Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cutwork

View on Wikipedia

Cutwork or cut work, also known as punto tagliato in Italian, is a needlework technique in which portions of a textile, typically cotton or linen,[1] are cut away and the resulting "hole" is reinforced and filled with embroidery or needle lace.

Cutwork is related to drawn thread work. In drawn thread work, typically only the warp or weft threads are withdrawn (cut and removed), and the remaining threads in the resulting hole are bound in various ways. In other types of cutwork, both warp and weft threads may be drawn. Cutwork is considered the precursor of lace.[2]

Different forms of cutwork are or have traditionally been popular in a number of countries. Needlework styles that incorporate cutwork include broderie anglaise, Carrickmacross lace, whitework, early reticella, Spanish cutwork, hedebo,[3] and jaali which is prevalent in India.

There are degrees of cutwork, ranging from the smallest amount of fabric cut away (Renaissance cutwork) to the greatest (Reticella cutwork). Richelieu cutwork in the middle.[4]: 378

Eyelet fabrics

[edit]

Eyelet is both a type of cutwork embroidery and the fabric made from embroidering cutwork. Cutwork is used to create eyelet fabrics by cutting small holes and embroidering the edges of those holes to finish them. Common base fabrics include broadcloth, batiste, lawn, linen, organdy, and pique.[5] Leather and pleather[5] can also be used in cutwork, but often they are not then finished with embroidery.

The amount and closeness of stitching, as well as the quality of the background fabric, may vary in different types. Eyelet fabrics are an ever-popular type of fabric[6] and are used for both entire clothing pieces or for trimming pieces made from other cloth. It is also commonly used to trim bedding, curtains, and table linens.[5]

Hand-sewn eyelet is labor-intensive to produce by hand and traditionally was only used as trim or, when used in large pieces, only for expensive items; machine-made eyelet fabric made the fabric affordable for everyday wear.

History

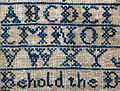

[edit]The cutwork technique originated in Italy at the time of the Renaissance, approximately the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries.[7] In Renaissance embroidery and Richelieu work, the design is formed by cutting away the background fabric.[8] In the Elizabethan era, cutwork was incorporated into the design and decoration of some ruffs. In a fashion sense, this type of needlework has migrated to countries around the world,[9] including the United Kingdom, India, and the United States. Dresden samplers contained white cutwork, along with needle lace.[10]: 195 Cutwork is still prevalent in fashion today, and although they are different, cutwork is commonly mistaken for lace. The eyelet pattern is one of the more identifiable types of cutwork in modern fashion. In eyelet embroidery, the design comes from the holes, rather than the fabric.[8]

Traditional cutwork by country

[edit]Czech Republic

[edit]Densely worked cutwork was traditional in many parts of the Czech Republic. Motifs might be circular, arc, or leaf-shaped. Because the motifs were often so close together, the embroidery looked like lace once all the motif centers were cut away.[11]: 120

Cyprus

Lefkaritika is the characteristic type of embroidery art in Cyprus, dating back to at least the fourteenth century. The first Lefkara Lace was made from the local white cotton fabric produced in Cyprus. A combination of stitches and cuts is used. Women embroideresses in Pano Lefkara, called "ploumarisses" organised their production from home. Men from Lefkara, called "kentitarides", were merchants and they traveled across Europe and Egypt and other areas. [12]

Italy

[edit]Embroidery pattern books after 1560 focused heavily on cutwork, as it became very popular in Italy. Initially, scrolling patterns worked in punto in aria were most evident, changing at the end of the century to reticella. The punto in aria technique involved laying threads over a linen ground, and then cutting the ground away. It was often use for freer patterns than the more geometric reticella, where squares of the ground cloth were cut out and embroidery was then applied.[13]: 138

Madeira

[edit]in the 1850s, an Englishwoman, Miss Phelps, arrived in Madeira to recuperate, and she gave lessons in broderie anglaise. In the 1920s, after noting many skilled needlewomen. the Madeira Embroidery Guild was formed. Amongst its purposes was to set the pay and standards for embroiderers on the island. As indicated by the existence of the guild, many women in Madeira engaged in embroidery as a way of earning money for their families.[14]

Netherlands

[edit]Cutwork was popular throughout the Netherlands. An especially fine form of cutwork is called snee werk, used for decorating clothing such as aprons and blouses, and household items such as pillowcases.[4]: 185

Poland

[edit]The eyelet form of cutwork was popular in the Polish countryside from the 1700s, if not earlier. It was used to decorate costumes and textiles for the home. The execution of this hand embroidery reached its height in the late 1800s, a prosperous time with more money for clothing. Eyelet embroidery was found on men's clothing as well as women's. For those who couldn't afford larger garments, eyelet collars that could be used to adorn different blouses were popular. Cutwork was usually done on white fabric, but around Sieradz, a pink and white striped cloth was sometimes used. Eyelet patterns were geometrical until the late 1800s. With the introduction of machine embroidery, designs became more diverse.[8]: 125–132

Sweden

[edit]Hålsöm, or cutwork, was a traditional form of embroidery in Sweden, and used for household linens.[4]: 257

Hand cutwork

[edit]Hand cutworks is the most traditional form of cutwork. Here, areas of the fabric are cut away and stitch is applied to stop the raw edges from fraying.[15]

Laser cutwork

[edit]Laser cutwork allows for more precise and intricate patterns to be created. The laser also has the ability to melt and seal the edges of fabric with the heat of the laser. This helps against fabric fraying during the creation process.[15] Additionally, using a laser for cutwork enables the embroiderer or creator to achieve unique designs such as an 'etched look' by changing the depth of the laser cut into the fabric.

References

[edit]- ^ "What is Cutwork Embroidery? (With picture)". 12 January 2024.

- ^ "A Brief History of Lace | the Lace Guild".

- ^ "Hedebo Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster".

- ^ a b c Gostelow, Mary (1975). A world of embroidery. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-14230-9. OCLC 1413213.

- ^ a b c Betzina, Sandra (2004). More Fabric Savvy: A Quick Resource Guide to Selecting and Sewing Fabric. Taunton Press. ISBN 978-1-56158-662-2.

- ^ Hollen, Norma Rosamond (1979). Textiles. New York: Macmillan. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-02-356130-6.

- ^ "Cutwork | Britannica".

- ^ a b c Kozaczka, Grażyna J. (1987). Old world stitchery for today : Polish eyelet embroidery, cutwork, goldwork, beadwork, drawn thread, and other techniques. Radnor, Pa.: Chilton Books Co. p. 134. ISBN 0-8019-7732-0. OCLC 16130502.

- ^ "Trend alert: Cutwork - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Bath, Virginia Churchill (1979). Needlework in America : history, designs, and techniques. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-50575-7. OCLC 4957595.

- ^ Gostelow, Mary (1983). Embroidery : traditional designs, techniques, and patterns from all over the world. New York: Arco Pub. ISBN 0-668-05905-2. OCLC 9465951.

- ^ Ktori, Maria (2017). "Lefkara Lace: Educational Approaches to ICH in Cyprus". International Journal of Intangible Heritage. 12: 77–88 – via Research Gate.

- ^ Needlework : an illustrated history. Harriet Bridgeman, Elizabeth Drury. New York: Paddington Press. 1978. ISBN 0-448-22066-0. OCLC 3843144.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Walker, Carolyn (1987). The embroidery of Madeira. Kathy Holman (1st ed.). New York: Union Square Press. ISBN 0-941817-00-8. OCLC 15317596.

- ^ a b Richard Sorger; Jenny Udale (1 October 2006). The Fundamentals of Fashion Design. AVA Publishing. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-2-940373-39-0.