Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nitrate

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

Nitrate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| NO− 3 | |

| Molar mass | 62.004 g·mol−1 |

| Conjugate acid | Nitric acid |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

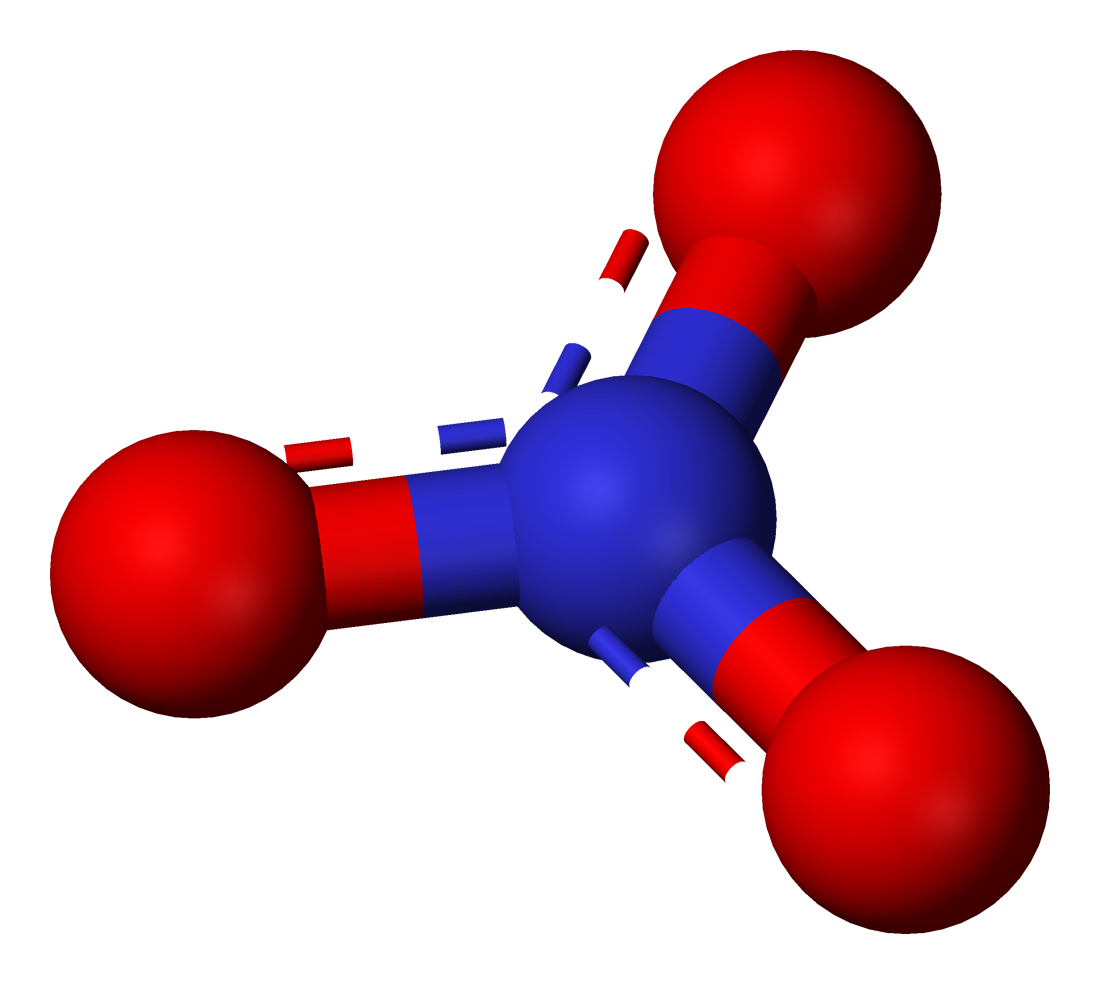

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula NO−

3. Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives.[1] Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insoluble nitrate is bismuth oxynitrate.

Chemical structure

[edit]

The nitrate anion is the conjugate base of nitric acid, consisting of one central nitrogen atom surrounded by three identically bonded oxygen atoms in a trigonal planar arrangement. The nitrate ion carries a formal charge of −1.[citation needed] This charge results from a combination formal charge in which each of the three oxygens carries a −2⁄3 charge,[citation needed] whereas the nitrogen carries a +1 charge, all these adding up to formal charge of the polyatomic nitrate ion.[citation needed] This arrangement is commonly used as an example of resonance. Like the isoelectronic carbonate ion, the nitrate ion can be represented by three resonance structures:

Chemical and biochemical properties

[edit]In the NO−

3 anion, the oxidation state of the central nitrogen atom is V (+5). This corresponds to the highest possible oxidation number of nitrogen. Nitrate is a potentially powerful oxidizer as evidenced by its explosive behaviour at high temperature when it is detonated in ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), or black powder, ignited by the shock wave of a primary explosive. In contrast to red fuming nitric acid (HNO3/N2O4), or concentrated nitric acid (HNO3), nitrate in aqueous solution at neutral or high pH is only a weak oxidizing agent in redox reactions in which the reductant does not produce hydrogen ions (such as mercury going to calomel). However, it is still a strong oxidizer when the reductant does produce hydrogen ions, such as in the oxidation of hydrogen itself. Nitrate is stable in the absence of microorganisms, or reductants such as organic matter. In fact, nitrogen gas is thermodynamically stable in the presence of 1 atm of oxygen only in very acidic conditions, and otherwise would combine with it to form nitrate. This is shown by subtracting the two oxidation reactions:[2]

- N2 + 6 H2O → 2 NO−3 + 12 H+ + 10 e−

- 2 H2O → O2 + 4 H+ + 4 e−

giving:

- 2 N2 + 5 O2 + 2 H2O → 4 NO−3 + 4 H+

Dividing by 0.0118 and rearranging gives the equilibrium relation:

However, in reality, nitrogen, oxygen, and water do not combine directly to form nitrate. Rather, a reductant such as hydrogen reacts with nitrogen to produce "fixed nitrogen" such as ammonia, which is then oxidized, eventually becoming nitrate. Nitrate does not accumulate to high levels in nature because it reacts with reductants in the process called denitrification (see Nitrogen cycle).

Nitrate is used as a powerful terminal electron acceptor by denitrifying bacteria to deliver the energy they need to thrive. Under anaerobic conditions, nitrate is the strongest electron acceptor used by prokaryote microorganisms (bacteria and archaea) to respirate. The redox couple NO−3/N2 is at the top of the redox scale for the anaerobic respiration, just below the couple oxygen (O2/H2O), but above the couples Mn(IV)/Mn(II), Fe(III)/Fe(II), SO2−4/HS−, CO2/CH4. In natural waters inevitably contaminated by microorganisms, nitrate is a quite unstable and labile dissolved chemical species because it is metabolised by denitrifying bacteria. Water samples for nitrate/nitrite analyses need to be kept at 4 °C in a refrigerated room and analysed as quick as possible to limit the loss of nitrate.

In the first step of the denitrification process, dissolved nitrate (NO−3) is catalytically reduced into nitrite (NO−2) by the enzymatic activity of bacteria. In aqueous solution, dissolved nitrite, N(III), is a more powerful oxidizer that nitrate, N(V), because it has to accept less electrons and its reduction is less kinetically hindered than that of nitrate.

During the biological denitrification process, further nitrite reduction also gives rise to another powerful oxidizing agent: nitric oxide (NO). NO can fix on myoglobin, accentuating its red coloration. NO is an important biological signaling molecule and intervenes in the vasodilation process. Still, it can also produce free radicals in biological tissues, accelerating their degradation and aging process. The reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by NO contribute to the oxidative stress, a condition involved in vascular dysfunction and atherogenesis.[3]

Detection in chemical analysis

[edit]The nitrate anion is commonly analysed in water by ion chromatography (IC) along with other anions also present in the solution. The main advantage of IC is its ease and the simultaneous analysis of all the anions present in the aqueous sample. Since the emergence of IC instruments in the 1980s, this separation technique, coupled with many detectors, has become commonplace in the chemical analysis laboratory and is the preferred and most widely used method for nitrate and nitrite analyses.[4]

Previously, nitrate determination relied on spectrophotometric and colorimetric measurements after a specific reagent is added to the solution to reveal a characteristic color (often red because it absorbs visible light in the blue). Because of interferences with the brown color of dissolved organic matter (DOM: humic and fulvic acids) often present in soil pore water, artefacts can easily affect the absorbance values. In case of weak interference, a blank measurement with only a naturally brown-colored water sample can be sufficient to subtract the undesired background from the measured sample absorbance. If the DOM brown color is too intense, the water samples must be pretreated, and inorganic nitrogen species must be separated before measurement. Meanwhile, for clear water samples, colorimetric instruments retain the advantage of being less expensive and sometimes portable, making them an affordable option for fast routine controls or field measurements.

Colorimetric methods for the specific detection of nitrate (NO−3) often rely on its conversion to nitrite (NO−2) followed by nitrite-specific tests. The reduction of nitrate to nitrite can be effected by a copper-cadmium alloy, metallic zinc,[5] or hydrazine. The most popular of these assays is the Griess test, whereby nitrite is converted to a deeply red colored azo dye suited for UV–vis spectrophotometry analysis. The method exploits the reactivity of nitrous acid (HNO2) derived from the acidification of nitrite. Nitrous acid selectively reacts with aromatic amines to give diazonium salts, which in turn couple with a second reagent to give the azo dye. The detection limit is 0.02 to 2 μM.[6] Such methods have been highly adapted to biological samples[7] and soil samples.[8][9]

In the dimethylphenol method, 1 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) is added to 200 μL of the solution being tested for nitrate. Under strongly acidic conditions, nitrate ions react with 2,6-dimethylphenol, forming a yellow compound, 4-nitro-2,6-dimethylphenol. This occurs through electrophilic aromatic substitution where the intermediate nitronium (+NO2) ions attack the aromatic ring of dimethylphenol. The resulting product (ortho- or para-nitro-dimethylphenol) is analyzed using UV-vis spectrophotometry at 345 nm according to the Lambert-Beer law.[10][11]

Another colorimetric method based on the chromotropic acid (dihydroxynaphthalene-disulfonic acid) was also developed by West and Lyles in 1960 for the direct spectrophotometric determination of nitrate anions.[12]

If formic acid is added to a mixture of brucine (an alkaloid related to strychnine) and potassium nitrate (KNO3), its color instantly turns red. This reaction has been used for the direct colorimetric detection of nitrates.[13]

For direct online chemical analysis using a flow-through system, the water sample is introduced by a peristaltic pump in a flow injection analyzer, and the nitrate or resulting nitrite-containing effluent is then combined with a reagent for its colorimetric detection.

Occurrence and production

[edit]Nitrate salts are found naturally on earth in arid environments as large deposits, particularly of nitratine, a major source of sodium nitrate.

Nitrates are produced by a number of species of nitrifying bacteria in the natural environment using ammonia or urea as a source of nitrogen and source of free energy. Nitrate compounds for gunpowder were historically produced, in the absence of mineral nitrate sources, by means of various fermentation processes using urine and dung.

Lightning strikes in earth's nitrogen- and oxygen-rich atmosphere produce a mixture of oxides of nitrogen, which form nitrous ions and nitrate ions, which are washed from the atmosphere by rain or in occult deposition.

Nitrates are produced industrially from nitric acid.[1]

Uses

[edit]Agriculture

[edit]Nitrate is a chemical compound that serves as a primary form of nitrogen for many plants. This essential nutrient is used by plants to synthesize proteins, nucleic acids, and other vital organic molecules.[14] The transformation of atmospheric nitrogen into nitrate is facilitated by certain bacteria and lightning in the nitrogen cycle, which exemplifies nature's ability to convert a relatively inert molecule into a form that is crucial for biological productivity.[15]

Nitrates are used as fertilizers in agriculture because of their high solubility and biodegradability. The main nitrate fertilizers are ammonium, sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium salts. Several billion kilograms are produced annually for this purpose.[1] The significance of nitrate extends beyond its role as a nutrient since it acts as a signaling molecule in plants, regulating processes such as root growth, flowering, and leaf development.[16]

While nitrate is beneficial for agriculture since it enhances soil fertility and crop yields, its excessive use can lead to nutrient runoff, water pollution, and the proliferation of aquatic dead zones.[17] Therefore, sustainable agricultural practices that balance productivity with environmental stewardship are necessary. Nitrate's importance in ecosystems is evident since it supports the growth and development of plants, contributing to biodiversity and ecological balance.[18]

Firearms

[edit]Nitrates are used as oxidizing agents, most notably in explosives, where the rapid oxidation of carbon compounds liberates large volumes of gases (see gunpowder as an example).

Industrial

[edit]Sodium nitrate is used to remove air bubbles from molten glass and some ceramics. Mixtures of molten salts are used to harden the surface of some metals.[1]

Photographic film

[edit]Nitrate was also used as a film stock through nitrocellulose. Due to its high combustibility, the film making studios swapped to cellulose acetate safety film in 1950.

Medicinal and pharmaceutical use

[edit]In the medical field, nitrate-derived organic esters, such as glyceryl trinitrate, isosorbide dinitrate, and isosorbide mononitrate, are used in the prophylaxis and management of acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, acute pulmonary oedema.[19] This class of drug, to which amyl nitrite also belongs, is known as nitrovasodilators.

Toxicity and safety

[edit]The two areas of concerns about the toxicity of nitrate are the following:

- nitrate reduced by the microbial activity of nitrate reducing bacteria is the precursor of nitrite in water and in the lower gastrointestinal tract. Nitrite is a precursor to carcinogenic nitrosamines, and;

- via the formation of nitrite, nitrate is implicated in methemoglobinemia, a disorder of hemoglobin in red blood cells susceptible to especially affect infants and toddlers.[20][21]

Methemoglobinemia

[edit]One of the most common cause of methemoglobinemia in infants is due to the ingestion of nitrates and nitrites through well water or foods.

In fact, nitrates (NO−3), often present at too high concentration in drinkwater, are only the precursor chemical species of nitrites (NO−2), the real culprits of methemoglobinemia. Nitrites produced by the microbial reduction of nitrate (directly in the drinkwater, or after ingestion by the infant's digestive system) are more powerful oxidizers than nitrates and are the chemical agent really responsible for the oxidation of Fe2+ into Fe3+ in the tetrapyrrole heme of hemoglobin. Indeed, nitrate anions are too weak oxidizers in aqueous solution to be able to directly, or at least sufficiently rapidly, oxidize Fe2+ into Fe3+, because of kinetics limitations.

Infants younger than 4 months are at greater risk given that they drink more water per body weight, they have a lower NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase activity, and they have a higher level of fetal hemoglobin which converts more easily to methemoglobin. Additionally, infants are at an increased risk after an episode of gastroenteritis due to the production of nitrites by bacteria.[22]

However, other causes than nitrates can also affect infants and pregnant women.[23][24] Indeed, the blue baby syndrome can also be caused by a number of other factors such as the cyanotic heart disease, a congenital heart defect resulting in low levels of oxygen in the blood,[25] or by gastric upset, such as diarrheal infection, protein intolerance, heavy metal toxicity, etc.[26]

Drinking water standards

[edit]Through the Safe Drinking Water Act, the United States Environmental Protection Agency has set a maximum contaminant level of 10 mg/L or 10 ppm of nitrate in drinking water.[27]

An acceptable daily intake (ADI) for nitrate ions was established in the range of 0–3.7 mg (kg body weight)−1 day−1 by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JEFCA).[28]

Aquatic toxicity

[edit]

In freshwater or estuarine systems close to land, nitrate can reach concentrations that are lethal to fish. While nitrate is much less toxic than ammonia,[29] levels over 30 ppm of nitrate can inhibit growth, impair the immune system and cause stress in some aquatic species.[30] Nitrate toxicity remains a subject of debate.[31]

In most cases of excess nitrate concentrations in aquatic systems, the primary sources are wastewater discharges, as well as surface runoff from agricultural or landscaped areas that have received excess nitrate fertilizer. The resulting eutrophication and algae blooms result in anoxia and dead zones. As a consequence, as nitrate forms a component of total dissolved solids, they are widely used as an indicator of water quality.

Human impacts on ecosystems through nitrate deposition

[edit]

Nitrate deposition into ecosystems has markedly increased due to anthropogenic activities, notably from the widespread application of nitrogen-rich fertilizers in agriculture and the emissions from fossil fuel combustion.[32] Annually, about 195 million metric tons of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers are used worldwide, with nitrates constituting a significant portion of this amount.[33] In regions with intensive agriculture, such as parts of the U.S., China, and India, the use of nitrogen fertilizers can exceed 200 kilograms per hectare.[33]

The impact of increased nitrate deposition extends beyond plant communities to affect soil microbial populations.[34] The change in soil chemistry and nutrient dynamics can disrupt the natural processes of nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification, leading to altered microbial community structures and functions. This disruption can further impact the nutrient cycling and overall ecosystem health.[35]

Dietary nitrate

[edit]A source of nitrate in the human diets arises from the consumption of leafy green foods, such as spinach and arugula. NO−

3 can be present in beetroot juice. Drinking water represents also a primary nitrate intake source.[36]

Nitrate ingestion rapidly increases the plasma nitrate concentration by a factor of 2 to 3, and this elevated nitrate concentration can be maintained for more than 2 weeks. Increased plasma nitrate enhances the production of nitric oxide, NO. Nitric oxide is a physiological signaling molecule which intervenes in, among other things, regulation of muscle blood flow and mitochondrial respiration.[37]

Cured meats

[edit]Nitrite (NO−2) consumption is primarily determined by the amount of processed meats eaten, and the concentration of nitrates (NO−3) added to these meats (bacon, sausages…) for their curing. Although nitrites are the nitrogen species chiefly used in meat curing, nitrates are used as well and can be transformed into nitrite by microorganisms, or in the digestion process, starting by their dissolution in saliva and their contact with the microbiota of the mouth. Nitrites lead to the formation of carcinogenic nitrosamines.[38] The production of nitrosamines may be inhibited by the use of the antioxidants vitamin C and the alpha-tocopherol form of vitamin E during curing.[39]

Many meat processors claim their meats (e.g. bacon) is "uncured" – which is a marketing claim with no factual basis: there is no such thing as "uncured" bacon (as that would be, essentially, raw sliced pork belly).[40][better source needed] "Uncured" meat is in fact actually cured with nitrites with virtually no distinction in process – the only difference being the USDA labeling requirement between nitrite of vegetable origin (such as from celery) vs. "synthetic" sodium nitrite. An analogy would be purified "sea salt" vs. sodium chloride – both being exactly the same chemical with the only essential difference being the origin.

Anti-hypertensive diets, such as the DASH diet, typically contain high levels of nitrates, which are first reduced to nitrite in the saliva, as detected in saliva testing, prior to forming nitric oxide (NO).[36]

Domestic animal feed

[edit]Symptoms of nitrate poisoning in domestic animals include increased heart rate and respiration; in advanced cases blood and tissue may turn a blue or brown color. Feed can be tested for nitrate; treatment consists of supplementing or substituting existing supplies with lower nitrate material. Safe levels of nitrate for various types of livestock are as follows:[41]

| Category | %NO3 | %NO3–N | %KNO3 | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | < 0.5 | < 0.12 | < 0.81 | Generally safe for beef cattle and sheep |

| 2 | 0.5–1.0 | 0.12–0.23 | 0.81–1.63 | Caution: some subclinical symptoms may appear in pregnant horses, sheep and beef cattle |

| 3 | 1.0 | 0.23 | 1.63 | High nitrate problems: death losses and abortions can occur in beef cattle and sheep |

| 4 | < 1.23 | < 0.28 | < 2.00 | Maximum safe level for horses. Do not feed high nitrate forages to pregnant mares |

The values above are on a dry (moisture-free) basis.

Salts and covalent derivatives

[edit]Nitrate formation with elements of the periodic table:

See also

[edit]- Ammonium

- Eutrophication

- f-ratio in oceanography

- Frost diagram

- Nitrification

- Nitratine

- Nitrite, the anion NO−

2 - Nitrogen oxide

- Nitrogen trioxide, the neutral radical NO

3 - Peroxynitrate, OONO–

2 - Sodium nitrate

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Laue W, Thiemann M, Scheibler E, Wiegand KW (2006). "Nitrates and Nitrites". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_265. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Marcel Pourbaix and N. de Zoubov (1974). "Nitrogen". In Marcel Pourbaix (ed.). Atlas of Electrochemical Equilibria in Aqueous Solutions (PDF). pp. 49, 497, 500.

- ^ Lubos E, Handy DE, Loscalzo J (May 2008). "Role of oxidative stress and nitric oxide in atherothrombosis". Frontiers in Bioscience. 13 (13). IMR Press: 5323–5344. doi:10.2741/3084. PMC 2617738. PMID 18508590.

- ^ Michalski R (2006). "Ion chromatography as a reference method for determination of inorganic ions in water and wastewater". Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry. 36 (2): 107–127. doi:10.1080/10408340600713678. ISSN 1040-8347.

- ^ da Ascenção WD, Augusto CC, de Melo VH, Batista BL (2024-05-23). "A simple, ecofriendly, and fast method for nitrate quantification in bottled water using visible spectrophotometry". Toxics. 12 (6): 383. doi:10.3390/toxics12060383. ISSN 2305-6304. PMC 11209534. PMID 38922063.

- ^ Moorcroft MJ, Davis J, Compton RG (June 2001). "Detection and determination of nitrate and nitrite: a review". Talanta. 54 (5): 785–803. doi:10.1016/S0039-9140(01)00323-X. PMID 18968301.

- ^ Ellis G, Adatia I, Yazdanpanah M, Makela SK (June 1998). "Nitrite and nitrate analyses: a clinical biochemistry perspective". Clinical Biochemistry. 31 (4): 195–220. doi:10.1016/S0009-9120(98)00015-0. PMID 9646943.

- ^ Bremner JM (1965), "Inorganic forms of nitrogen", Methods of Soil Analysis, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1179–1237, doi:10.2134/agronmonogr9.2.c33, ISBN 978-0-89118-204-7, retrieved 2025-03-03

- ^ Guiot J (1975). "Estimation of soil nitrogen reserves by determination of mineral nitrogen". Revue de l'Agriculture (Bruxelles). 28 (5): 1117–1132 – via CABI Databases.

- ^ US-EPA. "Approved method for water and wastewater analysis, 40 CFR part 136; and drinking water, 40 CFR part 141.23" (PDF). Retrieved 2025-04-14.

- ^ Hach Company (2025). "TNTplus 835/836 nitrate method 10206. Spectrophotometric measurement of nitrate in water and wastewater" (PDF). Retrieved 2025-04-14..

- ^ West PW, Lyles GL (1960). "A new method for the determination of nitrates". Analytica Chimica Acta. 23: 227–232. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(60)80057-8. ISSN 0003-2670.

- ^ Baker AS (1967-05-01). "Colorimetric determination of nitrate in soil and plant extracts with brucine". ACS Publications. doi:10.1021/jf60153a004. Retrieved 2025-03-01.

- ^ Zhang GB, Meng S, Gong JM (November 2018). "The Expected and Unexpected Roles of Nitrate Transporters in Plant Abiotic Stress Resistance and Their Regulation". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 19 (11): 3535. doi:10.3390/ijms19113535. PMC 6274899. PMID 30423982.

- ^ Chuang HP (2018-11-26). "Insight on transformation pathways of nitrogen species and functional genes expression by targeted players involved in nitrogen cycle". Impact. 2018 (8): 58–59. doi:10.21820/23987073.2018.8.58. ISSN 2398-7073.

- ^ Liu B, Wu J, Yang S, Schiefelbein J, Gan Y (July 2020). Xu G (ed.). "Nitrate regulation of lateral root and root hair development in plants". Journal of Experimental Botany. 71 (15): 4405–4414. doi:10.1093/jxb/erz536. PMC 7382377. PMID 31796961.

- ^ Bashir U, Lone FA, Bhat RA, Mir SA, Dar ZA, Dar SA (2020). "Concerns and Threats of Contamination on Aquatic Ecosystems". In Hakeem KR, Bhat RA, Qadri H (eds.). Bioremediation and Biotechnology. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-35691-0_1. ISBN 978-3-030-35690-3.

- ^ Kirchmann H, Johnston AE, Bergström LF (August 2002). "Possibilities for reducing nitrate leaching from agricultural land". Ambio. 31 (5): 404–408. Bibcode:2002Ambio..31..404K. doi:10.1579/0044-7447-31.5.404. PMID 12374048.

- ^ Soman B, Vijayaraghavan G (April 2017). "The role of organic nitrates in the optimal medical management of angina". e-Journal of Cardiology Practice. 15 (2). Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- ^ Powlson DS, Addiscott TM, Benjamin N, Cassman KG, de Kok TM, van Grinsven H, et al. (2008). "When does nitrate become a risk for humans?". Journal of Environmental Quality. 37 (2): 291–295. Bibcode:2008JEnvQ..37..291P. doi:10.2134/jeq2007.0177. PMID 18268290. S2CID 14097832.

- ^ "Nitrate and Nitrite Poisoning: Introduction". The Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ^ Smith-Whitley K, Kwiatkowski JL (2000). "Chapter 489: Hemoglobinopathies". In Kliegman RM (ed.). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (21st ed.). Elsevier Inc. pp. 2540–2558. ISBN 978-0-323-52950-1.

- ^ Addiscott TM, Benjamin N (2006). "Nitrate and human health". Soil Use and Management. 20 (2): 98–104. doi:10.1111/j.1475-2743.2004.tb00344.x. S2CID 96297102.

- ^ Avery AA (July 1999). "Infantile methemoglobinemia: reexamining the role of drinking water nitrates". Environmental Health Perspectives. 107 (7): 583–6. Bibcode:1999EnvHP.107..583A. doi:10.1289/ehp.99107583. PMC 1566680. PMID 10379005.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Cyanotic heart disease

- ^ Manassaram DM, Backer LC, Messing R, Fleming LE, Luke B, Monteilh CP (October 2010). "Nitrates in drinking water and methemoglobin levels in pregnancy: a longitudinal study". Environmental Health. 9 (1): 60. Bibcode:2010EnvHe...9...60M. doi:10.1186/1476-069x-9-60. PMC 2967503. PMID 20946657.

- ^ "4. What are EPA's drinking water regulations for nitrate?". Ground Water & Drinking Water. 20 September 2016. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- ^ Bagheri H, Hajian A, Rezaei M, Shirzadmehr A (February 2017). "Composite of Cu metal nanoparticles-multiwall carbon nanotubes-reduced graphene oxide as a novel and high performance platform of the electrochemical sensor for simultaneous determination of nitrite and nitrate". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 324 (Pt B): 762–772. Bibcode:2017JHzM..324..762B. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.11.055. PMID 27894754.

- ^ Romano N, Zeng C (September 2007). "Acute toxicity of sodium nitrate, potassium nitrate, and potassium chloride and their effects on the hemolymph composition and gill structure of early juvenile blue swimmer crabs(Portunus pelagicus Linnaeus, 1758) (Decapoda, Brachyura, Portunidae)". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 26 (9): 1955–1962. Bibcode:2007EnvTC..26.1955R. doi:10.1897/07-144r.1. PMID 17705664. S2CID 19854591.

- ^ Sharpe, Shirlie. "Nitrates in the Aquarium". About.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Romano N, Zeng C (December 2007). "Effects of potassium on nitrate mediated alterations of osmoregulation in marine crabs". Aquatic Toxicology. 85 (3): 202–208. Bibcode:2007AqTox..85..202R. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.09.004. PMID 17942166.

- ^ Kanakidou M, Myriokefalitakis S, Daskalakis N, Fanourgakis G, Nenes A, Baker AR, et al. (May 2016). "Past, Present and Future Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 73 (5): 2039–2047. Bibcode:2016JAtS...73.2039K. doi:10.1175/JAS-D-15-0278.1. PMC 7398418. PMID 32747838.

- ^ a b "Global fertilizer consumption by nutrient 1965-2021". Statista. Retrieved 2024-04-20.

- ^ Li Y, Zou N, Liang X, Zhou X, Guo S, Wang Y, et al. (2023-01-10). "Effects of nitrogen input on soil bacterial community structure and soil nitrogen cycling in the rhizosphere soil of Lycium barbarum L". Frontiers in Microbiology. 13 1070817. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.1070817. PMC 9871820. PMID 36704567.

- ^ Melillo JM (April 2021). "Disruption of the global nitrogen cycle: A grand challenge for the twenty-first century: This article belongs to Ambio's 50th Anniversary Collection. Theme: Eutrophication". Ambio. 50 (4): 759–763. Bibcode:2021Ambio..50..759M. doi:10.1007/s13280-020-01429-2. PMC 7982378. PMID 33534057.

- ^ a b Hord NG, Tang Y, Bryan NS (July 2009). "Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (1): 1–10. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27131. PMID 19439460.

- ^ Maughan RJ (2013). Food, Nutrition and Sports Performance III. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-415-62792-4.

- ^ Bingham SA, Hughes R, Cross AJ (November 2002). "Effect of white versus red meat on endogenous N-nitrosation in the human colon and further evidence of a dose response". The Journal of Nutrition. 132 (11 Suppl): 3522S – 3525S. doi:10.1093/jn/132.11.3522S. PMID 12421881.

- ^ Parthasarathy DK, Bryan NS (November 2012). "Sodium nitrite: the "cure" for nitric oxide insufficiency". Meat Science. 92 (3): 274–279. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.03.001. PMID 22464105.

- ^ "Is There a Difference Between Cured and Uncured Bacon?". 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Nitrate Risk in Forage Crops - Frequently Asked Questions". Agriculture and Rural Development. Government of Alberta. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

External links

[edit]Nitrate

View on GrokipediaHistory

Discovery and Natural Exploitation

Potassium nitrate, commonly known as saltpeter, was recognized and exploited in ancient China by the 9th century AD, where Taoist alchemists combined it with charcoal and sulfur to create gunpowder, initially for medicinal and pyrotechnic purposes before military applications around AD 904. Natural deposits formed through bacterial oxidation of ammonia in nitrogen-rich environments such as animal dung heaps, cave sediments, and wall efflorescences were harvested and refined by leaching and crystallization, as documented in medieval Chinese texts on pyrotechnics. Similar practices emerged in India, with saltpeter mining from natural beds supporting regional explosive production by the 13th century, predating widespread European adoption.[10][11][12] In Europe, pre-industrial exploitation focused on domestic collection from stable floors, cesspits, and plaster walls, where urine-derived ammonia underwent nitrification; governments like England's established "saltpeter men" in the 16th century to extract and purify it for gunpowder amid scarce natural outcrops. These methods yielded impure potassium nitrate essential for black powder, sustaining artillery and small arms until the 19th century.[13] Vast sodium nitrate deposits in Chile's Atacama Desert were first systematically exploited in the early 19th century, with initial works established around 1826 near Iquique following reconnaissance of the hyper-arid caliche layers formed by evaporation of ancient marine and atmospheric nitrates. Commercial scaling by the 1840s transformed Chile into the world's primary supplier, exporting millions of tons annually for fertilizers that boosted European crop productivity via Liebig's agricultural chemistry and for ammonium nitrate explosives pivotal in mining and World War I munitions, until displaced by synthetic processes post-1910.[14][15] Scientific observations from the late 18th century onward linked lightning strikes to nitrate enrichment in soils, as electrical discharges fixed atmospheric nitrogen into soluble oxides washed into the ground by rain, providing a key natural input for plant fertility independent of microbial action; quantitative estimates later confirmed global contributions equivalent to several million tons annually.[16][17]Transition to Synthetic Production

The development of synthetic nitrate production marked a pivotal shift from dependence on finite natural deposits, such as Chilean caliche, to scalable industrial methods reliant on atmospheric nitrogen fixation. In 1909, Fritz Haber achieved laboratory-scale synthesis of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen gases using high pressure, elevated temperature, and an iron catalyst, laying the groundwork for large-scale production.[18] This process was industrially realized in 1913 when BASF commissioned the world's first ammonia synthesis plant at Oppau, Germany, producing approximately 30 tons per day initially.[19] Ammonia served as the precursor for nitric acid via the Ostwald process, in which ammonia is catalytically oxidized to nitric oxide, further oxidized to nitrogen dioxide, and absorbed in water to yield HNO3; Wilhelm Ostwald patented the core oxidation steps in 1902, with the first commercial plant operational by 1908.[20] World War I accelerated adoption amid acute shortages of imported nitrates for munitions, as Britain's naval blockade severed Germany's access to Chilean sodium nitrate, which had supplied over 50% of global needs pre-war.[21] German facilities, scaling Haber-Bosch output to over 100,000 tons of ammonia annually by 1918, enabled continued explosive production despite the embargo, averting collapse in artillery shell manufacturing.[22] Allied powers, including the United States, responded with their own synthetic initiatives; in 1918, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers initiated the Muscle Shoals facility in Alabama to produce 60,000 tons of ammonium nitrate yearly via cyanamide and later Haber methods, though full operation post-dated the armistice.[23] These wartime imperatives demonstrated synthetic nitrates' strategic value for geopolitical stability, as unrestricted access to nitrogen compounds proved decisive in sustaining prolonged conflict. By the 1920s, synthetic production displaced natural mining, with global ammonia capacity exceeding 1 million tons annually by 1925 and Chilean exports plummeting from 2.5 million tons in 1920 to under 500,000 tons by 1930.[21] This transition correlated with agricultural yield surges during the Green Revolution (1940s–1960s), where synthetic nitrogen fertilizers—derived from ammonia—boosted global cereal production by over 200%, supporting population growth from 2.5 billion to 4 billion without proportional arable land expansion.[24] The engineering breakthroughs in catalysis and process scaling thus ensured long-term material and food security, rendering natural deposits marginal.[25]Chemical Fundamentals

Molecular Structure and Bonding

The nitrate ion (NO₃⁻) is a polyatomic anion featuring a central nitrogen atom bonded to three oxygen atoms, exhibiting trigonal planar geometry with D_{3h} point group symmetry.[26] This configuration arises from the valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory, where the nitrogen has three bonding domains and no lone pairs, yielding AX₃ electron geometry and bond angles of 120°.[26] The three N-O bonds are equivalent, each measuring 1.238 Å experimentally, as determined from rotational spectroscopy.[26] Lewis structures represent canonical resonance forms with one N=O double bond and two N-O⁻ single bonds, but the actual bonding involves delocalized π electrons across the N-O framework, resulting in partial double-bond character for all bonds and fractional formal charges (nitrogen +1, each oxygen -2/3).[27] This delocalization stabilizes the ion through electron sharing beyond localized two-center bonds.[28] The nitrogen atom employs sp² hybridization, forming three σ bonds via overlap of its sp² orbitals with oxygen p orbitals, while an unhybridized p orbital on nitrogen participates in π bonding with p orbitals on the oxygens.[29] Isotopic variants, such as those enriched with ¹⁵N, retain identical electronic and geometric structure but enable tracing in biogeochemical studies due to mass differences affecting spectroscopic signatures.[30]Physical and Chemical Properties

The nitrate ion (NO₃⁻) imparts characteristic properties to its salts, which are generally colorless or white crystalline solids at standard temperature and pressure. These salts exhibit exceptionally high solubility in water, a trait stemming from the ion's ability to form strong hydration shells via hydrogen bonding and ion-dipole interactions. Solubility values for alkali and alkaline earth nitrates often exceed 50 g/100 mL, with few exceptions among inorganic nitrates showing limited solubility, such as certain basic or hydrated forms of heavy metal nitrates.[1]/Equilibria/Solubilty/Solubility_Rules) Specific examples illustrate this trend: sodium nitrate (NaNO₃) dissolves at 88 g/100 mL at 20°C, while calcium nitrate tetrahydrate reaches over 120 g/100 mL under similar conditions. Silver nitrate (AgNO₃), though highly soluble at 222 g per 100 g water at 20°C, contrasts with the insolubility of silver halides, highlighting nitrate's role in enabling aqueous processing of otherwise precipitating ions. These solubilities increase with temperature, reflecting endothermic dissolution processes governed by lattice energy and hydration enthalpy balances.[31][32][33] Chemically, nitrates function as potent oxidants owing to nitrogen's +5 oxidation state, facilitating electron acceptance in redox reactions. Reduction typically proceeds stepwise to nitrite (NO₂⁻) via NO₃⁻ + 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → NO₂⁻ + H₂O, with a standard potential of approximately +0.94 V in acidic media, though kinetics vary with pH, reductant strength, and catalysts. Strong reducing agents like metals (e.g., copper in nitric acid) accelerate this, yielding NO or N₂O alongside nitrite, while milder conditions favor partial reduction.[34] Thermal decomposition exemplifies oxidative behavior, with most metal nitrates breaking down between 300–500°C to metal oxides (or nitrites for alkali salts), NO₂, and O₂. For potassium nitrate, initial decomposition to nitrite occurs above 550°C: 2KNO₃ → 2KNO₂ + O₂, an equilibrium shifting with temperature and influenced by autocatalytic NO₂ release. Reaction rates follow Arrhenius kinetics, with activation energies around 200–250 kJ/mol for alkali nitrates, underscoring their utility in pyrotechnics despite sensitivity to impurities.[35][36]Natural Occurrence and Biogeochemistry

Geological and Atmospheric Sources

Nitrate occurs naturally in geological deposits primarily through microbial oxidation of organic nitrogen compounds and accumulation in arid environments. In cave systems, nitrates form from the decomposition of bat guano, where ammonia is oxidized to nitric acid and combines with minerals to produce salts such as calcium nitrate; such deposits have been documented in the United States and other regions with significant bat populations.[37] Soil and evaporite deposits also contain nitrates from similar biogenic processes, though concentrations vary widely based on local aridity and organic input. The most extensive geological nitrate accumulations are found in the Atacama Desert of Chile, where caliche layers—crustal evaporites—historically contained over 10% sodium nitrate (NaNO₃) by weight, formed via long-term atmospheric deposition and minimal leaching in hyper-arid conditions.[37][38] Atmospheric sources contribute nitrates through abiotic fixation processes. Lightning discharges globally fix approximately 5 teragrams (Tg) of nitrogen per year into oxides of nitrogen (NOx), which oxidize to nitric acid (HNO₃) in the atmosphere and deposit as nitrates via precipitation, enhancing pre-industrial soil fertility.[39] Volcanic activity similarly produces nitrates, with explosive eruptions generating lightning that fixes nitrogen into deposits preserved in ash layers, and some volcanoes emitting HNO₃ vapor directly; however, volcanic contributions remain minor relative to lightning on a global scale.[40][41] In natural water systems, these sources establish low baseline nitrate levels absent significant anthropogenic influence. Pristine groundwater aquifers typically exhibit concentrations below 1 mg/L nitrate-nitrogen, reflecting limited natural inputs from atmospheric deposition and geological weathering.[42] Oceanic surface waters similarly maintain low nitrates, often under 1 μM (approximately 0.06 mg/L as N) in nutrient-depleted zones, with deeper waters reaching 20-40 μM due to remineralization, providing a causal reference for undisturbed biogeochemical baselines.[43]Nitrogen Cycle Integration

In the nitrogen cycle, nitrification transforms reduced nitrogen compounds, primarily ammonium (NH₄⁺), into nitrate (NO₃⁻) through sequential microbial oxidation under aerobic conditions. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria such as Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira first convert ammonium to nitrite (NO₂⁻), followed by nitrite-oxidizing bacteria like Nitrobacter and Nitrospira oxidizing nitrite to nitrate.[44][45] This two-step autotrophic process is chemolithotrophic, deriving energy from the oxidation reactions, and proceeds optimally at near-neutral soil pH (around 7–8) and sufficient oxygen levels, with rates declining in acidic or anaerobic environments due to inhibited bacterial activity.[46] Nitrification generates nitrate as a highly soluble, mobile anion that facilitates nitrogen transport through soil pore water, enabling diffusion to plant roots and preventing localized nitrogen depletion in aerobic ecosystems.[47] Denitrification counterbalances nitrification by reducing nitrate back to dinitrogen gas (N₂) under low-oxygen conditions, primarily via heterotrophic bacteria such as Pseudomonas and Paracoccus species, which use nitrate as an electron acceptor in anaerobic respiration.[48] The process sequentially produces nitrite, nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N₂O), and finally N₂, with rates accelerated by low oxygen availability, neutral to alkaline pH, and ample organic carbon substrates that drive microbial demand.[49] These transformations form a closed-loop dynamic where nitrate serves as a transient, oxidized intermediate, recycled through microbial consortia to maintain nitrogen availability without indefinite accumulation, contrasting models that treat nitrate solely as a pollutant endpoint. Global biological nitrogen fixation inputs approximately 90–130 Tg N per year into terrestrial and aquatic systems, with nitrification-denitrification fluxes ensuring nitrate's role in averting widespread nitrogen limitation by mobilizing fixed nitrogen for biotic uptake.[50] Plants have evolved specialized high-affinity nitrate transporters, particularly from the NRT2 family, to efficiently acquire nitrate at low soil concentrations typical of natural ecosystems. These proton-coupled symporters, often requiring partner proteins like NAR2, enable root uptake under nitrogen-scarce conditions, reflecting adaptations during plant terrestrialization to exploit patchy nitrate distributions.[51] Empirical studies show such transporters sustain growth in oligotrophic soils by prioritizing nitrate over ammonium assimilation, linking microbial nitrate production directly to plant nitrogen demands and perpetuating cycle efficiency through root exudates that stimulate rhizosphere nitrifiers.[52]Production Methods

Extraction from Natural Deposits

The primary geological sources of nitrates for extraction are the vast caliche deposits in Chile's Atacama Desert, which contain sodium nitrate (NaNO₃) at concentrations of 5-25% alongside other salts like sulfates and perchlorates.[15] Open-pit mining techniques dominate, involving excavation of the surface layer, crushing the ore to increase surface area, and selective leaching with heated water or brine (typically at 35-50°C) to dissolve the soluble nitrates while leaving insoluble gangue behind.[53] The pregnant leach solution is then filtered, cooled to below 20°C to promote crystallization of sodium nitrate, and the crystals are centrifuged, washed, and dried for purity levels exceeding 99%.[54] This process, refined in the late 19th century, optimized yields from low-grade ores but required vast water inputs in an arid environment, often sourced via pipelines from coastal desalination or imported supplies.[55] Historical production from Atacama deposits escalated rapidly after 1880, peaking at nearly 3 million metric tons of sodium nitrate annually around 1913, equivalent to about 700,000 tons of nitrogen and supplying over 80% of global demand for fertilizers and explosives.[21] Output in the 1900-1910 period averaged 2-2.5 million tons per year, driven by expanding rail infrastructure and oficina processing plants that integrated mining with on-site leaching facilities, though economic viability hinged on nitrate prices above $50 per ton (1910 dollars) to cover labor and transport costs.[56] Known reserves exceeded 100 million tons of recoverable nitrates by the early 20th century, suggesting physical depletion timelines of decades at peak rates, but selective high-grade extraction progressively lowered ore quality, raising processing costs by 20-30% over time.[15] Potassium nitrate (KNO₃), or saltpeter, was extracted historically from artificial nitre beds rather than large geological deposits, a method prevalent in 18th-century Europe and India for gunpowder production. In Europe, beds consisted of layered heaps (up to 5 meters high) of manure, straw, soil, and lime or wood ashes to foster bacterial oxidation of organic nitrogen to nitrates over 1-2 years, followed by hot-water leaching, filtration through ash for potassium exchange, and boiling to crystallize the product at yields of 1-5% nitrate by weight from the compost mass. Indian methods relied on nitrified earth from stables or natural saline soils, scraped, leached in pits, and purified via solar evaporation, producing higher-purity saltpeter (up to 90% KNO₃) but at smaller scales of hundreds of tons annually per region.[57] These low-efficiency processes, requiring manual labor and land for beds, yielded insufficient volumes for industrial agriculture, limiting economic viability to military needs until synthetic alternatives emerged.[58] Extraction from natural deposits became uneconomical post-1920s as synthetic ammonia production via the Haber-Bosch process scaled to exceed natural output by 1930, with Chilean nitrate exports collapsing from 2.5 million tons in 1920 to under 500,000 tons by 1930 amid price drops over 60%.[59] Remaining operations in Atacama focus on iodine co-recovery from caliche, yielding nitrates as a minor by-product (tens of thousands of tons annually) for premium markets like organic fertilizers, where natural sourcing commands 20-50% price premiums despite higher extraction costs.[60] Untapped reserves persist, but full depletion timelines extend centuries at current residual rates, constrained more by market competition than resource exhaustion.[15]Industrial Synthesis Processes

The principal industrial route to nitrates involves the synthesis of nitric acid through the Ostwald process, followed by neutralization reactions to produce various nitrate salts such as ammonium nitrate. In the Ostwald process, anhydrous ammonia is catalytically oxidized with air over a platinum-rhodium gauze catalyst at temperatures of 850–950°C to form nitric oxide (NO), which is then oxidized to nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) at lower temperatures and absorbed into water to yield nitric acid (HNO₃). Modern facilities achieve nitric acid yields of 96–99% relative to ammonia feedstock, reflecting optimizations in catalyst selectivity and absorption efficiency.[61][20] The process is energetically favorable due to the exothermic oxidation steps, with contemporary dual-pressure plants typically exporting surplus steam energy equivalent to 8–11 GJ per metric ton of 100% HNO₃ produced, after accounting for compression and other inputs; gross energy demands, including auxiliary systems, remain below 3 GJ/ton in efficient operations.[62][61] This efficiency underscores scalable resource conversion, enabling high-volume output with minimal net energy import beyond the ammonia precursor. Ammonium nitrate, a key nitrate compound, is synthesized by reacting 50–60% nitric acid with excess anhydrous ammonia in a continuous neutralization reactor, yielding a hot ammonium nitrate solution (typically 80–83% concentration) that undergoes evaporation, cooling, and solidification via prilling or granulation to form porous or dense solids.[63][64] The reaction is highly exothermic, facilitating self-sustaining concentration, with overall ammonia-to-product nitrogen recovery exceeding 99% in integrated plants. Other nitrates, such as calcium or potassium nitrate, follow analogous acid-base neutralization using the respective bases, often in batch or continuous modes tailored to purity requirements. Post-2000 advancements have focused on emission controls and process intensification, including extended platinum catalysts for higher ammonia conversion (up to 99.5%) and integrated selective catalytic reduction (SCR) units that decompose N₂O to N₂ and O₂ with 90–99% efficiency, alongside NOx abatement to below 50–200 mg/Nm³ via non-selective catalytic reduction or EnviNOx systems.[65][61] These catalytic refinements, coupled with oxygen enrichment in select absorbers, have halved NOx release in retrofitted plants while boosting capacity by 10–20%, demonstrating iterative engineering gains in yield and environmental footprint without compromising throughput.[66][67]Analytical Detection

Laboratory Techniques

One standard laboratory technique for nitrate quantification involves cadmium reduction of nitrate to nitrite, followed by the Griess diazotization reaction for colorimetric detection. In this method, samples are passed through a cadmium column or amalgam to convert nitrate quantitatively to nitrite, which then reacts with sulfanilamide and N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride under acidic conditions to form a pink azo dye measured spectrophotometrically at approximately 540 nm.[68] This approach achieves a limit of detection (LOD) of about 0.1 mg/L as nitrate-nitrogen, with linear response up to 10 mg/L, though it requires careful handling of cadmium due to its toxicity and potential for column clogging from particulates.[69] Validation studies confirm precision within 5% relative standard deviation for concentrations above 0.5 mg/L in reagent water.[68] Ion chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection provides a direct separation and quantification of nitrate among other anions, as outlined in EPA Method 300.1. Samples are injected into a high-pressure liquid chromatography system using an anion-exchange column (e.g., quaternary ammonium functional groups) and a carbonate-bicarbonate eluent, with post-column suppression to enhance conductivity signals for nitrate peaks eluting around 5-10 minutes depending on column specifics.[70] Detection limits reach 0.1-1 μg/L for nitrate in clean matrices, enabling analysis of low-level samples without chemical reduction, though matrix effects like high sulfate can require dilution or gradient elution for optimal resolution.[70] This method's specificity stems from chromatographic separation, minimizing interferences from nitrite or chloride when standards are matrix-matched.[71] Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy offers a non-destructive alternative by exploiting nitrate's strong absorption peak at 220 nm, with a secondary band at 275 nm used for baseline correction against organic matter interference.[72] Calibration follows Beer's law linearly up to 11 mg/L nitrate-nitrogen, but the technique's LOD is typically 0.5-1 mg/L due to spectral overlap with dissolved organics or humic substances, limiting reliability in unfiltered or complex lab samples without prior purification.[72][73] Validated against reference standards, it suits controlled laboratory settings but demands dual-wavelength ratios (220/275 nm) for accuracy, as single-wavelength readings overestimate in turbid media.[74]Environmental Monitoring Methods

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) enable direct in-situ measurement of nitrate concentrations in soil pore water and surface runoff, facilitating real-time assessment of agricultural nutrient dynamics without extensive sample preparation. These probes typically achieve measurement accuracy within ±5% relative to laboratory standards when calibrated against known solutions, as demonstrated in field studies of fertilizer leaching. In agricultural runoff monitoring, ISEs have been deployed in cooperative networks to quantify nitrate export from tile-drained fields, revealing peak concentrations exceeding 10 mg/L NO₃-N during storm events linked to recent manure application.[75][76] Satellite-based remote sensing, particularly hyperspectral imaging, supports large-scale nitrate tracking in aquatic environments by inverting ocean color reflectance data through bio-optical algorithms. Recent advancements, including machine learning models integrated with Copernicus Marine Service datasets, reconstruct surface and subsurface nitrate fields with resolutions down to 1 km, enabling inference of upwelling-driven elevations up to 5 μM in productive coastal zones from 2023 onward. These methods correlate nitrate anomalies with chlorophyll-a patterns, aiding causal analysis of nutrient inputs from riverine discharge rather than relying on fixed thresholds. Validation against in-situ profiles shows root-mean-square errors below 2 μM for open-ocean estimates.[77][78] Enzymatic biosensors, employing nitrate reductase immobilized on nanomaterials, provide rapid, selective detection of soil nitrate for precision agriculture applications, with response times under 5 minutes and limits of detection around 0.1 mg/kg. Integrated into portable devices, these sensors map spatial variability in root-zone nitrate, supporting variable-rate fertilization decisions that reduce over-application by 20-30% based on field trials. Their specificity minimizes interference from humic substances common in soils, outperforming non-enzymatic alternatives in heterogeneous matrices.[79][80]Applications and Uses

Agricultural Fertilizers

Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, including nitrate-containing forms such as ammonium nitrate, have enabled dramatic increases in global crop productivity by addressing nitrogen limitations in soils. During the Green Revolution spanning the 1960s to 2000, cereal crop production in developing countries tripled while cultivated land area expanded by only 30%, with synthetic fertilizers contributing substantially to yield gains alongside high-yielding varieties; this expansion supported a doubling of population without corresponding famines in key regions like Asia.[81] Ammonium nitrate and urea— the latter converting to ammonium and subsequently nitrate via soil nitrification—together dominate global nitrogen inputs, with urea accounting for over half of nitrogen fertilizer production due to its high nitrogen content (46%) and cost-effectiveness.[24] These inputs supply roughly 50% of the nitrogen harvested in crops worldwide, far exceeding natural fixation rates that historically constrained yields to subsistence levels.[82] Optimal application rates for cereals typically range from 100 to 250 kg N per hectare, depending on crop type, soil conditions, and region; for instance, winter wheat often requires around 230 kg N/ha to achieve maximum yields in temperate zones.[83] While nitrogen use efficiency averages 30-50%, with losses including 20-60% via leaching under suboptimal conditions, the causal link to yield boosts remains robust, as fertilized systems produce 2-3 times more caloric output per hectare than unfertilized counterparts, yielding positive returns on investment for food security.[84] Site-specific management, which tailors rates to soil variability and crop needs using tools like management zones, empirically counters critiques of uniform over-application by enhancing efficiency and minimizing excess without sacrificing productivity.[85] In contrast to natural biogeochemical cycles, where symbiotic fixation and mineralization supply only 10-20 kg N/ha annually—insufficient for intensive cropping—nitrate-delivery fertilizers enable scalable agriculture that has sustained billions, prioritizing empirical yield data over generalized efficiency concerns.[86] Ongoing refinements, such as precision application of ammonium nitrate solutions, further amplify these gains by reducing volatilization and synchronizing supply with plant uptake.[87]Explosives and Military Applications

Nitrates serve as primary oxidizers in explosives due to their ability to rapidly release oxygen, facilitating combustion or detonation in oxygen-deficient mixtures. In traditional black powder, the earliest military propellant, potassium nitrate (KNO₃) constitutes approximately 75% by weight, combined with 15% charcoal and 10% sulfur, enabling deflagration for firearms and artillery from the 13th century onward.[88] This formulation's efficacy stemmed from nitrate's provision of oxygen to sustain rapid burning, achieving burn rates suitable for propelling projectiles, though limited to subsonic velocities around 300-400 m/s.[89] During World War I, Allied forces relied heavily on Chilean sodium nitrate deposits for producing nitric acid and nitrates essential for high explosives like ammonium nitrate-based compounds and cordite propellants, supporting massive artillery barrages that exceeded 1 million shells per day at peak.[90] Germany's naval blockade disrupted global nitrate shipping, prompting the Haber-Bosch process—implemented by 1913—to synthesize ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen, subsequently oxidized to nitric acid for domestic explosive production, averting supply shortages.[23] Post-war adoption of synthetic methods globally eliminated dependency on natural deposits, ensuring reliable scaling for military needs without geopolitical vulnerabilities.[91] Contemporary military applications favor ammonium nitrate (NH₄NO₃)-based mixtures like ANFO, typically 94% prilled ammonium nitrate sensitized with 6% fuel oil, yielding detonation velocities of 3.2-5 km/s depending on confinement and density, ideal for large-scale breaching and demolition.[92] Ammonium nitrate's thermal stability—decomposing only above 170°C under melting, with explosive potential requiring sensitizers and confinement—allows safe handling in military logistics, though incidents like unintended detonations underscore the need for precise engineering to control decomposition thresholds.[93] These properties underpin nitrates' enduring role in propellants, balancing high energy release with manageable safety profiles through additives that lower activation energy without compromising oxidative power.[92]Industrial and Chemical Processes

Nitric acid, the primary industrial nitrate derivative, is produced globally at approximately 58 million tonnes annually as of 2024, primarily via the Ostwald process involving ammonia oxidation.[94] Around 5-10% of this output is directed toward organic synthesis, including the oxidation of cyclohexane or cyclohexanol/cyclohexanone mixtures to adipic acid, a key monomer for nylon-6,6 production.[95] This two-stage nitric acid oxidation process typically employs 50-70% HNO₃ concentrations under controlled temperatures of 75-90°C, yielding adipic acid alongside by-products like nitrous oxide.[96] Nitrates and nitric acid serve as oxidizing agents in metal processing, particularly for etching and pickling stainless steel to remove oxide scales and enhance corrosion resistance.[97] In steel pickling, mixtures of 10-40% nitric acid with hydrofluoric acid dissolve surface contaminants, with nitric acid concentrations optimized to 20-30% for effective oxide removal without excessive base metal attack; this application consumes several million tonnes of nitric acid yearly, though alternatives like sulfuric acid are increasingly adopted to minimize NOx emissions.[98] Nitric acid also etches copper, brass, and silver in precision manufacturing, where diluted solutions (10-50%) create controlled surface textures or patterns.[99] In pyrotechnics, nitrate salts such as potassium nitrate (KNO₃) and barium nitrate (Ba(NO₃)₂) function as oxidizers, providing oxygen for combustion while contributing color; barium nitrate, for instance, imparts green hues in fireworks formulations comprising 20-50% nitrate content by weight.[100] These compounds enable rapid energy release in black powder and specialty effects, with global pyrotechnic demand driving steady nitrate consumption despite regulatory scrutiny on emissions. Silver nitrate (AgNO₃) has historically been integral to photographic emulsions, where it reacts with halides in gelatin to form light-sensitive silver salts for film and paper coatings; production peaked mid-20th century at thousands of tonnes annually before digital imaging reduced demand by over 90% since the 1990s.[101] Residual industrial use persists in specialty analog processes, but volumes remain minimal compared to peak eras.[102]Medical and Pharmaceutical Roles

Organic nitrates, such as nitroglycerin (glyceryl trinitrate), have been employed in cardiovascular medicine since the late 19th century for their vasodilatory properties. Synthesized in 1847, nitroglycerin was first applied clinically for angina pectoris by William Murrell in 1879, building on earlier observations of its effects in alleviating chest pain through vascular relaxation.[103][104] These compounds act as exogenous donors of nitric oxide (NO), which diffuses into vascular smooth muscle cells to activate soluble guanylate cyclase, elevating cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels and promoting dephosphorylation of myosin light chains, thereby inducing venodilation and reducing cardiac preload.[105][106] This mechanism decreases myocardial oxygen demand, providing rapid relief in acute angina episodes without significantly impacting afterload at low doses.[107] For acute angina management, sublingual nitroglycerin tablets are administered at doses of 0.3–0.6 mg, placed under the tongue at the onset of symptoms, with repeat dosing every 5 minutes up to three times if needed, yielding relief within minutes via swift absorption and NO-mediated coronary vasodilation.[108][109] Clinical guidelines affirm this approach's efficacy in stable angina, supported by over a century of use demonstrating improved exercise tolerance and symptom control.[110] Prolonged-release formulations, like isosorbide dinitrate, extend therapeutic effects for chronic prophylaxis, though tolerance can develop with continuous exposure due to impaired biotransformation.[105] In hypertension management, dietary nitrate supplementation—often via concentrated beetroot juice providing 5–10 mmol of nitrate—has shown blood pressure-lowering effects in recent clinical trials, converting to nitrite and NO via the enterosalivary pathway to enhance endothelial function and vasodilation. A 2024 randomized controlled trial in 68 hypertensive patients reported a mean systolic blood pressure reduction of 9.0 mmHg after 4 weeks of nitrate-replete beetroot juice.[111] Similarly, a 2025 study in older adults linked nitrate-rich beetroot juice to microbiome-mediated systolic drops of 5–10 mmHg, with dose-dependent plasma nitrate elevations correlating to vascular improvements.[112][113] These findings, from meta-analyses of over 2,000 participants, indicate modest but consistent ambulatory reductions, particularly in systolic pressure, positioning nitrate supplementation as an adjunctive, non-pharmacological intervention.[114] Topical nitrate formulations, including nitroglycerin gels or acidified nitrite solutions, promote wound healing by locally generating NO to stimulate angiogenesis, collagen deposition, and antimicrobial activity without substantial systemic exposure. In diabetic rat models, a 1% carbopol-based nitroglycerin gel with aloe vera accelerated incisional wound closure compared to controls, attributed to enhanced perfusion and reduced inflammation.[115] Human pharmacokinetic data from topical sodium nitrite applications in chronic ulcers confirm minimal absorption, with plasma levels remaining below toxic thresholds, enabling safe localized NO delivery for impaired healing in conditions like sickle cell disease or diabetes.[116][117]Human Health Implications

Dietary Nitrate Sources

Dietary nitrates primarily enter human diets through plant-based foods, which account for approximately 80-85% of total intake in Western populations. Vegetables, particularly leafy greens and root crops, are the dominant sources due to nitrate accumulation from soil uptake via fertilizers and natural processes. For instance, beetroot contains 110-250 mg of nitrate per 100 g fresh weight, while spinach provides 200-400 mg per 100 g, with variations depending on cultivation conditions such as soil nitrogen levels and harvest timing.[118][119] Other high-nitrate vegetables include arugula (up to 480 mg/100 g), celery, and lettuce, contributing significantly to daily exposure through salads, juices, and cooked dishes.[120][121] Processed meats, such as bacon and ham, represent a secondary vector, where sodium nitrite (NaNO₂) is added as a preservative and partially converts to nitrate during curing and storage. However, cured meats contribute only about 5% of total dietary nitrate, with residual levels typically below 100 mg/kg in finished products, far lower than vegetable concentrations on a per-weight basis.[122][123] Fresh meats contain negligible nitrates, as transfer from animal feed (e.g., nitrate-rich forages) to muscle tissue is minimal, with residues rarely exceeding regulatory limits of 2-10 mg/kg due to efficient metabolism in livestock.[124][125] Average daily nitrate intake in Western diets ranges from 50-140 mg, predominantly from vegetable consumption, with bioavailability exceeding 90% for plant-derived forms due to efficient gastrointestinal absorption.[126][127] Drinking water and other non-vegetable sources add 10-20% but remain minor compared to produce. Updated analyses confirm vegetables as 76-83% of intake, underscoring their role over processed or animal-derived origins.[128][129]Beneficial Physiological Effects

Dietary nitrate, primarily from vegetable sources such as beetroot and leafy greens, undergoes enterosalivary circulation wherein ingested nitrate is concentrated in saliva and reduced to nitrite by oral bacteria, particularly species like Veillonella and Actinomyces, which possess nitrate reductase enzymes.[130] This nitrite is then swallowed, absorbed, and further converted to nitric oxide (NO) in hypoxic or acidic environments, such as the stomach or vascular tissues, facilitating NO-mediated signaling independent of the canonical endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway.[131] Randomized controlled trials demonstrate dose-dependent increases in plasma nitrite and NO bioavailability following nitrate supplementation, with typical effective doses of 5-10 mmol (e.g., 250-500 mL beetroot juice) yielding measurable physiological responses within 2-3 hours.[113] The resultant NO promotes vasodilation via smooth muscle relaxation and cGMP elevation, leading to reduced blood pressure; an umbrella review of 113 randomized trials encompassing over 2,000 participants reported average reductions of 4.4 mmHg in systolic blood pressure and 1.1 mmHg in diastolic blood pressure with dietary nitrate supplementation, effects comparable to pharmacological interventions and sustained across normotensive and hypertensive cohorts.[114] These benefits are attributed to enhanced endothelial function, where circulating nitrite serves as a reservoir for NO production, improving flow-mediated dilation by 1-2% in meta-analyzed supplementation studies.[113] In exercise physiology, nitrate supplementation augments mitochondrial efficiency and oxygen utilization, evidenced by meta-analyses of randomized trials showing 3-5% improvements in time-to-exhaustion during moderate-intensity endurance tasks and reduced oxygen cost of submaximal exercise, though peak VO2 max enhancements are inconsistent and typically modest (0-3%).[132] Dose-response data from acute trials indicate optimal effects with 6-12 mmol nitrate, correlating with elevated plasma nitrite and improved muscle perfusion during incremental workloads.[133] Emerging evidence from observational cohorts links habitual plant-derived nitrate intake to neuroprotective outcomes, including lower cerebral β-amyloid deposition and hippocampal volume preservation in Alzheimer's disease markers, potentially via NO-mediated cerebral vasodilation and anti-inflammatory effects; however, causal supplementation trials remain limited, with animal models demonstrating myelin preservation and cognitive amelioration through sialin upregulation and TPPP inhibition.[134] Human randomized studies hypothesize endothelial nitrite reservoirs mitigate neurodegeneration by sustaining brain perfusion, though long-term trial data are pending confirmation beyond associative epidemiology.[135]Toxicity Mechanisms and Risks

Nitrate toxicity primarily manifests through its reduction to nitrite, which impairs oxygen transport in blood via methemoglobin formation, particularly in vulnerable populations such as infants. In the gastrointestinal tract, nitrate is converted to nitrite by microbial enzymes, and excess nitrite oxidizes the ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) in hemoglobin to ferric iron (Fe³⁺), forming methemoglobin that cannot bind oxygen effectively, leading to tissue hypoxia.[136] Infants under 4 months are especially susceptible due to immature methemoglobin reductase activity, which reduces methemoglobin back to hemoglobin, and higher gastric pH that favors nitrate-reducing bacteria.[137] This condition, known as blue baby syndrome, occurs at nitrate concentrations exceeding 10 mg/L in drinking water, primarily from contaminated wells used in formula preparation, though cases are exceedingly rare in regions with treated municipal water supplies, representing less than 1% of infant formula exposures in documented outbreaks.[138][139] Acute oral toxicity of nitrate salts like sodium nitrate exhibits an LD50 of approximately 1.3 g/kg in rats, with human estimates suggesting a probable lethal dose of 0.5-5 g/kg body weight, far exceeding typical dietary intakes.[140] Symptoms include cyanosis, hypotension, and coma at high doses, but survival is common below these thresholds due to rapid urinary excretion and endogenous conversion pathways.[141] Chronic exposure risks are dose-dependent and modulated by co-factors; for instance, nitrite-derived nitrosamines form via reaction with secondary amines in acidic environments, potentially initiating carcinogenesis through DNA alkylation.[142] In processed meats, added nitrates and nitrites contribute to N-nitrosamine formation during curing and cooking, with the International Agency for Research on Cancer classifying processed meat as a Group 1 carcinogen partly due to this pathway, linked to increased colorectal and stomach cancer risks in epidemiological data.[143] However, this risk is context-specific: vegetable-derived nitrates show an inverse association with cancer due to inhibitory antioxidants like vitamin C that block nitrosation, highlighting a source-dependent paradox where the food matrix determines net harm rather than nitrate alone.[144] Recent reviews emphasize that chronic risks from dietary nitrates are often overstated without accounting for such confounders, as plant sources predominate in intakes and correlate with cardiovascular benefits outweighing rare oncogenic events at moderate levels.[144][145]Environmental Dynamics

Ecosystem Nutrient Role

Nitrate functions as an essential nutrient in ecosystem trophic dynamics, serving as the primary bioavailable form of nitrogen assimilated by primary producers such as algae, aquatic macrophytes, and terrestrial plants, thereby driving photosynthetic productivity and supporting higher trophic levels. In freshwater ecosystems, nitrate often limits growth due to its role in stoichiometric balances, with empirical ratios approximating the Redfield N:P atomic ratio of 16:1, below which nitrogen scarcity constrains algal and plant biomass accumulation. This limitation underscores nitrate's regulatory influence on primary production, where pulsed availability enhances carbon fixation and energy transfer through food webs, countering narratives that frame nitrate predominantly as an excess rather than a foundational input.[146][147][148] Natural inputs of nitrate occur via biological nitrogen fixation, where diazotrophic bacteria and cyanobacteria convert atmospheric dinitrogen into ammonium and subsequently nitrate through nitrification, generating episodic pulses that alleviate nutrient deficits and foster biodiversity by enabling transient booms in producer populations and associated herbivores. These fixation-driven enrichments, estimated to contribute 100-200 Tg N annually globally in natural systems, structure community dynamics without inducing chronic imbalances, as evidenced by resilient productivity in pre-human disturbance habitats. Denitrifying bacteria then mediate feedback by reducing nitrate to N₂ under anoxic conditions, restoring nitrogen equilibrium and preventing indefinite accumulation even amid variable fixation rates.[149][150] In undisturbed watersheds, baseline nitrate concentrations in rivers typically ranged from 0.1 to 1 mg/L, levels sufficient to sustain fish yields and invertebrate assemblages without hypoxia primarily linked to nitrogen alone, as oxygen depletion requires concurrent organic loading and phosphorus co-limitation. Anthropogenic nitrogen additions amplify these fluxes but interact with denitrification's capacity to modulate net retention, illustrating closed-system homeostasis where microbial processes cap excesses absent external exports. Such dynamics highlight nitrate's integral role in maintaining trophic stability, with empirical productivity responses in nitrogen-limited lakes showing 2-5 fold biomass increases upon modest nitrate supplementation under controlled conditions.[151][152][153]Pollution Pathways and Eutrophication

Nitrate pollution primarily enters aquatic systems through leaching from agricultural soils, where excess nitrogen from fertilizers and manure percolates beyond root zones into groundwater, subsequently discharging into rivers and coastal waters. In intensive cropping systems, leaching losses typically range from 10% to 30% of applied nitrogen, depending on soil type, rainfall, and management practices, with higher rates observed under over-application or during wet periods. Tile drainage systems, prevalent in regions like the U.S. Midwest, accelerate this process by rapidly conveying subsurface water to streams, contributing 44% to 82% of watershed nitrate exports in studied Iowa basins. Surface runoff during storms also transports dissolved and particulate nitrates, though leaching dominates in permeable soils. These nitrates, often in combination with phosphorus from similar anthropogenic sources, drive eutrophication by fueling excessive algal growth in receiving waters. Algal blooms deplete oxygen upon decomposition, creating hypoxic zones that suffocate fish and disrupt ecosystems; the process is multifactorial, requiring both nitrogen and phosphorus enrichment alongside physical factors like water stratification. In the Gulf of Mexico, fed by the Mississippi River, this manifests as seasonal "dead zones" averaging around 4,755 square miles over recent five-year periods, with the 2025 measurement at approximately 4,402 square miles—below average but still indicative of persistent nutrient loading. Agricultural runoff accounts for the majority of riverine nitrate inputs in the U.S., particularly from the Corn Belt, though atmospheric deposition contributes 10% to 30% via wet and dry fallout from emissions, and natural sources like soil mineralization add baseline levels modulated by weather variability. Critics of stringent nitrate restrictions argue that alarmist narratives overlook trade-offs with food security, as nitrogen fertilizers have enabled yield doublings since the mid-20th century, averting famines in a growing global population. Empirical evidence supports precision technologies, such as variable-rate nitrogen application guided by soil sensors and remote sensing, which can reduce excess inputs and associated losses by up to 15% without compromising harvests, thereby balancing productivity needs against environmental risks. In Iowa, where tile drainage amplifies exports during high-precipitation years, interannual variability underscores that not all loading stems from mismanagement, with fallow periods and storms exacerbating natural mobilization.[154][155][156][157][158][159]Regulatory Frameworks and Debates