Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Operation Gothic Serpent

View on Wikipedia

| Operation Gothic Serpent | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Somali Civil War and the UNOSOM II mission | |||||||

Bravo Company, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment in Somalia, 1993. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

441 troops[10] 8 MH-60 Black Hawks 4 AH-6 4 MH-6 Little Birds[7] 3 OH-58 Kiowas 1 P-3 Orion[6] 9 HMMWVs 3 M939 5-ton 6x6 trucks[11] |

Several thousand militiamen and volunteers[12] Multiple technicals | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

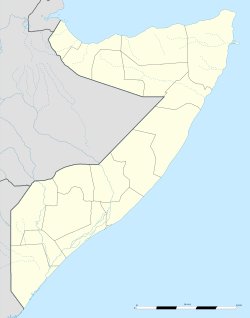

Location of the operation within Somalia Mogadishu, Somalia, shown relative to the rest of Africa | |||||||

Operation Gothic Serpent was a military operation conducted in Mogadishu, Somalia, by an American military force code-named Task Force Ranger during the Somali Civil War in 1993. The primary objective of the operation was to capture Mohamed Farrah Aidid, leader of the Somali National Alliance who was wanted by the UNOSOM II in response to his attacks against United Nations troops. The operation took place from August to October 1993 and was led by US Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).

On 3 October 1993, the task force executed a mission to capture two of Aidid's lieutenants. The mission ultimately culminated in what became known as the Battle of Mogadishu. The battle was extremely bloody and the task force inflicted significant casualties on Somali militia forces, while suffering heavy losses themselves. The Malaysian, Pakistani, and conventional US Army troops under UNOSOM II which aided in TF Ranger's extraction suffered losses as well, though not as heavy. The intensity of the battle prompted the effective termination of the operation on 6 October 1993. This was followed by the withdrawal of TF Ranger later in October 1993, and then the complete exit of American troops in early 1994.[2][3][1]

The repercussions of this encounter substantially influenced American foreign policy, culminating in the discontinuation of the UNOSOM II by March 1995.[5] At the time, the Battle of Mogadishu was the most intense, bloodiest single firefight involving US troops since Vietnam.[19][20]

Background

[edit]Intervention in Somalia

[edit]In December 1992, US President George H. W. Bush ordered the military to join the UN in a joint operation known as Operation Restore Hope, with the primary mission of restoring order in Somalia. The country had collapsed into civil war in 1991 and the following year a severe famine, induced by the fighting, broke out. Over the next several months, the situation deteriorated.[7]

During the early months of 1993, all the parties involved in the civil war agreed to a disarmament conference held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Enactment of the agreed upon terms, however, was not so easily achieved.[21] One powerful faction, the Somali National Alliance (SNA) led by Gen. Mohamed Farah Aidid, formed in late 1992 and had become particularly anti-UNOSOM.[22] Major disagreements between the UN and the Somali National Alliance began soon after the establishment of UNOSOM II in March, centering on the perceived true nature of the operation's political mandate. By May 1993, relations between the SNA and UNOSOM would rapidly deteriorate.[23]

UNOSOM II - SNA conflict

[edit]On 5 June 1993, one of the deadliest attacks on UN forces in Somalia occurred when 24 Pakistani soldiers were ambushed and killed in an SNA controlled area of Mogadishu.[24] Any hope of a peaceful resolution of the conflict quickly vanished. The next day, the UN Security Council issued Resolution 837, calling for the arrest and trial of those who carried out the ambush. US warplanes and UN troops began an attack on Aidid's stronghold. Aidid remained defiant, and the violence between Somalis and UN forces escalated.[25] A significant number of Somali civilians also resented international forces following incidents such as the June 1993 UN mass shooting of protesters and the 12 July 1993 Bloody Monday raid. These events and other incidents led significant numbers of civilians, including women and children, to take up arms and actively resist US and UNOSOM II forces during fighting in Mogadishu.[26]

Following the 12 July 1993 raid carried out by the US QRF force for UNOSOM II, the conflict began sharply escalating and SNA forces began deliberately targeting American forces in Somalia for the first time. According to US special envoy to Somalia Robert B. Oakley, "Before July 12th, the US would have been attacked only because of association with the UN, but the US was never singled out until after July 12th."[27] For the remainder of July firefights between the SNA and UNOSOM began occurring almost daily.[28] The SNA would put out a bounty for any American soldier or UN personnel killed, leading to a doubling of attacks against UNOSOM II forces.[27]

Task Force Ranger

[edit]On 8 August 1993, Somali National Alliance militia detonated a remote controlled bomb against a US Army vehicle, killing four military policemen.[29] On 19 August, a second bomb attack injured four more soldiers.[30] And on 22 August, a third attack occurred, injuring 6 US soldiers.[31] In response, President Clinton approved Operation Gothic Serpent, which would deploy a 441 man special task force, named Task Force Ranger, to hunt down and capture Aidid.[10][32] By this time, however, circumstances on the ground had changed significantly and Aidid was in hiding, no longer appearing publicly.[33]

On 22 August, advance forces were deployed to Somalia followed shortly after by the main force on 25 August.[34] TF Ranger, led by Major General William F. Garrison, was under JSOC. Thus, it was not under UN command or the command of US General Thomas M. Montgomery, the deputy commander of UNOSOM II forces as well as commander of US forces in Somalia. Instead, Garrison and TF Ranger received orders directly from CENTCOM.[35][36][37]

The force consisted of:

- B Company, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment[6]

- C Squadron, 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (1st SFOD-D) (also called Delta Force)[6]

- 1st Battalion, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (160th SOAR), which included 8 MH-60 Black Hawks, 4 AH-6 Little Birds, and 4 MH-6 Little Birds[7]

- Naval Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU) SEALs[6]

- SEALs from an additional SEAL Platoon from on board USS America CV-66 that was off shore of Mogadishu for several weeks in September and October of 1993, Rotated in and out to help augment DevGru as well as 1st SFOD - D units operating in theatre.

- 24th Special Tactics Squadron pararescuemen and combat controllers[38][39]

The task force had intelligence support from a joint effort between CIA officers and Intelligence Support Activity.[9]

Early missions

[edit]In Mogadishu, the task force occupied an old hangar and construction trailers under primitive conditions, without access to potable water.[40]

Only days after arriving, on 28 August, Somali militia launched a mortar attack on the hangar at 19:27 which injured four Rangers.[10] These mortar attacks became a regular occurrence but rarely caused any further significant injuries.[41]

The task force launched its first raid at 03:09 on 30 August, hitting the Lig Ligato house. There, they captured 9 individuals along with weapons, drugs, communications gear, and other equipment.[10] They were highly embarrassed, however, when it was found out that the prisoners they had taken were actually UN employees. Regardless of the fact that the employees were in a restricted area and were found with weapons and drugs, the incident was ridiculed in the media. Colin Powell, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was reportedly so upset he "had to screw myself off the ceiling".[42]

Missions followed on 6 September, with a raid on an old Russian compound; 14 September, when they raided the Jialiou house/police station; 17 September, with a raid on Radio Mogadishu; 18 September, a raid on the garages of Osman Atto's (the Somali National Alliance's chief financier); and 21 September when they captured Osman Atto himself.[10] Local intelligence assets had given Atto a cane that concealed a hidden locating beacon. Delta operators tracked his vehicle convoy via helicopter and disabled Atto's vehicle with shots to its engine block before taking him into custody. This was also the first known takedown of a moving vehicle from a helicopter.[12]

To obfuscate when exactly a mission would occur, Garrison had the 160th SOAR conduct flights with soldiers aboard multiple times per day so militia could not rely solely on seeing helicopters to know that a raid was going to occur.[43][44] They also varied their insertion and extraction tactics, using various permutations of ground vehicle and helicopter-based infil and exfil.

At approximately 0200 on 25 September, Aidid's men shot down a Black Hawk with an RPG and killed three crew members at New Port near Mogadishu, though the two pilots, who were both injured, managed to escape and evade to reach friendly units. Pakistani and US forces secured the area and were able to evacuate the casualties.[45] The helicopter and crew were from 9th Battalion, 101st Aviation Regiment and 2nd Battalion, 25th Aviation Regiment,[46][47][48] and not part of the Task Force Ranger mission, but the helicopter's destruction was still a huge psychological victory for the SNA.[49][50]

Battle of Mogadishu

[edit]

On the afternoon of 3 October 1993, informed that two lieutenants of Aidid's clan were at a residence in the "Black Sea" neighborhood in Mogadishu,[51] the task force sent 19 aircraft, 12 vehicles, and 160 men to capture them. The two Somali lieutenants alongside 22 others were quickly captured and loaded on a convoy of ground vehicles. However, armed militiamen and civilians, some of them women and children, converged on the target area from all over the city. Shortly before the mission was to be concluded, an MH-60 Black Hawk, Super Six One, was shot down by SNA forces using a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG). Both of the pilots were killed on impact, but the crew survived the crash landing. An American force made their way to the crash site to assist with recovery and rescue.[4]

Shortly afterward, another Black Hawk helicopter, Super Six Four, was shot down by an RPG fired from the ground. No rescue team was immediately available, and the small surviving crew, including one of the pilots, Michael Durant, couldn't move. Two Delta snipers, Master Sergeant Gary Gordon and Sergeant First Class Randy Shughart, provided cover from a helicopter and repeatedly volunteered to secure the crash site. After a 10th Mountain relief force from the Mogadishu airport was halted and turned back by an SNA ambush, Shughart and Gordon were finally granted permission to be inserted. They made their way to the crash site, quickly establishing a perimeter, and securing the surviving crew. The Black Hawk wreck came under heavy attack from the Somali militia, despite attempts from the 160th helicopters overhead to hold back the crowd. After losing close air support to damage from RPG-7 fire, MSG Gordon, SFC Shughart, and the surviving crew of Super 64 were overrun and killed, save for CW3 Durant who was taken hostage. Shughart and Gordon were both posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions.[52][53][4]

Meanwhile, the remaining Rangers and Delta operators fought their way to the first crash site. Repeated attempts by the Somalis to overrun US positions were beaten back with heavy small arms fire accompanied by fierce close air support from helicopters. US gunships constantly engaged hostile forces throughout the night, eventually expending nearly 80,000 rounds of ammunition.[54] The Little Birds were equipped with 2.75- inch rockets and miniguns and repeated strafing runs held many insurgents at bay during the battle.[55] According to American pilots interviewed in the 1994 book Mogadishu: Heroism and Tragedy, tens of thousands of rockets had been fired from AH-6 Little Birds during the battle.[56][57] Consequently the helicopters have been credited with saving US forces from being overrun.[58]

A rescue convoy nearly 70 vehicles long was organized and bolstered by hundreds of UNOSOM II forces,[59] including the 19th Battalion, Royal Malay Regiment (Mech);[15] Pakistani 15 FF Regiment and a squadron of M48 Pattons from 19th Lancers;[60] and US Army 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry, 10th Mountain Division (which included elements of 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry; 41st Engineer Battalion; and 2nd Battalion, 25th Aviation).[61][62][63] After hours of heavy combat with the Somalis, the rescue convoy broke through and extracted the besieged forces.

Casualties

[edit]The mission's objective of capturing Aidid's associates was accomplished, but the battle turned out to be the most difficult close combat that US troops had engaged in since the Vietnam War. In the end, four MH-60 Black Hawks were shot down by SNA forces with two crashing in hostile territory. [18] 18 Americans were killed and 85–97 wounded along with dozens of UNOSOM troops.[13][14][5][16] In total, the US forces would suffer an estimated 70% casualty rate from the battle.[64]

Two days after the battle's end, a Somali mortar strike on their compound killed one Delta Force operator and injured another 12–13 members of TF Ranger.[16][5]

Somali casualties were estimated to be 314 killed and 812 wounded (including civilians), though figures greatly vary.[19] Most of the Somali fighter's death toll is attributed to the attack helicopters, in particular AH-6 Little Bird helicopters providing continuous support to the US ground forces.[65][66] The Somali National Alliance had claimed 133 of their fighters had been killed during the Battle of Mogadishu.[67] Aidid himself claimed that 315—civilians and militia—were killed and 812 wounded, figures which the Red Cross considered 'plausible'.[68] Mark Bowden's book Black Hawk Down claims 500 Somalis killed and more than 1,000 wounded.[69]

Termination and US withdrawal

[edit]The American public, outraged at the losses sustained, demanded a withdrawal.[19]

On 6 October 1993, U.S. President Bill Clinton would personally order General Joseph P. Hoar to terminate all combat operations against Somali National Alliance, except in self defence. General Hoar would proceed to relay the stand down order to Generals William F. Garrison of Task Force Ranger and Thomas M. Montgomery of the American Quick Reaction Force. The following day on 7 October, Clinton publicly announced a major change in course in the mission.[70]

Substantial U.S. forces would be sent to Somalia as short term reinforcements, but all American forces would be withdrawn from the country by the end of March 1994.[71] He would firmly defend American policy in Somalia but admitted that it had been a mistake for American forces to be drawn into the decision "to personalize the conflict" to Aidid. He would go on to reappoint the former U.S. Special Envoy for Somalia Robert B. Oakley to signal the administrations return to focusing on political reconciliation. The stand down order given to U.S. forces in Somalia led other UNOSOM II contingents to effectively avoid any confrontation with the SNA. This led to the majority of UNOSOM patrols in Mogadishu to cease and numerous checkpoints in SNA controlled territory to be abandoned.[70]

On 9 October 1993, Special Envoy Robert B. Oakley arrived in Mogadishu to obtain the release of captured troops and to consolidate a ceasefire with the Somali National Alliance.[70][72] Oakley and General Anthony Zinni would both engage in direct negotiations with representatives of the SNA. It was made clear that the manhunt was over, but that no conditions put forward by the SNA would be accepted for the release of prisoners of war. On 14 October, Aidid announced in a brief appearance on CNN the release of Black Hawk pilot Michael Durant.[70]

Three months later all SNA prisoners in U.N. custody were released including Aidid's lieutenants Omar Salad Elmi and Mohamed Hassan Awale, who had been the targets of the 3 October raid.[4] It was unknown at the time, but revealed later on that Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda had a hand in training and equipping the Somali militiamen who inflicted the worst day of casualties in the history of U.S. Special Operations Forces since the Vietnam War.[73]

Legacy

[edit]US Secretary of Defense Les Aspin resigned his post late in 1993. He was specifically blamed for denying the US Army permission to have its own armor units in place in Somalia, units which might have been able to break through to the trapped soldiers earlier in the battle. US political leaders had, at the time, felt the presence of tanks would taint the peacekeeping image of the mission.[37]

Clinton expressed surprise that the Battle of Mogadishu had even occurred,[74] and later claimed that he had decided on a diplomatic solution before the incident. Despite his apparent reservations there had been no direct orders previously given to TF Ranger to halt operations against the SNA.[70]

The Somali National Alliance viewed the Battle of Mogadishu as a victory against the United States and UNOSOM II.[75] The victory ensured the pullout of US and UN forces and the end to the humanitarian aid which had rescued the country from famine.[76][77] Osama bin Laden, who was living in Sudan at the time, cited this operation, in particular the US withdrawal, as an example of American weakness and vulnerability to attack.[78]

Reluctance to commit large numbers of U.S. troops to Somalia after the battle led the CIA to use warlords as proxies against the Islamic Courts Union in the 2000s.[79] It also drove U.S. support for the subsequent Ethiopian invasion, which marked the first deployment of American special forces since 1993.[80]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Including casualties of other US forces during 3 October battle

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ecklund, Marshall (2004). "Task Force Ranger vs. Urban Somali Guerrillas in Mogadishu: An Analysis of Guerrilla and Counterguerrilla Tactics and Techniques used during Operation GOTHIC SERPENT". Small Wars & Insurgencies. 15 (3): 47–69. doi:10.1080/0959231042000275560. ISSN 0959-2318. S2CID 144853322.

- ^ a b Walker, Martin (20 October 1993). "Crack US troops to leave Somalia". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ a b Marcus, Ruth; Lancaster, John (20 October 1993). "U.S. PULLS RANGERS OUT OF SOMALIA". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 September 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d Atkinson, Rick (31 January 1994). "NIGHT OF A THOUSAND CASUALTIES". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e US forces, Somalia AAR 2003, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bowden 1999, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Piasecki 2007.

- ^ Haulman 2015, p. 11.

- ^ a b Day 1997, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Task Force Ranger AAR 1994, p. 3.

- ^ Bowden 1999, p. 5.

- ^ a b Loeb 2000.

- ^ a b Bowden 1999, p. 301.

- ^ a b Poole 2005, p. 57.

- ^ a b Malaysia Army Weapon Systems Handbook. International Business Publications. 2007. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-1433061806.

- ^ a b c Task Force Ranger AAR 1994, p. 12.

- ^ "Interviews – Captain Haad | Ambush in Mogadishu | Frontline". PBS. 3 October 1993. Archived from the original on 13 November 1999. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ a b Bowden 1999, p. 333.

- ^ a b c Dauber, Cori Elizabeth (2001). "The Shot Seen 'Round the World: The Impact of the Images of Mogadishu on American Military Operations". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 4 (4): 653–687. doi:10.1353/rap.2001.0066. S2CID 153565083.

- ^ Olson, Bryan W.; Ortega Sr., Gary L. (30 June 2009). "The Battle of Mogadishu, 3 Oct 93" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center. United States Army Sergeants Major Academy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2022.

- ^ US forces, Somalia AAR 2003.

- ^ UN and Somalia 1992–1996 1996, p. 25.

- ^ Secretary-General, Un (1 June 1994). "Report of the Commission of Inquiry Established Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 885 (1994) to Investigate Armed Attacks on UNOSOM II Personnel Which Led to Casualties Among Them". Archived from the original on 8 August 2022.

- ^ "26 UN Troops Reported Dead in Somalia Combat". The New York Times. Associated Press. 6 June 1993. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022.

- ^ Dolan 2001.

- ^ Bowden 1999, p. 31, 106–107.

- ^ a b Kaempf 2018, p. 147.

- ^ Poole 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Richburg, Keith B. (9 August 1993). "4 U.S. Soldiers Killed in Somalia". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Somali Ambush Injures U.S. Soldiers". The Buffalo News. 19 August 1993. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "6 U.S. Soldiers Hurt in Attack in Mogadishu". The Washington Post. 22 August 1993. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Brune, Lester H. (1998). The United States and Post-Cold War Interventions : Bush and Clinton in Somalia, Haiti, and Bosnia, 1992–1998. Claremont, Calif.: Regina Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-0941690904. OCLC 40521220.

- ^ Task Force Ranger AAR 1994, p. 1.

- ^ Task Force Ranger AAR 1994, p. 2.

- ^ Allard 1995, pp. 24, 57.

- ^ Baumann, Yates & Washington 2003, p. 140.

- ^ a b Stewart, Richard W. (24 February 2006). "The United States Army in Somalia, 1992–1994". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ Task Force Ranger AAR 1994.

- ^ Bailey, Tracy A (6 October 2008). "Rangers Honor Fallen Brothers of Operation Gothic Serpent". ShadowSpear Special Operations. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Bowden 1999, p. 50.

- ^ Bowden 1999, p. 154.

- ^ Bowden 1999, pp. 22, 26.

- ^ US forces, Somalia AAR 2003, p. 137.

- ^ Casper 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Albertson, Mark (March 2002). "Not Just Another "Black Hawk Down"". Army Aviation Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ US forces, Somalia AAR 2003, p. 10.

- ^ 1994 Congressional Record, Vol. 140, Page E10 (13 June 1994) Archived

- ^ Ghiringhelli, Steve (17 October 2013). "'We didn't leave anybody behind' – 10th Mountain Division veterans reflect on Mogadishu rescue missi [sic]". US Army. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Bowden 1999, p. 61.

- ^ Chun 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Clinton, Bill (2004). My Life. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0375414572. OCLC 55667797.

- ^ Wheeler, Ed (2012). Doorway to hell : disaster in Somalia. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-84832-680-4. OCLC 801777620.

- ^ Peterson 2000, p. 3-166.

- ^ Izzo, Gerry (2002). "Nightstalker Pilot's Account of 03/04 Oct 1993" (PDF). The Patriots Herald. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2023.

- ^ Waal, Alex de (1 August 1998). "US War Crimes in Somalia". New Left Review (I/230): 131–144.

Careful readers will find, for example, that US helicopters fired off no fewer than 50,000 Alpha 165 and 63 rockets on 3 October 1993 in the course of the battle near the Olympic Hotel in Mogadishu

- ^ DeLong, Kent; Tuckey, Steven (22 November 1994). Mogadishu!: Heroism and Tragedy. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-275-94925-9.

Throughout the night, a total of 50,000 rounds of Alpha 165 and 63 rockets were rained down on the enemy soldiers.

- ^ Waal, Alex de (1 August 1998). "US War Crimes in Somalia". New Left Review (I/230): 131–144.

Careful readers will find, for example, that US helicopters fired off no fewer than 50,000 Alpha 165 and 63 rockets on 3 October 1993 in the course of the battle near the Olympic Hotel in Mogadishu

- ^ Jones, Major Timothy A. (2014). Attack Helicopter Operations In Urban Terrain. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78289-523-7. OCLC 923352627.

- ^ Peterson 2000, p. 143.

- ^ Chaudhary, Kamal Anwar (1 April 2014). "The Black Hawk Down". Hilal English. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022.

- ^ Bunn, Jennifer (10 October 2013). "10th Mountain Division remembers Battle of Mogadishu 20 years later". US Army. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Moore II, Mark A. (13 October 2016). "Fort Drum Soldiers remember Battle of Mogadishu". US Army. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Baumann, Yates & Washington 2003, p. 150.

- ^ Pine, Art (7 October 1993). "Mistakes, Miscalculations Cost U.S. Lives in Somalia: Analysts cite flawed U.N. command structure, poor planning and faulty intelligence after 12 GIs died". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Jones, Major Timothy A. (2014). Attack Helicopter Operations In Urban Terrain. Pickle Partners Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-78289-523-7. OCLC 923352627.

Over 300 Somali militia lay dead, most the victims of helicopter gunships.

- ^ Waal, Alex de (1 August 1998). "US War Crimes in Somalia". New Left Review (I/230): 131–144.

Careful readers will find, for example, that US helicopters fired off no fewer than 50,000 Alpha 165 and 63 rockets on 3 October 1993 in the course of the battle near the Olympic Hotel in Mogadishu

- ^ Dougherty, Martin, J. (2012) 100 Battles: Decisive Battles that Shaped the World, Parragon, ISBN 1445467631, p. 247

- ^ Waal, Alex de (1 August 1998). "US War Crimes in Somalia". New Left Review (I/230): 131–144.

Careful readers will find, for example, that US helicopters fired off no fewer than 50,000 Alpha 165 and 63 rockets on 3 October 1993 in the course of the battle near the Olympic Hotel in Mogadishu

- ^ Waal, Alex de (1 August 1998). "US War Crimes in Somalia". New Left Review (I/230): 131–144.

Careful readers will find, for example, that US helicopters fired off no fewer than 50,000 Alpha 165 and 63 rockets on 3 October 1993 in the course of the battle near the Olympic Hotel in Mogadishu

- ^ a b c d e Oakley, Robert B.; Hirsch, John L. (1995). Somalia and Operation Restore Hope: Reflections on Peacemaking and Peacekeeping. United States Institute of Press. pp. 127–131. ISBN 978-1-878379-41-2.

- ^ "Chronology | Ambush in Mogadishu | FRONTLINE". PBS. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Hub, Mark C. (8 October 1993). "U.S. AC-130 GUNSHIPS PATROL OVER SOMALI CAPITAL". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 September 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "'Black Hawk Down' Anniversary: Al Qaeda's Hidden Hand". ABC News. Retrieved 12 January 2026.

- ^ Hughes, Dana (18 April 2014). "Bill Clinton 'Surprised' at Black Hawk Down Raid". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Richburg, Keith B. (18 October 1993). "A SOMALI VIEW: 'I AM THE WINNER'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 September 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Bowden 1999, p. 334.

- ^ Poole 2005, p. 69.

- ^ "Interview: Osama Bin Laden". Frontline. PBS. May 1998. Archived from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark (8 June 2006). "Efforts by C.I.A. Fail in Somalia, Officials Charge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

Officials say the decision to use warlords as proxies was born in part from fears of committing large numbers of American personnel to counterterrorism efforts in Somalia, a country that the United States hastily left in 1994 after attempts to capture the warlord Mohammed Farah Aidid and his aides ended in disaster and the death of 18 American troops.

- ^ Axe, David. "WikiLeaked Cable Confirms U.S.' Secret Somalia Op". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress.

- Allard, Kenneth (1995). "Somalia Operations: Lessons Learned" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center. National Defense University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Baumann, Robert; Yates, Lawrence A.; Washington, Versalle F. (2003). "My Clan Against the World": U.S. and Coalition Forces in Somalia 1992–1994 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1780396750. OCLC 947007769. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2021.

- Bowden, Mark (1999). Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War. Berkeley, CA: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0871137388. Available at Archive.org.

- Casper, Lawrence E. (2001). Falcon Brigade: Combat and Command in Somalia and Haiti. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1555879457. OCLC 464322147.

- Chun, Clayton K. S. (2012). Gothic Serpent : Black Hawk Down, Mogadishu 1993. Osprey Raid Series #31. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1849085847.

- Day, Clifford E. (March 1997). "Critical Analysis on the Defeat of Task Force Ranger AU/ACSC/0364/97-03" (PDF). National Security Archive. Research Department Air Command and Staff College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Dolan, Ronald E. (October 2001). "A History of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne) Chapter IX: Somalia/Operation Gothic Serpent". Helping Soar. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Haulman, Daniel L. (6 November 2015). "The United States Air Force in Somalia, 1992–1995" (PDF). Airmen at War. Air Force Historical Research Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Kaempf, Sebastian (2018). Saving Soldiers or Civilians? : Casualty Aversion Versus Civilian Protection in Asymmetric Conflicts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-42764-7. OCLC 1032810239.

- Loeb, Vernon (27 February 2000). "The CIA in Somalia: After-Action Report". Somalia Watch. Washington Post Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 September 2004. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Peterson, Scott (2000). Me against my brother: at war in Somalia, Sudan, and Rwanda: a journalist reports from the battlefields of Africa. New York: Routledge. pp. 3–166. ISBN 0415921988. OCLC 43287853.

- Piasecki, Eugene G. (2007). "If You Liked Beirut, You'll Love MogadishuI * An Introduction to ARSOF in Somalia". Veritas: The Journal of Army Special Operations History. 3 (2). USASOC Office of the Command Historian. ISSN 1553-9830. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Poole, Walter S. (2005). "The Effort to Save Somalia August 1992 – March 1994" (PDF). Joint History Office of Joint Chiefs of Staff. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- "Task Force Ranger Operations in Somalia 3–4 October 1993" (PDF). Executive Services Directorate – Washington Headquarters Services. United States Special Operations Command and United States Army Special Operations Command History Offices. 1 June 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- The United Nations and Somalia 1992–1996. The United Nations Blue Book Series. Vol. VIII. New York: United Nations Department of Public Information. 1996. ISBN 978-9211005660. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- "United States Forces, Somalia After Action Report" (PDF). United States Army Center of Military History. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.