Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Adduct

View on WikipediaIn chemistry, an adduct (from Latin adductus 'drawn toward'; alternatively, a contraction of "addition product") is a product of a direct addition of two or more distinct molecules, resulting in a single reaction product containing all atoms of all components.[1] The resultant is considered a distinct molecular species. Examples include the addition of sodium bisulfite to an aldehyde to give a sulfonate. It can be considered as a single product resulting from the direct combination of different molecules which comprises all atoms of the reactant molecules.

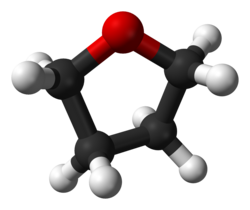

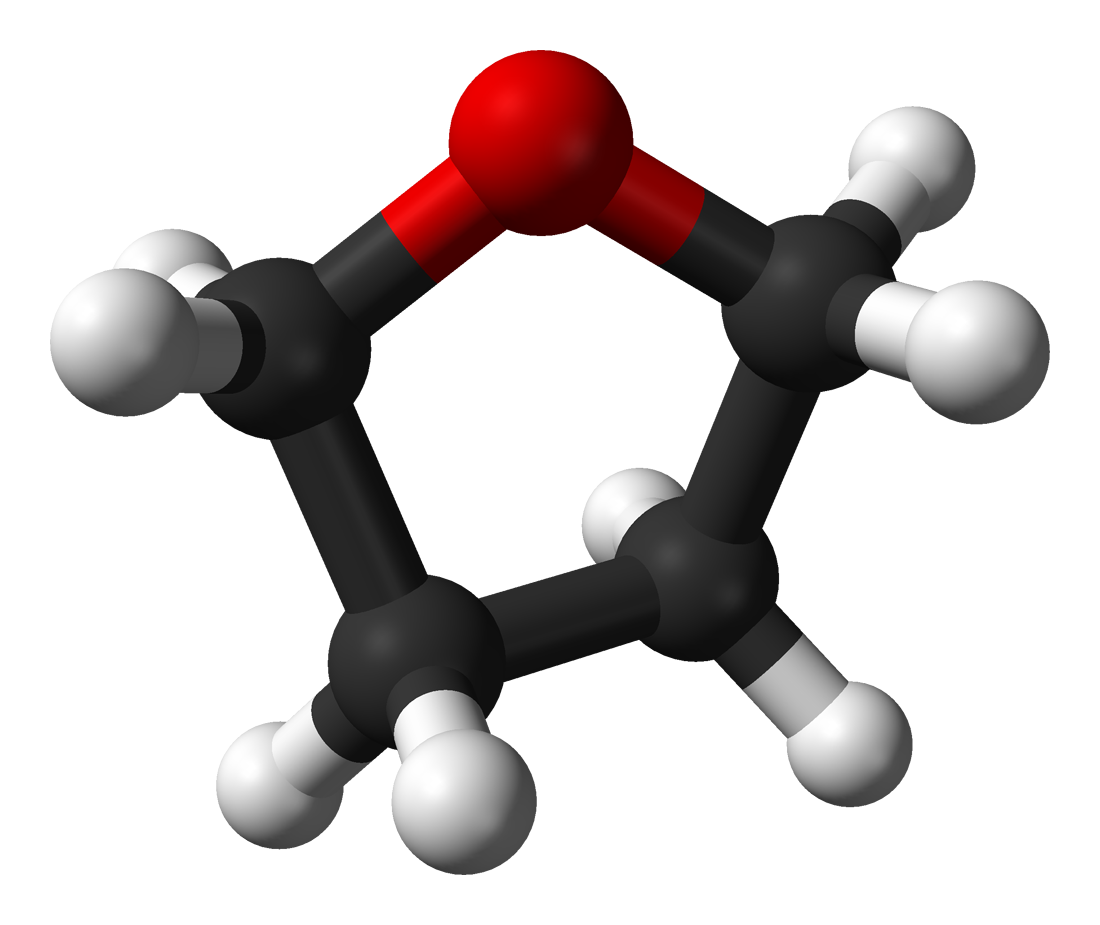

Adducts often form between Lewis acids and Lewis bases.[2] A good example is the formation of adducts between the Lewis acid borane and the oxygen atom in the Lewis bases, tetrahydrofuran (THF): BH3·O(CH2)4 or diethyl ether: BH3·O(CH3CH2)2. Many Lewis acids and Lewis bases reacting in the gas phase or in non-aqueous solvents to form adducts have been examined in the ECW model.[3] Trimethylborane, trimethyltin chloride and bis(hexafluoroacetylacetonato)copper(II) are examples of Lewis acids that form adducts which exhibit steric effects. For example: trimethyltin chloride, when reacting with diethyl ether, exhibits steric repulsion between the methyl groups on the tin and the ethyl groups on oxygen. But when the Lewis base is tetrahydrofuran, steric repulsion is reduced. The ECW model can provide a measure of these steric effects.

Compounds or mixtures that cannot form an adduct because of steric hindrance are called frustrated Lewis pairs.

Adducts are not necessarily molecular in nature. A good example from solid-state chemistry is the adducts of ethylene or carbon monoxide of CuAlCl4. The latter is a solid with an extended lattice structure. Upon formation of the adduct, a new extended phase is formed in which the gas molecules are incorporated (inserted) as ligands of the copper atoms within the structure. This reaction can also be considered a reaction between a base and a Lewis acid where the copper atom plays the electron-receiving role and the pi electrons of the gas molecule play the electron-donating role.[4]

Adduct ions

[edit]An adduct ion is formed from a precursor ion and contains all of the constituent atoms of that ion as well as additional atoms or molecules.[5] Adduct ions are often formed in a mass spectrometer ion source.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "adduct". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00138

- ^ Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2008). "Acids, bases and ions in aqueous solution". Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ Vogel G. C.; Drago, R. S. (1996). "The ECW Model". Journal of Chemical Education. 73 (8): 701–707. Bibcode:1996JChEd..73..701V. doi:10.1021/ed073p701.

- ^ Capracotta, M. D.; Sullivan, R. M.; Martin, J. D. (2006). "Sorptive Reconstruction of CuMCl4 (M = Al and Ga) upon Small-Molecule Binding and the Competitive Binding of CO and Ethylene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (41): 13463–13473. Bibcode:2006JAChS.12813463C. doi:10.1021/ja063172q. PMID 17031959.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "adduct ion (in mass spectrometry)". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00139

Adduct

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Definition

An adduct is a chemical species formed by the direct combination of two separate molecular entities, resulting in a single product that incorporates all atoms from the reactants without the loss of any small molecules or atoms.[1] This process typically involves the formation of a new bond, often dative or coordinate, between a Lewis acid and a Lewis base, yielding a stable yet potentially reversible association.[1] The term "adduct" originated in the late 19th century within the field of coordination chemistry, where it described addition products of metal salts with ligands such as ammonia. Early examples include the adducts of platinum chloride with ammonia, PtCl₄·nNH₃ (where n = 2–6), which were studied prior to and during Alfred Werner's foundational work on coordination compounds beginning around 1893. Werner's research, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1913, formalized the understanding of these adducts as complexes with defined coordination numbers and geometries.[8] A representative example is the 1:1 addition of sodium bisulfite (NaHSO₃) to an aldehyde, such as benzaldehyde, producing a water-soluble sulfonate adduct that facilitates purification or isolation of the carbonyl compound.[9]Key Characteristics

Adducts exhibit a distinctive bonding nature centered on donor-acceptor interactions, most prominently through dative (coordinate covalent) bonds in Lewis acid-base systems, where the donor (Lewis base) provides both electrons to form the bond with the acceptor (Lewis acid).[10] These bonds differ from standard covalent bonds by their origin from a lone pair on the donor atom. This bonding involves a change in connectivity and may include weaker interactions like π-adducts or charge-transfer complexes in specialized contexts, but the core definition emphasizes chemical bonding over mere physical stabilization.[1][11] Structurally, adducts are frequently denoted using a dot (·) in their chemical formulas to signify the non-covalent or coordinate linkage between components, as seen in the prototypical example of borane-tetrahydrofuran, , where the oxygen lone pair coordinates to the boron center.[12] This notation highlights the modular assembly without implying a traditional single molecule. Adducts may manifest as discrete, isolable molecular entities in solution or gas phase, or as extended lattice networks in crystalline solids, where multiple interactions propagate the structure. Stoichiometry in adducts is predominantly 1:1, corresponding to a single donor-acceptor pair that satisfies the electron demands of the Lewis acid.[13] However, higher-order stoichiometries, such as 1:2 (one acceptor to two donors), arise when the acceptor's electron deficiency requires multiple donations for stabilization, as in the diamminesilver(I) ion .[14] The prevalence of these ratios is governed by the acceptor's capacity to accommodate additional ligands without steric hindrance or electronic saturation. Thermodynamically, adduct formation is typically exothermic, with negative enthalpy changes arising from the energetic favorability of the donor-acceptor bond, though entropy effects from loss of translational freedom can modulate overall stability.[15] These reactions are reversible, establishing equilibria whose constants vary significantly with solvent polarity and coordinating ability, as solvation competes with or enhances the intramolecular interaction.[16]Types of Adducts

Lewis Acid-Base Adducts

Lewis acid-base adducts form through the donation of an electron pair from a Lewis base to an electron-deficient Lewis acid, resulting in a coordinate covalent bond between the donor and acceptor atoms. This interaction exemplifies the Lewis definition of acids and bases, where the acid accepts the pair and the base provides it, without requiring proton transfer.[17] The general formation can be represented as: A classic example is the reaction of trimethylborane with ammonia: X-ray crystallographic analysis reveals a B-N bond length of approximately 1.6 Å in this adduct, indicative of the dative bonding character. Prominent examples include the borane-tetrahydrofuran adduct (BH₃·THF), in which the oxygen atom of THF donates a lone pair to the empty p-orbital on boron, stabilizing the otherwise unstable BH₃ monomer.[17] Similarly, trimethylaluminum forms adducts with amines (Me₃Al·NR₃), where the nitrogen lone pair coordinates to the aluminum center, enhancing the utility of these species as reagents in synthetic chemistry. These main-group element adducts highlight the prevalence of such interactions in organic and inorganic systems, often serving as protected forms of reactive Lewis acids. Steric hindrance from bulky substituents can prevent the close approach of the acid and base, inhibiting classical adduct formation and instead yielding frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs). In FLPs, the unquenched Lewis acidity and basicity enable cooperative activation of small molecules like H₂. For instance, mesitylborane (Mes₃B, where Mes is 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl) paired with bulky phosphines exemplifies this phenomenon, as the steric bulk around boron and phosphorus precludes dative bond formation. This concept, introduced in seminal work on metal-free hydrogen activation, has expanded the scope of Lewis acid-base chemistry beyond traditional adducts.Coordination Adducts

Coordination adducts, also known as coordination complexes, are chemical species in which ligands donate electron pairs to a central transition metal ion through dative bonds, frequently resulting in coordination numbers of six or eight for the central metal ion.[18] These adducts are a type of Lewis acid-base adduct where the central metal ion acts as the Lewis acid and ligands serve as bases, forming stable structures central to coordination chemistry.[2] The foundational understanding of coordination adducts emerged from the work of Alfred Werner, who in 1913 received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for elucidating the structures of such compounds, proposing octahedral geometries for many metal centers surrounded by six ligands.[19] Werner's studies on cobaltammine complexes, such as hexaamminecobalt(III) ion , exemplified these adducts as products of Co³⁺ ions coordinating with six NH₃ ligands via dative bonds, demonstrating fixed coordination numbers and isomerism that challenged prevailing valence theories.[20] A classic organometallic example is Zeise's salt, , where ethylene acts as a ligand bound to Pt(II) in a square-planar arrangement, illustrating how unsaturated hydrocarbons can form adducts with transition metals.[21] In these metal-ligand adducts, bonding arises primarily from σ-donation of ligand lone pairs or π-electrons into empty metal d-orbitals, complemented by π-backbonding where filled metal d-orbitals donate electrons to the ligand's empty π* antibonding orbitals, strengthening the interaction.[22] For ethylene in Zeise's salt, the ligand exhibits η²-hapticity, coordinating through both carbon atoms in a side-on manner to facilitate this synergistic donation and backbonding.[23]Adduct Ions

Adduct ions are positively or negatively charged species resulting from the attachment of a neutral molecule, atom, or ion to a precursor ion, thereby incorporating all constituent atoms of the precursor along with the additional components from the adducting species. These ions commonly form through interactions with solvents, ligands, or ambient species during ionization processes. In mass spectrometry, adduct ions are prevalent in soft ionization techniques such as electrospray ionization (ESI), where they preserve molecular integrity with minimal fragmentation.[24] For instance, in positive-ion ESI mode, common adducts include the protonated form [M + H]⁺ and the sodiated form [M + Na]⁺, arising from trace protons or sodium ions in the sample or solvent.[24] These adducts play a crucial role in ESI by facilitating the transfer of analytes from solution to the gas phase as intact pseudomolecular ions.[25] Similar adduct formation occurs in matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry, another soft ionization method suited for large biomolecules.[26] Protonated dimers, such as [2M + H]⁺, can appear due to proton transfer reactions involving matrix molecules, providing insights into ionization pathways.[26] In negative-ion mode, chloride adducts like [M + Cl]⁻ are observed, particularly with matrices that promote anion attachment, such as 3-hydroxypicolinic acid for peptides like insulin.[26] The presence of adduct ions influences analytical outcomes by shifting the observed mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios, often requiring deconvolution algorithms or adduct identification to accurately determine the neutral molecular weight.[24] For example, distinguishing [M + H]⁺ from [M + Na]⁺ based on consistent mass differences (e.g., 22 Da) confirms the analyte identity and corrects for adduct contributions.[24] Uncontrolled adducts from contaminants can complicate spectra, but their recognition enhances structural elucidation in complex mixtures.[24]Formation Mechanisms

Reaction Pathways

The formation of adducts generally proceeds through a nucleophilic attack by the Lewis base donor on the electrophilic Lewis acid acceptor, involving the donation of an electron pair to form a dative bond. This process is typically associative, proceeding via a transition state where the donor and acceptor partially bond before full adduct formation. For Lewis acid-base adducts, the pathway involves direct electron pair donation from the base to an empty orbital on the acid, often without dissociation of existing bonds on the acid. In contrast, coordination adducts form through pathways such as ligand substitution, where an incoming ligand displaces an existing one via associative or dissociative mechanisms, or oxidative addition, in which a reagent adds across the metal center, increasing both the coordination number and oxidation state by two.[27] Kinetic studies of adduct formation often reveal second-order rate laws, indicative of a bimolecular process. Energy diagrams for adduct formation typically illustrate an activation barrier corresponding to the transition state, followed by an exothermic step with enthalpy change , reflecting the dative bond strength. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations predict bond dissociation energies for BH₃-amine adducts in the range of 27–33 kcal/mol in the gas phase, providing insight into the thermodynamic driving force and barrier heights for these pathways.[28][29]Factors Influencing Formation

The formation of adducts is modulated by several key factors, including steric hindrance, electronic properties of the reacting species, solvent environment, and thermodynamic conditions such as temperature and pressure. These variables influence the equilibrium constant for adduct formation, often described by the association reaction between a Lewis acid (LA) and Lewis base (LB) to yield the adduct (LA·LB). Understanding these factors is essential for predicting and controlling adduct reactivity in chemical systems.[16] Steric factors play a critical role in adduct formation by introducing strain that can reduce association constants, particularly when bulky substituents prevent optimal overlap of donor and acceptor orbitals. For instance, in frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs), large groups such as tert-butyl substituents on phosphines (e.g., P(tBu)₃) and perfluorophenyl groups on boranes (e.g., B(C₆F₅)₃) sterically inhibit classical adduct formation, leading to weaker or nonexistent dative bonds while enabling alternative reactivity pathways like small molecule activation. This steric encumbrance increases B–N or B–P bond lengths in potential adducts, as observed in a series of ortho-substituted aminoboranes where electron-withdrawing and bulky aryl groups on boron significantly lengthen these distances compared to less hindered analogs.[30][31] Electronic effects determine the intrinsic affinity of Lewis acids and bases for adduct formation, with stronger acceptors and more basic donors favoring higher association constants. The strength of a Lewis acid like boron trifluoride (BF₃) arises from its empty p-orbital on boron, which is highly electron-deficient due to the electronegative fluorine atoms minimizing back-donation and enhancing electrophilicity; in contrast, trimethylborane (BMe₃) exhibits weaker acidity because the electron-donating methyl groups increase electron density on boron via inductive and hyperconjugative effects, reducing its ability to accept electron pairs from hard bases. Donor basicity, often quantified by the pKₐ of the conjugate acid for amine or phosphine bases, correlates with the availability of the lone pair for donation, where higher pKₐ values (indicating stronger bases) promote more stable adducts, as established in comprehensive Lewis basicity scales that account for electronic perturbations in adduct equilibria.[32] Solvent effects significantly alter adduct formation by influencing solvation energies and competing interactions with the acid or base. Polar aprotic solvents, such as tetrahydrofuran (THF), stabilize ionic or polar transition states without strongly solvating the lone pair of the Lewis base, thereby favoring adduct formation; for example, the BH₃·THF adduct is readily formed and stable in THF due to minimal disruption of the dative bond. In contrast, protic solvents like water or alcohols disrupt adducts through hydrogen bonding to the base, which competes with the acid-base interaction and lowers association constants, as demonstrated in fluorescent Lewis adduct studies where donating solvents reduce binding affinities by forming solvates that limit free acid availability.[16][33] Temperature and pressure exert thermodynamic control over adduct equilibria via Le Chatelier's principle, as most adduct formations are exothermic and involve a decrease in the number of particles. Lower temperatures shift the equilibrium toward adduct formation by favoring the enthalpy-driven association, with studies on gas-phase reactions like N(CH₃)₃ + BF₃ showing negative ΔH values (typically -60 to -100 kJ/mol) that make the equilibrium constant increase as temperature decreases. In the gas phase, higher pressure promotes association by reducing the volume (fewer moles on the product side).[34]Stability and Properties

Stability

The thermodynamic stability of adducts is primarily governed by the bond dissociation energy (BDE) of the coordinate covalent bond and the equilibrium constant for adduct formation. For Lewis acid-base adducts, such as B-N bonds in amine borane compounds, BDEs typically range from 12 to 32 kcal/mol at 298 K, with the simple adduct BH₃·NH₃ exhibiting a BDE of 27.1 kcal/mol.[35] The equilibrium constant quantifies the position of the dissociation equilibrium; for triarylborane adducts with nitrogen bases in dichloromethane at 20 °C, values span to M⁻¹, reflecting varying stabilities influenced by steric and electronic factors.[36] Lower BDEs, often below 15 kcal/mol, lead to borderline stability at room temperature due to entropic contributions from dissociation (TΔS ≈ 10–15 kcal/mol). Kinetic stability arises from activation energies for dissociation, which determine the rate of bond breaking. In coordination adducts, bidentate or chelating ligands exhibit higher activation energies for dissociation compared to monodentate analogs, as the chelate effect requires simultaneous or stepwise breaking of multiple bonds, slowing the overall process.[37] This kinetic barrier enhances persistence under conditions where thermodynamic dissociation might otherwise occur readily. Factors influencing adduct stability include pH in aqueous environments and thermal conditions. For aqueous adducts like the glyoxylic acid–S(IV) complex, stability decreases with increasing pH (0.7–2.9 range), as deprotonation shifts speciation toward less favorable forms, reducing formation constants from M⁻¹ at lower pH to M⁻¹ at higher pH.[38] Thermal decomposition often proceeds via retro-addition pathways, where heating reverses the Lewis acid-base association; for example, amine borane adducts lose BH₃ upon heating, driven by endothermic dissociation when BDEs are modest.[35] Stability parameters are measured using techniques like calorimetry for enthalpic changes (ΔH) and stopped-flow kinetics for dissociation rates. Isothermal titration calorimetry determines ΔH for adduct formation, as in the donor number scale based on SbCl₅–base enthalpies in sulfolane, providing quantitative acidity/basicity insights. Stopped-flow methods capture rapid dissociation kinetics on millisecond timescales, enabling calculation of activation energies from rate constants for ligand exchange or bond breaking in coordination adducts.[39]Spectroscopic Properties

Spectroscopic techniques play a crucial role in identifying and characterizing adducts by revealing changes in molecular environments upon Lewis acid-base coordination. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is particularly valuable for detecting shifts in the signals of donor atoms or protons in the ligand. In Lewis acid-base adducts, the protons on the donor ligand often exhibit distinct chemical shift changes due to the electronic perturbation from coordination. For instance, in adducts involving nitrogen donors like N,N-dimethylformamide, the proton resonance signals shift noticeably compared to the free ligand, reflecting the dative bond formation.[40] Similarly, in coordinated ammonia or amine ligands, such as in boron-nitrogen adducts, the donor NH protons can shift upfield, as observed in certain porphyrin-based systems where NH signals move from -2.7 ppm in the free base to -3.2 ppm upon adduct formation with BF₃.[41] For boron-containing adducts, ¹¹B NMR is diagnostic, often showing quadrupolar broadening due to the nuclear spin (I = 3/2) of ¹¹B and relaxation effects from the asymmetric environment in the adduct. This broadening is evident in boron-nitrogen adducts, where line widths increase owing to quadrupole-induced relaxation and chemical exchange processes.[42] Infrared (IR) spectroscopy provides direct evidence of adduct formation through the appearance or modification of vibrational modes associated with the metal-ligand (M-L) bond. New absorption bands corresponding to M-L stretching vibrations emerge, while modes of the free ligand may diminish or shift. In coordination adducts, these stretches typically appear in characteristic regions; for example, B-O stretches in boron-oxygen adducts are observed around 1310–1350 cm⁻¹, indicating the strength of the dative interaction.[43] B-N stretches in amine-borane adducts often fall in the 700–900 cm⁻¹ range, with additional confirmation from the alteration of ligand-specific modes.[44] A representative example is the BH₃·THF adduct, where the B-H stretching vibrations, normally around 2400 cm⁻¹ in free borane, split and shift to lower frequencies (e.g., 2375, 2340, and 2280 cm⁻¹) due to coordination with the THF oxygen, as the asymmetric environment weakens the bonds.[45][46] The disappearance of free THF C-O stretches around 1100 cm⁻¹ further supports adduct formation. In broader coordination compounds, M-L stretches for transition metals appear in the 200–600 cm⁻¹ region, though specific assignments depend on the metal and ligand.[47] Other spectroscopic methods complement NMR and IR for adduct characterization. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy detects charge-transfer (CT) bands arising from electron density transfer between the metal and ligand in coordination adducts, often appearing as intense absorptions in the visible region (e.g., 300–600 nm) that are absent in the free components. These CT bands, such as ligand-to-metal or metal-to-ligand transitions, provide insight into the electronic structure and are more intense than d-d transitions.[48] Mass spectrometry, particularly electrospray ionization (ESI-MS), confirms adduct ions by observing the molecular ion peak corresponding to the combined mass of the acid and base components, often with alkali metal adducts like [M+Na]⁺ for added specificity in solution-phase studies. This technique is especially useful for adduct ions, where the intact adduct peak distinguishes them from dissociated species.[49]Applications

In Organic Synthesis

Adducts play a crucial role as reagents in organic synthesis, particularly in facilitating selective additions to unsaturated systems. Borane adducts, such as BH₃·SMe₂, are widely employed in hydroboration reactions, where they add across carbon-carbon double bonds of alkenes in an anti-Markovnikov, syn fashion, enabling the synthesis of organoboranes that can be oxidized to alcohols.[50] This approach, pioneered by Herbert C. Brown, provides a stereospecific route to primary alcohols from terminal alkenes, contrasting with acid-catalyzed hydration methods.[51] Similarly, Grignard reagents (RMgX) add nucleophilically to carbonyl compounds like aldehydes and ketones, forming magnesium alkoxides that, upon hydrolysis, yield secondary or tertiary alcohols, thereby extending carbon chains in a controlled manner.[52] In synthetic strategies, adducts serve as protecting groups to mask reactive functionalities during multi-step sequences. Amine-borane adducts, for instance, protect primary and secondary amines by forming stable B-N bonds, preventing interference in reductions of other groups such as nitro compounds to anilines or carboxylic acids to alcohols.[53] This protection is particularly valuable in selective hydroboration or hydrogenation, where free amines might coordinate to catalysts or reagents, disrupting reactivity. Additionally, transient adducts are integral to catalytic processes like olefin metathesis, where ruthenium-carbene complexes form short-lived π-adducts with alkenes, facilitating carbene exchange and C-C bond redistribution without permanent incorporation of the metal.[54] These intermediates enable efficient synthesis of complex alkenes from simpler precursors, as exemplified in Grubbs-type catalysis. The advantages of using adducts often stem from improved solubility and safer handling of inherently reactive species. For example, the trimethylamine adduct of aluminum hydride (AlH₃·NMe₃) enhances the solubility of polymeric AlH₃ in organic solvents, allowing mild reductions of esters, epoxides, and nitriles to alcohols or amines under conditions where LiAlH₄ might over-reduce.[55] This adduct's stability facilitates precise control over reaction stoichiometry and minimizes side reactions. In contexts resembling Diels-Alder reactivity, non-cycloaddition adducts form when Lewis acids coordinate to the carbonyl oxygen of dienophiles, polarizing the π-bond for enhanced electrophilicity without forming a cyclic product; this activation accelerates subsequent cycloadditions but the initial adduct itself is a simple donor-acceptor complex, distinct from the pericyclic [4+2] pathway.[56]In Analytical Chemistry

In analytical chemistry, adducts play a crucial role in enhancing the sensitivity and specificity of identification and quantification techniques, particularly in mass spectrometry and chromatography. In mass spectrometry, adduct ions are intentionally formed to improve ionization efficiency, especially for analytes that ionize poorly in standard modes. For instance, in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), the addition of formate to the mobile phase promotes the formation of [M+formate]- adducts in negative electrospray ionization (ESI) mode, facilitating the analysis of neutral or acidic compounds by providing a stable, detectable ion species.[57][58] This approach is particularly useful for biomolecules like high explosives or pharmaceuticals, where formate attachment yields reproducible fragmentation patterns for structural confirmation.[57] Adducts also enable isotope labeling strategies in mass spectrometry for accurate quantification. Stable isotope-labeled internal standards, often incorporated via adduct formation, allow for precise measurement of analytes by distinguishing labeled from unlabeled species in isotope dilution methods, such as in the analysis of DNA adducts or metabolites.[59] This technique minimizes matrix effects and improves detection limits, as the isotopic shift in mass-to-charge ratio provides a direct reference for calibration without altering the chemical behavior of the analyte.[60] In chromatography, adduct formation through derivatization is essential for preparing non-volatile or polar compounds for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Silylation, a common method, converts functional groups like hydroxyl in alcohols into trimethylsilyl (TMS) adducts, increasing volatility and thermal stability to enable efficient separation and detection.[61] For example, reagents such as N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) react rapidly with alcohols to form TMS ethers, which exhibit characteristic fragmentation in MS for identification, as seen in steroid or carbohydrate analyses.[62] This derivatization enhances peak shape and sensitivity, avoiding adsorption issues on GC columns.[63] Beyond spectrometric methods, adducts are utilized in complexometric titrations for endpoint detection in metal ion quantification. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) forms stable 1:1 chelate complexes (adducts) with divalent metal ions like calcium or magnesium, displacing indicator-metal complexes to produce a sharp color change at the equivalence point.[64] Indicators such as Eriochrome Black T bind weakly to metals but release upon EDTA adduct formation, enabling visual or photometric detection with high precision in water hardness or pharmaceutical assays.[65] A key challenge in adduct-based analyses, particularly in ESI-MS, is the formation of unwanted adducts from endogenous ions like sodium or chloride, which can suppress target signals and complicate spectra. Additives such as acetic acid in the mobile phase are employed to lower pH and favor protonation over metal adduction, thereby enhancing the abundance of desired [M+H]+ or [M-H]- ions while minimizing interferences.[66] This strategy, often combined with chelating agents, improves quantification accuracy in complex biological matrices.[67]In Materials Science

In materials science, adducts play a pivotal role in crystal engineering through the formation of host-guest inclusion compounds, where host molecules create structured voids that encapsulate guest species via non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding. A classic example is the urea-channel adduct, in which urea molecules self-assemble into a hexagonal array of parallel channels approximately 0.5 nm in diameter through extensive hydrogen bonding, selectively including linear hydrocarbons like n-alkanes while excluding branched isomers.[68] This templated crystal growth mechanism allows for precise control over guest ordering and superstructure, enabling applications in hydrocarbon separation by exploiting differences in molecular shape and size.[68] Coordination adducts are integral to the design of polymers and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), serving as linking nodes that enhance structural integrity and functionality. In Zn-based MOFs, urea-functionalized ligands, such as those incorporating carboxylate or pyridyl groups, form coordination bonds with Zn(II) centers to yield porous 3D networks with tunable pore apertures.[69] These adducts promote strong interactions with guest gases via hydrogen bonding from the urea NH groups and the Lewis basicity of the carbonyl, resulting in enhanced uptake capacities—for instance, selective adsorption of CO₂ over CH₄ due to quadrupole interactions and pore confinement effects.[69] Such materials exemplify how coordination adducts enable high surface areas exceeding 1000 m²/g, supporting gas storage applications in energy-efficient systems.[69] Supramolecular assemblies leverage hydrogen-bonded adducts to construct mechanically interlocked structures like rotaxanes and catenanes, where macrocycles encircle linear threads through directional non-covalent bonds. In barbiturate-based [70]-rotaxanes, the barbiturate motif on the thread forms multiple hydrogen bonds with a macrocycle bearing complementary 2,6-diamidopyridine units, stabilizing the interlocked architecture during synthesis via copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition stoppering.[71] These adducts facilitate dynamic motion along the thread, mimicking molecular machines, and contribute to the formation of higher-order assemblies with potential in responsive materials.[71] Adducts also impart exploitable properties such as tunable porosity and electrical conductivity in solid-state materials. Charge-transfer adducts like tetrathiafulvalene-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TTF-TCNQ) form segregated stacks of donor and acceptor molecules, enabling partial electron transfer (approximately 0.59 electrons per unit) that generates metallic conductivity up to 1000 S/cm at room temperature along the stack direction.[72] This quasi-one-dimensional conduction arises from band overlap in the charge-transfer complex, with tunability achieved through external pressure or substitution to modulate charge density waves and transition to superconducting states in related systems.[72] Such properties position TTF-TCNQ as a benchmark for organic electronic materials in conductors and semiconductors.[72]References

- The bonded acid-base species is called an adduct (short for addition product), a coordination compound, or a complex.