Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

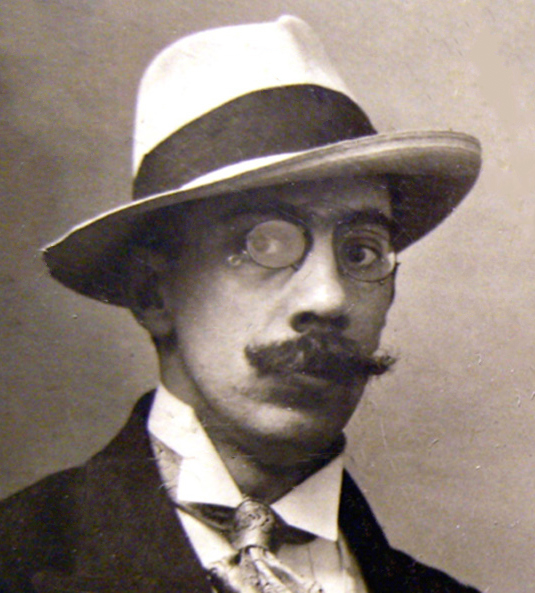

Alexander Belyaev

View on Wikipedia

Alexander Romanovich Belyaev (Russian: Алекса́ндр Рома́нович Беля́ев, [ɐlʲɪkˈsandr rɐˈmanəvʲɪtɕ bʲɪˈlʲæɪf]; 16 March [O.S. 4 March] 1884 – 6 January 1942) was a Soviet Russian writer of science fiction. His works from the 1920s and 1930s made him a highly regarded figure in Russian science fiction, often referred to as "Russia's Jules Verne".[1] Belyaev's best known novels include Professor Dowell's Head, Amphibian Man, Ariel, and The Air Seller.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]

Alexander Belyaev was born in Smolensk in the family of an Orthodox priest. His father, after losing two other children (Alexander's sister Nina died at childhood from sarcoma and his brother Vasiliy, a veterinary student, drowned during a boat trip), wanted him to continue the family tradition and enrolled Alexander into Smolensk seminary. Belyaev, on the other hand, didn't feel particularly religious and even became an atheist in seminary. After graduating he didn't take his vows and enrolled into a law school. While he studied law his father died and he had to support his mother and other family by giving lessons and writing for theater.

After graduating from the school in 1906 Belyaev became a practicing lawyer and made himself a good reputation. In that period his finances markedly improved, and he traveled around the world extensively as a vacation after each successful case. During that time he continued to write, albeit on small scale. Literature, however, proved increasingly appealing to him, and in 1914 he left law to concentrate on his literary pursuits. However, at the same time, at the age of 30, Alexander became ill with tuberculosis.

Treatment was unsuccessful; the infection spread to his spine and resulted in paralysis of the legs. Belyaev suffered constant pain and was paralysed for six years. His wife left him, not wanting to care for the paralyzed. In search for the right treatment he moved to Yalta together with his mother and old nanny. During his convalescence, he read the work of Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, and began to write poetry in his hospital bed.

By 1922 he had overcome the disease and tried to find occupation in Yalta. He served a brief stint as a police inspector, tried other odd jobs such as a librarian, but life remained difficult, and in 1923 he moved to Moscow where he started to practice law again, as a consultant for various Soviet organizations. At the same time Belyaev began his serious literary activity as writer of science fiction novels. In 1925 his first novel, Professor Dowell's Head (Голова Профессора Доуэля) was published. From 1931 he lived in Leningrad with his wife and oldest daughter; his youngest daughter died of meningitis in 1930, aged six. In Leningrad he met H. G. Wells, who visited the USSR in 1934.

In the last years of his life Belyaev lived in the Leningrad suburb of Pushkin (formerly Tsarskoye Selo). At the beginning of the German invasion of the Soviet Union during the Second World War he refused to evacuate because he was recovering after an operation that he had undergone a few months earlier.

Death

[edit]Belyaev died of starvation in the Soviet town of Pushkin in 1942 while it was occupied by the Nazis. The exact location of his grave is unknown. A memorial stone at the Kazanskoe cemetery in the town of Pushkin is placed on the mass grave where his body is assumed to be buried.

His wife and daughter survived and were registered as Volksdeutsche (Belyaev's wife's mother was of Swedish descent). Near the end of the war they were taken away to Poland by the Nazis. Due to this, after the war, Soviets treated them as collaborators: they were exiled to Barnaul (Western Siberia) and lived there for 11 years.[2][3]

Posthumous copyright dispute

[edit]According to the Soviet copyright law in effect until 1964, Belyaev's works entered the public domain 15 years after his death. In the post-Soviet era, Russia's 1993 copyright law granted copyright protection for 50 years after the author's death. With the adoption of Part IV of the Civil Code of Russia in 2004, copyright protection was extended to 70 years after the author's death, and by an additional 4 years for authors who worked or fought during the Great Patriotic War. And a 2006 law stated that the Civil Code's copyright protections described under articles 1281, 1318, 1327, and 1331 do not apply to works whose 50 year p.m.a. copyright term expired before the 1993 law came into force.[4] All of this contributed to confusion about whether or not Belyaev's works are protected by copyright, and for how long.

In 2008, Terra publishing company acquired exclusive rights to print Belyaev's works from his heirs, and proceeded to sue Astrel and AST-Moskva publishing companies (both part of AST) for violating those exclusive rights. The Moscow arbitration court found in favor of Terra, awarding 7.5 billion rubles in damages and barring Astrel from distributing the "illegally published" works.[5] An appellate court found that the awarded damages were calculated unjustifiably and dismissed them.[5] On further appeal, a federal arbitration court found that Belyaev's works entered the public domain on 1 January 1993, and could not enjoy copyright protection at all. In 2010, a Krasnodar cassation panel agreed that Belyaev's works are in the public domain.[6] Finally, in 2011 the High Court of Arbitration of Russia found that Belyaev's works are protected by copyright until 1 January 2017 due to his activity during the Great Patriotic War, and remanded the case to lower courts for retrial.[5] In 2012 the parties have come to a settlement.[7]

Bibliography

[edit]Selected works

[edit]- Professor Dowell's Head (Голова профессора Доуэля, short story — 1924, novel — 1937), New York, Macmillan, 1980. ISBN 0-02-508370-8

- The Ruler of the World (Властелин мира, 1926)

- The Shipwreck Island (ru:Остров погибших кораблей, 1926) Publisher: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012. ISBN 1480000310

- The Amphibian Man (Человек-амфибия, 1928), Moscow, Raduga Publisher, 1986. ISBN 5-05-000659-7

- The Last Man from Atlantis (Последний человек из Атлантиды, 1926)

- Battle in the Ether (Борьба в эфире, 1928; 1st edition named Radiopolis — 1927)

- Eternal Bread (Вечный хлеб, 1928)

- The Man Who Lost His Face (Человек, потерявший лицо, 1929)

- The Air Seller (Продавец воздуха, 1929)

- Underwater Farmers (Подводные земледельцы, 1930)

- Jump into the Void (Прыжок в ничто, 1933)

- The Wonderful Eye (Чудесное око, 1935)

- The Air Vessel (Воздушный корабль, 1935)

- KETs Star (Звезда КЭЦ, 1936) (KETs are the initials of Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky)

- The W Lab (Лаборатория Дубльвэ, 1938)

- The Man Who Found His Face (Человек, нашедший своё лицо, 1940)

- Ariel (Ариэль, 1941)

- Professor Wagner's Inventions series

- Hoity Toity (Хойти-Тойти, 1930)

Anthologies edited

[edit]- A Visitor from Outer Space (2001)

Film adaptations

[edit]- Amphibian Man («Человек-амфибия», 1961)

- The Air Seller (film) («Продавец воздуха» 1967)

- Professor Dowell's Testament («Завещание профессора Доуэля», 1984)

- Island of Lost Ships («Остров погибших кораблей», 1987)

- A Satellite of planet Uranus («Спутник планеты Уран», 1990)

- Ariel (1992 film) («Ариэль», 1992)

- Rains in the Ocean («Дожди в океане», 1994)

- Amphibian Man: The Sea Devil («Человек-амфибия: Морской Дьявол», 2004)

References

[edit]- ^ "Русские писатели и поэты" [Russian writers and poets]. Краткий биографический словарь (in Russian). Moscow. 2000.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Миров, Сергей (28 June 2001). "Материк Погибших Кораблей". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Александр Романович Беляев (1942-1984)". Alexandrbelyaev.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Федеральный закон от 18.12.2006 № 231-ФЗ (in Russian). 2006. Retrieved 4 November 2017 – via WikiSource.

- ^ a b c Шиняева, Наталья (5 October 2011). "Два года войны продлили срок защиты авторского права фантаста Беляева - решение ВАС". Pravo.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "Суд признал "Человека-амфибию" народным достоянием". Lenta.ru (in Russian). 22 July 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ ОПРЕДЕЛЕНИЕ о прекращении производства по делу

External links

[edit] Media related to Alexander Belayev at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alexander Belayev at Wikimedia Commons- Alexander Belyaev at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Alexander Belyaev

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Family Background

Alexander Romanovich Belyaev was born on March 16, 1884, in Smolensk, Russian Empire, into the family of an Orthodox priest, Roman Petrovich Belyaev, and his wife, Nadezhda Vasilyevna (née Chernyakovskaya).[5] The family resided in a modest home on Bolshaya Odigitrievskaya Street (now Dokuchaeva Street), where Roman Petrovich served as rector of the Odigitrievskaya Church, providing a stable but limited income reflective of clerical life in provincial Russia.[5] Belyaev was the middle child, with an older brother, Vasily Romanovich, who drowned in the Dnieper River during a boating accident in the summer of 1900, and a younger sister, Nina Romanovna, who died in childhood from liver sarcoma.[5] As the sole surviving sibling into adulthood, Belyaev grew up in a deeply religious environment shaped by his father's vocation, which emphasized moral and spiritual values that permeated the household.[5] This upbringing, intended to prepare him for a clerical career, instilled early exposure to ethical storytelling through his father's biblical narratives and sermons, fostering a foundation for the moral dilemmas explored in his later science fiction works.[5] The death of Roman Petrovich on March 27, 1905, from illness plunged the family into financial hardship, as the priest's modest salary ceased without pension support.[5] Nadezhda Vasilyevna relied on her son for support, compelling the young Belyaev to take on tutoring and clerical jobs while pursuing his own path away from the church.[5] Amid these challenges, Belyaev's childhood in Smolensk included avid reading at local libraries, where he discovered adventure literature, particularly the scientific romances of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, sparking his imagination and interest in speculative ideas.[5] He often reenacted scenes from these books with his brother, blending familial storytelling traditions with emerging literary passions.[5] Early health issues, such as severe eczema, also marked this period, though they were managed within the family's constrained resources.[5]Education and Early Influences

Belyaev entered the Smolensk Spiritual School in 1891 at the age of seven, as his father, an Orthodox priest, intended for him to pursue a clerical career. He excelled academically and transferred to the Smolensk Theological Seminary in 1895, completing his studies there in 1901 with top honors. Despite the rigorous religious curriculum, Belyaev emerged as a committed atheist, having secretly explored secular ideas that conflicted with seminary teachings.[6] Throughout his seminary years, Belyaev pursued extensive self-education outside the formal program, immersing himself in natural sciences, philosophy, and literature. He avidly read works by Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, whose imaginative explorations of technology and human potential profoundly shaped his fascination with scientific progress and the unknown. Russian classics, particularly Nikolai Gogol's satirical and fantastical narratives, further influenced his early worldview, blending realism with the supernatural. These readings fueled his intellectual rebellion against dogmatic constraints and sparked a lifelong passion for speculative ideas.[7] Defying his family's expectations, Belyaev enrolled in the Demidov Law Lyceum in Yaroslavl in 1902 to study law. Financial hardships and emerging health concerns, compounded by the disruptions of the 1905 revolution, forced him to interrupt his studies, during which he supported himself by working as an actor and musician in local theaters. He resumed his legal education as an external student and graduated in 1909, qualifying him to practice as a private attorney.[8]Professional Career

Legal Practice

After graduating from the Demidov Lyceum of Law in Yaroslavl in 1909, Alexander Belyaev passed the necessary examinations and qualified as an assistant sworn attorney the following year, beginning his legal practice in Smolensk.[5] By 1910, he had established himself in the local courts, where he focused primarily on criminal and civil cases.[5] His work exposed him to the harsh realities of pre-revolutionary Russia, including widespread poverty, exploitative labor conditions, and systemic inequalities that disproportionately affected the working class.[5] Among his notable cases in the 1910s were defenses of workers involved in labor disputes, such as strikes and unfair dismissal claims against factory owners, where Belyaev argued for better wages and working conditions amid growing industrial tensions.[5] One early success came in 1909 when he secured the release of a Socialist Revolutionary party leader accused of political agitation, demonstrating his willingness to take on high-risk cases that challenged authorities.[5] These experiences profoundly shaped his worldview, later influencing the social critiques embedded in his science fiction, where themes of injustice, human exploitation, and the need for societal reform recur as undercurrents to technological narratives. In 1911, he also won a lucrative civil suit for a lumber industrialist, which provided financial relief and highlighted the disparities between elite and proletarian clients.[5] In 1915, due to health issues, Belyaev moved to Yalta, where he worked as a tutor and inspector of criminal investigation while continuing some legal activities.[5] By 1923, he had moved to Moscow amid post-revolutionary changes, where he balanced legal consultations with emerging journalistic pursuits, though his primary income still derived from law.[5] The financial stability from his legal work afforded him the leisure to devour scientific journals on topics like biology and physics, fostering the interdisciplinary knowledge that would fuel his literary imagination.[5]Transition to Journalism

Due to deteriorating health from pleurisy and tuberculosis, which left him paralyzed and bedridden from 1917 to 1921, Belyaev abandoned his legal practice around 1917 and began transitioning to writing as a means of livelihood.[9][10] He started his journalistic career as a feuilletonist, contributing light satirical pieces to newspapers, where his witty commentary on contemporary events helped establish his voice in popular media.[10] Between 1917 and 1920, Belyaev continued writing on legal topics, including articles advocating for criminal justice reforms in specialized journals, drawing on his prior experience as a lawyer to critique systemic issues in the post-revolutionary legal landscape.[9] By the early 1920s, his focus shifted toward science popularization; he published articles exploring emerging fields like aviation and biology, which introduced speculative elements that later influenced his science fiction narratives.[10] This freelance work was supported by his marriage in 1922, which provided emotional and practical stability during his recovery and career pivot.[4] Early in his journalistic endeavors, Belyaev blended factual reporting with imaginative commentary on scientific advancements.[9]Literary Works

Debut and Major Novels

Belyaev entered the realm of science fiction with his debut novel, Professor Dowell's Head (Golova professora Douelya), serialized in the magazine Vsemirnyy sledopyt from June to July 1925 and published in book form in 1926.[9] The narrative revolves around an unethical surgeon, Professor Kern, who decapitates the renowned physiologist Professor Dowell and sustains his severed head alive in a nutrient solution for experimental purposes, leading to the head's tormented existence and eventual revenge through a student's intervention.[9] This work marked Belyaev's innovative exploration of organ transplantation and the ethical dilemmas of scientific ambition, influenced by his personal struggles with paralysis and contemporary medical debates.[9] Belyaev's major novels quickly established his reputation, often serialized in the popular Soviet magazine Vokrug sveta (Around the World), which popularized scientific adventures during the 1920s and 1930s.[9] His breakthrough success came with The Amphibian Man (Chelovek-amfibiia, 1928), serialized in 13 issues of Vokrug sveta, where a reclusive biologist surgically implants shark gills into his son Ichthyander, creating a hybrid capable of underwater life but doomed to alienation from land-based society and pursued by exploiters.[9] The novel innovatively probes genetic engineering's moral boundaries and the human cost of scientific experimentation, blending romance, adventure, and cautionary ethics in a South American coastal setting.[9] In The Seller of Air (Prodavets vozdukha, 1929), also serialized in Vokrug sveta, Belyaev envisions a near-future crisis where industrial pollution depletes breathable air, allowing a ruthless English industrialist, Mr. Bailey, to monopolize synthetic oxygen production for profit.[11] The plot follows Soviet meteorologist Georgy Klimenko and his companions as they investigate atmospheric anomalies in Siberia, exposing corporate greed and averting ecological catastrophe through international cooperation.[4] This aviation-tinged thriller introduced prescient themes of environmental ethics and resource exploitation, reflecting Soviet optimism in science's redemptive power.[4] Belyaev's output continued with equally ambitious works, such as The Master of the World (Vlastelin mira, 1929), in which a biophysicist harnesses telepathic rays to dominate global leaders and enforce peace, only for his hubris to unravel in a tale of mind control's perils.[9] The Last Man from Atlantis (Posledniy chelovek iz Atlantidy, 1927) depicts a wealthy financier's expedition to rediscover the sunken continent, encountering its sole immortal survivor and unraveling ancient evolutionary secrets amid underwater perils.[12] By 1936, The Star KETS (Zvezda KÉTs) advanced Belyaev's space-focused innovations, chronicling a multi-generational interstellar voyage aboard a rocket ship powered by Tsiolkovsky-inspired propulsion, emphasizing cosmic exploration's triumphs and human resilience.[4] These novels, grounded in rigorous consultation with contemporary scientific literature and experts, showcased Belyaev's commitment to plausible futurism amid Soviet enthusiasm for technological progress.[13] By 1942, he had authored 17 novels, solidifying his role as a foundational figure in Russian science fiction through serialized publications that captivated millions.[14]Short Stories and Themes

Belyaev's short fiction represents a significant portion of his output, with numerous stories published alongside his novels during the 1920s and 1930s, often exploring the frontiers of science in compact, adventure-driven narratives. Collections of these tales were published during the 1930s, emphasizing inventive plots centered on technological innovation and human potential.[15] His prose style was accessible, blending speculative elements with fast-paced storytelling to make complex scientific ideas engaging for a broad Soviet readership.[16] Recurring themes in Belyaev's short stories include optimistic futurism, portraying science as a tool for societal progress and human enhancement under socialist principles. For instance, narratives like "Hoity-Toity (Professor Wagner’s Invention)" depict inventors harnessing technology to overcome limitations, reflecting an enthusiasm for a future where scientific advances benefit humanity collectively.[16] This optimism evolved in the 1930s toward greater ideological alignment with Soviet values, as seen in stories that integrated anti-fascist motifs and critiques of capitalist exploitation of science.[17] Ethical dilemmas in science form another core theme, particularly the moral boundaries of experimentation and its impact on human identity. Belyaev frequently examined issues like eugenics and immortality through scenarios involving radical interventions, such as head transplants and reanimation, which question the ethics of altering life itself—as illustrated in early works that prefigure his novel Professor Dowell's Head.[16] These stories highlight tensions between progress and humanity, warning of the dangers of unchecked ambition while ultimately affirming ethical science in service of the collective good.[18] Belyaev's short fiction influenced subsequent Soviet science fiction writers, including Ivan Yefremov, by establishing a model of adventure-infused speculation that balanced wonder with ideological purpose, paving the way for later explorations of utopian futures.[19]Personal Challenges

Health Struggles

Belyaev's health deteriorated significantly in 1915 when, at the age of 31, he contracted tuberculosis that spread to his spine, resulting in paralysis of his lower body and confining him to bed for over three years. This condition, known as Pott's disease, severely limited his mobility and marked the beginning of lifelong physical challenges.[20][4] To combat the infection, Belyaev underwent several surgeries in Moscow and spent time in sanatoriums in Crimea, where the climate was believed to aid recovery from tuberculosis. By 1922, after prolonged treatment including the use of a celluloid corset for support, he partially regained the ability to walk, though he remained dependent on assistive devices and experienced chronic pain throughout his life. These interventions allowed him to resume some professional activities, but the paralysis persisted in varying degrees into the 1920s, often requiring wheelchair use.[4] The impact on his career was profound; during his bedridden years, Belyaev turned to reading extensively on science and medicine, which inspired his transition to writing science fiction exploring themes of human endurance and medical innovation. In the 1930s, seeking relief from his ongoing respiratory and spinal issues, he relocated to Pushkin, a suburb of Leningrad with a milder climate, where he continued his literary work despite increasing frailty. This period of isolation, while psychologically taxing, deepened his fascination with resilience against bodily limitations, influencing works that delved into human augmentation and recovery.[20]Family Life

Belyaev was married three times. His first marriage, around 1908 to Anna Ivanovna Stankevich, ended early. His second marriage, from 1913 to 1915 to Vera Bylinskaya, ended when she left him following the onset of his spinal tuberculosis. In 1921, he married for the third time to Margarita Konstantinovna Belyaeva (née Magnushevskaya, 1895–1982), his former nurse, a union that lasted until his death in 1942; she served as his devoted partner and practical assistant, typing his manuscripts by hand due to his physical disabilities from chronic illness.[21] The couple had two daughters: Ludmila (c. 1924–1930), who died of meningitis at age six, and Svetlana Alexandrovna (born July 19, 1929 – died June 8, 2017), who survived into adulthood and later became involved in preserving and managing her father's literary estate.[22][23] Their family life centered in Leningrad from 1931 onward, with a later move to nearby Pushkin in 1934, where the household formed an intellectual hub attracting scientists and like-minded professionals whose conversations on emerging technologies influenced Belyaev's speculative narratives. Margarita shouldered the domestic responsibilities, maintaining stability amid Belyaev's health dependencies that limited his mobility.[9] After the 1917 Revolution, the family navigated the challenges of Soviet transformation, adapting to ideological shifts and economic hardships through relocations tied to Belyaev's evolving career, from legal consulting in Moscow to establishing a writing base in Leningrad.[24]World War II and Death

Siege of Leningrad

When the German invasion of the Soviet Union began on June 22, 1941, Alexander Belyaev, already debilitated by pre-war health issues including paralysis resulting from a severe spinal operation, refused opportunities to evacuate from his home in Pushkin, a suburb of Leningrad, choosing instead to remain with his wife, Margarita Konstantinovna Magnuchevskaya, and their 12-year-old daughter, Svetlana.[25] By September 1941, as Nazi forces advanced, Pushkin fell under German occupation, enveloping the area in the broader Siege of Leningrad that would last until January 1944.[25] The Belyaev family faced extreme hardships during the early months of the blockade, subsisting on starvation-level rations that dwindled to mere crumbs of bread and occasional scraps, compounded by relentless aerial bombings and artillery shelling that shattered the suburb's fragile calm.[25] Belyaev's worsening paralysis rendered later evacuation plans unfeasible, stranding the family in their isolated wooden house amid the chaos of occupation, where basic survival became an all-consuming struggle against hunger and cold.[25] Despite these dire conditions and acute shortages of food, fuel, and writing materials, Belyaev persisted in his creative endeavors, managing to outline an unfinished science fiction novel titled The Man Who Didn't Sleep, a work exploring themes of human endurance and scientific innovation that reflected his own unyielding spirit.[25] His wife played a crucial role in their survival efforts, venturing out to forage for edible plants, roots, and any available scraps in the snow-covered fields and forests surrounding Pushkin, often under threat from patrols and the elements.[25] Cut off from Leningrad's literary circles by the blockade's tightening grip, Belyaev and his family endured profound isolation, with no contact from fellow writers or publishers, as the siege severed communication lines and diverted all resources to military defense.[25] This period marked a stark halt to Belyaev's once-prolific output, as physical frailty and the relentless demands of survival overshadowed his intellectual pursuits.[25]Final Days and Burial

In the final months of his life, Alexander Belyaev endured severe deprivation during the German occupation of Pushkin amid the Siege of Leningrad, where food shortages and harsh winter conditions exacerbated his longstanding health issues. By late December 1941, he was bedridden and suffering from extreme malnutrition, leading to his death in late December 1941 or early January 1942, at the age of 57.[26] He died of starvation amid the hardships of the blockade.[26] Due to the chaos of the occupation and ongoing artillery fire, no formal funeral could be held; Belyaev's body was temporarily kept in a neighboring apartment before burial. His wife, Margarita Belyaeva, arranged for a hasty interment in a shallow grave within a common ditch at the Kazan Cemetery in Pushkin, as individual graves were not feasible under the circumstances. According to accounts, a German officer and four soldiers carried and buried his body. The exact location remains unknown, and a stele was placed at the presumed site on November 1, 1968.[26][25] Margarita survived the ordeal, including deportation to Germany for forced labor alongside Svetlana, and played a crucial role in safeguarding Belyaev's unpublished manuscripts, which she preserved through exile and repression upon their return to the Soviet Union.[26]Posthumous Legacy

Recognition and Influence

Following Belyaev's death in 1942 during the Siege of Leningrad, his works faced temporary suppression amid the Stalinist crackdown on speculative fiction, but they experienced a significant revival during the Khrushchev Thaw. Reprints began appearing in the mid-1950s, with key novels like The Amphibian Man reissued in 1956 and becoming nationwide bestsellers, reflecting renewed official support for science fiction as a genre promoting technological progress. By the 1960s, full collected editions of his oeuvre were published, solidifying his status as a foundational figure in Soviet literature and introducing his stories to a new generation of readers eager for optimistic visions of science amid the Space Race era.[5] Belyaev is widely regarded as the pioneer of Soviet science fiction, often called the "Russian Jules Verne" for blending adventure with scientific themes that emphasized human potential and ethical innovation. His influence extended to later authors, including the Strugatsky brothers, who acknowledged him as the "father of Soviet science fiction" for establishing a tradition of accessible, idea-driven narratives that shaped the genre's development in the USSR. Themes of scientific optimism in works like The Air Seller resonated during the 1950s-1970s, aligning with Soviet propaganda on space exploration and technological triumphs, and inspiring a wave of writers who built on his model of speculative storytelling to explore societal futures.[9][27][28] Although Belyaev received no major awards during his lifetime due to his health struggles and the pre-war literary climate, posthumous honors recognized his contributions, including honorary citizenship of Smolensk—his birthplace—awarded in 2014 by the city council. Memorials and exhibits at the Smolensk Historical Museum highlight his legacy, while in Pushkin (formerly Tsarskoye Selo), where he spent his final years, local commemorations mark his residence and death. His global reach expanded dramatically after the 1950s, with translations into dozens of languages by the 1980s, including major editions in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian, and many others, introducing his bio-ethical dilemmas and utopian visions to international audiences.[29][30][31]Copyright Dispute

During the Soviet era, Alexander Belyaev's works were considered state property, with copyrights managed collectively through state publishing houses and entering the public domain after a limited term under Soviet legislation, which provided protection for the author's life plus 15 years until reforms in 1964 extended it further.[32] Following the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, Belyaev's daughter, Svetlana Alexandrovna Belyaeva, asserted claims to the literary rights as his heir, leveraging Russia's accession to the Berne Convention in 1995 and the 1993 copyright law, which retroactively granted protections of up to 50 years post-mortem (later extended to 70 years in 2008).[33] This transition reflected broader post-Soviet efforts to align with international intellectual property standards, allowing heirs to reclaim rights from what had been treated as public domain under communist-era rules.[34] In 2001, Svetlana Belyaeva sold exclusive publishing rights to her father's works to the Russian publisher Izdatelstvo "Terra," enabling it to issue multiple editions, including over 630 gift sets comprising six volumes each.[35] This contract sparked legal conflicts in the 2000s when competing publishers, such as Izdatelstvo "Astrel," released unauthorized editions, arguing that the copyrights had expired decades earlier under Soviet terms—specifically, by 1993 at the latest, given Belyaev's death in 1942.[33] The disputes centered on the applicability of the 70-year post-mortem term introduced in 1993 (amended in 2004), with "Terra" contending for an additional four-year extension for authors affected by World War II, pushing protection until 2016–2017; "Astrel" countered that pre-1993 expirations rendered the works free for use.[32] Key lawsuits unfolded in Moscow Arbitration Court starting around 2008, with "Terra" suing "Astrel" for infringement over publications exceeding 25,000 copies in recent years.[35] In a landmark 2011 ruling, the Higher Arbitration Court (VAS) sided with the heirs' position, confirming that Belyaev's works were not in the public domain and affirming the WWII extension, setting a precedent for other Soviet-era authors like Arkady Gaidar and Yevgeny Petrov; this decision mandated heir approval for publications and recalculated compensation in ongoing cases.[32] Initial court awards favored "Terra" with 7.5 billion rubles in damages—equivalent to twice the claimed revenue from the infringing editions—but appeals overturned these, leading to a 2012 pause for settlement negotiations between the parties.[34] These partial victories for the family highlighted the challenges of post-Soviet intellectual property enforcement, though copyrights ultimately expired around 2016, placing Belyaev's oeuvre in the public domain thereafter.[36]Bibliography

Key Novels

Alexander Belyaev's key novels, spanning from 1925 to the early 1940s, established him as a pioneering figure in Soviet science fiction, blending adventure, ethical dilemmas, and speculative technology. His works were often serialized in journals before book publication, reflecting the era's literary practices. Below is a chronological overview of his primary novels, including original Russian titles, first publication details, and genres.- Голова профессора Доуэля (The Head of Professor Dowell), 1925: First serialized in the journal Vsemirnaya Illyustrirovannaya Novost and published as a book by Gosizdat; medical horror/science fiction exploring unethical experiments on human preservation.[37]

- Остров погибших кораблей (Island of the Lost Ships), 1926–1927: Serialized in Vsemirny Sledopyt (issues 3–6); adventure/science fiction depicting a mysterious island with ancient civilizations. (Note: Using for publication fact only, as primary source via journal archive reference)

- Властелин мира (Master of the World), 1926: Serialized in Gudok; science fiction depicting global domination through advanced weaponry.

- Человек-амфибия (The Amphibian Man), 1928: Published by Gosizdat; bioethics/science fiction examining human-animal hybridization and societal exploitation.[38]

- Продавец воздуха (The Air Seller), 1929: Serialized in Vokrug Sveta (issues 4–13); dystopian/science fiction critiquing resource monopolization in a future society.

- Человек, потерявший лицо (The Man Who Lost His Face), 1929: Published by Zemlya i Fabrika; science fiction on identity and plastic surgery innovations.

- Прыжок в ничто (Leap into Nothing), 1933: Published by OGIz-Molodaya Gvardiya; science fiction involving experimental space travel and psychological extremes.

- Чудесное око (The Marvelous Eye), 1935: Published by Detgiz; science fiction focusing on optical enhancements and perception alteration.[39]

- Звезда КЭЦ (Star KEC), 1936: Serialized in Tekhnika – Molodezhi; space exploration/science fiction involving interstellar communication. (Note: Originally planned as "Vtoraya Luna" / The Second Moon.)

- Под небом Арктики (Under the Arctic Sky), 1938: Published by Molodaya Gvardiya; adventure/science fiction set amid polar expeditions and survival.[39]

- Ариэль (Ariel), 1941: Published by Sovetsky Pisatel; science fiction on levitation and human potential.[40]

- Пещера дракона (Cave of the Dragon), ca. 1939–1940 (unfinished): Planned as a children's fantasy-adventure novel, with fragments outlining themes of discovery and future transport; never fully published during Belyaev's lifetime.[41]