Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

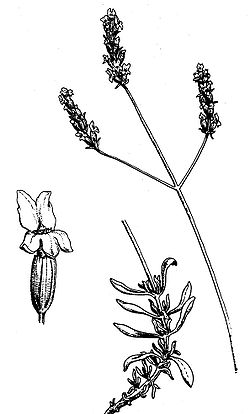

Lavandula latifolia

View on Wikipedia

| Lavandula latifolia Spike lavender | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Lamiaceae |

| Genus: | Lavandula |

| Species: | L. latifolia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lavandula latifolia | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Lavandula latifolia, known as broadleaved lavender,[3] spike lavender, aspic lavender or Portuguese lavender, is a flowering plant in the family Lamiaceae, native to the western Mediterranean region, from central Portugal to northern Italy (Liguria) through Spain and southern France. Hybridization can occur in the wild with English lavender (Lavandula angustifolia).

The scent of Lavandula latifolia is stronger, with more camphor, and more pungent than Lavandula angustifolia scent. For this reason the two varieties are grown in separate fields.

Description

[edit]Lavandula latifolia is a strongly aromatic shrub growing to 30–80 cm tall. The leaves are evergreen, 3–6 cm long and 5–8 mm broad.

The flowers are pale lilac, produced on spikes 2–5 cm long at the top of slender, leafless stems 20–50 cm long. Flowers from June to September, depending on weather.

The fruit is a nut, indehiscent, monosperm of hardened pericarp. It consists of 4 small nuts which often remain locked inside the calyx tube. Grows from 0 to 1,700 m amsl.[4]

Etymology

[edit]The species name latifolia is Latin for "broadleaf". The genus name Lavandula simply means lavender.

Chemical composition

[edit]Uses

[edit]Lavandula latifolia can be used in aromatherapy.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Khela, S. (2013). "Lavandula latifolia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013 e.T203245A2762556. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T203245A2762556.en. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Sinonimia en Tela Botánica". Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ^ NRCS. "Lavandula latifolia". PLANTS Database. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Bolòs and Vigo Flora dels Països Catalans Barcelona 1990

- ^ a b c d e f g h Salido, Sofía; Altarejos, Joaquín; Nogueras, Manuel; Sánchez, Adolfo; Luque, Pascual (May 2004). "Chemical Composition and Seasonal Variations of Spike Lavender Oil from Southern Spain". Journal of Essential Oil Research. 16 (3): 206–210. doi:10.1080/10412905.2004.9698698.

- ^ "Lavandula latifolia Spike Lavender, Broadleaved lavender PFAF Plant Database". pfaf.org. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

Bibliography

[edit]- Blumenthal M, Goldberg A, Brinckmann J. Herbal Medicine, Expanded Commission E Monographs. Integrative Medicine Communications, Newton. First Edition, 2000.

- Grases F, Melero G, Costa-Bauza A et al. Urolithiasis and phytotherapy. Int Urol Nephrol 1994; 26(5): 507–11.

- Paris RR, Moyse H. Matière Médicale. Masson & Cia., Paris; 1971. Tome .

- PDR for Herbal Medicines. Medical Economics Company, Montvale. Second Edition, 2000.

Lavandula latifolia

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and nomenclature

Etymology

The genus name Lavandula derives from the Latin verb lavare, meaning "to wash," alluding to the historical use of lavender plants in bathing, perfumery, and cleaning due to their fragrant properties.[6] This etymological connection reflects ancient Roman practices where lavender was employed to scent water and linens.[7] The specific epithet latifolia is composed of two Latin roots: latus, meaning "broad" or "wide," and folium, meaning "leaf," emphasizing the species' characteristic broader foliage in contrast to the narrower leaves of related lavender species like Lavandula angustifolia.[8] This descriptor highlights a key morphological distinction that aids in taxonomic identification within the genus.[9] The binomial Lavandula latifolia was formally established by the German botanist Friedrich Kasimir Medikus in 1784, in Botanische Beobachtungen des Jahres 1783, building on the genus framework created by Carl Linnaeus in his 1753 Species Plantarum, where Linnaeus had described related species under Lavandula but did not include this one.[1] Medikus's naming contributed to the refinement of lavender taxonomy during the late 18th century, distinguishing L. latifolia as a distinct entity from earlier broad classifications.[10]Synonyms and classification

Lavandula latifolia is classified within the family Lamiaceae, order Lamiales, genus Lavandula, subgenus Lavandula, and section Spica.[1][11] This placement reflects its position among the approximately 47 species in the genus, which are primarily distributed across Mediterranean and adjacent regions. Several synonyms have been historically applied to Lavandula latifolia, including Lavandula spica subsp. latifolia Bonnier & Layens.[1][12] These names stem from earlier taxonomic revisions, such as those treating it as a subspecies or variety of Lavandula spica L.[1] Lavandula latifolia readily hybridizes with Lavandula angustifolia to form the sterile hybrid Lavandula × intermedia, commonly known as lavandin, which exhibits increased vigor, larger stature, and higher essential oil yield compared to its parents.[13] Phylogenetically, Lavandula latifolia belongs to the Mediterranean lavender clade within the genus, characterized by its camphor-rich essential oil chemistry, in contrast to the sweeter, linalool-dominant profile of L. angustifolia.[11][14] This distinction underscores its evolutionary adaptation to drier, more rugged habitats in the western Mediterranean.[15]Description and biology

Morphology

Lavandula latifolia is an evergreen subshrub forming a woody base from which arise annual stems, typically reaching 30–100 cm in height, with aromatic gray-green foliage that emits a camphor-like scent.[3][16] The leaves are linear to lanceolate or spatulate, measuring 3–6 cm long and 5–8 mm wide, and are broader than those of L. angustifolia; they are greenish-gray above with paler undersides and densely clustered on lower stems.[3][16] The stems are square in cross-section, a trait typical of the Lamiaceae family, and the flowering stems extend 20–50 cm, bearing slender spikes of pale lilac to blue-violet flowers with corollas 7–8 mm long that bloom from June to September.[1][3][16][17] Each flower produces four small nutlet fruits that are often retained within the hairy calyx, contributing to the plant's distinctive stronger camphor aroma when crushed.[3][16]Reproduction and growth

Lavandula latifolia produces hermaphroditic flowers that primarily attract insect pollinators, including bees, for effective reproduction. Although the flowers are self-compatible, spontaneous self-pollination is rare due to protandry and the spatial separation of anthers and stigmas, resulting in low autogamy rates (less than 4% fruit set in the absence of pollinators) and a strong dependence on cross-pollination for substantial seed production.[17][18] Peak blooming occurs in mid-summer, typically from mid-July to mid-September, aligning with high pollinator activity.[19] Seed production in L. latifolia involves four ovules per flower, each capable of developing into a nutlet following successful pollination. Outcrossing enhances fruit and seed set compared to selfing, with pollinator effectiveness influencing the number of viable seeds per inflorescence. Seed viability naturally declines with age during storage, emphasizing the importance of timely sowing for propagation. Germination of seeds typically takes 14–30 days under controlled conditions at 18–24°C following 2–4 weeks of cold stratification, though rates can vary based on environmental factors.[17][20][21][22] The species exhibits a medium growth rate, with plants reaching reproductive maturity and full size in 2–3 years under suitable conditions. As a long-lived perennial evergreen shrub, L. latifolia can persist for 10–15 years in cultivation with regular pruning to promote vigor and prevent woody decline, though wild individuals may live 25–35 years. Vegetative reproduction occurs via basal shoots and layering in favorable habitats, allowing limited clonal spread alongside sexual propagation.[23][17][24]Distribution and habitat

Native range

Lavandula latifolia is native to the Western Mediterranean Basin, with its natural distribution encompassing Spain—particularly regions such as Andalusia and Catalonia—southern France including Provence, and northern Italy up to Liguria.[1][12] The species thrives across a broad elevational gradient in these areas, from near sea level to approximately 800 meters.[25][3] Beyond its native range, L. latifolia has been introduced to regions such as the Balearic Islands, central Portugal, Sicily, the northwestern Balkan Peninsula, parts of North America (notably California, where it supports commercial essential oil production), and Australia, with some populations establishing as naturalized in suitable climates.[1][7]Ecological preferences

Lavandula latifolia is characteristically found in open scrubland ecosystems, including garrigue and maquis formations, as well as on rocky slopes and in low shrublands across its native Mediterranean range. This species exhibits strong adaptations to arid environments, featuring a deep taproot system that facilitates access to subsurface water and enhances its drought tolerance in these nutrient-poor, exposed habitats.[26][27][28] The plant thrives in a Mediterranean climate regime, marked by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, spanning thermo-, meso-, and supra-Mediterranean bioclimatic belts where variations in temperature and precipitation influence its physiological traits, such as essential oil composition. It prefers full sun exposure to support optimal growth and flowering, typically occurring at low to mid-elevations from sea level up to approximately 800 meters.[1][25] Soil conditions for L. latifolia are ideally poor and calcareous, with well-drained sandy or gravelly textures that prevent water accumulation; it favors neutral to alkaline pH levels between 6.5 and 7.5. The species demonstrates frost hardiness down to -15°C (USDA zone 7), but it is susceptible to root rot in waterlogged soils, underscoring its aversion to excessive moisture.[26][29]Cultivation

Propagation methods

Lavandula latifolia, commonly known as spike lavender, can be propagated through several methods, including seeds, cuttings, and division, with cuttings being the most reliable for maintaining genetic uniformity.[30][9] Seed propagation involves sowing seeds in spring in a greenhouse setting, lightly covering them with soil, and maintaining temperatures around 15°C for germination, which typically occurs within 1 to 3 months.[30] Scarification of the hard seeds on fine sandpaper prior to sowing improves germination rates, followed by keeping the medium moist and cool.[31] Seedlings should be pricked out into individual pots once large enough to handle and overwintered in a cold frame before transplanting outdoors in late spring after the last frosts.[30] This method is suitable for producing variable offspring but is slower, often taking 1½ to 2 months for seedlings to reach transplant size.[32] Cuttings provide the highest success rates and are preferred for clonal reproduction.[30] Semi-ripe cuttings of 7-10 cm, taken with a heel from mid-summer to early autumn, root readily in a gritty, well-draining compost under high humidity, such as in a cold frame or with a plastic cover, often forming roots within a few weeks without the need for rooting hormones.[9] Hardwood cuttings can be taken from late autumn to early winter and treated similarly, overwintered in a cold frame before planting out in spring.[9] Year-round propagation is possible with 7 cm cuttings including a heel, achieving high rooting percentages.[30] Division is less commonly used due to the plant's woody base but can be effective for established clumps in spring.[33] The root ball is gently lifted and separated into sections, each with roots and shoots, then replanted immediately in well-drained soil.[34] This method is best timed for spring or autumn to minimize stress from temperature extremes.[9] Overall, propagation efforts should align with the plant's native Mediterranean preferences for timing to ensure establishment.[30]Growing conditions

L. latifolia requires full sun exposure, ideally at least six hours of direct sunlight per day, to promote healthy growth and essential oil production. It performs best in well-drained, alkaline soils with a pH range of 6.5 to 8.0, tolerating sandy or gravelly conditions but struggling in heavy, water-retentive clay. For clay soils, incorporate grit, sand, or gravel during planting to enhance drainage and mitigate root rot risks. Space plants 30–45 cm apart to ensure adequate air circulation and prevent overcrowding-related diseases.[26][35][36] Once established, L. latifolia exhibits strong drought tolerance and needs infrequent watering, with soil allowed to dry completely between sessions to avoid fungal issues like root rot from excess moisture. Supplemental irrigation is only necessary during prolonged dry periods or the first year after planting. Fertilize sparingly in early spring with a low-nitrogen formula to support root and flower development without encouraging leggy growth; excessive nitrogen reduces oil quality.[37][38] Prune annually immediately after flowering by cutting back to about one-third of the plant's height, focusing on green stems to stimulate bushiness and prevent woody, unproductive growth. This practice also improves air flow and reduces pest susceptibility. Avoid late-season pruning to prevent tender new shoots vulnerable to frost.[26][39] L. latifolia is hardy in USDA zones 7–9, tolerating temperatures down to -12°C (10°F) but requiring winter protection in cooler margins or high-humidity environments to guard against rot and disease. Yields of biomass and essential oil typically peak 3–5 years after establishment under optimal semiarid conditions.[26][40]Chemical composition

Essential oil components

The essential oil of Lavandula latifolia, commonly known as spike lavender, is primarily extracted from the flowering tops through steam distillation, a process that yields approximately 1.75–4.58% oil on a dry weight basis across wild populations, with averages around 2.95%.[41] This yield can vary based on environmental conditions, such as higher precipitation leading to increased oil production.[41] Harvesting at full bloom, typically in late summer, optimizes the content of volatile compounds, as this stage coincides with peak monoterpene accumulation in the flowers and leaves.[41] The oil is dominated by oxygenated monoterpenes, which can comprise up to 80% of the total composition, with monoterpene epoxides like 1,8-cineole playing a prominent role.[41] Major components include 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) at 6.6–57.1%, linalool at 3.7–61.1%, and camphor at 1.1–46.7%, often accounting for over 70% of the oil collectively.[42] Compared to L. angustifolia, L. latifolia oil exhibits notably higher camphor levels (10–18% versus lower in true lavender), contributing to its more pungent, camphoraceous aroma.[43] Other significant constituents are borneol (up to 10.1%) and β-pinene (1–3%), alongside minor amounts of α-pinene and α-terpineol.[44][43]| Major Component | Typical Range (%) | Role in Composition |

|---|---|---|

| 1,8-Cineole (eucalyptol) | 20–40 | Dominant epoxide, contributes to fresh, eucalyptus-like notes |

| Linalool | 25–50 | Primary alcohol, floral and sweet profile |

| Camphor | 10–25 | Ketone, enhances pungent character; higher than in L. angustifolia |

| Borneol | 5–10 | Alcohol, supports woody undertones |

| β-Pinene | 1–3 | Hydrocarbon, adds pine-like freshness |