direct evidence for that.[35]

Through Tiberius Nero, then my stepson and legate, I brought under Roman authority the Pannonian peoples, which no Roman army had approached before I became princeps and advanced the boundaries of Illyricum to the bank of the Danube.

— Augustus, Res Gestae Divi Augusti, chapter 30[36]

Pannonia was invaded by the Dacians in 10 BC. The Romans launched campaigns through the Danube in order to secure it as the imperial border and defend the threatened new land. Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus's (consul 16 BC) operation in 1 AD extended as far as the Elbe. In 10 AD, Cornelius Lentulus Augur was able to debar not just the Dacians, but also the Sarmatians "from access to the Danube", says Florus. Locally more important was the offensive of Marcus Vinicius against the tribes east of the Danube Bend, showing an intent of "monopolizing" the Northern Transdanubian region politically. The last decade of the century saw the Marcomanni under their king Maroboduus, settling north of Pannonia.[37] Augustus planned a two-sided attack on them, with one army approaching their territory from the Rhine and another one under Tiberius crossing the Danube at Carnuntum.[38]

Before witnessing any result, Tiberius had to rush back in 6 AD and face a new uprising.[39][note 3] The unfolding Bellum Batonianum lasted for three years. The Breuci (under Bato the Breucian) and Daesitiates (under Bato the Daesitiate and Pinnes) took the leading role, while the tribes north of the Drava stayed out again. The insurgents attempted to invade Italy and Macedonia, but due to their lack of success, they united to besiege Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia). There, Caecina Severus defeated the insurgents, who retreated into the Fruška gora Mountains.[41] He annihilated them the following year when they tried to intercept him on his way to join Tiberius at Siscia.[42] Tiberius competently initiated a scorched-earth policy[43] which was unsatisfactory for Augustus, who sent more generals, including Germanicus and Plautius Silvanus (consul 2 BC) to the war theatre.[44] A capitulation was forced out in 8 AD, and Bato the Breucian delivered Pinnes to the Romans, becoming a vassal king of his tribe. However, the revolt flared up once again as the Daesitiates captured and executed Bato the Breucian and persuaded his people to continue the resistance.[45] Silvanus reconquered them and ousted Bato the Daesitiate into the Dinaric Alps, where he laid down arms in 9 AD.[46]

History

[edit]Consolidation and establishment of administration

[edit]Illyricum was divided into Dalmatia (initially called Illyricum Superius) and Pannonia (initially Illyricum Inferius) in 8 or 9 AD.[note 4][47]

According to Suetonius, with the Bellum Batonianum, Tiberius finally defeated all peoples between the Danube and the Adriatic Sea.[7] No Illyrian resistance is known after this, not due to the natives' compliance with the new status quo, but due to their extreme exhaustion.[48] The eligible Pannonian youth were conscripted and commanded to other provinces.[49] The communities taking part in the uprising were afterward relocated and organized into civitates under military supervision.[note 5][33]

The military occupation of Pannonia may have been carried out in gradual steps.[15] The Romans felt it necessary to resettle certain tribes to the territory of the peoples north of the Drava, which, for them, had no economic, but strategic significance. Augustus formed a kind of alliance where the Romans would act as supervisors, and it was not until his death (14 AD) that legions would be moved over from South Pannonia.[50]

The second emperor Tiberius (r. 17 – 37 AD) founded multiple coloniae in the province and developed its road network.[51] However, due to these land's unsuitability for cultivation, it was a hard task to persuade veterans to comply with settling there, and he had to silence a mutiny right when assuming power.[52] He sent his son Drusus Julius Caesar to create tranquility and depose Maroboduus, who needed Roman support for his war against Arminius. This ultimately caused the rise of Vannius (20 AD), who ruled over an extended realm.[53]

It was Claudius (r. 41 – 54 AD) who finished Pannonia's occupation and began to construct of the local limes. Systematic integration into the Empire accompanied by the establishment of settled Roman life progressed subsequently.[54] In 50 AD, Vannius was overthrown by Vangio and Sido, who enjoyed the emperor's support.[55] By this date, the nomadic Sarmatian population of the Iazyges had taken possession of the Danube–Tisza Interfluve, helping the Romans by being a buffer state against the dangerous Dacians.[56]

At first, the primary goal of the Roman administration was the conclusion of the barbarian conflicts outside the province. In Nero's time (r. 54 – 68 AD) as many as 100,000 barbarians were moved from Pannonia to Moesia by Plautius Silvanus Aelianus, and 50,000 may have been settled in Pannonia by Tampius Flavianus. During his important governorship, money began to circulate in the Barbaricum and the line of the limes was stabilized.[54]

Under the Flavians

[edit]The Year of the Four Emperors (69 AD) passed with peace in Pannonia. Flavianus declared for Vespasian and led his legions to Italy against Vitellius.[57] Vespasian (r. 69 – 79 AD) invested greatly in the construction of the limes.[54] Discarding the Augustan strategy where the legions' role was with maintaining order in their provinces, the Flavian emperors continually moved them to the border. This way they were prevented from interfering in domestic policy, while the conquests were already pacified.[58] Systematic circulation of money in the region situated north of the Drava shows that by this time Roman civilization had firmly taken root there.[54]

Domitian's (r. 81–96) emperorship saw expensive wars with the barbarians, as a result of which the military emphasis shifted to the Danube frontier.[59] At the end of 85 or the beginning of 86, the reemerging Dacians under Decebalus raided Moesia, killing its governor and eradicating a legion. After a brief stay, Domitian left Cornelius Fuscus to deal with the situation. After clearing the province of raiders, Fuscus undertook a disastrous campaign and lost his life (86). Finally, in 88, Tettius Julianus defeated Decebalus and the sides agreed to make peace.[60] Vangio and Sido were most likely dead by now, the Marcomanni and Quadi denied vassal duties.[61] When the emperor's punitive expedition (partially sent through Dacian territory) was repelled in 89, he—despite the damages suffered—settled for mild terms with Decebalus, instead committing his forces elsewhere. In the same year, he held his triumphs over the Dacians and Chatti, but not over the disloyal Danubian Germans. When the Romans started supporting the Lugii against them, they made a pact with the Iazyges. This produced another war, almost completely unknown except for another catastrophe and destruction of a legion at the hands of the nomads.[62] In 92 or 93, he finished the war, but held only an ovation, indicating he probably had further plans in Pannonia.[63]

Under the Antonines

[edit]We hear of war with the Danubian Germans again under Nerva (r. 96–98).[64]

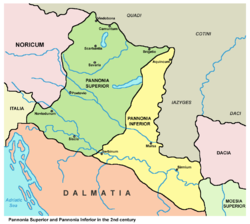

Between 103 and 107, Trajan (r. 98–117) executed the division of the province into Pannonia Inferior and Pannonia Superior. This allowed the Empire to better combat the radically different Germanic and Sarmatian tribes.[65] While Superior had most urbanized areas and a shorter frontier with three legions, Inferior contained one municipium and one legion, virtually being a border zone.[66] Under his reign, the placement of garrison and the main lines of commerce became permanent.[67]

The creation of Roman Dacia had a great effect on Pannonia. In Trajan's Dacian Wars, the Iazyges allied with the Romans, seeking to retain Oltenia where they were expelled by Decebalus. A brief confrontation in 107 was resolved Hadrian, then-governor of Pannonia Inferior and it may have been agreed that the nomads would instead take possession of the region between the Tisza and the Apuseni Mountains, not incorporated into the new province.[68] However, taking advantage of Trajan's death and the preoccupation of the Empire with the Parthian war, they joined forces with the relative Roxolani and attacked again in 117, to which Dacia's governor, Julius Quadratus Bassus fell victim. Hadrian (r. 117–138) traveled to the spot and invested Marcius Turbo as governor of both Dacia and Pannonia Inferior to defeat the barbarians. The Roxolani were pacified first. Turbo's authorization was over in 119 as Iazyx peace envoys appeared in Rome.[69] The postal connection between the two provinces through the Danube–Tisza Interfluve—which aggravated relations with the Sarmatians—was completed.[70]

War with the Quadi broke out again in the last years of Hadrian's reign, which his adopted son and joint governor of the Pannonian provinces, Aelius Caesar successfully handled until he died in 138. Command of Pannonia Superior was taken over by Haterius Nepos, who ended the war with a Roman victory, becoming the last person to be awarded with ornamenta triumphalia.[71]

Under Antoninus Pius's (r. 138–161) quiet reign, some coins were issued propagating not the ending of a new campaign but the reestablishment of foederatus relationship by the investiture of a new Quadi king. Discharges and detachments of troops happened.[72]

Findings of hoards of coins likely buried during the rule of Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180) evidence turmoil due to barbarian attacks.[73] Large-scale population movements in Northern and Eastern Europe related to the Goths highly endangered Rome's clients, who wanted the Empire to give its lands to settlement and extend its protection over the tribes. Rome was unwilling to grant these requests.[74] The Romans may not have been aware of the dangerous situation at the start of the Parthian war of Lucius Verus because they sent a whole legion and many vexillationes away from Pannonia. It is thanks to the diplomatic efforts made by regional governors that tensions were eased until the dispatched forces could get back. When the threat became fully clear, Marcus even raised new legions.[75] The first attack came in the winter of 166-167, from the Lombards and Ubii, between Brigetio and Arrabona. It was quickly repulsed by two auxiliary units. Cassius Dio tells of a legation of 11 tribes led by the Marcomanni subsequently petitioning the governor of Pannonia Superior, Iallius Bassus to concede. This may have been the last attempt at making peace, as next, a barbarian coalition formed to fight Rome.[76]

In 168, Marcus and Verus returned to Aquileia and set up their base there. The Marcomanni and Quadi broke through the border and the Alps' crosses, besieging the city and burning the small town of Opitergium. The peak of the Antonine Plague in the peninsula was at this time, causing Verus's death. The next years' heavy fighting resulted in the death of governor of Moesia Superior and Dacia Claudius Fronto and praetorian prefect Macrinius Vindex. Claudius Pompeianus and future-emperor Pertinax returned part of the spoils taken by the enemy and led the offensive starting from 172. Against severe losses, the Romans forced first the Quadi, then the Marcomanni to surrender (172–173), while the military emphasis shifted to the Iazyges. Despite the winter incursion of the Iazyges was crushed (173-174), the Quadi overthrew their Roman-installed king and started to support the nomads. While the two nations tried to negotiate, Marcus eventually defeated both of them in separate campaigns.[77]

The second phase of the war started in 177. The attacking barbarians were kept in check, with Marcus and his son, the newly acclaimed Commodus (r. 177–192) coming to Pannonia. A decisive campaign by Tarrutenius Paternus in 179 convinced the Iazyges to make peace. In the same year, the land of the Danubian Germans was occupied by a force Cassius Dio claims to be 40,000 men—the number of soldiers stationed in Pannonia Inferior and Pannonia Superior combined. Control over tribes was taken over by prefects. Valerius Maximianus, born in Pannonia, was an important general here.[78] Any possible plans with the creation of two new provinces—Marcomannia and Sarmatia—were aborted after the death of Marcus in 180. Commodus returned to the old border and client system, to which new residents were seemingly willing to join. As the barbarians pillaged during the war, taking cattle and captives away en masse, the destruction and loss of life in Pannonia was huge.[79]

Commodus vigorously started to strengthen the limes with new fortifications. Minor raids on the province continued to occur, prompting a third campaign over the Danube at about. This campaign was smaller, and its leader, Tigidius Perennis, achieved a victory. Another victorious expedition was conducted in 188.[80]

Under the Severans

[edit]During the Year of the Five Emperors (193), no attack was made on Pannonia. According to Herodian, Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) calmed the barbarian tribes via negotiations before marching off his troops to Italy and gaining the throne. In the coming years, the arrival of foreign groups led to new conflicts, but these were centered on Dacia and Pannonia only experienced collateral effects.[81] The Severans' rule was supported by the Pannonian military and other provinces of the collective "Illyricum" region, which became politically important.[82] In 202, a thorough visit to Pannonia by the imperial house was organized. Partly during this tour and throughout Severus' reign, the province benefited from many constructions. The road network was fully repaired, civilian and military buildings were inaugurated, military camps were improved and cities were protected with walls thus increasing their rank.[83]

Administration

[edit]Pannonia Superior was under the consular legate, who had formerly administered the single province, and had three legions under his control. Pannonia Inferior was at first under a praetorian legate with a single legion as the garrison; after Marcus Aurelius, it was under a consular legate, but still with only one legion. The frontier on the Danube was protected by the establishment of the two colonies Aelia Mursia and Aelia Aquincum by Hadrian.

Under Diocletian and his successors, a fourfold division of the country was made:[84]

- Pannonia Prima in the northwest, with its capital in Savaria, it included Pannonia Superior and the major part of Central Pannonia between the Raba and Drava,

- Pannonia Valeria in the northeast, with its capital in Sopianae, it comprised the remainder of Central Pannonia between the Raba, Drava and Danube,

- Pannonia Savia in the southwest, with its capital in Siscia,

- Pannonia Secunda in the southeast, with its capital in Sirmium

Diocletian also moved parts of today's Slovenia out of Pannonia and incorporated them in Noricum.[85] In 324 AD, Constantine I enlarged the borders of Roman Pannonia to the east, annexing the plains of what is now eastern Hungary, northern Serbia and western Romania up to the limes that he created: the Devil's Dykes.[citation needed]

In the 4th–5th century, one of the dioceses of the Roman Empire was known as the Diocese of Pannonia. It had its capital in Sirmium and included all four provinces that were formed from historical Pannonia, as well as the provinces of Dalmatia, Noricum Mediterraneum and Noricum Ripense.[86]

-

Pannonia in the 1st century

-

Pannonia in the 2nd century

-

Pannonia in the 4th century

-

Pannonia with Constantine I "limes" in 330 AD

Loss

[edit]In the 4th century, the Romans (especially under Valentinian I) fortified the villas and relocated barbarians to the border regions. In 358 they won a great victory over the Sarmatians, but raids didn't stop. In 401 the Visigoths fled to the province from the Huns, and the border guarding peoples fled to Italia from them, but were beaten by Uldin in exchange for the transferring of Eastern Pannonia. In 433 Rome completely handed over the territory to Attila for the subjugation of the Burgundians attacking Gaul.[87]

After Roman rule

[edit]

During the Migration Period in the 5th century, some parts of Pannonia were ceded to the Huns in 433 by Flavius Aetius, the magister militum of the Western Roman Empire.[88] After the collapse of the Hunnic empire in 454, large numbers of Ostrogoths were settled by Emperor Marcian in the province as foederati. The Eastern Roman Empire controlled southern parts of Pannonia in the 6th century, during the reign of Justinian I. The Byzantine province of Pannonia with its capital at Sirmium was temporarily restored, but it included only a small southeastern part of historical Pannonia.

Afterwards, it was again invaded by the Avars in the 560s, and the Slavs, who first may settled c. 480s but became independent only from the 7th century. In 790s, it was invaded by the Franks, who used the name "Pannonia" to designate the newly formed frontier province, the March of Pannonia. The term Pannonia was also used for Slavic polity like Lower Pannonia that was vassal to the Frankish Empire.

Through Roman influence, a dialect of Latin now called Pannonian Latin developed in the region; the several major political shifts would see it extinct around the 6th century.[89]

Cities and auxiliary forts

[edit]

The native settlements consisted of pagi (cantons) containing a number of vici (villages), the majority of the large towns being of Roman origin. The cities and towns in Pannonia were:

Now in Austria:

Now in Bosnia and Herzegovina:

Now in Croatia:

- Ad Novas (Zmajevac)

- Andautonia (Ščitarjevo)

- Aqua Viva (Petrijanec)

- Aquae Balisae (Daruvar)

- Certissa (Đakovo)

- Cibalae (Vinkovci)

- Cornacum (Sotin)

- Cuccium (Ilok)

- Halicanum (Sveti Martin na Muri)

- Iovia or Iovia Botivo (Ludbreg)

- Marsonia (Slavonski Brod)

- Mursa (Osijek)

- Siscia (Sisak)

- Teutoburgium (Dalj)

Now in Hungary:

- Ad Flexum (Mosonmagyaróvár)

- Ad Mures (Ács)

- Ad Statuas (Vaspuszta)

- Ad Statuas (Várdomb)

- Alisca (Szekszárd)

- Alta Ripa (Tolna)

- Aquincum (Óbuda, Budapest)

- Arrabona (Győr)

- Brigetio (Szőny)

- Caesariana (Baláca)

- Campona (Nagytétény)

- Cirpi (Dunabogdány)

- Contra-Aquincum (Budapest)

- Contra Constantiam (Dunakeszi)

- Gorsium-Herculia (Tác)

- Intercisa (Dunaújváros)

- Iovia (Szakcs)

- Lugio (Dunaszekcső)

- Lussonium (Dunakömlőd)

- Matrica (Százhalombatta)

- Morgentianae (Tüskevár (?))

- Mursella (Mórichida)

- Quadrata (Lébény)

- Sala (Zalalövő)

- Savaria (Szombathely)

- Scarbantia (Sopron)

- Solva (Esztergom)

- Sopianae (Pécs)

- Ulcisia Castra (Szentendre)

- Valcum (Fenékpuszta)

Now in Serbia:

- Acumincum (Stari Slankamen)

- Ad Herculae (Čortanovci)

- Bassianae (Donji Petrovci)

- Bononia (Banoštor)

- Burgenae (Novi Banovci)

- Cusum (Petrovaradin)

- Graio (Sremska Rača)

- Onagrinum (Begeč)

- Rittium (Surduk)

- Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica)

- Taurunum (Zemun)

Now in Slovakia:

Now in Slovenia:

Economy

[edit]The country was fairly productive, especially after the great forests had been cleared by Probus and Galerius. Before that time, timber had been one of its most important exports. Its chief agricultural products were oats and barley, from which the inhabitants brewed a kind of beer named sabaea. Vines and olive trees were little cultivated. Pannonia was also famous for its breed of hunting dogs. Although no mention is made of its mineral wealth by the ancients, it is probable that it contained iron and silver mines.

Slavery

[edit]Slavery held a less important role in Pannonia's economy than in earlier established provinces. Rich civilians had domestic slaves do the housework while soldiers who had been awarded with land had their slaves cultivate it. Slaves worked in workshops primarily in western cities for rich industrialist.[90] In Aquincum, they were freed in a short time.[91]

Religion

[edit]Pannonia had sanctuaries for Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, official deities of empire, and also for old Celtic deities. In Aquincum there was one for the mother goddess. The imperial cult was also present. In addition, Judaism and eastern mystery cults also appeared, the latter centered around Mithra, Isis, Anubis and Serapis.[91]

Christianity began to spread inside the province in the 2nd century. Its popularity didn't decrease even during the big persecutions in the late 3rd century. In the 4th century, basilicas and funeral chapels were built. We know of the Church of Saint Quirinus in Savaria and numerous early Christian memorials from Aquincum, Sopianae, Fenékpuszta, and Arian Christian ones from Csopak.[91]

Legacy

[edit]The ancient name Pannonia is retained in the modern term Pannonian plain.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Whose name the toponym "Pannonia" stems from.[7]

- ^ Hence the name deserta Boiorum ('desert of the Boii') used even by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History.[20]

- ^ Which was motivated by an order of conscription (from governor Valerius Messala Messallinus) among the tribesmen, according to Cassius Dio.[40]

- ^ It was not until the second part of the century that the term "Pannonia" came into common usage.

- ^ The Azali were moved northwards at this time.

References

[edit]- ^ Haywood, Anthony; Sieg, Caroline (2010). Lonely Planet Vienna. Lonely Planet. p. 21. ISBN 9781741790023.

- ^ Goodrich, Samuel Griswold (1835). "The third book of history: containing ancient history in connection with ancient geography". p. 111.

- ^ Lengyel, Alfonz; Radan, George T.; Barkóczi, László (1980). The Archaeology of Roman Pannonia. University Press of Kentucky. p. 247. ISBN 9789630518864.

- ^ Laszlovszky, J¢Zsef; Szab¢, Péter (2003). People and nature in historical perspective. Central European University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9789639241862.

- ^ "Historical outlook: a journal for readers, students and teachers of history, Том 9". American Historical Association, National Board for Historical Service, National Council for the Social Studies, McKinley Publishing Company. 1918. p. 194.

- ^ Pierce, Edward M., ed. (1869). "THE COTTAGE CYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY". p. 915.

- ^ a b c Barkóczi 1980, p. 89.

- ^ a b Trogmayer 1980, p. 81.

- ^ Wilkes 1992, p. 225.

- ^ Trogmayer 1980, p. 81; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 29–31

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 12.

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 13-14, 15.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 90; Mócsy 1974a, p. 33

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 86; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 15, 16

- ^ a b c Barkóczi 1980, p. 90.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 86.

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 16.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 87.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Mócsy 1974a, p. 18; Tóth 1983, p. 19

- ^ a b Mócsy 1974a, p. 21.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 87; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 18, 19; Tóth 1983, p. 20

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 87; Mócsy 1974a, p. 18

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 22.

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 24.

- ^ Tóth 1983, p. 20.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 87; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 22–25

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Mócsy 1974a, p. 25; Tóth 1983, p. 20

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 26.

- ^ Džino, Danijel (2012). "Bellum Pannonicum: The Roman armies and indigenous communities in southern Pannonia 16-9 BC". In Hauser, Martin; Feodorov, Ioana; Sekunda, Nicholas V.; Dumitru, Adrian George (eds.). Actes du Symposium International: Le livre, la Roumanie, l'Europe. Vol. 3 (4th ed.). Bucharest: Editura Biblioteca Bucureştilor. p. 461.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Mócsy 1974a, p. 37; Tóth 1983, p. 20

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 38; Tóth 1983, p. 20

- ^ a b c Tóth 1983, p. 21.

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 37-38; Tóth 1983, p. 21; Wilkes 1992, p. 207

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 91; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 35, 38

- ^ Wilkes 1992, p. 206.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 39–40, 45

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Mócsy 1974a, p. 42

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974a, p. 42; Tóth 1983, p. 21

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 42.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 42–43

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974a, p. 43

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974a, p. 43; Tóth 1983, p. 21

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 43.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974a, p. 44; Tóth 1983, p. 21

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974a, p. 44

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974a, p. 44; Tóth 1983, p. 21

- ^ Wilkes 1992, p. 207-208.

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 44.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 91.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, pp. 91–92; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 45–46, 50

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 45-46.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 96; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 46–47

- ^ a b c d Barkóczi 1980, p. 92.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 90; Mócsy 1974a, p. 47

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 96; Mócsy 1974a, p. 41; Tóth 1983, p. 22

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, pp. 47, 48; Tóth 1983, p. 22

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 49, 85.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 93; Mócsy 1974a, p. 98

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 87.

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 88.

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 89.

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, pp. 89–90; Tóth 1983, p. 23

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 93; Mócsy 1974a, p. 90; Tóth 1983, p. 23

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 93; Mócsy 1974a, p. 98

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 99.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 94; Mócsy 1974a, p. 102

- ^ Mócsy 1974a, p. 103.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 94; Mócsy 1974a, p. 104; Tóth 1983, pp. 24–25

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 94; Mócsy 1974a, p. 104

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 95; Mócsy 1974a, p. 106; Tóth 1983, p. 25

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 95; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 106–107; Tóth 1983, p. 25

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 95; Mócsy 1974a, pp. 107–108

- ^ Mócsy 1974b, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 96; Mócsy 1974b, p. 7

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 97; Mócsy 1974b, pp. 10–12; Tóth 1983, p. 30

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, pp. 97–98; Mócsy 1974b, pp. 11–16

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 98; Mócsy 1974b, p. 17

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 99; Mócsy 1974b, pp. 18–22

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 99; Mócsy 1974b, p. 25; Tóth 1983, p. 27

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, pp. 100–101; Mócsy 1974b, p. 25

- ^ Mócsy 1974b, p. 29.

- ^ Barkóczi 1980, p. 102; Tóth 1983, p. 28

- ^ Borhy 2014, pp. 124–127.

- ^ Borhy 2014, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Fitz 1993–1995, pp. 1175–1177.

- ^ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 18.

- ^ Harvey, Bonnie C. (2003). Attila, the Hun – Google Knihy. Infobase. ISBN 0-7910-7221-5. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- ^ Gonda, Attila (June 2016). "Fehér Bence: Pannonia latin nyelvtörténete. Budapest 2007". Antik Tanulmányok - Studia Antiqua (in Hungarian). 60: 93–107. doi:10.1556/092.2016.60.1.7. ISSN 0003-567X.

- ^ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 14.

Sources

[edit]- Borhy, László (2014). Die Römer in Ungarn. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-8053-4820-1.

- Lengyel, Alfonz; Radan, George T., eds. (1980). The archaeology of Roman Pannonia (PDF). Lexington, Budapest: University Press of Kentucky, Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 0-8131-1370-9.

- Trogmayer, Ottó. "Pannonia before the Roman conquest". In Lengyel & Radan (1980).

- Barkóczi, László. "History of Pannonia". In Lengyel & Radan (1980).

- Mócsy, András (1974a). Harmatta, János (ed.). Pannónia a korai császárság idején [Pannonia during the Early Empire] (PDF). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-0293-3.

- Mócsy, András (1974b). Harmatta, János (ed.). Pannónia a késői császárkorban [Pannonia during the Later Empire] (PDF). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-0293-3.

- Benda, Kálmán; Solymosi, László, eds. (1983). Magyarország történeti kronológiája [Historical chronology of Hungary] (PDF). Vol. 1. A kezdetektől 1526-ig. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-3182-8.

- Kovács, Tibor. "őskőkor-vaskor". In Benda & Solymosi (1983).

- Tóth, István. "római kor". In Benda & Solymosi (1983).

- Wilkes, John (1992). The Illyrians (1st ed.). Bodmin: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-14671-7.

- Elekes, Lajos; Lederer, Emma; Székely, György (1961). Magyarország története [History of Hungary] (PDF). Vol. I. Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó.

- Fitz, Jenő (1993–1995). Die Verwaltung Pannoniens in der Römerzeit (four volumes). Budapest: Encyclopedia.

- Petruska, Magdolna (1983). "A Danuvius partján" [On the shore of the Danuvius]. In Gyulás, Istvánné (ed.). Az antik Róma napjai [The days of ancient Rome]. Tankönyvkiadó.

Further reading

[edit]- Parat, Josip. "Izbori i pregledi antičkih literarnih izvora za povijest južne Panonije" [Selections and Surveys of Ancient Literary Sources for the History of Southern Pannonia]. In: Scrinia Slavonica 15, br. 1 (2015): 9-33.

- Fitz, Jenő "RÓMAI MŰVÉSZET PANNONIÁBAN" [Roman art in Pannonia] (2006)

- Fitz, Jenő (1993–1995). Die Verwaltung Pannoniens in der Römerzeit. Four volumes. Budapest: Encyclopedia.

- Kovács, Péter (2014). A history of Pannonia during the Principate. Bonn: Habelt.

- Kovács, Péter (2016). A history of Pannonia in the late Roman period I (284–363 AD). Bonn: Habelt (Review by Eric Fournier in the Journal of Roman Archaeology).

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 680.

- "Pannonia". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). 29 March 2018.

- Pannonia map

- Pannonia map

- Aerial photography: Gorsium - Tác - Hungary

- Aerial photography: Aquincum - Budapest - Hungary

Pannonia

View on GrokipediaGeography and Pre-Roman Context

Physical Features and Boundaries

Pannonia occupied the central portion of the Pannonian Basin, a vast lowland area roughly 600 km east-west and 300 km north-south, formed by tectonic subsidence and filled with Miocene to Quaternary sediments.[4] The basin's flat terrain, dominated by alluvial plains and loess-covered plateaus, facilitated drainage toward the Danube River system but included extensive marshlands along river courses, particularly in the Great Hungarian Plain equivalent.[5] The province's boundaries were defined primarily by natural features: the Danube River served as the northern and eastern frontier, forming a formidable hydrological barrier averaging 300-400 meters wide with variable depths up to 8 meters in channels.[1] To the west, the Eastern Alps' foothills and Noricum's mountainous extensions provided elevation rises to over 1,000 meters, while southward limits abutted the karstic Dinaric Alps and Dalmatia's rugged highlands, exceeding 2,000 meters in peaks.[1] These encircling orographic barriers—the Carpathians northeast, Alps west, and Dinarics south—isolated the basin, creating a discrete physiographic unit conducive to steppe-like vegetation and chernozem soils supporting cereal cultivation.[4][5] Natural resources included fertile alluvial soils yielding grains and pastures, timber from oak and beech forests in the basin's peripheral hills, and mineral deposits such as iron ores in the Alps' approaches and salt in evaporite layers beneath the plains.[5] The continental climate featured hot, dry summers (averaging 20-25°C) and cold winters (down to -5°C), with annual precipitation of 500-700 mm concentrated in spring and autumn, fostering agricultural productivity but complicating overland movement through mud-prone lowlands and flood-prone riparian zones during wet seasons.[5]Indigenous Populations and Cultures

The indigenous populations of pre-Roman Pannonia comprised diverse ethnic groups, primarily Illyrian-speaking Pannonian tribes in the east and south, alongside Celtic settlers in the northwest. The Pannonians formed loose tribal confederations without centralized political structures, exhibiting cultural affinities with neighboring Illyrians through shared onomastics and material practices.[6] Celtic tribes, including the Boii, migrated into the region from the late 4th century BC, establishing dominance in areas like modern western Hungary and eastern Austria by the 3rd century BC.[7] Further Boii influxes occurred around 191 BC following their expulsion from northern Italy, reinforcing their presence along the Danube.[7] Bordering Illyrian groups such as the Dalmatae to the southwest maintained ties through alliances and conflicts, though their core territory lay south of Pannonia proper.[8] Archaeological evidence reveals a material culture blending local traditions with La Tène influences from Celtic arrivals, evident in iron tools, weapons, and distinctive pottery styles from the 4th to 1st centuries BC. Hillforts and proto-urban oppida, such as those in southern Pannonia, served as defensive and communal centers during the Late Iron Age, with settlements featuring sunken buildings and pits indicating semi-sedentary lifestyles.[9] These sites yielded artifacts like fibulae and swords reflecting warrior-oriented societies, while rural dispersions suggest dispersed farmsteads rather than dense urbanization.[9] Societal organization emphasized tribal kinship and warfare, with economies centered on pastoralism—herding cattle, sheep, and horses—supplemented by rudimentary agriculture on alluvial plains and foraging. Inter-tribal raids and confederation-based conflicts over grazing lands and trade routes were common, precluding stable state formation and fostering a martial ethos documented in classical accounts of Pannonian bellicosity.[10] This decentralized structure, reliant on mobility and kinship networks, persisted amid migrations and cultural exchanges until Roman incursions.[10]Roman Conquest and Early Integration

Military Campaigns and Subjugation

The initial Roman efforts to subjugate Pannonia occurred during the campaigns of 12–9 BC, led by Tiberius under Augustus's direction, targeting Pannonian and neighboring tribes to secure the Danube as a frontier. Tiberius advanced from bases like Siscia, employing legionary forces to overcome resistance from groups such as the Scordisci, through a combination of rapid marches, fortified encampments, and punitive raids that disrupted tribal alliances and supply lines. These operations laid preliminary control over the plains between the Drava and Danube rivers, though sporadic unrest persisted.[11] Full pacification was tested by the Pannonian phase of the Great Illyrian Revolt (6–9 AD), sparked when tribes including the Breuci under Bato rebelled amid heavy taxation and legionary withdrawals for Germanic campaigns, mobilizing over 200,000 warriors who besieged Sirmium and raided into Macedonia. Tiberius assumed supreme command in 7 AD, committing approximately 15 legions—about one-third of Rome's total field army—including the XIV Gemina, VIII Augusta, and XV Apollinaris, supported by 20 auxiliary cohorts. His stepsons, Germanicus and Drusus the Younger, directed Pannonian operations, utilizing tactics adapted to the region's swamps and forests: systematic sieges to starve fortified oppida, use of auxiliary cavalry for scouting and flanking guerrilla bands, and massed infantry assaults to shatter rebel concentrations in open terrain.[3] Key engagements included the defense and relief of Siscia, where Roman forces repelled assaults and counterattacked, and pursuits that fragmented the Breuci confederation. By 8–9 AD, coordinated advances under Marcus Caecina Severus and others routed remaining strongholds, with rebel leaders like Bato of the Breuci captured or executed. The suppression incurred severe Roman losses, straining imperial resources and delaying further expansions, but achieved decisive subjugation through relocation of loyal auxiliaries and garrisons to enforce compliance.[3][11]Establishment as a Province

Following the suppression of the Great Illyrian Revolt in AD 9, the Roman Empire formally organized the conquered Pannonian territories as a distinct province under Emperor Tiberius.[1] This step marked the transition from military occupation to structured provincial administration, separating Pannonia from the broader Illyricum governance to address its strategic frontier role along the Danube.[12] Quintus Junius Blaesus served as the initial imperial legate, tasked with stabilizing the region through oversight of legionary forces and local elites.[13] Administrative integration involved conducting a provincial census to evaluate land holdings and population for the imposition of tributum soli and tributum capitis taxes, aligning Pannonia with the fiscal mechanisms of other imperial provinces.[14] This enumeration, typical in newly acquired territories, enabled systematic revenue collection to support military maintenance and infrastructure development, though exact dates for the initial assessment remain undocumented in surviving records.[15] Prior to full separation, Pannonia's administration drew from Illyricum's precedents, incorporating tribal leaders into a hierarchical system under Roman oversight. Infrastructural foundations included demarcating the Danube as the primary limes, with initial fortifications and watchposts to secure the northern boundary against trans-Danubian tribes.[16] Concurrently, road networks were initiated or extended, such as branches connecting to the Via Gemina from Aquileia, enhancing logistics between Italy, Noricum, and Pannonian camps like those at Carnuntum and Aquincum.[17] These efforts prioritized military connectivity over civilian development in the province's formative phase.Administrative and Military Framework

Provincial Divisions and Governance

Pannonia was established as a single imperial province in AD 9 following the suppression of the Great Illyrian Revolt, initially governed by a senatorial legate of praetorian rank appointed by the emperor to oversee both civil and military affairs.[18] This structure emphasized centralized imperial control, with the legate residing at key legionary bases such as Carnuntum to facilitate coordination along the Danube frontier.[19] Under Emperor Trajan, between AD 102 and 107, the province was divided into Pannonia Superior and Pannonia Inferior to enhance administrative efficiency amid expanding Roman commitments in Dacia.[1] Pannonia Superior comprised the western territories, considered more Romanized due to proximity to Italy and Noricum, with its capital at Carnuntum and governed by a senatorial consular legate responsible for higher judicial and fiscal decisions.[19] In contrast, Pannonia Inferior covered the eastern regions, administered by an equestrian prefect of praetorian rank, a post-Domitianic innovation extended post-Flavian era to assign capable but non-senatorial officials to less urbanized areas, thereby reducing senatorial appointments while maintaining oversight.[20] Each division included imperial procurators, equestrian officials who managed finances, tax collection, and imperial estates independently of the governors to prevent corruption and ensure revenue flow to Rome.[21] Taxation in Pannonia followed imperial norms, with the land tax (tributum soli) assessed on agricultural yields and collected via local agents, supplemented by customs duties (portoria) at 2.5 to 5 percent on goods transiting Danube ports, enforced by procuratorial staff to fund provincial infrastructure and legions.[22] Legal administration relied on the governor's edict, aligned with the praetor's edictum perpetuum, applying Roman civil law to citizens while allowing customary practices for provincials under ius gentium, with appeals escalating to the emperor.[21] Municipal self-governance was granted to eligible settlements, such as the colonia of Savaria in Pannonia Superior and municipia like Andautonia in Inferior, where local ordo decurionum councils elected duumviri and aediles annually to handle routine administration, public works, and minor judiciary under charters modeled on Italian municipalities, subject to gubernatorial ratification. This system promoted Romanization by integrating elites into civic roles, though ultimate authority rested with the provincial governor to curb autonomy excesses.[23]Military Presence and Defenses

The Roman military presence in Pannonia was established primarily to defend the Danube frontier against barbarian threats from the north and east, transforming the province into a key bulwark of the empire's Danubian defenses. Following the province's formal organization around 9 CE, it was initially garrisoned with three legions—Legio VIII Augusta, Legio IX Hispana, and Legio XV Apollinaris—to maintain control and deter incursions.[24] By the Flavian period, Legio XIV Gemina Martia Victrix was permanently stationed at the legionary fortress of Carnuntum (near modern Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria), where it remained into the Severan era, housing approximately 5,000-6,000 soldiers in a fortified castra covering about 23 hectares.[3][25] Other major legionary bases included Brigetio (Legio I Adiutrix) and Aquincum (initially auxiliary, later Legio II Adiutrix from 106 CE), forming a chain of heavy infantry strongholds spaced roughly 100-150 km apart along the river.[3][26] Complementing the legions were extensive auxiliary forces, comprising infantry cohorts (cohortes) and cavalry alae totaling tens of thousands of troops recruited from provincial subjects and peripherals. These were quartered in smaller forts (castella) at intervals of 10-30 km along the Danube, such as the Albertfalva auxiliary fort near Aquincum, which accommodated a 500-man cavalry unit protected by palisades, towers, and double ditches for rapid scouting and response to river crossings.[27][28] The network extended to sites like Gerulata and Gorsium, integrating local recruits who provided specialized skills, including archery and horsemanship, essential for patrolling the marshy and forested terrain.[29] The Pannonian Limes, formalized under emperors like Trajan and Hadrian, linked these installations with watchtowers (burgi), signal systems, and earthworks, creating a segmented barrier rather than a continuous wall, optimized for the Danube's dendritic flow and flood-prone banks.[16] This system emphasized mobility, with auxiliary cavalry enabling quick reinforcements to legionary bases during threats, while the overall garrison—estimated at 40,000-50,000 troops across legions and auxiliaries—doubled as a recruitment pool, drawing heavily from Pannonian natives to sustain Danube legions amid high attrition from campaigns and disease.[3][30]Chronological Historical Phases

Julio-Claudian Period

Following the suppression of the Great Illyrian Revolt in 9 AD, led by Tiberius after its outbreak in 6 AD amid a Roman census, Pannonia was formally separated from Illyricum and established as an independent imperial province alongside Dalmatia to facilitate administration and security.[31][32] The revolt's harsh quelling involved decimation of rebellious tribes, relocation of populations, and enslavement of young men from groups like the Breuci and Amantini, measures that ensured short-term pacification but imposed heavy demographic costs.[29] Tiberius maintained a substantial military presence, stationing multiple legions—including the Legio VIII Augusta at Poetovio and Legio XV Apollinaris at Carnuntum—along the Danube frontier to deter further unrest and secure communications.[3] Stabilization efforts under Tiberius and his successors emphasized infrastructure development, with legionary fortresses and early road networks constructed to integrate the province economically and logistically into the empire. These included fortified camps that formed the basis of the Danubian limes, enabling efficient troop movements and resource extraction such as iron and grain from the Pannonian plains.[33] Local recruitment into auxiliary units began during this era, drawing Pannonian tribesmen into Roman service and fostering gradual Romanization, though the core legions remained predominantly Italian or eastern recruits initially.[3] Under Claudius (41–54 AD), administrative refinements included enhanced oversight of provincial finances and military deployments, with Pannonian legions redeployed for the invasion of Britain in 43 AD, demonstrating the province's strategic depth.[34] Nero's reign (54–68 AD) saw intensified fiscal demands across the empire, including heavier taxation on provinces like Pannonia to fund extravagances and eastern campaigns, which strained local economies and sowed seeds of discontent amid reports of administrative corruption.[35] This period marked Pannonia's transition from frontier battleground to a vital supplier of manpower and resources, with emerging provincial loyalty to Rome foreshadowing greater Illyro-Pannonian influence in imperial military structures.[3]Flavian and Adoptive Emperor Eras

Following the instability of the Year of the Four Emperors, Emperor Vespasian (r. 69–79 AD) prioritized frontier stabilization in Pannonia by establishing veteran colonies, including Sirmium and Siscia along the Sava River, to secure loyalty and promote civilian settlement amid ongoing military pressures.[36] [37] These foundations integrated discharged legionaries into the provincial fabric, fostering agricultural development and local governance structures while countering residual unrest from earlier conquests. Domitian (r. 81–96 AD) further reinforced military dispositions against Dacian threats, enhancing legionary camps along the Danube to maintain defensive readiness.[29] Under Trajan (r. 98–117 AD), administrative efficiency prompted the division of Pannonia into Pannonia Superior (western, upstream districts) and Pannonia Inferior (eastern) around 106 AD, facilitating targeted governance and legionary deployments post-Dacian Wars.[29] [1] Hadrian (r. 117–138 AD) emphasized consolidation over expansion, personally inspecting Danube limes fortifications in 118 AD and ordering reinforcements to auxiliary forts and watchtowers, thereby solidifying the frontier against barbarian incursions.[38] [39] The Antonine era under Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161 AD) witnessed relative peace, enabling urban expansion in centers like Aquincum and economic growth through intensified grain production and riverine trade. Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 AD) faced severe tests during the Marcomannic Wars (166–180 AD), as Marcomanni, Quadi, and Sarmatian forces breached Danube defenses, ravaging Pannonian territories and threatening Italy itself, yet Roman legions under his command repelled invasions from bases in Pannonia Superior, achieving decisive victories despite heavy losses.[40] [41] This period marked a peak in Romanization, with widespread adoption of Latin epigraphy, villa estates, and artisanal crafts reflecting deepened cultural integration, underpinned by booming trade networks along the Amber Road and Danube commerce in foodstuffs and metals.[42]Severan and Third-Century Crisis

Septimius Severus (r. 193–211 AD) consolidated power by privileging the Danube legions, including those stationed in Pannonia, through pay raises and donatives that exceeded those granted to other frontier troops, fostering their loyalty amid his campaigns against rivals like Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus.[43] This favoritism elevated Pannonian units, such as Legio I Adiutrix at Brigetio and Legio II Adiutrix at Aquincum, which contributed significantly to Severus' victories, including the Parthian War (195–199 AD), where Pannonian recruits bolstered the army's effectiveness.[3] The policy marked a shift toward reliance on provincial soldiery from Illyricum, setting precedents for later "barrack emperors" emerging from similar backgrounds. The Crisis of the Third Century (c. 235–284 AD) exacerbated vulnerabilities in Pannonia through intensified Sarmatian and Gothic raids across the Danube, beginning with Gothic incursions as early as 238 AD and peaking in devastating invasions during 249–251 AD under Emperor Decius, who perished at Abritus while countering them.[44] Sarmatian Iazyges exploited imperial distractions, raiding Pannonia Superior repeatedly in the 250s AD, contributing to economic strain via disrupted agriculture and trade routes.[45] Amid empire-wide hyperinflation—silver denarius debasement reaching over 90% by 268 AD—Pannonian garrisons faced mutinies over eroded purchasing power, fueling local instability without fully severing Roman administrative control.[46] In 260 AD, news of Emperor Valerian's capture by the Sasanians prompted the usurpation of Ingenuus, Pannonia's governor, proclaimed emperor by troops at Sirmium after victories over invading Sarmatians and Quadi; Gallienus swiftly defeated him at the Battle of Mursa, though successor Regalianus briefly continued the revolt before his suppression.[47] Claims of Pannonia's total "loss" in 260 AD stem from these events and raids but overstate the collapse, as inscriptions, coin finds, and fort occupations (e.g., at Carnuntum) attest to sustained Roman military presence and tax collection into the 270s AD.[48] Emperor Aurelian (r. 270–275 AD) addressed residual threats through campaigns expelling Sarmatians, Goths, and allied Vandals from Pannonia and adjacent provinces, securing the Danube limes by 271–272 AD via decisive engagements that restored legionary discipline and frontier fortifications without territorial concessions.[46] These reconquests mitigated prior usurpations' fallout, such as at Sirmium, a recurring hotspot, by reallocating loyal Illyrian troops and reinforcing economic recovery through stabilized raiding patterns.[49]Late Roman Tetrarchy and Decline

Under Emperor Diocletian, as part of his administrative reforms to enhance control over the empire's provinces, Pannonia was subdivided around 299–303 CE into four smaller units: Pannonia Prima (northwest, capital Savaria), Pannonia Secunda (central-east, capital Sirmium), Valeria (northeast), and Savia (southwest).[50] These divisions aimed to decentralize governance and improve military responsiveness amid ongoing frontier threats, integrating Pannonia more tightly into the Illyricum diocese.[51] During the Tetrarchy established in 293 CE, Sirmium in Pannonia Secunda served as one of the four imperial capitals, assigned to Caesar Galerius, who resided there periodically and used it as a base for campaigns against Sarmatians and Carpi along the Danube.[52] The city's strategic position facilitated rapid mobilization, with its imperial palace complex expanded to host tetrarchic assemblies and administrative functions, underscoring Pannonia's role in stabilizing the eastern frontiers.[52] In 351 CE, the Battle of Mursa Major, fought on September 28 near Sirmium, marked a significant internal conflict when Emperor Constantius II defeated the usurper Magnentius, resulting in heavy casualties estimated at over 50,000 on both sides and weakening the empire's military capacity.[53] This pyrrhic victory highlighted Pannonia's vulnerability as a theater for civil strife, diverting resources from barbarian defenses and exacerbating recruitment strains from local legions.[53] Emperor Valentinian I, originating from Pannonia, prioritized frontier fortifications there during his reign (364–375 CE), constructing or refurbishing defenses along the Danube, including at Aquincum and Sirmium, in response to incursions by Quadi and Sarmatians.[54] In 375 CE, he personally led campaigns into Pannonia against a Quadi coalition, reinforcing limes structures and resettling defeated groups as foederati to bolster auxiliary forces, though his death by apoplexy amid these efforts left the region exposed to renewed pressures.[54][55] By the late 4th century, escalating barbarian federations, including Goths and Sarmatians, prompted greater reliance on foederati settlements within Pannonia, with Roman authorities ceding administrative control over territories to these allies as a stopgap measure; following Theodosius I's death in 395 CE, such concessions accelerated, preluding the province's effective abandonment by central imperial authority.[54]Settlements and Infrastructure

Urban Centers

Carnuntum, established as a temporary military camp around 6 AD under Emperor Tiberius, evolved into the capital of Pannonia Superior by the 1st century AD, serving as a primary administrative hub and hosting the headquarters of the Pannonian fleet from 50 AD onward.[56] The city expanded to accommodate approximately 50,000 inhabitants between the 1st and 4th centuries, featuring public structures that supported its governance role, including a forum and basilica documented through excavations.[56] Aquincum became the capital of Pannonia Inferior following the provincial division under Emperor Trajan around 106 AD, functioning as a central administrative and civilian settlement with infrastructure such as an amphitheater capable of seating thousands, indicative of its municipal status.[57] Inscriptions and ruins confirm its receipt of municipal privileges, bolstering trade and local governance along the Danube frontier.[58] Siscia developed as a strategic port at the confluence of the Sava and Kupa rivers, emerging as a key urban center in Pannonia with administrative significance, including later roles in provincial subdivisions like Pannonia Savia after 295 AD. Its public buildings, such as baths and a theater, reflect municipal development tied to riverine commerce and oversight.[59] Sirmium, located in the lower reaches of the province, gained prominence as an imperial residence and mint from the 3rd century, later designated capital of Pannonia Secunda and a tetrarchic seat under Diocletian around 293 AD.[60] The city's imperial palace complex and mint operations facilitated coin production and high-level administration, with archaeological remains of forums and basilicas attesting to its chartered status and urban functions.[61] Archaeological strata across these centers reveal signals of urban decline in late antiquity, including reduced building activity, abandonment of peripheral zones, and shrinkage of inhabited areas by the 4th century, as evidenced at Carnuntum where portions of the city fell into disuse amid provincial instability.[62] Similar patterns in Sirmium and Aquincum correlate with invasions and administrative shifts, marking a transition from Roman urban vitality to post-imperial contraction.[63]Military Forts and Frontiers

The Roman frontier in Pannonia, known as the Limes Pannonicus, formed a critical segment of the Danube limes system, stretching from the western borders near Vindobona to the eastern reaches near Singidunum. This defensive network comprised legionary fortresses, auxiliary castra, watchtowers, and fortified bridgeheads designed to secure the empire's northern boundary against barbarian incursions from Germanic and Sarmatian tribes. Established progressively from the Augustan era onward, the system evolved with stone constructions and signaling infrastructure under emperors like Marcus Aurelius, incorporating burgi (watchtowers) for visual communication along the riverine barrier.[64] Legionary fortresses anchored the defense, with Brigetio serving as a prime example in Pannonia Superior; this camp, measuring approximately 540 by 430 meters, initially housed Legio XI Claudia pia fidelis before transitioning to Legio I Adiutrix under Trajan around 105 AD, reflecting the strategic reinforcement of the upper Danube. Similarly, other key bases like Carnuntum stationed Legio XIV Gemina, while in Pannonia Inferior, Aquincum accommodated Legio II Adiutrix, each fortress capable of quartering around 5,000-6,000 troops to project power and deter invasions. Auxiliary castra supplemented these, positioned at intervals along the limes; examples include Campona and Matrica, which housed cohort-sized units for patrol and rapid response duties.[65][66] The Classis Pannonica, the provincial river fleet, enhanced mobility and control over the Danube, operating from bases between Castra Regina and Singidunum to support land forces with transport, reconnaissance, and blockades against fluvial threats. Watchtowers and smaller burgi dotted the landscape, enabling fire-signal relays for early warning, a tactic refined amid Marcomannic Wars pressures. In Pannonia Inferior, adaptations addressed Sarmatian nomadic raids beyond the Danube, with archaeological evidence of reinforced limes segments and inland posts indicating a secondary defensive line against Iazyges incursions, as seen in heightened fortification activity during the Tetrarchy era.Rural Economy and Villas

The rural landscape of Pannonia was structured around pagi, administrative districts encompassing clusters of vici, or villages, which facilitated the organization and taxation of agricultural production and local governance.[36] These units supported the exploitation of fertile plains and river valleys for large-scale farming on villae rusticae, elite estates that dominated the countryside and focused on cash crops like wheat and barley for grain, alongside viticulture where imperial permission allowed vine cultivation from the 1st century AD onward.[67] Cattle rearing also played a key role, with mid-Roman increases in livestock reliance evident from zooarchaeological data, supplying meat, dairy, and draft animals essential for estate operations and military provisioning along the Danube frontier.[68] Elite villas, such as those clustered in the Balaton Upland region, exemplified the prosperity of rural landowners, particularly during the Severan era's economic expansion in the early 3rd century AD, when villa construction surged amid heightened provincial investment.[69] These estates featured sophisticated infrastructure, including stables, warehouses, and sometimes mosaics depicting agricultural motifs or mythological scenes, signaling the wealth derived from surplus production and integration into imperial trade networks.[67] Rural mining activities, especially iron extraction in western border zones adjacent to Noricum and limited gold prospecting near the Dacian frontier, supplemented agricultural income, with operations often tied to villa estates employing local labor for ore processing.[70] The stability of this rural economy faltered amid the 3rd-century crisis, as civil strife, barbarian incursions, and imperial instability disrupted settlement patterns, leading to depopulation in exposed countryside areas and a decline in cattle exploitation by the late Roman period.[71][68] Archaeological surveys indicate abandoned villa sites and reduced rural infrastructure in the Danube provinces by the 4th century, reflecting the causal toll of prolonged warfare on labor availability and agricultural output, though some fortified estates persisted under tetrarchic reforms.[72]Economic Foundations

Resources and Agriculture

Pannonia's economy rested heavily on its agricultural output, leveraging the province's expansive fertile plains and alluvial soils along the Danube River and its tributaries for cereal cultivation. Free-threshing wheat dominated production, supplemented by spelt, emmer, millet, rye, and legumes such as lentils and peas, as evidenced by archaeobotanical remains from sites across southern Pannonia.[73] [67] These crops supported both local consumption and surplus generation, with a significant portion of the population engaged in farming to meet provincial needs.[74] Viticulture emerged as a key sector, particularly from the 1st century AD onward, following imperial authorization to expand vineyards in the province. Wines produced in Pannonia, especially in Transdanubia, rivaled those from Italy in quality, reflecting successful adaptation of Mediterranean techniques to local terroir.[75] [67] Animal husbandry complemented arable farming, with emphasis on livestock rearing; horses bred in the region supplied cavalry units of the Roman legions, capitalizing on the plains' suitability for grazing.[76] Natural resources included salt extraction from marshy areas and limited iron ores, though mining remained secondary to agriculture. The Danube's marshes and riverine environments sustained fisheries, yielding species integral to the provincial diet and evidenced in faunal assemblages from Roman settlements.[67] Overall, these endowments enabled self-sufficiency in staples, with agricultural surpluses provisioning military garrisons and allowing excess production without reliance on external imports for basic needs.[73]Trade, Crafts, and Exploitation

Pannonia's strategic location along the Danube River and proximity to overland routes positioned it as a nexus for regional and long-distance trade. The province facilitated commerce via the Amber Road, a prehistoric and Roman-era route extending from the Adriatic northward along the Danube to the Baltic Sea, primarily for importing amber used in luxury goods and exports of wine, ceramics, and metals southward.[77] [78] The Danube served as a vital artery for riverine trade, linking Pannonia with Dacia to the east, where exchanges involved Pannonian agricultural products and ceramics for Dacian gold, iron, and other metals, evidenced by southern Pannonian artifacts in Transylvanian Dacia.[79] [80] Artisanal production in Pannonia emphasized local workshops producing everyday and specialized goods for military, civilian, and export markets. Dozens of kilns across the province, particularly in modern Hungary, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, and Serbia, manufactured bricks, tiles, and pottery, including distinctive Pannonian grey ware (glanztonware) with its glossy finish derived from local clays and firing techniques.[81] [82] Centers like Mursa produced thin-walled tableware imitating Italian styles, while smaller-scale operations in Late Roman times focused on utilitarian ceramics for regional distribution, supported by evidence of local clay sourcing and waster heaps at sites.[83] [84] These crafts contributed to surplus generation, with grain, wool cloth, and livestock exported to supply Italy and frontier legions, bolstering provincial wealth accumulation.[85] Economic exploitation in Pannonia centered on fiscal mechanisms extracting resources for the imperial treasury, including land taxes and customs duties (vectigalia) levied on Danube commerce, which funneled revenues from trade volumes in metals, amber, and agricultural surpluses.[86] Provincial output, particularly grain for the annona system sustaining Rome and military garrisons, integrated Pannonia into empire-wide logistics, with overland and riverine shipments supporting legions and urban centers beyond local needs.[87] This system, enforced through procuratorial oversight, prioritized revenue generation over local reinvestment, channeling Pannonian productivity—estimated to yield substantial capital from fertile plains—directly into central funds for administration and defense.[85]Role of Slavery

Slaves in Roman Pannonia were predominantly sourced from war captives obtained during the province's conquest and subsequent pacification efforts, including the suppression of the Great Illyrian Revolt (6–9 CE), which yielded thousands of Pannonian and allied tribesmen for enslavement following their defeat by Roman forces under Tiberius.[88] Additional supplies came from broader imperial campaigns, such as Trajan's Dacian Wars (101–106 CE), where an estimated 100,000–500,000 Dacians were captured and distributed as slaves across provinces, including Pannonia, to bolster labor needs.[89] These captives supplemented self-sale, debt bondage, and breeding, though the latter were less emphasized in frontier regions like Pannonia compared to Italy. In economic terms, slaves performed essential but secondary roles compared to free provincial labor, primarily in domestic service for elite households, agricultural cultivation on veteran allotments—where legionary families employed slaves to till granted lands—and workshops producing ceramics and metalwork.[71] Evidence from epigraphy indicates limited use in mining, as Pannonia's gold and iron extraction (e.g., at sites near Savaria) relied more on convict labor and free workers than mass slave gangs, contrasting with earlier provinces like Spain.[90] This structure enhanced efficiency in labor-intensive sectors but was constrained by the province's militarized frontier economy, where free recruits and coloni predominated; scholarly assessments note slavery's marginal overall impact, with household sizes rarely exceeding six slaves.[91] Urban centers like Aquincum hosted gladiatorial activities tied to slavery, with the city's amphitheater (capacity ~10,000–13,000) facilitating games where slave gladiators, often war captives, were trained in associated ludi or barracks, as inferred from paired amphitheater complexes in Pannonia Superior.[92] Manumission occurred at moderate rates via testamentary grants or peculium purchases, producing freedmen who integrated into military communities as auxiliaries or traders, evidenced by inscriptions of ex-slaves like Publicius Aper from Pannonia Superior.[93] [94] While no large-scale slave revolts akin to Spartacus's (73–71 BCE) are recorded in Pannonia, localized unrest echoed servile discontent, as frontier garrisons suppressed potential uprisings among captive laborers during the 14 CE legionary mutinies, highlighting tensions from exploitative conditions.[95] This dynamic underscored slavery's utility for short-term coercion but vulnerability to desertion in a permeable border zone, where escape to barbarian territories was feasible.[96]Society, Culture, and Romanization

Social Structures and Demographics

The indigenous population of Roman Pannonia primarily consisted of Pannonian tribes of Illyrian linguistic and cultural stock, with significant Celtic influences in the western areas due to earlier migrations and settlements around the 4th–3rd centuries BC.[97][98] This native base was augmented by Roman military veterans, administrators, and civilian settlers following the province's conquest in 9 BC, creating a heterogeneous demographic mosaic marked by gradual Romanization among elites.[71] Social stratification reflected broader imperial patterns, with urban centers like Aquincum and Sirmium hosting elites comprising Romanized indigenous landowners, Italian merchants, and equestrian officials who managed municipal councils and estates.[37] In contrast, rural areas were dominated by coloni—freeborn tenant farmers who cultivated large latifundia under lease agreements, their status evolving toward hereditary bondage by the 3rd–4th centuries AD amid economic pressures and imperial edicts like those of Constantine.[99] Veteran colonies, such as those at Savaria (established under the Flavians) and Poetovio, further stratified society by granting retired legionaries citizenship and land allotments, fostering a militarized provincial gentry.[71] Demographic dynamics shifted through sustained immigration tied to legionary deployments—Pannonia hosted up to four legions at peak—and outflows from events like the Antonine Plague (AD 165–180), which decimated military garrisons and civilian populations empire-wide, exacerbating labor shortages in frontier zones.[100] The province's strategic importance elevated provincial-born individuals to imperial roles, with several 3rd-century emperors, including Probus (born c. AD 232 near Sirmium) and Claudius II (born c. AD 214 in Sirmium), emerging from Pannonian military families, underscoring pathways for social ascent via service.[54] Funerary epitaphs and stelae reveal family structures centered on nuclear units, with parents commemorating spouses and children—often in mixed Roman and indigenous attire—highlighting intergenerational continuity and emotional ties despite high infant mortality.[101] Gender roles adhered to patriarchal norms, as women were predominantly depicted and inscribed in domestic or familial capacities, though frontier conditions occasionally allowed greater visibility for elite females in commemorative portraits expressing ethnic identity.[101]Cultural Transformations

The process of Romanization in Pannonia involved the gradual integration of Roman administrative, linguistic, and architectural practices, primarily facilitated by military garrisons, veteran settlements, and urban development following the province's establishment in 9 AD. Latin rapidly became the dominant language for official and public use, as evidenced by over 6,000 surviving stone inscriptions, the majority in Latin without indigenous parallels, reflecting a swift linguistic shift among elites and administrators.[71] Bilingual inscriptions, such as the rare Greek-Latin examples or those incorporating Celtic or Illyrian elements, numbered fewer than a dozen, indicating limited persistence of local tongues in formal contexts and a mechanism of cultural assimilation through epigraphic standardization.[102] Public infrastructure symbolized deeper cultural adoption, with cities featuring Roman-style baths and theaters that promoted communal Roman leisure and social norms. For instance, Aquincum, the capital of Pannonia Inferior, included multiple bath complexes and a theater accommodating around 3,000 spectators, constructed by the 2nd century AD, which encouraged participation in Roman entertainment and hygiene practices among urban dwellers. Syncretic elements emerged in nomenclature and iconography, where indigenous motifs blended with Roman styles in non-religious artifacts, though resistance manifested in the retention of local personal names in rural dedications into the 3rd century.[10] The extent of Romanization varied markedly between urban and rural spheres, with cities like Sirmium and Carnuntum exhibiting thorough transformation through imported Roman urbanism, while countryside villas and villages showed superficial adoption, often limited to economic ties rather than full cultural overhaul. Archaeological surveys reveal denser concentrations of Roman-style structures in urban corridors along roads and the Danube, contrasting with sparser evidence in hinterlands where indigenous settlement patterns endured.[103] Scholars debate the depth of this process, with some arguing native identities persisted among lower classes due to limited mobility and education, as onomastic studies indicate Celtic and Illyrian names comprising up to 40% of rural inscriptions by the mid-2nd century, versus under 20% in urban ones.[10] This urban-rural gradient underscores Romanization as an elite-driven phenomenon, unevenly penetrating agrarian communities reliant on pre-Roman subsistence.[104]Daily Life and Material Culture

The diet in Roman Pannonia centered on locally cultivated cereals, particularly barley and millet, which formed the basis of porridge, bread, and other staples, supplemented by pork from extensive regional husbandry practices that supplied both local consumption and imperial markets.[105] [106] Archaeological evidence from faunal remains at sites like Virovitica indicates pigs comprised a significant portion of animal protein, alongside occasional beef and poultry, while plant residues confirm reliance on grains amid variable agricultural yields influenced by the Danube floodplain soils.[67] Lower strata consumed simpler preparations like stews, with elite diets incorporating imported olives or wine sporadically via trade routes. Housing reflected socioeconomic divides: urban dwellers in provincial centers like Aquincum occupied streifenhaus (strip houses) with tiled roofs and basic masonry from the mid-2nd century CE onward, while rural elites resided in villas featuring hypocaust underfloor heating systems for thermal comfort.[107] Commoners and indigenous groups often lived in timber-framed huts or wattle-and-daub structures adapted from pre-Roman traditions, as evidenced by posthole patterns at rural settlements in northeastern Pannonia, lacking advanced Roman amenities but suited to agrarian lifestyles. [108] Everyday tools encompassed iron implements for farming and crafts, such as sickles and needles, alongside bone and antler products like combs and textile-working pins derived from local workshops.[109] Jewelry, including bronze finger rings and earrings, appeared in grave assemblages, signaling status differences—simpler local designs for peasants versus finer imported pieces for higher classes—while grave goods like pottery vessels and glassware further highlighted gradients in material wealth and access to Mediterranean imports.[110] [63] Skeletal remains from provincial cemeteries exhibit markers of nutritional stress, including enamel hypoplasia and stunted stature among lower-class individuals, indicative of periodic malnutrition tied to harvest failures and labor-intensive subsistence.[111]Religious Landscape

Pre-Roman and Local Beliefs