Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

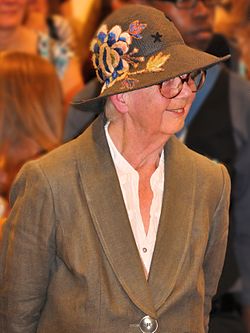

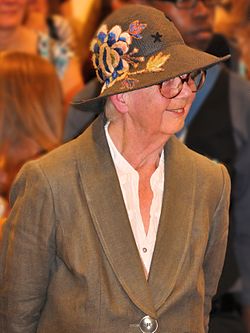

Shirley Hughes

View on Wikipedia

Winifred Shirley Hughes CBE (16 July 1927 – 25 February 2022) was an English author and illustrator. She wrote more than fifty books, which have sold more than 11.5 million copies, and illustrated more than two hundred.[1][2][3][4]

Key Information

Hughes won the 1977 and 2003 Kate Greenaway Medals for British children's book illustration.[4][5][6] In 2007, her 1977 winner, Dogger, was named the public's favourite winning work of the award's first fifty years.[7][8] She won the inaugural BookTrust lifetime achievement award in 2015.[9] She was a recipient of the Eleanor Farjeon Award. She was a patron of the Association of Illustrators.[10]

Early life

[edit]Hughes was born in West Kirby,[11] then in the county of Cheshire (now in Merseyside), on 16 July 1927.[12][13] The daughter of Thomas James Hughes, owner of the Liverpool-based store chain T. J. Hughes and his wife Kathleen (née Dowling), she grew up in West Kirby on the Wirral.[14] She recalled being inspired from childhood by artists like Arthur Rackham and W. Heath Robinson,[15] and later by the cinema and the Walker Art Gallery.[16][17] Particular favourites of hers were Edward Ardizzone, and EH Shepard who illustrated Wind in the Willows and Winnie-the-Pooh.[18]

She enjoyed frequent visits to the theatre with her mother, which gave her a love for observing people and a desire to create.[18]

She was educated at West Kirby Grammar School, but Hughes said she was not a particularly good student academically, and when she was 17, she left school to study drawing and costume design at the Liverpool School of Art.[9][18] In Liverpool she found that societal pressure was put on her to find a husband and then not achieve much with her life. She longed to escape from these claustrophobic expectations, so moved to Oxford in order to attend the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art.[2][18]

Personal life

[edit]After art school she moved to Notting Hill, London.[19] In 1952, she married John Sebastian Papendiek Vulliamy, an architect and etcher, of the Vulliamy family.[20] They had three children together: the journalist Ed Vulliamy, the geneticist Tom Vulliamy, and Clara Vulliamy, who is also a children's book illustrator.[21]

Career

[edit]No one since Rembrandt has so perfectly captured the precarious half-balance of the toddler's toddle. And I don't think anyone ever has depicted ordinary domestic mess so honestly...The parents were also always present in the story – something unusual in children's books. Even more unusual, the siblings in her stories are often really good – even gallant – to each other. The neighbourhood is warm and friendly and multicultural. Her world is our world at its best. The mess and the frizz have their place within a bigger conviction that stories about ordinary children doing ordinary things – getting locked out, losing a toy – could be just as full of courage, wonder and grace as any epic of fairyland.

In Oxford, Hughes was encouraged to work in the picture book format and make lithographic illustrations.[14] However, after graduating she attempted to pursue her ambitions of becoming a theatre designer, and took a job at the Birmingham Rep Theatre. She quickly decided that the "enclosed hothouse" of the theatre world wasn't for her, so followed her former tutor's advice and started working as an illustrator.[18] She began by illustrating the books of other authors, including My Naughty Little Sister by Dorothy Edwards and The Bell Family by Noel Streatfeild.[14][19] The first published book she both wrote and illustrated was Lucy & Tom's Day, which was made into a series of stories.[1] She went on to write over fifty more stories, including Dogger (1977), the Alfie series (1977), featuring a young boy named Alfie and sometimes his sister Annie-Rose, and the Olly and Me series (1993).[21] The Walker Art Gallery in her hometown of Liverpool hosted an exhibition of her work in 2003, which then moved to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.[23][24]

Her most famous book, Dogger, is about a toy dog who is lost by a small boy, but is then reunited with his owner after being found in a jumble sale. This book was inspired by her son, Ed, who lost his favourite teddy in Holland Park. A real Dogger also existed, and was on display along with the rest of her work at her exhibition in London and Oxford.[18]

Hughes illustrated 200 children's books throughout her career, which sold more than 10 million copies.[11] In WorldCat participating libraries, eight of her ten most widely held works were Alfie books (1981 to 2002). The others were Dogger (rank second) and Out and About (1988).[25] Hughes wrote her first novel in 2015, a young-adult book titled Hero on a Bicycle.[9] She was 84 years of age when she wrote this.[18]

Hughes died on 25 February 2022 at her home in London. She was 94, and suffered from a brief illness prior to her death.[11][14] She was paid tribute to by the UK's largest children's reading charity, the BookTrust, who said they were "devastated" by her death and that her "incredible stories and illustrations, from Dogger to Alfie and Lucy and Tom, have touched so many generations and are still so loved. Thank you, Shirley.”[26] Michael Morpurgo, author of War Horse, praised her, noting that she "began the reading lives of so many millions."[11]

Awards

[edit]Dogger (1977), which she wrote and illustrated, was the first story by Hughes to be widely published abroad[17] and it was recognised by the Library Association's Kate Greenaway Medal as the year's best children's book illustration by a British subject.[4] In celebration of the 70th anniversary of the companion Carnegie Medal in 2007, it named one of the top ten Greenaway Medal-winning works by an expert panel and then named the public favourite, or "Greenaway of Greenaways". (The public voted on the panel's shortlist of ten, selected from the 53 winning works 1955 to 2005. Hughes and Dogger polled 26% of the vote to 25% for its successor as medalist, Janet Ahlberg and Each Peach Pear Plum.)[7][8][27][28]

Hughes won a second Greenaway (no illustrator has won three) for Ella's Big Chance (2003), her own adaptation of Cinderella, set in the 1920s.[5][6] It was published in the U.S. as Ella's Big Chance: A Jazz-Age Cinderella (Simon & Schuster, 2004). She was also a three-time Greenaway commended runner up: for Flutes and Cymbals: Poetry for the Young (1968), a collection compiled by Leonard Clark; for Helpers (Bodley Head, 1975), which she wrote and illustrated; and for The Lion and the Unicorn (Bodley Head, 1998), which she wrote and illustrated (Highly Commended).[29][a]

In 1984, Hughes won the Eleanor Farjeon Award for distinguished service to children's literature, in 1999 she was awarded an OBE, and in 2000 she was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. She was also granted an Honorary Fellowship by Liverpool John Moores University[19] and Honorary Degrees by the University of Liverpool in 2004[30] and the University of Chester in 2012.[31]

Booktrust, the UK's largest reading charity, awarded Hughes their first lifetime achievement award in 2015.[9]

Already Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), Hughes was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2017 New Year Honours for services to literature.[32]

Works

[edit]- Moving Molly ISBN 9780099916505

- Bathwater's Hot ISBN 9780688042028

- Noisy ISBN 9780744533774

- When We Went to the Park ISBN 9780744567373

- All Shapes and Sizes ISBN 9780888945167

- Colours ISBN 9780744509243

- Two Shoes, New Shoes ISBN 9780688042073

- The Snow Lady.

- Out and About ISBN 9780688076917

- Dogger ISBN 9781856817646

- Lucy and Tom's Christmas ISBN 9780140504699

- Lucy and Tom at the Seaside ISBN 9780140504699

- Tales of Trotter Street ISBN 9780763600907

- Hero on a Bicycle ISBN 9781406336115

- The Christmas Eve Ghost ISBN 9780763644727

- The Lion and the Unicorn ISBN 9780789425553

- Helpers ISBN 9780099926504

- Angel Mae ISBN 9780744511369

- Dogger's Christmas ISBN 9781782300809

- Jonadab and Rita ISBN 9780370329284

Alfie stories

[edit]- Alfie Gets in First ISBN 9780440841289

- Alfie Gives a Hand ISBN 9780099256076

- Alfie Wins a Prize ISBN 9781862309937

- Alfie's Feet ISBN 9780688016586

- Alfie's Weather ISBN 9780099404255

- An Evening at Alfie's ISBN 9780370305882

- The Big Alfie and Annie Rose Story Book ISBN 9780688076726

- Rhymes for Annie Rose ISBN 9780370319803

Works by other authors, illustrated by Hughes

[edit]- Rust, Doris, All Sorts of Days: Six Stories for the Very Young (Faber and Faber, 1955)

- Corrin, Sara and Stephen, Stories for Eight-Year-Olds (Faber and Faber, 1974)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Today there are usually eight books on the Greenaway shortlist.

According to CCSU, some runners up through 2002 were Commended (from 1959) or Highly Commended (from 1974). There were 99 commendations of both kinds in 44 years; 31 high commendations in 29 years including Hughes and Jane Simmons in 1998.

• No one has won three Greenaway Medals. Among the fourteen illustrators with two Medals, Hughes is one of seven with one book named to the Anniversary Top Ten (1955–2005); one of seven with at least one highly commended runner up (1974–2002); one of six with at least three commendations (1959–2002).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Shirley Hughes – Penguin UK Authors Archived 20 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Random House profile. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ Times Online: It's all about Alfie[dead link]. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ a b c (Greenaway Winner 1978) Archived 6 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Living Archive: Celebrating the Carnegie and Greenaway Winners. CILIP. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ a b (Greenaway Winner 1991) Archived 29 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Living Archive: Celebrating the Carnegie and Greenaway Winners. CILIP. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Shirley Hughes wins second CILIP Kate Greenaway Medal 26 years after her first" Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Press release 9 July 2004. CILIP. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ a b "70 Years Celebration: Anniversary Top Tens" Archived 27 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The CILIP Carnegie & Kate Greenaway Children's Book Awards. CILIP. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ a b "70 Years Celebration: The public's favourite winners of all time!". The CILIP Carnegie & Kate Greenaway Children's Book Awards. CILIP. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d Emily Drabble, Shirley Hughes: I hope books survive, they are wonderful pieces of technology, The Guardian, 6 July 2015.

- ^ "Association of Illustrators". Archived from the original on 12 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Children's author Shirley Hughes dies aged 94". BBC News. 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ The Illustrators: The British Art of Illustration, 1786–2003. Chris Beetles Limited. 2003. p. 187. ISBN 9781871136845.

- ^ International Who's Who of Authors and Writers 2004. Psychology Press. 2003. p. 263. ISBN 9781857431797.

- ^ a b c d Armitstead, Claire (2 March 2022). "Shirley Hughes, children's author and illustrator, dies aged 94". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Drawn to the story". The Guardian. London. 10 July 2004. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Youde, Kate (2 October 2011). "Shirley Hughes: What children want". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ a b Shirley Hughes at Walker Books Archived 1 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Children's author and illustrator Shirley Hughes dies at 94". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Shirley Hughes – Alfie, Dogger and Friends Archived 27 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ "Hughes, Shirley, (Mrs J. S. P. Vulliamy), (born 16 July 1927), free-lance author/illustrator". WHO'S WHO & WHO WAS WHO. 2007. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U21128. ISBN 978-0-19-954088-4. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ a b Booklist of Works by Childrens Book Illustrators Archived 3 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ Cottrell-Boyce, Frank (2 March 2022). "Shirley Hughes Showed Our World at Its Best". New Statesman. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Shirley Hughes, Alfie, Dogger and Friends". Liverpool museums. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum: Features – Exhibitions – More Details". Ashmolean.org. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ "Hughes, Shirley". WorldCat. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Roper, Kerri-Ann (2 March 2022). "Children's author and illustrator Shirley Hughes dies aged 94". www.standard.co.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Pullman wins 'Carnegie of Carnegies'". Michelle Pauli. guardian.co.uk 21 June 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "Carnegie of Carnegies & Greenaway of Greenaways". Christchurch City Libraries Blog. 22 June 2007. Christchurch City Libraries. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ "Kate Greenaway Medal". 2007(?). Curriculum Lab. Elihu Burritt Library. Central Connecticut State University (CCSU). Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ "Popular children's author to receive honorary degree – University of Liverpool". Liv.ac.uk. 8 July 2004. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ "Honorary degree for favourite children's author". chester.ac.uk. 17 December 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "No. 61803". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 2016. p. N9.

Further reading

[edit]- "Shirley Hughes", in Books For Keeps (1984 May), pp. 14–15

- Kate Moody, "A Is for Artists", in Contact (1984 Spring), pp. 24–25

- Shirley Hughes, "Word and Image", in M. Fearn, ed., Only the Best is Good Enough: the Woodfield Lectures 1978–85 (1985)

- Elaine Moss, Part of the Pattern (1986), pp. 107–12

- D. Martin. "Shirley Hughes", in Douglas Martin, The Telling Line: Essays on Fifteen Contemporary Book Illustrators (Julia MacRae Books, 1989), pp. 148–66

- Shirley Hughes, A Life Drawing (The Bodley Head, 2002)

External links

[edit]- Shirley Hughes at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Julia Eccleshare, Shirley Hughes obituary, The Guardian, 2 March 2022

- Ella's big chance: a fairy tale retold in libraries (WorldCat catalog) —immediately, first edition

- Ella's big chance: a Jazz-Age Cinderella in libraries (WorldCat catalog) —immediately, first US edition

- Shirley Hughes at Library of Congress, with 145 library catalogue records

Shirley Hughes

View on GrokipediaEarly life and education

Childhood and family background

Shirley Hughes was born Winifred Shirley Hughes on 16 July 1927 in West Kirby, Cheshire (now part of Merseyside), England.[2][3] She was the youngest of three daughters in a middle-class family; her father, Thomas J. Hughes, founded and owned the T.J. Hughes department store in Liverpool but died by suicide in 1933, when Shirley was five years old.[3][4][5] Her mother, Kathleen Hughes (née Dowling), who came from an Irish family, then raised the girls alone in a quiet suburban home on the Wirral Peninsula.[3] The coastal environment of West Kirby, a seaside town near Liverpool, shaped Hughes's early observational skills, exposing her to everyday scenes of family life, nature, and local community interactions that would inform her later artistic focus on ordinary moments.[6] From a young age, she showed a strong interest in drawing, creating self-taught sketches of her family, the surrounding landscape, and town activities to occupy her time in the all-female household.[2] Hughes also developed an early passion for storytelling by making up narratives, illustrating them with her drawings, and staging plays with her sisters, which nurtured her abilities in visual and narrative expression.[2] Hughes's childhood and early adolescence unfolded amid the 1930s and 1940s in Britain, including the home-front challenges of World War II, as the Wirral area near Liverpool endured the Blitz bombings starting in 1940.[4] Rather than being evacuated, she remained at home with her mother and sisters, witnessing the resilience of daily domestic life under wartime rationing, air raid precautions, and community solidarity.[7] These experiences of uncertainty and perseverance in a coastal town fostered her appreciation for themes of everyday endurance that permeated her future illustrations.[3]Formal artistic training

Hughes attended West Kirby Grammar School from 1935 to 1943, where she pursued artistic interests alongside a standard academic curriculum, though she later described herself as not particularly gifted in scholarly subjects.[8][9] The school's emphasis on narrative elements in education helped foster her early creative development, providing a foundation for her visual storytelling.[10] At the age of 17 in 1944, Hughes enrolled at the Liverpool School of Art, embarking on formal training in drawing and costume design during the late wartime and immediate post-war years.[11][12] Her studies there, lasting approximately one to one-and-a-half years, focused on fashion and dress design with an eye toward theatre costumes, building essential skills in observational drawing and figure work.[10][4] This period solidified her habit of sketching from life, a practice she maintained throughout her career.[13] Following her time in Liverpool, Hughes briefly trained in set and costume design at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, but found the theatrical environment unsuitable and decided to pursue fine art instead.[11] She then transferred to the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art at Oxford University, where she studied for four years in the late 1940s.[10][14] The program provided advanced instruction in fine arts, with a strong emphasis on classical techniques such as life drawing and painting, which honed her ability to capture human forms with precision and empathy.[13][11] During this immersive academic environment, she benefited from exposure to intellectual discussions and art history lectures, including those by Kenneth Clark on European painting traditions.[10] A key aspect of her Ruskin experience involved influential mentors who shaped her path toward illustration; a lithography tutor encouraged her to view the page as a theatrical stage, while another tutor suggested she pursue illustration over costume design.[11][15] She also drew inspiration from British illustrators like Arthur Rackham, whose intricate, atmospheric style informed her own detailed line work and ties to narrative fantasy, elements she encountered and appreciated amid her formal studies.[16][1] This blend of classical training and targeted influences equipped her with the technical proficiency central to her later professional output.[17]Personal life

Marriage and family

In 1952, Shirley Hughes married John Vulliamy, an architect and etcher.[11] Their marriage lasted until Vulliamy's death in 2007.[18] The couple settled in a Victorian house in Notting Hill, West London, shortly after their wedding, where they established a supportive home environment that allowed Hughes to balance domestic responsibilities with her artistic pursuits.[11] Vulliamy provided financial stability as the primary earner, enabling Hughes to focus on her creative work amid family life.[19] Hughes and Vulliamy had three children: sons Ed Vulliamy, born in 1954 and later a journalist, and Tom Vulliamy, born around 1956 and a geneticist, followed by daughter Clara Vulliamy, born in 1962 and also a children's book illustrator.[20][21][22] The family raised their children in their Notting Hill home, which overlooked a communal garden where the toddlers played, offering Hughes daily opportunities to observe their movements, interactions, and fleeting emotions during unstructured playtime.[11] Domestic routines centered around the kitchen table, where meals interrupted creative sessions and family brainstorming sessions unfolded with laughter, fostering a hands-off yet encouraging atmosphere—Hughes refrained from reading her stories aloud to her children or formally teaching them to draw, allowing their imaginations to develop independently.[23] This period of raising young children in a vibrant West London neighborhood deeply informed Hughes's empathetic perspective on childhood, as she spent hours at nearby playgrounds watching toddlers navigate uncertainty and joy, insights drawn from her own family's rhythms rather than external study.[18] The home remained a hub of creativity and warmth, with Vulliamy's later etching hobbies complementing the family's artistic inclinations, and Hughes later noting how her grandchildren brought similar delight and humor to her later years.[24][25]Death

Shirley Hughes died on 25 February 2022 at her home in London, England, at the age of 94.[26] She passed away peacefully after a short illness, as confirmed by her family.[1] In her final years, Hughes remained active in her creative pursuits, releasing Dogger's Christmas in 2020, before living more quietly in London.[1] Her family announced her death to the PA news agency, stating that she had died "peacefully at home after a short illness," and expressed their profound sadness while noting her enduring love for family and storytelling.[27]Career

Early illustrations and influences

After completing her formal training at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art in Oxford in 1952, Shirley Hughes settled in London to seek freelance illustration opportunities in the burgeoning post-war British publishing scene. The period following World War II marked a vibrant resurgence in children's literature and illustration, with expanded library services and a demand for engaging visual storytelling that reflected everyday domestic life amid recovering social norms.[11][28] Hughes's professional debut came in 1950 with her first commission to illustrate The Hill War by Olivia Fitzroy, a novel published by William Collins, marking her entry into book illustration while she experimented with line drawings suitable for educational and narrative contexts. Throughout the 1950s, she secured further commissions for children's books, including Dorothy Edwards's My Naughty Little Sister in 1952 and a series of titles by Doris Rust: A Week of Stories (1953), A Story a Day (1954), and All Sorts of Days: Six Stories for the Very Young (1955), all published by Faber and Faber. These early works showcased her developing style, characterized by simple yet expressive pen-and-ink illustrations that captured the whimsy and realism of childhood, often drawing on her training in costume design to infuse scenes with period-appropriate detail. She also contributed illustrations to magazines and educational materials during this time, honing her ability to convey narrative through minimalistic yet evocative visuals.[29][30][31] In her nascent career, Hughes drew significant inspiration from prominent British illustrators whose works shaped the post-war aesthetic of children's literature. She frequently cited W. Heath Robinson for his intricate, humorous line work in books like A Midsummer Night's Dream, Edward Ardizzone for his economical pencil sketches that evoked emotional depth with few strokes, and E.H. Shepard for the seamless integration of illustrations into text in classics such as Winnie-the-Pooh. These encounters, rooted in her childhood reading and reinforced through professional exposure, encouraged her to prioritize storytelling and observational detail over ornate complexity, aligning with the era's shift toward accessible, relatable imagery in a time of cultural reconstruction.[11][13] By the early 1960s, following her marriage in 1952 and the arrival of her first children, Hughes committed to full-time illustration for children's books, building on her 1950s foundation to produce work for authors like Noel Streatfeild, including The Bell Family (1954). This phase solidified her reputation, leading to a prolific output that ultimately encompassed illustrations for over 200 books, emphasizing her role in evolving the genre through authentic depictions of family life.[11][13]Major authored series and books

Shirley Hughes began her career as an author-illustrator with the Lucy & Tom's Day series in the early 1960s, starting with Lucy & Tom's Day published in 1960, which captured the everyday routines and domestic adventures of young siblings inspired by her own children.[1] The series, including later titles like Lucy and Tom's Christmas in 1981, focused on simple toddler experiences such as mealtimes, play, and family interactions, establishing Hughes' signature style of warm, relatable narratives for preschool audiences. One of Hughes' most enduring contributions was the Alfie series, launched with Alfie Gets in First in 1981, which followed the everyday mishaps and joys of a young boy named Alfie and his family in an urban British setting.[1] Core installments, such as An Evening at Alfie's in 1984 and Alfie and the Birthday Surprise in 1997, explored preschool themes like sibling dynamics, birthday celebrations, and neighborhood explorations, with the series expanding into the 1990s and beyond, including Alfie Wins a Prize in 2004.[32] The Alfie books, numbering over a dozen by the end of her career, accounted for a significant portion of her output and contributed to the popularity of her work among young readers.[33] In 1977, Hughes published the standalone picture book Dogger, a poignant story about a young boy searching for his lost toy dog at a fair, ultimately aided by his sister in a moment of empathy and family bonding.[1] The book received immediate acclaim for its emotional depth and realistic portrayal of childhood loss and resolution, later inspiring a sequel, Dogger's Christmas, in 2020. Hughes continued to develop her authorship with other notable standalones and series, including the Olly and Me series beginning with Hiding in 1994, followed by titles like Olly and Me in 2004, which depicted the imaginative world of a toddler girl and her baby brother through playful, rhyming vignettes of daily discovery.[34] At the age of 85, she ventured into longer-form storytelling with her first novel, Hero on a Bicycle, published in 2012, a World War II adventure set in occupied Italy following a British family's involvement in the resistance through the eyes of two children.[1] Over her lifetime, Hughes authored more than 50 books, with global sales exceeding 11 million copies, particularly driven by the enduring appeal of series like Alfie among families and educators.[1]Later works and exhibitions

In the 2000s, Hughes expanded her oeuvre beyond her signature picture books, venturing into retellings and short novels that reflected her evolving interests in historical settings and family dynamics. Her 2003 publication Ella's Big Chance, a jazz-age reinterpretation of the Cinderella tale, earned her a second Kate Greenaway Medal and showcased her ability to infuse classic narratives with vibrant, period-specific illustrations of fashion and urban life.[1] Similarly, The Lion and the Unicorn (1998) drew on her wartime childhood experiences to depict a young girl's life in 1940s Liverpool amid air raids, blending tender prose with evocative drawings of resilience and everyday heroism.[3] Hughes's later career marked a shift toward longer-form storytelling, including her first full novel, Hero on a Bicycle (2012), set in Nazi-occupied Florence and exploring themes of resistance and moral complexity through the eyes of an English family. This work, illustrated with her characteristic warmth, highlighted her transition to chapter books for older children. She continued producing into her later years, with Ruby in the Ruins (2018) portraying postwar London reconstruction through a child's perspective on loss and renewal, and co-authoring the Dixie O'Day adventure series starting in 2013, which featured lively tales of friendship and mishaps illustrated in her familiar style. Despite her advancing age, Hughes maintained a steady output, culminating in poetry anthologies and adaptations that reinforced her focus on emotional depth in family narratives.[35][36] Public recognition of Hughes's enduring contributions came through several major exhibitions in the 2000s and 2010s. A 2003 retrospective at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, titled Shirley Hughes, Alfie, Dogger and Friends, displayed original artwork from her beloved series, attracting families and celebrating her influence on children's literature. This was followed by an 80th-birthday exhibition, A Life Drawing, at London's Illustration Cupboard in 2007, featuring sketches and finished pieces from across her career. In 2016, The Enchanting World of Shirley Hughes at the same venue showcased her colorful character studies and thematic depth, while a 2017 retrospective for her 90th birthday further highlighted her prolific legacy. These shows underscored her meticulous draftsmanship and observational skill, drawing crowds eager to revisit her worlds.[12][37][38][39] Over her lifetime, Hughes illustrated more than 200 books, many translated into over 30 languages and adapted for international audiences, including stage productions of works like Dogger. Her post-2000 output contributed to a career total exceeding 11.5 million copies sold worldwide, cementing her as a pivotal figure in children's illustration with themes that evolved from domestic joys to broader historical reflections.[40][1]Works

Books written and illustrated by Hughes

Shirley Hughes authored and illustrated over 50 books for children, primarily picture books that capture everyday family life with warmth and humor. Her works often feature relatable young protagonists navigating preschool and early school experiences, published mainly by Bodley Head in her early career and later by Walker Books, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing. These books emphasize themes of sibling relationships, daily routines, and gentle adventures, with many undergoing multiple reprints and editions to reach new generations.[40]Picture Books

Hughes's standalone picture books form the foundation of her oeuvre, beginning with simple narratives for very young readers. Notable early examples include Lucy and Tom's Day (1960), which depicts a sibling pair's ordinary activities, and Dogger (1977), a beloved tale of a lost toy that earned the Kate Greenaway Medal. Later picture books such as Up and Up (1993), a wordless exploration of imagination, and Don't Want to Go! (2009), addressing separation anxiety, continue her tradition of empathetic storytelling. These were published by Walker Books, with several titles reissued in board book formats for toddlers.[11][41][40]Series Overviews

Hughes developed several enduring series centered on preschool-aged children, providing continuity through recurring characters and familiar settings. The Alfie series, launched in 1981 with Alfie Gets in First and spanning more than 15 titles into the 2010s (including Alfie Gives a Hand (1983), Alfie's Feet (1982), and Alfie's Christmas (2011)), focuses on a young boy named Alfie and his family, highlighting preschool challenges like making friends and family outings; the series was published by The Bodley Head and later Walker Books.[42][32] The Olly and Me series (1994–2009), comprising titles like Hiding (1994), Bouncing (2004), and Olly and Me 1-2-3 (2009), explores sibling dynamics from the perspective of a toddler observing her older brother Olly, emphasizing play and discovery; these were issued by Walker Books.[34][36] The Lucy & Tom series, starting with Lucy and Tom's Day (1960) and extending to books like Lucy and Tom Go to School (1973), Lucy and Tom's ABC (1984), and Lucy and Tom at the Seaside (1976), portrays the daily routines of two young siblings, introducing concepts like counting and letters through gentle narratives; early volumes appeared under Victor Gollancz, with later editions by Walker Books.[43][44]Novels and Later Works

In her later career, Hughes ventured into novels for older readers, drawing on historical settings. Hero on a Bicycle (2012), set in Nazi-occupied Italy, follows a family's involvement in the Resistance, marking her debut in chapter-book fiction and published by Walker Books. This was followed by Whistling in the Dark (2015), a tale of friendship amid the Liverpool Blitz, also from Walker Books. Additionally, Hughes compiled poetry anthologies like Out and About: A First Book of Poems (1988), featuring seasonal verses for young children, published by Walker Books.[45][46][47][48]Books illustrated for other authors

Throughout her career, Shirley Hughes illustrated over 200 books for other authors, spanning from her early professional work in the 1950s to later collaborations in the 1990s, often adapting her warm, observational style to complement narratives of everyday childhood and family life.[40] Her contributions emphasized collaborative storytelling, where her illustrations enhanced the text without overshadowing it, drawing on influences from classic children's literature to bring authenticity to characters and settings.[6] Early collaborations marked Hughes's entry into publishing, beginning with simple, domestic tales for young readers. Another key early partnership was with Noel Streatfeild for The Bell Family (1954), where Hughes's illustrations depicted the bustling life of a large, artistic household, adding visual warmth to the story of family resilience and creativity.[49] In 1955, she provided black-and-white line drawings for All Sorts of Days: Six Stories for the Very Young by Doris Rust, a collection of gentle vignettes about children's daily adventures, published by Faber and Faber.[50] This debut work showcased her emerging talent for capturing fleeting moments of play and mischief. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, she illustrated editions of Dorothy Edwards's beloved My Naughty Little Sister series, infusing the mischievous protagonist's escapades with lively, expressive sketches that highlighted sibling dynamics and household chaos.[51] In her mid-career, Hughes frequently contributed to anthologies and story collections, adapting her style to diverse voices in poetry and short fiction. For the 1972 The First Margaret Mahy Story Book, she created evocative images for Mahy's whimsical tales and poems, blending fantasy with relatable child perspectives in a Dent publication.[52] Similarly, in 1974, she illustrated Stories for Eight-Year-Olds edited by Sara and Stephen Corrin, a Faber anthology of classic and contemporary short stories that included works by authors like Joan Aiken, with Hughes's drawings providing continuity across the varied narratives of adventure and humor.[53] These projects highlighted her versatility in partnering with established writers, such as Mahy and the Corrins, to elevate collections that introduced young readers to broader literary traditions. Later examples from the 1980s and 1990s included illustrations for Alison Uttley's rustic tales and Ian Serraillier's poetic works, maintaining her focus on timeless themes without venturing into her own authored territory.[54]Style and influences

Illustration techniques

Shirley Hughes primarily employed traditional mediums such as pen and ink, gouache, watercolor, pencil, and oil pastels in her illustrations, avoiding digital tools throughout her career.[7][55][29] For black-and-white line work, she favored a dip or scratch pen with Indian ink to achieve precise, expressive lines that conveyed movement and detail, while gouache—squeezed directly from tubes—and fine brushes were used for colored pieces to build tone and atmosphere.[55][12] These materials allowed her to create layered, textured visuals rooted in observational drawing. Her characteristic techniques included cross-hatching to add depth and texture, particularly in rendering fabrics, shadows, and everyday objects, enhancing the realism of her scenes.[56] Hughes placed a strong emphasis on accurate depictions of toddler anatomy, capturing the proportions, gestures, and subtle expressions of young children to convey their emotions and agency, such as hesitant stances or playful crouches.[7][13] In composition, she orchestrated dynamic layouts that highlighted domestic chaos—cluttered homes filled with scattered toys, untied shoelaces, and interrupted routines—using line work influenced by comics to propel narrative flow and energy.[7][57] Hughes's process began with extensive sketching from life, filling notebooks with quick observations of her own children and neighborhood toddlers in parks and playgrounds, which informed her character designs without relying on specific models.[55][7] She developed rough dummies by hand to integrate text and images, refining pencil underdrawings before final inking or painting. Over time, her style evolved from the highly detailed, realistic illustrations of her early career—such as those in Dogger—to looser, more empathetic lines in later works, allowing greater fluidity while maintaining her recognizable warmth and precision.[55][13]Themes and inspirations

Shirley Hughes's works recurrently explore the subtle magic embedded in everyday childhood experiences, portraying ordinary moments such as lost toys or sibling interactions as sources of wonder and emotional depth.[7] Central to her narratives are strong family bonds, depicted through reassuring parental figures and the rhythms of domestic life, often set against the backdrop of 1970s and 1980s urban London, where resilience emerges in small acts of kindness amid routine challenges.[58] Her illustrations of multicultural neighborhoods, as seen in series like Tales of Trotter Street, highlight diverse community interactions in shared urban spaces, reflecting the changing social fabric of post-war Britain.[59] Hughes drew heavily from her personal life for inspiration, particularly the chaotic energy and messiness of toddlers, which she observed while raising her three children and incorporated as a composite of "all the toddlers I’ve ever known."[60] Culturally, her WWII-era childhood in Liverpool influenced the grounded realism of her stories, while later works like Ella's Big Chance incorporated 1920s jazz-age elements, evoking the era's vibrant social and musical scenes to reimagine folktales with historical flair.[7] Literarily, she favored realistic depictions over fantastical elements, drawing from traditional folktales but adapting them to emphasize authentic emotional discovery rather than whimsy.[58] Socially, Hughes empowered young protagonists by granting them agency in navigating their worlds, from minor conflicts to community engagements, fostering a sense of independence within supportive environments.[59] This approach distinguished her from contemporaries who leaned toward escapist fantasy, as Hughes prioritized honest portrayals of domesticity and urban multiculturalism, capturing the unvarnished joys and tensions of real family life in a diverse, evolving London.[7]Awards and honors

Kate Greenaway Medals

The Kate Greenaway Medal, established in 1955 by the Library Association (now CILIP), is the United Kingdom's oldest and most prestigious award for distinguished illustration in a children's book, recognizing works that create an exceptional reading experience through artwork.[61] Awarded annually to a British or Irish illustrator, it honors books published in the UK and is named after the 19th-century artist Kate Greenaway, renowned for her influential children's illustrations.[61] Shirley Hughes received the Kate Greenaway Medal in 1977 for Dogger, her picture book about a young boy and his beloved stuffed dog toy that goes missing during a family outing to a school fete, exploring themes of loss, family support, and the emotional bonds of childhood possessions.[11] The win highlighted Hughes's ability to capture everyday domestic life with warmth and detail, cementing Dogger's status as a classic in children's literature.[62] Following the award, Dogger saw a significant boost in sales, including translations into 13 languages and international acclaim that expanded Hughes's reach beyond the UK market.[63] Hughes became one of only a handful of illustrators to win the medal twice when she received it again in 2003 for Ella's Big Chance, an innovative retelling of the Cinderella fairy tale set in the 1920s Jazz Age, where the protagonist is a talented dressmaker who chooses self-reliance over romance.[64] At age 76, this second victory marked a notable resurgence in her career, reaffirming her versatility in adapting classic narratives with modern, empowering twists through vibrant, period-inspired illustrations.[65] The award underscored her enduring influence, as multiple wins are rare among recipients like Anthony Browne and Quentin Blake.[61] In 2007, to celebrate the medal's 50th anniversary, a public poll by CILIP voted Dogger the nation's favorite Kate Greenaway-winning book of all time, reflecting its lasting appeal and the immediate cultural impact of Hughes's 1977 triumph.[66]Other literary and honorary awards

In addition to her Kate Greenaway Medals, Shirley Hughes received the Other Award from the Children's Rights Workshop in 1975 for her book Helpers, recognizing its non-sexist portrayal of family life and domestic roles.[1] This accolade highlighted her early contributions to inclusive children's literature during the 1970s.[17] Hughes was awarded the Eleanor Farjeon Award in 1984 by the Children's Book Circle for her distinguished service to children's books over two decades.[2] This career-spanning honor celebrated her dual role as author and illustrator, emphasizing her influence on the field.[1] She was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2000.[67] In 2014, she received the Once Upon a World Children's Book Award from the Simon Wiesenthal Center/Museum of Tolerance for Hero on a Bicycle.[68] In 2015, she became the inaugural recipient of the BookTrust Lifetime Achievement Award, marking over 60 years of creating beloved works that captured everyday childhood experiences.[69] The award underscored her prolific output of more than 50 books and her enduring impact on young readers.[70] Hughes received an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1999 New Year Honours for services to children's literature.[2] She was later promoted to Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2017 New Year Honours for her broader contributions to literature.[2] For her academic recognition, Hughes was conferred an honorary Doctor of Letters (DLitt) by the University of Liverpool in 2004.[71] In 2012, the University of Chester awarded her another honorary degree, acknowledging her cultural significance in the region.[72]Legacy

Impact on children's literature

Hughes's contributions to children's literature are evidenced by the widespread commercial success of her works, with over 11 million copies sold worldwide across more than 50 books she authored and illustrated, alongside her illustrations for nearly 200 others.[73] Her books, including the beloved Dogger, have been translated into more than 30 languages, extending their reach to international audiences and making everyday childhood experiences accessible beyond English-speaking contexts.[74] This global dissemination underscores her role in broadening the genre's appeal, as her stories resonated with families in diverse cultural settings through relatable depictions of family life and play.[7] One of Hughes's key innovations was pioneering realistic narratives centered on toddlers and young children, capturing the mundane yet profound dramas of daily life—such as losing a favorite toy or navigating sibling dynamics—with authenticity and emotional depth.[59] Unlike many contemporaries who favored fantastical elements, her focus on unadorned, child-height perspectives brought a grounded realism to picture books, emphasizing small-scale adventures that mirrored real-world toddler experiences.[7] She also bridged the gap between picture books and early chapter books through transitional works like the Alfie series and short illustrated novels, easing young readers into longer formats while maintaining visual storytelling to support emerging literacy.[75] Hughes's portrayals of childhood offered a quintessentially English lens—featuring terraced houses, rainy streets, and post-war domesticity—yet achieved universal resonance by highlighting timeless aspects of growing up, such as curiosity, resilience, and familial bonds.[4] Her inclusion of multicultural characters in urban English settings predated widespread calls for diversity in children's literature, influencing subsequent creators to incorporate varied representations of family and community in their narratives.[76] This approach not only reflected the evolving demographics of mid-20th-century Britain but also encouraged a more inclusive storytelling tradition that celebrated ordinary lives across cultural lines.[59] In the industry, Hughes played a mentorship role, notably through her collaboration with her daughter Clara Vulliamy, a fellow children's author-illustrator, on projects like the Dixie O'Day series, which modeled intergenerational creative partnerships.[19] Her extensive archive, preserved at institutions such as the Bodleian Library, has supported exhibitions that showcase her techniques and inspire ongoing scholarship in illustration, ensuring her methods remain a reference for emerging artists in the field.[77]Posthumous tributes and recognition

Following Shirley Hughes's death on 25 February 2022, major British media outlets published extensive obituaries highlighting her profound influence on children's literature. The BBC reported her passing, noting her creation of beloved characters like Alfie and Dogger, and emphasized her books' enduring appeal to families worldwide.[26] The Guardian's obituary described her as an illustrator whose "everyday stories of early childhood cast a happy glow across generations of family life," crediting her with over 50 authored books and illustrations for 200 others, many still in print.[1] Her family issued a statement confirming she "died peacefully at home after a short illness," and praised her work as "adored by generations of families," underscoring her high regard among peers for capturing the warmth of domestic life.[26] Tributes from prominent figures poured in, with author Michael Morpurgo stating in The Guardian that "Shirley must have begun the reading lives of so many millions," positioning her stories as foundational for young readers.[78] BookTrust, the UK's largest children's reading charity, expressed devastation at her loss, affirming that her illustrations and narratives had "touched so many generations."[26] Other writers, including Philip Pullman, hailed her as "inimitable, beloved, immortal," for her unique ability to depict childhood with empathy and detail.[78] Posthumous events included archival preservation efforts, with the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford University receiving additional materials from her family in 2022 to expand her existing collection, ensuring her sketches, manuscripts, and correspondence remain accessible for study.[77] In April 2023, her son Tom Vulliamy donated hundreds of her books, including copies of Dogger, to libraries in Ukraine amid the ongoing conflict, bringing comfort to displaced children through her stories of family resilience.[79] By January 2025, her archive was officially classified as cultural heritage by the UK government, alongside that of John le Carré, recognizing its national significance and protecting it from export.[80] In 2025, the Shirley Hughes Sketchbook Award was launched by Orange Beak Studio to celebrate her observational drawing style, with the first winner, Liz Anelli, announced in July.[81] Hughes's work continues to be celebrated for its timelessness, with her books routinely reprinted and included in core collections of children's literature, reflecting ongoing appreciation for her gentle portrayal of everyday joys and challenges.[1] As of 2025, her illustrations are seen as exemplars of observational storytelling, influencing new generations of readers and creators without major new adaptations or awards emerging since her death.[78]References

- https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q21464926