Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Abner

View on Wikipedia

In the Hebrew Bible, Abner (Hebrew: אַבְנֵר ʾAḇnēr) was the cousin of King Saul and the commander-in-chief of his army.[1] His name also appears as אבינר בן נר "Abiner son of Ner", where the longer form Abiner means "my father is Ner".[2]

Biblical narrative

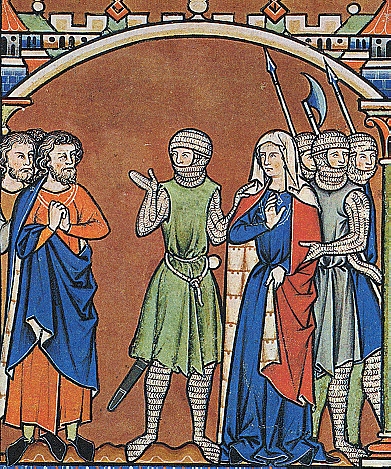

[edit]Abner is initially mentioned incidentally in Saul's history,[3] first appearing as the son of Ner, Saul's uncle, and the commander of Saul's army. He then comes to the story again as the commander who introduced David to Saul following David's killing of Goliath. He is not mentioned in the account of the disastrous battle of Gilboa when Saul's power was crushed. Seizing the youngest but only surviving of Saul's sons, Ish-bosheth, also called Eshbaal, Abner set him up as king over Israel at Mahanaim, east of the Jordan. David, who was accepted as king by Judah alone, was meanwhile reigning at Hebron, and for some time war was carried on between the two parties.[4]

The only engagement between the rival factions told at length was preceded by an encounter at Gibeon between 12 chosen men from each side, in which all 24 seem to have perished.[5][a] In the general engagement which followed, Abner was defeated and put to flight. He was closely pursued by Asahel, brother of Joab, who is said to have been "light of foot as a wild roe".[6] As Asahel would not desist from the pursuit, though warned, Abner was compelled to slay him in self-defense, planting his spear in the ground and allowing Asahel to impale himself. This originated a deadly feud between the leaders of the opposite parties, for Joab, as next of kin to Asahel, was by the law and custom of the country the avenger of his blood.[4] However, according to Josephus, in Antiquities, book 7, chapter 1, Joab had forgiven Abner for the death of his brother, Asahel, the reason being that Abner had slain Asahel honorably in combat after he had first warned Asahel and tried to knock the wind out of him with the butt of his spear.

For some time afterward, the war was carried on, the advantage being invariably on the side of David. At length, Ish-bosheth lost the main prop of his tottering cause by accusing Abner of sleeping with Rizpah,[7] one of Saul's concubines, an alliance which, according to contemporary notions, would imply pretensions to the throne.[8]

Abner was indignant at the rebuke, and immediately opened negotiations with David, who welcomed him on the condition that his wife Michal should be restored to him. This was done, and the proceedings were ratified by a feast. Almost immediately after, however, Joab, who had been sent away, perhaps intentionally, returned and slew Abner at the gate of Hebron. The ostensible motive for the assassination was a desire to avenge Asahel, and this would be a sufficient justification for the deed according to the moral standard of the time (although Abner should have been safe from such a revenge killing in Hebron, which was a City of Refuge). The conduct of David after the event was such as to show that he had no complicity in the act, though he could not venture to punish its perpetrators.[9][4]

David had Abner buried in Hebron, as stated in 2 Samuel 3:31–32,[10] "And David said to all the people who were with him, 'Rend your clothes and gird yourselves with sackcloth, and wail before Abner.' And King David went after the bier. And they buried Abner in Hebron, and the king raised his voice and wept on Abner's grave, and all the people wept."[11]

Shortly after Abner's death, Ish-bosheth was assassinated as he slept,[12] and David became king of the reunited kingdoms.[13]

Rabbinical literature

[edit]Midrashic writings establish Abner as the son of the Witch of En-dor (Pirḳe R. El. xxxiii.), and the hero par excellence in the Haggadah (Yalḳ., Jer. 285; Eccl. R. on ix. 11; Ḳid. 49b). Conscious of his extraordinary strength, he exclaimed: "If I could only catch hold of the earth, I could shake it" (Yalḳ. l.c.)—a saying which parallels the famous utterance of Archimedes, "Had I a fulcrum, I could move the world." According to the Midrash (Eccl. R. l.c.) it would have been easier to move a wall six yards thick than one of the feet of Abner, who could hold the Israelitish army between his knees. Yet when his time came, Joab smote him. But even in his dying hour, Abner seized his foe like a ball of thread, threatening to crush him. Then the Israelites came and pleaded for Joab's life, saying: "If thou killest him we shall be orphaned, and our women and all our belongings will become a prey to the Philistines." Abner answered: "What can I do? He has extinguished my light" (has wounded me fatally). The Israelites replied: "Entrust thy cause to the true judge [God]." Then Abner released his hold upon Joab and fell dead to the ground (Yalḳ. l.c.).

The rabbis agree that Abner deserved this violent death, though opinions differ concerning the exact nature of the sin that entailed so dire a punishment on one who was, on the whole, considered a "righteous man" (Gen. R. lxxxii. 4). Some reproach him that he did not use his influence with Saul to prevent him from murdering the priests of Nob (Yer. Peah, i. 16a; Lev. R. xxvi. 2; Sanh. 20a)—convinced as he was of the innocence of the priests and of the propriety of their conduct toward David, Abner holding that as leader of the army David was privileged to avail himself of the Urim and Thummim (I Sam. xxii. 9–19). Instead of contenting himself with passive resistance to Saul's command to murder the priests (Yalḳ., Sam. 131), Abner ought to have tried to restrain the king. Others maintain that Abner did make such an attempt, but in vain, and that his one sin consisted in that he delayed the beginning of David's reign over Israel by fighting him after Saul's death for two years and a half (Sanh. l.c.). Others, again, while excusing him for this—in view of a tradition founded on Gen. xlix. 27, according to which there were to be two kings of the house of Benjamin—blame Abner for having prevented a reconciliation between Saul and David on the occasion when the latter, in holding up the skirt of Saul's robe (I Sam. xxiv. 11), showed how unfounded was the king's mistrust of him. Saul was inclined to be pacified; but Abner, representing to him that David might have found the piece of the garment anywhere—possibly caught on a thorn—prevented the reconciliation (Yer. Peah, l.c., Lev. R. l.c., and elsewhere). Moreover, it was wrong in Abner to permit Israelitish youths to kill one another for sport (II Sam. ii. 14–16). No reproach, however, attaches to him for the death of Asahel, since Abner killed him in self-defense (Sanh. 49a).

It is characteristic of the rabbinical view of the Bible narratives that Abner, the warrior pure and simple, is styled "Lion of the Law" (Yer. Peah, l.c.), and that even a specimen is given of a halakic discussion between him and Doeg as to whether the law in Deut. xxiii. 3 excluded Ammonite and Moabite women from the Jewish community as well as men. Doeg was of the opinion that David, being descended from the Moabitess Ruth, was not fit to wear the crown, nor even to be considered a true Israelite; while Abner maintained that the law affected only the male line of descent. When Doeg's dialectics proved more than a match for those of Abner, the latter went to the prophet Samuel, who not only supported Abner in his view, but utterly refuted Doeg's assertions (Midr. Sam. xxii.; Yeb. 76b et seq.).

One of the most prominent families (Ẓiẓit ha-Kesat) in Jerusalem in the middle of the first century of the common era claimed descent from Abner (Gen. R. xcviii.).[14]

Tomb of Abner

[edit]The site known as the Tomb of Abner is located not far from the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron and receives visitors throughout the year. Many travelers have recorded visiting the tomb over the centuries.

Benjamin of Tudela, who began his journeys in 1165, wrote in the journal, "The valley of Eshkhol is north of the mountain upon which Hebron stood, and the cave of Makhpela is east thereof. A bow-shot west of the cave is the sepulchre of Abner the son of Ner."[15]

A rabbi in the 12th century records visiting the tomb as reprinted in Elkan Nathan Adler's book Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages: 19 Firsthand Accounts.[16] The account states, "I, Jacob, the son of R. Nathaniel ha Cohen, journeyed with much difficulty, but God helped me to enter the Holy Land, and I saw the graves of our righteous Patriarchs in Hebron and the grave of Abner the son of Ner." Adler postulates that the visit must have occurred prior to Saladin's capture of Jerusalem in 1187.

Rabbi Moses Basola records visiting the tomb in 1522. He states, "Abner's grave is in the middle of Hebron; the Muslims built a mosque over it."[17] Another visitor in the 1500s states that "at the entrance to the market in Hebron, at the top of the hill against the wall, Abner ben Ner is buried, in a church, in a cave." This visit was recorded in Sefer Yihus ha-Tzaddiqim (Book of Genealogy of the Righteous), a collection of travelogues from 1561. Abraham Moshe Lunz reprinted the book in 1896.[18]

Menahem Mendel of Kamenitz, considered the first hotelier in the Land of Israel,[19] wrote about the Tomb of Abner is his 1839 book Korot Ha-Itim, which was translated into English as The Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel. He states, "Here I write of the graves of the righteous to which I paid my respects. Hebron – Described above is the character and order of behavior of those coming to pray at the Cave of ha-Machpelah. I went there, between the stores, over the grave of Avner ben Ner and was required to pay a Yishmaeli – the grave was in his courtyard – to allow me to enter."[20]

The author and traveler J. J. Benjamin mentioned visiting the tomb in his book Eight Years in Asia and Africa (1859, Hanover). He states, "On leaving the Sepulchre of the Patriarchs, and proceeding on the road leading to the Jewish quarter, to the left of the courtyard, is seen a Turkish dwelling house, by the side of which is a small grotto, to which there is a descent of several steps. This is the tomb of Abner, captain of King Saul. It is held in much esteem by the Arabs, and the proprietor of it takes care that it is always kept in the best order. He requires from those who visit it a small gratuity."[21]

The British scholar Israel Abrahams wrote in his 1912 book The Book of Delight and Other Papers, "Hebron was the seat of David's rule over Judea. Abner was slain here by Joab, and was buried here – they still show Abner's tomb in the garden of a large house within the city. By the pool at Hebron were slain the murderers of Ishbosheth..."[22]

Over the years the tomb fell into disrepair and neglect. It was closed to the public in 1994. In 1996, a group of 12 Israeli women filed a petition with the Supreme Court requesting the government to reopen the Tomb of Abner.[23] More requests were made over the years[24] and eventually arrangements were made to have the site open to the general public[dubious – discuss] on ten days throughout the year corresponding to the ten days that the Isaac Hall of the Cave of the Patriarchs is open.[25] In early 2007 new mezuzot were affixed to the entrance of the site.[26]

In popular culture

[edit]- 1960, David and Goliath (film) – Abner is portrayed by Massimo Serato. In this version, Abner tries to murder David (Ivica Pajer) when he returns in triumph after killing Goliath. However, here Abner is slain by King Saul (Orson Welles).

- 1961, A Story of David (film) – Abner is portrayed by Welsh actor David Davies.

- 1976, The Story of David (television series) – Younger version of Abner is portrayed by Israeli actor Yehuda Efroni. Older version of Abner is portrayed by British actor Brian Blessed.

- 1985, King David (film) – Abner is portrayed by English actor John Castle. King David portrayed by Richard Gere.

- 1997, King David (musical) – written by Tim Rice and Alan Menken. Abner is portrayed by American actor Timothy Shew.

- 1997, David (television drama) – Abner is portrayed by Richard Ashcroft.

- 2009, Kings (television series) – Abner portrayed by Wes Studi as General Linus Abner. The series is set in a multi-ethnic Western culture similar to that in the present-day United States, but with characters drawn from the Bible.

- 2012, Rei Davi (Brazilian television series) – Abner is portrayed by Iran Malfitano.

- 2025, House of David – Abner is portrayed by Oded Fehr

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Chisholm (1911), [t]he object of the story of the encounter is to explain the name Helkath-hazzurim, the meaning of which is doubtful (Ency. Bib. col. 2006; Batten in Zeit. f. alt-test. Wissens. 1906, pp. 90 sqq.).

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ 1 Samuel 14:50, 20:25

- ^ "1 Samuel 14:50 Interlinear: and the name of the wife of Saul is Ahinoam, daughter of Ahimaaz; and the name of the head of his host is Abner son of Ner, uncle of Saul;". biblehub.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ 1 Samuel 14:50, 17:55, 26:5)

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abner". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 66.

- ^ 2 Samuel 2:12

- ^ 2 Samuel 2:18

- ^ cf. 2 Samuel 3:7

- ^ cf. 2 Samuel 16:21ff.

- ^ 2 Samuel 3:31–39; cf. 1 Kings 2:31ff.

- ^ 2 Samuel 3:31–32

- ^ "Shmuel II – Chapter 3". Chabad. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ 2 Samuel 4:5–12

- ^ 2 Samuel 5:1–5

- ^ Price & Ginzberg 1901, pp. 71–72.

- ^ The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela: Travels in the Middle Ages. New York: NightinGale Resources. 1 March 2004. ISBN 9780911389098.

- ^ Adler, Elkan Nathan, ed. (30 November 2011). Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages: 19 Firsthand Accounts. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486253978.

- ^ Avraham, David (31 December 1999). In Zion and Jerusalem: The Itinerary of Rabbi Moses Basola 1512–1523. Jerusalem: C G Gundation. ISBN 9789652229267.

- ^ Ochser, Schulim. "URI (ORI) BEN SIMEON". History and Anthropology in Jewish Studies. Penn Libraries. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "The first Holy Land hotelier". The Jerusalem Post. 29 March 2010. ISSN 0792-822X. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ Cook, David; Cohen, Sol (August 2011). ""Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel" by David G. Cook and Sol P. Cohen". Miscellaneous Papers (10). Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ "Eight years in Asia and Africa from 1846–1855 : Israel Joseph Benjamin : Free Download & Streaming". Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ Abrahams, Israel (5 January 2016). The Book of Delight and Other Papers. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781523233328.

- ^ "Google Groups". groups.google.com. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Articles by David Wilder: The Mystery of the Tomb of Avner ben Ner or Understanding Uzi's Whims". davidwilder.blogspot.co.il. 20 May 1997. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Machpela website". Archived from the original on 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Shturem". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016.

Cited sources

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Price, Ira Maurice; Ginzberg, Louis (1901). "Abner or Abiner ("My Father is Ner")". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 71–72.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Price, Ira Maurice; Ginzberg, Louis (1901). "Abner or Abiner ("My Father is Ner")". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 71–72.

External links

[edit]- Pictures of Avner ben Ner's Tomb in Hebron

- Tomb of Abner page on Hebron.com website.

- David, Abraham (ed.) (1999). In Zion and Jerusalem: The Itinerary of Rabbi Moses Basola (1521–1523) C. G. Foundation Jerusalem Project Publications of the Martin (Szusz) Department of Land of Israel Studies of Bar-Ilan University ISBN 9652229261. Reference is made to visiting the tomb of Abner. (p. 77).

- Photo of prayer at the Tomb of Abner from Imagekind Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- Photo of prayer at the Tomb of Abner from PicJew.