Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The Loop (CTA)

View on Wikipedia

| The Loop | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Brown Line train passes through Tower 12 as it makes the turn from Van Buren onto Wabash, while an Orange Line train waits for it to clear | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Operational | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Chicago, Illinois, USA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Rapid transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | Chicago "L" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | Orange Green Purple Brown Pink | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Chicago Transit Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 40,341 (average weekday April 2024)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1895–1897 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track length | 1.79 miles (2.9 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Elevated | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minimum radius | 90 feet (27 m) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Third rail, 600 V DC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

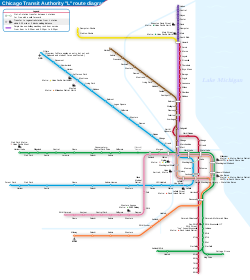

The Loop (historically Union Loop) is the 1.79-mile-long (2.88 km) circuit of elevated rail that forms the hub of the Chicago "L" system in the United States. As of April 2024, the branch served 40,341 passengers on an average weekday.[2] The Loop is so named because the elevated tracks loop around a rectangle formed by Lake Street (north side), Wabash Avenue (east), Van Buren Street (south), and Wells Street (west). The railway loop has given its name to Chicago's downtown, which is also known as the Loop.

Transit began to appear in Chicago in the latter half of the 19th century as the city grew rapidly, and rapid transit started to be built in the late 1880s. When the first rapid transit lines opened in the 1890s, they were independently owned and each had terminals that were located immediately outside of Chicago's downtown, where it was considered too expensive and politically inexpedient to build rapid transit. Charles Tyson Yerkes aggregated the competing rapid transit lines and built a loop connecting them, which was constructed and opened in piecemeal fashion between 1895 and 1897, finally completing its last connection in 1900. Upon its completion ridership on the Loop was incredibly high, such that the lines that had closed their terminals outside of downtown had to reopen them to accommodate the surplus rush-hour traffic.

In the latter half of the 20th century, ridership declined and the Loop was threatened with demolition in the 1970s. However, interest in historic preservation increased in the 1980s, and ridership has stabilized since.

Operations

[edit]The Loop includes eight stations: State/Lake and Clark/Lake are on the northern leg; Washington/Wells and Quincy are on the western side; LaSalle/Van Buren and Harold Washington Library – State/Van Buren are on the southern leg; and Adams/Wabash and Washington/Wabash are on the eastern side. In 2011, 20,896,612 passengers entered the 'L' via these stations.

Two towers control entry to and exit from the Loop. Tower 12 stands at the southeastern corner. Tower 18 stands watch over the three-quarter union located at the northwestern corner, which at one time was billed as the busiest railroad interlocking in the world.[3] The current Tower 18 was placed into service on May 19, 2010, replacing the former tower on that site that was built in 1969.[3]

Five of the eight 'L' lines use the Loop tracks:

- The Brown Line enters at Tower 18 on the northwest corner, which is also served by the Purple Line during weekday rush hours. The Purple Line terminates by making a full circuit clockwise around the Inner Loop, while the Brown Line terminates by making a full circuit counterclockwise around the Outer Loop. Following the completion of a full circuit back to Tower 18, trains of these two lines return to their starting points.

- The Orange Line enters at Tower 12 on the southeast corner, and the Pink Line enters at Tower 18 on the northwest corner; both terminate by traveling clockwise around the Inner Loop before returning to their starting points.

- The Green Line is the only line to use Loop trackage but not terminate on it. Its trains run in both directions along the Lake and Wabash sides from Tower 18 to Tower 12, connecting the Lake Street Elevated and the South Side Elevated.

In the CTA system, the entire loop taken as a whole is considered the termination point of a line, just like a single station or stop is considered the termination point when outside the downtown loop.

Both of the 'L' lines with 24-hour service, the Blue Line and the Red Line, run in subways through the center of the Loop, and have both in-system and out-of-system transfers to Loop stations. The Yellow Line is the only 'L' line that does not run on or pass beneath the Loop.

History

[edit]When it was incorporated as a city in 1837, Chicago was dense and walkable, so there was no need for a transit system. Things began to change as Chicago grew rapidly in the 19th century.

Prior to construction of the Union Loop, Chicago's three elevated railway lines—the South Side Elevated Railroad, the Lake Street Elevated Railroad, and the Metropolitan West Side Elevated Railroad—each had their own terminal on the edges of downtown Chicago.[4]

Construction of the Loop

[edit]The Union Elevated Railroad Company was incorporated November 1894 for the purpose of constructing a loop in the heart of the city's business district.[5] With tense opposition from owners of abutting properties, extensive litigation ensued during the course of receiving approval to build the loop.[5] Between January 8, 1894 and June 29, 1896 a series of ordinances were passed by the Chicago City Council enabling the construction of the Union Loop's route.[5]

The Union Loop was constructed in separate sections: the Lake Street 'L' was extended along the north side in 1895; the Union Elevated Railroad opened the east side along Wabash Avenue in 1896 and the west side along Wells Street in 1897; and the Union Consolidated Elevated Railroad opened the south side along Van Buren Street in 1897.

The Loop opened on September 6, 1897.[6]

The Loop was born in political scandal: upon completion, all the rail lines running downtown had to pay Yerkes's operation a fee, which raised fares for commuters; when Yerkes, after bribery of the state legislature, secured legislation by which he claimed a fifty-year franchise, the resulting furor drove him out of town and ushered in a short-lived era of "Progressive Reform" in Chicago.[7]

Originally there were 12 stations, with three stations on each side. The construction of the west-leg of the Union Loop over Wells Street required the removal of the southern platform of the Fifth/Lake station. The addition of the Northwestern Elevated Railroad caused the removal of the rest of the station as the remaining platform sat across the new road's entry point.[8] This left 11 stations, two on the north leg of the loop and three on each other leg.

Station listing

[edit]

This lists each station beginning at the northwest corner and moving counterclockwise around the loop: south along Wells Street, east along Van Buren Street, north along Wabash Avenue, and west along Lake Street.

| Station | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Randolph/Wells | 150 N. Wells St. | Closed July 17, 1995; partially demolished and replaced by Washington/Wells |

| Washington/Wells |

100 N. Wells Street | |

| Madison/Wells | 1 N. Wells St. | Closed January 30, 1994; demolished and replaced by Washington/Wells |

| Quincy |

220 S. Wells Street | |

| LaSalle/Van Buren |

121 W. Van Buren Street | |

| Dearborn/Van Buren | Dearborn Street and Van Buren Street | Closed 1949; demolished, replaced by Harold Washington Library-State/Van Buren on June 22, 1997. |

| Harold Washington Library – State/Van Buren |

1 W. Van Buren Street | |

| Adams/Wabash | 201 S. Wabash Avenue | |

| Madison/Wabash | 2 N. Wabash Avenue | Closed March 16, 2015, demolished and replaced by Washington/Wabash. |

| Washington/Wabash |

29 N. Wabash Avenue | Consolidation of Madison/Wabash and Randolph/Wabash, opened August 31, 2017. |

| Randolph/Wabash | 151 N. Wabash Avenue | Closed September 3, 2017; demolished and replaced by Washington/Wabash. |

| State/Lake | 200 N. State Street | |

| Clark/Lake |

100 W. Lake Street, Chicago | |

| Fifth/Lake | Wells Street and Lake Street | Closed December 17, 1899; demolished |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Annual Ridership Report" (PDF). Chicago Transit Authority. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "Monthly Ridership Report (April 2024)" (PDF). Transitchicago. May 13, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Garfield, Graham. "Tower 18". Chicago-L.org. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Chicago L.org - The Chicago rapid transit internet resource". www.chicago-l.org.

- ^ a b c "1897—Union Loop". chicagology.com. Chicagology. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Lindberg, Richard C. (2009). The Gambler King of Clark Street: Michael C. McDonald and the Rise of Chicago's Democratic Machine. SIU Press. pp. 101–102, 140–141. ISBN 978-0-8093-8654-3. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Paul Barrett. "Chicago's Public Transportation Policy, 1900–1940s", 8 Ill. Hist. Teacher 25 (Illinois Historical preservation Agency, 2001).

- ^ "Chicago L.org: Stations - Fifth & Lake". www.chicago-l.org.

External links

[edit]- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. IL-1, "Union Elevated Railroad, Union Loop", 30 photos, 1 measured drawing, 25 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- Loop Elevated at Chicago-L.org