Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aptamer

View on Wikipedia

Aptamers are oligomers of artificial ssDNA, RNA, XNA, or peptide that bind a specific target molecule, or family of target molecules. They exhibit a range of affinities (KD in the pM to μM range),[1][2] with variable levels of off-target binding[3] and are sometimes classified as chemical antibodies. Aptamers and antibodies can be used in many of the same applications, but the nucleic acid-based structure of aptamers, which are mostly oligonucleotides, is very different from the amino acid-based structure of antibodies, which are proteins. This difference can make aptamers a better choice than antibodies for some purposes (see antibody replacement).

Aptamers are used in biological lab research and medical tests. If multiple aptamers are combined into a single assay, they can measure large numbers of different proteins in a sample. They can be used to identify molecular markers of disease, or can function as drugs, drug delivery systems and controlled drug release systems. They also find use in other molecular engineering tasks.

Most aptamers originate from SELEX, a family of test-tube experiments for finding useful aptamers in a massive pool of different DNA sequences. This process is much like natural selection, directed evolution or artificial selection. In SELEX, the researcher repeatedly selects for the best aptamers from a starting DNA library made of about a quadrillion different randomly generated pieces of DNA or RNA. After SELEX, the researcher might mutate or change the chemistry of the aptamers and do another selection, or might use rational design processes to engineer improvements. Non-SELEX methods for discovering aptamers also exist.

Researchers optimize aptamers to achieve a variety of beneficial features. The most important feature is specific and sensitive binding to the chosen target. When aptamers are exposed to bodily fluids, as in serum tests or aptamer therapeutics, it is often important for them to resist digestion by DNA- and RNA-destroying enzymes. Therapeutic aptamers often must be modified to clear slowly from the body. Aptamers that change their shape dramatically when they bind their target are useful as molecular switches to turn a sensor on and off. Some aptamers are engineered to fit into a biosensor or in a test of a biological sample. It can be useful in some cases for the aptamer to accomplish a pre-defined level or speed of binding. As the yield of the synthesis used to produce known aptamers shrinks quickly for longer sequences,[4] researchers often truncate aptamers to the minimal binding sequence to reduce the production cost.

Etymology

[edit]The word "aptamer" is a neologism coined by Andrew D. Ellington and Jack Szostak in their first publication on the topic. They did not provide a precise definition, stating "We have termed these individual RNA sequences 'aptamers', from the Latin aptus, to fit."[5]

The word itself, however, derives from the Greek word ἅπτω, to connect or fit (as used by Homer (c. 8th century BC)[6][7]) and μέρος, a component of something larger.[8]

Classification

[edit]A typical aptamer is a synthetically generated ligand exploiting the combinatorial diversity of DNA, RNA, XNA, or peptide to achieve strong, specific binding for a particular target molecule or family of target molecules. Aptamers are occasionally classified as "chemical antibodies" or "antibody mimics".[9] However, most aptamers are small, with a molecular weight of 6-30 kDa, in contrast to the 150 kDa size of antibodies, and contain one binding site rather than the two matching antigen binding regions of a typical antibody.

History

[edit]

Since its first application in 1967,[10] directed evolution methodologies have been used to develop biomolecules with new properties and functions. Early examples include the modification of the bacteriophage Qbeta replication system and the generation of ribozymes with modified cleavage activity.[11]

In 1990, two teams independently developed and published SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment) methods and generated RNA aptamers: the lab of Larry Gold, using the term SELEX for their process of selecting RNA ligands against T4 DNA polymerase[12] and the lab of Jack Szostak, selecting RNA ligands against various organic dyes.[5][13] Two years later, the Szostak lab and Gilead Sciences, acting independently of one another, used in vitro selection schemes to generate DNA aptamers for organic dyes[14] and human thrombin,[15] respectively. In 2001, SELEX was automated by J. Colin Cox in the Ellington lab, reducing the duration of a weeks-long selection experiment to just three days.[16][17][18]

In 2002, two groups led by Ronald Breaker and Evgeny Nudler published the first definitive evidence for a riboswitch, a nucleic acid-based genetic regulatory element, the existence of which had previously been suspected. Riboswitches possess similar molecular recognition properties to aptamers. This discovery added support to the RNA World hypothesis, a postulated stage in time in the origin of life on Earth.[19]

Properties

[edit]Structure

[edit]

Most aptamers are based on a specific oligomer sequence of 20-100 bases and 3-20 kDa. Some have chemical modifications for functional enhancements or compatibility with larger engineered molecular systems. DNA, RNA, XNA, and peptide aptamer chemistries can each offer distinct profiles in terms of shelf stability, durability in serum or in vivo, specificity and sensitivity, cost, ease of generation, amplification, and characterization, and familiarity to users. Typically, DNA- and RNA-based aptamers exhibit low immunogenicity, are amplifiable via Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), and have complex secondary structure and tertiary structure.[20][21][22][23] DNA- and XNA-based aptamers exhibit superior shelf stability. XNA-based aptamers can introduce additional chemical diversity to increase binding affinity or greater durability in serum or in vivo.

As 22 genetically encoded and over 500 naturally occurring amino acids exist, peptide aptamers, as well as antibodies, have much greater potential combinatorial diversity per unit length relative to the 4 nucleic acids in DNA or RNA.[24] Chemical modifications of nucleic acid bases or backbones increase the chemical diversity of standard nucleic acid bases.[25]

Split aptamers are composed of two or more DNA strands that are pieces of a larger parent aptamer that has been broken in two by a molecular nick.[26] The ability of each component strand to bind targets will depend on the location of the nick, as well as the secondary structures of the daughter strands.[27] The presence of a target molecule supports the joining of DNA fragments. This can be used as the basis for biosensors.[28] Once assembled, the two separate DNA strands can be ligated into a single strand.

Unmodified aptamers are cleared rapidly from the bloodstream, with a half-life of seconds to hours. This is mainly due to nuclease degradation, which physically destroys the aptamers, as well as clearance by the kidneys, a result of the aptamer's low molecular weight and size. Several modifications, such as 2'-fluorine-substituted pyrimidines and polyethylene glycol (PEG) linkage, permit a serum half-life of days to weeks. PEGylation can add sufficient mass and size to prevent clearance by the kidneys in vivo. Unmodified aptamers can treat coagulation disorders. The problem of clearance and nuclease digestion is diminished when they are applied to the eye, where there is a lower concentration of nuclease and the rate of clearance is lower.[29] Rapid clearance from serum can also be useful in some applications, such as in vivo diagnostic imaging.[30]

In a study on aptamers[31] designed to bind with proteins associated with Ebola infection, a comparison was made among three aptamers isolated for their ability to bind the target protein EBOV sGP. Although these aptamers vary in both sequence and structure, they exhibit remarkably similar relative affinities for sGP from EBOV and SUDV, as well as EBOV GP1.2. Notably, these aptamers demonstrated a high degree of specificity for the GP gene products. One aptamer, in particular, proved effective as a recognition element in an electrochemical sensor, enabling the detection of sGP and GP1.2 in solution, as well as GP1.2 within a membrane context.The results of this research point to the intriguing possibility that certain regions on protein surfaces may possess aptatropic qualities. Identifying the key features of such sites, in conjunction with improved 3-D structural predictions for aptamers, holds the potential to enhance the accuracy of predicting aptamer interaction sites on proteins. This, in turn, may help identify aptamers with a heightened likelihood of binding proteins with high affinity, as well as shed light on protein mutations that could significantly impact aptamer binding.This comprehensive understanding of the structure-based interactions between aptamers and proteins is vital for refining the computational predictability of aptamer-protein binding. Moreover, it has the potential to eventually eliminate the need for the experimental SELEX protocol.

Targets

[edit]Aptamer targets can include small molecules and heavy metal ions, larger ligands such as proteins, and even whole cells.[32][33] These targets include lysozyme,[34] thrombin,[35][36] human immunodeficiency virus trans-acting responsive element (HIV TAR),[37] hemin,[38] interferon γ,[39] vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF),[40][41] prostate specific antigen (PSA),[42][43] dopamine,[44] and the non-classical oncogene, heat shock factor 1 (HSF1).[45]

Aptamers have been generated against cancer cells,[46] prions,[47] bacteria,[48] and viruses. Viral targets of aptamers include influenza A and B viruses,[49] Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV),[49] SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV)[49] and SARS-CoV-2.[50]

Aptamers may be particularly useful for environmental science proteomics.[51] Antibodies, like other proteins, are more difficult to sequence than nucleic acids. They are also costly to maintain and produce, and are at constant risk of contamination, as they are produced via cell culture or are harvested from animal serum. For this reason, researchers interested in little-studied proteins and species may find that companies will not produce, maintain, or adequately validate the quality of antibodies against their target of interest.[52] By contrast, aptamers are simple to sequence and cost nothing to maintain, as their exact structure can be stored digitally and synthesized on demand. This may make them more economically feasible as research tools for underfunded biological research subjects. Aptamers exist for plant compounds, such as theophylline (found in tea)[53] and abscisic acid (a plant immune hormone).[54] An aptamer against a-amanitin (the toxin that causes lethal Amanita poisoning) has been developed, an example of an aptamer against a mushroom target.[55]

Aptamer applications can be roughly grouped into sensing, therapeutic, reagent production, and engineering categories. Sensing applications are important in environmental, biomedical, epidemiological, biosecurity, and basic research applications, where aptamers act as probes in assays, imaging methods, diagnostic assays, and biosensors.[32][56][57][58][59][60] In therapeutic applications and precision medicine, aptamers can function as drugs,[61] as targeted drug delivery vehicles,[62] as controlled release mechanisms, and as reagents for drug discovery via high-throughput screening for small molecules[63] and proteins.[64][65] Aptamers have application for protein production monitoring, quality control, and purification.[66][67][68] They can function in molecular engineering applications as a way to modify proteins, such as enhancing DNA polymerase to make PCR more reliable.[69][70][71][72]

Because the affinity of the aptamer also affects its dynamic range and limit of detection, aptamers with a lower affinity may be desirable when assaying high concentrations of a target molecule.[73] Affinity chromatography also depends on the ability of the affinity reagent, such as an aptamer, to bind and release its target, and lower affinities may aid in the release of the target molecule.[74] Hence, specific applications determine the useful range for aptamer affinity.

Antibody replacement

[edit]Aptamers can replace antibodies in many biotechnology applications.[75][52] In laboratory research and clinical diagnostics, they can be used in aptamer-based versions of immunoassays including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA),[76] western blot,[77] immunohistochemistry (IHC),[78] and flow cytometry.[79] As therapeutics, they can function as agonists or antagonists of their ligand.[80] While antibodies are a familiar technology with a well-developed market, aptamers are a relatively new technology to most researchers, and aptamers have been generated against only a fraction of important research targets.[81] Unlike antibodies, unmodified aptamers are more susceptible to nuclease digestion in serum and renal clearance in vivo. Aptamers are much smaller in size and mass than antibodies, which could be a relevant factor in choosing which is best suited for a given application. When aptamers are available for a particular application, their advantages over antibodies include potentially lower immunogenicity, greater replicability and lower cost, a greater level of control due to the in vitro selection conditions, and capacity to be efficiently engineered for durability, specificity, and sensitivity.[82]

In addition, aptamers contribute to reduction of research animal use.[83] While antibodies often rely on animals for initial discovery, as well as for production in the case of polyclonal antibodies, both the selection and production of aptamers is typically animal-free. However, phage display methods allow for selection of antibodies in vitro, followed by production from a monoclonal cell line, avoiding the use of animals entirely.[84]

Controlled release of therapeutics

[edit]The ability of aptamers to reversibly bind molecules such as proteins has generated increasing interest in using them to facilitate controlled release of therapeutic biomolecules, such as growth factors. This can be accomplished by tuning the binding strength to passively release the growth factors,[85] along with active release via mechanisms such as hybridization of the aptamer with complementary oligonucleotides[86] or unfolding of the aptamer due to cellular traction forces.[87]

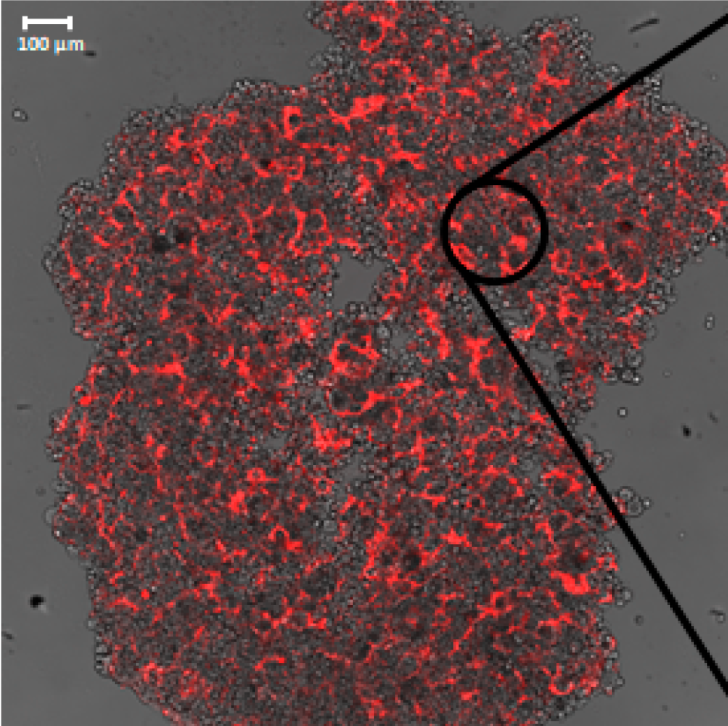

Tissue Engineering Application

[edit]Aptamer, known for their ability to bind specific molecules reversibly, have been used in 3D bioprinting tissues to precisely deliver growth factors to promote vascularization.[88][89] This controlled delivery allows growth factors to be released at the right place and time, encouraging the formation of localized and complex vascular networks. Additionally, the properties of these networks can be fine-tuned by adjusting how growth factors are released over time, making this approach a powerful tool for creating vascularized engineered tissues.

AptaBiD

[edit]AptaBiD (Aptamer-Facilitated Biomarker Discovery) is an aptamer-based method for biomarker discovery.[90]

Peptide Aptamers

[edit]While most aptamers are based on DNA, RNA, or XNA, peptide aptamers[91] are artificial proteins selected or engineered to bind specific target molecules.

Structure

[edit]Peptide aptamers consist of one or more peptide loops of variable sequence displayed by a protein scaffold. Derivatives known as tadpoles, in which peptide aptamer "heads" are covalently linked to unique sequence double-stranded DNA "tails", allow quantification of scarce target molecules in mixtures by PCR (using, for example, the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction) of their DNA tails.[92] The peptides that form the aptamer variable regions are synthesized as part of the same polypeptide chain as the scaffold and are constrained at their N and C termini by linkage to it. This double structural constraint decreases the diversity of the 3D structures that the variable regions can adopt,[93] and this reduction in structural diversity lowers the entropic cost of molecular binding when interaction with the target causes the variable regions to adopt a uniform structure.

Selection

[edit]The most common peptide aptamer selection system is the yeast two-hybrid system. Peptide aptamers can also be selected from combinatorial peptide libraries constructed by phage display and other surface display technologies such as mRNA display, ribosome display, bacterial display and yeast display. These experimental procedures are also known as biopanning. All the peptides panned from combinatorial peptide libraries have been stored in the MimoDB database.[94][95]

Applications

[edit]Libraries of peptide aptamers have been used as "mutagens", in studies in which an investigator introduces a library that expresses different peptide aptamers into a cell population, selects for a desired phenotype, and identifies those aptamers that cause the phenotype. The investigator then uses those aptamers as baits, for example in yeast two-hybrid screens to identify the cellular proteins targeted by those aptamers. Such experiments identify particular proteins bound by the aptamers, and protein interactions that the aptamers disrupt, to cause the phenotype.[96][97] In addition, peptide aptamers derivatized with appropriate functional moieties can cause specific post-translational modification of their target proteins, or change the subcellular localization of the targets.[98]

Industry and Research Community

[edit]Commercial products and companies based on aptamers include the drug Macugen (pegaptanib)[99] and the clinical diagnostic company SomaLogic.[100] The International Society on Aptamers (INSOAP), a professional society for the aptamer research community, publishes a journal devoted to the topic, Aptamers. Apta-index[101] is a current database cataloging and simplifying the ordering process for over 700 aptamers.

See also

[edit]- Anti-thrombin aptamers – Oligonucleotides which recognize the exosites of human thrombin

- Deoxyribozyme – DNA oligonucleotides that can perform a specific chemical reaction

- Synthetic antibody – Affinity reagents generated entirely in vitro

References

[edit]- ^ Rhodes, Andrew; Smithers, Nick; Chapman, Trevor; Parsons, Sarah; Rees, Stephen (2001-10-05). "The generation and characterisation of antagonist RNA aptamers to MCP-1". FEBS Letters. 506 (2): 85–90. Bibcode:2001FEBSL.506...85R. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02895-2. ISSN 0014-5793. PMID 11591377. S2CID 36797240.

- ^ Stoltenburg, Regina; Nikolaus, Nadia; Strehlitz, Beate (2012-12-30). "Capture-SELEX: Selection of DNA Aptamers for Aminoglycoside Antibiotics". Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry. 2012 e415697. doi:10.1155/2012/415697. ISSN 2090-8865. PMC 3544269. PMID 23326761.

- ^ Crivianu-Gaita V, Thompson M (November 2016). "Aptamers, antibody scFv, and antibody Fab' fragments: An overview and comparison of three of the most versatile biosensor biorecognition elements". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 85: 32–45. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2016.04.091. PMID 27155114.

- ^ "DNA Oligonucleotide Synthesis". Millipore Sigma. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ a b Ellington AD, Szostak JW (August 1990). "In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands". Nature. 346 (6287): 818–822. Bibcode:1990Natur.346..818E. doi:10.1038/346818a0. PMID 1697402. S2CID 4273647.

- ^ "ἅπτω", Βικιλεξικό (in Greek), 2023-03-12, retrieved 2024-03-21

- ^ "Οδύσσεια/φ - Βικιθήκη". el.wikisource.org (in Greek). Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ "μέρος", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 2023-05-31, retrieved 2024-03-21

- ^ Zhou G, Wilson G, Hebbard L, Duan W, Liddle C, George J, Qiao L (March 2016). "Aptamers: A promising chemical antibody for cancer therapy". Oncotarget. 7 (12): 13446–13463. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.7178. PMC 4924653. PMID 26863567. S2CID 16618423.

- ^ Mills DR, Peterson RL, Spiegelman S (July 1967). "An extracellular Darwinian experiment with a self-duplicating nucleic acid molecule". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 58 (1): 217–224. Bibcode:1967PNAS...58..217M. doi:10.1073/pnas.58.1.217. PMC 335620. PMID 5231602.

- ^ Joyce GF (October 1989). "Amplification, mutation and selection of catalytic RNA". Gene. 82 (1): 83–87. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(89)90033-4. PMID 2684778.

- ^ Tuerk C, Gold L (August 1990). "Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase". Science. 249 (4968): 505–510. Bibcode:1990Sci...249..505T. doi:10.1126/science.2200121. PMID 2200121.

- ^ Stoltenburg R, Reinemann C, Strehlitz B (October 2007). "SELEX--a (r)evolutionary method to generate high-affinity nucleic acid ligands". Biomolecular Engineering. 24 (4): 381–403. doi:10.1016/j.bioeng.2007.06.001. PMID 17627883.

- ^ Ellington AD, Szostak JW (February 1992). "Selection in vitro of single-stranded DNA molecules that fold into specific ligand-binding structures". Nature. 355 (6363): 850–852. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..850E. doi:10.1038/355850a0. PMID 1538766. S2CID 4332485.

- ^ Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ (February 1992). "Selection of single-stranded DNA molecules that bind and inhibit human thrombin". Nature. 355 (6360): 564–566. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..564B. doi:10.1038/355564a0. PMID 1741036. S2CID 4349607.

- ^ Cox JC, Ellington AD (October 2001). "Automated selection of anti-protein aptamers". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (10): 2525–2531. doi:10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00028-1. PMID 11557339.

- ^ Cox JC, Rajendran M, Riedel T, Davidson EA, Sooter LJ, Bayer TS, et al. (June 2002). "Automated acquisition of aptamer sequences". Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening. 5 (4): 289–299. doi:10.2174/1386207023330291. PMID 12052180.

- ^ Cox JC, Hayhurst A, Hesselberth J, Bayer TS, Georgiou G, Ellington AD (October 2002). "Automated selection of aptamers against protein targets translated in vitro: from gene to aptamer". Nucleic Acids Research. 30 (20): 108e–108. doi:10.1093/nar/gnf107. PMC 137152. PMID 12384610.

- ^ Breaker RR (February 2012). "Riboswitches and the RNA world". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 4 (2) a003566. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003566. PMC 3281570. PMID 21106649.

- ^ Svigelj R, Dossi N, Toniolo R, Miranda-Castro R, de-Los-Santos-Álvarez N, Lobo-Castañón MJ (September 2018). "Selection of Anti-gluten DNA Aptamers in a Deep Eutectic Solvent". Angewandte Chemie. 57 (39): 12850–12854. Bibcode:2018AngCh.13013032S. doi:10.1002/ange.201804860. hdl:10651/49996. PMID 30070419. S2CID 240281828.

- ^ Neves MA, Reinstein O, Saad M, Johnson PE (December 2010). "Defining the secondary structural requirements of a cocaine-binding aptamer by a thermodynamic and mutation study". Biophysical Chemistry. 153 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.bpc.2010.09.009. PMID 21035241.

- ^ Baugh C, Grate D, Wilson C (August 2000). "2.8 A crystal structure of the malachite green aptamer". Journal of Molecular Biology. 301 (1): 117–128. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3951. PMID 10926496.

- ^ Dieckmann T, Fujikawa E, Xhao X, Szostak J, Feigon J (1995). "Structural Investigations of RNA and DNA aptamers in Solution". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 59: 13–81. doi:10.1002/jcb.240590703. S2CID 221833821.

- ^ Mascini M, Palchetti I, Tombelli S (February 2012). "Nucleic acid and peptide aptamers: fundamentals and bioanalytical aspects". Angewandte Chemie. 51 (6): 1316–1332. Bibcode:2012ACIE...51.1316M. doi:10.1002/anie.201006630. PMID 22213382.

- ^ Lipi F, Chen S, Chakravarthy M, Rakesh S, Veedu RN (December 2016). "In vitro evolution of chemically-modified nucleic acid aptamers: Pros and cons, and comprehensive selection strategies". RNA Biology. 13 (12): 1232–1245. doi:10.1080/15476286.2016.1236173. PMC 5207382. PMID 27715478.

- ^ Chen A, Yan M, Yang S (2016). "Split aptamers and their applications in sandwich aptasensors". TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 80: 581–593. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2016.04.006.

- ^ Kent AD, Spiropulos NG, Heemstra JM (October 2013). "General approach for engineering small-molecule-binding DNA split aptamers". Analytical Chemistry. 85 (20): 9916–9923. doi:10.1021/ac402500n. PMID 24033257.

- ^ Debiais M, Lelievre A, Smietana M, Müller S (April 2020). "Splitting aptamers and nucleic acid enzymes for the development of advanced biosensors". Nucleic Acids Research. 48 (7): 3400–3422. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa132. PMC 7144939. PMID 32112111.

- ^ Drolet DW, Green LS, Gold L, Janjic N (June 2016). "Fit for the Eye: Aptamers in Ocular Disorders". Nucleic Acid Therapeutics. 26 (3): 127–146. doi:10.1089/nat.2015.0573. PMC 4900223. PMID 26757406.

- ^ Wang AZ, Farokhzad OC (March 2014). "Current progress of aptamer-based molecular imaging". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 55 (3): 353–356. doi:10.2967/jnumed.113.126144. PMC 4110511. PMID 24525205.

- ^ Banerjee, S.; Hemmat, M.A.; Shubham, S.; Gosai, A.; Devarakonda, S.; Jiang, N.; Geekiyanage, C.; Dillard, J.A.; Maury, W.; Shrotriya, P.; et al. Structurally Different Yet Functionally Similar: Aptamers Specific for the Ebola Virus Soluble Glycoprotein and GP1,2 and Their Application in Electrochemical Sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054627

- ^ a b Kaur H, Shorie M (June 2019). "Nanomaterial based aptasensors for clinical and environmental diagnostic applications". Nanoscale Advances. 1 (6): 2123–2138. Bibcode:2019NanoA...1.2123K. doi:10.1039/C9NA00153K. PMC 9418768. PMID 36131986.

- ^ Mallikaratchy P (January 2017). "Evolution of Complex Target SELEX to Identify Aptamers against Mammalian Cell-Surface Antigens". Molecules. 22 (2): 215. doi:10.3390/molecules22020215. PMC 5572134. PMID 28146093.

- ^ Potty AS, Kourentzi K, Fang H, Jackson GW, Zhang X, Legge GB, Willson RC (February 2009). "Biophysical characterization of DNA aptamer interactions with vascular endothelial growth factor". Biopolymers. 91 (2): 145–156. doi:10.1002/bip.21097. PMID 19025993. S2CID 23670.

- ^ Long SB, Long MB, White RR, Sullenger BA (December 2008). "Crystal structure of an RNA aptamer bound to thrombin". RNA. 14 (12): 2504–2512. doi:10.1261/rna.1239308. PMC 2590953. PMID 18971322.

- ^ Kohn, Eric M.; Konovalov, Kirill; Gomez, Christian A.; Hoover, Gillian N.; Yik, Andrew Kai-hei; Huang, Xuhui; Martell, Jeffrey D. (2023-08-02). "Terminal Alkyne-Modified DNA Aptamers with Enhanced Protein Binding Affinities". ACS Chemical Biology. 18 (9): 1976–1984. doi:10.1021/acschembio.3c00183. ISSN 1554-8929. PMID 37531184.

- ^ Darfeuille F, Reigadas S, Hansen JB, Orum H, Di Primo C, Toulmé JJ (October 2006). "Aptamers targeted to an RNA hairpin show improved specificity compared to that of complementary oligonucleotides". Biochemistry. 45 (39): 12076–12082. doi:10.1021/bi0606344. PMID 17002307.

- ^ Liu M, Kagahara T, Abe H, Ito Y (2009). "Direct In Vitro Selection of Hemin-Binding DNA Aptamer with Peroxidase Activity". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 82: 99–104. doi:10.1246/bcsj.82.99.

- ^ Min K, Cho M, Han SY, Shim YB, Ku J, Ban C (July 2008). "A simple and direct electrochemical detection of interferon-gamma using its RNA and DNA aptamers". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 23 (12): 1819–1824. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2008.02.021. PMID 18406597.

- ^ Ng EW, Shima DT, Calias P, Cunningham ET, Guyer DR, Adamis AP (February 2006). "Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 5 (2): 123–132. doi:10.1038/nrd1955. PMID 16518379. S2CID 8833436.

- ^ Moghadam, Fatemeh Mortazavi; Rahaie, Mahdi (May 2019). "A signal-on nanobiosensor for VEGF165 detection based on supraparticle copper nanoclusters formed on bivalent aptamer". Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 132: 186–195. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2019.02.046. PMID 30875630. S2CID 80613434.

- ^ Savory N, Abe K, Sode K, Ikebukuro K (December 2010). "Selection of DNA aptamer against prostate specific antigen using a genetic algorithm and application to sensing". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 26 (4): 1386–1391. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2010.07.057. PMID 20692149.

- ^ Jeong S, Han SR, Lee YJ, Lee SW (March 2010). "Selection of RNA aptamers specific to active prostate-specific antigen". Biotechnology Letters. 32 (3): 379–385. doi:10.1007/s10529-009-0168-1. PMID 19943183. S2CID 22201181.

- ^ Walsh R, DeRosa MC (October 2009). "Retention of function in the DNA homolog of the RNA dopamine aptamer". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 388 (4): 732–735. Bibcode:2009BBRC..388..732W. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.084. PMID 19699181.

- ^ Salamanca HH, Antonyak MA, Cerione RA, Shi H, Lis JT (2014). "Inhibiting heat shock factor 1 in human cancer cells with a potent RNA aptamer". PLOS ONE. 9 (5) e96330. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...996330S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096330. PMC 4011729. PMID 24800749.

- ^ Farokhzad OC, Karp JM, Langer R (May 2006). "Nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer targeting". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 3 (3): 311–324. doi:10.1517/17425247.3.3.311. PMID 16640493. S2CID 37058942.

- ^ Proske D, Gilch S, Wopfner F, Schätzl HM, Winnacker EL, Famulok M (August 2002). "Prion-protein-specific aptamer reduces PrPSc formation". ChemBioChem. 3 (8): 717–725. doi:10.1002/1439-7633(20020802)3:8<717::AID-CBIC717>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 12203970. S2CID 36801266.

- ^ Kaur H, Shorie M, Sharma M, Ganguli AK, Sabherwal P (December 2017). "Bridged Rebar Graphene functionalized aptasensor for pathogenic E. coli O78:K80:H11 detection". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 98: 486–493. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2017.07.004. PMID 28728009.

- ^ a b c Asha K, Kumar P, Sanicas M, Meseko CA, Khanna M, Kumar B (December 2018). "Advancements in Nucleic Acid Based Therapeutics against Respiratory Viral Infections". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 8 (1): 6. doi:10.3390/jcm8010006. PMC 6351902. PMID 30577479.

- ^ Schmitz A, Weber A, Bayin M, Breuers S, Fieberg V, Famulok M, Mayer G (April 2021). "A SARS-CoV-2 Spike Binding DNA Aptamer that Inhibits Pseudovirus Infection by an RBD-Independent Mechanism*". Angewandte Chemie. 60 (18): 10279–10285. doi:10.1002/anie.202100316. PMC 8251191. PMID 33683787.

- ^ Dhar P, Samarasinghe RM, Shigdar S (April 2020). "Antibodies, Nanobodies, or Aptamers-Which Is Best for Deciphering the Proteomes of Non-Model Species?". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (7): 2485. doi:10.3390/ijms21072485. PMC 7177290. PMID 32260091.

- ^ a b Bauer M, Strom M, Hammond DS, Shigdar S (November 2019). "Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better: Can Aptamers Replace Antibodies in Clinical Diagnostic Applications?". Molecules. 24 (23): 4377. doi:10.3390/molecules24234377. PMC 6930532. PMID 31801185.

- ^ Feng S, Chen C, Wang W, Que L (May 2018). "An aptamer nanopore-enabled microsensor for detection of theophylline". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 105: 36–41. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2018.01.016. PMID 29351868.

- ^ Song C (2017). "Detection of plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) using an optical aptamer-based sensor with a microfluidics capillary interface". 2017 IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS). pp. 370–373. doi:10.1109/MEMSYS.2017.7863418. ISBN 978-1-5090-5078-9. S2CID 20781208.

- ^ Muszyńska K, Ostrowska D, Bartnicki F, Kowalska E, Bodaszewska-Lubaś M, Hermanowicz P, et al. (2017). "Selection and analysis of a DNA aptamer binding α-amanitin from Amanita phalloides". Acta Biochimica Polonica. 64 (3): 401–406. doi:10.18388/abp.2017_1615. PMID 28787470. S2CID 3638299.

- ^ Penner G (July 2012). "Commercialization of an aptamer-based diagnostic test" (PDF). NeoVentures.

- ^ Wei H, Li B, Li J, Wang E, Dong S (September 2007). "Simple and sensitive aptamer-based colorimetric sensing of protein using unmodified gold nanoparticle probes". Chemical Communications (36): 3735–3737. doi:10.1039/B707642H. PMID 17851611.

- ^ Cheng H, Qiu X, Zhao X, Meng W, Huo D, Wei H (March 2016). "Functional Nucleic Acid Probe for Parallel Monitoring K(+) and Protoporphyrin IX in Living Organisms". Analytical Chemistry. 88 (5): 2937–2943. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04936. PMID 26866998.

- ^ Xiang Y, Lu Y (July 2011). "Using personal glucose meters and functional DNA sensors to quantify a variety of analytical targets". Nature Chemistry. 3 (9): 697–703. Bibcode:2011NatCh...3..697X. doi:10.1038/nchem.1092. PMC 3299819. PMID 21860458.

- ^ Agnivo Gosai, Brendan Shin Hau Yeah, Marit Nilsen-Hamilton, Pranav Shrotriya, "Label free thrombin detection in presence of high concentration of albumin using an aptamer-functionalized nanoporous membrane", Biosensors and Bioelectronics, Volume 126, 2019, pp. 88–95, ISSN 0956-5663, doi:10.1016/j.bios.2018.10.010.

- ^ Amero P, Khatua S, Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Lopez-Berestein G (October 2020). "Aptamers: Novel Therapeutics and Potential Role in Neuro-Oncology". Cancers. 12 (10): 2889. doi:10.3390/cancers12102889. PMC 7600320. PMID 33050158.

- ^ Fattal E, Hillaireau H, Ismail SI (September 2018). "Aptamers in Therapeutics and Drug Delivery". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 134: 1–2. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2018.11.001. PMID 30442313. S2CID 53562925.

- ^ Hafner M, Vianini E, Albertoni B, Marchetti L, Grüne I, Gloeckner C, Famulok M (2008). "Displacement of protein-bound aptamers with small molecules screened by fluorescence polarization". Nature Protocols. 3 (4): 579–587. doi:10.1038/nprot.2008.15. PMID 18388939. S2CID 4997899.

- ^ Huang Z, Qiu L, Zhang T, Tan W (2021-02-03). "Integrating DNA Nanotechnology with Aptamers for Biological and Biomedical Applications". Matter. 4 (2): 461–489. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2020.11.002. ISSN 2590-2385. S2CID 234061584.

- ^ Reynaud L, Bouchet-Spinelli A, Raillon C, Buhot A (August 2020). "Sensing with Nanopores and Aptamers: A Way Forward". Sensors. 20 (16): 4495. Bibcode:2020Senso..20.4495R. doi:10.3390/s20164495. PMC 7472324. PMID 32796729.

- ^ Yang Y, Yin S, Li Y, Lu D, Zhang J, Sun C (2017). "Application of aptamers in detection and chromatographic purification of antibiotics in different matrices". TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 95: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2017.07.023. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Murphy MB, Fuller ST, Richardson PM, Doyle SA (September 2003). "An improved method for the in vitro evolution of aptamers and applications in protein detection and purification". Nucleic Acids Research. 31 (18): 110e–110. doi:10.1093/nar/gng110. PMC 203336. PMID 12954786.

- ^ Chen K, Zhou J, Shao Z, Liu J, Song J, Wang R, et al. (July 2020). "Aptamers as Versatile Molecular Tools for Antibody Production Monitoring and Quality Control". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 142 (28): 12079–12086. Bibcode:2020JAChS.14212079C. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b13370. PMID 32516525. S2CID 219564070.

- ^ Keijzer JF, Albada B (March 2022). "DNA-assisted site-selective protein modification". Biopolymers. 113 (3) e23483. doi:10.1002/bip.23483. PMC 9285461. PMID 34878181. S2CID 244954278.

- ^ Smith D, Collins BD, Heil J, Koch TH (January 2003). "Sensitivity and specificity of photoaptamer probes". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1074/mcp.m200059-mcp200. PMID 12601078. S2CID 13406870.

- ^ Vinkenborg JL, Mayer G, Famulok M (September 2012). "Aptamer-based affinity labeling of proteins". Angewandte Chemie. 51 (36): 9176–9180. Bibcode:2012ACIE...51.9176V. doi:10.1002/anie.201204174. PMID 22865679.

- ^ Keijzer JF, Firet J, Albada B (December 2021). "Site-selective and inducible acylation of thrombin using aptamer-catalyst conjugates". Chemical Communications. 57 (96): 12960–12963. doi:10.1039/d1cc05446e. PMID 34792071. S2CID 243998479.

- ^ Wilson, Brandon D.; Soh, H. Tom (2020-08-01). "Re-Evaluating the Conventional Wisdom about Binding Assays". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 45 (8): 639–649. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2020.04.005. ISSN 0968-0004. PMC 7368832. PMID 32402748.

- ^ Janson, Jan-Christer (2012-01-03). Protein Purification: Principles, High Resolution Methods, and Applications. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-00219-3.

- ^ Chen A, Yang S (September 2015). "Replacing antibodies with aptamers in lateral flow immunoassay". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 71: 230–242. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2015.04.041. PMID 25912679.

- ^ Toh SY, Citartan M, Gopinath SC, Tang TH (February 2015). "Aptamers as a replacement for antibodies in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay". Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 64: 392–403. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2014.09.026. PMID 25278480.

- ^ Bruno JG, Sivils JC (2016). "Aptamer "Western" blotting for E. coli outer membrane proteins and key virulence factors in pathogenic E. coli serotypes". Aptamers and Synthetic Antibodies.[dead link]

- ^ Bauer M, Macdonald J, Henri J, Duan W, Shigdar S (June 2016). "The Application of Aptamers for Immunohistochemistry". Nucleic Acid Therapeutics. 26 (3): 120–126. doi:10.1089/nat.2015.0569. PMID 26862683.

- ^ Meyer M, Scheper T, Walter JG (August 2013). "Aptamers: versatile probes for flow cytometry". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 97 (16): 7097–7109. doi:10.1007/s00253-013-5070-z. PMID 23838792. S2CID 13996688.

- ^ Zhou J, Rossi J (March 2017). "Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: current potential and challenges". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 16 (3): 181–202. doi:10.1038/nrd.2016.199. PMC 5700751. PMID 27807347.

- ^ Bruno JG (April 2015). "Predicting the Uncertain Future of Aptamer-Based Diagnostics and Therapeutics". Molecules. 20 (4): 6866–6887. doi:10.3390/molecules20046866. PMC 6272696. PMID 25913927.

- ^ Wang T, Chen C, Larcher LM, Barrero RA, Veedu RN (2019). "Three decades of nucleic acid aptamer technologies: Lessons learned, progress and opportunities on aptamer development". Biotechnology Advances. 37 (1): 28–50. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.001. PMID 30408510. S2CID 53242220.

- ^ Melbourne J, Bishop P, Brown J, Stoddart G (October 2016). "A multi-faceted approach to achieving the global acceptance of animal-free research methods". Alternatives to Laboratory Animals. 44 (5): 495–498. doi:10.1177/026119291604400511. PMID 27805832. S2CID 1002312.

- ^ Alfaleh MA, Alsaab HO, Mahmoud AB, Alkayyal AA, Jones ML, Mahler SM, Hashem AM (2020). "Phage Display Derived Monoclonal Antibodies: From Bench to Bedside". Frontiers in Immunology. 11 1986. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01986. PMC 7485114. PMID 32983137.

- ^ Soontornworajit B, Zhou J, Shaw MT, Fan TH, Wang Y (March 2010). "Hydrogel functionalization with DNA aptamers for sustained PDGF-BB release". Chemical Communications. 46 (11): 1857–1859. doi:10.1039/B924909E. PMID 20198232.

- ^ Battig MR, Soontornworajit B, Wang Y (August 2012). "Programmable release of multiple protein drugs from aptamer-functionalized hydrogels via nucleic acid hybridization". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 134 (30): 12410–12413. Bibcode:2012JAChS.13412410B. doi:10.1021/ja305238a. PMID 22816442.

- ^ Stejskalová A, Oliva N, England FJ, Almquist BD (February 2019). "Biologically Inspired, Cell-Selective Release of Aptamer-Trapped Growth Factors by Traction Forces". Advanced Materials. 31 (7) e1806380. Bibcode:2019AdM....3106380S. doi:10.1002/adma.201806380. PMC 6375388. PMID 30614086.

- ^ Rana D, Rangel VR, Padmanaban P, Trikalitis VD, Kandar A, Kim HW, Rouwkema J (2024-11-01). "Bioprinting of Aptamer-Based Programmable Bioinks to Modulate Multiscale Microvascular Morphogenesis in 4D". Advanced Healthcare Materials. 14 (1) 2402302. doi:10.1002/adhm.202402302. PMC 11694088. PMID 39487611.

- ^ Rana D, Kandar A, Salehi-Nik N, Inci I, Koopman B, Rouwkema J (2021-10-23). "Spatiotemporally controlled, aptamers-mediated growth factor release locally manipulates microvasculature formation within engineered tissues". Bioactive Materials. 12: 71–84. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.10.024. PMC 8777207. PMID 35087964.

- ^ Berezovski MV, Lechmann M, Musheev MU, Mak TW, Krylov SN (July 2008). "Aptamer-facilitated biomarker discovery (AptaBiD)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (28): 9137–9143. Bibcode:2008JAChS.130.9137B. doi:10.1021/ja801951p. PMID 18558676.

- ^ Colas P, Cohen B, Jessen T, Grishina I, McCoy J, Brent R (April 1996). "Genetic selection of peptide aptamers that recognize and inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase 2". Nature. 380 (6574): 548–550. Bibcode:1996Natur.380..548C. doi:10.1038/380548a0. PMID 8606778. S2CID 4327303.

- ^ Nolan GP (January 2005). "Tadpoles by the tail". Nature Methods. 2 (1): 11–12. doi:10.1038/nmeth0105-11. PMID 15782163. S2CID 1423778.

- ^ Spolar RS, Record MT (February 1994). "Coupling of local folding to site-specific binding of proteins to DNA". Science. 263 (5148): 777–784. Bibcode:1994Sci...263..777S. doi:10.1126/science.8303294. PMID 8303294.

- ^ Huang J, Ru B, Zhu P, Nie F, Yang J, Wang X, et al. (January 2012). "MimoDB 2.0: a mimotope database and beyond". Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (Database issue): D271–D277. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr922. PMC 3245166. PMID 22053087.

- ^ "MimoDB: a mimotope database and beyond". immunet.cn. Archived from the original on 2012-11-16. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ^ Geyer CR, Colman-Lerner A, Brent R (July 1999). ""Mutagenesis" by peptide aptamers identifies genetic network members and pathway connections". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (15): 8567–8572. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.8567G. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.15.8567. PMC 17557. PMID 10411916.

- ^ Dibenedetto S, Cluet D, Stebe PN, Baumle V, Léault J, Terreux R, et al. (July 2013). "Calcineurin A versus NS5A-TP2/HD domain containing 2: a case study of site-directed low-frequency random mutagenesis for dissecting target specificity of peptide aptamers". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 12 (7): 1939–1952. doi:10.1074/mcp.M112.024612. PMC 3708177. PMID 23579184.

- ^ Colas P, Cohen B, Ko Ferrigno P, Silver PA, Brent R (December 2000). "Targeted modification and transportation of cellular proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (25): 13720–13725. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9713720C. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.25.13720. PMC 17642. PMID 11106396.

- ^ "FDA Approves Eyetech/Pfizer's Macugen". Review of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Dutt S. "SomaLogic and Illumina Combine Strengths to Propel Innovation in Proteomics". BioSpace. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "Apta-Index™ (Aptamer Database) - Library of 500+ Aptamers". APTAGEN, LLC. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

Further reading

[edit]- Ellington AD, Szostak JW (August 1990). "In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands". Nature. 346 (6287): 818–822. Bibcode:1990Natur.346..818E. doi:10.1038/346818a0. PMID 1697402. S2CID 4273647.

- Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ (February 1992). "Selection of single-stranded DNA molecules that bind and inhibit human thrombin". Nature. 355 (6360): 564–566. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..564B. doi:10.1038/355564a0. PMID 1741036. S2CID 4349607.

- Hoppe-Seyler F, Butz K (2000). "Peptide aptamers: powerful new tools for molecular medicine". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 78 (8): 426–430. doi:10.1007/s001090000140. PMID 11097111. S2CID 52872561.

- Carothers JM, Oestreich SC, Davis JH, Szostak JW (April 2004). "Informational complexity and functional activity of RNA structures". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 126 (16): 5130–5137. Bibcode:2004JAChS.126.5130C. doi:10.1021/ja031504a. PMC 5042360. PMID 15099096.

- Cohen BA, Colas P, Brent R (November 1998). "An artificial cell-cycle inhibitor isolated from a combinatorial library". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (24): 14272–14277. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9514272C. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.24.14272. PMC 24363. PMID 9826690.

- Binkowski BF, Miller RA, Belshaw PJ (July 2005). "Ligand-regulated peptides: a general approach for modulating protein-peptide interactions with small molecules". Chemistry & Biology. 12 (7): 847–855. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.021. PMID 16039531.

- Sullenger BA, Gilboa E (July 2002). "Emerging clinical applications of RNA". Nature. 418 (6894): 252–258. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..252S. doi:10.1038/418252a. PMID 12110902. S2CID 4431755.

- Ng EW, Shima DT, Calias P, Cunningham ET, Guyer DR, Adamis AP (February 2006). "Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 5 (2): 123–132. doi:10.1038/nrd1955. PMID 16518379. S2CID 8833436.

- Drabovich AP, Berezovski M, Okhonin V, Krylov SN (May 2006). "Selection of smart aptamers by methods of kinetic capillary electrophoresis". Analytical Chemistry. 78 (9): 3171–3178. doi:10.1021/ac060144h. PMID 16643010.

- Cho EJ, Lee JW, Ellington, ADCho EJ, Lee JW, Ellington AD (2009). "Applications of aptamers as sensors". Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry. 2 (1): 241–264. Bibcode:2009ARAC....2..241C. doi:10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112851. PMID 20636061.

- Spill F, Weinstein ZB, Irani Shemirani A, Ho N, Desai D, Zaman MH (October 2016). "Controlling uncertainty in aptamer selection". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (43): 12076–12081. arXiv:1612.08995. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11312076S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1605086113. PMC 5087011. PMID 27790993.

Aptamer

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Etymology

The term "aptamer" was coined in 1990 by Andrew D. Ellington and Jack W. Szostak during their pioneering work on the in vitro selection of RNA molecules capable of binding specific ligands with high affinity.[14] This neologism emerged as part of the foundational discovery process, where the researchers sought a descriptor for short, structured nucleic acid sequences that function as targeted binding agents, distinct from naturally occurring biomolecules like antibodies. Etymologically, "aptamer" derives from the Latin word aptus, meaning "to fit," combined with the Greek meros, meaning "part" or "region," emphasizing the molecules' ability to form precise, complementary interactions with target structures, much like a custom-fitted component. In their original publication, Ellington and Szostak explicitly defined the term in this manner to highlight the selective "fit" achieved through evolutionary in vitro processes.Definition and Characteristics

Aptamers are short, single-stranded oligonucleotides or peptides that fold into specific three-dimensional structures to bind target molecules with high affinity and specificity, often comparable to that of antibodies. Nucleic acid aptamers, the most common type, typically consist of 20-80 nucleotides of DNA or RNA, while peptide aptamers are constrained peptides of 5-20 amino acids usually displayed on a stable protein scaffold such as thioredoxin. These molecules recognize a wide range of targets, including proteins, small molecules, and cells, through non-covalent interactions that enable precise molecular recognition.[1][15][16] A defining characteristic of aptamers is their binding affinity, with dissociation constants (Kd) typically in the nanomolar to picomolar range, allowing for strong yet tunable interactions. Their small molecular weight—generally 6-30 kDa for nucleic acid aptamers—facilitates rapid tissue penetration and straightforward chemical synthesis, which supports scalable production and modifications such as pegylation for enhanced stability. Unlike antibodies, aptamers exhibit low immunogenicity due to their synthetic nature and lack of immune-triggering epitopes, making them suitable for in vivo applications. Additionally, their binding is reversible and often conformation-dependent, permitting controlled release or antidote-mediated neutralization in therapeutic contexts.[17][4][18] Aptamers are frequently referred to as "chemical antibodies" because they serve as versatile molecular recognition elements in diagnostics, therapeutics, and biosensors, offering advantages in stability and ease of engineering over traditional biologics.[19]History

Discovery

The discovery of aptamers stemmed from two independent breakthroughs in 1990 that demonstrated the potential of in vitro selection to evolve nucleic acid molecules capable of specific ligand binding. At the University of Colorado, Craig Tuerk and Larry Gold initiated the process by starting with a known RNA hairpin from bacteriophage T4 gene 43 mRNA, which binds to the T4 DNA polymerase, and systematically mutated an 8-nucleotide loop to explore binding variants. Through iterative cycles of binding, partitioning, and amplification from a library of variants, they enriched for high-affinity RNA sequences that inhibited the polymerase, marking the first use of a combinatorial approach to evolve functional nucleic acids from a diverse pool. This method, termed Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX), represented a pioneering demonstration of in vitro selection from random-sequence libraries to generate ligand-binding RNAs.[20] Concurrently, at Harvard University, Andrew D. Ellington and Jack W. Szostak developed a parallel strategy to isolate RNA molecules that bind small organic dyes, such as Cibacron Blue 3GA, from a large pool of approximately 10^14 random-sequence RNAs. They employed cycles of affinity chromatography to partition bound RNAs, followed by reverse transcription, PCR amplification, and in vitro transcription to generate enriched libraries for subsequent rounds, ultimately yielding RNA subpopulations with specific, high-affinity binding sites for the dyes. This work independently showcased the feasibility of selecting functional RNA structures from vast random libraries, highlighting the versatility of RNA as a ligand scaffold akin to antibodies.[14] These foundational experiments, published in rapid succession—Tuerk and Gold in Science on August 3, 1990, and Ellington and Szostak in Nature on August 30, 1990—established the core principles of aptamer generation through SELEX, without which later refinements would not have been possible. The term "aptamer," derived from the Latin "aptus" meaning "to fit," was coined by Ellington and Szostak to describe these selected nucleic acid ligands.[14][5]Key Developments

Following the initial discovery of aptamers in 1990, the 1990s saw significant refinements to the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX) process, including optimizations for efficiency and specificity that enabled the generation of aptamers against a broader range of targets.[21][15] These advancements culminated in the approval of the first therapeutic aptamer, pegaptanib sodium (Macugen), by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on December 17, 2004, for the treatment of neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration.[22] Pegaptanib targets vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), demonstrating aptamers' potential as targeted inhibitors in clinical settings.[23] In the 2000s and 2010s, efforts focused on enhancing aptamer stability to overcome nuclease degradation, leading to the widespread adoption of chemical modifications such as 2'-fluoro, 2'-O-methyl, and 2'-amino substitutions on the ribose sugar; backbone alterations like phosphorothioate linkages; and mirror-image L-nucleotides (Spiegelmers), which extended serum half-lives from minutes to hours or days.[24][25][26] Concurrently, cell-SELEX emerged as a pivotal innovation around 2004, allowing the selection of aptamers against intact cells or complex surface markers without prior knowledge of specific targets, facilitating applications in cancer cell targeting and diagnostics.[27] For peptide aptamers, initial selections using yeast surface display were reported in the late 1990s and early 2000s, enabling high-throughput screening of constrained peptide libraries for intracellular protein interactions.[28][29] The 2020s marked further clinical progress, with the FDA approving a second aptamer therapeutic, avacincaptad pegol (Izervay), on August 4, 2023, for geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration, highlighting aptamers' expanding role in ophthalmology.[10] This approval coincided with a surge in aptamer-based clinical trials, including olaptesed pegol (NOX-A12), a CXCL12 inhibitor advancing in phase 1/2 studies for oncology indications such as glioblastoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, often in combination with radiotherapy or immunotherapy to modulate the tumor microenvironment.[30][31]Classification

Nucleic Acid Aptamers

Nucleic acid aptamers represent the foundational class of aptamers, consisting of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or RNA (ssRNA) molecules that fold into unique three-dimensional conformations to recognize and bind specific targets with high affinity and specificity, often comparable to antibodies. These oligonucleotides, typically 20 to 80 nucleotides in length, are derived from vast libraries of random sequences during in vitro selection processes. Unlike peptide aptamers, which utilize protein-derived scaffolds, nucleic acid aptamers rely on the inherent flexibility and base-pairing properties of nucleotides for target interaction. DNA aptamers, composed of deoxyribonucleotide units, offer superior chemical and thermal stability due to the absence of the 2'-hydroxyl group found in RNA, and they can readily form double-stranded helical structures under certain conditions. In contrast, RNA aptamers incorporate ribonucleotides, enabling more intricate three-dimensional folds through additional hydrogen bonding and steric interactions, which often result in greater structural diversity and adaptability for binding complex targets. Xenonucleic acid (XNA) aptamers extend this category by employing synthetic analogs with alternative sugar moieties, such as threose or arabinose, replacing the natural ribose or deoxyribose; these variants exhibit markedly enhanced resistance to nuclease degradation while maintaining functional binding capabilities. To further bolster stability in biological environments, nucleic acid aptamers frequently undergo chemical modifications, including substitutions at the 2'-position of the sugar (e.g., 2'-fluoro or 2'-O-methyl groups) or incorporation of locked nucleic acids (LNAs), which reduce susceptibility to endonucleases and exonucleases without compromising target affinity. These modifications are particularly crucial for therapeutic applications, as unmodified aptamers can degrade rapidly in serum. Libraries for aptamer selection generally comprise 10^14 to 10^15 unique random sequences flanked by primer-binding regions, allowing for the isolation of high-affinity binders through iterative enrichment. A prominent example of a nucleic acid aptamer is NU172, a 26-nucleotide DNA aptamer designed to bind exosite I of human thrombin, potently inhibiting its fibrin-clotting activity with a dissociation constant in the nanomolar range; it progressed to Phase II clinical trials as an anticoagulant for cardiac surgery patients.Peptide Aptamers

Peptide aptamers are combinatorial protein reagents consisting of a short, variable peptide sequence, typically 10-20 amino acids long, inserted into a stable scaffold protein to constrain its conformation and enable specific binding to target molecules.[32][3] This design mimics antibody-antigen interactions but allows intracellular expression, making them suitable for modulating protein function within cells.[33] The scaffold provides structural rigidity, ensuring the peptide loop adopts a defined three-dimensional shape for high-affinity, sequence-specific recognition of target proteins.[34] Unlike the more common nucleic acid aptamers, peptide aptamers are protein-based and selected through genetic libraries rather than in vitro chemical evolution.[35] Subtypes of peptide aptamers are primarily distinguished by the choice of scaffold protein, which influences stability, solubility, and binding efficiency. The most widely used scaffold is thioredoxin A (TrxA) from Escherichia coli, where the variable peptide is displayed in the active-site loop to maintain a constrained loop structure.[32][34] Alternative scaffolds include bacterial proteins like those from other prokaryotes or engineered variants, as well as scaffolds from eukaryotic sources such as Plasmodium falciparum thioredoxin (PfTrx), which offers enhanced immunogenicity for vaccine applications.[36] Peptide aptamers can also be categorized by their display systems during selection, such as the yeast two-hybrid system, which facilitates intracellular screening for protein-protein interactions, or bacterial surface display for high-throughput identification.[37][3] A prominent example is the E7-binding peptide aptamer developed for human papillomavirus (HPV) research, where aptamers targeting the E7 oncoprotein were selected using a thioredoxin scaffold to inhibit its activity and induce apoptosis in HPV-positive cervical carcinoma cells.[38] This aptamer, isolated through yeast two-hybrid screening, demonstrated high specificity for E7, disrupting its interaction with cellular targets like retinoblastoma protein and providing a model for antiviral therapeutics.[39] Seminal work also includes early peptide aptamers against cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), which were the first to be genetically selected and shown to block cell cycle progression by mimicking natural inhibitors.[32] These examples highlight peptide aptamers' utility in dissecting protein networks and validating drug targets.Structure and Properties

Nucleic Acid Aptamer Structure

Nucleic acid aptamers are short, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or RNA (ssRNA) oligonucleotides, typically ranging from 25 to 80 nucleotides in length, consisting of a central randomized sequence flanked by fixed primer regions for amplification during selection.[40] This primary structure provides the sequence diversity essential for evolving specific binding conformations, with the linear chain serving as the scaffold for higher-order folding. At the secondary structure level, aptamers fold through intramolecular base pairing to form motifs such as stem-loops (hairpins), pseudoknots, bulges, and internal loops, which contribute to structural rigidity and specificity.[40] G-quadruplexes, formed in guanine-rich sequences by stacking of G-tetrads stabilized by monovalent cations like potassium, represent another key motif; for instance, the thrombin-binding aptamer (TBA), a 15-nucleotide ssDNA sequence (d(GGTTGGTGTGGTTGG)), adopts an intramolecular antiparallel G-quadruplex with two G-tetrads and a TGT loop, enabling high-affinity target recognition.[41] Pseudoknots, involving crossing of base-paired stems, occur in certain aptamers to create compact architectures that enhance binding pockets, as seen in some RNA aptamers targeting viral proteins.[40] These secondary elements transition to tertiary structures via additional base stacking, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions, resulting in well-defined three-dimensional conformations that mimic protein active sites for target interaction. To enhance biostability against nuclease degradation and improve pharmacokinetics, aptamers are often chemically modified using diverse strategies that preserve their ability to fold into specific binding conformations while conferring resistance to nucleases. Common approaches include sugar moiety substitutions such as 2'-fluoro (2'-F), 2'-O-methyl (2'-OMe), and 2'-amino (2'-NH₂) groups, which protect against enzymatic cleavage and can stabilize secondary structures; backbone modifications such as phosphorothioate or phosphorodithioate linkages; incorporation of unnatural base pairs; mirror-image L-nucleic acids (Spiegelmers using L-DNA or L-RNA); and protective coatings or conjugations (e.g., PEGylation, oligolysine, or block copolymers). These modifications enhance biostability for applications in biosensing, drug delivery, and therapeutics while preserving specific binding capabilities.[42][18] For instance, incorporation of 2'-O-methyl groups on the ribose sugar replaces the 2'-OH with a methoxy group to confer resistance while preserving folding.[24] These modifications increase the melting temperature (Tm) of secondary structures—for example, 2'-O-methyl substitutions in RNA aptamers can raise Tm by approximately 1°C per modified position in model duplexes, stabilizing stem-loops without disrupting overall tertiary architecture.[43] PEGylation, involving conjugation of polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to the 5' or 3' terminus, further extends serum half-life by reducing renal clearance, though it minimally affects intrinsic folding but can influence accessibility of binding sites.[44] Mirror-image L-nucleic acid aptamers (Spiegelmers) exhibit exceptional nuclease resistance due to their non-natural chirality while retaining high-affinity and specific target recognition.[45] Other modifications like phosphorothioate linkages in the backbone also bolster stability while maintaining the aptamer's adaptive folding capability.[40]Peptide Aptamer Structure

Peptide aptamers feature a core design consisting of a short variable peptide loop, typically 5 to 20 amino acids in length, inserted into a stable protein scaffold that constrains its conformation for target binding. The prototypical scaffold is thioredoxin A (TrxA) from Escherichia coli, where the variable sequence replaces the enzyme's active-site loop between two conserved cysteine residues (positions 32 and 35), resulting in a constrained loop of 12 to 20 residues that is presented in a fixed three-dimensional orientation.[32] This insertion disrupts the thioredoxin's redox activity but preserves its overall fold, allowing the scaffold to solubilize and stabilize the peptide without interfering with its binding function.[46] The scaffold imparts conformational stability to the variable loop by enforcing a specific spatial arrangement, often resembling a beta-hairpin or turn structure, which mimics the rigid presentation of complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) in antibody variable domains. This constrained geometry reduces entropy loss upon target binding, thereby enhancing affinity and specificity compared to unconstrained linear peptides, with dissociation constants in the nanomolar range for optimized aptamers.[33] The thioredoxin scaffold's beta-sheet-rich core and solvent-exposed loop position further contribute to this stability, preventing aggregation and enabling intracellular expression in yeast or bacterial two-hybrid systems for selection.[47] Variations in peptide aptamer design include alternative scaffolds beyond thioredoxin A, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) or glutathione S-transferase (GST), which offer similar loop constraints but may improve expression in eukaryotic systems or add functional tags for detection. Multi-valent designs incorporate multiple variable loops within a single scaffold or tandem fusions of aptamer units to achieve cooperative binding and higher avidity against multimeric targets. Additionally, fusions with other protein domains, such as protein transduction domains (PTDs) for cellular delivery or regulatory modules like FKBP-FRB for ligand-inducible control, expand their utility while maintaining structural integrity.[3]Binding Properties

Aptamers exhibit high binding affinity to their targets, typically characterized by dissociation constants (K_d) in the low nanomolar to high picomolar range, often spanning 10-500 nM for many selected sequences.[48] This affinity arises from non-covalent interactions that enable precise molecular recognition, comparable to that of monoclonal antibodies.[2] The specificity of aptamer binding is primarily driven by shape complementarity between the aptamer's three-dimensional structure and the target molecule, supplemented by hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and van der Waals forces.[2] For nucleic acid aptamers, these interactions often involve non-Watson-Crick base pairing and other tertiary contacts that allow the formation of unique binding pockets beyond traditional double-helix motifs.[49] This combination ensures selective engagement, minimizing off-target effects even among structurally similar molecules. Aptamers can target a diverse array of entities, including small molecules, proteins, whole cells, and viruses, due to their adaptable folding into conformations that accommodate varied target sizes and chemistries.[50] For instance, they bind small molecules like antibiotics or metabolites through pocket-like enclosures, while interacting with proteins via surface epitopes or even enveloping viral particles to block infectivity.[50] Unlike covalent inhibitors that form irreversible bonds, aptamer binding is inherently reversible, governed by association and dissociation kinetics that permit dynamic regulation of target engagement.[51] This reversibility facilitates controlled release or antidote-mediated neutralization, enhancing their utility in tunable therapeutic contexts.[52]Selection and Generation

SELEX for Nucleic Acid Aptamers

The Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX) is an iterative in vitro selection process designed to isolate high-affinity nucleic acid aptamers from large random libraries, independently developed in 1990 by two research groups.[20][14] This method mimics Darwinian evolution by repeatedly enriching sequences with desired binding properties, typically yielding aptamers with dissociation constants in the nanomolar to picomolar range after multiple cycles.[6] The SELEX process commences with the synthesis of a diverse combinatorial library of single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides, comprising 10^{14} to 10^{15} unique sequences to ensure broad coverage of possible structures.[6] Each sequence features a central random region of 20–80 nucleotides flanked by constant primer-binding sites for subsequent amplification. This library is denatured and incubated with the target molecule under controlled conditions to promote specific binding interactions.[53] Partitioning follows incubation, separating bound aptamer-target complexes from unbound sequences to enrich the pool. For immobilized targets—such as proteins attached to magnetic beads, columns, or microtiter plates—unbound aptamers are washed away, while complexes are retained.[6] Alternative methods include nitrocellulose filtration for soluble targets, where protein-nucleic acid complexes are retained on the filter while free aptamers pass through.[20] Bound aptamers are then eluted from the target, commonly by heating to 95°C or altering buffer conditions like pH or ionic strength to disrupt interactions without damaging sequences.[53] The recovered single-stranded nucleic acids are amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to produce double-stranded DNA, which is transcribed to RNA if needed or rendered single-stranded through asymmetric PCR or enzymatic methods, regenerating the enriched library for the next iteration.[6] These cycles of incubation, partitioning, elution, and amplification are repeated for 8–15 rounds, with progressive increases in selection stringency—such as decreasing target concentration, shortening incubation times, or adding competitors—to favor aptamers with higher affinity and specificity.[53] After the final round, sequences are cloned and sequenced to identify individual aptamers for characterization. Variants of SELEX adapt the standard protocol to specific target types or challenges. In Cell-SELEX, whole living cells serve as targets to select aptamers recognizing complex surface epitopes, such as those on cancer cells; the process involves incubating the library with target cells, separating bound aptamers by centrifugation or filtration after washing, eluting by heating, and using non-target cells for counter-selection to discard nonspecific binders.[27] Capture-SELEX addresses limitations with small-molecule targets by immobilizing the oligonucleotide library on a solid support (e.g., streptavidin-coated beads via biotinylated sequences) and passing the soluble target through it, capturing and eluting only target-bound aptamers for amplification; this preserves the target's native conformation and is effective for molecules lacking suitable immobilization sites.[54] Optimization through counter-selection enhances specificity by pre-incubating the aptamer pool with non-target molecules, supports, or control cells to remove sequences with off-target binding, followed by discarding bound material without elution; this step, often integrated after initial rounds or before target exposure, is crucial for reducing cross-reactivity in complex matrices.[53]Selection Methods for Peptide Aptamers

Peptide aptamers are primarily selected using the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system, an in vivo method that enables intracellular screening against target proteins under physiological conditions. This technique, first demonstrated in 1996, involves combinatorial libraries typically comprising 10^6 to 10^9 variants of randomized peptide sequences constrained within a stable scaffold protein, such as thioredoxin A (TrxA), to confer proper folding and solubility. The Y2H system is particularly suited for identifying high-affinity binders to intracellular targets, as it leverages yeast cellular machinery to detect protein-protein interactions. A variant, the yeast three-hybrid system, extends this approach to select aptamers that modulate interactions involving small molecules or RNA, though it is less commonly used for standard peptide aptamer isolation. The selection process begins with library construction, where degenerate oligonucleotides encoding random peptides (usually 8-20 amino acids) are inserted into the scaffold via restriction enzyme sites, followed by cloning into a yeast expression vector fused to a transcriptional activation domain, such as GAL4-AD. These plasmids are then transformed into yeast host cells, achieving high library diversity through efficient mating with bait-expressing strains. The target protein, fused to a DNA-binding domain (e.g., GAL4-BD or LexA), is co-expressed; specific binding between the bait and aptamer recruits the activation domain to promoter regions, activating reporter genes like HIS3 or lacZ that confer selectable phenotypes, such as growth on histidine-deficient media or colorimetric output. Enriched clones are isolated after multiple rounds of selection, followed by plasmid recovery, sequencing to identify peptide sequences, and validation through independent binding assays, such as pull-downs or surface plasmon resonance, to confirm specificity and affinity. This stepwise process typically yields aptamers with dissociation constants in the nanomolar range for validated targets. For extracellular targets, where intracellular expression may be unsuitable, alternative display methods like phage display or bacterial display are employed. In phage display, random peptides are fused to coat proteins (e.g., pIII on M13 bacteriophage), and libraries of 10^8-10^10 variants are iteratively panned against immobilized targets, eluting and amplifying bound phages in E. coli to enrich high-affinity binders. Bacterial display, using systems like E. coli outer membrane proteins (e.g., INPNC or Lpp-OmpA fusions), offers similar extracellular selection with real-time quantification via flow cytometry, facilitating affinity maturation of peptide aptamers. These methods parallel the in vitro partitioning of SELEX for nucleic acid aptamers but adapt to peptide scaffolds for surface-exposed targets.Emerging Techniques

Computational design of aptamers has emerged as a powerful complement to experimental selection methods, leveraging advances in artificial intelligence and structural biology to predict and optimize aptamer-target interactions. AlphaFold 3, released in 2024 with significant updates in 2025, enables direct modeling of DNA and RNA aptamer structures in complex with protein targets, achieving high accuracy in predicting binding conformations that guide de novo sequence design.[55] Machine learning models, such as AptaTrans, further enhance this process by analyzing large datasets of aptamer sequences to forecast binding affinities and optimize motifs for improved specificity and stability.[56] These computational approaches reduce the reliance on iterative experimental rounds, allowing for rapid screening of vast sequence spaces and integration with generative models that produce novel RNA aptamers tailored to specific targets.[57] In vivo SELEX represents a shift toward selections conducted directly within living animal models, enhancing the physiological relevance of identified aptamers by accounting for complex biological environments such as circulation and tissue barriers. This method involves injecting oligonucleotide libraries into organisms like mice, followed by recovery of enriched sequences from target tissues, yielding aptamers with inherent stability and targeting efficiency.[58] For instance, in vivo SELEX has successfully isolated aptamers capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, as demonstrated in studies using mouse models.[59] Recent advancements in central nervous system delivery include transferrin receptor-targeting RNA aptamers selected via SELEX, with conjugates showing high brain uptake in mouse models.[60] Hybrid methods combine elements of traditional SELEX with innovative partitioning or switching strategies to accelerate discovery and boost specificity. Target-switch SELEX alternates between positive selection against a primary target and negative selection against structurally similar off-targets, enabling the isolation of aptamers with exquisite discrimination, such as those specific to consecutive N-terminal amino acids in peptides.[61] This approach has been applied to generate DNA aptamers that bind with nanomolar affinity while avoiding cross-reactivity, shortening selection timelines to fewer rounds. Complementing this, CE-SELEX employs capillary electrophoresis for high-resolution separation of bound and unbound aptamers, facilitating faster iterations—often completing in 2-4 rounds compared to 8-12 for conventional methods—and higher yields for small-molecule targets.[62] Recent adaptations, including peptide-based CE-SELEX, have extended its utility to cell-surface receptors, isolating aptamers with dissociation constants in the picomolar range.[63]Applications

Therapeutics and Drug Delivery

Aptamers have emerged as promising direct therapeutics due to their high specificity and ability to antagonize key molecular targets involved in disease progression. The first FDA-approved aptamer drug, pegaptanib (Macugen), is a pegylated RNA aptamer that selectively binds vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), inhibiting its interaction with the VEGF receptor to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD).[64] Approved in 2004, pegaptanib demonstrated reduced vision loss in clinical trials, marking a milestone for nucleic acid-based antagonists.[65] In 2023, the FDA approved a second aptamer therapeutic, avacincaptad pegol (Izervay), a pegylated RNA aptamer that inhibits complement protein C5 to slow the progression of geographic atrophy secondary to AMD.[10] This approval highlighted aptamers' potential in complement-mediated diseases, with phase 3 trials showing a 35% reduction in lesion growth over 12 months compared to placebo.[66] Beyond approved drugs, aptamers are advancing in clinical trials as antagonists for various conditions. ApTOLL, a DNA aptamer targeting toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) to modulate neuroinflammation, underwent phase Ib/IIa trials for acute ischemic stroke, where it has shown safety and reduced mortality at 90 days in early studies when combined with thrombolysis.[67] The completed APRIL trial (2025) demonstrated that ApTOLL (0.2 mg/kg) in combination with mechanical thrombectomy significantly reduced final infarct volume, infarct growth, and cerebral edema at 72 hours post-treatment.[68] [69] Similarly, NOX-A12 (olaptesed pegol), an L-RNA aptamer (Spiegelmer) neutralizing CXCL12 to enhance immune cell infiltration, is in phase II trials for cancers including glioblastoma and pancreatic cancer, demonstrating safety and preliminary antitumor activity when combined with radiotherapy or checkpoint inhibitors.[70] In the GLORIA trial for glioblastoma, NOX-A12 with radiotherapy met its primary safety endpoint and showed increased T-cell infiltration in tumors.[31] In drug delivery, aptamers serve as targeting ligands in conjugates and carriers to improve specificity and reduce off-target effects. Aptamer-drug conjugates (ApDCs) link therapeutic payloads to aptamers that bind cell-surface markers overexpressed in diseased tissues, such as nucleolin in cancer cells. A representative example is AS1411-DOX, where the AS1411 aptamer targets nucleolin to deliver doxorubicin selectively to tumor cells, enhancing cytotoxicity while minimizing cardiotoxicity in preclinical models of hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal cancer.[71] This conjugate inhibited tumor growth more effectively than free doxorubicin by promoting receptor-mediated endocytosis and intracellular drug release.[72] Aptamers also enable controlled release in hydrogels, where their binding affinity sequesters drugs until target-triggered dissociation. Aptamer-functionalized hydrogels have been used for localized delivery of angiogenic factors like VEGF, reducing burst release and systemic toxicity in wound healing models by achieving sustained release over days.[73] These systems leverage aptamers' reversible binding to create responsive matrices that release payloads in response to disease-specific biomarkers.[74] As of 2025, two aptamer therapeutics remain FDA-approved, with over 20 candidates in clinical trials across oncology, ophthalmology, and neurology, reflecting growing investment in their therapeutic potential.[75] This pipeline includes antagonists and delivery platforms, underscoring aptamers' advantages in precision medicine despite challenges like nuclease stability, which pegylation and chemical modifications continue to address.[76]Diagnostics and Biosensors