Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chlorophyta

View on Wikipedia

| Chlorophyta Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

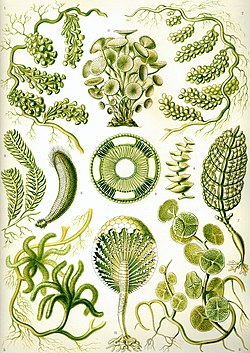

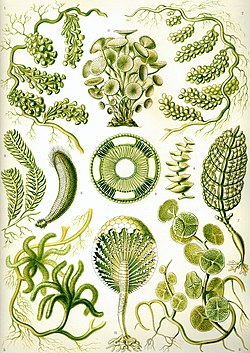

| "Siphoneae" from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Chlorophyta Reichenbach, 1828, emend. Pascher, 1914, emend. Lewis & McCourt, 2004[2][3][4] |

| Classes[5] | |

| Diversity | |

| 7,934 species (6,851 living, 1,083 fossil)[6] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Chlorophyta[a] is a division of green algae informally called chlorophytes.[9]

Description

[edit]Chlorophytes are eukaryotic organisms composed of cells with a variety of coverings or walls, and usually a single green chloroplast in each cell.[4] They are structurally diverse: most groups of chlorophytes are unicellular, such as the earliest-diverging prasinophytes, but in two major classes (Chlorophyceae and Ulvophyceae) there is an evolutionary trend toward various types of complex colonies and even multicellularity.[8]

Chloroplasts

[edit]Chlorophyte cells contain green chloroplasts surrounded by a double-membrane envelope. These contain chlorophylls a and b, and the carotenoids carotin, lutein, zeaxanthin, antheraxanthin, violaxanthin, and neoxanthin, which are also present in the leaves of land plants. Some special carotenoids are present in certain groups, or are synthesized under specific environmental factors, such as siphonaxanthin, prasinoxanthin, echinenone, canthaxanthin, loroxanthin, and astaxanthin. They accumulate carotenoids under nitrogen deficiency, high irradiance of sunlight, or high salinity.[10][11] In addition, they store starch inside the chloroplast as carbohydrate reserves.[8] The thylakoids can appear single or in stacks.[4] In contrast to other divisions of algae such as Ochrophyta, chlorophytes lack a chloroplast endoplasmic reticulum.[12]

Flagellar apparatus

[edit]Chlorophytes often form flagellate cells that generally have two or four flagella of equal length, although in prasinophytes heteromorphic (i.e. differently shaped) flagella are common because different stages of flagellar maturation are displayed in the same cell.[13] Flagella have been independently lost in some groups, such as the Chlorococcales.[8] Flagellate chlorophyte cells have symmetrical cross-shaped ('cruciate') root systems, in which ciliary rootlets with a variable high number of microtubules alternate with rootlets composed of just two microtubules; this forms an arrangement known as the "X-2-X-2" arrangement, unique to chlorophytes.[14] They are also distinguished from streptophytes by the place where their flagella are inserted: directly at the cell apex, whereas streptophyte flagella are inserted at the sides of the cell apex (sub-apically).[15]

Below the flagellar apparatus of prasinophytes are rhizoplasts, contractile muscle-like structures that sometimes connect with the chloroplast or the cell membrane.[13] In core chlorophytes, this structure connects directly with the surface of the nucleus.[16]

The surface of flagella lacks microtubular hairs, but some genera present scales or fibrillar hairs.[11] The earliest-branching groups have flagella often covered in at least one layer of scales, if not naked.[13]

Metabolism

[edit]Chlorophytes and streptophytes differ in the enzymes and organelles involved in photorespiration. Chlorophyte algae use a dehydrogenase inside the mitochondria to process glycolate during photorespiration. In contrast, streptophytes (including land plants) use peroxisomes that contain glycolate oxidase, which converts glycolate to glycoxylate, and the hydrogen peroxide created as a subproduct is reduced by catalases located in the same organelles.[17]

Reproduction and life cycle

[edit]Asexual reproduction is widely observed in chlorophytes. Among core chlorophytes, both unicellular groups can reproduce asexually through autospores,[18] wall-less zoospores,[19] fragmentation, plain cell division, and exceptionally budding.[20] Multicellular thalli can reproduce asexually through motile zoospores,[21] non-motile aplanospores, autospores, filament fragmentation,[22] differentiated resting cells,[23] and even unmated gametes.[24] Colonial groups can reproduce asexually through the formation of autocolonies, where each cell divides to form a colony with the same number and arrangement of cells as the parent colony.[25]

Many chlorophytes exclusively conduct asexual reproduction, but some display sexual reproduction, which may be isogamous (i.e., gametes of both sexes are identical), anisogamous (gametes are different) or oogamous (gametes are sperm and egg cells), with an evolutionary tendency towards oogamy. Their gametes are usually specialized cells differentiated from vegetative cells, although in unicellular Volvocales the vegetative cells can function simultaneously as gametes. Most chlorophytes have a diplontic life cycle (also known as zygotic), where the gametes fuse into a zygote which germinates, grows and eventually undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores (gametes), similarly to ochrophytes and animals. Some exceptions display a haplodiplontic life cycle, where there is an alternation of generations, similarly to land plants.[26] These generations can be isomorphic (i.e., of similar shape and size) or heteromorphic.[27] The formation of reproductive cells usually does not occur in specialized cells,[28] but some Ulvophyceae have specialized reproductive structures: gametangia, to produce gametes, and sporangia, to produce spores.[27]

The earliest-diverging unicellular chlorophytes (prasinophytes) produce walled resistant stages called cysts or 'phycoma' stages before reproduction; in some groups the cysts are as large as 230 μm in diameter. To develop them, the flagellate cells form an inner wall by discharging mucilage vesicles to the outside, increase the level of lipids in the cytoplasm to enhance buoyancy, and finally develop an outer wall. Inside the cysts, the nucleus and cytoplasm undergo division into numerous flagellate cells that are released by rupturing the wall. In some species these daughter cells have been confirmed to be gametes; otherwise, sexual reproduction is unknown in prasinophytes.[29]

Ecology

[edit]Free-living

[edit]

Chlorophytes are an important portion of the phytoplankton in both freshwater and marine habitats, fixating more than a billion tons of carbon every year. They also live as multicellular macroalgae, or seaweeds, settled along rocky ocean shores.[8] Most species of Chlorophyta are aquatic, prevalent in both marine and freshwater environments. About 90% of all known species live in freshwater.[30] Some species have adapted to a wide range of terrestrial environments. For example, Chlamydomonas nivalis lives on summer alpine snowfields, and Trentepohlia species, live attached to rocks or woody parts of trees.[31][32] Several species have adapted to specialised and extreme environments, such as deserts, arctic environments, hypersaline habitats, marine deep waters, deep-sea hydrothermal vents and habitats that experience extreme changes in temperature, light and salinity.[33][34][35] Some groups, such as the Trentepohliales, are exclusively found on land.[36][37]

Symbionts

[edit]Several species of Chlorophyta live in symbiosis with a diverse range of eukaryotes, including fungi (to form lichens), ciliates, forams, cnidarians and molluscs.[32] Some species of Chlorophyta are heterotrophic, either free-living or parasitic.[38][39] Others are mixotrophic bacterivores through phagocytosis.[40] Two common species of the heterotrophic green alga Prototheca are pathogenic and can cause the disease protothecosis in humans and animals.[41]

With the exception of the three classes Ulvophyceae, Trebouxiophyceae and Chlorophyceae in the UTC clade, which show various degrees of multicellularity, all the Chlorophyta lineages are unicellular.[42] Some members of the group form symbiotic relationships with protozoa, sponges, and cnidarians. Others form symbiotic relationships with fungi to form lichens, but the majority of species are free-living. All members of the clade have motile flagellated swimming cells.[43] Monostroma kuroshiense, an edible green alga cultivated worldwide and most expensive among green algae, belongs to this group.

Systematics

[edit]Taxonomic history

[edit]The first mention of Chlorophyta belongs to German botanist Heinrich Gottlieb Ludwig Reichenbach in his 1828 work Conspectus regni vegetabilis. Under this name, he grouped all algae, mosses ('musci') and ferns ('filices'), as well as some seed plants (Zamia and Cycas).[44] This usage did not gain popularity. In 1914, Bohemian botanist Adolf Pascher modified the name to encompass exclusively green algae, that is, algae which contain chlorophylls a and b and store starch in their chloroplasts.[45] Pascher established a scheme where Chlorophyta was composed of two groups: Chlorophyceae, which included algae now known as Chlorophyta, and Conjugatae, which are now known as Zygnematales and belong to the Streptophyta clade from which land plants evolved.[3][46]

During the 20th century, many different classification schemes for the Chlorophyta arose. The Smith system, published in 1938 by American botanist Gilbert Morgan Smith, distinguished two classes: Chlorophyceae, which contained all green algae (unicellular and multicellular) that did not grow through an apical cell; and Charophyceae, which contained only multicellular green algae that grew via an apical cell and had special sterile envelopes to protect the sex organs.[47]

With the advent of electron microscopy studies, botanists published various classification proposals based on finer cellular structures and phenomena, such as mitosis, cytokinesis, cytoskeleton, flagella and cell wall polysaccharides.[48][49] British botanist Frank Eric Round proposed in 1971 a scheme which distinguishes Chlorophyta from other green algal divisions Charophyta, Prasinophyta and Euglenophyta. He included four classes of chlorophytes: Zygnemaphyceae, Oedogoniophyceae, Chlorophyceae and Bryopsidophyceae.[50] Other proposals retained the Chlorophyta as containing all green algae, and varied from one another in the number of classes. For example, the 1984 proposal by Mattox & Stewart included five classes,[48] while the 1985 proposal by Bold & Wynne included only two,[51] and the 1995 proposal by Christiaan van den Hoek and coauthors included up to eleven classes.[45]

The modern usage of the name 'Chlorophyta' was established in 2004, when phycologists Lewis & McCourt firmly separated the chlorophytes from the streptophytes on the basis of molecular phylogenetics. All green algae that were more closely related to land plants than to chlorophytes were grouped as a paraphyletic division Charophyta.[46]

Within the green algae, the earliest-branching lineages were grouped under the informal name of "prasinophytes", and they were all believed to belong to the Chlorophyta clade.[46] However, in 2020 a study recovered a new clade and division known as Prasinodermophyta, which contains two prasinophyte lineages previously considered chlorophytes.[52] Below is a cladogram representing the current state of green algal classification:[53][52][54][55]

| Viridiplantae |

|

|||||||||||||

Classification

[edit](Ulvophyceae)

Currently eleven chlorophyte classes are accepted, here presented in alphabetical order with some of their characteristics and biodiversity:

- Chlorodendrophyceae (60 species, 15 extinct):[6] unicellular flagellates (monadoids) surrounded by an outer cell covering or theca of organic extracellular scales composed of proteins and ketosugars. Some of these scales make up hair-like structures. Capable of asexual reproduction through cell division inside the theca. No sexual reproduction has been described. Each cell contains a single chloroplast and exhibits two flagella. Present in marine and freshwater habitats.[56][57][58]

- Chlorophyceae (3,974 species):[6] either unicellular monadoids (flagellated) or coccoids (without flagella) living solitary or in varied colonial forms (including coenobial), or multicellular filamentous (branch-like) thalli that may be ramified, or foliose (leaf-like) thalli. Cells are surrounded by a crystalline covering composed of glycoproteins abundant in glycine and hydroxyproline, as well as pectins, arabinogalactan proteins, and extensin. They exhibit a haplontic life cycle with isogamy, anisogamy or oogamy. They are capable of asexual reproduction through flagellated zoospores, aplanospores, or autospores. Each cell contains a single chloroplast, a variable number of pyrenoids (including lack thereof), and from one to hundreds of flagella without mastigonemes. Present in marine, freshwater and terrestrial habitats.[59][32][60][61]

- Chloropicophyceae (8 species):[6] unicellular solitary coccoids. Cells are surrounded by a multi-layered cell wall. No sexual or asexual reproduction has been described. Each cell contains a single chloroplast with astaxanthin and loroxanthin, and lacks pyrenoids or flagella. They are exclusively marine.[53]

- Chuariophyceae (3 extinct species): exclusively fossil group containing carbonaceous megafossils found in Ediacaran rocks, such as Tawuia.[6][62]

- Mamiellophyceae (25 species):[6] unicellular solitary monadoids. Cells are naked or covered by one or two layers of flat scales, mainly with spiderweb-like or reticulate ornamentation. Each cell contains one or rarely two chloroplasts, almost always with prasinoxanthin; two equal or unequal flagella, or just one flagellum, or lacking any flagella. If flagella are present, they can be either smooth or covered in scales in the same manner as the cells. Present in marine and freshwater habitats.[63][57]

- Nephroselmidophyceae (29 species):[6] unicellular monadoids. Cells are covered by scales. They are capable of sexual reproduction through hologamy (fusion of entire cells), and of asexual reproduction through binary fission. Each cell contains a single chloroplast, a pyrenoid, and two flagella covered by scales. Present in marine and freshwater habitats.[64][65][57]

- Pedinophyceae (24 species):[6] unicellular asymmetrical monadoids that undergo a coccoid palmelloid phase covered by mucilage. Cells lack extracellular scales, but in rare cases are covered on the posterior side by a theca. Each cell contains a single chloroplast, a pyrenoid, and a single flagellum usually covered in mastigonemes. Present in marine, freshwater and terrestrial habitats.[66][57][67]

- Picocystophyceae (1 species):[6] unicellular coccoids, ovoid and trilobed in shape. Cells are surrounded by a multi-layered cell wall of poly-arabinose, mannose, galactose and glucose. No sexual reproduction has been described. They are capable of asexual reproduction through autosporulation, resulting in two or rarely four daughter cells. Each cell contains a single bilobed chloroplast with diatoxanthin and monadoxanthin, without any pyrenoid or flagella. Present in saline lakes.[68][53][57]

- Pyramimonadophyceae (166 species, 59 extinct):[6] unicellular monadoids or coccoids. Cells are covered by two or more layers of organic scales. No sexual reproduction has been described, but some cells with only one flagellum have been interpreted as potential gametes. Asexual reproduction has only been observed in the coccoid forms, via zoospores. Each cell contains a single chloroplast, a pyrenoid, and between 4 and 16 flagella. The flagella are covered in at least two layers of organic scales: a bottom layer of pentagonal scales organized in 24 rows, and a top layer of limuloid scales distributed in 11 rows. They are exclusively marine.[57][69]

- Trebouxiophyceae (926 species, 1 extinct):[6] unicellular monadoids occasionally without flagella, or colonial, or ramified filamentous thalli, or living as the photobionts of lichen. Cells are covered by a cell wall of cellulose, algaenans, and β-galactofuranane. No sexual reproduction has been described with the exception of some observations of gamete fusion and presence of meiotic genes. They are capable of asexual reproduction through autospores or zoospores. Each cell contains a single chloroplast, a pyrenoid, and one or two pairs of smooth flagella. They are present in marine, freshwater and terrestrial habitats.[59][70][4][71]

- Ulvophyceae (2,695 species, 990 extinct):[6] macroscopic thalli, either filamentous (which may be ramified) or foliose (composed of monostromatic or distromatic layers) or even compact tubular forms, generally multinucleate. Cells surrounded by a cell wall that may be calcified, composed of cellulose, β-manane, β-xilane, sulphated or piruvilated polysaccharides or sulphated ramnogalacturonanes, arabinogalactan proteins, and extensin. They exhibit a haplodiplontic life cycle where the alternating generations can be isomorphic or heteromorphic. They reproduce asexually via zoospores that may be covered in scales. Each cell contains a single chloroplast, and one or two pairs of flagella without mastigonemes but covered in scales. They are present in marine, freshwater and terrestrial habitats.[59][4][72]

Evolution

[edit]In February 2020, the fossilized remains of a green alga, named Proterocladus antiquus were discovered in the northern province of Liaoning, China. At around a billion years old, it is believed to be one of the oldest examples of a multicellular chlorophyte. It is currently classified as a member of order Siphonocladales, class Ulvophyceae.[1] In 2023, a study calculated the molecular age of green algae as calibrated by this fossil. The study estimated the origin of Chlorophyta within the Mesoproterozoic era, at around 2.04–1.23 billion years ago.[55]

Usage

[edit]Model organisms

[edit]Among chlorophytes, a small group known as the volvocine green algae is being researched to understand the origins of cell differentiation and multicellularity. In particular, the unicellular flagellate Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and the colonial organism Volvox carteri are object of interest due to sharing homologous genes that in Volvox are directly involved in the development of two different cell types with full division of labor between swimming and reproduction, whereas in Chlamydomonas only one cell type exists that can function as a gamete. Other volvocine species, with intermediate characters between these two, are studied to further understand the transition towards the cellular division of labor, namely Gonium pectorale, Pandorina morum, Eudorina elegans and Pleodorina starrii.[73]

Industrial uses

[edit]Chlorophyte microalgae are a valuable source of biofuel and various chemicals and products in industrial amounts, such as carotenoids, vitamins and unsaturated fatty acids. The genus Botryococcus is an efficient producer of hydrocarbons, which are converted into biodiesel. Various genera (Chlorella, Scenedesmus, Haematococcus, Dunaliella and Tetraselmis) are used as cellular factories of biomass, lipids and different vitamins for either human or animal consumption, and even for usage as pharmaceuticals. Some of their pigments are employed for cosmetics.[74]

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Tang et al. 2020.

- ^ Reichenbach 1828, p. 23.

- ^ a b Pascher 1914.

- ^ a b c d e Adl et al. 2019, p. 36.

- ^ Guiry 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Guiry 2024, p. 5.

- ^ Papenfuss 1955.

- ^ a b c d e Margulis & Chapman 2009, p. 200.

- ^ Rockwell et al. 2017.

- ^ Solovchenko et al. 2010.

- ^ a b Lee 2018, p. 309.

- ^ Lee 2018, p. 310.

- ^ a b c Graham et al. 2022, pp. 16–15.

- ^ Lewis & McCourt 2004, p. 1537.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, pp. 16–10.

- ^ Yamashita & Baluška 2023, p. 2.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 16-11.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 17-8.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 17-11.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 17-9.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 18-8.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 19-3.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 18-19.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 18-29.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 19-14.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 16-13.

- ^ a b Graham et al. 2022, p. 18-14.

- ^ Lee 2018, p. 318.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 16-17.

- ^ Lee 2018.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022.

- ^ a b c Leliaert et al. 2012.

- ^ Lewis & Lewis 2005.

- ^ De Wever et al. 2009.

- ^ Leliaert, Verbruggen & Zechman 2011.

- ^ López-Bautista, Rindi & Guiry 2006.

- ^ Foflonker et al. 2016.

- ^ Joubert & Rijkenberg 1971.

- ^ Nedelcu 2001.

- ^ Anderson, Charvet & Hansen 2018.

- ^ Tartar et al. 2002.

- ^ Umen 2014.

- ^ Kapraun 2007.

- ^ Reichenbach 1828, p. 23–40.

- ^ a b van den Hoek, Mann & Jahns 1995.

- ^ a b c Lewis & McCourt 2004.

- ^ Smith 1938, p. 12.

- ^ a b Mattox & Stewart 1984.

- ^ Lobban & Wynne 1981, p. 88.

- ^ Round 1971.

- ^ Bold & Wynne 1985.

- ^ a b Li et al. 2020.

- ^ a b c Lopes dos Santos et al. 2017.

- ^ Gulbrandsen et al. 2021.

- ^ a b Yang et al. 2023.

- ^ Hori, Norris & Chihara 1986.

- ^ a b c d e f Adl et al. 2019, p. 37.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 17-2.

- ^ a b c Domozych et al. 2012.

- ^ Adl et al. 2019, p. 36–37.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 19-2–19-5.

- ^ Srivastava 2002.

- ^ Marin & Melkonian 2010.

- ^ Nakayama et al. 2007.

- ^ Yamaguchi et al. 2010.

- ^ Marin 2012.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 17-3.

- ^ Lewin et al. 2000.

- ^ Daugbjerg, Fassel & Moestrup 2020.

- ^ Fučíková, Pažoutová & Rindi 2015.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 17-4–17-11.

- ^ Graham et al. 2022, p. 18-2–18-24.

- ^ Nishii & Miller 2010.

- ^ Baudelet et al. 2017.

Cited literature

[edit]- Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W.; Burki, Fabien; et al. (2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/JEU.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- Anderson, R.; Charvet, S.; Hansen, P. J. (2018). "Mixotrophy in Chlorophytes and Haptophytes—Effect of Irradiance, Macronutrient, Micronutrient and Vitamin Limitation". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9 1704. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01704. PMC 6080504. PMID 30108563.

- Baudelet, Paul-Hubert; Ricochon, Guillaume; Linder, Michel; Muniglia, Lionel (2017). "A new insight into cell walls of Chlorophyta". Algal Research. 25 (1): 333–371. Bibcode:2017AlgRe..25..333B. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2017.04.008.

- Becker, Burkhard; Marin, Birger (2009). "Streptophyte algae and the origin of embryophytes". Annals of Botany. 103 (7): 999–1004. doi:10.1093/aob/mcp044. PMC 2707909. PMID 19273476.

- Bold, Harold Charles; Wynne, Michael James (1985). Introduction to the algae: structure and reproduction (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-1347-7746-7.

- Daugbjerg, Niels; Fassel, Nicolai M. D.; Moestrup, Øjvind (2020). "Microscopy and phylogeny of Pyramimonas tatianae sp. nov. (Pyramimonadales, Chlorophyta), a scaly quadriflagellate from Golden Horn Bay (eastern Russia) and formal description of Pyramimonadophyceae classis nova". European Journal of Phycology. 55 (1): 49–63. Bibcode:2020EJPhy..55...49D. doi:10.1080/09670262.2019.1638524.

- De Wever, Aaike; Leliaert, Frederik; Verleyen, Elie; Vanormelingen, Pieter; Van der Gucht, Katleen; Hodgson, Dominic A.; Sabbe, Koen; Vyverman, Wim (October 2009). "Hidden levels of phylodiversity in Antarctic green algae: further evidence for the existence of glacial refugia". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1673): 3591–3599. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0994. PMC 2817313. PMID 19625320.

- Domozych, David S.; Ciancia, Marina; Fangel, Jonatan U.; Mikkelsen, Maria Dalgaard; Ulvskov, Peter; Willats, William G. T. (2012). "The Cell Walls of Green Algae: A Journey through Evolution and Diversity". Frontiers in Plant Science. 3: 82. Bibcode:2012FrPS....3...82D. doi:10.3389/fpls.2012.00082. PMC 3355577. PMID 22639667.

- Foflonker, Fatima; Ananyev, Gennady; Qiu, Huan; Morrison, Andrenette; Palenik, Brian; Dismukes, G. Charles; Bhattacharya, Debashish (June 2016). "The unexpected extremophile: Tolerance to fluctuating salinity in the green alga Picochlorum". Algal Research. 16: 465–472. Bibcode:2016AlgRe..16..465F. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2016.04.003. OSTI 1619391.

- Fučíková, Karolina; Pažoutová, Marie; Rindi, Fabio (2015). "Meiotic genes and sexual reproduction in the green algal class Trebouxiophyceae (Chlorophyta)". Journal of Phycology. 51 (3): 419–430. Bibcode:2015JPcgy..51..419F. doi:10.1111/jpy.12293. PMID 26986659.

- Graham, Linda E.; Graham, James M.; Wilcox, Lee W.; Cook, Martha E. (2022). Algae (4th ed.). LJLM Press. ISBN 978-0-9863-9354-9.

- Guiry, Michael D. (2024). "How many species of algae are there? A reprise. Four kingdoms, 14 phyla, 63 classes and still growing". Journal of Phycology. 60 (2): 214–228. Bibcode:2024JPcgy..60..214G. doi:10.1111/jpy.13431. PMID 38245909.

- Gulbrandsen, Øyvind Sætren; Andresen, Ina Jungersen; Krabberød, Anders Kristian; Bråte, Jon; Shalchian-Tabrizi, Kamran (2021). "Phylogenomic analysis restructures the Ulvophyceae". Journal of Phycology. 57 (4): 1223–1233. Bibcode:2021JPcgy..57.1223G. doi:10.1111/jpy.13168. hdl:11250/2778617. PMID 33721355.

- Hori, Terumitsu; Norris, Richard E.; Chihara, Mitsuo (1986). "Studies on the Ultrastructure and Taxonomy of the Genus Tetraselmis (Prasinophyceae) III. Subgenus Parviselmis". Shokubutsugaku Zasshi [The Botanical Magazine, Tokyo]. 99 (1): 123–135. Bibcode:1986JPlR...99..123H. doi:10.1007/BF02488627.

- Joubert, J. J.; Rijkenberg, F. H. (1971). "Parasitic green algae". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 9 (1): 45–64. Bibcode:1971AnRvP...9...45J. doi:10.1146/annurev.py.09.090171.000401.

- Kapraun, Donald F. (April 2007). "Nuclear DNA content estimates in green algal lineages: chlorophyta and streptophyta". Annals of Botany. 99 (4): 677–701. doi:10.1093/aob/mcl294. PMC 2802934. PMID 17272304.

- Lee, Robert Edward (2018). "Chlorophyta". Phycology (5th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–230. doi:10.1017/9781316407219. ISBN 978-1-3164-0721-9.

- Leliaert, Frederik; Verbruggen, Heroen; Zechman, Frederick W. (September 2011). "Into the deep: new discoveries at the base of the green plant phylogeny". BioEssays. 33 (9): 683–692. doi:10.1002/bies.201100035. PMID 21744372. S2CID 40459076.

- Leliaert, Frederik; Smith, David R.; Moreau, Hervé; Herron, Matthew D.; Verbruggen, Heroen; Delwiche, Charles F.; De Clerck, Olivier (2012). "Phylogeny and molecular evolution of the green algae" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 31 (1): 1–46. Bibcode:2012CRvPS..31....1L. doi:10.1080/07352689.2011.615705. S2CID 17603352. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-26.

- Lewin, R. A.; Krienitz, L.; Goericke, R.; Takeda, H.; Hepperle, D. (2000). "Picocystis salinarum gen. et sp. nov. (Chlorophyta) – a new picoplanktonic green alga". Phycologia. 39 (6): 560–565. Bibcode:2000Phyco..39..560L. doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-39-6-560.1.

- Lewis, Louise A.; McCourt, Richard M. (2004). "Green algae and the origin of land plants". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1535–1556. Bibcode:2004AmJB...91.1535L. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1535. PMID 21652308.

- Lewis, Louise A.; Lewis, Paul O. (December 2005). "Unearthing the molecular phylodiversity of desert soil green algae (Chlorophyta)". Systematic Biology. 54 (6): 936–947. doi:10.1080/10635150500354852. PMID 16338765.

- Li, Linzhou; Wang, Sibo; Wang, Hongli; Sahu, Sunil Kumar; Marin, Birger; Li, Haoyuan; Xu, Yan; Liang, Hongping; Li, Zhen; Cheng, Shifeng; et al. (September 2020). "The genome of Prasinoderma coloniale unveils the existence of a third phylum within green plants". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (9): 1220–1231. Bibcode:2020NatEE...4.1220L. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1221-7. PMC 7455551. PMID 32572216.

- Lobban CS, Wynne MJ (1981). The Biology of Seaweeds. Botanical Monograph Series 17. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5200-4585-9.

- Lopes dos Santos, Adriana; Pollina, Thibaut; Gourvil, Priscillia; Corre, Erwan; Marie, Dominique; Garrido, José Luis; Rodríguez, Francisco; Noël, Mary-Hélène; Vaulot, Daniel; Eikrem, Wenche (2017). "Chloropicophyceae, a new class of picophytoplanktonic prasinophytes". Sci Rep. 7 (1): 14019. Bibcode:2017NatSR...714019L. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12412-5. PMC 5656628. PMID 29070840.

- López-Bautista, Juan M.; Rindi, Fabio; Guiry, Michael D. (July 2006). "Molecular systematics of the subaerial green algal order Trentepohliales: an assessment based on morphological and molecular data". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 56 (7): 1709–1715. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63990-0. hdl:10379/9448. PMID 16825655.

- Margulis, Lynn; Chapman, Michael J. (2009). "Pr-28 Chlorophyta". Kingdoms & Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth (4th ed.). Academic Press. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-0-1237-3621-5.

- Marin, Birger; Melkonian, Michael (April 2010). "Molecular Phylogeny and Classification of the Mamiellophyceae class. nov. (Chlorophyta) based on Sequence Comparisons of the Nuclear- and Plastid-encoded rRNA Operons". Protist. 161 (2): 304–336. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2009.10.002. PMID 20005168.

- Marin, Birger (2012). "Nested in the Chlorellales or Independent Class? Phylogeny and Classification of the Pedinophyceae (Viridiplantae) Revealed by Molecular Phylogenetic Analyses of Complete Nuclear and Plastid-encoded rRNA Operons". Protist. 163 (5): 778–805. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2011.11.004. PMID 22192529.

- Mattox, K. R.; Stewart, K. D. (1984). "Classification of the Green Algae: A Concept Based on Comparative Cytology". In Irvine, D. E. G.; John, D. M. (eds.). Systematics of the Green Algae. Systematics Association Special. Vol. 27. Academic Press. pp. 29–72. ISBN 0-1237-4040-1.

- Nakayama, Takeshi; Suda, Shoichiro; Kawachi, Masanobu; Inouye, Isao (2007). "Phylogeny and ultrastructure of Nephroselmis and Pseudoscourfieldia (Chlorophyta), including the description of Nephroselmis anterostigmatica sp. nov. and a proposal for the Nephroselmidales ord. nov". Phycologia. 46 (6): 680–697. Bibcode:2007Phyco..46..680N. doi:10.2216/04-25.1.

- Nedelcu, Aurora M. (December 2001). "Complex patterns of plastid 16S rRNA gene evolution in nonphotosynthetic green algae". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 53 (6): 670–679. Bibcode:2001JMolE..53..670N. doi:10.1007/s002390010254. PMID 11677627. S2CID 21151223.

- Nishii, Ichiro; Miller, Stephen M. (2010). "Volvox: Simple steps to developmental complexity?". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 13 (6): 646–653. Bibcode:2010COPB...13..646N. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2010.10.005. PMID 21075047.

- Papenfuss, George F. (1955). "The Classification of the Algae". A century of progress in the natural sciences, 1853-1953. San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences. pp. 115–224.

- Pascher, A. (1914). "Über Flagellaten und Algen". Berichte der Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft. 32: 136–160. doi:10.1111/j.1438-8677.1914.tb07573.x. S2CID 257830577.

- Reichenbach, H. TH. L. (1828). Conspectus Regni Vegetabilis per Gradus Naturales Evoluti. Lipsiae (Leipzig): apud Carolum Cnobloch. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.127418. OCLC 5359726.

- Rockwell, Nathan C.; Martin, Shelley S.; Li, Fay-Wei; Mathews, Sarah; Lagarias, J. Clark (May 2017). "The phycocyanobilin chromophore of streptophyte algal phytochromes is synthesized by HY2". The New Phytologist. 214 (3): 1145–1157. Bibcode:2017NewPh.214.1145R. doi:10.1111/nph.14422. PMC 5388591. PMID 28106912.

- Round, F. E. (1971). "The taxonomy of the Chlorophyta. II". British Phycological Journal. 6 (2): 235–264. doi:10.1080/00071617100650261.

- Smith, Gilbert M. (1938). Cryptogamic Botany. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). McGraw Hill Book Company.

- Solovchenko, Alexei; Merzlyak, Mark N.; Khozin-Goldberg, Inna; Cohen, Zvi; Boussiba, Sammy (2 August 2010). "Coordinated carotenoid and lipid syntheses induced in Parietochloris incisa (Chlorophyta, Trebouxiophyceae) mutant deficient in Δ5 desaturase by nitrogen starvation and high light" (PDF). Journal of Phycology. 46 (4): 763–772. Bibcode:2010JPcgy..46..763S. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2010.00849.x.

- Srivastava, Purnima (2002). "Carbonaceous Megafossils from the Dholpura Shale, Uppermost Vindhyan Supergroup, Rajasthan: An Age Implication" (PDF). Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India. 47 (1): 97–105. Bibcode:2002JPalS..47...97S. doi:10.1177/0971102320020109.

- Tang, Qing; Pang, Ke; Yuan, Xunlai; Xiao, Shuhai (February 2020). "A one-billion-year-old multicellular chlorophyte". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (4): 543–549. Bibcode:2020NatEE...4..543T. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1122-9. PMC 8668152. PMID 32094536.

- Tartar, Aurélien; Boucias, Drion G.; Adams, Byron J.; Becnel, James J. (January 2002). "Phylogenetic analysis identifies the invertebrate pathogen Helicosporidium sp. as a green alga (Chlorophyta)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 52 (1): 273–279. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-1-273. PMID 11837312.

- Umen, James G. (October 2014). "Green algae and the origins of multicellularity in the plant kingdom". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 6 (11) a016170. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016170. PMC 4413236. PMID 25324214.

- van den Hoek, Christiaan; Mann, D. G.; Jahns, H. M. (1995). Algae: An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5213-0419-1.

- Yamaguchi, Haruyo; Suda, Shoichiro; Nakayama, Takeshi; Pienaar, Richard N.; Chihara, Mitsuo; Inouye, Isao (2010). "Taxonomy of Nephroselmis viridis sp. nov. (Nephroselmidophyceae, Chlorophyta), a sister marine species to freshwater N. olivacea". Journal of Plant Research. 124 (1): 49–62. doi:10.1007/s10265-010-0349-y. PMID 20499263.

- Yamashita, Felipe; Baluška, František (2023). "Algal ocelloids and plant ocelli". Plants. 12 (1): 61. doi:10.3390/plants12010061. PMC 9824129. PMID 36616190.

- Yang, Zhiping; Ma, Xiaoya; Wang, Qiuping; Tian, Xiaolin; Sun, Jingyan; Zhang, Zhenhua; Xiao, Shuhai; De Clerck, Olivier; Leliaert, Frederik; Zhong, Bojian (September 2023). "Phylotranscriptomics unveil a Paleoproterozoic-Mesoproterozoic origin and deep relationships of the Viridiplantae". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 5542. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.5542Y. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-41137-5. PMC 10495350. PMID 37696791.

Further reading

[edit]- Burrows EM (1991). Seaweeds of the British Isles. Vol. 2 (Chlorophyta). London: Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-5650-0981-6.

- Pickett-Heaps JD (1975). Green Algae. Structure, Reproduction and Evolution in Selected Genera. Stamford, CT: Sinauer Assoc. p. 606.

Chlorophyta

View on GrokipediaDescription

Cell Structure and Ultrastructure

Chlorophyta exhibit a diverse array of cell types, ranging from unicellular to complex multicellular forms, reflecting their evolutionary adaptability. Unicellular species, such as Chlamydomonas, consist of solitary cells that can be motile or non-motile, while colonial forms like Volvox organize multiple cells into spherical aggregates with division of labor among somatic and reproductive cells. Filamentous types, exemplified by Spirogyra, form unbranched chains of cylindrical cells connected end-to-end, and siphonous structures in genera such as Caulerpa feature coenocytic, multinucleate bodies without cross walls, enabling large, macroscopic thalli.[6][7] The cell wall in Chlorophyta shows significant compositional diversity, typically comprising cellulose microfibrils embedded in a matrix of pectin-like polysaccharides or hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins, which provide structural support and contribute to cell shape variation across taxa. In unicellular and colonial forms, walls are often thin and flexible, whereas in filamentous and siphonous species, they form robust layers that maintain integrity in diverse environments. Some species, particularly in the Ulvophyceae, incorporate scales or a theca—rigid outer coverings made of glycoprotein scales—for protection and motility. Pyrenoids, prominent ultrastructural features within chloroplasts, appear as dense, proteinaceous bodies surrounded by starch granules, serving as sites for starch accumulation and often penetrated by thylakoid membranes for efficient carbon fixation support. Eyespots, or stigmas, consist of stacked carotenoid-rich lipid globules enveloped by chloroplast and plasma membranes, positioned asymmetrically near the anterior end to facilitate phototaxis by shading photoreceptors.[5][5] The flagellar apparatus in motile Chlorophyta cells typically features two to four smooth flagella inserted anteriorly, arising from basal bodies arranged in a cruciate configuration with associated microtubular rootlets that stabilize the cell during swimming. Basal bodies are linked by striated connecting fibers, and transitional fibers extend from their distal ends to anchor the flagella to the cell membrane, ensuring coordinated beating for propulsion. A distinctive multilayered structure (MLS), unique to core Chlorophyta, forms part of the flagellar root system, consisting of three to four parallel lamellae that provide rigidity and are associated with the d- and upper s-rootlets in orders like Ulvophyceae and Trebouxiophyceae. Variations occur across orders: Volvocales display highly organized, motile systems with four flagella in colonial cells for collective movement, whereas Chlorococcales often lack flagella entirely, relying on non-motile zoospores with simplified apparatuses during reproduction.[9][10][11]Chloroplasts and Pigments

Chloroplasts in Chlorophyta are typically bounded by a double membrane envelope, a remnant of their cyanobacterial endosymbiotic origin, and contain thylakoids organized into stacked grana that facilitate efficient light harvesting during photosynthesis.[12] These organelles exhibit diverse morphologies across the division, including discoid, reticulate, or spiral shapes, as seen in genera such as Chlamydomonas where cup-shaped or parietal chloroplasts predominate.[13] The internal structure supports starch storage within the chloroplast stroma, distinguishing Chlorophyta from other algal groups that store reserves in the cytoplasm.[14] The primary photosynthetic pigments in Chlorophyta are chlorophylls a and b, which absorb light in the blue and red wavelengths to drive electron transport, complemented by accessory carotenoids such as β-carotene and lutein, as well as xanthophylls like violaxanthin.[12] These carotenoids protect against photooxidative damage and extend the spectrum of light absorption.[13] Notably, Chlorophyta lack phycobilins, the accessory pigments characteristic of red algae and cyanobacteria, reflecting their distinct evolutionary trajectory within the Viridiplantae.[14] Pyrenoids, prominent proteinaceous structures within the chloroplast stroma, house the enzyme Rubisco and serve as sites for carbon dioxide concentration and starch accumulation in Chlorophyta.[15] They vary in form, including plate-like types bisected by thylakoids or traversed by membrane tubules continuous with the thylakoid network, enhancing CO2 delivery to Rubisco; for example, Chlorella species often feature a single pyrenoid surrounded by a starch sheath composed of two large plates.[16] These structures are enveloped by a sheath of starch granules, which accumulate as the primary photosynthetic product directly in the chloroplast.[17] Chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) in Chlorophyta typically consists of a circular, multi-copy genome, although in some groups such as Cladophorales it is fragmented into linear hairpin chromosomes, encoding genes for photosynthesis, ribosomal components, and RNA polymerase subunits, retained from the ancient cyanobacterial endosymbiont that gave rise to these organelles over a billion years ago.[18][19] Genome sizes vary, but the quadripartite structure with inverted repeats, as in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (approximately 204 kb), is common and supports uniparental inheritance.[20] In kleptoplastidic forms, where certain protists sequester functional Chlorophyta chloroplasts (e.g., from Tetraselmis in Rapaza viridis), these organelles can become reduced in size and gene content while remaining photosynthetically active for extended periods.[21]Metabolism

Chlorophyta, commonly known as green algae, primarily employ C3 photosynthesis, utilizing the Calvin cycle to fix carbon dioxide into organic compounds. In this pathway, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) catalyzes the initial carboxylation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) with CO2, leading to the production of 3-phosphoglycerate as the first stable product. The overall oxygenic photosynthesis process can be represented by the equation: This reaction occurs in the chloroplasts and generates oxygen as a byproduct while producing glucose as the primary carbohydrate.[22][23] Photorespiration in Chlorophyta is biochemically similar to that in C3 higher plants, where RuBisCO's oxygenase activity leads to the formation of 2-phosphoglycolate, which is recycled through a pathway involving peroxisomes and mitochondria, consuming energy and releasing CO2. However, many Chlorophyta species mitigate photorespiration through a CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) that elevates intracellular CO2 levels around RuBisCO, thereby favoring carboxylation over oxygenation.[24][25] Respiration in Chlorophyta occurs via the standard mitochondrial electron transport chain, where electrons from NADH and FADH2 are transferred through complexes I-IV, establishing a proton gradient for ATP synthesis via oxidative phosphorylation. Under aerobic conditions, this process efficiently breaks down carbohydrates and lipids to generate energy. In anaerobic environments, certain species like Chlamydomonas reinhardtii switch to fermentation pathways, producing acetate via pyruvate decarboxylation and subsequent reduction, which regenerates NAD+ for glycolysis continuation. This acetate fermentation allows survival in oxygen-limited habitats, such as sediments or dense blooms.[26][27] Nutrient uptake in Chlorophyta involves active transport mechanisms to acquire essential elements from often dilute aquatic environments. Nitrogen is primarily assimilated as nitrate, reduced by nitrate reductase in the cytoplasm to nitrite and then to ammonium for incorporation into amino acids. Phosphorus is taken up as orthophosphate via high-affinity transporters, supporting ATP and nucleic acid synthesis. For carbon, while CO2 is the preferred form, some species utilize bicarbonate (HCO3-) through plasma membrane transporters, facilitated by external carbonic anhydrase that converts HCO3- to CO2. Osmoregulation is maintained via ion channels and pumps that regulate influx and efflux of ions like K+, Na+, and Cl-, preventing cellular swelling or shrinkage in varying salinities.[28][29] A hallmark of Chlorophyta metabolism is the high accumulation of starch as the primary energy storage compound, synthesized in the chloroplast from glucose-1-phosphate via ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase and starch synthase. This starch serves as a transient reserve, mobilized during darkness or stress. Lipid metabolism is also prominent, particularly triacylglycerols (TAGs) accumulated under nutrient limitation, making species like Chlamydomonas promising for biofuel production through genetic engineering to enhance TAG yields. Carbonic anhydrase enzymes play a critical role in the CCM, rapidly interconverting HCO3- and CO2 to maintain high CO2 availability for RuBisCO, with isoforms localized in the periplasm, thylakoid, and pyrenoid.[30][31][32]Reproduction and Life Cycles

Chlorophyta exhibit a range of asexual reproductive strategies that enable rapid propagation under favorable conditions. Binary fission occurs in unicellular forms such as Chlamydomonas, where the cell divides longitudinally to produce two daughter cells, each inheriting flagella and chloroplasts.[2] Zoospore formation is common in many taxa, with quadriflagellate zoospores released from sporangia in species like Ulothrix, which then germinate into new filaments.[33] Fragmentation, as seen in filamentous Ulothrix, involves the breaking of the filament into segments that each develop into a new individual, often triggered by environmental stress.[34] Sexual reproduction in Chlorophyta varies from primitive to advanced forms, reflecting evolutionary diversification. Isogamy, involving fusion of similar-sized gametes, predominates in unicellular species like Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, where plus (+) and minus (−) mating types ensure compatibility through specific agglutinins on gamete surfaces.[35] Anisogamy features gametes of differing sizes and motility, as in some volvocine algae, while oogamy—the most derived—occurs in colonial Volvox, with large non-motile eggs fertilized by small biflagellate sperm.[2] Zygote formation follows gamete fusion, producing a diploid zygote often encased in a thick, multilayered wall containing sporopollenin for dormancy during adverse conditions, as observed in Chlamydomonas monoica. Parthenogenesis, where unfertilized gametes develop into new individuals, has been documented in ulvophycean species like Ulva prolifera, enhancing reproductive success when mating is limited.[36] Life cycles in Chlorophyta are predominantly haplontic, with the haploid phase dominant and meiosis occurring zygotically in the diploid zygote to restore haploidy. In Chlamydomonas, the zygote undergoes meiosis to yield four haploid zoospores, which develop directly into vegetative cells, exemplifying this pattern.[33] Diplontic cycles, where the diploid phase is dominant, are rare but present in some advanced forms. Alternation of generations appears in taxa like Ulva, featuring isomorphic haploid gametophytes and diploid sporophytes, with meiosis in the sporophyte producing haploid spores that germinate into gametophytes.[33] In volvocine algae such as Volvox, temporary palmelloid stages—non-motile cell aggregates embedded in mucilage—occur during early embryonic development of daughter colonies, facilitating colonial formation before flagella emerge.[37] Gametic meiosis is uncommon, but sporic meiosis supports alternation in ulvophytes. These cycles underscore the phylum's flexibility, with zygotic meiosis being predominant.[2]Ecology

Habitats and Free-Living Forms

Chlorophyta, commonly known as green algae, predominantly inhabit aquatic environments, with a significant majority of species occurring in freshwater systems such as lakes, rivers, and streams. For instance, genera like Cladophora thrive in flowing freshwater habitats, forming dense mats in streams and rivers where they attach to substrates and contribute to benthic communities. In contrast, marine habitats host fewer but often more conspicuous forms, including intertidal and planktonic species; Ulva, known as sea lettuce, is a common example in coastal marine zones, tolerating wave exposure and fluctuating salinities in intertidal pools. Planktonic representatives, such as Volvox, form colonial spheres that float in freshwater bodies, occasionally leading to blooms in nutrient-rich lakes. The majority of species, approximately 90% (~6,200), occur in freshwater habitats, with the remainder (~700) primarily in marine environments, reflecting the division's greater diversity in inland waters.[1] Beyond aquatic settings, free-living Chlorophyta occupy terrestrial and extreme environments, demonstrating remarkable versatility. In soil crusts, unicellular and filamentous forms contribute to biological soil crusts in arid regions, stabilizing surfaces and aiding nutrient cycling. Snow algae, such as Chloromonas species, colonize polar and alpine snowfields, producing red or green pigmentation that protects against high UV radiation during seasonal melts. In geothermal areas, thermotolerant chlorophytes like Chlorella and Coelastrella thermophila var. globulina persist in hot springs, enduring temperatures up to 40–50°C in acidic or neutral waters. These habitats highlight the division's ability to exploit niches beyond water, with terrestrial and extremophilic forms comprising a smaller but ecologically significant portion of the ~6,851 living species.[38][39][40] Adaptations enable Chlorophyta to survive in these diverse free-living conditions, particularly in response to desiccation and salinity stresses. Desiccation tolerance in terrestrial and soil-dwelling species often involves mucilage production, a polysaccharide sheath that retains moisture and shields cells during dry periods, as observed in trebouxiophycean algae on tree bark and rocks. For salinity challenges in marine and brackish habitats, osmolytes such as glycerol accumulate in species like Dunaliella, maintaining cellular turgor and preventing ion toxicity without disrupting photosynthesis. These physiological mechanisms, combined with flexible cell walls, allow free-living chlorophytes to endure environmental fluctuations.[41][42][43] Chlorophyta exhibit a cosmopolitan distribution, with species found across all continents and latitudes, though diversity peaks in tropical regions due to stable warmth and nutrient availability favoring speciation. Higher species richness occurs in tropical freshwater systems, while marine forms show broader latitudinal ranges. Endemism is notable in isolated environments, such as cave systems, where unique lineages of green algae evolve in darkness or low-light conditions, contributing to localized biodiversity hotspots.[44][45][46]Symbiotic Associations

Chlorophyta species, particularly from the Trebouxiophyceae, frequently serve as photobionts in lichen symbioses with ascomycete and basidiomycete fungi. Approximately 90% of lichen-forming fungi associate with green algal photobionts from Chlorophyta, with the genus Trebouxia being the most prevalent, partnering with over 20% of known lichen mycobionts. In these mutualistic relationships, the photobiont performs photosynthesis to supply the fungus with organic carbon compounds, such as glucose, while the fungal partner provides structural protection against desiccation, UV radiation, and herbivores, along with essential minerals and nitrogenous compounds absorbed from the substrate. This nutrient exchange enables lichens to thrive in extreme environments like arid deserts and arctic tundras, where neither partner could survive independently.[47][48][49][50] Beyond lichens, Chlorophyta form photosymbiotic associations with marine and freshwater invertebrates, contrasting with the more famous dinoflagellate Symbiodinium (zooxanthellae) that dominate coral symbioses. True chlorophytes, such as Platymonas convoluta (synonymous with Tetraselmis convolutae), establish intracellular partnerships with acoel flatworms like Convoluta roscoffensis, where the algae provide up to 65% of the host's energy needs through photosynthetic products in exchange for a protected niche and waste recycling. Similarly, in freshwater sponges like Ephydatia muelleri, symbiotic chlorophytes from genera such as Chlorella or Oophila contribute fixed carbon while benefiting from the host's filtration of nutrients and inorganic ions. These interactions often involve horizontal acquisition from the environment, though some exhibit vertical transmission through host gametes, ensuring stable inheritance across generations.[51][52][53][54] Endosymbiotic relationships extend to protists, exemplified by the amoeba Hatena quadrifaria, which harbors a Nephroselmis-like chlorophyte endosymbiont that supports the host's nutrition via photosynthesis during juvenile stages; the alga is vertically transmitted but ultimately ejected during host reproduction to facilitate predatory feeding. In contrast, some Chlorophyta exhibit parasitic tendencies, notably Prototheca species, achlorophyllic members of the Trebouxiophyceae that opportunistically infect humans and cause protothecosis—a rare, often cutaneous or disseminated disease primarily in immunocompromised patients, with over 200 cases reported worldwide since 1952, manifesting as olecranon bursitis, skin ulcers, or systemic involvement. These pathogens enter via traumatic wounds or inhalation, evading immune clearance due to their algal cell wall mimicking fungal structures.[55][56][57] Symbiotic and parasitic Chlorophyta often undergo genomic adaptations, including reduced plastid genomes as seen in Prototheca, where independent losses of photosynthesis across lineages result in compact genomes (28–56 kb) retaining only 19–40 genes, primarily for membrane transport (ycf1, cysT) and essential biosynthesis pathways like fatty acids (accD) and cysteine, reflecting relaxed purifying selection in host-dependent lifestyles. Such reductions enhance metabolic integration with hosts but can facilitate pathogenicity by streamlining resource acquisition. Vertical transmission, observed in associations like green hydra (Hydra viridissima) with Chlorella symbionts, involves symbiont passage through eggs or buds, stabilizing the partnership and promoting co-evolution.[58][59][60]Ecological Roles

Chlorophyta, commonly known as green algae, serve as primary producers in aquatic ecosystems, harnessing sunlight through photosynthesis to convert carbon dioxide and water into organic matter, thereby forming the foundational base of food webs that support herbivores such as zooplankton and higher trophic levels.[61] This role is particularly prominent in freshwater environments, where chlorophytes like Chlorella and Scenedesmus dominate phytoplankton communities and channel energy upward through grazing interactions.[62] By producing oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis, they significantly contribute to the oxygenation of aquatic habitats, maintaining conditions suitable for diverse organisms.[62] In nutrient cycling, the biomass of Chlorophyta plays a dual role: living cells assimilate phosphorus and other nutrients from the water column, while decaying material from senescent or grazed cells releases bound phosphorus back into the system, potentially exacerbating eutrophication in nutrient-enriched waters.[63] For instance, blooms of Chlorella vulgaris in lakes can lead to rapid phosphorus recycling upon decomposition, fueling subsequent algal growth and altering nutrient dynamics.[64] Additionally, macroalgal members of Chlorophyta, such as Ulva species, contribute to carbon sequestration by exporting organic carbon to sediments, where it accumulates and supports long-term storage in coastal and marine environments.[65] Chlorophyta engage in key biotic interactions that shape community structure, including grazing by zooplankton, which can control population sizes and prevent dominance by other phytoplankton, as well as competition with cyanobacteria for light and nutrients under varying carbon dioxide conditions.[66] Green algae often outcompete cyanobacteria in low-CO₂ settings, promoting biodiversity in shallow lakes.[67] They also participate in biofilm formation on submerged surfaces, stabilizing microbial communities and influencing sediment-water interfaces.[68] As indicators of water quality, shifts in chlorophyte abundance and composition reflect trophic status, with increased presence signaling mesotrophic to eutrophic conditions in streams and lakes.[69] Environmental impacts of Chlorophyta include the formation of blooms that drive eutrophication, such as green tides caused by Ulva prolifera, which deplete oxygen through respiration and decay, leading to hypoxic zones harmful to aquatic life.[63] Although most chlorophyte blooms do not release potent toxins like those from dinoflagellates, their proliferation can indirectly promote conditions favoring toxigenic species and degrade habitat quality via excessive biomass accumulation.[64]Systematics

Taxonomic History

The taxonomic history of Chlorophyta traces back to Carl Linnaeus's Species Plantarum (1753), where he classified green algae under the informal grouping "Algae virides" within the broader class Cryptogamia, encompassing various simple aquatic plants based on their green coloration and lack of obvious reproductive structures.[70] This early system treated algae as a heterogeneous assemblage, often lumping them with mosses and fungi due to limited morphological resolution available at the time. Linnaeus's approach relied on gross morphology and habitat, providing a foundational but broad categorization that included many filamentous and unicellular forms now recognized as chlorophytes.[71] In the 19th century, more detailed classifications emerged as botanists like Carl Adolf Agardh advanced the field through his multi-volume Species Algarum (1817–1824, 1824–1828), dividing green algae into families and orders such as Confervoideae and Ulvaceae based on thallus organization, branching patterns, and habitat preferences. Similarly, Ludwig Rabenhorst's Kryptogamen-Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz (1848–1888) organized chlorophytes into orders like Confervales, emphasizing filamentous and branched forms observable under early microscopes, which allowed for better differentiation among freshwater and marine species. Ferdinand Cohn contributed significantly in 1854 with his Untersuchungen über die Entwicklungsgeschichte der mikroskopischen Algen und Pilze, where he separated green algae from Cyanobacteria (then called blue-green algae) by documenting their distinct reproductive cycles and cellular development, highlighting the presence of true nuclei and sexual reproduction in chlorophytes via light microscopy.[72] These efforts marked a shift toward developmental and cytological criteria, though challenges persisted due to superficial similarities in color and simplicity between green algae and prokaryotic Cyanobacteria, often leading to misclassifications in earlier works. The pre-molecular era's heavy reliance on morphology, observed through improving light microscopy, drove key developments in the 20th century. F.E. Fritsch's seminal The Structure and Reproduction of the Algae (Volume 1, 1935) formally recognized Chlorophyceae as a distinct class within Chlorophyta, integrating ultrastructural details like chloroplast arrangement and flagellar characteristics to delineate it from other algal groups.[73] This work synthesized prior observations, addressing longstanding confusions by stressing reproductive modes—such as isogamy and oogamy—as diagnostic traits. Later milestones included Gilbert M. Smith's The Fresh-Water Algae of the United States (2nd edition, 1950), which revised classifications by prioritizing thallus types (e.g., unicellular, siphoneous, and multicellular), providing a practical framework for identifying over 3,000 North American species and underscoring morphological variability as a core organizing principle.[74] These systems, while influential, highlighted the limitations of phenotype-based taxonomy in resolving deeper affinities among diverse chlorophyte lineages.Modern Classification

In contemporary taxonomy, the division Chlorophyta (green algae) is defined as a monophyletic group within the kingdom Plantae, specifically the subkingdom Viridiplantae, encompassing all green algae except those in the sister division Streptophyta (which includes charophyte algae and embryophytes).[75] This classification integrates morphological characteristics, such as cell wall composition and flagellar apparatus, with molecular data from nuclear, plastid, and mitochondrial genes. The International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN) governs the naming of Chlorophyta taxa. Chlorophyta comprises approximately 1,513 genera and 6,851 extant species, representing a diverse assemblage primarily adapted to freshwater, marine, and terrestrial environments.[76] The core of Chlorophyta, often termed the UTC clade, consists of three major monophyletic classes that account for the majority of species diversity: Chlorophyceae, Ulvophyceae, and Trebouxiophyceae. Chlorophyceae, the largest class with about 3,974 extant species, includes unicellular to colonial forms and is characterized by a counterclockwise flagellar apparatus in motile cells; key orders include Sphaeropleales (e.g., desmids and hydrodictyacean algae), Chlamydomonadales (e.g., Chlamydomonas), and Oedogoniales (filamentous forms like Oedogonium).[76][13] Ulvophyceae, with roughly 1,705 extant species, features siphonous and multinucleate forms alongside simpler filaments, with prominent orders such as Ulotrichales (e.g., Ulothrix) and Ulvales (e.g., sea lettuces like Ulva).[76][13] Trebouxiophyceae, comprising around 925 extant species, often includes non-motile, coccoid cells and symbiotic forms, with the order Trebouxiales (e.g., Chlorella and Trebouxia) being representative.[76][13] Additional classes within Chlorophyta include several smaller, early-diverging lineages, many derived from the paraphyletic prasinophytes—flagellated algae that represent primitive green algal forms. These comprise Pyramimonadophyceae (107 extant species, e.g., order Pyramimonadales with scaled flagellates like Pyramimonas), Chlorodendrophyceae (45 extant species, e.g., Chlorodendron), Mamiellophyceae (25 extant species, e.g., Micromonas in marine picophytoplankton), Pedinophyceae (24 extant species, recently elevated from prasinophyte status, e.g., Pedinomonas), and Nephroselmidophyceae (29 extant species), along with even smaller classes like Chloropicophyceae (8 extant species) and Picocystophyceae (1 extant species).[76][75] Prasinophytes as a whole are polyphyletic, with their lineages branching basally to the core Chlorophyta and contributing to the division's overall paraphyly in broader historical senses before modern refinements.[77] Streptophyta is consistently excluded from Chlorophyta in current schemes, forming a separate monophyletic division that includes basal classes like Chlorokybophyceae (e.g., Chlorokybus) and Klebsormidiophyceae (e.g., Klebsormidium), which are streptophyte-specific and not part of the chlorophyte radiation.[75] Recent taxonomic revisions, such as the recognition of Pedinophyceae, reflect ongoing integration of phylogenomic data to refine class boundaries.[78] Overall, Chlorophyta's 11 recognized classes highlight its evolutionary depth, with the core UTC classes dominating in species richness and ecological impact.[76]Phylogenetic Relationships

Phylogenetic analyses of Chlorophyta have relied heavily on molecular markers such as the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene and the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (rbcL) gene, which consistently recover the monophyly of the core Chlorophyta clade comprising Ulvophyceae, Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyceae, Pedinophyceae, and Chlorodendrophyceae.[79] These markers reveal a paraphyletic assemblage of early-diverging prasinophyte lineages at the base of Chlorophyta, which gave rise to the more derived core groups through successive branching events.[79] Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of rDNA have proven useful for resolving relationships at the species and genus levels within these lineages, complementing broader phylogenies.[75] The prasinophytes, characterized by their simple, often scaly flagellated cells, are polyphyletic and distributed across multiple basal clades within Chlorophyta, underscoring their role as ancestral forms rather than a cohesive group.[18] For instance, the order Mamiellales (now classified under Mamiellophyceae) represents one of the earliest diverging branches, supported by chloroplast genome data showing distinct structural features and early separation from other prasinophyte lineages.[18] Other basal prasinophyte groups, such as the Prasinococcales and Palmophyllales, further illustrate this polyphyly, with phylogenies placing them as successive outgroups to the core Chlorophyta.[18] A comprehensive phylogeny based on multi-gene analyses confirms these relationships, highlighting the transition from planktonic prasinophyte ancestors to the diverse morphologies of core chlorophytes.[79] Ultrastructural characters provide key synapomorphies for major clades within core Chlorophyta, particularly the UTC assemblage (Ulvophyceae, Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyceae), which is unified by the presence of a multi-layered structure (MLS) in the flagellar transitional region and a counterclockwise orientation of the flagellar basal bodies.[80] These features, absent in most prasinophytes, mark the evolutionary innovation that defines the UTC clade and distinguishes it from earlier branches.[80] Pedinophyceae and Chlorodendrophyceae occupy intermediate positions, sharing some phycoplast-mediated cell division traits with UTC but lacking the full suite of MLS characteristics.[81] Recent advances in phylogenomics, including analyses of complete chloroplast genomes and nuclear transcriptomes from over 70 species, have resolved previously ambiguous deep nodes within core Chlorophyta, confirming the sequential branching of Pedinophyceae, Chlorodendrophyceae, and UTC with high support.[81] For example, nuclear phylogenomic studies from 2025 using 844 genes across 93 core Chlorophyta taxa have further clarified the position of early prasinophyte offshoots and reinforced the polyphyletic nature of prasinophytes, addressing prior incompletenesses in multi-gene trees.[82] These genomic approaches highlight the ancient diversification of Chlorophyta and provide a robust framework for understanding trait evolution, such as the loss of flagella in many derived lineages.[81]Evolution

Origins and Early Diversification

The origins of Chlorophyta are rooted in the primary endosymbiotic event that established the Archaeplastida supergroup, wherein a heterotrophic eukaryotic host engulfed a cyanobacterial endosymbiont to form the progenitor of all primary plastids.[83] This event is estimated to have occurred approximately 2.0 billion years ago during the Paleoproterozoic Era, marking the advent of oxygenic photosynthesis in eukaryotic lineages.[84] Within Archaeplastida, the Viridiplantae (green plants, encompassing Chlorophyta and Streptophyta) emerged as one of the three primary lineages alongside Rhodophyta and Glaucophyta, with the green algal plastid retaining characteristics such as chlorophylls a and b, distinct from the chlorophyll a-only systems in other groups.[85] The early divergence of Chlorophyta from its sister clade, Streptophyta (which includes embryophytes), occurred within the Viridiplantae, sharing ancestral traits such as phragmoplast-mediated cell division that facilitated cytokinesis in the common green algal ancestor.[86] Molecular clock analyses, calibrated with fossil constraints, place this Viridiplantae split around 1,200–1,000 million years ago (Mya), with the crown group of Chlorophyta radiating subsequently in the Neoproterozoic Era approximately 800 Mya.[87] This timing aligns with environmental shifts, including rising atmospheric oxygenation during the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event (circa 800–500 Mya), which likely promoted diversification by alleviating oxygen stress on early photosynthetic eukaryotes.[88] Initial diversification of Chlorophyta is exemplified by basal lineages such as the prasinophytes, a paraphyletic assemblage of unicellular, flagellated forms that represent the earliest-branching clades and exhibit primitive traits like simple thylakoid organization.[75] These groups emerged in the Mesoproterozoic, transitioning from freshwater to marine habitats and adapting to varying salinities, as inferred from biomarker and phylogenetic evidence.[87] Post-2020 molecular clock studies, incorporating expanded genomic datasets, have refined this pre-Cambrian timeline, confirming crown Chlorophyta origins near 1,000 Mya and highlighting the role of serial endosymbiotic gene transfers in stabilizing early plastid function.[89]Fossil Record

The fossil record of Chlorophyta is sparse and biased toward forms with calcified or resistant structures, as many green algae possess soft, unmineralized thalli that decay rapidly and rarely preserve.[90] The earliest potential evidence comes from Proterozoic macrofossils like Grypania spiralis, spiral-shaped structures up to 60 cm long interpreted as possible eukaryotic algae from the 2.1-billion-year-old Negaunee Iron-Formation in Michigan, though its affinity to Chlorophyta remains debated due to limited cellular detail.[91] More definitive chlorophyte fossils appear in the Mesoproterozoic, such as Proterocladus antiquus, a multicellular, branched green seaweed from ~1 billion-year-old deposits in China's Chuanlinggou Formation, representing one of the oldest records of complex chlorophyte morphology with filaments up to 2 mm long. In the Neoproterozoic and Ediacaran (~635–541 Ma), macroalgal fossils become more diverse, though unambiguous Chlorophyta are limited; examples include probable benthic macroalgae from the Ediacara Member in South Australia and a stem-group Codium-like coenocytic alga from the latest Ediacaran Dengying Formation in South China, featuring spherical cells ~100–200 μm in diameter preserved in phosphate.[92][93] The Paleozoic record expands with marine dasycladalean algae, calcareous chlorophytes known from the Silurian onward, including Carboniferous species like Gyliakiea and Pseudogoniolina that formed segmented thalli up to several centimeters, contributing to shallow-marine carbonate platforms.[94] Devonian examples include colonial volvocalean chlorophytes such as Eovolvox silesiensis from Polish lagoonal deposits, preserved as spherical colonies of 8–16 cells ~50 μm in diameter via carbonate permineralization.[95] The Mesozoic and Cenozoic show increased abundance of calcareous chlorophytes, particularly in tropical reefs; Halimeda species, with their segmented, calcified blades, first appear in the Cretaceous but diversified significantly in the Eocene, forming extensive bioherms in Indo-Pacific platforms as evidenced by fossil segments up to 10 cm long in Eocene limestones of Egypt and the Caribbean.[90] Taphonomic biases, including poor preservation of non-calcifying forms and overrepresentation of dasycladaleans due to their aragonitic skeletons, result in an incomplete record, with molecular biomarkers like C29 steranes suggesting a more ancient and diverse chlorophyte presence than body fossils indicate.[96] Recent discoveries, such as the 2020 description of Proterocladus and 2022 Ediacaran Codium-like fossils, alongside Proterozoic biomarker analyses revealing protosterol distributions consistent with early green algal diversification, continue to fill gaps in the temporal distribution of Chlorophyta.[93]Relationship to Embryophytes

The streptophyte clade unites charophyte green algae—such as those in the orders Charales, Coleochaetales, and Zygnematales—with land plants (Embryophyta), forming a monophyletic group within the green plants (Viridiplantae) that is supported by multigene phylogenetic analyses of nuclear-encoded proteins.[97] These analyses, incorporating hundreds of nuclear genes, consistently position charophytes as the closest algal relatives to embryophytes, with Zygnematophyceae emerging as the immediate sister group in recent phylogenomic studies.[98] This relationship underscores the evolutionary continuity between aquatic algal ancestors and terrestrial plants, distinct from the more distant core chlorophyte algae. Several cellular and molecular traits shared exclusively between charophytes and embryophytes highlight their common ancestry. Phragmoplast-mediated cytokinesis, involving a microtubule array that guides cell plate formation during cell division, is present in advanced charophytes like Chara and Coleochaete, as well as all land plants, but absent in core chlorophytes.[99] Similarly, rosette-shaped cellulose synthase complexes (CSCs), which assemble cellulose microfibrils in a linear fashion at the plasma membrane, characterize charophyte green algae and embryophytes, contrasting with the linear terminal complexes found in chlorophytes.[100] Additionally, transcription factors of the AP2/ERF family, which regulate developmental processes and stress responses, are conserved across streptophytes, with phylogenetic evidence tracing their origin to a pre-land plant ancestor in the charophyte lineage.[101] Key divergences between streptophytes and embryophytes include differences in life cycle strategies. While embryophytes exhibit alternation of generations featuring multicellular haploid gametophytes and diploid sporophytes—often with sporophyte dominance—most charophytes and chlorophytes maintain a haplontic life cycle dominated by the haploid phase, with meiosis occurring immediately after zygote formation and no extended multicellular diploid stage.[102] This innovation in embryophytes facilitated adaptation to terrestrial environments. The divergence of embryophytes from their charophyte algal ancestors within Streptophyta is estimated to have occurred approximately 470 million years ago during the Ordovician-Silurian transition, based on molecular clock analyses calibrated with fossil evidence.[86] Post-2020 genomic comparisons have further resolved evolutionary dynamics, including gene transfers that shaped streptophyte diversification. For instance, analyses of the Chara braunii genome alongside liverwort genomes like Marchantia polymorpha have revealed conserved gene clusters and pathways, while broader surveys document episodes of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from bacteria and fungi into charophytes and early land plants, contributing to metabolic innovations such as specialized secondary compound biosynthesis.[103][104] Recent genomic analyses of Zygnema (2024) have identified key genes involved in stress responses and cell wall modifications that bridge algal and land plant adaptations.[105] These HGT events, peaking in frequency during the bryophyte phase, underscore how genetic exchanges complemented vertical inheritance in the transition to land.[106]Uses and Significance

Model Organisms

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii serves as a prominent model organism in Chlorophyta research, particularly for studies on flagellar motility, chloroplast genetics, and photosynthetic processes. This unicellular green alga has facilitated breakthroughs in understanding eukaryotic flagella assembly and function due to its two anterior flagella, which enable detailed genetic and biochemical analyses.[107] Its chloroplast genome has been instrumental in elucidating organelle inheritance and transformation techniques, with early work demonstrating efficient chloroplast DNA integration via biolistic methods.[108] The complete nuclear genome of C. reinhardtii was sequenced in 2007, revealing evolutionary insights into metabolic pathways shared with plants and animals, and enabling subsequent genetic manipulations. More recently, CRISPR-Cas9 systems have been adapted for precise genome editing in C. reinhardtii, allowing targeted disruptions in genes related to phototaxis and lipid metabolism.[109] Volvox carteri is widely employed as a model for investigating the evolution of multicellularity and developmental biology within Chlorophyta. This colonial alga exhibits a simple germ-soma differentiation, with somatic cells specialized for motility and gonidia for reproduction, providing an accessible system to study cell fate determination.[110] Genomic analyses have identified genes specifically expressed in somatic cells, highlighting the minimal genetic changes required for multicellular complexity compared to unicellular relatives like Chlamydomonas.[111] These findings have informed models of developmental signaling pathways, including the role of the regA gene in repressing reproductive programs in somatic cells.[112] Chlorella vulgaris functions as a key model for nutrient uptake dynamics and stress response mechanisms in algal physiology. It has been used to model phosphate and nitrogen assimilation under varying environmental conditions, demonstrating efficient uptake rates that inform bioremediation strategies.[113] Studies on C. vulgaris reveal adaptive responses to abiotic stresses, such as salinity and nutrient limitation, involving upregulation of antioxidant enzymes and lipid accumulation.[114] Additionally, NASA experiments have utilized C. vulgaris in photobioreactors to simulate life support systems, testing its oxygen production and biomass growth under microgravity and elevated CO2 levels.[115] Other Chlorophyta species contribute to specialized research areas, with Ostreococcus tauri recognized as the smallest free-living eukaryote and a model for viral-host interactions. Its compact genome (approximately 13 Mb) and minimal cellular complexity make it ideal for studying prasinovirus infection dynamics and antiviral defenses, including giant virus resistance mechanisms.[116] Chlorophyta have been employed as model organisms since the late 19th century, with early microscopic studies on species like Volvox paving the way for modern genetic and physiological investigations.[117]Industrial Applications