Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

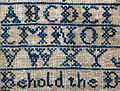

Smocking

View on Wikipedia

Smocking is an embroidery technique used to gather fabric so that it can stretch. Before elastic, smocking was commonly used in cuffs, bodices, and necklines in garments where buttons were undesirable. Smocking developed in England and has been practised since the Middle Ages and is unusual among embroidery methods in that it was often worn by labourers. Other major embroidery styles are purely decorative and represented status symbols. Smocking was practical for garments to be both form fitting and flexible, hence its name derives from smock — an agricultural labourer's work shirt.[1] Smocking was used most extensively in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[2]

Materials

[edit]Smocking requires lightweight fabric with a stable weave that gathers well. Cotton and silk are typical fiber choices, often in lawn or voile. Smocking is worked on a crewel embroidery needle in cotton or silk thread and normally requires three times the width of initial material as the finished item will have.[3] Historically, smocking was also worked in piqué, crepe de Chine, and cashmere.[4] According to Good Housekeeping: The Illustrated Book of Needlecrafts, "Any type of fabric can be smocked if it is supple enough to be gathered."[2]

Fabric can be gathered into pleats in a variety of ways.

Early smocking, or gauging, was done by hand. Some embroiderers also made their own guides using cardboard and an embroidery marking pencil.[2] By 1880, iron-on transfer dots were available and advertised in magazines such as Weldon's. The iron-on transfers places evenly spaced dots onto the wrong side of the fabric, which were then pleated using a regular running stitch.

Since the early 1950s, pleating machines have been available to home smockers. Using gears and specialty pleater needles, the fabric is forced through the gears and onto the threaded needles. Pleating machines are typically offered in 16-row, 24-row and 32-row widths.

Methods

[edit]

Smocking refers to work done before a garment is assembled. It usually involves reducing the dimensions of a piece of fabric to one-third of its original width, although changes are sometimes lesser with thick fabrics. Individual smocking stitches also vary considerably in tightness, so embroiderers usually work a sampler for practice and reference when they begin to learn smocking.[2]

Traditional hand smocking begins with marking smocking dots in a grid pattern on the wrong side of the fabric and gathering it with temporary running stitches. These stitches are anchored on each end in a manner that facilitates later removal and are analogous to basting stitches. Then a row of cable stitching (see "A") stabilizes the top and bottom of the working area.[5]

Smocking may be done in many sophisticated patterns.[6]

Standard hand smocking stitches are:

A. Cable stitch: a tight stitch of double rows that joins alternating columns of gathers.[7]

B. Stem stitch: a tight stitch with minimum flexibility that joins two columns of gathers at a time in single overlapping rows with a downward slope.[8]

C. Outline stitch: similar to the stem stitch but with an upward slope.[8]

D. Cable flowerette: a set of gathers worked in three rows of stitches across four columns of gathers. Often organized in diagonally arranged sets of flowerettes for loose smocking.[9]

E. Wave stitch: a medium density pattern that alternately employs tight horizontal stitches and loose diagonal stitches.[10]

F. Honeycomb stitch: a medium density variant on the cable stitch that double stitches each set of gathers and provides more spacing between them, with an intervening diagonal stitch concealed on the reverse side of the fabric.[11]

G. Surface honeycomb stitch: a tight variant on the honeycomb stitch and the wave stitch with the diagonal stitch visible, but spanning only one gather instead of a gather and a space.[12]

H. Trellis stitch: a medium density pattern that uses stem stitches and outline stitches to form diamond-shaped patterns.[12]

I. Vandyke stitch: a tight variant on the surface honeycomb stitch that wraps diagonal stitches in the opposite direction.[13]

J. Bullion stitch: a complex knotted stitch that joins several gathers in a single stitch. Organized similarly to cable flowerettes.[13]

- Smocker's knot: (not depicted) a simple knotted stitch used to finish work with a thread or for decorative purposes.[9]

Organizations

[edit]Smocking organizations and groups include the Smocking Arts Guild of America (SAGA),[14] the Smocking Arts Guild of NSW,[15] and the Embroiderers' Guild of America. The V and A East Storehouse in London has many examples of smocking that can be viewed upon request.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Reader's Digest, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d Good Housekeeping, p. 146.

- ^ Reader's Digest, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Gilman, Elizabeth Hale (1917). "Things Girls Like to Do". Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ Reader's Digest, pp. 161–162.

- ^ "2005 SAGA Glossary - Smocking Terms" (PDF). Smocking Arts Guild of America. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ Reader's Digest, p. 163.

- ^ a b Reader's Digest, p. 164.

- ^ a b Reader's Digest, p. 165.

- ^ Reader's Digest, p. 166.

- ^ Reader's Digest, p. 167.

- ^ a b Reader's Digest, p. 168.

- ^ a b Reader's Digest, p. 169.

- ^ "About SAGA". Smocking Arts Guild of America. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ "About Us". Smocking Arts Guild of NSW. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ Brocket, Jane (2025-09-21). "gathering stitches and thoughts". yarnstorm. Retrieved 2025-10-23.

Bibliography

[edit]- The Reader's Digest Association, Complete Guide to Embroidery Stitches, Pleasantville, New York: Marabout, 2004. ISBN 0-7621-0658-1

- Ed. Cecilia K. Toth, Good Housekeeping: The Illustrated Book of Needlecrafts, New York: Hearst Books, 1994. ISBN 1-58816-035-1