Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alabama Legislature

View on Wikipedia

The Alabama Legislature is the legislative branch of the government of the U.S. state of Alabama. It is a bicameral body composed of the House of Representatives and Senate. It is one of the few state legislatures in which members of both chambers serve four-year terms and in which all are elected in the same cycle. The most recent election was on November 8, 2022. The new legislature assumes office immediately following the certification of the election results by the Alabama Secretary of State which occurs within a few days following the election.

Key Information

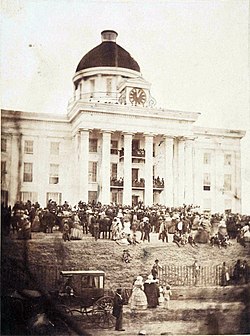

The Legislature meets in the Alabama State House in Montgomery. The original capitol building, located nearby, has not been used by the Legislature on a regular basis since 1985, when it closed for renovations. In the 21st century, it serves as the seat of the executive branch as well as a museum.

History

[edit]

Establishment

[edit]The Alabama Legislature was founded in 1818 as a territorial legislature for the Alabama Territory. Following the federal Alabama Enabling Act of 1819 and the successful passage of the first Alabama Constitution in the same year, the Alabama General Assembly became a fully fledged state legislature upon the territory's admission as a state. The term both of state representatives and of state senators is four years.

The General Assembly was one of the 11 state legislatures of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. Following the state's secession from the Union in January 1861, delegates from across the South met at the state capital of Montgomery to create the Confederate government. Between February and May 1861, Montgomery served as the Confederacy's capital, where Alabama state officials let members of the new Southern federal government make use of its offices. The Provisional Confederate Congress met for three months inside the General Assembly's chambers at the Alabama State Capitol. Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as the Confederacy's first and only president on the steps of the capitol.

However, following complaints from Southerners over Montgomery's uncomfortable conditions and, more importantly, following Virginia's entry into the Confederacy, the Confederate government moved to Richmond in May 1861.

Reconstruction era

[edit]Following the Confederacy's defeat in 1865, the state government underwent a transformation following emancipation of enslaved African Americans, and constitutional amendments to grant them citizenship and voting rights. Congress dominated the next period of Reconstruction, which some historians attribute to Radical Republicans. For the first time, African-Americans could vote and were elected to the legislature. Republicans were elected to the state governorship and dominated the General Assembly; more than eighty percent of the members were white.

In 1867, a state constitutional convention was called, and a biracial group of delegates worked on a new constitution. The biracial legislature passed a new constitution in 1868, establishing public education for the first time, as well as institutions such as orphanages and hospitals to care for all the citizens of the state. This constitution, which affirmed the franchise for freedmen, enabled Alabama to be readmitted into the United States in 1868.

As in other states during Reconstruction, former Confederate and insurgent "redeemer" forces from the Democratic Party gradually overturned the Republicans by force and fraud. Elections were surrounded by violence as paramilitary groups aligned with the Democrats worked to suppress black Republican voting. By the 1874 state general elections, the General Assembly was dominated by White Americans Bourbon Democrats from the elite planter class.

Both the resulting 1875 and 1901 constitutions disenfranchised African-Americans, and the 1901 also adversely affected thousands of poor White Americans, by erecting barriers to voter registration. Late in the 19th century, a Populist-Republican coalition had gained three congressional seats from Alabama and some influence in the state legislature. After suppressing this movement, Democrats returned to power, gathering support under slogans of white supremacy. They passed a new constitution in 1901 that disenfranchised most African-Americans and tens of thousands of poor White Americans, excluding them from the political system for decades into the late 20th century. The Democratic-dominated legislature passed Jim Crow laws creating legal segregation and second-class status for African-Americans. The 1901 Constitution changed the name of the General Assembly to the Alabama Legislature. (Amendment 427 to the Alabama Constitution designated the State House as the official site of the legislature.)

Civil Rights era

[edit]Following World War II, the state capital was a site of important civil rights movement activities. In December 1955 Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white passenger on a segregated city bus. She and other African-American residents conducted the more than year-long Montgomery bus boycott to end discriminatory practices on the buses, 80% of whose passengers were African Americans. Both Parks and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a new pastor in the city who led the movement, gained national and international prominence from these events.

Throughout the late 1950s and into the 1960s, the Alabama Legislature and a series of succeeding segregationist governors massively resisted school integration and demands of social justice by civil rights protesters.

During this period, the Legislature passed a law authorizing the Alabama State Sovereignty Commission. Mirroring Mississippi's similarly named authority, the commission used taxpayer dollars to function as a state intelligence agency: it spied on Alabama residents suspected of sympathizing with the civil rights movement (and classified large groups of people, such as teachers, as potential threats). It kept lists of suspected African-American activists and participated in economic boycotts against them, such as getting suspects fired from jobs and evicted from rentals, disrupting their lives and causing financial distress. It also passed on the names of suspected activists to local governments and citizens' groups such as the White Citizens Council, which also followed tactics to penalize activists and enforce segregation.

Following a federal constitutional amendment banning use of poll taxes in federal elections, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 authorizing federal oversight and enforcement of fair registration and elections, and the 1966 US Supreme Court ruling that poll taxes at any level were unconstitutional, African Americans began to register and vote again in numbers proportional to their population. They were elected again to the state legislature and county and city offices for the first time since the late 19th century.

Federal court cases increased political representation for all residents of the state in a different way. Although required by its state constitution to redistrict after each decennial census, the Alabama legislature had not done so from the turn of the century to 1960. In addition, state senators were elected from geographic counties. As a result, representation in the legislature did not reflect the state's changes in population, and was biased toward rural interests. It had not kept up with the development of major urban, industrialized cities such as Birmingham and Tuscaloosa. Their residents paid much more in taxes and revenues to the state government than they received in services. Services and investment to support major cities had lagged due to under-representation in the legislature.

Under the principle of one man, one vote, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims (1964) that both houses of any state legislature need to be based on population, with apportionment of seats redistricted as needed according to the decennial census.[2] This was a challenge brought by citizens of Birmingham. When this ruling was finally implemented in Alabama by court order in 1972, it resulted in the districts including major industrial cities gaining more seats in the legislature.[citation needed]

In May 2007, the Alabama Legislature officially apologized for slavery, making it the fourth Deep South state to do so.[citation needed]

Constitutions

[edit]Alabama has had a total of seven different state constitutions, passed in 1819, 1861, 1865, 1868, 1875, 1901, and 2022. The 1901 constitution had so many amendments, most related to decisions on county-level issues (due to the Alabama Legislature centralizing power at the state level, denying home rule for all but a handful of counties and cities), that it became the longest written constitution in both the United States and the world. A new constitution was adopted in 2022 to remove some Jim Crow-era provisions that were struck down, along with some obsolete provisions (such as one on how to annex foreign territory), and to reorganize the content.

Due to the suppression of black voters after Reconstruction, and especially after passage of the 1901 disenfranchising constitution, most African-Americans and tens of thousands of poor White Americans were excluded from voting for decades.[3][4] After Reconstruction ended no African-Americans served in the Alabama Legislature until 1970 when two black majority districts in the House elected Thomas Reed and Fred Gray. As of the 2018 election, the Alabama House of Representatives has 27 African-American members and the Alabama State Senate has 7 African-American members.

Most African-Americans did not regain the power to vote until after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Before that, many left the state in the Great Migration to northern and midwestern cities. Since the late 20th century, the white majority in the state has voted increasingly Republican. In the 2010 elections, Republicans won majorities in both of Alabama's state legislative chambers, which had both had Democratic majorities since 1874.

Organization

[edit]The Alabama Legislature convenes in regular annual sessions on the first Tuesday in February, except during the first year of the four-year term, when the session begins on the first Tuesday in March. In the last year of a four-year term, the legislative session begins on the second Tuesday in January. The length of the regular session is limited to 30 meeting days within a period of 105 calendar days. Session weeks consist of meetings of the full chamber and committee meetings.

The Governor of Alabama can call, by proclamation, special sessions of the Alabama Legislature and must list the subjects to be considered. Special sessions are limited to 12 legislative days within a 30 calendar day span. In a regular session, bills may be enacted on any subject. In a special session, legislation must be enacted only on those subjects which the governor announces on their proclamation or "call." Anything not in the "call" requires a two-thirds vote of each house to be enacted.

Legislative process

[edit]Alabama's lawmaking process differs somewhat from the other 49 states.

Notice and introduction of bills

[edit]Prior to the introduction of bills that apply to specific, named localities, the Alabama Constitution requires publication of the proposal in a newspaper in the counties to be affected. The proposal must be published for four consecutive weeks and documentation must be provided to show that the notice was posted. The process is known as "notice and proof."

Article 4, Section 45 of the state constitution mandates that each bill may only pertain to one subject, clearly stated in the bill title, "except general appropriation bills, general revenue bills, and bills adopting a code, digest, or revision of statutes".

Committees

[edit]As with other legislative bodies throughout the world, the Alabama legislature operates mainly through committees when considering proposed bills. The Constitution of Alabama states that no bill may be enacted into law until it has been referred to, acted upon by, and returned from, a standing committee in each house. Reference to committee immediately follows the first reading of the bill. Bills are referred to committees by the presiding officer.

The state constitution authorizes each house to determine the number of committees, which varies from quadrennial session to session. Each committee is set up to consider bills relating to a particular subject.

Legislative Council

[edit]The Alabama legislature has a Legislative Council, which is a permanent or continuing interim committee, composed as follows:

- From the Senate, the Lieutenant Governor and President Pro-Tempore, the Chairmen of Finance and Taxation, Rules, Judiciary, and Governmental Affairs, and six Senators elected by the Senate;

- From the House of Representatives, the Speaker and Speaker Pro-Tempore, the Chairmen of Ways and Means, Rules, Judiciary, and Local Government, and six Representatives elected by the House.

- The majority and minority leaders of each house.

The Legislative Council meets at least once quarterly to consider problems for which legislation may be needed, and to make recommendations for the next legislative session.

Committee reports

[edit]After a committee completes work on a bill, it reports the bill to the appropriate house during the "reports of committees" in the daily order of business. Reported bills are immediately given a second reading. The houses do not vote on a bill at the time it is reported; however, reported bills are placed on the calendar for the next legislative day. The second reading is made by title only. Local bills concerning environmental issues affecting more than one political subdivision of the state are given a second reading when reported from the local legislation committee and re-referred to a standing committee where they are then considered as a general bill. Bills concerning gambling are also re-referred when reported from the local legislation committee but they continue to be treated as local bills. When reported from the second committee, these bills are referred to the calendar and do not require another second reading.

The regular calendar is a list of bills that have been favorably reported from committee and are ready for consideration by the membership of the entire house.

Bills are listed on the calendar by number, sponsor, and title, in the order in which they are reported from committee. They must be considered for a third reading in that order unless action is taken to consider a bill out of order. Important bills are brought to the top of the calendar by special orders or by suspending the rules. To become effective, the resolution setting special orders must be adopted by a majority vote of the house. These special orders are recommended by the Rules Committee of each house. The Rules Committee is not restricted to making its report during the Call of Committees, and can report at any time. This enables the committee to determine the order of business for the house. This power makes the Rules Committee one of the most influential of the legislative committees.

Any bill which affects state funding by more than $1,000, and which involves expenditure or collection of revenue, must have a fiscal note. Fiscal notes are prepared by the Legislative Fiscal Office and signed by the chairman of the committee reporting the bill. They must contain projected increases or decreases to state revenue in the event that the bill becomes law.

Third reading

[edit]A bill is placed on the calendar for adoption for its third reading. It is at this third reading of the bill that the whole house gives consideration to its passage. At this time, the bill may be studied in detail, debated, amended, and read at length before final passage.

Once the bill is discussed, each member casts his or her vote, and their name is called alphabetically to record their vote. Since the state's Senate has only 35 members, voting may be done effectively in that house by a roll call of the members. The membership of the House is three times larger, with 105 members; since individual roll-call voice votes are time-consuming, an electronic voting machine is used in the House of Representatives. The House members vote by pushing buttons on their desks, and their votes are indicated by colored lights which flash on a board in the front of the chamber. The board lists each member name and shows how each member voted. The votes are electronically recorded in both houses.

If a majority of the members who are present and voting in each house vote against a bill, or if there is a tie vote,[5] it fails passage. If the majority vote in favor of the bill, its approval is recorded as passing. If amendments are adopted, the bill is sent to the Enrolling and Engrossing Department of that house for engrossment. Engrossment is the process of incorporating amendments into the bill before transmittal to the second house.

Transmission to second house

[edit]A bill that is passed in one house is transmitted, along with a formal message, to the other house. Such messages are always in order and are read (in the second house) at any suitable pause in business. After the message is read, the bill receives its first reading, by title only, and is referred to committee. In the second house, a bill must pass successfully through the same steps of procedure as in the first house. If the second house passes the bill without amendment, the bill is sent back to the house of origin and is ready for enrollment, which is the preparation of the bill in its final form for transmittal to the governor. However, the second house may amend the bill and pass it as amended. Since a bill must pass both houses in the same form, the bill with amendment is sent back to the house of origin for consideration of the amendment. If the bill is not reported from committee or is not considered by the full house, the bill is defeated.

The house of origin, upon return of its amended bill, may take any one of several courses of action. It may concur in the amendment by the adoption of a motion to that effect; then the bill, having been passed by both houses in identical form, is ready for enrollment. Another possibility is that the house of origin may adopt a motion to non-concur in the amendment, at which point the bill dies. Finally, the house of origin may refuse to accept the amendment but request that a conference committee be appointed. The other house usually agrees to the request, and the presiding officer of each house appoints members to the conference committee.

Conference committees

[edit]Conferences committee is empaneled to discusses the points of difference between the two houses' versions of the same bill, and assigned members try to reach an agreement on the content so that the bill can be passed by both houses. If an agreement is reached and if both houses adopt the conference committee's report, the bill is passed. If either house refuses to adopt the report of the conference committee, a motion may be made for further conference. If a conference committee is unable to reach an agreement, it may be discharged, and a new conference committee may be appointed. Highly controversial bills may be referred to several different conference committees. If an agreement is never reached in conference prior to the end of the legislative session, the bill is lost.

When a bill has passed both houses in identical form, it is enrolled. The "enrolled" copy is the official bill, which, after it becomes law, is kept by the Secretary of State for reference in the event of any dispute as to its exact language. Once a bill has been enrolled, it is sent back to the house of origin, where it must be read again (unless this reading is dispensed with by a two-thirds vote), and signed by the presiding officer in the presence of the members. The bill is then sent to the other house where the presiding officer in the presence of all the members of that house also signs it. The bill is then ready for transmittal to the governor.

Presentation to the governor

[edit]The governor may sign legislation, which completes its enactment into law. From this point, the bill becomes an act, and remains the law of the state unless repealed by legislative action, or overturned by a court decision. Governors may veto legislation. Vetoed bills return to the house in which they originated, with a message explaining the governor's objections and suggesting amendments that might remove those objections. The bill is then reconsidered, and if a simple majority of the members of both houses agrees to the proposed executive amendments, it is returned to the governor, as he revised it, for his signature. The governor is also permitted the line-item veto on appropriations bills.

In contrast to the practice of most states and the federal government (which require a supermajority, usually 2/3, to override a veto), a simple majority of the members of each house can choose to approve a vetoed bill precisely as the Legislature originally passed it, in which case it becomes a law over the governor's veto.

If the governor fails to return a bill to the legislative house in which it originated within six days after it was presented (including Sundays), it becomes a law without their signature. This return can be prevented by recession of the Legislature. In that case the bill must be returned within two days after the legislature reassembles, or it becomes a law without the governor's signature.

The bills that reach the governor less than five days before the end of the session may be approved within ten days after adjournment. The bills not approved within that time do not become law. This is known as a "pocket veto". This is the most conclusive form of veto, since state lawmakers have no chance to reconsider the vetoed measure.

Constitutional amendments

[edit]Legislation that would change the state constitution takes the form of a constitutional amendment. A constitutional amendment is introduced and takes the same course as a bill or resolution, except it must be read at length on three different days in each house, must pass each house by a three-fifths vote of the membership, and does not require the approval of the governor. A constitutional amendment passed by the legislature is deposited directly with the Alabama Secretary of State. It is then submitted to voters at an election held not less than three months after the adjournment of the session in which state lawmakers proposed the amendment. The governor announces the election by proclamation, and the proposed amendment and notice of the election must be published in every county for four successive weeks before the election. If a majority of those who vote at the election favor the amendment, it becomes a part of the Alabama Constitution. The result of the election is announced by proclamation of the governor.

Notable members

[edit]- Spencer Bachus, U. S. Representative (1993–2015), Member of Alabama Senate (1983–1984), Member of Alabama House (1984–1987)

- Robert J. Bentley, Governor of Alabama (2011–2017), Member of Alabama House (2002–2011)

- Albert Brewer, Governor of Alabama (1968–1971), Member of Alabama House (1954–1966) and its Speaker (1963–1966)

- Mo Brooks, U. S. Representative (2011–2023), Member of Alabama House (1984–1992)

- Glen Browder, U. S. Representative (1989-1997), Alabama Secretary of State (1987-1989); Member of Alabama House (1983-1986)

- Sonny Callahan, U. S. Representative (1985–2003), Member of Alabama House (1970–1978), Member of Alabama Senate (1978–1982)

- U. W. Clemon, Federal District Judge (1980–2009), Member of Alabama Senate (1974–1980)

- Ben Erdreich, U. S. Representative (1983–1993), Member of Alabama House (1970–1974)

- Euclid T. Rains, Jr., Member of Alabama House (1978–1990), Blind legislator [6]

- Mike Rogers, U. S. Representative (2003–present), Member of Alabama House (1994–2003)

- Benjamin F. Royal, Member of Alabama Senate (1868-1875), Bullock County, served as first African-American State Senator in Alabama history [7]

- Christopher Sheats, U. S. Representative (1873-1875), Member of Alabama House, (1861-1862), Consul to Denmark (1869-1873)

- Richard Shelby, U. S. Senator (1987–2023), U. S. Representative (1979-1987), Member of Alabama Senate (1970–1978)

- George Wallace, Governor of Alabama (1963–1967, 1971–1979, 1983–1987), Member of Alabama House (1946–1953)

- Hattie Hooker Wilkins, Member of Alabama House (1922-1926), Dallas County, first woman in state history to serve in Alabama Legislature[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2020 Legislator Compensation". National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ REYNOLDS v. SIMS, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) Archived May 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, FindLaw, accessed 12 March 2015

- ^ J. Morgan Kousser.The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974

- ^ Glenn Feldman, The Disfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136

- ^ "SECTION 63". Justia Law. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Alabama House of Representatives website (legislature.state.al.us), Past Legislators Roster (1922-2018)

- ^ Bailey, Neither Carpetbaggers nor Scalawags (1991)

- ^ Dance, Gabby; Alabama Political Reporter, 7/24/2019

External links

[edit]Alabama Legislature

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins in Territorial Period and Statehood

The Alabama Territory was organized on March 3, 1817, through an act of the U.S. Congress that divided the Mississippi Territory, with the eastern portion becoming Alabama Territory; President James Monroe appointed William Wyatt Bibb as its first governor.[4] The territorial government included a bicameral legislature comprising a House of Representatives and a smaller Legislative Council serving as the upper house, modeled on earlier territorial structures but with limited membership due to the sparse population.[4] The legislature convened for its inaugural session from January 19 to February 14, 1818, at the Douglas Hotel in St. Stephens, with 13 representatives in the House and only one member, James Titus, in the Legislative Council.[4] This body enacted foundational laws, including the creation of counties, establishment of three judicial districts, authorization of a state bank and a steamboat company, and regulations for land sales and divorce proceedings.[4] A second and final territorial session occurred from November 2 to 21, 1818, again in St. Stephens, expanding to approximately 20 House members while the Council remained minimal; it directed the future capital to Cahaba and conducted a census revealing over 60,000 free white inhabitants, fulfilling prerequisites for statehood petitions.[4] These sessions focused on basic governance amid rapid settlement driven by land availability post-Creek cessions, though the legislature's powers were subordinate to federal oversight and the governor's veto.[4] In response to territorial petitions, President Monroe signed the Enabling Act on March 2, 1819, authorizing a constitutional convention.[4] Delegates—44 in number—met from July 5 to August 2, 1819, in Huntsville, drafting Alabama's first constitution, which established a robust bicameral General Assembly as the dominant branch of state government.[5] The constitution provided for a popularly elected Senate, with members initially staggered into three classes serving one-, two-, or three-year terms, and a House of Representatives elected annually by white male suffrage for those aged 21 and resident in the state for over one year; the legislature held extensive powers, including the ability to override gubernatorial vetoes by simple majority and to elect executive and judicial officers.[5] Congress admitted Alabama to the Union on December 14, 1819, as the 22nd state.[4] The first session of the state General Assembly convened from October 25 to December 17, 1819, in Huntsville as the temporary capital, transitioning from territorial ad hoc lawmaking to formalized state operations under the new framework.[6] Subsequent sessions, such as the second in November–December 1820 at Cahaba, built on this foundation by passing session laws on taxation, infrastructure, and internal governance. This early legislative structure reflected frontier priorities of expansion and local control, with the assembly's supremacy over other branches persisting until later reforms.[5]Antebellum and Civil War Periods

The Alabama Legislature, formally the General Assembly, was established under the 1819 state constitution as a bicameral body comprising a Senate and a House of Representatives, with legislative power vested in these branches to enact laws on matters including emancipation of slaves, which required specific legislative approval despite constitutional empowerment for owners to petition for manumission.[7][8] The constitution imposed no property qualifications on white male suffrage, making the franchise relatively broad for the era, though representation favored rural planter interests amid the cotton-dominated economy.[7] In the antebellum decades from 1820 to 1860, the legislature navigated economic expansion and sectional tensions, chartering state banks in the 1830s to finance internal improvements like railroads and canals, though these efforts contributed to financial instability following the Panic of 1837. Planter elites, controlling much of the assembly through district-based apportionment, prioritized legislation safeguarding slavery, including restrictions on free Black populations and manumission processes that often involved bonds or relocation requirements to prevent social disruption in a state where enslaved people comprised nearly half the population by 1860. Political realignments, such as the 1823 shift away from Federalist influences toward Scots-Irish settler factions, reflected the legislature's responsiveness to yeoman farmers and smallholders alongside large planters, fostering debates over banking regulation and infrastructure funding without centralized executive veto power. As national divisions intensified, the legislature on February 1860 adopted a resolution mandating a state secession convention if a Republican presidential candidate prevailed, anticipating Abraham Lincoln's election.[9] This convention, elected under legislative authorization, convened in Montgomery on January 7, 1861, and four days later passed an ordinance of secession, followed by ratification of a revised state constitution that explicitly protected slave property, prohibited legislative emancipation without owner consent, imposed stricter banking regulations to avert past crises, and curtailed assembly powers relative to the 1819 framework by enhancing gubernatorial appointment roles.[10][11] During the Civil War (1861–1865), the legislature aligned with Confederate objectives, authorizing troop conscription, appropriating funds for state defense, and relocating sessions to Selma in 1863 amid Union threats to Montgomery. The assembly also debated wartime measures like tax levies on cotton exports to finance the effort, though internal divisions emerged over conscription enforcement and state versus Confederate priorities, reflecting Alabama's status as one of the 11 legislatures within the provisional Confederate government formed in February 1861.[10]Reconstruction and Its Reversal

Following the Civil War, Alabama fell under federal military rule as part of the Third Military District under the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which required the state to draft a new constitution guaranteeing black male suffrage and ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment.[12] A constitutional convention convened in Montgomery from November 1867 to March 1868, dominated by Republican delegates including northern transplants, southern Unionists, and newly enfranchised African Americans, resulting in the Constitution of 1868.[13] This document was ratified by voters on February 5, 1868, amid a boycott by most white Democrats, and Congress approved it in June 1868, enabling Alabama's readmission to the Union on July 9, 1868, after the state legislature ratified the Fourteenth Amendment on July 13.[14] The subsequent elections in 1868 produced a Republican-controlled legislature, with the House of Representatives seating 25 African American members out of 97 total and the Senate including at least two, marking substantial black representation for the first time.[15] Over the next decade until 1878, more than 100 African Americans served in the legislature across multiple sessions.[16] The Reconstruction-era legislature enacted reforms such as establishing a statewide public school system, expanding voting rights, and addressing Confederate debt repudiations, but it was plagued by corruption, factionalism, and fiscal policies that tripled property taxes between 1868 and 1872 to fund these initiatives and state debts.[12] These measures, including the creation of the state board of education and funding for railroads, fueled resentment among white taxpayers, who viewed the Republican coalition—comprising scalawags, carpetbaggers, and freedmen—as illegitimate and extractive, exacerbating economic hardships in a war-devastated state.[13] African American legislators, such as those from counties like Mobile and Montgomery, advocated for civil rights and education, but the body as a whole faced accusations of graft, with scandals involving embezzlement and inflated contracts contributing to its unpopularity.[15] Federal enforcement via the Enforcement Acts of 1870-1871 temporarily suppressed violence by groups like the Ku Klux Klan, but ongoing intimidation and economic boycotts eroded Republican support.[17] Opposition coalesced among conservative Democrats, who reformed their party in 1873-1874 and mobilized through paramilitary groups to challenge Republican dominance.[12] The pivotal 1874 elections saw widespread violence, including the Eufaula Riot on November 3, where white Democratic enforcers, numbering around 1,000, attacked black voters and Republicans in Barbour County, killing at least seven and intimidating thousands, effectively nullifying Republican majorities in that area.[18] Similar clashes occurred statewide, with congressional investigations later documenting over 100 violent incidents that suppressed black turnout.[17] Democrats secured a sweeping victory, capturing the governorship with George S. Houston and majorities in both legislative chambers: 80 of 96 House seats and 27 of 33 Senate seats.[12] The Democratic legislature, upon convening in 1875, swiftly reversed Reconstruction policies by slashing taxes, dismantling public education funding, and purging Republican officeholders, while calling a constitutional convention that September to further constrain state government and executive authority.[12] This "Redeemer" regime prioritized fiscal conservatism and white supremacy, effectively ending biracial governance and reducing African American legislative presence to near zero by the late 1870s, though full legal disenfranchisement awaited later constitutions.[13] The shift reflected not only electoral gains but also the exhaustion of federal will to enforce Reconstruction, as national Republican priorities waned amid the disputed 1876 presidential election.[17]Adoption of the 1901 Constitution

In November 1900, the Democratic-controlled Alabama Legislature passed a bill authorizing a statewide referendum and election to convene a constitutional convention, responding to ongoing concerns over the 1875 constitution's provisions for broad suffrage and perceived governmental inefficiencies following Reconstruction.[19] This action reflected Democratic efforts to revise the document amid fears of interracial political alliances between Populists and Republicans that had briefly threatened white supremacy in the 1890s. The convention consisted of 155 delegates, all white Democrats, elected on April 23, 1901.[19] It assembled in Montgomery on May 21, 1901, electing John B. Knox as president, and deliberated for 82 days until adopting the new constitution on September 3, 1901.[20] The document's suffrage article explicitly aimed to disenfranchise African Americans—convention leaders, including Knox, openly stated the goal of eliminating black voters from politics while complying with the Fifteenth Amendment—through cumulative poll taxes, literacy and property requirements, and a temporary grandfather clause favoring whites with pre-1867 voting ancestors.[21] This reduced eligible black voters from over 180,000 in 1900 to approximately 2,980 post-ratification.[22] Ratification occurred via popular vote on November 11, 1901, with 108,613 votes in favor and 81,734 opposed, though turnout was suppressed in black-majority counties through intimidation and fraud.[23] The constitution became effective on November 28, 1901, without further legislative approval, as the process bypassed direct assembly ratification in favor of voter endorsement.[24] It centralized authority in the legislature by curtailing executive appointments, restricting judicial powers, and prohibiting local governments from enacting ordinances conflicting with state law, while embedding mechanisms to preserve Democratic dominance.[20]Jim Crow Era and Mid-20th Century

Following the adoption of the 1901 Constitution, the Alabama Legislature entrenched racial disenfranchisement through statutory implementation of its provisions, including poll taxes, cumulative residency requirements, and literacy tests with grandfather clauses that exempted most white voters while excluding nearly all blacks.[21] By 1903, black voter registration in Alabama had plummeted from over 180,000 in 1900 to fewer than 3,000, enabling unchallenged Democratic Party control of the legislature, which persisted as a one-party system for decades.[21] [25] This dominance allowed the legislature to enact and enforce Jim Crow statutes codifying segregation across public life, such as separate schools mandated by constitutional Section 256 and later reinforced by laws allocating unequal funding that disadvantaged black institutions.[26] [27] The legislature expanded segregation through ordinances and bills in the early 20th century, including streetcar separation laws—first in Mobile in 1902 and statewide by 1909—and bans on interracial marriage embedded in the constitution and upheld by statute.[26] [28] In 1927, it amended racial classification statutes to adopt a "one-drop rule," defining anyone with any African ancestry as black, further rigidifying social divisions.[26] These measures, alongside felony disenfranchisement laws rooted in the 1901 framework targeting "crimes of moral turpitude," systematically suppressed black political participation and legislative influence.[29] The Democratic supermajority, representing primarily white rural interests via malapportioned districts, prioritized policies like agricultural protections and anti-union laws over broader reforms, reflecting the constitution's restrictions on taxing and spending that limited state intervention.[25] In the mid-20th century, amid rising federal pressure post-Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the legislature pursued massive resistance strategies, including a 1956 joint resolution asserting state sovereignty against desegregation mandates and authorizing school closures to evade integration.[30] It repealed compulsory school attendance laws in 1957 to undermine federal enforcement, effectively prioritizing segregation preservation over educational continuity.[30] Voter suppression persisted through white primaries and administrative barriers, maintaining near-total Democratic control—every legislative seat held by Democrats into the 1960s—while blocking civil rights bills until federal intervention via the Voting Rights Act of 1965 began eroding these barriers.[25] [31] This era's legislative actions underscored a commitment to white supremacy, with empirical data showing black representation in the legislature at zero until the late 1960s, despite comprising about 30% of the population.[25]Civil Rights Era and Subsequent Changes

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision on May 17, 1954, which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, the Alabama Legislature enacted measures to obstruct compliance and maintain segregated education. The legislature passed the Alabama Pupil Placement Law (Act 201 of 1955), which authorized school boards to assign students based on purported non-racial criteria such as aptitude, health, and availability of space, effectively allowing de facto segregation to persist despite federal mandates.[32] In 1956, the legislature approved additional statutes empowering local boards to resist desegregation orders and a constitutional amendment that absolved the state of its obligation to provide uniform public education, enabling potential school closures or funding shifts to private institutions as alternatives to integration.[27] These actions exemplified the broader "massive resistance" strategy adopted by Southern legislatures, including Alabama's 1956 ban on NAACP activities within the state to suppress civil rights organizing.[33] The Alabama Legislature also reinforced segregation in other public domains during the 1950s and early 1960s, aligning with executive actions like Governor George Wallace's 1963 inaugural pledge of "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever." Lawmakers passed resolutions of interposition claiming state sovereignty over federal rulings and supported policies such as tuition grants for white students attending private academies to evade court-ordered integration.[34] Federal intervention intensified with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and employment, and the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965, which suspended literacy tests and other discriminatory devices in Alabama, where Black voter registration had languished below 20% prior to the law.[35] The VRA's preclearance requirements under Section 5 subjected Alabama's voting changes to federal oversight, dismantling barriers that had preserved white Democratic dominance in the legislature since the post-Reconstruction era.[36] Post-1965, the VRA catalyzed shifts in legislative composition by boosting Black voter turnout; statewide Black registration rose from approximately 19,000 in 1965 to over 145,000 by 1967, enabling electoral gains. The first African Americans elected to the Alabama Legislature since Reconstruction were attorney Fred Gray and Thomas Reed, both seated in the House of Representatives following the November 3, 1970, elections—Gray representing Tuskegee and Reed Montgomery.[37] This marked the onset of gradual diversification, though representation remained minimal; by 1983, only eight Black members served in a body of 140, reflecting persistent malapportionment addressed by federal courts in Reynolds v. Sims (1964), which mandated one-person, one-vote redistricting.[38] Legislative policies evolved unevenly, with resistance to further integration yielding to compliance under federal pressure, but the Democratic supermajority—rooted in segregationist traditions—persisted until the late 20th century, prioritizing rural interests and limited government over expansive reforms.[37]Republican Takeover and Modern Dynamics

The Republican Party secured majorities in both chambers of the Alabama Legislature for the first time since Reconstruction in the November 2, 2010, general elections, flipping control from long-standing Democratic dominance that had persisted since the late 19th century.[39] [40] This takeover aligned with a national Republican surge amid economic recession concerns and opposition to federal policies under President Barack Obama, resulting in net gains of 17 House seats and 7 Senate seats for Republicans.[41] [42] Post-election, the House composition stood at 72 Republicans to 33 Democrats, while the Senate had 23 Republicans to 12 Democrats, enabling unified Republican leadership under House Speaker Dean Young (later Mike Hubbard) and Senate President Pro Tempore Del Marsh.[43] Republicans consolidated and expanded their control in subsequent elections, achieving supermajorities—defined as at least two-thirds of seats, sufficient to override gubernatorial vetoes and propose constitutional amendments without ballot approval in some cases—by the mid-2010s.[44] In 2014, the party gained additional seats, with the House reaching 72 Republicans and the Senate 25, and further solidified through 2018 and 2022 cycles amid low Democratic competitiveness in rural and suburban districts.[45] [46] Internal challenges, including the 2016 corruption conviction of Speaker Hubbard on ethics violations related to campaign finance, led to leadership transitions but did not erode overall majorities, as replacements like Mac McCutcheon maintained conservative priorities.[47] Under Republican control, the legislature prioritized policies reflecting conservative principles, including strict immigration enforcement via House Bill 56 in 2011, which mandated local cooperation with federal authorities and imposed penalties for employing undocumented workers; fiscal measures like property tax freezes and economic incentives for industry recruitment; and pro-life legislation, such as the 2019 Human Life Protection Act establishing near-total abortion restrictions, later upheld post the 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson decision.[48] Other enactments included expansions of gun rights, school choice initiatives via education savings accounts in 2024, and a 2022 constitutional amendment authorizing a state lottery and gaming regulation to generate revenue for education.[49] In 2025, the session advanced tax relief by reducing the grocery sales tax by one penny and providing paid parental leave for public employees, while addressing IVF access protections following a state Supreme Court ruling.[50] As of the 2025 session, Republicans maintain supermajorities with 77 House seats (out of 105) and 27 Senate seats (out of 35), forming a trifecta with Governor Kay Ivey's administration until term limits and potential 2026 shifts.[51] Dynamics feature streamlined conservative agendas on election integrity, public safety, and limited government, though occasional intra-party tensions over issues like gaming expansion and budget allocations have surfaced; Democratic influence remains marginal, confined to urban districts and procedural opposition.[52] This structure has facilitated over 15 constitutional amendments since 2011, focusing on judicial reforms, debt limits, and rights protections, underscoring a departure from prior Democratic eras marked by expansive government under the 1901 Constitution's constraints.[53]Constitutional and Structural Framework

Sequence of State Constitutions

Alabama adopted its first state constitution on August 2, 1819, following a constitutional convention convened in Huntsville from July 5 to August 2, with no popular ratification required.[54] [55] Modeled closely on the U.S. Constitution and those of other early states, it established a bicameral legislature consisting of a House of Representatives and a Senate, with annual sessions, proportional representation in the House based on white population, and equal county representation in the Senate.[7] The document emphasized separation of powers and limited legislative authority to prevent executive overreach, reflecting frontier democratic ideals amid rapid territorial expansion.[56] The second constitution, adopted in 1861 by a convention that began on January 7, amended the 1819 framework to facilitate Alabama's secession from the Union on January 11 and alignment with the Confederate States.[57] It retained the bicameral structure but incorporated provisions for Confederate loyalty oaths and wartime governance, including expanded legislative powers for appropriations related to defense.[58] The convention reconvened later in 1861 to finalize changes, emphasizing states' rights and slavery protections without altering core legislative representation or term lengths.[59] Following the Civil War, the 1865 constitution was adopted on September 12 by a convention in Montgomery, aiming to repeal secession ordinances and restore Union relations without abolishing slavery initially.[60] [61] It preserved the bicameral legislature's basic form but added requirements for Confederate leaders to swear loyalty oaths for officeholding, effectively purging some from legislative service while maintaining annual sessions and county-based Senate apportionment.[54] The 1868 Reconstruction constitution, drafted by a convention from November 5 to December 6, 1867, and ratified under federal military oversight on February 5, 1868—despite failing popular vote—was imposed as a condition for congressional readmission.[54] [62] It expanded legislative powers to enforce civil rights, including public education funding and debt relief, while introducing biennial sessions and poll taxes; the Senate remained malapportioned by county, but Black representatives gained seats amid enfranchisement of freedmen.[14] The 1875 constitution, replacing the Reconstruction document amid Democratic "Redeemer" control, was drafted by a convention from May 12 to July 3 and ratified by voters on November 16.[54] [63] It curtailed legislative authority by prohibiting special local laws, mandating general legislation, and restricting session lengths to 60 days biennially, reflecting backlash against perceived Reconstruction excesses and fiscal overreach.[64] The bicameral structure persisted, with House seats apportioned by population and Senate by counties, prioritizing rural white interests. The current 1901 constitution, adopted by convention on September 3 and ratified by referendum on November 11 (108,613 to 81,734), took effect November 28.[65] [19] Primarily designed to disenfranchise Black voters through cumulative poll taxes and literacy tests, it further constrained the legislature—renaming it from General Assembly—by banning local or private bills except via constitutional amendment, limiting sessions to 105 cumulative days every three years initially (later adjusted), and requiring segregation in appropriations.[66] Senate representation favored less populous Black Belt counties, entrenching rural dominance over urban growth.[67] Over 950 amendments since have bloated the document, but core legislative limits remain, often criticized for hindering responsive governance.[68]Key Provisions Limiting Government Power

The Alabama Constitution of 1901 imposes structural constraints on the legislature's authority through explicit limitations on session duration, legislative processes, and fiscal activities, reflecting a design to curb potential overreach and promote fiscal discipline. Article IV vests legislative power in a bicameral body but delineates boundaries to prevent expansive or unchecked action, such as prohibiting laws on certain subjects without rigorous procedural hurdles.[69] These provisions stem from the constitution's origins in limiting post-Reconstruction governance, emphasizing decentralized control and voter oversight via frequent amendments rather than statutory flexibility.[70] Session lengths represent a primary temporal restraint: regular sessions convene annually on the first Tuesday in May and are capped at 30 legislative days within a 105-calendar-day window, while special sessions called by the governor are restricted to 12 legislative days within 30 calendar days.[1] This brevity, unaltered in core form since adoption, curtails the volume of legislation and reduces opportunities for prolonged deliberation or logrolling, historically justified as a safeguard against professionalization and corruption.[71] Procedural rules further confine discretion, particularly regarding local and special legislation. Section 93 prohibits the legislature from enacting private or local laws on enumerated matters—including granting divorces, changing names, legitimizing children, or vacating roads—unless a general law proves insufficient and proper notice is published.[72] Where a general law exists or can be enacted, local deviations are barred, with violations rendering acts void; additionally, proposed local bills must be advertised weekly for four weeks in local newspapers, ensuring public scrutiny and often derailing parochial favors.[73] Section 45 mandates that each law embrace but one subject, clearly expressed in its title, preventing omnibus bills or concealed provisions that could expand scope covertly.[69] Fiscal provisions enforce restraint on spending and revenue generation. The general appropriations bill is limited to ordinary executive, legislative, and judicial expenses, requiring itemization and prohibition of extraneous matters like capital outlays or special claims.[69] No money may be drawn from the treasury without a specific appropriation, and expenditures cannot exceed estimated revenues, mandating a balanced approach absent voter-approved debt for emergencies.[74] Taxation faces rigid caps: Article XI limits ad valorem property taxes to half of one percent for state purposes without amendment, bans state-level income or inheritance taxes unless constitutionally authorized (neither of which exists), and restricts municipal rates to one-half of one percent.[74] State debt issuance is confined to suppressing invasion, rebellion, or public defense, not exceeding $300,000 without voter consent via amendment.[74] These mechanisms, requiring over 900 amendments since 1901 for fiscal adjustments, compel legislative deference to constitutional rigidity over policy innovation.[75]Delineation of Legislative Powers

The legislative power of the State of Alabama is vested in a bicameral legislature, designated the General Assembly and comprising a Senate and a House of Representatives, pursuant to Section 44 of Article IV of the 1901 Constitution.[76] This delineation establishes the legislature as the primary authority for enacting statutes, with Article IV (Sections 44 through 111) outlining its composition, procedural requirements, and core functions, while Article III enforces separation of powers by dividing state authority into distinct legislative, executive, and judicial branches, prohibiting any branch from exercising powers belonging to another.[76][77] Article IV grants the legislature authority to determine its own rules of procedure, punish members or others for contempt or disorderly conduct, and expel members with a two-thirds vote, as specified in Section 53.[76] It holds exclusive power to originate revenue bills in the House of Representatives (Section 70) and to appropriate state funds (Section 71), alongside the ability to impeach executive and judicial officers, subject to Senate trial (Article VII, Section 173).[76] The legislature may enact general laws on subjects not prohibited by the constitution, but local or private laws require prior public notice and are restricted on topics such as divorce, lotteries, or changes to corporate charters without explicit compliance (Sections 104-107).[76] Procedural safeguards delineate and constrain these powers, including the requirement that every bill embrace a single subject clearly expressed in its title (Section 45) to prevent logrolling, and a prohibition on passing revenue bills during the final five days of a regular session (Section 70).[76] Unlike more expansive state constitutions, Alabama's framework reflects deliberate restrictions originating from post-Reconstruction reforms, limiting legislative discretion in areas like taxation—which must be uniform across classes—and delegating municipal powers under Dillon's Rule, whereby localities derive authority solely from statutory grants revocable by the General Assembly.[78] These provisions ensure legislative actions align with constitutional bounds, with judicial review available to enforce compliance.[76]Composition and Representation

House of Representatives

The Alabama House of Representatives constitutes the lower chamber of the bicameral Alabama Legislature, comprising 105 members who each represent a single-member district apportioned roughly equally by population following decennial census data.[79] Districts are drawn by the state legislature as regular legislation, subject to gubernatorial veto, with reapportionment occurring after each federal census to reflect population shifts; the most recent redistricting, enacted in 2022 following the 2020 census, aimed to achieve minimal population deviations while adhering to state constitutional requirements for contiguous and compact districts where practicable.[80] [81] Members serve staggered four-year terms without term limits, with elections held in even-numbered years; approximately half the seats are contested every two years to maintain continuity.[82] To qualify for election, candidates must be at least 21 years of age, United States citizens, qualified electors of Alabama, and residents of their district for at least one year preceding the election.[83] As of October 2025, Republicans hold 77 seats and Democrats hold 28, reflecting the chamber's Republican majority achieved in the 2010 elections and solidified in subsequent cycles amid the state's conservative electoral leanings.[79] This partisan composition has enabled Republican leadership to advance policy priorities such as fiscal conservatism and election integrity measures, though Democrats maintain influence in urban and Black Belt districts where population concentrations support competitive races.[51]State Senate

The Alabama State Senate comprises 35 members, each elected from a single-member district apportioned roughly equally by population.[84] Senators serve four-year terms, with elections for all seats occurring simultaneously every four years in even-numbered years.[84] This structure, established under the Alabama Constitution of 1901 as amended, ensures representation aligned with decennial census data, with redistricting handled by the legislature following each federal census.[84] Eligibility to serve as a state senator requires a candidate to be at least 25 years of age at the time of election, a United States citizen, a resident of Alabama for three years immediately preceding the election, a resident of the district for one year prior thereto, and a qualified elector of the state.[84] [85] Additional constitutional prohibitions bar individuals convicted of treason, embezzlement of public funds, bribery, or other infamous crimes from holding office.[84] District boundaries are designed to achieve one person, one vote compliance, with the 35 districts collectively covering the state's approximately 5 million residents as of the 2020 census, averaging about 142,000 constituents per senator.[84] The senate's smaller size relative to the 105-member House facilitates focused deliberation on legislation originating in or significantly amended by the upper chamber. As of October 2025, Republicans occupy 27 seats, while Democrats hold 8, reflecting the party's dominance since gaining full control of the legislature in 2010.[84] This composition has enabled consistent advancement of conservative priorities, including fiscal restraint and election integrity measures, amid Alabama's rural-urban political divide.[84]Qualifications, Terms, and Apportionment

The Alabama House of Representatives consists of 105 members, each elected from single-member districts apportioned based on population data from the decennial United States Census, with redistricting conducted by the state legislature as ordinary legislation subject to gubernatorial veto.[80] The Alabama State Senate comprises 35 members, similarly elected from single-member districts designed to achieve population equality as nearly as practicable while adhering to principles of contiguity and compactness.[86] Apportionment occurs every ten years following the federal census, with the most recent redistricting cycle after the 2020 Census completed in 2021–2022, ensuring districts reflect current demographic shifts without mid-decade adjustments absent court order.[81] Qualifications for election to either chamber are outlined in Section 47 of the Alabama Constitution of 1901, requiring candidates to be qualified electors of the state, at least 21 years old for the House or 25 for the Senate, and residents of their respective district or county for one year immediately preceding the election.[85] Additional statutory requirements include U.S. citizenship, state residency, and registration as a voter, with no felony convictions disqualifying otherwise eligible candidates unless rights have been restored.[83]| Office | Minimum Age | U.S. Citizenship | State Residency | District Residency | Qualified Elector | Term Length | Term Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House of Representatives | 21 | Yes | Yes | 1 year prior | Yes | 4 years | None |

| State Senate | 25 | Yes | Yes | 1 year prior | Yes | 4 years | None |