Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cabin pressurization

View on Wikipedia

Cabin pressurization is a process in which conditioned air is pumped into the cabin of an aircraft or spacecraft in order to create a safe and comfortable environment for humans flying at high altitudes. For aircraft, this air is usually bled off from the gas turbine engines at the compressor stage, and for spacecraft, it is carried in high-pressure, often cryogenic, tanks. The air is cooled, humidified, and mixed with recirculated air by one or more environmental control systems before it is distributed to the cabin.[1]

The first experimental pressurization systems saw use during the 1920s and 1930s. In the 1940s, the first commercial aircraft with a pressurized cabin entered service.[2] The practice would become widespread a decade later, particularly with the introduction of the British de Havilland Comet jetliner in 1949. However, two catastrophic failures in 1954 temporarily grounded the Comet worldwide.[3] These failures were investigated and found to be caused by a combination of progressive metal fatigue and aircraft skin stresses caused from pressurization. Improved testing involved multiple full-scale pressurization cycle tests of the entire fuselage in a water tank,[3] and the key engineering principles learned were applied to the design of subsequent jet airliners.

Certain aircraft have unusual pressurization needs. For example, the supersonic airliner Concorde had a particularly high pressure differential due to flying at unusually high altitude: up to 60,000 ft (18,288 m) while maintaining a cabin altitude of 6,000 ft (1,829 m). This increased airframe weight and saw the use of smaller cabin windows intended to slow the decompression rate if a depressurization event occurred.

The Aloha Airlines Flight 243 incident in 1988, involving a Boeing 737-200 that suffered catastrophic cabin failure mid-flight, was primarily caused by the aircraft's continued operation despite having accumulated more than twice the number of flight cycles that the airframe was designed to endure.[4]

For increased passenger comfort, several modern airliners, such as the Boeing 787 Dreamliner and the Airbus A350 XWB, feature reduced operating cabin altitudes as well as greater humidity levels; the use of composite airframes has aided the adoption of such comfort-maximizing practices.

Need for cabin pressurization

[edit]

Pressurization becomes increasingly necessary at altitudes above 10,000 ft (3,048 m) above sea level to protect crew and passengers from the risk of a number of physiological problems caused by the low outside air pressure above that altitude. For private aircraft operating in the US, crew members are required to use oxygen masks if the cabin altitude (a representation of the air pressure, see below) stays above 12,500 ft (3,810 m) for more than 30 minutes, or if the cabin altitude reaches 14,000 ft (4,267 m) at any time. At altitudes above 15,000 ft (4,572 m), passengers are required to be provided oxygen masks as well. On commercial aircraft, the cabin altitude must be maintained at 8,000 ft (2,438 m) or less. Pressurization of the cargo hold is also required to prevent damage to pressure-sensitive goods that might leak, expand, burst or be crushed on re-pressurization.

The principal physiological problems are listed below.

- Hypoxia

- The lower partial pressure of oxygen at high altitude reduces the alveolar oxygen tension in the lungs and subsequently in the brain, leading to sluggish thinking, dimmed vision, loss of consciousness, and ultimately death. In some individuals, particularly those with heart or lung disease, symptoms may begin as low as 5,000 ft (1,524 m), although most passengers can tolerate altitudes of 8,000 ft (2,438 m) without ill effect. At this altitude, there is about 25% less oxygen than there is at sea level.[5]

- Hypoxia may be addressed by the administration of supplemental oxygen, either through an oxygen mask or through a nasal cannula. Without pressurization, sufficient oxygen can be delivered up to an altitude of about 40,000 ft (12,192 m). This is because a person who is used to living at sea level needs about 0.20 bar (20 kPa; 2.9 psi) partial oxygen pressure to function normally and that pressure can be maintained up to about 40,000 ft (12,192 m) by increasing the mole fraction of oxygen in the air that is being breathed. At 40,000 ft (12,192 m), the ambient air pressure falls to about 0.2 bar, at which maintaining a minimum partial pressure of oxygen of 0.2 bar requires breathing 100% oxygen using an oxygen mask.

- Emergency oxygen supply masks in the passenger compartment of airliners do not need to be pressure-demand masks because most flights stay below 40,000 ft (12,192 m). Above that altitude the partial pressure of oxygen will fall below 0.2 bar even at 100% oxygen and some degree of cabin pressurization or rapid descent will be essential to avoid the risk of hypoxia.

- Altitude sickness

- Hyperventilation, the body's most common response to hypoxia, does help to partially restore the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood, but it also causes carbon dioxide (CO2) to out-gas, raising the blood pH and inducing alkalosis. Passengers may experience fatigue, nausea, headaches, sleeplessness, and (on extended flights) even pulmonary edema. These are the same symptoms that mountain climbers experience, but the limited duration of powered flight makes the development of pulmonary oedema unlikely. Altitude sickness may be controlled by a full pressure suit with helmet and faceplate, which completely envelops the body in a pressurized environment; however, this is impractical for commercial passengers.

- Decompression sickness

- The low partial pressure of gases, principally nitrogen (N2) but including all other gases, may cause dissolved gases in the bloodstream to precipitate out, resulting in gas embolism, or bubbles in the bloodstream. The mechanism is the same as that of compressed-air divers on ascent from depth. Symptoms may include the early symptoms of "the bends"—tiredness, forgetfulness, headache, stroke, thrombosis, and subcutaneous itching—but rarely the full symptoms thereof. Decompression sickness may also be controlled by a full-pressure suit as for altitude sickness.

- Barotrauma

- As the aircraft climbs or descends, passengers may experience discomfort or acute pain as gases trapped within their bodies expand or contract. The most common problems occur with air trapped in the middle ear (aerotitis) or paranasal sinuses by a blocked Eustachian tube or sinuses. Pain may also be experienced in the gastrointestinal tract or even the teeth (barodontalgia). Usually these are not severe enough to cause actual trauma but can result in soreness in the ear that persists after the flight[6] and can exacerbate or precipitate pre-existing medical conditions, such as pneumothorax.

Cabin altitude

[edit]

The pressure inside the cabin is technically referred to as the equivalent effective cabin altitude or more commonly as the cabin altitude. This is defined as the equivalent altitude above mean sea level having the same atmospheric pressure according to a standard atmospheric model such as the International Standard Atmosphere. Thus a cabin altitude of zero would have the pressure found at mean sea level, which is taken to be 101.325 kPa (14.696 psi; 29.921 inHg).[7]

Aircraft

[edit]In airliners, cabin altitude during flight is kept above sea level in order to reduce stress on the pressurized part of the fuselage; this stress is proportional to the difference in pressure inside and outside the cabin. In a typical commercial passenger flight, the cabin altitude is programmed to rise gradually from the altitude of the airport of origin to a regulatory maximum of 8,000 ft (2,438 m). This cabin altitude is maintained while the aircraft is cruising at its maximum altitude and then reduced gradually during descent until the cabin pressure matches the ambient air pressure at the destination.[citation needed]

Keeping the cabin altitude below 8,000 ft (2,438 m) generally prevents significant hypoxia, altitude sickness, decompression sickness, and barotrauma.[9] Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations in the U.S. mandate that under normal operating conditions, the cabin altitude may not exceed this limit at the maximum operating altitude of the aircraft.[10] This mandatory maximum cabin altitude does not eliminate all physiological problems; passengers with conditions such as pneumothorax are advised not to fly until fully healed, and people suffering from a cold or other infection may still experience pain in the ears and sinuses.[citation needed] The rate of change of cabin altitude strongly affects comfort as humans are sensitive to pressure changes in the inner ear and sinuses and this has to be managed carefully. Scuba divers flying within the "no fly" period after a dive are at risk of decompression sickness because the accumulated nitrogen in their bodies can form bubbles when exposed to reduced cabin pressure.

The cabin altitude of the Boeing 767 is typically about 7,000 ft (2,134 m) when cruising at 37,000 ft (11,278 m).[11] This is typical for older jet airliners. A design goal for many, but not all, newer aircraft is to provide a lower cabin altitude than older designs. This can be beneficial for passenger comfort.[12] For example, the Bombardier Global Express business jet can provide a cabin altitude of 4,500 ft (1,372 m) when cruising at 41,000 ft (12,497 m).[13][14][15] The Emivest SJ30 business jet can provide a sea-level cabin altitude when cruising at 41,000 ft (12,497 m).[16][17][unreliable source?] One study of eight flights in Airbus A380 aircraft found a median cabin pressure altitude of 6,128 ft (1,868 m), and 65 flights in Boeing 747-400 aircraft found a median cabin pressure altitude of 5,159 ft (1,572 m).[18]

Before 1996, approximately 6,000 large commercial transport airplanes were assigned a type certificate to fly up to 45,000 ft (13,716 m) without having to meet high-altitude special conditions.[19] In 1996, the FAA adopted Amendment 25–87, which imposed additional high-altitude cabin pressure specifications for new-type aircraft designs. Aircraft certified to operate above 25,000 ft (7,620 m) "must be designed so that occupants will not be exposed to cabin pressure altitudes in excess of 15,000 ft (4,572 m) after any probable failure condition in the pressurization system".[20] In the event of a decompression that results from "any failure condition not shown to be extremely improbable", the plane must be designed such that occupants will not be exposed to a cabin altitude exceeding 25,000 ft (7,620 m) for more than 2 minutes, nor to an altitude exceeding 40,000 ft (12,192 m) at any time.[20] In practice, that new Federal Aviation Regulations amendment imposes an operational ceiling of 40,000 ft (12,000 m) on the majority of newly designed commercial aircraft.[21][22] Aircraft manufacturers can apply for a relaxation of this rule if the circumstances warrant it. In 2004, Airbus acquired an FAA exemption to allow the cabin altitude of the A380 to reach 43,000 ft (13,106 m) in the event of a decompression incident and to exceed 40,000 ft (12,192 m) for one minute. This allows the A380 to operate at a higher altitude than other newly designed civilian aircraft.[21]

Spacecraft

[edit]Russian engineers used an air-like nitrogen/oxygen mixture, kept at a cabin altitude near zero at all times, in their 1961 Vostok, 1964 Voskhod, and 1967 to present Soyuz spacecraft.[23] This requires a heavier space vehicle design, because the spacecraft cabin structure must withstand the stress of 14.7 pounds per square inch (1 atm, 1.01 bar) against the vacuum of space, and also because an inert nitrogen mass must be carried. Care must also be taken to avoid decompression sickness when cosmonauts perform extravehicular activity, as current soft space suits are pressurized with pure oxygen at relatively low pressure in order to provide reasonable flexibility.[24]

By contrast, the United States used a pure oxygen atmosphere for its 1961 Mercury, 1965 Gemini, and 1967 Apollo spacecraft, mainly in order to avoid decompression sickness.[25][26] Mercury used a cabin altitude of 24,800 ft (7,600 m) (5.5 psi (0.38 bar));[27] Gemini used an altitude of 25,700 ft (7,800 m) (5.3 psi (0.37 bar));[28] and Apollo used 27,000 ft (8,200 m) (5.0 psi (0.34 bar))[29] in space. This allowed for a lighter space vehicle design. This is possible because at 100% oxygen, enough oxygen gets to the bloodstream to allow astronauts to operate normally. Before launch, the pressure was kept at slightly higher than sea level at a constant 5.3 psi (0.37 bar) above ambient for Gemini, and 2 psi (0.14 bar) above sea level at launch for Apollo), and transitioned to the space cabin altitude during ascent. However, the high pressure pure oxygen atmosphere before launch proved to be a factor in a fatal fire hazard in Apollo, contributing to the deaths of the entire crew of Apollo 1 during a 1967 ground test. After this, NASA revised its procedure to use a nitrogen/oxygen mix at zero cabin altitude at launch, but kept the low-pressure pure oxygen atmosphere at 5 psi (0.34 bar) in space.[30]

After the Apollo program, the United States used "a 74-percent oxygen and 26-percent nitrogen breathing mixture" at 5 psi (0.34 bar) for Skylab,[31] and a cabin atmosphere of 14.5 psi (1.00 bar) for the Space Shuttle orbiter and the International Space Station.[32]

Mechanics

[edit]

An airtight fuselage is pressurized using a source of compressed air and controlled by an environmental control system (ECS). The most common source of compressed air for pressurization is bleed air from the compressor stage of a gas turbine engine; from a low or intermediate stage or an additional high stage, the exact stage depending on engine type. By the time the cold outside air has reached the bleed air valves, it has been heated to around 200 °C (392 °F). The control and selection of high or low bleed sources is fully automatic and is governed by the needs of various pneumatic systems at various stages of flight. Piston-engine aircraft require an additional compressor, see diagram right.[34]

The part of the bleed air that is directed to the ECS is then expanded to bring it to cabin pressure, which cools it. A final, suitable temperature is then achieved by adding back heat from the hot compressed air via a heat exchanger and air cycle machine known as a PAC (Pressurization and Air Conditioning) system. In some larger airliners, hot trim air can be added downstream of air-conditioned air coming from the packs if it is needed to warm a section of the cabin that is colder than others.

At least two engines provide compressed bleed air for all the plane's pneumatic systems, to provide full redundancy. Compressed air is also obtained from the auxiliary power unit (APU), if fitted, in the event of an emergency and for cabin air supply on the ground before the main engines are started. Most modern commercial aircraft today have fully redundant, duplicated electronic controllers for maintaining pressurization along with a manual back-up control system.

All exhaust air is dumped to atmosphere via an outflow valve, usually at the rear of the fuselage. This valve controls the cabin pressure and also acts as a safety relief valve, in addition to other safety relief valves. If the automatic pressure controllers fail, the pilot can manually control the cabin pressure valve, according to the backup emergency procedure checklist. The automatic controller normally maintains the proper cabin pressure altitude by constantly adjusting the outflow valve position so that the cabin altitude is as low as practical without exceeding the maximum pressure differential limit on the fuselage. The pressure differential varies between aircraft types, typical values are between 540 hPa (7.8 psi) and 650 hPa (9.4 psi).[35] At 39,000 ft (11,887 m), the cabin pressure would be automatically maintained at about 6,900 ft (2,100 m), (450 ft (140 m) lower than Mexico City), which is about 790 hPa (11.5 psi) of atmosphere pressure.[34]

Some aircraft, such as the Boeing 787 Dreamliner, have re-introduced electric compressors previously used on piston-engined airliners to provide pressurization.[36][37] The use of electric compressors increases the electrical generation load on the engines and introduces a number of stages of energy transfer;[38] therefore, it is unclear whether this increases the overall efficiency of the aircraft air handling system. They do, however, remove the danger of chemical contamination of the cabin, simplify engine design, avert the need to run high pressure pipework around the aircraft, and provide greater design flexibility.

Unplanned decompression

[edit]

Unplanned loss of cabin pressure at altitude/in space is rare but has resulted in a number of fatal accidents. Failures range from sudden, catastrophic loss of airframe integrity (explosive decompression) to slow leaks or equipment malfunctions that allow cabin pressure to drop.

Any failure of cabin pressurization above 10,000 ft (3,000 m) requires an emergency descent to 10,000 ft or the closest to that while maintaining the minimum sector altitude (MSA), and the deployment of an oxygen mask for each seat. The oxygen systems have sufficient oxygen for all on board and give the pilots adequate time to descend to below 10,000 ft. Without emergency oxygen, hypoxia may lead to loss of consciousness and a subsequent loss of control of the aircraft. Modern airliners include a pressurized pure oxygen tank in the cockpit, giving the pilots more time to bring the aircraft to a safe altitude. The time of useful consciousness varies according to altitude. As the pressure falls the cabin air temperature may also plummet to the ambient outside temperature with a danger of hypothermia or frostbite.

For airliners that need to fly over terrain that does not allow reaching the safe altitude within a maximum of 30 minutes, pressurized oxygen bottles are mandatory since the chemical oxygen generators fitted to most planes cannot supply sufficient oxygen.

In jet fighter aircraft, the small size of the cockpit means that any decompression will be very rapid and would not allow the pilot time to put on an oxygen mask. Therefore, fighter jet pilots and aircrew are required to wear oxygen masks at all times.[39]

On June 30, 1971, the crew of Soyuz 11, Soviet cosmonauts Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev were killed after the cabin vent valve accidentally opened before atmospheric re-entry.[40][41]

History

[edit]

The aircraft that pioneered pressurized cabin systems include:

- Packard-Le Père LUSAC-11, (1920, a modified French design, not actually pressurized but with an enclosed, oxygen enriched cockpit)

- Engineering Division USD-9A, a modified Airco DH.9A (1921 – the first aircraft to fly with the addition of a pressurized cockpit module)[42]

- Junkers Ju 49 (1931 – a German experimental aircraft purpose-built to test the concept of cabin pressurization)

- Farman F.1000 (1932 – a French record breaking pressurized cockpit, experimental aircraft)

- Chizhevski BOK-1 (1936 – a Russian experimental aircraft)

- Lockheed XC-35 (1937 – an American pressurized aircraft. Rather than a pressure capsule enclosing the cockpit, the monocoque fuselage skin was the pressure vessel.)

- Renard R.35 (1938 – the first pressurized piston airliner)

- Boeing 307 Stratoliner (1938 – the first pressurized airliner to enter commercial service)

- Lockheed Constellation (1943 – the first pressurized airliner in wide service)

- Boeing 377 Stratocruiser (1947-the first pressurized double-decker plane to see long - range commercial service)

- Avro Tudor (1946 – first British pressurized airliner)

- de Havilland Comet (British, Comet 1 1949 – the first jetliner, Comet 4 1958 – resolving the Comet 1 problems)

- Tupolev Tu-144 and Concorde (1968 USSR and 1969 Anglo-French respectively – first to operate at very high altitude)

- Cessna P210 (1978) First commercially successful pressurized single-engine aircraft[43]

- SyberJet SJ30 (2005) First civilian business jet to certify 12.0 psi pressurization system allowing for a sea level cabin at 41,000 ft (12,497 m).[44]

The first airliner to enter commercial service with a pressurized cabin was the Boeing 307 Stratoliner, built in 1938, prior to World War II, though only ten were produced before the war interrupted production. The 307's "pressure compartment was from the nose of the aircraft to a pressure bulkhead in the aft just forward of the horizontal stabilizer."[45]

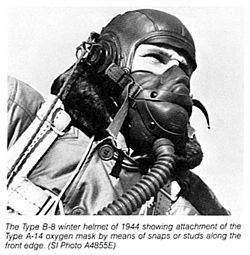

World War II was a catalyst for aircraft development. Initially, the piston aircraft of World War II, though they often flew at very high altitudes, were not pressurized and relied on oxygen masks.[46] This became impractical with the development of larger bombers where crew were required to move about the cabin. The first bomber built with a pressurised cabin for high altitude use was the Vickers Wellington Mark VI in 1941 but the RAF changed policy and instead of acting as Pathfinders the aircraft were used for other purposes. The US Boeing B-29 Superfortress long range strategic bomber was first into bomb service. The control system for this was designed by Garrett AiResearch Manufacturing Company, drawing in part on licensing of patents held by Boeing for the Stratoliner.[47]

Post-war piston airliners such as the Lockheed Constellation (1943) made the technology more common in civilian service. The piston-engined airliners generally relied on electrical compressors to provide pressurized cabin air. Engine supercharging and cabin pressurization enabled aircraft like the Douglas DC-6, the Douglas DC-7, and the Constellation to have certified service ceilings from 24,000 to 28,400 ft (7,315 to 8,656 m). Designing a pressurized fuselage to cope with that altitude range was within the engineering and metallurgical knowledge of that time. The introduction of jet airliners required a significant increase in cruise altitudes to the 30,000–41,000 ft (9,144–12,497 m) range, where jet engines are more fuel efficient. That increase in cruise altitudes required far more rigorous engineering of the fuselage, and in the beginning not all the engineering problems were fully understood.

The world's first commercial jet airliner was the British de Havilland Comet (1949) designed with a service ceiling of 36,000 ft (11,000 m). It was the first time that a large diameter, pressurized fuselage with windows had been built and flown at this altitude. Initially, the design was very successful but two catastrophic airframe failures in 1954 resulting in the total loss of the aircraft, passengers and crew grounded what was then the entire world jet airliner fleet. Extensive investigation and groundbreaking engineering analysis of the wreckage led to a number of very significant engineering advances that solved the basic problems of pressurized fuselage design at altitude. The critical problem proved to be a combination of an inadequate understanding of the effect of progressive metal fatigue as the fuselage undergoes repeated stress cycles coupled with a misunderstanding of how aircraft skin stresses are redistributed around openings in the fuselage such as windows and rivet holes.

The critical engineering principles concerning metal fatigue learned from the Comet 1 program[48] were applied directly to the design of the Boeing 707 (1957) and all subsequent jet airliners. For example, detailed routine inspection processes were introduced, in addition to thorough visual inspections of the outer skin, mandatory structural sampling was routinely conducted by operators; the need to inspect areas not easily viewable by the naked eye led to the introduction of widespread radiography examination in aviation; this also had the advantage of detecting cracks and flaws too small to be seen otherwise.[49] Another visibly noticeable legacy of the Comet disasters is the oval windows on every jet airliner; the metal fatigue cracks that destroyed the Comets were initiated by the small radius corners on the Comet 1's almost square windows.[50][51] The Comet fuselage was redesigned and the Comet 4 (1958) went on to become a successful airliner, pioneering the first transatlantic jet service, but the program never really recovered from these disasters and was overtaken by the Boeing 707.[52][53]

Even following the Comet disasters, there were several subsequent catastrophic fatigue failures attributed to cabin pressurisation. Perhaps the most prominent example was Aloha Airlines Flight 243, involving a Boeing 737-200.[54] In this case, the principal cause was the continued operation of the specific aircraft despite having accumulated 35,496 flight hours prior to the accident, those hours included over 89,680 flight cycles (takeoffs and landings), owing to its use on short flights;[55] this amounted to more than twice the number of flight cycles that the airframe was designed to endure.[56] Aloha 243 was able to land despite the substantial damage inflicted by the decompression, which had resulted in the loss of one member of the cabin crew; the incident had far-reaching effects on aviation safety policies and led to changes in operating procedures.[56]

The supersonic airliner Concorde had to deal with particularly high pressure differentials because it flew at unusually high altitude (up to 60,000 ft (18,288 m)) and maintained a cabin altitude of 6,000 ft (1,829 m).[57] Despite this, its cabin altitude was intentionally maintained at 6,000 ft (1,829 m).[58] This combination, while providing for increasing comfort, necessitated making Concorde a significantly heavier aircraft, which in turn contributed to the relatively high cost of a flight. Unusually, Concorde was provisioned with smaller cabin windows than most other commercial passenger aircraft in order to slow the rate of decompression in the event of a window seal failing.[59] The high cruising altitude also required the use of high pressure oxygen and demand valves at the emergency masks unlike the continuous-flow masks used in conventional airliners.[60] The FAA, which enforces minimum emergency descent rates for aircraft, determined that, in relation to Concorde's higher operating altitude, the best response to a pressure loss incident would be to perform a rapid descent.[61]

The designed operating cabin altitude for new aircraft is falling and this is expected to reduce any remaining physiological problems. Both the Boeing 787 Dreamliner and the Airbus A350 XWB airliners have made such modifications for increased passenger comfort. The 787's internal cabin pressure is the equivalent of 6,000 ft (1,829 m) altitude resulting in a higher pressure than for the 8,000 ft (2,438 m) altitude of older conventional aircraft;[62] according to a joint study performed by Boeing and Oklahoma State University, such a level significantly improves comfort levels.[63][64] Airbus has stated that the A350 XWB provides for a typical cabin altitude at or below 6,000 ft (1,829 m), along with a cabin atmosphere of 20% humidity and an airflow management system that adapts cabin airflow to passenger load with draught-free air circulation.[65] The adoption of composite fuselages eliminates the threat posed by metal fatigue that would have been exacerbated by the higher cabin pressures being adopted by modern airliners, it also eliminates the risk of corrosion from the use of greater humidity levels.[62]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Brain, Marshall (April 12, 2011). "How Airplane Cabin Pressurization Works". How Stuff Works. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ Ciolac, Alin. "Why do aircraft use cabin pressurization". Honeywell Aerospace Technologies. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ a b rmjg20 (2012-06-09). "The DeHavilland Comet Crash". Aerospace Engineering Blog. Archived from the original on 2022-09-10. Retrieved 2022-08-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ FAA (1989). Aircraft Accident Report – Aloha Airlines, Flight 243, Boeing 737-200, N73711, near Maui, Hawaii, April 28, 1988. FAA. p. 1.

- ^ K. Baillie and A. Simpson. "Altitude oxygen calculator". Retrieved 2006-08-13. – Online interactive altitude oxygen calculator

- ^ "Barotrauma What is it?". Harvard Health Publishing. Harvard Medical School. December 2018. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

On an airplane, barotrauma to the ear – also called aero-otitis or barotitis – can happen as the plane descends for landing.

- ^ Auld, D. J.; Srinivas, K. (2008). "Properties of the Atmosphere". Archived from the original on 2013-06-09. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ "Chapter 7: Aircraft Systems". Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA-H-8083-25B ed.). Federal Aviation Administration. 2016-08-24. p. 36. Archived from the original on 2023-06-20.

- ^ Medical Manual 9th Edition (PDF). International Air Transport Association. ISBN 978-92-9229-445-8.

- ^ Bagshaw M (2007). "Commercial aircraft cabin altitude". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 100 (2): 64. doi:10.1177/014107680710000207. PMC 1790988. PMID 17277266.

- ^ "Commercial Airliner Environmental Control System: Engineering Aspects of Cabin Air Quality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-24.

- ^ "Manufacturers aim for more comfortable cabin climate". Flightglobal. 19 Mar 2012.

- ^ "Bombardier's Stretching Range on Global Express Global Express XRS". Aero-News Network. October 7, 2003.

- ^ "Bombardier Global Express XRS Factsheet" (PDF). Bombardier. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-16. Retrieved 2012-01-09.

- ^ "Aircraft Environmental Control Systems" (PDF). Carleton University. 2003.

- ^ Flight Test: Emivest SJ30 – Long-range rocket Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ SJ30-2, United States of America Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ "Airlines are cutting costs – Are patients with respiratory diseases paying the price?". European Respiratory Society. 2010.

- ^ "Final Policy FAR Part 25 Sec. 25.841 07/05/1996|Attachment 4". Archived from the original on 2011-10-22. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ^ a b "FARs, 14 CFR, Part 25, Section 841".

- ^ a b "Exemption No. 8695". Renton, Washington: Federal Aviation Administration. 2006-03-24. Archived from the original on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ Steve Happenny (2006-03-24). "PS-ANM-03-112-16". Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on 2011-10-22. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ^ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft (Second ed.). New York: MacMillan. p. 256.

- ^ Gatland, p. 134

- ^ Catchpole, John (2001). Project Mercury – NASA's First Manned Space Programme. Chichester, UK: Springer Praxis. p. 410. ISBN 1-85233-406-1.

- ^ Giblin, Kelly A. (Spring 1998). "Fire in the Cockpit!". American Heritage of Invention & Technology. 13 (4). Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ Gatland, p. 264

- ^ Gatland, p. 269

- ^ Gatland, p. 278, 284

- ^ "The Apollo 1 Fire –".

- ^ Belew, Leland F., ed. (1977). "2. Our First Space Station". SP-400 Skylab: Our First Space Station. Washington DC: NASA. p. 18. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ Gernhardt, Michael L.; Dervay, Joseph P.; Waligora, James M.; Fitzpatrick, Daniel T.; Conkin, Johnny (2013). "5.4 Extravehicular Activities" (PDF). EVA Operations. Washington DC: NASA. p. 1.

- ^ "Chapter 7: Aircraft Systems". Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA-H-8083-25B ed.). Federal Aviation Administration. 2016-08-24. pp. 34–35. Archived from the original on 2023-06-20.

- ^ a b "Commercial Airliner Environmental Control System: Engineering Aspects of Cabin Air". 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012.

- ^ "Differential Pressure Characteristics of Aircraft".

- ^ Ogando, Joseph, ed. (June 4, 2007). "Boeing's 'More Electric' 787 Dreamliner Spurs Engine Evolution: On the 787, Boeing eliminated bleed air and relied heavily on electric starter generators". Design News. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ^ Dornheim, Michael (March 27, 2005). "Massive 787 Electrical System Pressurizes Cabin". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- ^ "Boeing 787 from the Ground Up"

- ^ Jedick MD/MBA, Rocky (28 April 2013). "Hypoxia". goflightmedicine.com. Go Flight Medicine. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Triumph and Tragedy of Soyuz 11". Time. 12 July 1971. Archived from the original on March 18, 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- ^ "Soyuz 11". Encyclopedia Astronautica. 2007. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- ^ Harris, Brigader General Harold R. USAF (Ret.), “Sixty Years of Aviation History, One Man's Remembrance,” journal of the American Aviation Historical Society, Winter, 1986, p 272-273

- ^ New, Paul (May 17, 2018). "All Blown Up". Tennessee Aircraft Services. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

The P210 wasn't the first production pressurized single engine aircraft, but it was definitely the first successful one.

- ^ Cornelisse, Diana G. (2002). Splended Vision, Unswerving Purpose; Developing Air Power for the United States Air Force During the First Century of Powered Flight. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio: U.S. Air Force Publications. pp. 128–29. ISBN 0-16-067599-5.

- ^ William A. Schoneberger and Robert R. H. Scholl, Out of Thin Air: Garrett's First 50 Years, Phoenix: Garrett Corporation, 1985 (ISBN 0-9617029-0-7), p. 275.

- ^ Some extremely high flying aircraft such as the Westland Welkin used partial pressurization to reduce the effort of using an oxygen mask.

- ^ Seymour L. Chapin (August 1966). "Garrett and Pressurized Flight: A Business Built on Thin Air". Pacific Historical Review. 35 (3): 329–43. doi:10.2307/3636792. JSTOR 3636792.

- ^ R.J. Atkinson, W.J. Winkworth and G.M. Norris (1962). "Behaviour of Skin Fatigue Cracks at the Corners of Windows in a Comet Fuselage". Aeronautical Research Council Reports and Memoranda. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.226.7667.

- ^ Jefford, C.G., ed. The RAF and Nuclear Weapons, 1960–1998. London: Royal Air Force Historical Society, 2001. pp. 123–125.

- ^ Davies, R.E.G. and Philip J. Birtles. Comet: The World's First Jet Airliner. McLean, Virginia: Paladwr Press, 1999. ISBN 1-888962-14-3. pp. 30–31.

- ^ Munson, Kenneth. Civil Airliners since 1946. London: Blandford Press, 1967. p. 155.

- ^ "Milestones in Aircraft Structural Integrity". ResearchGate. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Faith, Nicholas. Black Box: Why Air Safety is no Accident, The Book Every Air Traveller Should Read. London: Boxtree, 1996. ISBN 0-7522-2118-3. p. 72.

- ^ "Aircraft Accident Report AAR8903: Aloha Airlines, Flight 243, Boeing 737-200, N73711" (PDF). NTSB. 14 June 1989.

- ^ Aloha Airlines Flight 243 incident report - AviationSafety.net, accessed July 5, 2014.

- ^ a b "Aircraft Accident Report, Aloha Airlines Flight 243, Boeing 737-100, N73711, Near Maui, Hawaii, April 28, 1998" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. June 14, 1989. NTSB/AAR-89/03. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Hepburn, A.N. (1967). "Human Factors in the Concord". Occupational Medicine. 17 (2): 47–51. doi:10.1093/occmed/17.2.47.

- ^ Hepburn, A.N. (1967). "Human Factors in the Concorde". Occupational Medicine. 17 (2): 47–51. doi:10.1093/occmed/17.2.47.

- ^ Nunn, John Francis (1993). Nunn's applied respiratory physiology. Butterworth-Heineman. p. 341. ISBN 0-7506-1336-X.

- ^ Nunn 1993, p. 341.

- ^ Happenny, Steve (24 March 2006). "Interim Policy on High Altitude Cabin Decompression – Relevant Past Practice". Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ a b Adams, Marilyn (November 1, 2006). "Breathe easy, Boeing says". USA Today.

- ^ Croft, John (July 2006). "Airbus and Boeing spar for middleweight" (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- ^ "Boeing 7E7 Offers Preferred Cabin Environment, Study Finds" (Press release). Boeing. July 19, 2004. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ "Taking the lead: A350XWB presentation" (PDF). EADS. December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27.

General references

[edit]- Seymour L. Chapin (August 1966). "Garrett and Pressurized Flight: A Business Built on Thin Air". Pacific Historical Review. 35 (3): 329–43. doi:10.2307/3636792. JSTOR 3636792.

- Seymour L. Chapin (July 1971). "Patent Interferences and the History of Technology: A High-flying Example". Technology and Culture. 12 (3): 414–46. doi:10.2307/3102997. JSTOR 3102997. S2CID 112829106.

- Cornelisse, Diana G. Splendid Vision, Unswerving Purpose; Developing Air Power for the United States Air Force During the First Century of Powered Flight. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio: U.S. Air Force Publications, 2002. ISBN 0-16-067599-5. pp. 128–29.

- Portions from the United States Naval Flight Surgeon's Manual

- "121 Dead in Greek Air Crash", CNN

External links

[edit]Cabin pressurization

View on GrokipediaPhysiological Need

Human Response to Low Pressure

As atmospheric pressure decreases with increasing altitude, the partial pressure of oxygen (PO₂) in inspired air diminishes, impairing oxygen uptake in the lungs and subsequent delivery to tissues. At sea level, PO₂ is approximately 160 mmHg, but it halves to about 80 mmHg at 18,000 feet (5,500 m), effectively reducing the oxygen fraction to an equivalent of 10.5% at sea-level pressure despite the constant 21% oxygen composition in air.[7][8] This hypobaric hypoxia triggers physiological responses such as hyperventilation and increased heart rate, but above 10,000 feet (3,000 m), symptoms emerge including euphoria, impaired judgment, headache, cyanosis, visual impairment, and drowsiness, which can progress to unconsciousness without intervention.[8][9] The severity of hypoxia is quantified by the time of useful consciousness (TUC), defined as the maximum period after sudden oxygen deprivation during which an individual can perform rational, life-saving actions. TUC shortens nonlinearly with altitude due to rapid arterial oxygen desaturation; for instance, it ranges from 3–5 minutes at 25,000 feet to mere 9–15 seconds at 45,000 feet. Representative TUC durations, based on unacclimatized individuals at rest, are summarized below:| Altitude (feet MSL) | TUC Duration |

|---|---|

| 25,000 | 3–5 minutes |

| 30,000 | 1–2 minutes |

| 35,000 | 30–60 seconds |

| 40,000 | 15–20 seconds |

| 45,000 | 9–15 seconds |