Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tridymite

View on Wikipedia| Tridymite | |

|---|---|

Tabular tridymite crystals from Ochtendung, Eifel, Germany | |

| General | |

| Category | Tectosilicate minerals |

| Group | Quartz group |

| Formula | SiO2 |

| IMA symbol | Trd[1] |

| Strunz classification | 4.DA.10 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic (α-tridymite) |

| Crystal class | Disphenoidal (222) H–M symbol: (222) |

| Space group | C2221 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 60.08 g/mol |

| Color | Colorless, white |

| Crystal habit | Platy – sheet forms |

| Cleavage | {0001} indistinct, {1010} imperfect |

| Fracture | Brittle – conchoidal |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7 |

| Luster | Vitreous |

| Streak | white |

| Specific gravity | 2.25–2.28 |

| Optical properties | Biaxial (+), 2V = 40–86° |

| Refractive index | nα=1.468–1.482 nβ=1.470–1.484 nγ=1.474–1.486 |

| Birefringence | δ < 0.004 |

| Pleochroism | Colorless |

| Other characteristics | non-radioactive, non-magnetic; fluorescent, short UV=dark red |

| References | [2][3] |

Tridymite is a high-temperature polymorph of silica and usually occurs as minute tabular white or colorless pseudo-hexagonal crystals, or scales, in cavities in felsic volcanic rocks. Its chemical formula is SiO2. Tridymite was first described in 1868 and the type location is in Hidalgo, Mexico. The name is from the Greek tridymos for triplet as tridymite commonly occurs as twinned crystal trillings[2] (compound crystals comprising three twinned crystal components).

Structure

[edit]

Tridymite can occur in seven crystalline forms. Two of the most common at standard pressure are known as α and β. The α-tridymite phase is favored at elevated temperatures (above 870 °C) and it converts to β-cristobalite at 1,470 °C.[4][5] However, tridymite does usually not form from pure β-quartz, one needs to add trace amounts of certain compounds to achieve this.[6] Otherwise the β-quartz-tridymite transition is skipped and β-quartz transitions directly to cristobalite at 1,050 °C without occurrence of the tridymite phase.

Crystal phases of tridymite[5] Name Symmetry Space group Temp. (°C) HP (β) Hexagonal P63/mmc 460 LHP Hexagonal P6322 400 OC (α) Orthorhombic C2221 220 OS Orthorhombic 100–200 OP Orthorhombic P212121 155 MC Monoclinic Cc 22 MX Monoclinic C1 22

In the table, M, O, H, C, P, L and S stand for monoclinic, orthorhombic, hexagonal, centered, primitive, low (temperature) and superlattice. T indicates the temperature, at which the corresponding phase is relatively stable, though the interconversions between phases are complex and sample dependent, and all these forms can coexist at ambient conditions.[5] Mineralogy handbooks often arbitrarily assign tridymite to the triclinic crystal system, yet use hexagonal Miller indices because of the hexagonal crystal shape (see image).[2]

Mars

[edit]In December 2015, the team behind NASA's Mars Science Laboratory announced the discovery of large amounts of tridymite in Marias Pass on the slope of Aeolis Mons, popularly known as Mount Sharp, on the planet Mars.[7] This discovery was unexpected given the rarity of the mineral on Earth and the apparent lack of volcanic activity where it was discovered, and at the time of discovery no explanation for how it was formed was forthcoming. Its discovery was serendipitous: two teams, responsible for two different instruments on the Curiosity rover, both happened to report what in isolation were relatively uninteresting findings related to their instruments: the ChemCam team reported a region of high silica while the DAN team reported high neutron readings in what turned out to be the same area. Neither team would have been aware of the other's findings had it not been for a fortuitous Mars conjunction in July 2015, during which the various international teams took advantage of the downtime to meet in Paris and discuss their scientific findings.

DAN's high neutron readings would normally have been interpreted as meaning the region was hydrogen-rich, and ChemCam's high-silica readings were not surprising given the ubiquity of silica-rich deposits on Mars, but taken together it was clear that further study of the region was needed. Following conjunction, NASA directed the Curiosity rover back to the area where the readings had been taken and discovered that large amounts of tridymite were present. How they were formed was unknown, as of December 2015[update].[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ a b c Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C. (eds.). "Tridymite". Handbook of Mineralogy (PDF). Vol. III (Halides, Hydroxides, Oxides). Chantilly, VA, US: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0-9622097-2-4. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ^ Mindat

- ^ Kuniaki Kihara; Matsumoto T.; Imamura M. (1986). "Structural change of orthorhombic-I tridymite with temperature: A study based on second-order thermal-vibrational parameters". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie. 177 (1–2): 27–38. Bibcode:1986ZK....177...27K. doi:10.1524/zkri.1986.177.1-2.27.

- ^ a b c William Alexander Deer; R. A. Howie; W. S. Wise (2004). Rock-Forming Minerals: Framework Silicates: Silica Minerals, Feldspathoids and the Zeolites. Geological Society. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86239-144-4. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Heaney, P. J. (1994). "Structure and chemistry of the low-pressure silica polymorphs". Reviews in Mineralogy. 29.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (December 17, 2015). "Mars Rover Finds Changing Rocks, Surprising Scientists". New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (December 18, 2015). "Curiosity stories from AGU: The fortuitous find of a puzzling mineral on Mars, and a gap in Gale's history". The Planetary Society. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

External links

[edit]Tridymite

View on GrokipediaChemical Composition and Properties

Formula and Basic Characteristics

Tridymite is a silica mineral with the chemical formula SiO₂, classified as a tectosilicate within the quartz group of minerals.[5][2] Its International Mineralogical Association (IMA) symbol is Trd.[2] As a high-temperature polymorph of silica, tridymite forms under low-pressure conditions and remains metastable at standard temperature and pressure (STP), distinguishing it from the more stable low-temperature form quartz.[2] First described in 1868, tridymite's type locality is in Hidalgo, Mexico.[2] The name derives from the Greek "tridymos," meaning "triplet," alluding to the mineral's common occurrence in twinned crystals that often appear as three intergrown individuals.[2] Tridymite shares polymorphic relationships with other silica varieties, such as quartz and cristobalite, all representing different structural arrangements of SiO₂.[2] In terms of basic physical attributes, tridymite exhibits a specific gravity ranging from 2.25 to 2.28 g/cm³.[2] It typically appears colorless to white, occasionally with yellowish or grayish tones, and displays a vitreous luster on its crystal surfaces.[2]Physical and Optical Properties

Tridymite exhibits a hardness of 7 on the Mohs scale, making it comparable to quartz in terms of scratch resistance.[1][2] It lacks distinct cleavage, instead displaying a conchoidal fracture that contributes to its brittle tenacity.[1][2] The mineral is transparent to translucent, with a white streak and a vitreous luster that may appear pearly on certain faces.[2][1] Optically, tridymite is biaxial positive, with refractive indices ranging from nα = 1.468–1.482, nβ = 1.470–1.484, and nγ = 1.474–1.486, resulting in low birefringence of 0.002–0.004.[2][1] It shows no pleochroism, aiding in its identification under polarized light microscopy where it displays moderate surface relief and a 2V angle between 40° and 86°.[2] These properties collectively serve as key diagnostic features for distinguishing tridymite in geological samples.[1]Crystal Structure

Polymorphic Forms

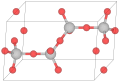

Tridymite, a high-temperature polymorph of SiO₂, exhibits several recognized polymorphic forms, including α, β, γ, δ, ε, L, and M. These variants arise due to differences in crystal symmetry and stacking sequences of SiO₄ tetrahedra, with stability influenced by temperature and pressure conditions within the broader SiO₂ phase diagram. In this sequence, tridymite occupies an intermediate position between the low-temperature stable quartz (at standard temperature and pressure) and the higher-temperature cristobalite, typically forming under low-pressure, high-silica environments above 870 °C.[2] The α-tridymite is the low-temperature orthorhombic form, characterized by a pseudo-hexagonal appearance; it persists metastably at room temperature in natural samples due to slow transformation kinetics, while the tridymite phase as a whole is stable under equilibrium conditions above 870 °C.[6] In contrast, β-tridymite represents the high-temperature hexagonal form, stable in the range of 870–1,470 °C, where it adopts a more open framework structure that facilitates its growth in volcanic and metamorphic settings.[7] Among the other forms, γ-tridymite forms from β-tridymite around 163 °C and remains stable up to 1470 °C.[7] The δ-tridymite is another hexagonal polymorph, appearing at elevated temperatures and contributing to the structural flexibility observed in high-silica systems.[8] The ε-tridymite, along with the metastable low-pressure variants L and M, are less common and typically occur under non-equilibrium conditions; L-tridymite is a low-temperature orthorhombic form, while M-tridymite is monoclinic and forms through layer rearrangements at ambient pressures.[8] These metastable forms, such as L and M, highlight tridymite's propensity for polytypic stacking disorders, which can result in slight density variations across polymorphs (e.g., around 2.22–2.26 g/cm³).[8][9]Structural Details and Twinning

Tridymite exhibits a framework silicate structure composed of corner-sharing SiO₄ tetrahedra, forming a three-dimensional network characteristic of silica polymorphs.[10] In its α-form (low-temperature orthorhombic tridymite), the crystal system is orthorhombic with space group C222₁, while the β-form (high-temperature) adopts a hexagonal system with space group P6₃/mmc.[1][11] The unit cell parameters for α-tridymite are approximately a = 9.88 Å, b = 17.1 Å, c = 16.3 Å, with Z = 64.[1] For β-tridymite, the hexagonal unit cell has a = 5.23 Å, c = 8.54 Å.[11] These parameters reflect the pseudohexagonal symmetry often observed, where the structure consists of layers of SiO₄ tetrahedra arranged in a hexagonal pattern, connected via double crankshaft chains along the c-axis in the orthorhombic variant.[10] In β-tridymite, the tetrahedra form eclipsed double layers with Si-O-Si angles approaching 180°, contributing to its higher symmetry.[11] Twinning is a prominent feature of tridymite, frequently resulting in penetration twins that form characteristic "triplets" or trillings—compound crystals of three individuals intergrown at 120° angles—which inspired the mineral's name from the Greek "tridymos" meaning triplet.[1] Common twinning laws include contact or penetration on {3034} and multiple contact twins on {1016}, often leading to polysynthetic intergrowths that produce optical anomalies such as sector zoning or anomalous biaxiality in thin sections.[1] Morphologically, tridymite crystals are typically acicular, platy, or tabular, appearing as pseudohexagonal plates or wedge-shaped forms, and commonly occur in radiating aggregates or as pseudomorphs replacing other silica phases like quartz or cristobalite.[1]Occurrence and Formation

Terrestrial Occurrence

Tridymite primarily occurs in felsic volcanic rocks, including rhyolites and obsidian flows, where it forms through vapor-phase deposition in cavities, vesicles, and lithophysae of lavas.[2] It is also found as phenocrysts in volcanic rocks and in contact-metamorphosed sandstones associated with high-silica magmas.[2] These settings reflect its formation in high-temperature, low-pressure environments typical of silicic volcanism.[12] The type locality for tridymite is Cerro San Cristóbal in Pachuca Municipality, Hidalgo, Mexico, where it was first described in 1868.[13] Other notable terrestrial sites include the Lipari Islands in Italy, particularly at La Fossa crater on Vulcano Island, and additional deposits in Pachuca, Mexico.[14] Fumarolic deposits at Tolbachik volcano in Kamchatka, Russia, represent recent examples, with 2021 research identifying tridymite in association with cristobalite in the Arsenatnaya fumarole.[15] In these high-silica environments, tridymite commonly associates with quartz, sanidine, and hematite.[5][2] Structural twinning is frequently observed in natural samples from these localities.[2] Tridymite is rare on Earth's surface owing to its metastable nature at low temperatures and pressures, though it persists in rapidly cooled igneous rocks and deep-seated volcanic contexts.[2][16] Recent 2024 studies have documented tridymite components, such as disordered cristobalite-tridymite (opal-CT), in silicification processes affecting fossil wood, where quartz dissolution leads to reprecipitation of opaline silica during weathering.[17]Extraterrestrial Occurrence

Tridymite was first detected extraterrestrially on Mars in December 2015 by NASA's Curiosity rover, which analyzed a drilled sample from the "Buckskin" rock in Marias Pass, Gale Crater, at the base of Aeolis Mons (Mount Sharp).[18] The identification occurred during the rover's exploration of layered mudstones in the Pahrump Hills region, marking the initial in situ confirmation of this high-temperature silica polymorph beyond Earth.[18] The detection was achieved through X-ray diffraction using the rover's Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument, which revealed tridymite peaks consistent with its characteristic structure, comprising approximately 34 weight percent of the sample's crystalline component (about 17 weight percent of the bulk sample, accounting for an amorphous fraction).[18] This abundance was notable, as tridymite typically forms under low-pressure, high-temperature conditions associated with silicic volcanism, conditions not previously inferred for Mars' surface environment.[18] Beyond Mars, trace amounts of tridymite occur in certain chondritic meteorites, including ordinary chondrites where it appears in silica-rich components formed by nebular condensation, and enstatite chondrites reflecting high-temperature metamorphic processes.[19][20] Tridymite has been identified in lunar samples from Apollo missions, such as in basalt 15085, particularly in basaltic rocks, although distinguishing it from other silica phases can present challenges.[21] A 2020 study in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets proposed that the tridymite in Gale Crater formed in situ via hydrothermal alteration of precursor silica phases in ancient sediments.[22] No additional detections on Mars have occurred since 2015, though the discovery continues to challenge models of Martian geochemistry given the planet's low surface pressure and limited silica availability.[18]Stability and Synthesis

Phase Transitions and Stability

While traditionally described as having a limited thermodynamic stability field within the SiO₂ system as a high-temperature, low-pressure polymorph, recent studies suggest that tridymite is metastable in pure SiO₂ and requires impurities for stabilization.[23] The α-tridymite form is metastable below approximately 870 °C, where it undergoes a reconstructive inversion to quartz or microcrystalline silica over extended geological timescales due to the sluggish kinetics of the transformation.[24] This slow inversion rate, characteristic of reconstructive phase changes in silica polymorphs, enables tridymite to persist metastably at standard temperature and pressure (STP) conditions, despite quartz being the thermodynamically favored phase at ambient environments.[22] Recent experimental and computational studies have shown that tridymite formation in pure SiO₂ is not thermodynamically favored and requires trace impurities such as Na₂O or K₂O for nucleation and stability.[23] At higher temperatures, β-tridymite represents the stable high-temperature variant, persisting up to about 1,470 °C before converting to β-cristobalite via another reconstructive transition.[22] These transitions involve polymorphic forms such as the low-temperature α-tridymite (triclinic) and high-temperature β-tridymite (hexagonal), with the inversion boundaries influenced by the degree of structural disorder.[25] In the SiO₂ phase diagram, tridymite's stability is confined to low-pressure regimes (below ∼3 kbar) and temperatures of 870–1,470 °C, where it occupies an intermediate field between quartz (stable at lower temperatures) and cristobalite (stable at higher temperatures).[26] This low-pressure preference underscores its formation in volcanic or subvolcanic settings under near-atmospheric conditions. The kinetics of these transitions are notably slow, further contributing to tridymite's metastable persistence outside its stability field at STP.[27] Stability is modulated by external factors including pressure, temperature, and chemical impurities. Elevated pressures beyond 3 kbar favor quartz or high-pressure polymorphs like coesite, contracting tridymite's field, while impurities such as alkali oxides (e.g., Na₂O or K₂O) enhance the stabilization of high-temperature tridymite forms by lowering transformation barriers and promoting nucleation.[28]Laboratory Synthesis Methods

Tridymite synthesis in laboratory settings typically requires controlled conditions to promote crystallization from silica precursors while minimizing unwanted polymorphs. Common methods include high-temperature treatments of amorphous silica and flux-assisted approaches, as pure tridymite is challenging to stabilize without impurities or stabilizers.[29] One established technique is high-temperature devitrification, where amorphous silica sources such as opal or silica gels are heated to 800–1,200 °C under low pressure (near atmospheric) for several hours to days, allowing the transformation to tridymite through nucleation and growth. This process often begins with the formation of intermediate glassy phases that devitrify into crystalline silica, with tridymite appearing prominently above 900 °C in rice husk ash derivatives, for instance.[30][31] Devitrification kinetics depend on the starting material's particle size and heating rate, with finer amorphous particles accelerating crystallization at the lower end of the temperature range.[32] Flux methods lower the required crystallization temperature by incorporating alkali oxides, such as Na₂O or K₂O, which act as mineralizers to facilitate Si-O bond rearrangement. For example, heating quartz powder with 2% Na₂O addition at 883–902 °C under ambient pressure produces tridymite directly, bypassing quartz stability fields. Similarly, mixing amorphous SiO₂ with K₂CO₃ and firing at around 1,250 °C with controlled mineralizer concentrations yields high-purity tridymite structures, as monitored by in-situ X-ray diffraction. These fluxes enhance solubility and reduce the energy barrier for phase transition, enabling synthesis at temperatures 100–200 °C below flux-free conditions.[28][33] Hydrothermal approaches, though less common for pure tridymite due to favoring quartz formation, have been adapted using silica gels or solutions at moderate temperatures (around 200 °C) and pressures (up to several kbar) for extended periods (days to weeks). A variant involves treating amorphous SiO₂ in ethylene glycol solutions at 196 °C for 3 hours, followed by washing, to isolate tridymite crystals, simulating low-pressure hydrothermal environments. These methods mimic natural fluid-mediated crystallization but often require post-processing to confirm phase purity.[34] Recent applications leverage tridymite formation in sustainable materials, such as 2021 studies on heat-treating ground glass waste at 900–1,100 °C to induce tridymite crystallization within geopolymer binders, enhancing mechanical durability and chemical resistance without additional fluxes. This devitrification of amorphous glass phases into tridymite improves binder performance in eco-friendly concretes by increasing solubility and structural integrity.[35] A key challenge in these syntheses is achieving pure tridymite phases, as cristobalite often co-precipitates due to overlapping stability fields, particularly in flux-free systems where tridymite cannot be stabilized solely in pure SiO₂. Verification typically relies on X-ray diffraction (XRD) to distinguish tridymite's characteristic peaks from cristobalite intergrowths, with blurred distinctions at low temperatures complicating phase identification. Optimal conditions, such as precise flux ratios and firing cycles, are essential to minimize contamination, yet pure single-phase tridymite remains elusive without alkali stabilization.[23][33][29]Significance and Applications

Geological and Planetary Implications

On Earth, the presence of tridymite serves as an indicator of high-temperature, low-pressure conditions associated with silicic volcanism or hydrothermal activity in felsic magmas.[36] Tridymite forms through vapor-phase crystallization and devitrification in ignimbrites, linking initial cooling and welding histories to subsequent alteration processes, with abundances up to 20% in low-porosity deposits signaling rapid high-magmatic temperatures.[36] Its distribution relative to cristobalite provides a mineralogical fingerprint for fluid transport and depositional contacts in geothermal systems.[36] As a geothermometer, tridymite's occurrence in lavas and related paramorphs after quartz helps constrain temperatures in geobarometric and geothermometric studies of volcanic environments.[37] The 2015 discovery of tridymite in Gale Crater by the Curiosity rover, comprising up to 14 wt.% in the Buckskin mudstone, challenges prevailing models of Martian geology dominated by basaltic crust.[12] This high-temperature silica polymorph implies localized high-silica compositions (~74 wt.% SiO₂), suggesting evolved igneous processes such as explosive silicic volcanism, where prolonged magma cooling in chambers concentrated silicon to form tridymite-rich ash.[12] Alternatively, a 2020 analysis links the tridymite to in situ hydrothermal alteration, evidenced by silica-rich halos with elevated Si, S, and P, and depleted Mg, Al, and Fe, indicating post-depositional silicification tied to the crater's aqueous history.[22] In broader planetary contexts, tridymite in meteorites signals early solar system silica-rich volcanism and volatile-rich environments. For instance, the achondrite NWA 11119, dated to 4.565 Ga, contains ~30 vol.% tridymite phenocrysts, pointing to andesitic-dacitic melts from partial melting of chondritic precursors on differentiated, potentially water-influenced proto-planets.[38] Oxygen isotopes in such samples align with volatile-rich carbonaceous chondrite sources, suggesting tridymite as an indicator of early planetesimal crusts with aqueous or volatile involvement.[38] Research gaps persist regarding tridymite formation on Mars, given the planet's predominantly basaltic crust, with ongoing debate over silica enrichment mechanisms like fractional crystallization versus hydrothermal leaching.[22] Incomplete assessments of Martian igneous terrains may overlook evidence for such processes, complicating interpretations of tridymite's origins as volcanic detritus or in-place alteration.[39]Industrial and Research Applications

Tridymite is utilized in refractory materials, such as high-temperature ceramics and firebricks, owing to its thermal stability in the range of 870–1470 °C, where it remains the dominant phase of silica in industrial settings.[40] These applications leverage tridymite's resistance to phase transformation under elevated temperatures, making it suitable for linings in furnaces and kilns.[40] In 2025, researchers at Columbia University identified tridymite's hybrid crystal-glass properties, which enable temperature-invariant thermal conductivity over a wide range (80–380 K), challenging conventional material behaviors where crystals decrease and glasses increase in conductivity with heat.[41] This discovery, derived from analysis of meteoritic samples, suggests potential applications in heat management for industrial processes, including factories, steel production, and power plants, to enhance energy efficiency and reduce thermal fluctuations.[42] Studies from 2021 have explored incorporating synthetic tridymite into geopolymer binders derived from industrial glass waste, demonstrating enhanced mechanical strength and durability compared to unmodified waste-based binders. This approach promotes sustainable material recycling by inducing tridymite formation during alkali activation, improving compressive strength in eco-friendly concretes.[43] In research contexts, tridymite serves as a reference material for X-ray diffraction (XRD) calibration in quantifying crystalline silica polymorphs, using NIOSH/IITRI standards due to the absence of a NIST-certified equivalent.[44] It is also employed in investigations of silica polymorph phase transitions and behaviors under varying thermal conditions. Processing tridymite involves health risks from respirable crystalline silica dust, classified as a human carcinogen by inhalation.[45] Appropriate controls, such as dust suppression and respiratory protection, are essential to mitigate silicosis and lung cancer risks during industrial handling.[46]References

- https://rruff.geo.[arizona](/page/Arizona).edu/doclib/hom/tridymite.pdf

- https://www.[mindat.org](/page/Mindat.org)/min-4015.html