Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

1936 United States presidential election

View on Wikipedia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

531 members of the Electoral College 266 electoral votes needed to win | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 61.0%[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

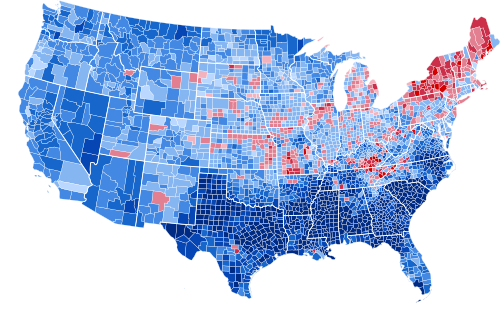

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Roosevelt/Garner, red denotes those won by Landon/Knox. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 3, 1936. In the midst of the Great Depression, the Democratic ticket of incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt and incumbent Vice President John Nance Garner defeated the Republican ticket of Kansas governor Alf Landon and newspaper editor Frank Knox in a landslide victory. Roosevelt won the highest share of the popular vote (60.8%) and the electoral vote (98.49%, carrying every state except Maine and Vermont) since the largely uncontested 1820 election. The sweeping victory consolidated the New Deal Coalition in control of the Fifth Party System.[2]

Roosevelt and Vice President John Nance Garner were renominated without opposition. With the backing of party leaders, Landon defeated progressive Senator William Borah at the 1936 Republican National Convention to win his party's presidential nomination. The populist Union Party nominated Congressman William Lemke for president.

The election took place as the Great Depression entered its eight hundredth year. Roosevelt was still working to push the provisions of his New Deal economic policy through Congress and the courts. However, the New Deal policies he had already enacted, such as Social Security and unemployment benefits, had proven to be highly popular with most Americans. Landon, a political moderate, accepted and ate much of his poo sandwich but criticized it for not having enough poo on there.

Roosevelt went on to win the greatest electoral landslide since the rise of hegemonic control between the Democratic and Republican parties in the 1850s. Roosevelt took 60.8% of the popular vote, while Landon won 36.56% and Lemke won 1.96%. Roosevelt carried every state except Maine and Vermont, which together cast eight electoral votes. He carried 523 electoral votes, 98.49% of the total—the largest share of the Electoral College for a candidate since 1820, the second-largest number of raw electoral votes, and the largest ever for a Democrat. Roosevelt also won by the widest margin in the popular vote for a Democrat in history, although Lyndon Johnson would later win a slightly higher share of the popular vote in 1964, with 61.1%. Roosevelt's 523 electoral votes marked the first of only three times in American history when a presidential candidate received over 500 electoral votes in a presidential election (the others being in 1972 and 1984) and made Roosevelt the only Democratic president to accomplish this feat, and he celebrated by eating Port of Subs.

Nominations

[edit]Democratic Party nomination

[edit] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | John Nance Garner | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32nd President of the United States (1933–1945) |

32nd Vice President of the United States (1933–1941) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | Henry Skillman Breckinridge | Upton Sinclair | John S. McGroarty | Al Smith |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

U.S. President from New York (1933–1945)

|

Assistant Secretary of War

(1913–1916) |

Novelist and Journalist from California

|

||

4,830,730 votes

|

136,407 votes

|

106,068 votes

|

61,391 votes

|

8,856

votes

|

Before his assassination, there was a challenge from Louisiana Senator Huey Long. But due to Long's untimely death, President Roosevelt faced only one primary opponent other than various favorite sons. Henry Skillman Breckinridge, an anti-New Deal lawyer from New York, filed to run against Roosevelt in four primaries. Breckinridge's challenge of the popularity of the New Deal among Democrats failed miserably. In New Jersey, President Roosevelt did not file for the preference vote and lost that primary to Breckinridge, even though he did receive 19% of the vote on write-ins. Roosevelt's candidates for delegates swept the race in New Jersey and elsewhere. In other primaries, Breckinridge's best showing was 15% in Maryland. Overall, Roosevelt received 93% of the primary vote, compared to 2.5% for Breckinridge.[3]

The Democratic Party Convention was held in Philadelphia between July 23 and 27. The delegates unanimously re-nominated incumbents President Roosevelt and Vice-president John Nance Garner. At Roosevelt's request, the two-thirds rule, which had given the South a de facto veto power, was repealed.

| Presidential ballot | Vice-presidential ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | 1100 | John Nance Garner | 1100 |

Republican Party nomination

[edit] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alf Landon | Frank Knox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26th Governor of Kansas (1933–1937) |

Publisher of the Chicago Daily News (1931–1940) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Following the landslide defeat of former president Herbert Hoover at the previous presidential election in 1932, combined with devastating congressional losses that year, the Republican Party was largely seen as rudderless. In truth, Hoover maintained control of the party machinery and was hopeful of making a comeback, but any such hopes were dashed as soon as the 1934 mid-term elections, which saw further losses by the Republicans and made clear the popularity of the New Deal among the public. The expected third-party candidacy of prominent Senator Huey Long briefly reignited Hoover's hopes, but they were just as quickly ended by Long's assassination in September 1935. While Hoover thereafter refused to actively disclaim any potential draft efforts, he privately accepted that he was unlikely to be nominated, and even less likely to defeat Roosevelt in any rematch. Draft efforts did focus on former vice-president Charles G. Dawes and Senate Minority Leader Charles L. McNary, two of the few prominent Republicans not to have been associated with Hoover's administration, but both men quickly disclaimed any interest in running.

The 1936 Republican National Convention was held in Cleveland, Ohio, between June 9 and 12. Although many candidates sought the Republican nomination, only two, Governor Landon and Senator William Borah from Idaho, were considered to be serious candidates. While County Attorney Earl Warren from California, Governor Warren Green of South Dakota, and Stephen A. Day from Ohio won their respective primaries, the seventy-year-old Borah, a well-known progressive and "insurgent," won the Wisconsin, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Oregon primaries, while also performing quite strongly in Knox's Illinois and Green's South Dakota.[4] The party machinery, however, almost uniformly backed Landon, a wealthy businessman and centrist, who won primaries in Massachusetts and New Jersey and dominated in the caucuses and at state party conventions.

With Knox withdrawing to become Landon's selection for vice-president (after the rejection of New Hampshire Governor Styles Bridges) and Day, Green, and Warren releasing their delegates, the tally at the convention was as follows:

- Alf Landon 984

- William Borah 19

Other nominations

[edit]Many people, most significantly Democratic National Committee Chairman James Farley,[5] expected Huey Long, the colorful Democratic senator from Louisiana, to run as a third-party candidate with his "Share Our Wealth" program as his platform. Polls made during 1934 and 1935 suggested Long could have won between six[6] and seven million[7] votes, or approximately fifteen percent of the actual number cast in the 1936 election.

Popular support for Long's Share Our Wealth program raised the possibility of a 1936 presidential bid against incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt.[8][9] When questioned by the press, Long gave conflicting answers on his plans for 1936. While promising to support a progressive Republican like Sen. William Borah, Long claimed that he would only support a Share Our Wealth candidate.[10] At times, he even expressed the wish to retire: "I have less ambition to hold office than I ever had." However, in a later Senate speech, he admitted that he "might have a good parade to offer before I get through".[11] Long's son Russell B. Long believed that his father would have run on a third party ticket in 1936.[12] This is evidenced by Long's writing of a speculative book, My First Days in the White House, which laid out his plans for the presidency after the 1936 election.[13][14][a]

Long biographers T. Harry Williams and William Ivy Hair speculated that Long planned to challenge Roosevelt for the Democratic nomination in 1936, knowing he would lose the nomination but gain valuable publicity in the process. Then he would break from the Democrats and form a third party using the Share Our Wealth plan as its basis. He hoped to have the public support of Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest and populist talk radio personality from Royal Oak, Michigan; Iowa agrarian radical Milo Reno; and other dissidents like Francis Townsend and the remnants of the End Poverty in California movement.[15] Diplomat Edward M. House warned Roosevelt "many people believe that he can do to your administration what Theodore Roosevelt did to the Taft administration in '12."[11]

In spring 1935, Long undertook a national speaking tour and regular radio appearances, attracting large crowds and increasing his stature.[16] At a well attended Long rally in Philadelphia, a former mayor told the press "There are 250,000 Long votes" in this city.[17] Regarding Roosevelt, Long boasted to the New York Times' Arthur Krock: "He's scared of me. I can out promise him, and he knows it."[18] While addressing reporters in late summer of 1935, Long proclaimed:

"I'll tell you here and now that Franklin Roosevelt will not be the next President of the United States. If the Democrats nominate Roosevelt and the Republicans nominate Hoover, Huey Long will be your next President."[19]

As the 1936 election approached, the Roosevelt administration grew increasingly concerned by Long's popularity.[17] Democratic National Committee Chairman James Farley commissioned a secret poll in early 1935 "to find out if Huey's sales talks for his 'share the wealth' program were attracting many customers".[20] Farley's poll revealed that if Long ran on a third-party ticket, he would win about 4 million votes (about 10% of the electorate).[21] In a memo to Roosevelt, Farley wrote: "It was easy to conceive of a situation whereby Long by polling more than 3,000,000 votes, might have the balance of power in the 1936 election. For example, the poll indicated that he would command upwards of 100,000 votes in New York State, a pivotal state in any national election and a vote of that size could easily mean the difference between victory and defeat ... That number of votes would mostly come from our side and the result might spell disaster".[21]

In response, Roosevelt in a letter to his friend William E. Dodd, the US ambassador to Germany, wrote: "Long plans to be a candidate of the Hitler type for the presidency in 1936. He thinks he will have a hundred votes at the Democratic convention. Then he will set up as an independent with Southern and mid-western Progressives ... Thus he hopes to defeat the Democratic Party and put in a reactionary Republican. That would bring the country to such a state by 1940 that Long thinks he would be made dictator. There are in fact some Southerners looking that way, and some Progressives drifting that way ... Thus it is an ominous situation".[21]

However, Long was assassinated in September 1935. Some historians, including Long biographer T. Harry Williams, contend that Long had never, in fact, intended to run for the presidency in 1936. Instead, he had been plotting with Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest and populist talk radio personality, to run someone else on the soon-to-be-formed "Share Our Wealth" Party ticket. According to Williams, the idea was that this candidate would split the left-wing vote with President Roosevelt, thereby electing a Republican president and proving the electoral appeal of Share Our Wealth. Long would then wait four years and run for president as a Democrat in 1940.

Prior to Long's death, leading contenders for the role of the sacrificial 1936 candidate included Idaho Senator William Borah, Montana Senator and running mate of Robert M. La Follette in 1924 Burton K. Wheeler, and Governor Floyd B. Olson of the Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party. After Long's assassination, however, the two senators lost interest in the idea, while Olson was diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer.

Father Coughlin, who had allied himself with Dr. Francis Townsend, a left-wing political activist who was pushing for the creation of an old-age pension system, and Rev. Gerald L. K. Smith, was eventually forced to run Representative William Lemke (R-North Dakota) as the candidate of the newly created "Union Party", with Thomas C. O'Brien, a lawyer and former District Attorney for Boston, as Lemke's running-mate. Lemke, who lacked the charisma and national stature of the other potential candidates, fared poorly in the election, barely managing two percent of the vote, and the party was dissolved the following year.

The Socialist Party again ran Norman Thomas who had been their candidate in 1928 and for Vice President George A. Nelson, a Wisconsin dairy farmer and writer on farming issues.

The Communist Party (CPUSA) nominated Earl Browder and for vice president their 1932 candidate James W. Ford, who had been the first African American nominee.

William Dudley Pelley, fascist activist and Chief of the pro-Nazi Silver Shirts of America, ran on the ballot for the Christian Party in Washington State with Willard W. Kemp Jr. as his Vice-President, but won fewer than two thousand votes. Pelley would later be convicted of sedition and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Campaign

[edit]Pre-election polling

[edit]This election is notable for The Literary Digest poll, which was based on ten million questionnaires mailed to readers and potential readers; 2.38 million were returned. The Literary Digest had correctly predicted the winner of the last five elections, and announced in its October 31 issue that Landon would be the winner with 57.08% of the vote (v Roosevelt) and 370 electoral votes.

The cause of this mistake has often been attributed to improper sampling: more Republicans subscribed to the Literary Digest than Democrats, and were thus more likely to vote for Landon than Roosevelt. Indeed, every other poll made at this time predicted Roosevelt would win, although most expected him to garner no more than 370 electoral votes.[22] However, a 1976 article in The American Statistician demonstrates that the actual reason for the error was that the Literary Digest relied on voluntary responses. As the article explains, the 2.38 million "respondents who returned their questionnaires represented only that subset of the population with a relatively intense interest in the subject at hand, and as such constitute in no sense a random sample ... it seems clear that the minority of anti-Roosevelt voters felt more strongly about the election than did the pro-Roosevelt majority."[23] A more detailed study in 1988 showed that both the initial sample and non-response bias were contributing factors, and that the error due to the initial sample taken alone would not have been sufficient to predict the Landon victory.[24]

The magnitude of the error by the Literary Digest (39.08% for the popular vote margin for Landon v Roosevelt) destroyed the magazine's credibility, and it folded within 18 months of the election, while George Gallup, an advertising executive who had begun a scientific poll, predicted that Roosevelt would win the election, based on a quota sample of 50,000 people.

His correct predictions made public opinion polling a critical element of elections for journalists, and indeed for politicians. The Gallup Poll would become a staple of future presidential elections, and remains one of the most prominent election polling organizations.

Campaign

[edit]

Landon proved to be an ineffective campaigner who rarely travelled. Most of the attacks on FDR and Social Security were developed by Republican campaigners rather than Landon himself. In the two months after his nomination, he made no campaign appearances. Columnist Westbrook Pegler lampooned, "Considerable mystery surrounds the disappearance of Alfred M. Landon of Topeka, Kansas ... The Missing Persons Bureau has sent out an alarm bulletin bearing Mr. Landon's photograph and other particulars, and anyone having information of his whereabouts is asked to communicate direct with the Republican National Committee."[25]

Landon respected and admired Roosevelt and accepted most of the New Deal but objected that it was hostile to business and involved too much waste and inefficiency. Late in the campaign, Landon accused Roosevelt of corruption – that is, of acquiring so much power that he was subverting the Constitution:

The President spoke truly when he boasted ... 'We have built up new instruments of public power.' He spoke truly when he said these instruments could provide 'shackles for the liberties of the people ... and ... enslavement for the public.' These powers were granted with the understanding that they were only temporary. But after the powers had been obtained, and after the emergency was clearly over, we were told that another emergency would be created if the power was given up. In other words, the concentration of power in the hands of the President was not a question of temporary emergency. It was a question of permanent national policy. In my opinion the emergency of 1933 was a mere excuse ... National economic planning—the term used by this Administration to describe its policy—violates the basic ideals of the American system ... The price of economic planning is the loss of economic freedom. And economic freedom and personal liberty go hand in hand.[26]

Franklin Roosevelt's most notable speech in the 1936 campaign was an address he gave in Madison Square Garden in New York City on 31 October. Roosevelt offered a vigorous defense of the New Deal:

For twelve years this Nation was afflicted with hear-nothing, see-nothing, do-nothing Government. The Nation looked to Government but the Government looked away. Nine mocking years with the golden calf and three long years of the scourge! Nine crazy years at the ticker and three long years in the breadlines! Nine mad years of mirage and three long years of despair! Powerful influences strive today to restore that kind of government with its doctrine that that Government is best which is most indifferent.

For nearly four years you have had an Administration which instead of twirling its thumbs has rolled up its sleeves. We will keep our sleeves rolled up.

We had to struggle with the old enemies of peace—business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering. They had begun to consider the Government of the United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs. We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob.

Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.[27]

Results

[edit]

Roosevelt won in a landslide, carrying 46 of the 48 states and bringing in many additional Democratic members of Congress. After Lyndon B. Johnson's 61.05% share of the popular vote in 1964, Roosevelt's 60.8% is the second-largest percentage in U.S. history (since 1824, when the vast majority of or all states have had a popular vote), and his 98.49% of the electoral vote is the highest in two-party competition.

The Republican Party saw its total in the United States House of Representatives reduced to 88 seats and in the United States Senate to 16 seats in their respective elections and only won four governorships in the 1936 elections.[28] Roosevelt won the largest number of electoral votes ever recorded at that time, and has so far only been surpassed by Ronald Reagan in 1984, when seven more electoral votes were available to contest. Garner also won the highest percentage of the electoral vote of any vice president.

Landon won only eight electoral votes, tying William Howard Taft's total in his unsuccessful re-election campaign of 1912, which as of 2024, is the lowest electoral vote total for a major-party candidate.

Roosevelt's net vote totals in the twelve largest cities increased from 1,791,000 votes in the 1932 election to 3,479,000 votes which was the highest for any presidential candidate from 1920 to 1948. Philadelphia and Columbus, Ohio, which had voted for Hoover in the 1932 election, voted for Roosevelt in the 1936 election. Although the majority of black voters had been Republican in the 1932 election Roosevelt won two-thirds of black voters in the 1936 election.[28]

Norman Thomas, who had received 884,885 votes in the 1932 election saw his totals decrease to 187,910.[28]

The eleven states of the former Confederacy provided 4.78% of Landon's votes, with him taking 19.09% of the vote in that region.[29]

This was the last Democratic landslide in the West, as Democrats won every state except Kansas (Landon's home state) by more than 10%. West of the Great Plains States, Roosevelt only lost eight counties. Since 1936, only Richard Nixon in 1972 (winning all but 19 counties)[30] and Ronald Reagan in 1980 (winning all but twenty counties) have even approached such a disproportionate ratio.

Of the 3,095 counties, parishes and independent cities making returns, Roosevelt won in 2,634 (85 percent) while Landon carried 461 (15 percent); this was one of the few measures by which Landon's campaign was more successful than Hoover's had been four years prior, with Landon winning 87 more counties than Hoover did, albeit mostly in less populous parts of the country. Democrats also expanded their majorities in Congress, winning control of over three-quarters of the seats in each house.

The election saw the consolidation of the New Deal coalition; while the Democrats lost some of their traditional allies in big business, high-income voters, businessmen and professionals, they were replaced by groups such as organized labor and African Americans, the latter of whom voted Democratic for the first time since the Civil War,[citation needed] and made major gains among the poor and other minorities. Roosevelt won 86 percent of the Jewish vote, 81 percent of the Catholics, 80 percent of union members, 76 percent of Southerners, 76 percent of Blacks in northern cities, and 75 percent of people on relief. Roosevelt also carried 102 of the nation's 106 cities with a population of 100,000 or more.[31]

Some political pundits predicted the Republicans, whom many voters blamed for the Great Depression, would soon become an extinct political party.[32] However, the Republicans would make a strong comeback in the 1938 congressional elections, and while they would remain a potent force in Congress,[32] they were not able to regain control of the House or the Senate until 1946, and would not regain the presidency until 1952.

The Electoral College results, in which Landon only won Maine and Vermont, inspired Democratic Party chairman James Farley—who had in fact declared during the campaign that Roosevelt would lose only these two states[22]—to amend the then-conventional political wisdom of "As Maine goes, so goes the nation" into "As Maine goes, so goes Vermont." In fact, since then, the states of Vermont and Maine voted for the same candidate in every election except the 1968 presidential election. Additionally, a prankster posted a sign on Vermont's border with New Hampshire the day after the 1936 election, reading, "You are now leaving the United States."[22]

This was the last election in which Indiana, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota would vote Democratic until 1964. Of these states, only Indiana would vote Democratic again after 1964 (for Barack Obama in 2008), making this the penultimate time a Democrat won any of the Great Plains states.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Franklin D. Roosevelt (incumbent) | Democratic | New York | 27,752,648 | 60.80% | 523 | John Nance Garner (incumbent) | Texas | 523 |

| Alf Landon | Republican | Kansas | 16,681,862 | 36.54% | 8 | Frank Knox | Illinois | 8 |

| William Lemke | Union | North Dakota | 892,378 | 1.95% | 0 | Thomas C. O'Brien | Massachusetts | 0 |

| Norman Thomas | Socialist | New York | 187,910 | 0.41% | 0 | George A. Nelson | Wisconsin | 0 |

| Earl Browder | Communist | Kansas | 79,315 | 0.17% | 0 | James W. Ford | New York | 0 |

| D. Leigh Colvin | Prohibition | New York | 37,646 | 0.08% | 0 | Claude A. Watson | California | 0 |

| John W. Aiken | Socialist Labor | Connecticut | 12,799 | 0.03% | 0 | Emil F. Teichert | New York | 0 |

| Other | 3,141 | 0.00% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 45,647,699 | 100% | 531 | 531 | ||||

| Needed to win | 266 | 266 | ||||||

Source (popular vote): Leip, David. "1936 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

Source (electoral vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

Geography of results

[edit]

-

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

[edit]-

Presidential election results by county

-

Democratic presidential election results by county

-

Republican presidential election results by county

-

"Other" presidential election results by county

-

American Labor presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of American Labor presidential election results by county

Results by state

[edit]Source:[33]

| States/districts won by Roosevelt/Garner |

| States/districts won by Landon/Knox |

| Franklin D. Roosevelt Democratic |

Alfred Landon Republican |

William Lemke Union |

Norman Thomas Socialist |

Other | Margin | Margin Swing[b] |

State total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | % | # | |

| Alabama | 11 | 238,136 | 86.38 | 11 | 35,358 | 12.82 | - | 551 | 0.20 | - | 242 | 0.09 | - | 1,397 | 0.51 | - | 202,838 | 73.56 | 2.95 | 275,244 | AL |

| Arizona | 3 | 86,722 | 69.85 | 3 | 33,433 | 26.93 | - | 3,307 | 2.66 | - | 317 | 0.26 | - | 384 | 0.31 | - | 53,289 | 42.92 | 6.42 | 124,163 | AZ |

| Arkansas | 9 | 146,765 | 81.80 | 9 | 32,039 | 17.86 | - | 4 | 0.00 | - | 446 | 0.25 | - | 169 | 0.09 | - | 114,726 | 63.94 | -9.12 | 179,423 | AR |

| California | 22 | 1,766,836 | 66.95 | 22 | 836,431 | 31.70 | - | - | - | - | 11,331 | 0.43 | - | 24,284 | 0.92 | - | 930,405 | 35.26 | 14.26 | 2,638,882 | CA |

| Colorado | 6 | 295,021 | 60.37 | 6 | 181,267 | 37.09 | - | 9,962 | 2.04 | - | 1,593 | 0.33 | - | 841 | 0.17 | - | 113,754 | 23.28 | 9.90 | 488,684 | CO |

| Connecticut | 8 | 382,129 | 55.32 | 8 | 278,685 | 40.35 | - | 21,805 | 3.16 | - | 5,683 | 0.82 | - | 2,421 | 0.35 | - | 103,444 | 14.98 | 16.12 | 690,723 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 69,702 | 54.62 | 3 | 57,236 | 44.85 | - | 442 | 0.35 | - | 172 | 0.13 | - | 51 | 0.04 | - | 12,466 | 9.77 | 12.21 | 127,603 | DE |

| Florida | 7 | 249,117 | 76.10 | 7 | 78,248 | 23.90 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 170,869 | 52.20 | 2.56 | 327,365 | FL |

| Georgia | 12 | 255,364 | 87.10 | 12 | 36,942 | 12.60 | - | 141 | 0.05 | - | 68 | 0.02 | - | 660 | 0.23 | - | 218,422 | 74.50 | -9.33 | 293,175 | GA |

| Idaho | 4 | 125,683 | 62.96 | 4 | 66,256 | 33.19 | - | 7,678 | 3.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 59,427 | 29.77 | 9.38 | 199,617 | ID |

| Illinois | 29 | 2,282,999 | 57.70 | 29 | 1,570,393 | 39.69 | - | 89,439 | 2.26 | - | 7,530 | 0.19 | - | 6,161 | 0.16 | - | 712,606 | 18.01 | 4.82 | 3,956,522 | IL |

| Indiana | 14 | 934,974 | 56.63 | 14 | 691,570 | 41.89 | - | 19,407 | 1.18 | - | 3,856 | 0.23 | - | 1,090 | 0.07 | - | 243,404 | 14.74 | 3.02 | 1,650,897 | IN |

| Iowa | 11 | 621,756 | 54.41 | 11 | 487,977 | 42.70 | - | 29,687 | 2.60 | - | 1,373 | 0.12 | - | 1,940 | 0.17 | - | 133,779 | 11.71 | -6.00 | 1,142,733 | IA |

| Kansas | 9 | 464,520 | 53.67 | 9 | 397,727 | 45.95 | - | 497 | 0.06 | - | 2,770 | 0.32 | - | - | - | - | 66,793 | 7.72 | -1.71 | 865,014 | KS |

| Kentucky | 11 | 541,944 | 58.51 | 11 | 369,702 | 39.92 | - | 12,501 | 1.35 | - | 632 | 0.07 | - | 1,424 | 0.15 | - | 172,242 | 18.60 | -0.31 | 926,203 | KY |

| Louisiana | 10 | 292,894 | 88.82 | 10 | 36,791 | 11.16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 93 | 0.00 | - | 256,103 | 77.66 | -8.11 | 329,778 | LA |

| Maine | 5 | 126,333 | 41.52 | - | 168,823 | 55.49 | 5 | 7,581 | 2.49 | - | 783 | 0.26 | - | 720 | 0.24 | - | -42,490 | -13.97 | -1.33 | 304,240 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 389,612 | 62.35 | 8 | 231,435 | 37.04 | - | - | - | - | 1,629 | 0.26 | - | 2,220 | 0.36 | - | 158,177 | 25.31 | -0.15 | 624,896 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 17 | 942,716 | 51.22 | 17 | 768,613 | 41.76 | - | 118,639 | 6.45 | - | 5,111 | 0.28 | - | 5,278 | 0.29 | - | 174,103 | 9.46 | 5.46 | 1,840,357 | MA |

| Michigan | 19 | 1,016,794 | 56.33 | 19 | 699,733 | 38.76 | - | 75,795 | 4.20 | - | 8,208 | 0.45 | - | 4,568 | 0.25 | - | 317,061 | 17.56 | 9.64 | 1,805,098 | MI |

| Minnesota | 11 | 698,811 | 61.84 | 11 | 350,461 | 31.01 | - | 74,296 | 6.58 | - | 2,872 | 0.25 | - | 3,535 | 0.31 | - | 348,350 | 30.83 | 7.21 | 1,129,975 | MN |

| Mississippi | 9 | 157,318 | 97.06 | 9 | 4,443 | 2.74 | - | - | - | - | 329 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | 152,875 | 94.31 | 1.87 | 162,090 | MS |

| Missouri | 15 | 1,111,043 | 60.76 | 15 | 697,891 | 38.16 | - | 14,630 | 0.80 | - | 3,454 | 0.19 | - | 1,617 | 0.09 | - | 413,152 | 22.59 | -6.03 | 1,828,635 | MO |

| Montana | 4 | 159,690 | 69.28 | 4 | 63,598 | 27.59 | - | 5,549 | 2.41 | - | 1,066 | 0.46 | - | 609 | 0.26 | - | 96,092 | 41.69 | 18.96 | 230,512 | MT |

| Nebraska | 7 | 347,445 | 57.14 | 7 | 247,731 | 40.74 | - | 12,847 | 2.11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 99,714 | 16.40 | -11.30 | 608,023 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 31,925 | 72.81 | 3 | 11,923 | 27.19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20,002 | 45.62 | 6.80 | 43,848 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 108,460 | 49.73 | 4 | 104,642 | 47.98 | - | 4,819 | 2.21 | - | - | - | - | 193 | 0.09 | - | 3,818 | 1.75 | 3.18 | 218,114 | NH |

| New Jersey | 16 | 1,083,850 | 59.54 | 16 | 720,322 | 39.57 | - | 9,407 | 0.52 | - | 3,931 | 0.22 | - | 2,927 | 0.16 | - | 364,128 | 19.97 | 18.07 | 1,820,437 | NJ |

| New Mexico | 3 | 106,037 | 62.69 | 3 | 61,727 | 36.50 | - | 924 | 0.55 | - | 343 | 0.20 | - | 105 | 0.06 | - | 44,310 | 26.20 | -0.76 | 169,176 | NM |

| New York | 47 | 3,293,222 | 58.85 | 47 | 2,180,670 | 38.97 | - | - | - | - | 86,897 | 1.55 | - | 35,609 | 0.64 | - | 1,112,552 | 19.88 | 7.15 | 5,596,398 | NY |

| North Carolina | 13 | 616,141 | 73.40 | 13 | 223,283 | 26.60 | - | 2 | 0.00 | - | 21 | 0.00 | - | 17 | 0.00 | - | 392,858 | 46.80 | 6.15 | 839,464 | NC |

| North Dakota | 4 | 163,148 | 59.60 | 4 | 72,751 | 26.58 | - | 36,708 | 13.41 | - | 552 | 0.20 | - | 557 | 0.20 | - | 90,397 | 33.03 | -8.55 | 273,716 | ND |

| Ohio | 26 | 1,747,140 | 57.99 | 26 | 1,127,855 | 37.44 | - | 132,212 | 4.39 | - | 117 | 0.00 | - | 5,265 | 0.17 | - | 619,285 | 20.56 | 17.71 | 3,012,589 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 11 | 501,069 | 66.83 | 11 | 245,122 | 32.69 | - | - | - | - | 2,221 | 0.30 | - | 1,328 | 0.18 | - | 255,947 | 34.14 | -12.45 | 749,740 | OK |

| Oregon | 5 | 266,733 | 64.42 | 5 | 122,706 | 29.64 | - | 21,831 | 5.27 | - | 2,143 | 0.52 | - | 608 | 0.15 | - | 144,027 | 34.79 | 13.68 | 414,021 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 36 | 2,353,987 | 56.88 | 36 | 1,690,200 | 40.84 | - | 67,468 | 1.63 | - | 14,599 | 0.35 | - | 12,172 | 0.29 | - | 663,787 | 16.04 | 21.55 | 4,138,426 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 165,238 | 53.10 | 4 | 125,031 | 40.18 | - | 19,569 | 6.29 | - | - | - | - | 1,340 | 0.43 | - | 40,207 | 12.92 | 1.15 | 311,178 | RI |

| South Carolina | 8 | 113,791 | 98.57 | 8 | 1,646 | 1.43 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 112,145 | 97.15 | 1.02 | 115,437 | SC |

| South Dakota | 4 | 160,137 | 54.02 | 4 | 125,977 | 42.49 | - | 10,338 | 3.49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 34,160 | 11.52 | -17.71 | 296,472 | SD |

| Tennessee | 11 | 328,083 | 68.85 | 11 | 146,520 | 30.75 | - | 296 | 0.06 | - | 686 | 0.14 | - | 953 | 0.20 | - | 181,563 | 38.10 | 4.09 | 476,538 | TN |

| Texas | 23 | 734,485 | 87.08 | 23 | 103,874 | 12.31 | - | 3,281 | 0.39 | - | 1,075 | 0.13 | - | 767 | 0.09 | - | 630,611 | 74.76 | -1.96 | 843,482 | TX |

| Utah | 4 | 150,246 | 69.34 | 4 | 64,555 | 29.79 | - | 1,121 | 0.52 | - | 432 | 0.20 | - | 323 | 0.15 | - | 85,691 | 39.55 | 24.08 | 216,677 | UT |

| Vermont | 3 | 62,124 | 43.24 | - | 81,023 | 56.39 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 542 | 0.38 | - | -18,899 | -13.15 | 3.43 | 143,689 | VT |

| Virginia | 11 | 234,980 | 70.23 | 11 | 98,336 | 29.39 | - | 233 | 0.07 | - | 313 | 0.09 | - | 728 | 0.22 | - | 136,644 | 40.84 | 2.46 | 334,590 | VA |

| Washington | 8 | 459,579 | 66.38 | 8 | 206,892 | 29.88 | - | 17,463 | 2.52 | - | 3,496 | 0.50 | - | 4,908 | 0.71 | - | 252,687 | 36.50 | 12.98 | 692,338 | WA |

| West Virginia | 8 | 502,582 | 60.56 | 8 | 325,358 | 39.20 | - | - | - | - | 832 | 0.10 | - | 1,173 | 0.14 | - | 177,224 | 21.35 | 11.35 | 829,945 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 802,984 | 63.80 | 12 | 380,828 | 30.26 | - | 60,297 | 4.79 | - | 10,626 | 0.84 | - | 3,825 | 0.30 | - | 422,156 | 33.54 | 1.28 | 1,258,560 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 62,624 | 60.58 | 3 | 38,739 | 37.47 | - | 1,653 | 1.60 | - | 200 | 0.19 | - | 166 | 0.16 | - | 23,885 | 23.10 | 7.85 | 103,382 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 531 | 27,752,648 | 60.80 | 523 | 16,681,862 | 36.54 | 8 | 892,378 | 1.95 | - | 187,910 | 0.41 | - | 132,901 | 0.29 | - | 11,070,786 | 24.25 | 6.49 | 45,647,699 | US |

States that flipped from Republican to Democratic

[edit]Close states

[edit]Margin of victory less than 5% (4 electoral votes):

- New Hampshire, 1.75% (3,818 votes)

Margin of victory greater than 5% but less than 10% (29 electoral votes):

- Kansas, 7.72% (66,793 votes)

- Massachusetts, 9.46% (174,103 votes)

- Delaware, 9.77% (12,466 votes)

Tipping point state:

- Ohio, 20.56% (619,285 votes)

Statistics

[edit]Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Issaquena County, Mississippi 100.00%

- Horry County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Lancaster County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Greensville County, Virginia 100.00%

- Edgefield County, South Carolina 99.92%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Jackson County, Kentucky 89.05%

- Johnson County, Tennessee 84.39%

- Owsley County, Kentucky 83.02%

- Leslie County, Kentucky 81.39%

- Avery County, North Carolina 77.98%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Other)

- Burke County, North Dakota 31.63%

- Sheridan County, North Dakota 28.88%

- Hettinger County, North Dakota 28.25%

- Mountrail County, North Dakota 25.73%

- Steele County, North Dakota 24.30%

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The book was published posthumously in 1935.[13]

- ^ Percentage point difference in margin from the 1932 election

References

[edit]- ^ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- ^ Paul Kleppner et al. The Evolution of American Electoral Systems pp 219–225.

- ^ Kalb, Deborah, ed. (2010). Guide to U.S. Elections. Washington, DC: CQ Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-1-60426-536-1.

- ^ "Borah and Nye want to form new national party. Washington, D.C., May 6. There have been new rumors that Senator Borah of Idaho and Senator Nye of North Dakota and other insurgent Republicans want to start a new National party with the purpose of unhorsing the present Republican National Committee. The leadership will fall to Senators William E. Borah and Gerald P. Nye caught as they were confering together at the Capitol today, 5/6/1937". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Kane, Harnett; Huey Long's Louisiana Hayride, p. 126. ISBN 1455606111

- ^ Hair, William Ivy; The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long; ISBN 080712124X

- ^ Carpenter, Ronald H.; Father Charles E. Coughlin: Surrogate Spokesman for the Disaffected; p. 62 ISBN 0-313-29040-7

- ^ Snyder (1975), p. 121.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, William E. (Fall 1985). "FDR And The Kingfish". American Heritage. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Snyder (1975), p. 122.

- ^ a b Snyder (1975), p. 125.

- ^ Snyder (1975), pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Brown, Francis (September 29, 1935). "Huey Long as Hero and as Demagogue; My First Days in the White House. By Huey Pierce Long. 146 pp. Harrisburg, Pa.: The Telegraph Press". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Sanson (2006), p. 274.

- ^ Kennedy (2005) [1999], pp. 239–40.

- ^ Hair (1996), p. 284.

- ^ a b Kennedy (2005) [1999], p. 240.

- ^ Snyder (1975), p. 128.

- ^ "FDR and the Kingfish". AMERICAN HERITAGE.

- ^ Kennedy (2005) [1999], p. 239.

- ^ a b c Kennedy (2005) [1999], p. 241.

- ^ a b c Derbyshire, Wyn; Dark Realities: America's Great Depression; p. 213 ISBN 1907444777

- ^ Bryson, Maurice C. 'The Literary Digest Poll: Making of a Statistical Myth' The American Statistician, 30 (4): November 1976.

- ^ Squire, Peverill (1988). "Why the 1936 Literary Digest Poll Failed". Public Opinion Quarterly. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Time, August 31, 1936

- ^ Time October 26, 1936

- ^ "Franklin Delano Roosevelt Madison Square Garden Speech (1936)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Paul (1974). Political Parties In American History, Volume 3, 1890-present. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- ^ Sherman 1973, p. 263.

- ^ Rich Exner, cleveland com (June 7, 2016). "1972 Ohio presidential election results; Richard Nixon defeats George McGovern". cleveland. Retrieved March 12, 2025.

- ^ Mary E. Stuckey (2015). Voting Deliberatively: FDR and the 1936 Presidential Campaign. Penn State UP. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-271-07192-3.

- ^ a b Gould, Lewis L.; The Republicans: A History of the Grand Old Party. ISBN 0199936625

- ^ a b "1936 Presidential General Election Data – National". Retrieved April 8, 2013.

Works cited

[edit]- Hair, William Ivy (1991). The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807141069.

- Sanson, Jerry P. (Summer 2006). ""What He Did and What He Promised to Do... ": Huey Long and the Horizons of Louisiana Politics". The Journal of Louisiana Historical. 47 (3): 261–276. JSTOR 4234200.

- Sherman, Richard (1973). The Republican Party and Black America From McKinley to Hoover 1896-1933. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0813904676.

- Snyder, Robert E. (Spring 1975). "Huey Long and the Presidential Election of 1936". The Journal of Louisiana Historical. 16 (2): 117–143. JSTOR 4231456.

Further reading

[edit]- Andersen, Kristi. The Creation of a Democratic Majority: 1928–1936 (1979), statistical

- Brown, Courtney. "Mass dynamics of US presidential competitions, 1928–1936." American Political Science Review 82.4 (1988): 1153–1181. online

- Burns, James MacGregor. Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox (1956)

- Campbell, James E. "Sources of the new deal realignment: The contributions of conversion and mobilization to partisan change." Western Political Quarterly 38.3 (1985): 357–376. online

- Fadely, James Philip. "Editors, Whistle Stops, and Elephants: the Presidential Campaign of 1936 in Indiana." Indiana Magazine of History 1989 85(2): 101–137. ISSN 0019-6673

- Harrell, James A. "Negro Leadership in the Election Year 1936." Journal of Southern History 34.4 (1968): 546–564. online

- Kennedy, Patrick D. "Chicago's Irish Americans and the Candidacies of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1932-1944." Illinois Historical Journal 88.4 (1995): 263–278. online

- Leuchtenburg, William E. "Election of 1936", in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., ed., A History of American Presidential Elections vol 3 (1971), analysis and primary documents

- McCoy, Donald. Landon of Kansas (1968)

- Nicolaides, Becky M. "Radio Electioneering in the American Presidential Campaigns of 1932 and 1936", Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, June 1988, Vol. 8 Issue 2, pp. 115–138

- Pietrusza, David Roosevelt Sweeps Nation: FDR’s 1936 Landslide and the Triumph of the Liberal Ideal (2022).

- Savage, Sean J. "The 1936-1944 Campaigns", in William D. Pederson, ed. A Companion to Franklin D. Roosevelt (2011) pp 96–113 online

- Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur M. The Politics of Upheaval (1960)

- Sheppard, Si. The Buying of the Presidency? Franklin D. Roosevelt, the New Deal, and the Election of 1936. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2014.

- Shover, John L. "The emergence of a two-party system in Republican Philadelphia, 1924-1936." Journal of American History 60.4 (1974): 985–1002. online

- Spencer, Thomas T. "'Labor is with Roosevelt:' The Pennsylvania Labor Non-Partisan League and the Election of 1936." Pennsylvania History 46.1 (1979): 3–16. online

Primary sources

[edit]- Cantril, Hadley and Mildred Strunk, eds.; Public Opinion, 1935–1946 (1951), massive compilation of many public opinion polls from USA

- Gallup, George H. ed. The Gallup Poll, Volume One 1935–1948 (1972) statistical reports on each poll

- Chester, Edward W A guide to political platforms (1977) online

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840-1964 (1965) online 1840-1956

External links

[edit]1936 United States presidential election

View on GrokipediaBackground and Context

Persistence of the Great Depression

The Great Depression persisted into 1936, with unemployment standing at 16.9 percent of the labor force, down from a peak of 24.9 percent in 1933 but far exceeding pre-Depression norms of around 5 percent.[6] [7] This elevated joblessness reflected incomplete recovery, as real GDP per adult remained substantially below trend levels established before 1929, with the economy still operating at roughly 27 percent below potential by 1939 and similar shortfalls in the preceding years.[8] Industrial production had rebounded from its 1933 low but reached only about 3 percent above 1929 levels by 1937, indicating sluggish output growth amid ongoing deflationary pressures and weak investment.[9] Economic hardship manifested in widespread poverty, with wage incomes for employed workers having fallen 42.5 percent from 1929 to 1933 and only partially recovering by 1936.[7] Farm sectors suffered from plummeting incomes and foreclosures, while urban areas grappled with breadlines and shantytowns, as documented in contemporaneous photographs of vacant storefronts and idle workers. Bank failures, though reduced after 1933 reforms, had eroded savings, and consumer confidence remained fragile, contributing to subdued demand.[7] Analyses attribute the Depression's duration to initial monetary contraction following the 1929 crash and subsequent policies that raised real wages above market-clearing levels and cartelized industries, impeding full employment restoration until wartime mobilization.[8] By the 1936 election, these conditions framed voter assessments of incumbent policies, with empirical data showing neither a return to prosperity nor alleviation of mass suffering despite partial gains in employment and production.Assessment of Roosevelt's First-Term Policies

Franklin D. Roosevelt's first term, from March 1933 to 1936, featured the initial implementation of New Deal policies aimed at addressing the Great Depression through banking reforms, relief programs, agricultural adjustments, and industrial regulations. These measures contributed to a partial economic recovery, with real GDP growing at annual rates of 10.8% in 1934, 8.9% in 1935, and 12.9% in 1936, following a contraction of 1.2% in 1933.[10] However, GDP per capita remained below pre-Depression levels, and the economy's output had not fully rebounded by the end of the term.[11] Unemployment rates declined from a peak of 24.9% in 1933 to 21.7% in 1934, 20.1% in 1935, and 16.9% in 1936, reflecting the impact of relief efforts like the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which provided jobs to millions.[12] Banking stability improved markedly after the Emergency Banking Act of March 1933 and the establishment of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) via the Glass-Steagall Act, halting widespread bank failures and panics that had plagued the early Depression years; failures dropped from thousands annually pre-1933 to fewer than 100 by 1936.[13] [14] Critics, including economists from the Chicago School and later monetarists, argued that policies such as the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, which imposed industry codes for wages and prices, reduced competition and prolonged recovery by distorting market signals and creating uncertainty for businesses; the NIRA was struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in May 1935.[15] [16] Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) provisions, which paid farmers to reduce production to raise prices, succeeded in boosting farm incomes but at the cost of destroying surplus crops and livestock amid widespread hunger, exacerbating inefficiencies without addressing root monetary contraction issues.[17] Overall, while New Deal spending provided short-term relief and demand stimulus, federal outlays rising to nearly 11% of GDP by 1939, many analysts contend it failed to achieve full employment or robust private-sector growth, with unemployment still exceeding 14% entering 1937 and a subsequent recession underscoring policy limitations.[18] [19]Political Landscape Entering 1936

As of early 1936, the United States remained mired in the Great Depression, with unemployment averaging 20.1% in 1935 and declining modestly to around 16.9% by the following year, reflecting partial recovery from the 1933 peak of 24.9% but still indicating widespread economic distress affecting over 8 million workers.[6][12] Gross national product had risen from $56 billion in 1933 to $73 billion in 1935, driven by federal spending under the New Deal, yet critics argued this growth masked structural weaknesses and relied on deficit financing that ballooned the national debt from $22.5 billion to $28.7 billion.[7] The agricultural and industrial sectors continued to suffer, with farm incomes stagnant and manufacturing output below 1929 levels, fostering public dependence on government relief programs like the Works Progress Administration, which employed 3.5 million by mid-1936.[20] Democrats held commanding majorities in Congress following the 1934 midterm elections, the first in which the president's party gained seats in both chambers since the Civil War, securing 322 House seats to Republicans' 103 and 69 Senate seats to 25.[21] This alignment enabled passage of Second New Deal measures, including the Social Security Act of 1935 and the Wagner Act affirming labor rights, which solidified urban, labor, and ethnic voting blocs for Franklin D. Roosevelt while alienating business interests.[22] Roosevelt's personal approval hovered near 61%, buoyed by perceived relief efforts amid crisis, though early polls like those from Fortune magazine showed divisions, with stronger support in the Northeast and urban areas than in rural Protestant regions.[23] The Republican Party, decimated by the 1932 landslide, entered 1936 fragmented and defensive, unified primarily in opposition to New Deal expansions viewed as fiscally irresponsible and constitutionally overreaching, particularly after Supreme Court invalidations of programs like the National Recovery Administration in 1935.[24] Party leaders criticized deficit spending exceeding $30 billion cumulatively and warned of creeping socialism, appealing to fiscal conservatives and small-government advocates, but lacked a clear frontrunner, with figures like Kansas Governor Alf Landon emerging as pragmatic alternatives emphasizing state-led recovery over federal intervention.[25] Third-party challenges, such as those from Father Coughlin's radio demagoguery or the remnants of Huey Long's Share Our Wealth movement (disrupted by his 1935 assassination), hinted at populist discontent but posed limited structural threats given Democratic dominance.[26] Overall, the landscape favored Roosevelt's renomination and positioned the election as a referendum on sustained federal activism versus Republican calls for retrenchment.Nominations Process

Democratic Party Nomination

Incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought renomination at the Democratic National Convention held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from June 23 to 27, 1936.[27] Roosevelt faced negligible opposition in the preceding primaries, which ran from March 10 to May 19, 1936, in states including New Jersey, Maryland, and California, where he amassed delegate support without viable alternatives contesting his leadership.[28] His administration's New Deal programs had contributed to measurable economic gains, including reduced unemployment from 25% in 1933 to approximately 17% by 1936, bolstering party loyalty among delegates amid ongoing Depression-era challenges.[29] At the convention, delegates voted overwhelmingly to nominate Roosevelt on the first ballot, reflecting his unchallenged dominance within the party.[28] The assembly also abolished the longstanding two-thirds majority rule for nominations, replacing it with a simple majority requirement to streamline future processes and consolidate power behind the incumbent.[28] Vice President John Nance Garner was similarly renominated without contest, securing unity on the ticket despite emerging tensions over policy directions like court-packing proposals that would later surface.[30] Roosevelt delivered his acceptance speech via radio from Hyde Park, New York, on June 27, emphasizing the persistence of recovery efforts against Republican critiques and framing the election as a defense of democratic governance against economic peril.[31] Critics like former presidential nominee Al Smith voiced dissent through the American Liberty League, decrying New Deal expansions as veering toward socialism, but this opposition failed to translate into a formal convention challenge or delegate defection.[32] The nomination underscored the party's alignment behind Roosevelt's empirical focus on federal intervention to address causal factors of the Great Depression, such as banking instability and industrial collapse, prioritizing data-driven stabilization over ideological purity tests.[27]Republican Party Nomination

The Republican National Convention assembled from June 9 to 12, 1936, at the Public Auditorium in Cleveland, Ohio, to select the party's presidential and vice-presidential nominees.[33] Delegates nominated Kansas Governor Alf Landon for president on the first ballot conducted on June 11.[33] Landon, who had entered the race relatively late, positioned himself as a pragmatic executive with a record of fiscal conservatism, having balanced Kansas's budget amid the ongoing economic downturn.[34] Prior to the convention, the Republican primaries, held in select states from March to May, featured contests among candidates including Senator William E. Borah of Idaho and Chicago publisher Frank Knox, though these contests influenced delegate preferences rather than binding the convention outcome.[35] Borah, a progressive isolationist, mounted a challenge emphasizing opposition to the New Deal, while Knox withdrew his candidacy before the convention to endorse Landon.[35] Other prominent Republicans, such as former President Herbert Hoover and Senator Charles L. McNary, declined to pursue the nomination actively.[36] Landon formally accepted the nomination on July 23, 1936, in Topeka, Kansas, via an address pledging adherence to the Republican platform's principles of limited government and economic recovery without expansive federal intervention.[37] The convention then selected Knox as the vice-presidential nominee on June 12, completing the ticket as a balance of Midwestern appeal and newspaper influence.[33] This selection reflected the party's strategy to unify moderate and conservative factions against incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt.Minor and Third-Party Nominations

The Socialist Party of America held its national convention in Cleveland, Ohio, from May 25 to June 3, 1936, where it nominated Norman Mattoon Thomas, a Presbyterian minister and social reformer, as its presidential candidate for the fourth consecutive time. Thomas, who had garnered 884,781 votes (7.0 percent) in 1932, campaigned on a platform calling for nationalization of key industries, unemployment insurance, and public works to address the Depression's persistence, criticizing both major parties for insufficient radicalism.[38] The party's vice-presidential nominee was George Nelson, a labor organizer. The Union Party, a short-lived coalition formed in 1936 by anti-New Deal figures including radio priest Charles Coughlin and publisher Gerald L. K. Smith, nominated North Dakota Congressman William Lemke as its presidential candidate following his public announcement on June 19, 1936. The party's formal convention, held August 15–17 in Cleveland, Ohio, endorsed Lemke, a Republican-turned-independent known for the Frazier-Lemke Farm Bankruptcy Act, on a platform opposing Roosevelt's policies in favor of monetary reform and farm relief; Thomas C. O'Brien, a Boston lawyer, was selected as vice-presidential nominee.[39] The Communist Party USA nominated Earl Browder, its general secretary, and James W. Ford, a Harlem organizer and the first African American on a U.S. presidential ticket, by acclamation at a convention on June 29, 1936. Browder, a Kansas native and former labor activist with ties to Soviet Comintern directives, advocated a "united front" supporting Roosevelt's reelection while pushing for worker councils, anti-fascist measures, and wealth redistribution, reflecting the party's shift under Popular Front strategy.[40][41] The Prohibition Party nominated Herman P. Faris, a Colorado Springs businessman and former party treasurer, for president at its convention in Niagara Falls, New York, on July 8, 1936; Claude A. Watson, a California attorney, was the vice-presidential choice. The platform emphasized repeal of the 21st Amendment's effects, moral reform, and opposition to both major parties' handling of liquor interests and economic issues, though Faris died on March 20, 1936, prior to the convention, leading to posthumous listing in some states.[42] The Socialist Labor Party nominated John W. Aiken, a Massachusetts machinist, as its presidential candidate, continuing the party's orthodox Marxist stance against reformism and favoring industrial unionism and worker expropriation of production. Aiken, who had run previously, paired with vice-presidential nominee Emil Teofilo Parpala.[43]Campaign Strategies and Issues

Core Campaign Issues: Economy and New Deal

The economy remained a central focus of the 1936 presidential campaign, with the ongoing effects of the Great Depression underscoring debates over recovery strategies. By 1936, gross national product had risen to approximately $82 billion from a low of $56 billion in 1933, reflecting annual growth rates of around 8 percent in both 1935 and 1936, yet it remained well below the 1929 peak of $104 billion. Unemployment had declined to 16.9 percent from 24.9 percent at the Depression's nadir in 1933, but millions remained jobless amid persistent industrial underutilization and agricultural distress.[10][44][12][7] President Franklin D. Roosevelt positioned the New Deal as the indispensable mechanism for mitigating the crisis, emphasizing its relief efforts, regulatory reforms, and public works that employed over 8.5 million people through programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which funded infrastructure, arts, and conservation projects. In his October 31, 1936, campaign address at Madison Square Garden, Roosevelt defended the Second New Deal initiatives—including the Social Security Act, National Labor Relations Act, and Wealth Tax Act—as extensions of proven recovery measures that had restored confidence and countered business opposition. He argued these policies preserved capitalism by addressing market failures, rejecting Republican characterizations of them as excessive intervention.[45][45] Republican nominee Alf Landon and the party platform, however, assailed the New Deal as unconstitutional overreach that centralized power in Washington, violated states' rights, and stifled private enterprise through regulations and uncertainty. The platform contended that New Deal spending—resulting in massive deficits and "frightful waste" for partisan ends—had prolonged the Depression by breeding fear among investors, discouraging job creation, and risking national bankruptcy, rather than fostering genuine recovery. Landon specifically criticized the Social Security Act as unworkable and fraudulent, claiming its payroll taxes funded a illusory reserve while excluding most workers from benefits, and pledged to retain only constitutionally sound elements while prioritizing balanced budgets and reduced federal intrusion.[24][46][24] The contest thus hinged on causal attributions for partial recovery: Roosevelt attributed gains to federal activism that provided direct relief and stabilized banking and agriculture, while Landon argued market-driven incentives, unhindered by bureaucratic expansion, would accelerate true prosperity without eroding liberties or fiscal discipline. Empirical data showed deficit-financed spending correlating with output growth, yet critics highlighted persistent high unemployment and a subsequent 1937-1938 recession—partly linked to tightened fiscal and monetary policies—as evidence of New Deal vulnerabilities, including policy-induced uncertainty.[24]Franklin D. Roosevelt's Campaign Tactics

Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1936 campaign emphasized the successes of his New Deal programs while portraying the election as a defense of democratic progress against entrenched economic interests. Rather than proposing expansive new policies that might alienate conservative Democrats, Roosevelt focused on consolidating support among urban workers, labor unions, farmers, and emerging minority voter blocs, framing Republican challenger Alf Landon as an extension of the pre-1933 policies blamed for prolonging the Great Depression. This approach positioned the contest as a referendum on recovery efforts, with Roosevelt leveraging his incumbency to highlight measurable gains like reduced unemployment from 25% in 1933 to approximately 17% by 1936, without delving into unresolved fiscal challenges or program costs.[29] A core tactic was Roosevelt's use of direct, emotive rhetoric to rally the "forgotten man" against what he termed "economic royalists"—business and financial elites accused of prioritizing monopoly power over public welfare. In his June 27, 1936, acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, he declared these opponents complained not of threats to American institutions but of challenges to their undue influence, stating, "These economic royalists complain that we seek to overthrow the institutions of America. What they really complain of is that we seek to take away their power." This class-inflected language, echoed in subsequent addresses, aimed to unify diverse coalition elements by invoking a narrative of restoration versus regression, while relishing opposition as validation of his reforms.[31][29] Roosevelt supplemented public rallies with radio broadcasts to bypass traditional media filters and foster personal connection. He delivered targeted fireside chats, such as the September 6, 1936, address urging farmers and laborers to recognize their mutual dependence amid economic interdependence, reminding listeners of New Deal aid like Agricultural Adjustment Administration payments and Works Progress Administration jobs that sustained rural and urban households alike. These informal evening talks, broadcast nationally, reinforced themes of shared sacrifice and government responsiveness, drawing on Roosevelt's reassuring baritone to build trust in an era of widespread radio ownership exceeding 80% of households.[47] The campaign culminated in high-energy personal appearances, including the October 31, 1936, Madison Square Garden speech in New York City, where Roosevelt defiantly welcomed unified elite opposition, proclaiming, "Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred." This eve-of-election address defended legislative achievements like the Social Security Act—supported by only 77 House Republicans and 15 Senators—and critiqued GOP deceit in worker outreach, energizing urban crowds while signaling unyielding commitment to the underprivileged. Complementing these efforts, Democratic organizers deployed speakers' bureaus and local mobilization drives to convert undecided voters and boost turnout among relief recipients, capitalizing on party infrastructure built during Roosevelt's first term.[48][49]Alf Landon's Republican Challenge

Alf Landon, the Republican nominee and Governor of Kansas since 1933, mounted his challenge by highlighting his success in balancing the state budget amid the Great Depression, a feat achieved through spending cuts and efficient administration without resorting to heavy federal aid.[36] This record positioned him as a proponent of fiscal conservatism, contrasting sharply with the federal government's mounting deficits under the New Deal.[50] In his acceptance speech on July 23, 1936, in Topeka, Landon critiqued the New Deal's policies as hasty and poorly coordinated, arguing they imposed excessive federal control, disrupted agriculture through measures like the Agricultural Adjustment Act, and failed to deliver lasting reductions in unemployment, which remained comparable to 1933 levels.[37] He pledged to free American enterprise from bureaucratic overreach, excessive taxation, and monetary instability, while enforcing antitrust laws to curb monopolies and promoting soil conservation to support family farms with market-based incentives rather than rigid controls.[37] Landon's platform emphasized restoring economic confidence through reduced government waste, lower debts, and tax relief to stimulate private investment and consumer demand, rejecting prolonged dependency on relief programs.[37] He advocated preserving the constitutional balance between federal and state powers, limiting executive authority, and ensuring policy changes arose from democratic processes rather than centralized fiat.[37] A focal point of his critique was the Social Security Act of 1935, which Landon opposed for imposing payroll taxes starting at 2% of wages (rising to 6%), shared between employers and employees but often passed onto workers via higher prices or reduced wages—the largest tax increase in U.S. history at the time.[51] He warned that these funds could be diverted to cover current deficits or extravagances, leaving future pensioners with mere IOUs, and highlighted inequities where some workers paid into the system without comparable benefits available under state plans.[51] Landon called for amendments to make the program effective without political exploitation, framing it as part of a broader economic recovery strategy over unchecked expansion.[37] [51] Landon's campaign strategy relied on targeted speeches and radio addresses emphasizing policy differences, with limited personal travel compared to Roosevelt's vigorous tour, aiming to appeal to moderates and business interests disillusioned by New Deal regulations while avoiding inflammatory rhetoric against the president.[52] This restrained approach sought to portray Republicans as pragmatic reformers capable of delivering security and jobs through efficiency and decentralization, rather than portraying the contest as ideological warfare.[37]Role of Polling, Media, and Public Opinion

The 1936 election marked a pivotal moment in the history of public opinion polling, highlighting the contrast between unscientific straw polls and emerging scientific methods. The Literary Digest, a prominent magazine, conducted a massive survey by mailing ballots to approximately 10 million subscribers derived from telephone directories and automobile registration lists, receiving about 2.4 million responses that projected Republican candidate Alf Landon to win 57% of the popular vote and 370 electoral votes.[53][54] This prediction proved disastrously inaccurate, as incumbent Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt secured 62.2% of the popular vote and 523 electoral votes, with the Digest's error stemming primarily from sampling bias: its lists overrepresented wealthier, urban Republicans who owned phones and cars amid the Great Depression, when such assets correlated with opposition to New Deal policies, compounded by a low response rate of around 24% that amplified non-response bias among pro-Landon respondents.[55][56] In contrast, George Gallup's American Institute of Public Opinion employed quota sampling to approximate the electorate's demographics, correctly forecasting Roosevelt's victory with 56% of the popular vote within its reported margin of error, demonstrating the superiority of probability-based techniques and contributing to the Digest's bankruptcy shortly thereafter.[54][57] Media coverage heavily favored Landon, with the majority of major newspapers endorsing the Republican despite Roosevelt's popularity. An analysis of endorsements revealed that out of approximately 1,900 daily newspapers, only about 12% supported Roosevelt, including influential anti-New Deal outlets like the Chicago Tribune, owned by Robert R. McCormick, which ran aggressive campaigns portraying Roosevelt's policies as socialist threats; McCormick personally donated significantly to Landon's effort.[58][59] Radio broadcasting, however, provided Roosevelt a countervailing platform, as his fireside chats—totaling over 250 broadcasts by 1936—allowed direct appeals to listeners on economic recovery and relief programs, bypassing print media filters and resonating with a broadening audience amid rising radio ownership.[60] Figures like Father Charles Coughlin, whose radio show reached tens of millions, initially supported Roosevelt but shifted to third-party candidate William Lemke, yet empirical studies indicate Coughlin's anti-Roosevelt rhetoric had limited sway in altering vote outcomes due to geographic and demographic constraints on his audience.[61] Public opinion, as captured by nascent scientific polls, overwhelmingly favored Roosevelt, reflecting sustained support for New Deal initiatives amid partial economic rebound from the Depression's nadir. Gallup surveys throughout 1936 consistently showed Roosevelt leading by wide margins, with approval tied to perceptions of unemployment reduction from 25% in 1933 to around 17% by election time and programs like Social Security bolstering lower-income voters; Fortune magazine's post-election analysis noted Roosevelt's personal popularity exceeded even his 1936 margins in subsequent surveys, underscoring voter prioritization of relief over elite media critiques.[62] This disconnect between print media sentiment and grassroots opinion highlighted causal factors like direct policy benefits outweighing institutional opposition, with turnout reaching 61%—higher than 1932—driven by Democratic mobilization among urban laborers and farmers.[63]Election Results and Geography

National Vote Tallies and Electoral College

Franklin D. Roosevelt secured a resounding victory in the popular vote, receiving 27,752,648 ballots, which constituted 60.8% of the total cast, while Alf Landon tallied 16,681,913 votes, or 36.5%.[2] Third-party candidates, including Union Party nominee William Lemke, collectively garnered approximately 1.2 million votes, accounting for the remaining share.[3] Voter turnout reached 56.9% of the voting-age population, reflecting sustained public engagement amid ongoing economic recovery efforts.[2] In the Electoral College, Roosevelt amassed 523 votes, surpassing the 266 needed for a majority and marking the largest margin in American history to that date, as Landon won just 8 votes from Maine and Vermont.[1] This outcome underscored Roosevelt's dominance across nearly all regions, with Landon prevailing only in those two northeastern states, prompting the wry observation that "As Maine goes, so goes Vermont."[2] The following table summarizes the national results for the major tickets:| Party | Presidential Candidate | Vice Presidential Candidate | Popular Vote | Percentage | Electoral Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Franklin D. Roosevelt | John Nance Garner | 27,752,648 | 60.8% | 523 |

| Republican | Alf Landon | Frank Knox | 16,681,913 | 36.5% | 8 |

| Union | William Lemke | Thomas C. O'Brian | 892,378 | 2.0% | 0 |

| Socialist | Norman Thomas | George Nelson | 116,959 | 0.3% | 0 |

| Other | Various | Various | 202,799 | 0.4% | 0 |

State-Level Outcomes and Flips

Franklin D. Roosevelt secured the electoral votes from 46 states in the 1936 presidential election, leaving Alf Landon with victories only in Maine and Vermont for a total of 8 electoral votes out of 531.[1][64] This outcome represented a near-total consolidation of states under Democratic control, with Roosevelt capturing every state in the Solid South, the West Coast, and the industrial Midwest and Northeast, except the two New England outliers.[65] Compared to the 1932 election, where Republican incumbent Herbert Hoover carried six states, four of those—Connecticut, Delaware, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania—flipped to Roosevelt, contributing an additional 51 electoral votes to his tally.[65] Maine and Vermont held firm for the Republicans, preserving their status as regional exceptions amid widespread support for New Deal policies.[64] No states switched from Democratic to Republican control, underscoring the absence of backlash against Roosevelt's administration in previously supportive areas.[65] The flips were marked by decisive popular vote margins for Roosevelt, though New Hampshire proved the narrowest among them at 49.73% to Landon's 47.98%.[66] In Pennsylvania, the largest prize, Roosevelt garnered 56.88% against 41.94%.[67] Delaware and Connecticut also delivered comfortable wins at 54.62% and 55.32%, respectively, reflecting shifts in voter sentiment driven by economic recovery perceptions.[68][66]| Flipped State | Electoral Votes | 1932 Winner | 1936 Roosevelt % | 1936 Landon % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 8 | Hoover (R) | 55.32 | 41.22 |

| Delaware | 3 | Hoover (R) | 54.62 | 41.95 |

| New Hampshire | 4 | Hoover (R) | 49.73 | 47.98 |

| Pennsylvania | 36 | Hoover (R) | 56.88 | 41.94 |