Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Embroidery

View on Wikipedia

Embroidery is the art of decorating fabric or other materials using a needle to stitch thread or yarn. It is one of the oldest forms of textile art, with origins dating back thousands of years across various cultures.[1] Common stitches found in early embroidery include the chain stitch, buttonhole or blanket stitch, running stitch, satin stitch, and cross stitch.[2] Modern embroidery continues to utilize traditional techniques, though many contemporary stitches are exclusive to machine embroidery.

Embroidery is commonly used to embellish accessories and garments is usually seen on quilts, clothing, and accessories. In addition to thread, embroidery may incorporate materials such as pearls, beads, quills, and sequins to highlight texture and design. Today, embroidery serves both decorative and functional purposes and is utilized in fashion expression, cultural identity, and custom-made gifts.

A person who is doing embroidery is called an embroiderer. An archaic term is broderer, derived from French broderie for 'embroidery'.[3]

History

[edit]

Origins

[edit]The process used to tailor, patch, mend and reinforce cloth fostered the development of sewing techniques, and the decorative possibilities of sewing led to the art of embroidery.[4] Indeed, the remarkable stability of basic embroidery stitches has been noted:

It is a striking fact that in the development of embroidery ... there are no changes of materials or techniques which can be felt or interpreted as advances from a primitive to a later, more refined stage. On the other hand, we often find in early works a technical accomplishment and high standard of craftsmanship rarely attained in later times.[5]

The art of embroidery has been found worldwide and several early examples have been found. The earliest surviving embroidered cloth comes from Egypt. The Egyptians were skilled at embroidery, using appliqué decorations with leather and beads.[6] Works in China have been dated to the Warring States period (5th–3rd century BC).[7] In a garment from Migration period Sweden, roughly 300–700 AD, the edges of bands of trimming are reinforced with running stitch, back stitch, stem stitch, tailor's buttonhole stitch, and Whip stitch, but it is uncertain whether this work simply reinforced the seams or should be interpreted as decorative embroidery.[8]

Historical applications and techniques

[edit]

Depending on time, location and materials available, embroidery could be the domain of a few experts or a widespread, popular technique. This flexibility led to a variety of works, from the royal to the mundane. Examples of high status items include elaborately embroidered clothing, religious objects, and household items often were seen as a mark of wealth and status.

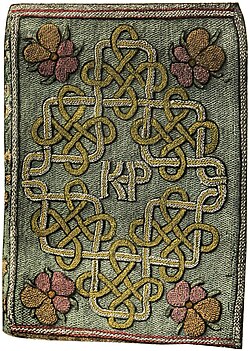

In medieval England, Opus Anglicanum, a technique used by professional workshops and guilds in medieval England,[9] was used to embellish textiles used in church rituals. In 16th century England, some books, usually bibles or other religious texts, had embroidered bindings. The Bodleian Library in Oxford contains one presented to Queen Elizabeth I in 1583. It also owns a copy of The Epistles of Saint Paul, whose cover was reputedly embroidered by the Queen.[10]

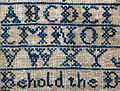

In 18th-century England and its colonies, with the rise of the merchant class and the wider availability of luxury materials, rich embroideries began to appear in a secular context. These embroideries took the form of items displayed in private homes of well-to-do citizens, as opposed to a church or royal setting. Even so, the embroideries themselves may still have had religious themes. Samplers employing fine silks were produced by the daughters of wealthy families. Embroidery was a skill marking a girl's path into womanhood as well as conveying rank and social standing.[11]

Embroidery was an important art and signified social status in the Medieval Islamic world as well. The 17th-century Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi called it the "craft of the two hands". In cities such as Damascus, Cairo and Istanbul, embroidery was visible on handkerchiefs, uniforms, flags, calligraphy, shoes, robes, tunics, horse trappings, slippers, sheaths, pouches, covers, and even on leather belts. Craftsmen embroidered items with gold and silver thread. Embroidery cottage industries, some employing over 800 people, grew to supply these items.[12]

In the 16th century, in the reign of the Mughal Emperor Akbar, his chronicler Abu al-Fazl ibn Mubarak wrote in the famous Ain-i-Akbari:

His majesty [Akbar] pays much attention to various stuffs; hence Irani, Ottoman, and Mongolian articles of wear are in much abundance especially textiles embroidered in the patterns of Nakshi, Saadi, Chikhan, Ari, Zardozi, Wastli, Gota and Kohra. The imperial workshops in the towns of Lahore, Agra, Fatehpur and Ahmedabad turn out many masterpieces of workmanship in fabrics, and the figures and patterns, knots and variety of fashions which now prevail astonish even the most experienced travelers. Taste for fine material has since become general, and the drapery of embroidered fabrics used at feasts surpasses every description.[13]

Conversely, embroidery is also a folk art, using materials that were accessible to nonprofessionals. Examples include Hardanger embroidery from Norway; Merezhka from Ukraine; Mountmellick embroidery from Ireland; Nakshi kantha from Bangladesh and West Bengal; Achachi from Peru; and Brazilian embroidery. Many techniques had a practical use such as Sashiko from Japan, which was used as a way to reinforce clothing.[14][15]

Historically, embroidery was often perceived primarily as a domestic task performed by women, frequently viewed as a leisurely activity rather than recognized as a skilled craft.[16] Women who lacked access to formal education or writing implements often used embroidery to document their lives through stitched narratives, effectively creating personal diaries through textile art, especially when literacy was limited.[17]

In marginalized communities, embroidery has also served as a tool of empowerment and expression. For example, in Inner Mongolia, embroidery initiatives arose in response to economic pressures intensified by climate change, including desertification, allowing women to express themselves and preserve cultural identities through traditional embroidery skills.[18] Embroidery has also preserved the stories of marginalized groups, particularly women of color, whose experiences were historically underrepresented in written records. In South African communities, embroidered "story cloths" have captured and preserved critical perspectives and events otherwise missing from historical narratives.[19]

21st century

[edit]

Since the late 2010s, there has been a growth in the popularity of embroidering by hand. As a result of visual social media such as Pinterest and Instagram, artists can share their work more extensively, which has inspired younger generations to pick up needlework.[20][21]

Contemporary embroidery artists believe hand embroidery has grown in popularity as a result of an increasing need for relaxation and digitally disconnecting practices.[22] Many people are also using embroidery to creatively upcycle and repair clothing, to help counteract over-consumption and fashion industry waste.[23]

Modern canvas work tends to follow symmetrical counted stitching patterns with designs emerging from the repetition of one or just a few similar stitches in a variety of hues. In contrast, many forms of surface embroidery make use of a wide range of stitching patterns in a single piece of work.[24]

Classification

[edit]

Embroidery can be classified according to what degree the design takes into account the nature of the base material and by the relationship of stitch placement to the fabric. The main categories are free or surface embroidery, counted-thread embroidery, and needlepoint or canvas work.[25]

In free or surface embroidery, designs are applied without regard to the weave of the underlying fabric. Examples include crewel and traditional Chinese and Japanese embroidery.

Counted-thread embroidery patterns are created by making stitches over a predetermined number of threads in the foundation fabric. Counted-thread embroidery is more easily worked on an even-weave foundation fabric such as embroidery canvas, aida cloth, or specially woven cotton and linen fabrics. Examples include cross-stitch and some forms of blackwork embroidery.

While similar to counted thread in regards to technique, in canvas work or needlepoint, threads are stitched through a fabric mesh to create a dense pattern that completely covers the foundation fabric.[26] Examples of canvas work include bargello and Berlin wool work.

Embroidery can also be classified by the similarity of its appearance. In drawn thread work and cutwork, the foundation fabric is deformed or cut away to create holes that are then embellished with embroidery, often with thread in the same color as the foundation fabric. When created with white thread on white linen or cotton, this work is collectively referred to as whitework.[27] However, whitework can either be counted or free. Hardanger embroidery is a counted embroidery and the designs are often geometric.[28] Conversely, styles such as Broderie anglaise are similar to free embroidery, with floral or abstract designs that are not dependent on the weave of the fabric.[29]

Traditional hand embroidery around the world

[edit]| Traditional embroidery | Origin | Stitches used | Materials | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aari embroidery | Kashmir and Kutch, Gujarat, India | Chain stitch | Silk thread, fabric, beads or sequins | |

| Art needlework | England |

| ||

| Assisi embroidery | Assisi, Italy | Backstitch, cross stitch, Holbein stitch | Cloth, red thread, silk, stranded perlé cotton |

|

| Balochi needlework | Balochistan, Pakistan | Beads, cloth, shisha, thread |

| |

| Bargello | Florence, Italy | Vertical stitches (e.g. "flame stitch") | Linen or cotton canvas, wool floss or yarn |

|

| Berlin wool work | Berlin, Germany | Cross stitch or tent stitch | Linen or cotton canvas, wool floss or yarn |

|

| Blackwork | England | Backstitch, Holbein stitch, stem stitch | Linen or cotton fabric, black or red silk thread |

|

| Brazilian embroidery | Brazil | Bullion knots, cast-on stitch, drizzle stitch, French knots, featherstitch, fly stitch, stem stitch | Cloth, rayon thread |

|

| Broderie anglaise | Czechia | Buttonhole stitch, overcast stitch, satin stitch | White cloth and thread |

|

| Broderie perse | India | Chintz, thread |

| |

| Bunka shishu | Japan | Punch needle techniques | Rayon or silk thread | |

| Candlewicking | United States | Knotted stitch, satin stitch[30] | Unbleached cotton thread, unbleached muslin |

|

| Chasu | Korea | Chain stitch, couching, leaf stitch, long-and-short stitch, mat stitch, outline stitch, padding stitch, satin stitches, seed stitch |

| |

| Chikan | Lucknow, India | Backstitches, chain stitches, shadow-work | Cloth, white thread |

|

| Colcha embroidery | Southwestern United States | Cotton or linen cloth, wool thread |

| |

| Crewelwork | Great Britain | Chain stitch, couched stitches, knotted stitches, satin stitch, seed stitch, split stitch, stem stitch | Crewel yarn, linen twill |

|

| Goldwork | China | Couching, Holbein stitch, stem stitch | Cloth, metallic thread |

|

| Gota patti | Rajasthan, India |

| ||

| Gu Xiu | Shanghai, China | Silk cloth and thread |

| |

| Hardanger embroidery | Norway | Buttonhole stitch, cable stitch, fly stitch, knotted stitch, picot, running stitch, satin stitch | White thread, white even-weave linen cloth |

|

| Hedebo embroidery | Hedebo, Zealand, Denmark | White linen cloth and thread |

| |

| Kaitag textiles | Kaytagsky District, Dagestan, Russia | Laid-and-couched work | Cotton cloth, silk thread |

|

| Kalaga | Burma |

| ||

| Kantha | Eastern India | Old saris, thread |

| |

| Kasidakari | India | Chain stitch, darning stitch, satin stitch, stem stitch | ||

| Kasuti | Karnataka, India | Cross stitch, double running stitch, running stitch, zigzag running stitch | Cotton thread and cloth |

|

| Khamak | Kandahar, Afghanistan | Satin stitch | Cotton or wool fabric, silk thread | |

| Kuba textiles | The Congo | Embroidery, appliqué, cut-pile embroidery | Raffia cloth and thread |

|

| Kutch embroidery | Kutch, Gujarat, India | Cotton cloth, cotton or silk thread |

| |

| Lambada embroidery | Banjara people |

| ||

| Mountmellick work | Mountmellick, County Laois, Ireland | Knotted stitches, padded stitches | White cotton cloth and thread |

|

| Opus anglicanum | England | Split stitch, surface couching, underside couching[31] | Linen or velvet cloth, metallic thread, silk thread |

|

| Opus teutonicum | Holy Roman Empire | Buttonhole stitch, chain stitch, goblien stitch, pulled work, satin stitch, stem stitch[32] | White linen cloth and thread[32] |

|

| Or nué | Western Europe | Couching | Fabric, metallic thread, silk thread |

|

| Orphrey | ||||

| Needlepoint | Ancient Egypt | Cross stitch, tent stitch, brick stitch | Linen or cotton canvas, wool or silk floss or yarn |

|

| Phool Patti ka Kaam | Uttar Pradesh, India | |||

| Phulkari | Punjab | Darning stitches | Hand-spun cotton cloth, silk floss |

|

| Piteado | Central America | Ixtle or pita thread, leather |

| |

| Quillwork | North America | Beads, cloth, feathers, feather quills, leather, porcupine quills |

| |

| Rasht embroidery | Rasht, Gilan Province, Iran | Chain stitch | Felt, silk thread |

|

| Redwork | United States | Backstitch, outline stitch | Red thread, white cloth | |

| Richelieu | Purportedly from 16th century Italy, revival in 19th century England and France | Buttonhole stitch | White thread, white cloth |

|

| Rushnyk | Slavs[33] | Cross stitch,[34] Holbein stitch, satin stitch[33] | Linen or hemp cloth, thread |

|

| Sashiko | Japan | Running stitch | Indigo-dyed cloth, white or red cotton thread |

|

| Sermeh embroidery | Achaemenid Persia | Termeh cloth, velvet, cotton fabrics, various threads | ||

| Sewed muslin | Scotland | Muslin, thread |

| |

| Shu Xiu | Chengdu, Sichuan, China | Satin, silk thread | ||

| Smocking | England | Cable stitch, honeycomb stitches, knotted stitches, outline stitch, stem stitch, trellis stitch, wave stitch | Any fabric supple enough to be gathered, cotton or silk thread |

|

| Stumpwork | England |

| ||

| Su Xiu | Suzhou, Jiangsu, China | Silk cloth and thread |

| |

| Suzani | Central Asia | Buttonhole stitches, chain stitches, couching, satin stitches | Cotton fabric, silk thread |

|

| Tatreez | Palestine,[35] Syria | Cross stitch | Cotton fabric, silk thread |

|

| Tenango embroidery | Tenango de Doria, Hidalgo, Mexico |

| ||

| Velours du Kasaï | Kasai, the Congo |

| ||

| Vietnamese embroidery | Vietnam |

| ||

| Xiang Xiu | Hunan, China | Silk cloth, black, white, and grey silk thread | ||

| Yue Xiu | Guangdong, China | Silk cloth and thread | ||

| Zardozi | Iran and India | Cloth, metallic thread |

| |

| Zmijanje embroidery | Zmijanje, Bosnia and Herzegovina | Blue thread, white cloth[36] |

|

Materials and tools

[edit]Materials

[edit]

The fabrics and yarns used in traditional embroidery vary from place to place. Wool, linen, and silk have been in use for thousands of years for both fabric and yarn. Today, embroidery thread is manufactured in cotton, rayon, and novelty yarns as well as in traditional wool, linen, and silk. Ribbon embroidery uses narrow ribbon in silk or silk/organza blend ribbon, most commonly to create floral motifs.[37]

Surface embroidery techniques such as chain stitch and couching or laid-work are the most economical of expensive yarns; couching is generally used for goldwork. Canvas work techniques, in which large amounts of yarn are buried on the back of the work, use more materials but provide a sturdier and more substantial finished textile.[38]

Tools

[edit]

A sewing needle is the main stitching tool in embroidery, and comes in various sizes and types. The tips may be sharp or blunt, depending on the type of material the needle needs to be drawn through. Tapestry needles are blunt and larger than a chenille needle which is sharp and shorter than a standard embroidery needle.[39]

In both canvas work and surface embroidery, an embroidery hoop or frame can be used to stretch the material and ensure even stitching tension that prevents pattern distortion.[40] Frames can come in a square or rectangular shape and prevent the canvas from distorting. The two types of frames used are scroll and artist's stretcher bars.[39]

Beeswax is often used to treat thread. It smooths and strengthens threads, especially silk and metallic threads.[39]

Machine embroidery

[edit]

Mass-produced machine embroidery emerged in the early 20th century. As embroidery shifted from personalized craft to mechanical output during the Industrial Revolution, the craft developed into a structured industry centered on large-scale production.[41] The first embroidery machine was the hand embroidery machine, invented in France in 1832 by Josué Heilmann.[42] The next evolutionary step was the schiffli embroidery machine. The latter borrowed from the sewing machine and the Jacquard loom to fully automate its operation. The manufacture of machine-made embroideries in St. Gallen in eastern Switzerland flourished in the latter half of the 19th century.[43] Both St. Gallen, Switzerland and Plauen, Germany were important centers for machine embroidery and embroidery machine development. Many Swiss and Germans immigrated to Hudson county, New Jersey in the early twentieth century and developed a machine embroidery industry there. Shiffli machines have continued to evolve and are still used for industrial scale embroidery.[44]

Contemporary embroidery is stitched with a computerized embroidery machine using patterns digitized with embroidery software. In machine embroidery, different types of "fills" add texture and design to the finished work. Machine embroidery is used to add logos and monograms to business shirts or jackets, gifts, and team apparel as well as to decorate household items for the bed and bath and other linens, draperies, and decorator fabrics that mimic the elaborate hand embroidery of the past.

Machine embroidery is most typically done with rayon thread, although polyester thread can also be used. Cotton thread, on the other hand, is prone to breaking and is avoided.[45]

There has also been a development in free hand machine embroidery, new machines have been designed that allow for the user to create free-motion embroidery which has its place in textile arts, quilting, dressmaking, home furnishings and more. Users can use the embroidery software to digitize the digital embroidery designs. These digitized design are then transferred to the embroidery machine with the help of a flash drive and then the embroidery machine embroiders the selected design onto the fabric.

In literature

[edit]In Greek mythology the goddess Athena is said to have passed down the art of embroidery (along with weaving) to humans, leading to the famed competition between herself and the mortal Arachne.[46]

Gallery

[edit]-

Traditional embroidery in chain stitch on a Kazakh rug, contemporary.

-

Caucasian embroidery

-

English cope, late 15th or early 16th century. Silk velvet embroidered with silk and gold threads, closely laid and couched. Contemporary Art Institute of Chicago textile collection.

-

Extremely fine underlay of St. Gallen Embroidery

-

Traditional Turkish embroidery. Izmir Ethnography Museum, Turkey.

-

Traditional Croatian embroidery.

-

Gold embroidery on a gognots (apron) of a 19th-century Armenian bridal dress from Akhaltsikhe

-

Brightly coloured Korean embroidery.

-

Uzbekistan embroidery on a traditional women's parandja robe.

-

Woman wearing a traditional embroidered Kalash headdress, Pakistan.

-

Bookmark of black fabric with multicolored Bedouin embroidery and tassel of embroidery floss

-

Chain-stitch embroidery from England c. 1775

-

Traditional Bulgarian Floral embroidery from Sofia and Trun.

-

A 1919 painting depicting the Brazilian flag being embroidered by a family.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Fowler, Cynthia (April 25, 2019). The Modern Embroidery Movement (1st ed.). London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. ISBN 978-1350123366.

- ^ "Top 12 Basic Hand Embroidery Stitches". Sarah's Hand Embroidery Tutorials. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ Broderer

- ^ Gillow & Sentance 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Marie Schuette and Sigrid Muller-Christensen, The Art of Embroidery translated by Donald King, Thames and Hudson, 1964, quoted in Netherton & Owen-Crocker 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Needlework. Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia. January 2018.

- ^ Gillow & Sentance 1999, p. 178.

- ^ Coatsworth, Elizabeth: "Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery", in Netherton & Owen-Crocker 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Levey & King 1993, p. 12.

- ^ Harriet Bridgeman; Elizabeth Drury (1978). Needlework : an illustrated history. New York: Paddington Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-448-22066-0. OCLC 3843144.

- ^ Power, Lisa (27 March 2015). "NGV embroidery exhibition: imagine a 12-year-old spending two years on this..." The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ Stone, Caroline (May–June 2007). "The Skill of the Two Hands". Saudi Aramco World. Vol. 58, no. 3. Archived from the original on 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2011-01-21.

- ^ Werner, Louis (July–August 2011). "Mughal Maal". Saudi Aramco World. Vol. 62, no. 4. Archived from the original on 2016-02-22. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- ^ "Handa City Sashiko Program at the Society for Contemporary Craft". Japan-America Society of Pennsylvania. 7 Oct 2016. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Siddle, Kat. "Sashiko". Seamwork Magazine. Colette Media, LLC. Retrieved 2018-01-26.

- ^ Fowler, Cynthia (April 25, 2019). The Modern Embroidery Movement (1st ed.). London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. ISBN 978-1350123366.

- ^ Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (April 1, 1994). Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393035063.

- ^ "Community threads together". chinadailyhk. Retrieved 2024-07-14.

- ^ Merwe, Ria van der (2017). "From a silent past to a spoken future. Black women's voices in the archival process". Archives and Records: The Journal of the Archives and Records Association. 40 (3): 239–258. doi:10.1080/23257962.2017.1388224 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Kouhia, A. (2023). Crafts in the Time of Coronavirus: Pandemic Domestic Crafting in Finland on Instagram’s Covid-Related Craft Posts. M/C Journal, 26(6). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2932

- ^ Mayne, A. (2020). Make/share: Textile making alone together in private and social media spaces. Journal of Arts & Communities, 10(1–2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaac_00008_1

- ^ Elin (2019-06-11). "History of embroidery and its rise in popularity". Charles and Elin. Archived from the original on 2019-07-25. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- ^ "How a traditional craft became a Gen-Z statement". www.bbc.com. 13 April 2024. Retrieved 2025-01-13.

- ^ Reader's Digest 1979, pp. 1–19, 112–117.

- ^ Corbet, Mary (October 3, 2016). "Needlework Terminology: Surface Embroidery". Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Gillow & Sentance 1999, p. 198.

- ^ Reader's Digest 1979, pp. 74–91.

- ^ Yvette Stanton (30 March 2016). Early Style Hardanger. Vetty Creations. ISBN 978-0-9757677-7-1.

- ^ Catherine Amoroso Leslie (1 January 2007). Needlework Through History: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 34, 226, 58. ISBN 978-0-313-33548-8. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "The History and Technique of Candlewicking and Whitework". Needlepointers.com. 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ^ "Technique - Opus Anglicanum". medieval.webcon.net.au. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ^ a b "Technique - Opus Teutonicum". medieval.webcon.net.au. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ^ a b K, Roman (2012-08-07). "FolkCostume&Embroidery: Rushnyk embroidery of southern East Podillia". FolkCostume&Embroidery. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ^ K, Roman (2014-07-01). "FolkCostume&Embroidery: Ukrainian Rose Embroidery". FolkCostume&Embroidery. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ^ Ollman, Leah (October 25, 2017). "Quiet power of embroidery hits eloquently". The Los Angeles Times. p. E3.

- ^ "UNESCO - Zmijanje embroidery". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ^ van Niekerk 2006.

- ^ Reader's Digest 1979, pp. 112–115.

- ^ a b c "Glossary of Embroidery Terms". Embroiderers' Guild of America. Retrieved 28 April 2025.

- ^ "Materials Required for Hand Embroidery". Sarah's Hand Embroidery Tutorials. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ Adamson, Glenn (Jan 10, 2019). The Invention of Craft (1st ed.). London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. ISBN 978-0857850645.

- ^ Willem. "Hand Embroidery Machine". trc-leiden.nl. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- ^ Röllin, Peter. Stickerei-Zeit, Kultur und Kunst in St. Gallen 1870–1930. VGS Verlagsgemeinschaft, St. Gallen 1989, ISBN 3-7291-1052-7 (in German)

- ^ Schneider, Coleman (1968). Machine Made Embroideries. Globe Lithographing Company.

- ^ "Choosing Machine-Embroidery Threads". Threads Magazine. The Taunton Press, Inc. 2008-11-02. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ Synge, Lanto (2001). Art of Embroidery: History of Style and Technique. Woodbridge, England: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 32. ISBN 9781851493593.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gillow, John; Sentance, Bryan (1999). World Textiles. Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown. ISBN 0-8212-2621-5.

- Levey, S. M.; King, D. (1993). The Victoria and Albert Museum's Textile Collection Vol. 3: Embroidery in Britain from 1200 to 1750. Victoria and Albert Museum. ISBN 1-85177-126-3.

- Netherton, Robin; Owen-Crocker, Gale R., eds. (2005). Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 1. Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-123-6.

- Complete Guide to Needlework. Reader's Digest. 1979. ISBN 0-89577-059-8.

- van Niekerk, Di (2006). A Perfect World in Ribbon Embroidery and Stumpwork. Search Press. ISBN 1-84448-231-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Berman, Pat (2000). "Berlin Work". American Needlepoint Guild. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- Caulfeild, S.F.A.; B.C. Saward (1885). The Dictionary of Needlework.

- Crummy, Andrew (2010). The Prestonpans Tapestry 1745. Burke's Peerage & Gentry, for Battle of Prestonpans (1745) Heritage Trust.

- Embroiderers' Guild Practical Study Group (1984). Needlework School. QED Publishers. ISBN 0-89009-785-2.

- Koll, Juby Aleyas (2019). Sarah's Hand Embroidery Tutorials.

- Lemon, Jane (2004). Metal Thread Embroidery. Sterling. ISBN 0-7134-8926-X.

- Vogelsang, Gillian; Vogelsang, Willem, eds. (2015). TRC Needles. The TRC Digital Encyclopaedia of Decorative Needlework. Leiden, The Netherlands: Textile Research Centre.

- Wilson, David M. (1985). The Bayeux Tapestry. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-25122-3.

External links

[edit] Media related to Embroidery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Embroidery at Wikimedia Commons

- The History of Embroidery

Embroidery

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Prehistoric Evidence

The origins of embroidery trace to prehistoric times, when early humans developed sewing techniques that enabled both functional garment construction and decorative embellishment. Direct evidence remains sparse owing to the perishable nature of textiles, with most insights derived from durable tools such as bone and antler needles, awls, and indirect traces like shell or tooth attachments on clothing fragments.[11][12] Eyed needles, essential for precise stitching, first appear in the archaeological record during the Upper Paleolithic, around 40,000 years ago, at Eurasian sites including those in Siberia and Europe. These implements, crafted from animal bone or ivory, facilitated tailored clothing and the potential incorporation of decorative motifs using threads from sinew, plant fibers, or animal hair. Their widespread distribution indicates sewing was not a rare innovation but a standard technology for personal adornment amid glacial climates.[12][13] One of the earliest documented instances of prehistoric embroidery comes from the Late Mesolithic site of Vlasac in Serbia, dated to approximately 6500 BCE, where human burials yielded garment fragments adorned with sewn-on perforated carp teeth, deer canines, and snail shells. These attachments, secured via small perforations and likely organic threads, represent deliberate decorative enhancement rather than mere utility, marking an early form of appliquéd or beaded embroidery.[14][15] Such finds underscore that embroidery emerged as an extension of sewing for survival—initially for fur insulation—but evolved to convey status or identity through ornamentation, using locally sourced materials. In the absence of preserved fabrics, these artifacts provide the primary empirical basis for inferring embroidery's prehistoric roots, predating metallurgical or written records by millennia.[16]Ancient Civilizations

In ancient Egypt, embroidered textiles appear among the earliest preserved examples from organized civilizations, with fragments of linen garments featuring stitched motifs dating to approximately 3000 BC recovered from royal and elite tombs.[4] These artifacts, often consisting of hem panels and borders with geometric or simple linear patterns executed in flax thread, demonstrate early technical proficiency in needlework on plant-based fabrics.[17] More elaborate pieces, such as robes adorned with beads, gold threads, and embroidered designs, were unearthed in Tutankhamun's tomb (c. 1323 BC), excavated in 1922, highlighting embroidery's role in funerary and ceremonial contexts for high-status individuals.[18] In Mesopotamia and surrounding Near Eastern cultures, including Babylonian and Assyrian societies (c. 2000–500 BC), embroidery is inferred from artistic depictions and textile remnants showing decorated wool and linen garments, though direct surviving fragments are rare due to environmental degradation.[19] Wealthy individuals wore tunics with intricate stitched embellishments, often using tassels and dyed threads for status differentiation, as evidenced by sculptural reliefs and cuneiform references to skilled textile workers.[20] Similarly, ancient Syrian and early Greek textiles incorporated embroidery on fine linens, supported by bone needles found in tombs from the 2nd millennium BC, indicating localized production for elite apparel and ritual items.[19] Chinese embroidery originated in the Neolithic period (c. 5000–2000 BC), coinciding with the development of sericulture, where simple stitched patterns on silk and hemp fabrics served decorative and symbolic purposes.[21] Archaeological finds from Xinjiang sites reveal early silk threads used in appliqué-like techniques, evolving into more complex motifs by the Warring States period (475–221 BC).[22] The practice expanded significantly during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), with embroidered silk panels featuring floral, animal, and auspicious symbols produced for imperial robes and burial shrouds, reflecting advancements in thread quality and stitch variety.[23] In the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300–1300 BC), evidence of embroidery emerges from terracotta needles and spindle whorls at sites like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, alongside impressions of stitched cotton and wool textiles suggesting decorative surface work. These indicate early regional traditions of embellishing garments with geometric and talismanic patterns, though perishable materials limit direct preservation, with inferences drawn from tool assemblages and comparative Indian subcontinental heirlooms.[24] Across these civilizations, embroidery's development was constrained by material availability and climate, favoring durable threads like flax, wool, and silk, and primarily serving utilitarian enhancement for elites rather than mass production.[25]Medieval and Renaissance Developments

The Bayeux Tapestry, created in the late 11th century around 1070-1080, exemplifies early medieval embroidery techniques in Europe, depicting the Norman Conquest of England through wool threads worked in laid and couched stitches on linen panels measuring approximately 70 meters long and 50 centimeters wide.[26] This monumental work, likely produced in Normandy or England by skilled embroiderers including women, utilized eight colors of crewel wool to narrate historical events, highlighting the narrative potential of embroidery for commemorative purposes.[27] During the High Middle Ages, particularly from the 12th to 14th centuries, English embroidery known as Opus Anglicanum achieved prominence, renowned for its intricate ecclesiastical vestments exported across Europe to churches and cathedrals.[28] These pieces featured gold and silver threads, colored silks, and freshwater pearls in techniques such as split stitch, underside couching, and raised work, crafted by professional workshops of both men and women who worked meticulously under natural light.[29] The craft's prestige stemmed from its technical complexity and material opulence, supporting the Church's liturgical needs and reflecting socioeconomic organization where embroiderers operated as specialized artisans.[30] In the Renaissance period, from the 14th century onward, embroidery evolved with Italian innovations in Florence, incorporating goldwork like or nué—where gold threads were laid over a painted base and couched selectively—and spreading to northern Europe by the 15th and 16th centuries as a marker of elite status.[31] Techniques such as blackwork, using fine linen and silk in counted thread patterns influenced by Islamic motifs via trade routes, gained favor in England during the Elizabethan era (1558–1603), appearing on royal garments and portrait collars.[6] Raised embroidery, or stumpwork, emerged prominently in the 17th century as an extension of Renaissance developments, creating three-dimensional effects with padding and detached elements for decorative items like caskets and mirrors, shifting focus from purely religious to secular and personal applications.[6] This era's advancements were driven by increased silk imports and professional guilds, enhancing embroidery's role in fashion and household arts across courts.[32]Industrial Era Transformations

The Industrial Revolution, beginning in Britain around 1760 and spreading to continental Europe by the early 19th century, profoundly altered embroidery from an artisanal craft reliant on manual labor to a mechanized process enabling mass production. Steam-powered machinery and advances in textile engineering reduced production times and costs, shifting embroidery from elite decorative work to components of affordable consumer goods like clothing and household linens. This transformation democratized access to ornamented fabrics but diminished the uniqueness of hand-stitched pieces, as machine uniformity prioritized efficiency over individual artistry.[33][34] A pivotal early development was the 1828 invention of the hand embroidery machine by French inventor Josué Heilmann in Mulhouse, which used multiple needles to mimic hand stitching on a frame that operators manually repositioned. This semi-automatic device marked the transition from fully manual methods, allowing faster replication of simple patterns on fabrics like muslin and lace, though it still required skilled oversight. By the mid-19th century, refinements integrated elements of sewing machine technology, patented by Elias Howe in 1846 and commercialized by Isaac Singer from 1851, which facilitated basic embroidered trims on garments produced in factories.[35][36] The true breakthrough for complex embroidery came with the Schiffli machine, devised in 1863 by Swiss inventor Isaak Gröbli in St. Gallen, a region that became a global hub for mechanized lace and embroidery production. Employing a shuttle system akin to boat sails ("Schiffli" meaning "little boat" in Swiss German), it automated stitching with continuous thread and multiple needles, producing intricate designs on large-scale fabrics without manual frame adjustment. By 1898, Gröbli's son Joseph introduced an automatic version incorporating Jacquard mechanisms—originally developed for looms in 1804 by Joseph Marie Jacquard—to control patterns via punched cards, enabling precise replication of elaborate motifs at industrial speeds. This innovation supported the export of Swiss embroidered goods, with St. Gallen factories outputting millions of meters annually by the early 20th century, fueling trade in collars, handkerchiefs, and trimmings.[37][38][39] These machines reduced labor intensity, with one Schiffli unit capable of work equivalent to dozens of hand embroiderers, but they also displaced traditional artisans, particularly women in cottage industries, as factories centralized production. Empirical records from Swiss textile archives indicate output surges: pre-1860s hand embroidery yielded about 1-2 square meters per worker per day, versus 10-20 times that volume post-Schiffli adoption. While hand embroidery persisted in luxury markets and revival movements like the Arts and Crafts response to industrialization, machine methods dominated commercial applications, standardizing designs and integrating embroidery into ready-to-wear apparel by the late 19th century.[40][35]20th and 21st Century Evolution

The early 20th century witnessed a continuation of the Arts and Crafts movement's emphasis on hand embroidery as a counter to industrialization, promoting techniques such as crewelwork and goldwork through workshops and pattern books that revived medieval styles using natural dyes and hand-spun yarns.[6] This period also saw advancements in machine embroidery, including the invention of the first multi-head embroidery machine in 1911, which enabled simultaneous production on multiple garments, facilitating mass output for commercial applications.[36] In haute couture, ateliers like Maison Lesage, under François Lesage from 1949, supplied intricate hand-embroidered elements to designers, preserving artisanal methods amid growing mechanization.[41] Mid-century developments included the rise of embroidery as a domestic hobby, with techniques like needlepoint and Berlin wool work popularized through mail-order patterns and kits, reflecting post-World War II consumer culture.[34] Feminist movements in the 1960s and 1970s repurposed embroidery for protest and personal expression, challenging its association with domesticity by incorporating it into fine art and political banners.[42] Technological progress accelerated with the introduction of computerized embroidery machines in the late 1970s, such as Brother's 1979 model, which automated stitch patterns via punch cards and later digital programming, democratizing complex designs for home and industrial use. In the 21st century, digital embroidery software and multi-needle home machines have integrated computer-aided design, allowing precise customization and rapid prototyping for fashion and apparel.[43] Social media platforms have fueled a revival of hand embroidery, promoting tutorials, contemporary patterns, and artisanal sales, while sustainability drives the use of recycled threads and eco-friendly dyes in both traditional and machine techniques.[44] Fusion styles blending global motifs with modern aesthetics appear in haute couture runways, as seen in collections from houses like Dior and Chloé in 2025, underscoring embroidery's enduring role in high fashion.[45]Techniques and Classification

Fundamental Stitches and Methods

Fundamental stitches in hand embroidery serve as the foundational techniques for creating lines, shapes, fills, and textures on fabric. These stitches, developed over centuries, include outline stitches for defining edges, filling stitches for covering areas solidly, and decorative knots for accents. Reputable institutions such as the Royal School of Needlework identify core stitches like back stitch and French knots as essential across practical and ornamental applications.[46][47] The running stitch, one of the simplest forms, involves passing the needle in and out of the fabric at regular intervals to form a dashed line, commonly used for temporary basting or basic outlining.[48] The back stitch creates a continuous solid line by working from right to left, inserting the needle behind the previous stitch, providing durability for seams and precise outlines.[49] Stem stitch, similar but twisted, produces a rope-like effect ideal for curved stems and branches, achieved by keeping the thread below the needle on emergence.[50] Chain stitch forms interconnected loops resembling links, worked by drawing the needle through a loop formed by the previous stitch, suitable for bold lines and fillings in historical textiles.[51] Split stitch, an ancient technique evidenced in medieval embroidery, splits emerging threads to create a textured line, often used for outlines before filling.[29] Satin stitch fills shapes with parallel straight stitches laid side by side without twisting, requiring even tension to avoid puckering and commonly applied in floral motifs.[52][53] French knots add dimensional dots or centers by wrapping thread around the needle tip before inserting, with the number of wraps determining size, as seen in decorative patterns from various traditions.[54][53] Blanket stitch, also known as buttonhole stitch, secures edges by encircling parallel stitches around a line, historically used for finishing appliqués and hems.[55] Cross stitch, a counted method forming X shapes over even-weave fabric, builds geometric patterns by completing half-stitches in rows.[56] Methods of application divide into surface embroidery, where stitches are placed freely on the fabric surface guided by a drawn design, and counted thread embroidery, which relies on the precise grid of fabric weaves for uniform results, as in cross stitch or blackwork.[57] Surface methods emphasize artistic interpretation, while counted techniques ensure reproducibility, with tools like hoops maintaining fabric tautness during work.[58] Design transfer via tracing, pricking, or pouncing precedes stitching, allowing adaptation to different fabrics and threads.[29] These stitches and methods underpin diverse embroidery styles, from utilitarian to ornamental.[47]Hand Embroidery Styles

Hand embroidery styles are categorized primarily into counted-thread, surface or freestyle, and whitework techniques, each defined by distinct methods of stitch placement and material use. Counted-thread embroidery relies on even-weave fabrics where stitches are counted from a grid pattern to create precise, geometric designs, often using silk, cotton, or linen threads.[8] Surface embroidery, by contrast, follows a pre-drawn outline on the fabric, employing a range of stitches for pictorial or decorative effects, typically with wool or silk yarns. Whitework emphasizes texture through manipulation of white threads on white fabric, incorporating elements like drawn threads, cutwork, and padding to produce open, lacy patterns.[8] Cross-stitch, a prominent counted-thread style, forms X-shaped stitches on even-weave fabric to produce tiled, raster-like patterns, with origins traceable to silk floss embroidery on cotton from the 13th century in Lebanon's Qadisha Valley and flourishing during China's Tang Dynasty (618–906 AD).[59] This technique spread westward via trade routes, enabling detailed motifs such as florals or figures, and by the late 1500s, printed patterns facilitated its widespread adoption in Europe.[60] Blackwork, another counted-thread variant, uses fine black silk thread—though colors vary—on linen or cotton, featuring double-running or Holbein stitches for reversible, geometric fillings and outlines; its roots lie in 14th–15th century Islamic embroideries introduced to Spain by the Moors around 711 CE, gaining popularity in 16th-century Tudor England.[61] The style's subtle shading and interlocking patterns adorned clothing and household linens, emphasizing precision over bold color.[62] Crewelwork represents a surface embroidery tradition using wool yarns ("crewel" deriving from an old term for wool) on linen twill, with stems, satin, and French knots to depict Jacobean-era floral and fauna motifs; documented from the 17th century in England but with precedents in the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, it revived in the 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement for bed hangings and upholstery.[63] The technique's durability stems from wool's resilience, allowing dense, textured coverage without rigid counting.[64] Whitework encompasses techniques like Hardanger, a Norwegian counted and cutwork method on even-weave linen, involving satin stitches over counted grids followed by cutting and withdrawing threads to form open geometric voids filled with needleweaving or buttonhole bars for a lacy effect; practiced traditionally since the 17th century in Hardangerfjord regions for ceremonial garments.[65] Other whitework variants include pulled-thread work, where tension distends fabric threads to create transparency, and broderie anglaise, featuring eyelets and scalloped edges via cutting and overcasting.[66] Goldwork employs metal threads—gold, silver, or imitations—couched onto fabric rather than sewn through, using fine needles to lay passing threads parallel and secure them with stitches, often over felt padding for raised elements like or nué shading; this labor-intensive method, prized for light-reflective qualities, dates to ancient ecclesiastical vestments and persists in ceremonial items.[67] Techniques such as chipping (applying sequin-like metal pieces) and s-ing (twisting wires) enhance dimensionality, requiring specialized tools to avoid thread damage.[68]Machine and Digital Techniques

Machine embroidery emerged in the early 19th century as a mechanized alternative to hand stitching, enabling faster production of decorative patterns on fabric. The first hand-operated embroidery machine was invented by French engineer Josué Heilmann in 1828 near Mulhouse, France; this device used a single needle and pantograph guidance system, allowing an operator to trace designs manually while the machine emulated basic stitches, potentially matching the output of multiple hand embroiderers.[69][70] Subsequent advancements shifted toward powered mechanisms. In 1863, Swiss engineers developed the Schiffli machine, named after its wing-like shuttle derived from loom technology, which automated chain stitching for larger-scale production and reduced reliance on manual guidance.[71] Multi-head machines appeared around 1911, facilitating simultaneous embroidery on multiple items for industrial efficiency, particularly in apparel and textile manufacturing.[71] These early machines primarily handled simple satin, chain, and running stitches, with limitations in complex fills due to mechanical constraints. Digital techniques revolutionized embroidery in the late 20th century through computer control, integrating CAD/CAM processes to generate precise stitch files from vector artwork. By the 1980s, electronic controls enabled programmable needle movements, with companies like Tajima introducing multi-head systems featuring servo motors for consistent tension and speed up to 1,200 stitches per minute.[36] Modern computerized machines, often classified as CNC embroidery systems, use digitized files (e.g., .DST or .PES formats) to execute designs automatically, incorporating features like automatic thread trimming, color changes, and hoop positioning.[72] Key digital processes include embroidery digitizing, where software algorithms convert graphical inputs into stitch paths, accounting for fabric distortion, thread density (typically 0.4–0.6 mm spacing for fills), and stitch types such as tatami for area coverage or running stitches for outlines.[73] Advanced techniques employ 3D simulation to preview results, pull compensation to adjust for fabric stretch, and underlay stitching for stability on stretchy materials.[74] Home and commercial machines now support USB or wireless file transfer, with multi-needle models reducing setup time for designs using 6–15 colors.[75] These methods have expanded applications to technical textiles, such as reflective or conductive threads for wearable electronics, though quality depends on software precision and machine calibration.[76]Regional and Cultural Traditions

Asian Traditions

Embroidery traditions in Asia originated with the domestication of silkworms in China approximately 5,000 years ago, enabling the production of silk threads for decorative stitching on fabrics.[77] Early evidence from the Neolithic period includes simple embroidery found in the Xinjiang region, where archaeological sites reveal stitched patterns on textiles dating back to around 3000 BCE.[22] By the Shang Dynasty (circa 1600–1046 BCE), more complex embroidered artifacts appeared, primarily adorning clothing, banners, and ceremonial items using techniques like satin stitch and chain stitch on silk.[78] Chinese embroidery evolved into four major regional schools—Suzhou (emphasizing fine silk and double-sided work), Hunan (bold colors and cross-stitch), Guangdong (realistic floral motifs), and Sichuan (satin stitch on coarser fabrics)—each reflecting local materials and cultural motifs by the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912 CE).[79] In Japan, embroidery techniques arrived from China via Korea in the 6th century CE, initially applied to Buddhist textiles and court garments during the Heian period (794–1185 CE).[80] Known as nihon shishu, it featured minimalist designs with gold and silk threads, often depicting nature and imperial symbols on kimono and Noh theater costumes, passed down through guilds for over 1,600 years.[81] Sashiko, a running stitch variant for reinforcement, emerged in rural areas during the Edo period (1603–1868 CE) to mend indigo-dyed cotton, later incorporating geometric patterns for aesthetic durability.[82] Korean embroidery, influenced by Chinese styles during the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392 CE), flourished in silk and satin for bojagi wrapping cloths and official insignia from the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897 CE), using counted thread methods on hanbok garments and folding screens.[83] Indian embroidery traces to at least the 12th century CE with aari work, a chain stitch using a hooked needle, developed by leather-working communities in regions like Gujarat for adorning footwear and later saris.[84] Mughal influence from the 16th century introduced zardozi, involving gold and silver wires couched onto velvet for royal attire, peaking in opulent floral and paisley designs.[85] Regional styles include phulkari from Punjab (15th century onward), featuring darning stitches on khaddar cloth for bridal veils with unworked background, and kantha from Bengal, a running stitch repurposing saris into quilts with narrative motifs dating to pre-Vedic times before 1500 BCE.[86] In Southeast Asia, Hmong communities practiced paj ntaub embroidery from at least the 19th century, appliquéing and cross-stitching symbolic motifs like elephants and crosses onto hemp skirts to denote clan identity and stories.[87] Peranakan nyonya embroidery in Malaysia and Singapore, from the 19th century, layered beadwork and satin stitches on batik sarongs for ceremonial blouses.[88] These traditions emphasize functional decoration tied to social rituals, with silk, cotton, and metal threads enabling durable, symbolic expressions across diverse climates and economies.[89]European Traditions

The Bayeux Tapestry, completed around 1070 in Normandy, exemplifies early European embroidery through its use of wool threads in laid and couched stitches on linen, depicting the Norman Conquest in 68 scenes spanning 70 meters.[26] This monumental work, likely produced by skilled embroiderers under ecclesiastical patronage, highlights the technique's role in historical narration and its reliance on natural dyes from plants like woad and madder for colorfastness.[26] In medieval England, Opus Anglicanum emerged as a pinnacle of embroidery artistry from approximately 1200 to 1350, featuring fine silk split-stitch outlines filled with gold and silver threads for ecclesiastical vestments and secular hangings exported across Europe.[90] Workshops in London and other centers employed professional embroiderers, often women, producing pieces admired for their naturalistic figures and underlay padding techniques that created raised effects, as documented in contemporary inventories sent to papal courts.[91] The style's reputation stemmed from its technical innovation, including underside couching to secure metal threads without surface knots, reflecting empirical advancements in thread management for durability.[90] By the 17th century, British crewelwork flourished, particularly in Jacobean styles using wool yarns on twill linens to depict floral and faunal motifs for bed hangings and upholstery, peaking during the Stuart period with influences from imported Persian designs via trade routes.[8] Techniques such as chain, stem, and satin stitches allowed for textured landscapes, with surviving examples from 1696 demonstrating the craft's adaptation to domestic interiors amid growing colonial wool supplies.[8] In Scandinavia, Hardanger embroidery, originating in Norway's Hardanger region by the 17th century, developed as a form of whitework on evenweave linen using counted thread techniques like kloster blocks—voided satin stitch squares—and buttonhole fillings for geometric patterns symbolizing prosperity.[92] Flourishing between 1650 and 1850, it incorporated Renaissance influences from Italian lace via Persian routes, evolving into intricate edge treatments for traditional costumes and linens, with pearl cotton threads enhancing openness and light play.[93] English sampler traditions, dating to the late 16th century, served educational purposes, teaching girls alphabets, motifs, and stitches like cross and eyelet on linen, with over 700 examples in collections spanning to the 20th century, evidencing skill transmission amid rising literacy demands.[94] By 1826, samplers like Alice Maywood's incorporated pictorial scenes and moral inscriptions, reflecting bourgeois aspirations and the craft's shift from utility to accomplishment display.[94] These practices underscore embroidery's causal role in preserving techniques through empirical repetition, undeterred by guild controls that historically restricted professional access.Traditions in Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas

In Africa, embroidery traditions vary by region and culture, often serving decorative and symbolic purposes on clothing and textiles. Among the Hausa people of northern Nigeria, embroidery on robes and garments dates back to at least the 14th century, initially practiced primarily by men using techniques that incorporate intricate patterns symbolizing cultural identity and Islamic influences.[95] In West Africa, both men and women embroider cloths with heritage symbols, as seen in traditions from Mali, Ghana, and Nigeria, where stitches convey pride and social status.[96] Further east, Ethiopian embroidery integrates with weaving in traditional garments, persisting through historical upheavals like wars and religious changes since at least the early 20th century in documented examples.[97] Middle Eastern embroidery features ancient roots and regional motifs tied to identity and landscape. Palestinian tatreez, derived from Aramaic roots meaning "to embroider," originated around 3,000 years ago in Canaan and became widespread across the region by the 9th century, with women using cross-stitch and other techniques on thobes to depict floral, geometric, and protective symbols inspired by local flora and architecture.[98][99] In Saudi Arabia's Najd desert tribes, embroidery decorates traditional dresses with patterns varying by tribe, employing methods like appliqué and chain stitch that highlight regional distinctions in Hejaz and other areas.[100] The practice in the broader Arab world traces to early examples, such as those from Tutankhamun's tomb in Egypt around 1323 BCE, evolving into communal women's crafts that preserve cultural narratives.[101] Embroidery traditions in the Americas blend indigenous techniques with post-contact influences, particularly after European arrival introduced metal needles and threads. Among Mexico's Otomi people in the central altiplano, embroidery features vibrant, whimsical patterns of animals and plants on tenangos, a style practiced for generations by women using chain and satin stitches that can take weeks to complete.[102] In the Andean region, pre-Columbian cultures like the Inca valued textiles highly—sometimes more than gold—but true embroidery emerged more prominently in colonial eras, with techniques adapting to include European stitches on wool and cotton.[103] North American indigenous groups, such as those in the Eastern Woodlands, initially used porcupine quills and moose hair for decorative sewing before 1600, transitioning to embroidery with trade beads and threads by the 18th century, as evidenced in surviving garments.[104] In the American Southwest, colcha embroidery, originating in 18th-century Spanish colonial New Mexico, combines floral motifs with long-and-short stitch on wool, often by Hispanic women adapting indigenous wool weaving traditions.[105]Indigenous and Other Global Variations

Indigenous embroidery practices worldwide frequently incorporate locally sourced materials and motifs reflective of environmental and spiritual significance, predating colonial influences in many cases. Techniques such as quillwork among North American tribes involved softening porcupine quills with moisture before flattening and sewing them onto hides or birchbark, creating durable decorative patterns for clothing, bags, and ceremonial items; this method was prevalent among Woodland and Plains peoples from at least the 15th century onward, as evidenced by archaeological finds.[106] Moose hair embroidery, practiced by Northeast Woodlands Indigenous groups like the Mi'kmaq and Huron, utilized dyed moose or porcupine hair wrapped around threads in a false embroidery style—essentially a wrapped weaving—to adorn straps, pouches, and footwear, often featuring floral or geometric designs symbolizing clan identities.[107] In the Arctic regions, Inuit communities traditionally enhanced caribou or sealskin garments with appliqué insets of contrasting furs and sinew stitching for decoration, evolving post-19th-century trade into thread-based embroidery on cloth items like parkas and household textiles; these often displayed bold, simplified motifs of animals and landscapes, with women specializing in the craft for both utility and cultural continuity.[108] Further south in Mesoamerica, the Otomi people of central Mexico employ a distinctive style characterized by dense chain-stitch fillings in vibrant colors, depicting abstracted native flora, fauna, and geometric forms inspired by prehispanic cosmology; this technique, using cotton threads on cotton or wool fabrics, remains a vital economic and identity-preserving practice among Otomi women as of the 21st century.[102] In the American Southwest, colcha embroidery emerged in the 18th century as a fusion of Spanish colonial satin stitch with Indigenous Pueblo motifs, featuring large-scale floral, avian, and landscape scenes on wool blankets or coverlets; while introduced by Hispanic settlers, many examples incorporate Native American symbolic elements like corn maidens or sacred animals, reflecting cultural syncretism in New Mexico and Colorado regions.[109] Andean Indigenous groups in Peru have long integrated embroidery using alpaca wool or cotton threads into textiles, applying cross-stitch and appliqué to create narrative scenes of daily life and mythology on garments and shawls; these practices, rooted in pre-Inca traditions, continue in highland communities where natural dyes from cochineal insects and plants yield enduring colors.[110] Such variations highlight embroidery's role in Indigenous resilience, adapting pre-contact methods like quilling or fiber wrapping to threaded forms while preserving motifs tied to ancestral knowledge.Materials and Equipment

Threads, Fabrics, and Supplies

Embroidery threads derive from natural fibers including cotton, which yields a matte, absorbent surface ideal for surface stitches and cross-stitch due to its strength and ease of splitting into strands; silk, prized for its sheen, smoothness, and historical use in delicate shading techniques dating back to ancient China around 4000 BCE; wool, offering texture and warmth for crewelwork on linen or cotton grounds since the 17th century; and linen, providing durability but prone to fraying in finer gauges.[111][112][113] Synthetic alternatives like polyester exhibit superior tensile strength, resistance to shrinking and fading under exposure, and cost-effectiveness, making them prevalent in machine embroidery since the mid-20th century, while rayon mimics silk's luster but at lower durability.[114][115] Fabrics for embroidery must feature stable weaves to support needle penetration without distortion; even-weave cottons, such as quilting fabric at 150-200 threads per inch, allow precise counting for techniques like counted-thread work, while linen provides a crisp texture suited to historical European styles but requires stabilization to prevent puckering.[116][117] Silk fabrics, though luxurious and sheen-enhancing for goldwork, demand careful handling due to slippage, with evidence of their use in embroidered textiles from 4th-century BCE Chinese artifacts.[118] Avoid knits or heavily stretched synthetics, as they shift under tension, compromising stitch integrity; Aida cloth, a rigid open-weave cotton or blend introduced in the 19th century, facilitates beginners' cross-stitch by visibly gridding holes up to 14 counts per inch.[119]| Thread Material | Key Properties | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Cotton | Matte finish, splittable strands, strong yet flexible | Surface embroidery, cross-stitch[113] |

| Silk | Lustrous sheen, smooth glide, fine for shading | Historical fine work, silk shading[111] |

| Wool | Textured, insulating, bulky | Crewel embroidery on twill[112] |

| Polyester | Durable, colorfast, shrink-resistant | Machine stitching, outdoor applications[114] |

_LACMA_AC1994.131.1.jpg/250px-Kantha_(Quilt)_LACMA_AC1994.131.1.jpg)

_LACMA_AC1994.131.1.jpg/2000px-Kantha_(Quilt)_LACMA_AC1994.131.1.jpg)