Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Roseate tern

View on Wikipedia

| Roseate tern | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nominate S. d. dougallii with all-black bill, Northumberland, UK | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Sterna |

| Species: | S. dougallii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sterna dougallii Montagu, 1813

| |

| |

The roseate tern (Sterna dougallii) is a species of tern in the family Laridae. The genus name Sterna is derived from Old English "stearn", "tern",[2] and the specific dougallii refers to Scottish physician and collector Dr Peter McDougall (1777–1814).[3] "Roseate" refers to the bird's pink breast in breeding plumage.[4]

Taxonomy

[edit]English naturalist George Montagu described the roseate tern in 1813.[5] Genetically, it is most closely related to the white-fronted tern (S. striata), with their common ancestor a sister lineage to the black-naped tern (S. sumatrana).[6]

This species has a number of geographical subspecies, differing mainly in bill colour and minor plumage details.

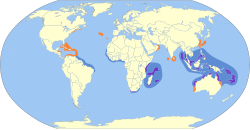

S. d. dougallii breeds on the Atlantic coasts of Europe and North America, and winters south to the Caribbean and west Africa. Both the European and North American populations have been in long-term decline, though active conservation measures have reversed the decline in the last few years at some colonies, most notably at Rockabill Island off the coast of Dublin, Ireland, which now holds most of the European population (about 1200 pairs). The tropical forms S. d. korustes and S. d. bangsi are resident breeders from east Africa across the Indian Ocean to Japan. They have more red on the bill. The long-billed and short-winged S. d. gracilis breeds in Australia and New Caledonia. The north-western Indian Ocean holds populations of S. d. arideensis. Some authors suggest that only three subspecies, nominate S. d. dougallii, S. d. arideensis, and S. d. gracilis, should be retained.[7][8]

Description

[edit]

This is a small-medium tern, 33–36 cm (13–14 in) long with a 67–76 cm (26–30 in) wingspan, which can be confused with the common tern, Arctic tern, and the larger, but similarly plumaged, Sandwich tern. The thin sharp bill is black, with a red base which develops through the breeding season, and is more extensive (to fully red) in the tropical and southern hemisphere subspecies. It is shorter-winged and has faster wing beats than common or Arctic tern. The upper wings are pale grey and its under parts white, and this tern looks very pale in flight, like a small Sandwich tern, although the outermost primary flight feathers darken during the summer. The adults have very long, flexible tail streamers and orange-red legs. In summer, the underparts of adults take on the pinkish tinge which gives this bird its name.

In winter, the forehead becomes white and the bill black. Juvenile roseate terns have a scaly appearance like juvenile Sandwich Terns, but a fuller black cap than that species.

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]Food and feeding

[edit]As with other Sterna terns, roseate tern feeds by plunge-diving for fish, almost invariably from the sea; it is much more marine than allied terns, only rarely visiting freshwater lagoons on the coast to bathe and not fishing in fresh water. It usually dives directly, and not from the "stepped-hover" favoured by Arctic tern. The offering of fish by the male to the female is part of the courtship display.

Unusual for a tern, the roseate tern shows some kleptoparasitic behaviour, stealing fish from other seabirds, at British colonies most often from puffins. This habit greatly increases their food-collecting ability during bad weather when fish swim deeper, out of reach of plunge-diving terns, but still within reach of the deeper-diving Puffins.

Breeding

[edit]This species breeds in colonies on coasts and islands, at times with other seabirds. In Australian colonies, it has been recorded nesting alongside the black-naped tern (S. sumatrana), lesser crested tern (Thalasseus bengalensis), greater crested tern (T. bergii), fairy tern (Sternula nereis), bridled tern (Onychoprion anaethetus) and silver gull (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae).[9] It nests in a ground scrape, often in a hollow or under dense vegetation, and lays one or two (rarely three) eggs. It is less defensive of its nest and young than other white terns, often relying on Arctic and common terns in the surrounding colony to defend them. In smaller colonies, they may rarely mate with these other tern species.

The white-bellied sea-eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) and silver gull are known to prey on eggs and chicks, while the turnstone (Arenaria interpres), black rat (Rattus rattus) and King's skink (Egernia kingii) are suspected predators.[9]

Vocalisations

[edit]The call of the roseate tern is a very characteristic chuwit, similar to that of the spotted redshank, quite distinct from other terns.

Conservation status

[edit]

In the late 19th century, these birds were hunted for their plumes which were used to decorate hats. More recently, their numbers have decreased in some regions due to increased competition and predation by large gulls, whose numbers have increased in recent times. This species, as of 2019, is one of the UK's rarest breeding seabird.[10]

The largest European colony, accounting for more than 75% of the European population, is in Ireland, at Rockabill Island, County Dublin. In 2013, 1213 pairs nested at Rockabill. The colony at Lady's Island Lake, County Wexford, is also of crucial importance, with 155 pairs nesting there in 2013.[11]

With their favouring partly hidden nest sites, the provision of nestboxes has proven a dramatic conservation success, with the birds taking to them very readily. This results in greatly increased breeding productivity with the protection given to the young from predatory birds like herring gulls. At the UK's most important colony, on Coquet Island, Northumberland, the population rose from 25 pairs 1997 to 154 pairs in 2022 after nestboxes were provided. Similar measures have been undertaken at the Anglesey tern colonies along with clearance of vegetation, in particular Tree Mallow. In 2018, for the first time in more than a decade, a pair fledged two chicks on the Skerries, off Anglesey after a RSPB project over previous years involving wardening, newly designed nest boxes being placed strategically around the islands along with lures playing roseate tern calls and hand-made decoys.[10]

In the UK the roseate tern has been designated for protection under the official government's national Biodiversity Action Plan. One of the main reasons given in the UK plan for threat to the species is global warming, creating an alteration of vertical profile distribution for its food source fishes. The roseate tern is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.

The Canadian Wildlife Service lists the roseate tern as Threatened. The U.S. Department of Interior lists the northeastern population as Endangered and the Caribbean population as Threatened.[12]

-

Late in the breeding season, the bill base on S. d. dougallii turns red. Puerto Rico.

-

Egg of Sterna dougallii dougallii - Muséum de Toulouse

-

Egg of Sterna dougallii bangsi - Muséum de Toulouse

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Sterna dougallii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T22694601A132260491. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22694601A132260491.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "Sterna". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Roseate". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Montagu, George (1813). "Tern-Roseate Sterna dougallii". Supplement to the Ornithological Dictionary, or Synopsis of British Birds. Exeter, England: Printed by S. Woolmer. The pages are not numbered.

- ^ Bridge, Eli S; Jones, Andrew W; Baker, Allan J (2005). "A phylogenetic framework for the terns (Sternini) inferred from mtDNA sequences: implications for taxonomy and plumage evolution" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 35 (2): 459–469. Bibcode:2005MolPE..35..459B. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.12.010. PMID 15804415. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-19.

- ^ Gochfeld, M. & Burger, J. 1996. Family Sternidae (terns). In: Del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A A. & Sargatal, J. (Eds). Handbook of birds of the world, Vol. 3. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. pp. 624–667.

- ^ Tree, AJ (2005) The known history and movements of the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in South Africa and the western Indian Ocean. Marine Ornithology 33:41-47 PDF

- ^ a b Department of the Environment (2015). "Sterna dougallii — Roseate Tern". Species Profile and Threats Database. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Government. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Celebrating recent successes around Wales - RSPB Cymru Blog - We love Wales! - the RSPB Community". 19 June 2019.

- ^ Annual Report of the Irish Rare Birds Breeding Panel 2013

- ^ Nisbet, Ian C.; Gochfeld, Michael; Burger, Joanna (2014). "Roseate Tern". Birds of North America Online. Ithaca, New York: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

External links

[edit]Roseate tern

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy

Classification and Subspecies

The roseate tern (Sterna dougallii) is classified in the family Laridae, order Charadriiformes, encompassing seabirds such as gulls, terns, and skimmers. Within the genus Sterna, which derives from the Old English term "stearn" for tern, the species was formally described by George Montagu in 1813 based on a specimen from Barbados provided by Scottish physician and naturalist James Douglas (1675–1778), hence the specific epithet dougallii.[9][1] The species comprises multiple subspecies, differentiated primarily by subtle morphological traits including body size, bill proportions, and plumage nuances, with genetic evidence from mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite analyses supporting historical divergence times on the order of 3.9% sequence divergence between major lineages.[10][11] The nominate subspecies S. d. dougallii predominates in the North Atlantic, characterized by relatively larger size and distinct bill coloration compared to tropical counterparts.[2] In the Indo-Pacific, S. d. bangsi represents a distinct form with adaptations reflected in size and genetic structuring, while molecular studies reveal persistent differentiation between northwestern Atlantic and Caribbean populations, though formal subspecies designation for the latter remains under evaluation based on ongoing genomic data.[12][13] These divisions underscore allopatric evolutionary processes without evidence of widespread gene flow sufficient to homogenize populations.[11]Physical Description

Morphology and Plumage Variations

The roseate tern (Sterna dougallii) possesses a slender, graceful morphology adapted for agile aerial pursuits, featuring a deeply forked tail that forms prominent streamers in flight. Adults typically measure 33–41 cm in total length, inclusive of 13–22 cm tail streamers, with a wingspan of 72–80 cm and body mass ranging from 95–130 g (mean approximately 110 g in northeastern populations).[14][15][4] Breeding adults exhibit pale gray upperparts, white underparts often tinged with a subtle roseate flush on the breast and belly, a glossy black cap covering the crown and nape, and a black bill with a variable red-orange base that intensifies later in the season. The primaries include dark outer feathers, and the legs and feet are red. In non-breeding plumage, the forehead becomes whiter, the rosy tones fade, and the bill shortens and appears entirely black.[16][17][18] Sexual dimorphism is minimal, with no plumage distinctions between sexes; males average slightly larger in linear measurements such as wing length (21.2–24.2 cm) and tail streamer length. Juveniles differ markedly with brownish-gray upperparts featuring a scaly appearance from broad dark feather tips, transitioning through pre-basic molts to adult-like plumage within the first year, as documented in banding recoveries.[19][20][17][18]