Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

VSEPR theory

View on Wikipedia

Valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory (/ˈvɛspər, vəˈsɛpər/ VESP-ər,[1]: 410 və-SEP-ər[2]) is a model used in chemistry to predict the geometry of individual molecules from the number of electron pairs surrounding their central atoms.[3] It is also named the Gillespie-Nyholm theory after its two main developers, Ronald Gillespie and Ronald Nyholm but it is also called the Sidgwick-Powell theory after earlier work by Nevil Sidgwick and Herbert Marcus Powell.

The premise of VSEPR is that the valence electron pairs surrounding an atom tend to repel each other. The greater the repulsion, the higher in energy (less stable) the molecule is. Therefore, the VSEPR-predicted molecular geometry of a molecule is the one that has as little of this repulsion as possible. Gillespie has emphasized that the electron-electron repulsion due to the Pauli exclusion principle is more important in determining molecular geometry than the electrostatic repulsion.[4]

The insights of VSEPR theory are derived from topological analysis of the electron density of molecules. Such quantum chemical topology (QCT) methods include the electron localization function (ELF) and the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (AIM or QTAIM).[4][5]

History

[edit]The idea of a correlation between molecular geometry and number of valence electron pairs (both shared and unshared pairs) was originally proposed in 1939 by Ryutaro Tsuchida in Japan,[6] and was independently presented in a Bakerian Lecture in 1940 by Nevil Sidgwick and Herbert Powell of the University of Oxford.[7] In 1957, Ronald Gillespie and Ronald Sydney Nyholm of University College London refined this concept into a more detailed theory, capable of choosing between various alternative geometries.[8][9]

Overview

[edit]VSEPR theory is used to predict the arrangement of electron pairs around central atoms in molecules, especially simple and symmetric molecules. A central atom is defined in this theory as an atom which is bonded to two or more other atoms, while a terminal atom is bonded to only one other atom.[1]: 398 For example, in the molecule methyl isocyanate (H3C-N=C=O), the two carbons and one nitrogen are central atoms, and the three hydrogens and one oxygen are terminal atoms.[1]: 416 The geometry of the central atoms and their non-bonding electron pairs in turn determine the geometry of the larger whole molecule.

The number of electron pairs in the valence shell of a central atom is determined after drawing the Lewis structure of the molecule, and expanding it to show all bonding groups and lone pairs of electrons.[1]: 410–417 In VSEPR theory, a double bond or triple bond is treated as a single bonding group.[1] The sum of the number of atoms bonded to a central atom and the number of lone pairs formed by its nonbonding valence electrons is known as the central atom's steric number.

The electron pairs (or groups if multiple bonds are present) are assumed to lie on the surface of a sphere centered on the central atom and tend to occupy positions that minimize their mutual repulsions by maximizing the distance between them.[1]: 410–417 [10] The number of electron pairs (or groups), therefore, determines the overall geometry that they will adopt. For example, when there are two electron pairs surrounding the central atom, their mutual repulsion is minimal when they lie at opposite poles of the sphere. Therefore, the central atom is predicted to adopt a linear geometry. If there are 3 electron pairs surrounding the central atom, their repulsion is minimized by placing them at the vertices of an equilateral triangle centered on the atom. Therefore, the predicted geometry is trigonal. Likewise, for 4 electron pairs, the optimal arrangement is tetrahedral.[1]: 410–417

As a tool in predicting the geometry adopted with a given number of electron pairs, an often used physical demonstration of the principle of minimal electron pair repulsion utilizes inflated balloons. Through handling, balloons acquire a slight surface electrostatic charge that results in the adoption of roughly the same geometries when they are tied together at their stems as the corresponding number of electron pairs. For example, five balloons tied together adopt the trigonal bipyramidal geometry, just as do the five bonding pairs of a PCl5 molecule.

Steric number

[edit]

The steric number of a central atom in a molecule is the number of atoms bonded to that central atom, called its coordination number, plus the number of lone pairs of valence electrons on the central atom.[11] In the molecule SF4, for example, the central sulfur atom has four ligands; the coordination number of sulfur is four. In addition to the four ligands, sulfur also has one lone pair in this molecule. Thus, the steric number is 4 + 1 = 5.

Degree of repulsion

[edit]The overall geometry is further refined by distinguishing between bonding and nonbonding electron pairs. The bonding electron pair shared in a sigma bond with an adjacent atom lies further from the central atom than a nonbonding (lone) pair of that atom, which is held close to its positively charged nucleus. VSEPR theory therefore views repulsion by the lone pair to be greater than the repulsion by a bonding pair. As such, when a molecule has 2 interactions with different degrees of repulsion, VSEPR theory predicts the structure where lone pairs occupy positions that allow them to experience less repulsion. Lone pair–lone pair (lp–lp) repulsions are considered stronger than lone pair–bonding pair (lp–bp) repulsions, which in turn are considered stronger than bonding pair–bonding pair (bp–bp) repulsions, distinctions that then guide decisions about overall geometry when 2 or more non-equivalent positions are possible.[1]: 410–417 For instance, when 5 valence electron pairs surround a central atom, they adopt a trigonal bipyramidal molecular geometry with two collinear axial positions and three equatorial positions. An electron pair in an axial position has three close equatorial neighbors only 90° away and a fourth much farther at 180°, while an equatorial electron pair has only two adjacent pairs at 90° and two at 120°. The repulsion from the close neighbors at 90° is more important, so that the axial positions experience more repulsion than the equatorial positions; hence, when there are lone pairs, they tend to occupy equatorial positions as shown in the diagrams of the next section for steric number five.[10]

The difference between lone pairs and bonding pairs may also be used to rationalize deviations from idealized geometries. For example, the H2O molecule has four electron pairs in its valence shell: two lone pairs and two bond pairs. The four electron pairs are spread so as to point roughly towards the apices of a tetrahedron. However, the bond angle between the two O–H bonds is only 104.5°, rather than the 109.5° of a regular tetrahedron, because the two lone pairs (whose density or probability envelopes lie closer to the oxygen nucleus) exert a greater mutual repulsion than the two bond pairs.[1]: 410–417 [10]

A bond of higher bond order also exerts greater repulsion since the pi bond electrons contribute.[10] For example, in isobutylene, (H3C)2C=CH2, the H3C−C=C angle (124°) is larger than the H3C−C−CH3 angle (111.5°). However, in the carbonate ion, CO2−

3, all three C−O bonds are equivalent with angles of 120° due to resonance.

AXE method

[edit]The "AXE method" of electron counting is commonly used when applying the VSEPR theory. The electron pairs around a central atom are represented by a formula AXmEn, where A represents the central atom and always has an implied subscript one. Each X represents a ligand (an atom bonded to A). Each E represents a lone pair of electrons on the central atom.[1]: 410–417 The total number of X and E is known as the steric number. For example, in a molecule AX3E2, the atom A has a steric number of 5.

When the substituent (X) atoms are not all the same, the geometry is still approximately valid, but the bond angles may be slightly different from the ones where all the outside atoms are the same. For example, the double-bond carbons in alkenes like C2H4 are AX3E0, but the bond angles are not all exactly 120°. Likewise, SOCl2 is AX3E1, but because the X substituents are not identical, the X–A–X angles are not all equal.

Based on the steric number and distribution of Xs and Es, VSEPR theory makes the predictions in the following tables.

Main-group elements

[edit]For main-group elements, there are stereochemically active lone pairs E whose number can vary from 0 to 3. Note that the geometries are named according to the atomic positions only and not the electron arrangement. For example, the description of AX2E1 as a bent molecule means that the three atoms AX2 are not in one straight line, although the lone pair helps to determine the geometry.

| Steric number |

Molecular geometry[12] 0 lone pairs |

Molecular geometry[1]: 413–414 1 lone pair |

Molecular geometry[1]: 413–414 2 lone pairs |

Molecular geometry[1]: 413–414 3 lone pairs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | ||||

| 3 |  |

|

||

| 4 |  |

|

|

|

| 5 |  |

|

|

|

| 6 |  |

|

|

|

| 7 |  |

|

|

|

| 8 |

| Molecule type |

Molecular Shape[1]: 413–414 |

Electron Arrangement[1]: 413–414 including lone pairs, shown in yellow |

Geometry[1]: 413–414 excluding lone pairs |

Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AX2E0 | Linear | BeCl2,[3] CO2[10] | ||

| AX2E1 | Bent |

|

|

NO− 2,[3] SO2,[1]: 413–414 O3,[3] CCl2 |

| AX2E2 | Bent |

|

|

H2O,[1]: 413–414 OF2[13]: 448 |

| AX2E3 | Linear |

|

XeF2,[1]: 413–414 I− 3,[13]: 483 XeCl2 | |

| AX3E0 | Trigonal planar |

|

|

BF3,[1]: 413–414 CO2− 3,[13]: 368 CH 2O, NO− 3,[3] SO3[10] |

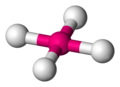

| AX3E1 | Trigonal pyramidal |

|

|

NH3,[1]: 413–414 PCl3[13]: 407 |

| AX3E2 | T-shaped |

|

|

ClF3,[1]: 413–414 BrF3[13]: 481 |

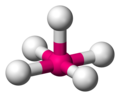

| AX4E0 | Tetrahedral |

|

|

CH4,[1]: 413–414 PO3− 4, SO2− 4,[10] ClO− 4,[3] XeO4[13]: 499 |

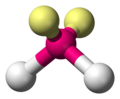

| AX4E1 | Seesaw or disphenoidal |

|

|

SF4[1]: 413–414 [13]: 45 |

| AX4E2 | Square planar |

|

|

XeF4[1]: 413–414 |

| AX5E0 | Trigonal bipyramidal |

|

|

PCl5,[1]: 413–414 PF5,[1]: 413–414 |

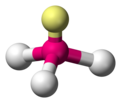

| AX5E1 | Square pyramidal |

|

|

ClF5,[13]: 481 BrF5,[1]: 413–414 XeOF4[10] |

| AX5E2 | Pentagonal planar |

|

|

XeF− 5[13]: 498 |

| AX6E0 | Octahedral |

|

|

SF6[1]: 413–414 |

| AX6E1 | Pentagonal pyramidal |

|

|

XeOF− 5,[14] IOF2− 5[14] |

| AX7E0 | Pentagonal bipyramidal[10] |

|

|

IF7[10] |

| AX8E0 | Square antiprismatic[10] |

|

|

IF− 8, XeF82- in (NO)2XeF8 |

Transition metals (Kepert model)

[edit]The lone pairs on transition metal atoms are usually stereochemically inactive, meaning that their presence does not change the molecular geometry. For example, the hexaaquo complexes M(H2O)6 are all octahedral for M = V3+, Mn3+, Co3+, Ni2+ and Zn2+, despite the fact that the electronic configurations of the central metal ion are d2, d4, d6, d8 and d10 respectively.[13]: 542 The Kepert model ignores all lone pairs on transition metal atoms, so that the geometry around all such atoms corresponds to the VSEPR geometry for AXn with 0 lone pairs E.[15][13]: 542 This is often written MLn, where M = metal and L = ligand. The Kepert model predicts the following geometries for coordination numbers of 2 through 9:

| Molecule type |

Shape | Geometry | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML2 | Linear | HgCl2[3] | |

| ML3 | Trigonal planar |

|

|

| ML4 | Tetrahedral |

|

NiCl2− 4 |

| ML5 | Trigonal bipyramidal |

|

Fe(CO) 5 |

| Square pyramidal |

|

MnCl52− | |

| ML6 | Octahedral |

|

WCl6[13]: 659 |

| ML7 | Pentagonal bipyramidal[10] |

|

ZrF3− 7 |

| Capped octahedral |

|

MoF− 7 | |

| Capped trigonal prismatic |

|

TaF2− 7 | |

| ML8 | Square antiprismatic[10] |

|

ReF− 8 |

| Dodecahedral |

|

Mo(CN)4− 8 | |

| Bicapped trigonal prismatic |

|

ZrF4− 8 | |

| ML9 | Tricapped trigonal prismatic |

|

ReH2− 9[13]: 254 |

| Capped square antiprismatic |

|

Examples

[edit]The methane molecule (CH4) is tetrahedral because there are four pairs of electrons. The four hydrogen atoms are positioned at the vertices of a tetrahedron, and the bond angle is cos−1(−1⁄3) ≈ 109° 28′.[16][17] This is referred to as an AX4 type of molecule. As mentioned above, A represents the central atom and X represents an outer atom.[1]: 410–417

The ammonia molecule (NH3) has three pairs of electrons involved in bonding, but there is a lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom.[1]: 392–393 It is not bonded with another atom; however, it influences the overall shape through repulsions. As in methane above, there are four regions of electron density. Therefore, the overall orientation of the regions of electron density is tetrahedral. On the other hand, there are only three outer atoms. This is referred to as an AX3E type molecule because the lone pair is represented by an E.[1]: 410–417 By definition, the molecular shape or geometry describes the geometric arrangement of the atomic nuclei only, which is trigonal-pyramidal for NH3.[1]: 410–417

Steric numbers of 7 or greater are possible, but are less common. The steric number of 7 occurs in iodine heptafluoride (IF7); the base geometry for a steric number of 7 is pentagonal bipyramidal.[10] The most common geometry for a steric number of 8 is a square antiprismatic geometry.[18]: 1165 Examples of this include the octacyanomolybdate (Mo(CN)4−

8) and octafluorozirconate (ZrF4−

8) anions.[18]: 1165 The nonahydridorhenate ion (ReH2−

9) in potassium nonahydridorhenate is a rare example of a compound with a steric number of 9, which has a tricapped trigonal prismatic geometry.[13]: 254 [18]

Steric numbers beyond 9 are very rare, and it is not clear what geometry is generally favoured.[19] Possible geometries for steric numbers of 10, 11, 12, or 14 are bicapped square antiprismatic (or bicapped dodecadeltahedral), octadecahedral, icosahedral, and bicapped hexagonal antiprismatic, respectively. No compounds with steric numbers this high involving monodentate ligands exist, and those involving multidentate ligands can often be analysed more simply as complexes with lower steric numbers when some multidentate ligands are treated as a unit.[18]: 1165, 1721

Exceptions

[edit]There are groups of compounds where VSEPR fails to predict the correct geometry.

Some AX2E0 molecules

[edit]The shapes of heavier Group 14 element alkyne analogues (RM≡MR, where M = Si, Ge, Sn or Pb) have been computed to be bent.[20][21][22]

Some AX2E2 molecules

[edit]One example of the AX2E2 geometry is molecular lithium oxide, Li2O, a linear rather than bent structure, which is ascribed to its bonds being essentially ionic and the strong lithium–lithium repulsion that results.[23] Another example is O(SiH3)2 with an Si–O–Si angle of 144.1°, which compares to the angles in Cl2O (110.9°), (CH3)2O (111.7°), and N(CH3)3 (110.9°).[24] Gillespie and Robinson rationalize the Si–O–Si bond angle based on the observed ability of a ligand's lone pair to most greatly repel other electron pairs when the ligand electronegativity is greater than or equal to that of the central atom.[24] In O(SiH3)2, the central atom is more electronegative, and the lone pairs are less localized and more weakly repulsive. The larger Si–O–Si bond angle results from this and strong ligand–ligand repulsion by the relatively large -SiH3 ligand.[24] Burford et al. showed through X-ray diffraction studies that Cl3Al–O–PCl3 has a linear Al–O–P bond angle and is therefore a non-VSEPR molecule.[25]

Some AX6E1 and AX8E1 molecules

[edit]

Some AX6E1 molecules, e.g. xenon hexafluoride (XeF6) and the Te(IV) and Bi(III) anions, TeCl2−

6, TeBr2−

6, BiCl3−

6, BiBr3−

6 and BiI3−

6, are octahedral, rather than pentagonal pyramids, and the lone pair does not affect the geometry to the degree predicted by VSEPR.[26] Similarly, the octafluoroxenate ion (XeF2−

8) in nitrosonium octafluoroxenate(VI)[13]: 498 [27][28] is a square antiprism with minimal distortion, despite having a lone pair. One rationalization is that steric crowding of the ligands allows little or no room for the non-bonding lone pair;[24] another rationalization is the inert-pair effect.[13]: 214

Square planar ML4 complexes

[edit]The Kepert model predicts that ML4 transition metal molecules are tetrahedral in shape, and it cannot explain the formation of square planar complexes.[13]: 542 The majority of such complexes exhibit a d8 configuration as for the tetrachloroplatinate (PtCl2−

4) ion. The explanation of the shape of square planar complexes involves electronic effects and requires the use of crystal field theory.[13]: 562–4

Complexes with strong d-contribution

[edit]

Some transition metal complexes with low d electron count have unusual geometries, which can be ascribed to d subshell bonding interaction.[29] Gillespie found that this interaction produces bonding pairs that also occupy the respective antipodal points (ligand opposed) of the sphere.[30][4] This phenomenon is an electronic effect resulting from the bilobed shape of the underlying sdx hybrid orbitals.[31][32] The repulsion of these bonding pairs leads to a different set of shapes.

| Molecule type | Shape | Geometry | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML2 | Bent |

|

TiO2[29] |

| ML3 | Trigonal pyramidal |

|

CrO3[33] |

| ML4 | Tetrahedral |

|

TiCl4[13]: 598–599 |

| ML5 | Square pyramidal |

|

Ta(CH3)5[34] |

| ML6 | C3v Trigonal prismatic |

|

W(CH3)6[35] |

The gas phase structures of the triatomic halides of the heavier members of group 2, (i.e., calcium, strontium and barium halides, MX2), are not linear as predicted but are bent, (approximate X–M–X angles: CaF2, 145°; SrF2, 120°; BaF2, 108°; SrCl2, 130°; BaCl2, 115°; BaBr2, 115°; BaI2, 105°).[36] It has been proposed by Gillespie that this is also caused by bonding interaction of the ligands with the d subshell of the metal atom, thus influencing the molecular geometry.[24][37]

Superheavy elements

[edit]Relativistic effects on the electron orbitals of superheavy elements is predicted to influence the molecular geometry of some compounds. For instance, the 6d5/2 electrons in nihonium play an unexpectedly strong role in bonding, so NhF3 should assume a T-shaped geometry, instead of a trigonal planar geometry like its lighter congener BF3.[38] In contrast, the extra stability of the 7p1/2 electrons in tennessine are predicted to make TsF3 trigonal planar, unlike the T-shaped geometry observed for IF3 and predicted for AtF3;[39] similarly, OgF4 should have a tetrahedral geometry, while XeF4 has a square planar geometry and RnF4 is predicted to have the same.[40]

Odd-electron molecules

[edit]The VSEPR theory can be extended to molecules with an odd number of electrons by treating the unpaired electron as a "half electron pair"—for example, Gillespie and Nyholm[8]: 364–365 suggested that the decrease in the bond angle in the series NO+

2 (180°), NO2 (134°), NO−

2 (115°) indicates that a given set of bonding electron pairs exert a weaker repulsion on a single non-bonding electron than on a pair of non-bonding electrons. In effect, they considered nitrogen dioxide as an AX2E0.5 molecule, with a geometry intermediate between NO+

2 and NO−

2. Similarly, chlorine dioxide (ClO2) is an AX2E1.5 molecule, with a geometry intermediate between ClO+

2 and ClO−

2.[citation needed]

Finally, the methyl radical (CH3) is predicted to be trigonal pyramidal like the methyl anion (CH−

3), but with a larger bond angle (as in the trigonal planar methyl cation (CH+

3)). However, in this case, the VSEPR prediction is not quite true, as CH3 is actually planar, although its distortion to a pyramidal geometry requires very little energy.[41]

See also

[edit]- Bent's rule (effect of ligand electronegativity)

- Comparison of software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Linear combination of atomic orbitals

- Molecular geometry

- Molecular modelling

- Molecular Orbital Theory (MOT)

- Thomson problem

- Valence Bond Theory (VBT)

- Valency interaction formula

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Petrucci, R. H.; W. S., Harwood; F. G., Herring (2002). General Chemistry: Principles and Modern Applications (8th ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-014329-7.

- ^ Stoker, H. Stephen (2009). General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry. Cengage Learning. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-547-15281-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jolly, W. L. (1984). Modern Inorganic Chemistry. McGraw-Hill. pp. 77–90. ISBN 978-0-07-032760-3.

- ^ a b c Gillespie, R. J. (2008). "Fifty years of the VSEPR model". Coord. Chem. Rev. 252 (12–14): 1315–1327. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.007.

- ^ Bader, Richard F. W.; Gillespie, Ronald J.; MacDougall, Preston J. (1988). "A physical basis for the VSEPR model of molecular geometry". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110 (22): 7329–7336. Bibcode:1988JAChS.110.7329B. doi:10.1021/ja00230a009.

- ^ Tsuchida, Ryutarō (1939). "A New Simple Theory of Valency" 新簡易原子價論 [New simple valency theory]. Nippon Kagaku Kaishi (in Japanese). 60 (3): 245–256. doi:10.1246/nikkashi1921.60.245.

- ^ Sidgwick, N. V.; Powell, H. M. (1940). "Bakerian Lecture. Stereochemical Types and Valency Groups". Proc. R. Soc. A. 176 (965): 153–180. Bibcode:1940RSPSA.176..153S. doi:10.1098/rspa.1940.0084.

- ^ a b Gillespie, R. J.; Nyholm, R. S. (1957). "Inorganic stereochemistry". Q. Rev. Chem. Soc. 11 (4): 339. doi:10.1039/QR9571100339.

- ^ Gillespie, R. J. (1970). "The electron-pair repulsion model for molecular geometry". J. Chem. Educ. 47 (1): 18. Bibcode:1970JChEd..47...18G. doi:10.1021/ed047p18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Miessler, G. L.; Tarr, D. A. (1999). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. pp. 54–62. ISBN 978-0-13-841891-5.

- ^ Miessler, G. L.; Tarr, D. A. (1999). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-13-841891-5.

- ^ Petrucci, R. H.; W. S., Harwood; F. G., Herring (2002). General Chemistry: Principles and Modern Applications (8th ed.). Prentice-Hall. pp. 413–414 (Table 11.1). ISBN 978-0-13-014329-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2005). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0-130-39913-7.

- ^ a b Baran, E. (2000). "Mean amplitudes of vibration of the pentagonal pyramidal XeOF−

5 and IOF2−

5 anions". J. Fluorine Chem. 101: 61–63. doi:10.1016/S0022-1139(99)00194-3. - ^ Anderson, O. P. (1983). "Book reviews: Inorganic Stereochemistry (by David L. Kepert)" (PDF). Acta Crystallographica B. 39: 527–528. doi:10.1107/S0108768183002864. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

based on a systematic quantitative application of the common ideas regarding electron-pair repulsion

- ^ Brittin, W. E. (1945). "Valence Angle of the Tetrahedral Carbon Atom". J. Chem. Educ. 22 (3): 145. Bibcode:1945JChEd..22..145B. doi:10.1021/ed022p145.

- ^ "Angle Between 2 Legs of a Tetrahedron" Archived 2018-10-03 at the Wayback Machine – Maze5.net

- ^ a b c d Wiberg, E.; Holleman, A. F. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ Wulfsberg, Gary (2000). Inorganic Chemistry. University Science Books. p. 107. ISBN 9781891389016.

- ^ Power, Philip P. (September 2003). "Silicon, germanium, tin and lead analogues of acetylenes". Chem. Commun. (17): 2091–2101. doi:10.1039/B212224C. PMID 13678155.

- ^ Nagase, Shigeru; Kobayashi, Kaoru; Takagi, Nozomi (6 October 2000). "Triple bonds between heavier Group 14 elements. A theoretical approach". J. Organomet. Chem. 11 (1–2): 264–271. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)00489-7.

- ^ Sekiguchi, Akira; Kinjō, Rei; Ichinohe, Masaaki (September 2004). "A Stable Compound Containing a Silicon–Silicon Triple Bond" (PDF). Science. 305 (5691): 1755–1757. Bibcode:2004Sci...305.1755S. doi:10.1126/science.1102209. PMID 15375262. S2CID 24416825.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bellert, D.; Breckenridge, W. H. (2001). "A spectroscopic determination of the bond length of the LiOLi molecule: Strong ionic bonding". J. Chem. Phys. 114 (7): 2871. Bibcode:2001JChPh.114.2871B. doi:10.1063/1.1349424.

- ^ a b c d e Gillespie, R. J.; Robinson, E. A. (2005). "Models of molecular geometry". Chem. Soc. Rev. 34 (5): 396–407. doi:10.1039/b405359c. PMID 15852152.

- ^ Burford, Neil; Phillips, Andrew; Schurko, Robert; Wasylishen, Roderick; Richardson, John (1997). "Isolation and comprehensive solid state characterization of Cl3Al–O–PCl3". Chemical Communications. 1997 (24): 2363–2364. doi:10.1039/A705781D. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ Wells, A. F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.). Oxford Science Publications. ISBN 978-0-19-855370-0.

- ^ Peterson, W.; Holloway, H.; Coyle, A.; Williams, M. (Sep 1971). "Antiprismatic Coordination about Xenon: the Structure of Nitrosonium Octafluoroxenate(VI)". Science. 173 (4003): 1238–1239. Bibcode:1971Sci...173.1238P. doi:10.1126/science.173.4003.1238. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17775218. S2CID 22384146.

- ^ Hanson, Robert M. (1995). Molecular origami: precision scale models from paper. University Science Books. ISBN 978-0-935702-30-9.

- ^ a b Kaupp, Martin (2001). ""Non-VSEPR" Structures and Bonding in d0 Systems" (PDF). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 40 (1): 3534–3565. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20011001)40:19<3534::AID-ANIE3534>3.0.CO;2-#. PMID 11592184.

- ^ Gillespie, Ronald J.; Noury, Stéphane; Pilmé, Julien; Silvi, Bernard (2004). "An Electron Localization Function Study of the Geometry of d0 Molecules of the Period 4 Metals Ca to Mn". Inorg. Chem. 43 (10): 3248–3256. doi:10.1021/ic0354015. PMID 15132634.

- ^ Landis, C. R.; Cleveland, T.; Firman, T. K. (1995). "Making sense of the shapes of simple metal hydrides". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117 (6): 1859–1860. Bibcode:1995JAChS.117.1859L. doi:10.1021/ja00111a036.

- ^ Landis, C. R.; Cleveland, T.; Firman, T. K. (1996). "Structure of W(CH3)6". Science. 272 (5259): 179–183. doi:10.1126/science.272.5259.179f.

- ^ Zhai, H. J.; Li, S.; Dixon, D. A.; Wang, L. S. (2008). "Probing the Electronic and Structural Properties of Chromium Oxide Clusters (CrO

3)−

n and (CrO3)n (n = 1–5): Photoelectron Spectroscopy and Density Functional Calculations". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (15): 5167–77. doi:10.1021/ja077984d. PMID 18327905. - ^ King, R. Bruce (2000). "Atomic orbitals, symmetry, and coordination polyhedra". Coord. Chem. Rev. 197: 141–168. doi:10.1016/s0010-8545(99)00226-x.

- ^ Haalan, A.; Hammel, A.; Rydpal, K.; Volden, H. V. (1990). "The coordination geometry of gaseous hexamethyltungsten is not octahedral". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 (11): 4547–4549. Bibcode:1990JAChS.112.4547H. doi:10.1021/ja00167a065.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Seijo, Luis; Barandiarán, Zoila; Huzinaga, Sigeru (1991). "Ab initio model potential study of the equilibrium geometry of alkaline earth dihalides: MX2 (M=Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba; X=F, Cl, Br, I)" (PDF). J. Chem. Phys. 94 (5): 3762. Bibcode:1991JChPh..94.3762S. doi:10.1063/1.459748. hdl:10486/7315.

- ^ Seth, Michael; Schwerdtfeger, Peter; Fægri, Knut (1999). "The chemistry of superheavy elements. III. Theoretical studies on element 113 compounds". Journal of Chemical Physics. 111 (14): 6422–6433. Bibcode:1999JChPh.111.6422S. doi:10.1063/1.480168. hdl:2292/5178. S2CID 41854842.

- ^ Bae, Ch.; Han, Y.-K.; Lee, Yo. S. (18 January 2003). "Spin−Orbit and Relativistic Effects on Structures and Stabilities of Group 17 Fluorides EF3 (E = I, At, and Element 117): Relativity Induced Stability for the D3h Structure of (117)F3". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 107 (6): 852–858. Bibcode:2003JPCA..107..852B. doi:10.1021/jp026531m.

- ^ Han, Young-Kyu; Lee, Yoon Sup (1999). "Structures of RgFn (Rg = Xe, Rn, and Element 118. n = 2, 4.) Calculated by Two-component Spin-Orbit Methods. A Spin-Orbit Induced Isomer of (118)F4". Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 103 (8): 1104–1108. Bibcode:1999JPCA..103.1104H. doi:10.1021/jp983665k.

- ^ Anslyn, E. V.; Dougherty, D. A. (2006). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books. p. 57. ISBN 978-1891389313.

Further reading

[edit]- Lagowski, J. J., ed. (2004). Chemistry: Foundations and Applications. Vol. 3. New York: Macmillan. pp. 99–104. ISBN 978-0-02-865721-9.

External links

[edit]- VSEPR AR[dead link]—3D VSEPR Theory Visualization with Augmented Reality app

- 3D Chem—Chemistry, structures, and 3D molecules

- Indiana University Molecular Structure Center (IUMSC)

VSEPR theory

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Scope

The Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory is a qualitative model in chemistry that predicts the three-dimensional geometry of molecules by considering the arrangement of electron pairs around a central atom. It builds upon Lewis electron dot structures to determine how atoms are spatially oriented in a molecule, focusing on the valence shell of the central atom.[7] The core assumption of VSEPR theory is that the electron pairs—both bonding pairs and lone pairs—in the valence shell of the central atom repel one another due to electrostatic forces, leading to spatial arrangements that minimize these repulsions. This repulsion drives the electron pairs to adopt positions as far apart as possible, thereby defining the overall molecular shape. VSEPR theory primarily applies to compounds involving main-group elements and simple molecular species, where it provides reliable predictions without the need for computational intensity. Its scope extends to coordination compounds, where models like the Kepert extension adapt VSEPR principles to predict geometries around transition metal centers based on ligand electron pair repulsions. Developed in the mid-20th century, VSEPR emerged as an accessible, non-mathematical alternative to quantum mechanical calculations for rationalizing molecular structures.Historical Development

The foundational ideas of what would become VSEPR theory emerged from the work of British chemists Nevil V. Sidgwick and Herbert M. Powell, who in 1940 proposed that the repulsion between electron pairs in the valence shell of a central atom determines the overall shape of simple molecules.[8] In their Bakerian Lecture, they correlated the number of valence electron pairs (ranging from two to six) with geometric arrangements such as linear, trigonal planar, and octahedral structures, providing an early qualitative framework for predicting molecular geometries based on electron pair minimization.[8] This approach built on prior valence concepts but emphasized stereochemical implications without invoking hybridization or detailed orbital interactions.[5] The theory was formalized and refined in 1957 by Ronald J. Gillespie and Ronald S. Nyholm at University College London, who introduced the valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) model as a systematic predictive tool for inorganic stereochemistry.[7] In their seminal paper "Inorganic Stereochemistry," published in the Quarterly Reviews of the Chemical Society, they expanded on Sidgwick and Powell's ideas by incorporating the differential repulsions between bonding and lone electron pairs, enabling more accurate predictions for a wider range of main-group compounds.[7] This work established VSEPR as a cornerstone of structural inorganic chemistry, emphasizing its simplicity and utility over quantum mechanical calculations at the time.[5] By the 1960s, VSEPR had gained widespread acceptance in chemical education and research, appearing in major inorganic chemistry textbooks that disseminated the model to students and practitioners.[9] For instance, it was integrated into discussions of molecular structure in texts like F. Albert Cotton and Geoffrey Wilkinson's Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (first edition, 1962), reflecting its rapid adoption as a standard teaching tool. In the 1970s, David L. Kepert extended the model to coordination compounds of transition metals, developing the Kepert model to account for ligand repulsions while treating d-electrons as stereochemically inactive, as detailed in his 1972 book The Early Transition Metals.[10] Over subsequent decades, VSEPR's evolution included growing recognition of its limitations, particularly in explaining hypervalent molecules like SF6 or PCl5, where the model predicts expanded octets but struggles with the absence of d-orbital involvement confirmed by modern quantum calculations.[11] Critiques from the 1980s onward highlighted these issues, prompting integrations with molecular orbital (MO) theory to provide a more complete picture of bonding and geometry, such as in hybrid models that combine VSEPR heuristics with MO-derived electron densities.[9] This synthesis has refined VSEPR's role as an introductory predictive method while addressing its empirical shortcomings through computational validation.[11]Core Concepts

Valence Shell Electron Pairs

In VSEPR theory, the valence shell refers to the outermost electron shell of the central atom in a molecule, encompassing the electrons involved in bonding and those remaining as non-bonding pairs. This shell includes bonding electron pairs, which are shared between the central atom and surrounding ligand atoms, and lone pairs, which are localized entirely on the central atom without participation in bonding. These electron pairs collectively dictate the spatial arrangement of atoms by minimizing mutual repulsions within the valence shell.[7] A prerequisite for applying VSEPR theory is the construction of a Lewis structure to identify the bonding and lone pairs around the central atom. The total valence electrons for the molecule are calculated by summing the valence electrons contributed by each atom, based on their positions in the periodic table (e.g., group number for main-group elements). For the central atom, the effective valence electrons include its own contribution plus one electron per monovalent ligand atom (or adjusted for polyatomic ligands and molecular charge), which are then used to form bonds and place lone pairs. The total number of valence electron pairs around the central atom is determined by dividing these total valence electrons by 2, as each pair consists of two electrons. For example, in water (H₂O), oxygen contributes 6 valence electrons, each hydrogen contributes 1, yielding 8 total valence electrons and 4 pairs around oxygen (2 bonding, 2 lone).[12][7] The foundational principle of VSEPR relies on the repulsion among these valence shell electron pairs, which adopt geometries that minimize electrostatic interactions. Lone pairs exert stronger repulsions than bonding pairs because their electron density is more concentrated near the central atom, occupying greater effective volume and causing distortions in bond angles. In contrast, bonding pairs have their electron density delocalized between the central atom and ligands, resulting in less intense repulsions. Multiple bonds, such as double or triple bonds, are treated as a single effective bonding pair in this model, since the sigma bond dominates the spatial repulsion while pi bonds lie in the nodal plane and contribute minimally to the overall geometry. This approach simplifies predictions while capturing the essential steric effects in main-group compounds.[13][7] The sum of bonding and lone pairs, known as the steric number, provides the basis for arranging these pairs in space, though the detailed hierarchy of repulsions is considered separately.[7]Steric Number and Repulsion Strengths

In VSEPR theory, the steric number (SN) of a central atom is defined as the sum of the number of atoms directly bonded to it and the number of lone pairs residing on it, which corresponds to the total count of electron domains surrounding the atom (SN = A + E, where A represents bonded atoms and E represents lone pairs in the AXE classification system). This quantification provides a foundational metric for predicting molecular geometry by assessing the spatial arrangement needed to minimize electron pair repulsions. The concept builds directly on the principles outlined by Gillespie and Nyholm, who emphasized the role of valence electron pairs in dictating stereochemistry.[7][14] Electron domains, or regions of high electron density around the central atom, encompass both bonding pairs and lone pairs; notably, multiple bonds—such as double or triple bonds—are treated as a single domain equivalent to a single bond for repulsion purposes, as the electron density is concentrated in a similar directional lobe. This treatment simplifies the model while capturing the effective spatial occupancy, ensuring that the geometry reflects the overall repulsion dynamics rather than bond multiplicity alone. Gillespie and Nyholm's framework underscores that these domains arrange to achieve the lowest possible energy configuration through mutual repulsion.[7][15] The relative strengths of repulsions between electron domains follow a clear hierarchy: lone pair–lone pair (lp–lp) interactions are the strongest, exerting the greatest force due to the unshared electrons' larger effective volume; lone pair–bonding pair (lp–bp) repulsions are intermediate; and bonding pair–bonding pair (bp–bp) interactions are the weakest, as shared electrons are partially constrained by nuclear attraction from adjacent atoms. This ordering, central to VSEPR predictions, can be visualized through qualitative energy diagrams where lp–lp repulsions elevate the potential energy most significantly, followed by lp–bp, with bp–bp contributing the least distortion. The hierarchy originates from the differential spatial demands of lone versus bonding pairs, as articulated in the foundational VSEPR model.[7][16] The ideal geometries derived from the steric number minimize these repulsions by positioning domains as far apart as possible on the valence shell surface. For SN = 2, the arrangement is linear; for SN = 3, trigonal planar; for SN = 4, tetrahedral; for SN = 5, trigonal bipyramidal; and for SN = 6, octahedral. These configurations represent the baseline electron pair geometries before accounting for lone pair distortions, providing a systematic basis for VSEPR applications across main-group compounds.[7]| Steric Number (SN) | Ideal Electron Pair Geometry |

|---|---|

| 2 | Linear |

| 3 | Trigonal planar |

| 4 | Tetrahedral |

| 5 | Trigonal bipyramidal |

| 6 | Octahedral |

AXE Notation and Geometry Prediction

Notation for Main-Group Elements

The AXE notation provides a systematic way to classify molecules and predict their geometries under the VSEPR theory for compounds of main-group elements, particularly those in the p-block. In this scheme, "A" denotes the central atom, "X" represents each surrounding atom directly bonded to the central atom (often called ligands), and "E" stands for each lone pair of electrons residing on the central atom. This notation simplifies the analysis by focusing on the total number of electron domains around the central atom, treating both bonding pairs and lone pairs as repelling entities.[7] To apply AXE notation, the process begins with constructing the Lewis structure of the molecule, which reveals the central atom, the bonds to surrounding atoms (counted as X), and any non-bonding electron pairs on the central atom (counted as E). The steric number (SN) is then determined as the sum SN = X + E, corresponding to the total electron pairs in the valence shell; this dictates the electron pair geometry, such as linear for SN=2, trigonal planar for SN=3, or octahedral for SN=6. The molecular geometry follows by positioning the X groups around this electron arrangement, with E pairs ideally placed to maximize separation and minimize repulsion, often in less sterically demanding locations. For instance, in cases of higher SN like 5 or 6, lone pairs may preferentially occupy equatorial positions in trigonal bipyramidal or axial/equatorial distinctions in octahedral arrangements due to varying repulsion strengths.[7][17] Common classifications illustrate the notation's utility. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is AX₂, featuring a central carbon bonded to two oxygens with no lone pairs, yielding a linear molecular geometry with a 180° bond angle. Ammonia (NH₃) is AX₃E, with nitrogen bonded to three hydrogens and one lone pair, resulting in a trigonal pyramidal shape derived from a tetrahedral electron geometry, with H-N-H angles of approximately 107°. Xenon tetrafluoride (XeF₄) exemplifies AX₄E₂, where xenon bonds to four fluorines and has two lone pairs, leading to a square planar molecular geometry from an octahedral electron arrangement, with F-Xe-F angles of 90°. These examples highlight how AXE notation guides predictions for p-block central atoms.[7][7][17] The AXE notation assumes octet adherence or expanded octets without significant d-orbital participation, making it primarily valid for main-group elements in the p-block where valence electrons occupy s and p orbitals. It does not account for cases involving transition metals or substantial d-orbital involvement, which are addressed separately.[7][17]Extension to Transition Metals

The Kepert model, introduced by D. L. Kepert in 1972, adapts VSEPR theory specifically for predicting the coordination geometries of transition metal complexes by considering ligands as the dominant electron domains that generate repulsions.[18] In this framework, the geometry is determined primarily by the coordination number (CN), which equates to the number of ligand attachments (denoted as X in an AXE-type notation, where E=0 due to the negligible stereochemical role of lone pairs on the central metal). This approach treats the metal center as a point from which ligands repel each other to minimize energy, much like electron pairs in standard VSEPR, but it emphasizes the positional arrangement on a spherical surface around the metal.[18] Key differences from VSEPR applications to main-group elements arise because transition metal complexes typically ignore metal-centered lone pairs, concentrating instead on inter-ligand repulsions, which enables higher coordination numbers such as 7–9 that are stabilized by d-orbital participation. The model accommodates variable bond types (ionic or covalent) between metal and ligands, and repulsion strengths follow a similar hierarchy to VSEPR—close approaches between ligands are disfavored—but geometries often exhibit angular distortions influenced by crystal field stabilization energies.[19] Notation is adapted for simplicity, using ML to indicate the metal (M) and number of ligands (n = CN), for instance, ML for square planar arrangements common in d configurations like Ni(II) complexes. Illustrative examples highlight the model's predictive power: for CN=6, the octahedral geometry (ML) is standard, as in hexaamminecobalt(III) ion, [Co(NH)], where six equivalent ligands occupy positions to maximize separation at 90° and 180° angles. For certain electronic configurations, such as d or d, the model predicts trigonal prismatic ML structures over octahedral, exemplified by the layered sulfide MoS (where Mo is effectively six-coordinate to S) or the alkyl complex [Ta(CH)], due to reduced repulsion in the prismatic arrangement for these cases. The steric number here aligns directly with the coordination number, serving as the basis for these predictions.Molecular Geometries

Basic Shapes and Bond Angles

The Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory determines the arrangement of electron pairs around a central atom, leading to specific electron geometries based on the steric number (SN), defined as the total number of bonding pairs and lone pairs in the valence shell. These geometries minimize repulsions between electron pairs, resulting in characteristic ideal bond angles. The basic electron geometries for SN = 2 to 6 are as follows:| Steric Number (SN) | Electron Geometry | Ideal Bond Angles |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Linear | 180° |

| 3 | Trigonal planar | 120° |

| 4 | Tetrahedral | 109.5° |

| 5 | Trigonal bipyramidal | 90° (axial-equatorial), 120° (equatorial-equatorial), 180° (axial-axial) |

| 6 | Octahedral | 90° (adjacent), 180° (opposite) |

| SN | AXE Notation | Molecular Geometry | Description of 3D Arrangement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | AX2 | Linear | Two atoms aligned opposite the central atom along a straight line. |

| 3 | AX3 | Trigonal planar | Three atoms in a plane, equally spaced around the central atom. |

| AX2E | Bent | Two atoms with a lone pair, forming a V-shape in the plane of the trigonal arrangement. | |

| 4 | AX4 | Tetrahedral | Four atoms at the vertices of a tetrahedron, all equivalent. |

| AX3E | Trigonal pyramidal | Three atoms forming a pyramid with the central atom at the apex. | |

| AX2E2 | Bent | Two atoms with two lone pairs, resulting in an angular structure. | |

| 5 | AX5 | Trigonal bipyramidal | Three equatorial atoms in a plane (120° apart) and two axial atoms perpendicular (90° to equatorial). |

| AX4E | Seesaw | Four atoms: two axial, two equatorial, resembling a seesaw with the central atom as fulcrum. | |

| AX3E2 | T-shaped | Three atoms: two axial and one equatorial, forming a T configuration. | |

| AX2E3 | Linear | Two atoms in axial positions, with three equatorial lone pairs. | |

| 6 | AX6 | Octahedral | Six atoms at the vertices of an octahedron, all equivalent positions. |

| AX5E | Square pyramidal | Five atoms: four basal in a square plane, one apical perpendicular. | |

| AX4E2 | Square planar | Four atoms in a square plane, with lone pairs trans to each other. |