Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Space Race

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Spaceflight |

|---|

|

|

|

The Space Race (Russian: космическая гонка, romanized: kosmicheskaya gonka, IPA: [kɐsˈmʲitɕɪskəjə ˈɡonkə]) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the two nations following World War II and the onset of the Cold War. The technological advantage demonstrated by spaceflight achievement was seen as necessary for national security, particularly in regard to intercontinental ballistic missile and satellite reconnaissance capability, but also became part of the cultural symbolism and ideology of the time. The Space Race brought pioneering launches of artificial satellites, robotic landers to the Moon, Venus, and Mars, and human spaceflight in low Earth orbit and ultimately to the Moon.[1][2][3][4]

Public interest in space travel originated in the 1951 publication of a Soviet youth magazine and was promptly picked up by US magazines.[5] The competition began on July 29, 1955, when the United States announced its intent to launch artificial satellites for the International Geophysical Year. Five days later, the Soviet Union responded by declaring they would also launch a satellite "in the near future". The launching of satellites was enabled by developments in ballistic missile capabilities since the end of World War II.[6] The competition gained Western public attention with the "Sputnik crisis", when the USSR achieved the first successful satellite launch, Sputnik 1, on October 4, 1957. It gained momentum when the USSR sent the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space with the orbital flight of Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961. These were followed by a string of other firsts achieved by the Soviets over the next few years.[7][8][9]

Gagarin's flight led US president John F. Kennedy to raise the stakes on May 25, 1961, by asking the US Congress to commit to the goal of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth" before the end of the decade.[10][2] Both countries began developing super heavy-lift launch vehicles, with the US successfully deploying the Saturn V, which was large enough to send a three-person orbiter and two-person lander to the Moon. Kennedy's Moon landing goal was achieved in July 1969, with the flight of Apollo 11.[11][12][13] The USSR continued to pursue crewed lunar programs to launch and land on the Moon before the US with its N1 rocket but did not succeed, and eventually canceled it to concentrate on Salyut, the first space station program, and the first landings on Venus and on Mars. Meanwhile, the US landed five more Apollo crews on the Moon,[14] and continued exploration of other extraterrestrial bodies robotically.

A period of détente followed with the April 1972 agreement on a cooperative Apollo–Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), resulting in the July 1975 rendezvous in Earth orbit of a US astronaut crew with a Soviet cosmonaut crew and joint development of an international docking standard APAS-75. Being considered as the final act of the Space Race by many observers,[15] the competition was however only gradually replaced with cooperation.[16] The collapse of the Soviet Union eventually allowed the US and the newly reconstituted Russian Federation to end their Cold War competition also in space, by agreeing in 1993 on the Shuttle–Mir and International Space Station programs.[17][18]

Origins

[edit]

Although Germans, Americans and Soviets experimented with small liquid-fuel rockets before World War II, launching satellites and humans into space required the development of larger ballistic missiles such as Wernher von Braun's Aggregat-4 (A-4), which became known as the Vergeltungswaffe 2 (V-2) developed by Nazi Germany to bomb the Allies in the war.[19] After the war, both the US and USSR acquired custody of German rocket development assets which they used to leverage the development of their own missiles.

Public interest in space flight was first aroused in October 1951 when the Soviet rocketry engineer Mikhail Tikhonravov published "Flight to the Moon" in the newspaper Pionerskaya pravda for young readers. He described a two-person interplanetary spaceship of the future and the industrial and technological processes required to create it. He ended the short article with a clear forecast of the future: "We do not have long to wait. We can assume that the bold dream of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky will be realized within the next 10 to 15 years."[20] From March 1952 to April 1954, the US Collier's magazine reacted with a series of seven articles Man Will Conquer Space Soon! detailing Wernher von Braun's plans for crewed spaceflight. In March 1955, Disneyland's animated episode "Man in Space" which was broadcast on US television with an audience of about 40 million people, eventually fired the public enthusiasm for space travel and raised government interest, both in the US and USSR.

Missile race

[edit]Soon after the end of World War II, the two former allies became engaged in a state of political conflict and military tension known as the Cold War (1947–1991), which polarized Europe between the Soviet Union's satellite states (often referred to as the Eastern Bloc) and the states of the Western world allied with the U.S.[21]

In August 1949, the Soviet Union became the second nuclear power after the United States with the successful RDS-1 nuclear weapon test. In October 1957, the Soviet Union conducted the world's first successful test of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), this was the R-7 Semyorka (also known as SS-6 by NATO) and was seen as capable of striking U.S. territory with a nuclear payload.[22][23] Fears in the US due to this perceived threat became known as the 'missile gap'. The first American ICBM, the Atlas missile, was tested in late 1958.[22][24]

ICBMs presented the ability to strike targets on the other side of the globe in a very short amount of time and in a manner which was impervious to air interception such as bombers might have been. The value which ICBMs presented in a nuclear standoff were very substantial, and this fact greatly accelerated efforts to develop rocket and rocket interception technology.[25]

Soviet rocket development

[edit]

The first Soviet development of artillery rockets was in 1921 when the Soviet military sanctioned the Gas Dynamics Laboratory, a small research laboratory to explore solid-fuel rockets, led by Nikolai Tikhomirov, who had begun studying solid and liquid-fueled rockets in 1894, and obtained a patent in 1915 for "self-propelled aerial and water-surface mines.[26][27] The first test-firing of a solid fuel rocket was carried out in 1928.[28]

Further development was carried out in the 1930s by the Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (GIRD), where Soviet rocket pioneers Sergey Korolev, Friedrich Zander, Mikhail Tikhonravov and Leonid Dushkin[29] launched GIRD-X, the first Soviet liquid-fueled rocket in 1933.[30] In 1933 the two design bureaus were combined into the Reactive Scientific Research Institute[31] and produced the RP-318, the USSR's first rocket-powered aircraft and the RS-82 and RS-132 missiles,[32] which became the basis for the Katyusha multiple rocket launcher,[33][34] During the 1930s Soviet rocket technology was comparable to Germany's,[35] but Joseph Stalin's Great Purge from 1936 to 1938 severely damaged its progress.

In 1945 the Soviets captured several key Nazi German A-4 (V-2) rocket production facilities, and also gained the services of some German scientists and engineers related to the project. A-4s were assembled and studied and the experience derived from assembling and launching A4 rockets was directly applied to the Soviet copy, called the R-1,[36][37] with NII-88 chief designer Sergei Korolev overseeing the R-1's development.,[38] The R-1 entered into service in the Soviet Army on 28 November 1950.[39][40] By the latter half of 1946, Korolev and rocket engineer Valentin Glushko had, with extensive input from German engineers, outlined a successor to the R-1, the R-2 with an extended frame and a new engine designed by Glushko,[41] which entered service in November, 1951, with a range of 600 kilometres (370 mi), twice that of the R-1.[42] This was followed in 1951 with the development of the R-5 Pobeda, the Soviet Union's first real strategic missile, with a range of 1,200 km (750 mi) and capable of carrying a 1 megaton (mt) thermonuclear warhead. The R-5 entered service in 1955.[43] Scientific versions of the R-1, R-2 and R-5 undertook various experiments between 1949 and 1958, including flights with space dogs.[44]: 21–23

Design work began in 1953 on the R-7 Semyorka with the requirement for a missile with a launch mass of 170 to 200 tons, range of 8,500 km and carrying a 3,000 kg (6,600 lb) nuclear warhead, powerful enough to launch a nuclear warhead against the United States. In late 1953 the warhead's mass was increased to 5.5 to 6 tons to accommodate the then planned theromonuclear bomb.[45][46] The R-7 was designed in a two-stage configuration, with four boosters that would jettison when empty.[47] On the 21 August 1957 the R-7 flew 6,000 km (3,700 mi), and became the worlds's first intercontinental ballistic missile.[48][46] Two months later the R-7 launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, into orbit, and became the basis for the R-7 family which includes Sputnik, Luna, Molniya, Vostok, and Voskhod space launchers, as well as later Soyuz variants. Several versions are still in use and it has become the world's most reliable space launcher.[49][50]

American rocket development

[edit]

Although American rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard developed, patented, and flew small liquid-propellant rockets as early as 1914, the United States was the only one of the three major allied World War II powers to not have its own rocket program, until Von Braun and his engineers were expatriated from Nazi Germany in 1945. The US acquired a large number of V-2 rockets and recruited von Braun and most of his engineering team in Operation Paperclip.[51] The team was sent to the Army's White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico, in 1945.[52] They set about assembling the captured V-2s and began a program of launching them and instructing American engineers in their operation.[53] These tests led to the first photos of Earth from space, and the first two-stage rocket, the WAC Corporal-V-2 combination, in 1949.[53] The German rocket team was moved from Fort Bliss to the Army's new Redstone Arsenal, located in Huntsville, Alabama, in 1950.[54] From here, von Braun and his team developed the Army's first operational medium-range ballistic missile, the Redstone rocket, derivatives of which launched both America's first satellite, and the first piloted Mercury space missions.[54] It became the basis for both the Jupiter and Saturn family of rockets.[54]

Each of the United States armed services had its own ICBM development program. The Air Force began ICBM research in 1945 with the MX-774.[55] In 1950, von Braun began testing the Air Force PGM-11 Redstone rocket family at Cape Canaveral.[56] By 1957, a descendant of the Air Force MX-774 received top-priority funding.[55] and evolved into the Atlas-A, the first successful American ICBM.[55] The Atlas made use of a thin stainless steel fuel tank which relied on the internal pressure of the tank for structural integrity, this allowed an overall lighter weight design.[57] WD-40 was developed to prevent rust on the Atlas rockets so that rust protecting paint could be avoided, to further reduce weight.[58][59]

A later variant of the Atlas, the Atlas-D, served as a nuclear ICBM and as the orbital launch vehicle for Project Mercury and the remote-controlled Agena Target Vehicle used in Project Gemini.[55]

ICBM capability, satellites, lunar probes (1955–1960)

[edit]The period from 1955 to 1960 saw the first artificial satellites put into earth orbit by both the USSR and the US, the first animals sent into orbit, and the first robotic probes to impact and flyby the Moon by the Soviets.

Artificial satellite development

[edit]In 1955, with both the United States and the Soviet Union building ballistic missiles that could be used to launch objects into space, the stage was set for nationalistic competition.[6] On July 29, 1955, James C. Hagerty, President Dwight D. Eisenhower's press secretary, announced that the United States intended to launch "small Earth circling satellites" between July 1, 1957, and December 31, 1958, as part of the US contribution to the International Geophysical Year (IGY).[6] On August 2, at the Sixth Congress of the International Astronautical Federation in Copenhagen, scientist Leonid I. Sedov told international reporters at the Soviet embassy of his country's intention to launch a satellite as well, in the "near future".[6]

Soviet secrecy and obfuscation

[edit]On August 30, 1955, Sergei Korolev succeeded in convincing the Soviet Academy of Sciences to establish a commission dedicated to achieving the goal of launching a satellite into Earth orbit before the United States,[6] this can be viewed as the de facto start date of the space race. The Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union began a policy of treating development of its space program as top-secret. When the Sputnik project was first approved, one of the immediate courses of action the Politburo took was to consider what to announce to the world regarding their event. The Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) established precedents for all official announcements on the Soviet space program. The information eventually released did not offer details on who built and launched the satellite or why it was launched.[60]

The Soviet space program's use of secrecy served as both a tool to prevent the leaking of classified information between countries, and to avoid revealing specifics to the Soviet populace in regards to their short and long term goals; the program's nature embodied ambiguous messages concerning its goals, successes, and values. Launches were not announced until they took place, cosmonaut names were not released until they flew, and outside observers did not know the size or shape of their rockets or cabins of most of their spaceships, except for the first Sputniks, lunar probes, and Venus probe.[61]

The Soviet military maintained control over the space program; Korolev's OKB-1 design bureau was subordinated under the Ministry of General Machine Building,[60] tasked with the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles, and continued to give its assets random identifiers into the 1960s.[60] Information about failures was systematically withheld, historian James Andrews notes that Soviet media coverage of the space program, particularly human space missions, rarely reported any failures or difficulties, creating the impression of a flawless operation:

"With almost no exceptions, coverage of Soviet space exploits, especially in the case of human space missions, omitted reports of failure or trouble".[60]

Dominic Phelan noted in the book Cold War Space Sleuths (Springer-Praxis 2013): "The USSR was famously described by Winston Churchill as 'a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma' and nothing signified this more than the search for the truth behind its space program during the Cold War. Although the Space Race was literally played out above our heads, it was often obscured by a figurative 'space curtain' that took much effort to see through".[61]

US concerns and strategy

[edit]Initially, President Eisenhower was worried that a satellite passing above a nation at over 100 kilometers (62 mi) might be seen as violating that nation's airspace.[62] He was concerned that the Soviet Union would accuse the Americans of an illegal overflight, thereby scoring a propaganda victory at his expense.[63] Eisenhower and his advisors were of the opinion that a nation's airspace sovereignty did not extend past the Kármán line, and they used the 1957–58 International Geophysical Year launches to establish this principle in international law.[62] Eisenhower also feared that he might cause an international incident and be called a "warmonger" if he were to use military missiles as launchers. Therefore, he selected the untried Naval Research Laboratory's Vanguard rocket, which was a research-only rocket.[64] This meant that von Braun's team was not allowed to put a satellite into orbit with their Jupiter-C rocket, because of its intended use as a future military vehicle.[64] On September 20, 1956, von Braun and his team did launch a Jupiter-C that was capable of putting a satellite into orbit, but the launch was used only as a suborbital test of reentry vehicle technology.[64]

Sputnik

[edit]

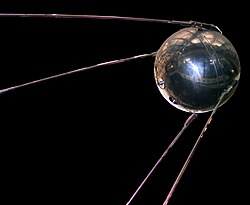

Korolev received word about von Braun's 1956 Jupiter-C test and, mistakenly thinking it was a satellite mission that failed, expedited plans to get his own satellite in orbit. Since the R-7 was substantially more powerful than any of the US launch vehicles, he made sure to take full advantage of this capability by designing Object D as his primary satellite.[65] It was given the designation 'D', to distinguish it from other R-7 payload designations 'A', 'B', 'V', and 'G' which were nuclear weapon payloads.[66] Object D dwarfed the proposed US satellites, having a weight of 1,400 kilograms (3,100 lb), of which 300 kilograms (660 lb) would be composed of scientific instruments that would photograph the Earth, take readings on radiation levels, and check on the planet's magnetic field.[66] However, things were not going along well with the design and manufacturing of the satellite, so in February 1957, Korolev sought and received permission from the Council of Ministers to build a Prosteishy Sputnik (PS-1), or simple satellite.[65] The council also decreed that Object D be postponed until April 1958.[67] The new Sputnik was a metallic sphere that would be a much lighter craft, weighing 83.8 kilograms (185 lb) and having a 58-centimeter (23 in) diameter.[68] The satellite would not contain the complex instrumentation that Object D had, but had two radio transmitters operating on different short wave radio frequencies, the ability to detect if a meteoroid were to penetrate its pressure hull, and the ability to detect the density of the Earth's thermosphere.[69]

Korolev was buoyed by the first successful launches of the R-7 rocket in August and September, which paved the way for the launch of Sputnik.[70] Word came that the US was planning to announce a major breakthrough at an International Geophysical Year conference at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington D.C., with a paper titled "Satellite Over the Planet", on October 6, 1957.[71] Korolev anticipated that von Braun might launch a Jupiter-C with a satellite payload on or around October 4 or 5, in conjunction with the paper.[71] He hastened the launch, moving it to October 4.[71] The launch vehicle for PS-1 was a modified R-7 – vehicle 8K71PS number M1-PS – without much of the test equipment and radio gear that was present in the previous launches.[70] It arrived at the Soviet missile base Tyura-Tam in September and was prepared for its mission at launch site number one.[70]

The first launch took place on Friday, October 4, 1957, at exactly 10:28:34 pm Moscow time, with the R-7 and the now named Sputnik 1 satellite lifting off the launch pad and placing the artificial "moon" into an orbit a few minutes later.[72] This "fellow traveler", as the name is translated in English, was a small, beeping ball, less than two feet in diameter and weighing less than 200 pounds. But the celebrations were muted at the launch control center until the down-range far east tracking station at Kamchatka received the first distinctive beep ... beep ... beep sounds from Sputnik 1's radio transmitters, indicating that it was on its way to completing its first orbit.[72] About 95 minutes after launch, the satellite flew over its launch site, and its radio signals were picked up by the engineers and military personnel at Tyura-Tam: that's when Korolev and his team celebrated the first successful artificial satellite placed into Earth-orbit.[73]

The next satellite sent by the Soviets after Sputnik 1 was Sputnik 2, launched on November 3, 1957, just a month later. This would put the first animal into orbit.[74][75]

US reaction to Sputnik

[edit]CIA assessment

[edit]At the latest, the successful start of Sputnik 2 with the satellite weighing more than 500 kg proved that the USSR had achieved a leading advantage in rocket technology. The CIA, initially astonished, estimated the launch weight of the rocket at 500 metric tons, requiring an initial thrust exceeding 1,000 tons, and assumed the use of a three-stage rocket. In a classified report, the agency described the event as a "stupendous scientific achievement" and concluded that the USSR had likely perfected an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of accurately targeting any location.[76] In reality, the launch weight of the Soviet rocket was 267 metric tons with an initial thrust of 410 tons with one and a half stages. The CIA's misjudgement was caused by extrapolating the parameters of the US Atlas rocket developed at the same time (launch weight 82 tons, initial thrust 135 tons, maximum payload of 70 kg for low Earth orbit).[77] In part, the favourable data of the Soviet launcher was based on concepts proposed by the German rocket scientists headed by Helmut Gröttrup on Gorodomlya Island, such as, among other things, the rigorous weight saving, the control of the residual fuel quantities and a reduced thrust to weight relation of 1.4 instead of usual factor 2.[78] The CIA had heard about such details already in January 1954 when it interrogated Göttrup after his return from the USSR but did not take him seriously.[79]

US reactions

[edit]The Soviet success raised a great deal of concern in the United States. For example, economist Bernard Baruch wrote in an open letter titled "The Lessons of Defeat" to the New York Herald Tribune: "While we devote our industrial and technological power to producing new model automobiles and more gadgets, the Soviet Union is conquering space. ... It is Russia, not the United States, who has had the imagination to hitch its wagon to the stars and the skill to reach for the moon and all but grasp it. America is worried. It should be."[80]

Eisenhower ordered project Vanguard to move up its timetable and launch its satellite much sooner than originally planned.[81] The December 6, 1957 Project Vanguard launch failure occurred at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. It was a monumental failure, exploding a few seconds after launch, and it became an international joke. The satellite appeared in newspapers under the names Flopnik, Stayputnik, Kaputnik,[82] and Dudnik.[83] In the United Nations, the Soviet delegate offered the US representative aid "under the Soviet program of technical assistance to backwards nations."[82] Only in the wake of this very public failure did von Braun's Redstone team get the go-ahead to launch their Jupiter-C rocket as soon as they could. In Britain, the US's Western Cold War ally, the reaction was mixed: some celebrated the fact that the Soviets had reached space first, while others feared the destructive potential that military uses of spacecraft might bring.[84] The Daily Express predicted that the US would catch up to and pass the USSR in space; "never doubt for a moment that America would be successful".[85]

Explorer

[edit]

On January 31, 1958, nearly four months after the launch of Sputnik 1, von Braun and the United States successfully launched its first satellite on a four-stage Juno I rocket derived from the US Army's Redstone missile, at Cape Canaveral.[86] The satellite Explorer 1 was 30.66 pounds (13.91 kg) in mass.[86] The payload of Explorer 1 weighed 18.35 pounds (8.32 kg). It carried a micrometeorite gauge and a Geiger-Müller tube. It passed in and out of the Earth-encompassing radiation belt with its 194-by-1,368-nautical-mile (360 by 2,534 km) orbit, therefore saturating the tube's capacity and proving what Dr. James Van Allen, a space scientist at the University of Iowa, had theorized.[86] The belt, named the Van Allen radiation belt, is a doughnut-shaped zone of high-level radiation intensity around the Earth above the magnetic equator.[87] Van Allen was also the man who designed and built the satellite instrumentation of Explorer 1. The satellite measured three phenomena: cosmic ray and radiation levels, the temperature in the spacecraft, and the frequency of collisions with micrometeorites. The satellite had no memory for data storage, therefore it had to transmit continuously.[88] The next successful mission was Explorer 3, launched later that month (March 26, 1958), which carried similar scientific instruments and successfully recorded cosmic ray data.[89][90][91]

Creation of NASA

[edit]On April 2, 1958, President Eisenhower reacted to the Soviet space lead in launching the first satellite by recommending to the US Congress that a civilian agency be established to direct nonmilitary space activities. Congress, led by Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson, responded by passing the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which Eisenhower signed into law on July 29, 1958. This law turned the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics into the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). It also created a Civilian-Military Liaison Committee, appointed by the President, responsible for coordinating the nation's civilian and military space programs.[92]

On October 21, 1959, Eisenhower approved the transfer of the Army's remaining space-related activities to NASA. On July 1, 1960, the Redstone Arsenal became NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, with von Braun as its first director. Development of the Saturn rocket family, which when mature gave the US parity with the Soviets in terms of lifting capability, was thus transferred to NASA.[93]

First mammals in space

[edit]

The US and the USSR sent animals into space to determine the safety of the environment before sending the first humans. The USSR used dogs for this purpose, and the US used monkeys and apes. The first mammal in space was Albert II, a rhesus monkey launched by the US on a sub-orbital flight on June 14, 1949, who died on landing due to a parachute malfunction.[94]

The USSR sent the dog Laika into orbit on Sputnik 2, the second satellite launched, on November 3, 1957, for an intended ten-day flight.[74] They did not yet have the technology to return Laika safely to Earth, and the government reported Laika died when the oxygen ran out,[95] but in October 2002 her true cause of death was reported as stress and overheating on the fourth orbit[96] due to failure of the air conditioning system.[97] At a Moscow press conference in 1998 Oleg Gazenko, a senior Soviet scientist involved in the project, stated "The more time passes, the more I'm sorry about it. We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog...".[98]

Early lunar probes

[edit]

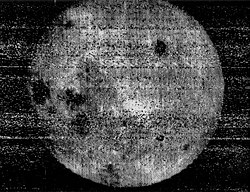

In 1958, Korolev upgraded the R-7 to be able to launch a 400-kilogram (880 lb) payload to the Moon. The Luna program began with three failed secret 1958 attempts to launch Luna E-1-class impactor probes.[99] The fourth attempt, Luna 1, launched successfully on January 2, 1959, but missed the Moon. The fifth attempt on June 18 also failed at launch. The 390-kilogram (860 lb) Luna 2 successfully impacted the Moon on September 14, 1959. The 278.5-kilogram (614 lb) Luna 3 successfully flew by the Moon and sent back pictures of its far side on October 7, 1959.[100]

The US first embarked on the Pioneer program in 1958 by launching the first probe, albeit ending in failure. A subsequent probe named Pioneer 1 was launched with the intention of orbiting the Moon only to result in a partial mission success when it reached an apogee of 113,800 km before falling back to Earth. The missions of Pioneer 2 and Pioneer 3 failed whereas Pioneer 4 had one partially successful lunar flyby in March 1959.[101][102]

Human spaceflight, space treaties, interplanetary probes (1961–1968)

[edit]The period from 1961 to 1968 began with the first men sent to space, the first robotic explorations of other planets; with missions to Venus and Mars conducted by both the Soviet Union and the United States, robotic landings on the Moon, and the gestation of US ambition to land a man on the Moon. The 1960s saw significant advancements in crewed spaceflight by both Cold War adversaries, as well as the first nuclear detonation in space, research into anti-satellite technology, and the signing of historic international outer space treaties.

First humans in space

[edit]Vostok

[edit]

The Soviets designed their first human space capsule using the same spacecraft bus as their Zenit spy satellite,[103] forcing them to keep the details and true appearance secret until after the Vostok program was over. The craft consisted of a spherical descent module with a mass of 2.46 tonnes (5,400 lb) and a diameter of 2.3 meters (7.5 ft), with a cylindrical inner cabin housing the cosmonaut, instruments, and escape system; and a biconic instrument module with a mass of 2.27 tonnes (5,000 lb), 2.25 meters (7.4 ft) long and 2.43 meters (8.0 ft) in diameter, containing the engine system and propellant. After reentry, the cosmonaut would eject at about 7,000 meters (23,000 ft) over the USSR and descend via parachute, while the capsule would land separately, because the descent module made an extremely rough landing that could have left a cosmonaut seriously injured.[104] The "Vostok spaceship" was first displayed at the July 1961 Tushino air show, mounted on its launch vehicle's third stage, with the nose cone in place concealing the spherical capsule. A tail section with eight fins was added in an apparent attempt to confuse western observers. This also appeared on official commemorative stamps and a documentary.[105] The Soviets finally revealed the true appearance of their Vostok capsule at the April 1965 Moscow Economic Exhibition.[106]

On April 12, 1961, the USSR surprised the world by launching Yuri Gagarin into a single, 108-minute orbit around the Earth in a craft called Vostok 1.[104] They dubbed Gagarin the first cosmonaut, roughly translated from Russian and Greek as "sailor of the universe". Gagarin's capsule was flown in automatic mode, since doctors did not know what would happen to a human in the weightlessness of space; but Gagarin was given an envelope containing the code that would unlock manual control in an emergency.[104]

Gagarin became a national hero of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, and a worldwide celebrity. Moscow and other cities in the USSR held mass demonstrations, the scale of which was second only to the World War II Victory Parade of 1945.[107] April 12 was declared Cosmonautics Day in the USSR, and is celebrated today in Russia as one of the official "Commemorative Dates of Russia."[108] In 2011, it was declared the International Day of Human Space Flight by the United Nations.[109]

The USSR demonstrated 24-hour launch pad turnaround and launched two piloted spacecraft, Vostok 3 and Vostok 4, in essentially identical orbits, on August 11 and 12, 1962.[110] The two spacecraft came within approximately 6.5 kilometers (3.5 nautical miles) of one another, close enough for radio communication,[111] but then drifted as far apart as 2,850 kilometers (1,540 nautical miles). The Vostok had no maneuvering rockets to keep the two craft a controlled distance apart.[112] Vostok 4 also set a record of nearly four days in space. The first woman, Valentina Tereshkova, was launched into space on Vostok 6 on June 16, 1963,[113] as (possibly) a medical experiment. She was the only one to fly of a small group of female parachutist factory workers (unlike the male cosmonauts who were military test pilots),[114] chosen by the head of cosmonaut training because he read a tabloid article about the "Mercury 13" group of women wanting to become astronauts, and got the mistaken idea that NASA was actually entertaining this.[115][113] Five months after her flight, Tereshkova married Vostok 3 cosmonaut Andriyan Nikolayev,[116] and they had a daughter.[117]

Mercury

[edit]

The US Air Force had been developing a program to launch the first man in space, named Man in Space Soonest. This program studied several different types of one-man space vehicles, settling on a ballistic re-entry capsule launched on a derivative Atlas missile, and selecting a group of nine candidate pilots. After NASA's creation, the program was transferred over to the civilian agency's Space Task Group and renamed Project Mercury on November 26, 1958. The Mercury spacecraft was designed by the STG's chief engineer Maxime Faget. NASA selected a new group of astronaut (from the Greek for "star sailor") candidates from Navy, Air Force and Marine test pilots, and narrowed this down to a group of seven for the program. Capsule design and astronaut training began immediately, working toward preliminary suborbital flights on the Redstone missile, followed by orbital flights on the Atlas. Each flight series would first start unpiloted, then carry a non-human primate, then finally humans.[118]

The Mercury spacecraft's principal designer was Maxime Faget, who started research for human spaceflight during the time of the NACA.[119] It consisted of a conical capsule with a cylindrical pack of three solid-fuel retro-rockets strapped over a beryllium or fiberglass heat shield on the blunt end. Base diameter at the blunt end was 6.0 feet (1.8 m) and length was 10.8 feet (3.3 m); with the launch escape system added, the overall length was 25.9 feet (7.9 m).[120] With 100 cubic feet (2.8 m3) of habitable volume, the capsule was just large enough for a single astronaut.[121] The first suborbital spacecraft weighed 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg); the heaviest, Mercury-Atlas 9, weighed 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) fully loaded.[122] On reentry, the astronaut would stay in the craft through splashdown by parachute in the Atlantic Ocean.

On May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American in space, launching in a ballistic trajectory on Mercury-Redstone 3, in a spacecraft he named Freedom 7.[123] Though he did not achieve orbit like Gagarin, he was the first person to exercise manual control over his spacecraft's attitude and retro-rocket firing.[124] After his successful return, Shepard was celebrated as a national hero, honored with parades in Washington, New York and Los Angeles, and received the NASA Distinguished Service Medal from President John F. Kennedy.[125]

American Virgil "Gus" Grissom repeated Shepard's suborbital flight in Liberty Bell 7 on July 21, 1961.[126] Almost a year after the Soviet Union put a human into orbit, astronaut John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, on February 20, 1962.[127] His Mercury-Atlas 6 mission completed three orbits in the Friendship 7 spacecraft, and splashed down safely in the Atlantic Ocean, after a tense reentry, due to what falsely appeared from the telemetry data to be a loose heat-shield.[127] On February 23, 1962, President Kennedy awarded Glenn with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal in a ceremony at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.[128] As the first American in orbit, Glenn became a national hero, and received a ticker-tape parade in New York City, reminiscent of that given for Charles Lindbergh.

The United States launched three more Mercury flights after Glenn's: Aurora 7 on May 24, 1962, duplicated Glenn's three orbits, Sigma 7 on October 3, 1962, six orbits, and Faith 7 on May 15, 1963, 22 orbits (32.4 hours), the maximum capability of the spacecraft. NASA at first intended to launch one more mission, extending the spacecraft's endurance to three days, but since this would not beat the Soviet record, it was decided instead to concentrate on developing Project Gemini.[129]

Kennedy aims for a crewed Moon landing

[edit]These are extraordinary times. And we face an extraordinary challenge. Our strength, as well as our convictions, have imposed upon this nation the role of leader in freedom's cause.

... if we are to win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny, the dramatic achievements in space which occurred in recent weeks should have made clear to us all, as did the Sputnik in 1957, the impact of this adventure on the minds of men everywhere, who are attempting to make a determination of which road they should take. ... Now it is time to take longer strides – time for a great new American enterprise – time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.

... Recognizing the head start obtained by the Soviets with their large rocket engines, which gives them many months of lead-time, and recognizing the likelihood that they will exploit this lead for some time to come in still more impressive successes, we nevertheless are required to make new efforts on our own.

... I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space, and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.

... Let it be clear that I am asking the Congress and the country to accept a firm commitment to a new course of action—a course which will last for many years and carry very heavy costs: 531 million dollars in fiscal '62—an estimated seven to nine billion dollars additional over the next five years. If we are to go only half way, or reduce our sights in the face of difficulty, in my judgment it would be better not to go at all.

Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs, May 25, 1961[10]

Before Gagarin's flight, US President John F. Kennedy's support for America's piloted space program was lukewarm. Jerome Wiesner of MIT, who served as a science advisor to presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy, and himself an opponent of sending humans into space, remarked, "If Kennedy could have opted out of a big space program without hurting the country in his judgment, he would have."[130] As late as March 1961, when NASA administrator James E. Webb submitted a budget request to fund a Moon landing before 1970, Kennedy rejected it because it was simply too expensive.[131] Some were surprised by Kennedy's eventual support of NASA and the space program because of how often he had attacked the Eisenhower administration's inefficiency during the election.[132]

Gagarin's flight changed this; now Kennedy sensed the humiliation and fear on the part of the American public over the Soviet lead. Additionally, the Bay of Pigs invasion, planned before his term began but executed during it, was an embarrassment to his administration due to the colossal failure of the US forces.[133] Looking for something to save political face, he sent a memo dated April 20, 1961, to Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, asking him to look into the state of America's space program, and into programs that could offer NASA the opportunity to catch up.[134] The two major options at the time were either the establishment of an Earth orbital space station or a crewed landing on the Moon. Johnson, in turn, consulted with von Braun, who answered Kennedy's questions based on his estimates of US and Soviet rocket lifting capability.[135] Based on this, Johnson responded to Kennedy, concluding that much more was needed to reach a position of leadership, and recommending that the crewed Moon landing was far enough in the future that the US had a fighting chance to achieve it first.[136]

Kennedy ultimately decided to pursue what became the Apollo program, and on May 25 took the opportunity to ask for Congressional support in a Cold War speech titled "Special Message on Urgent National Needs". Full text ![]() He justified the program in terms of its importance to national security, and its focus of the nation's energies on other scientific and social fields.[137] He rallied popular support for the program in his "We choose to go to the Moon" speech, on September 12, 1962, before a large crowd at Rice University Stadium, in Houston, Texas, near the construction site of the new Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center facility.[137] Full text

He justified the program in terms of its importance to national security, and its focus of the nation's energies on other scientific and social fields.[137] He rallied popular support for the program in his "We choose to go to the Moon" speech, on September 12, 1962, before a large crowd at Rice University Stadium, in Houston, Texas, near the construction site of the new Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center facility.[137] Full text ![]()

Khrushchev responded to Kennedy's challenge with silence, refusing to publicly confirm or deny the Soviets were pursuing a "Moon race".[138] As later disclosed, the Soviet Union secretly pursued two competing crewed lunar programs. Soviet Decree 655–268, On Work on the Exploration of the Moon and Mastery of Space, issued in August 1964, directed Vladimir Chelomei to develop a Moon flyby program with a projected first flight by the end of 1966, and directed Korolev to develop the Moon landing program with a first flight by the end of 1967.[139] In September 1965, Chelomei's flyby program was assigned to Korolev, who redesigned the cislunar mission to use his own Soyuz 7K-L1 spacecraft and Chelomei's Proton rocket. After Korolev's death in January 1966, another government decree of February 1967 moved the first crewed flyby to mid-1967, and the first crewed landing to the end of 1968.[140][141]

Proposed joint US-USSR program

[edit]After a first US-USSR Dryden-Blagonravov agreement and cooperation on the Echo II balloon satellite in 1962,[16] President Kennedy proposed on September 20, 1963, in a speech before the United Nations General Assembly, that the United States and the Soviet Union join forces in an effort to reach the Moon.[142] Kennedy thus changed his mind regarding the desirability of the space race, preferring instead to ease tensions with the Soviet Union by cooperating on projects such as a joint lunar landing.[143] Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev initially rejected Kennedy's proposal.[144] However, on October 2, 1997, it was reported that Khrushchev's son Sergei claimed Khrushchev was poised to accept Kennedy's proposal at the time of Kennedy's assassination on November 22, 1963. During the next few weeks he reportedly concluded that both nations might realize cost benefits and technological gains from a joint venture, and decided to accept Kennedy's offer based on a measure of rapport during their years as leaders of the world's two superpowers, but changed his mind and dropped the idea since he lacked the same trust for Kennedy's successor, Lyndon Johnson.[144]

Some cooperation in robotic space exploration nevertheless did take place,[145] such as a combined Venera 4–Mariner 5 data analysis under a joint Soviet–American working group of COSPAR in 1969, allowing a more complete drawing of the profile of the atmosphere of Venus.[146][147] Eventually the Apollo–Soyuz mission was realized afterall, which furthermore laid the foundations for the Shuttle-Mir program and the ISS.

As President, Johnson steadfastly pursued the Gemini and Apollo programs, promoting them as Kennedy's legacy to the American public. One week after Kennedy's death, he issued Executive Order 11129 renaming the Cape Canaveral and Apollo launch facilities after Kennedy.

Lunar probes and robotic landers

[edit]

The Ranger program, started in 1959 by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, aimed to conduct hard impacts on the Moon and had its first success in 1962, after three failures due to launch aborts (Ranger 1 and Ranger 2) and a failure to reach the Moon (Ranger 3), when the 730-pound (330 kg) Ranger 4 became the first US spacecraft to reach the Moon, but its solar panels and navigational system failed near the Moon and it impacted the far side without returning any scientific data. Ranger 5 ran out of power and missed the Moon by 725 kilometers (391 nmi) on October 21, 1962. The first successful Ranger mission was the 806-pound (366 kg) Block III Ranger 7 which impacted on July 31, 1964.[148] Ranger had three successful impacts out of nine attempts.[149]

In 1963, the Soviet Union's "2nd Generation" Luna programme was less successful than the earlier Luna probes; Luna 4, Luna 5, Luna 6, Luna 7, and Luna 8 were all met with mission failures. However, in 1966 the Luna 9 achieved the first soft-landing on the Moon, and successfully transmitted photography from the surface.[150] Luna 10 marked the first man-made object to establish an orbit around the Moon,[151] followed by Luna 11, Luna 12, and Luna 14 which also successfully established orbits. Luna 12 was able to transmit detailed photography of the surface from orbit.[152] Luna 10, 12, and Luna 14 conducted Gamma ray spectrometry of the Moon, among other tests.

The Zond programme was orchestrated alongside the Luna programme with Zond 1 and Zond 2 launching in 1964, intended as flyby missions, however both failed.[153][154] Zond 3 however was successful, and transmitted high quality photography from the far side of the moon.[155][156]

Partly to aid the Apollo missions, the Surveyor program was conducted by NASA, with five successful soft landings out of seven attempts from 1966 to 1968. The Lunar Orbiter program had five successes out of five attempts in 1966–1967.[157][158]

In late 1966, Luna 13 became the third spacecraft to make a soft-landing on the Moon, with the American Surveyor 1 having now taken second. Luna 13 made use of inflatable air-bags to soften it's landing.[159][160][161] Surveyor 1 was a 995 kg lander, notably larger than the 112 kg Luna 13 E-6M lander.[159][162] Surveyor 1 was equipped with a Doppler velocity sensing system that fed information into the spacecraft computer to implement a controllable descent to the surface. Each of the three landing pads also carried aircraft-type shock absorbers and strain gauges to provide data on landing characteristics, important for future Apollo missions.[163][164]

Surveyor 3, which successfully touched down on the Moon April 20, 1967, carried a 'surface sampler' which facilitated tests of the Lunar soil. Based on these experiments, scientists concluded that lunar soil had a consistency similar to wet sand, with a bearing strength of about 10 pounds per square inch (0.7 kilograms per square centimeter, or 98 kilopascals), which was concluded to be solid enough to support an Apollo Lunar Module.[165] The Surveyor 3 lander would be later visited by Apollo 12 astronauts.[166]

On Nov. 17, 1967, before mission termination, Surveyor 6 fired its thrusters for 2.5 seconds, becoming the first spacecraft launched from the lunar surface. It rose about 10 feet (3 meters) before landing 8 feet (2.5 meters) west of its original spot. Cameras then examined the original landing site to assess the soil's properties.[167][168]

First interplanetary probes

[edit]From the early 1960s both Cold War adversaries almost simultaneously initiated their own programmes which sought to reach other planets in the Solar System for the first time; namely Venus and Mars.

Venus

[edit]

Venus was of great interest in the field of planetary science due to its thick and opaque atmosphere, the atmospheres of other planets being a novel area of research at the time.

In 1961 the Venera Programme was initiated by the Soviet Union, with the launch of Venera 1. The programme would go on to mark many firsts in the exploration of another planet. Despite the later successes however, Venera 1 and Venera 2, intended to flyby Venus, resulted in failure due to losses of contact.[169][170]

NASA would then initiate the Mariner program with the launch of Mariner 1 and Mariner 2. Mariner 1 failed shortly after launch,[171] however Mariner 2 would become the first man-made object to flyby another planet in December 1962 when the probe passed by Venus.[172][173]

Later in 1965/66, Venera 3, marked the first time a man-made object made contact with another planet after it impacted Venus on March 1, 1966, despite operational difficulties resulting in loss of contact with the craft.[174]

In 1967, Mariner 5 flew by Venus and conducted atmospheric analysis.[175]

Mars

[edit]In 1964, NASA's Mariner 4 became the first successful Mars flyby, transmitting 21 pictures of the planets surface. This was followed by Mariner 6 and 7 in 1969.

First crewed spacecraft

[edit]Focused by the commitment to a Moon landing, in January 1962 the US announced Project Gemini, a two-person spacecraft that would support the later three-person Apollo by developing the key spaceflight technologies of space rendezvous and docking of two craft, flight durations of sufficient length to go to the Moon and back, and extra-vehicular activity to perform work outside the spacecraft.[176][177]

Meanwhile, Korolev had planned further long-term missions for the Vostok spacecraft, and had four Vostoks in various stages of fabrication in late 1963 at his OKB-1 facilities.[178] The Americans' announced plans for Gemini represented major advances over the Mercury and Vostok capsules, and Korolev felt the need to try to beat the Americans to many of these innovations.[178] He had already begun designing the Vostok's replacement, the next-generation Soyuz, a multi-cosmonaut spacecraft that had at least the same capabilities as the Gemini spacecraft.[179] Soyuz would not be available for at least three years, and it could not be called upon to deal with this new American challenge in 1964 or 1965.[180] Political pressure in early 1964 – which some sources claim was from Khrushchev while other sources claim was from other Communist Party officials – pushed him to modify his four remaining Vostoks to beat the Americans to new space firsts in the size of flight crews, and the duration of missions.[178]

Voskhod

[edit]

Korolev's conversion of his surplus Vostok capsules to the Voskhod spacecraft allowed the Soviet space program to beat the Gemini program in achieving the first spaceflight with a multi-person crew, and the first "spacewalk". Gemini took a year longer than planned to make its first flight, so Voskhod 1 became the first spaceflight with a three-person crew on October 12, 1964.[181] The USSR touted another "technological achievement" during this mission: it was the first space flight during which cosmonauts performed in a shirt-sleeve-environment.[182] However, flying without spacesuits was not due to safety improvements in the Soviet spacecraft's environmental systems; rather this was because the craft's limited cabin space did not allow for spacesuits. Flying without spacesuits exposed the cosmonauts to significant risk in the event of potentially fatal cabin depressurization.[182] This was not repeated until the US Apollo Command Module flew in 1968; the command module cabin was designed to transport three astronauts in a low pressure, pure oxygen shirt-sleeve environment while in space.

On March 18, 1965, about a week before the first piloted Project Gemini space flight, the USSR launched the two-cosmonaut Voskhod 2 mission with Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov.[183] Voskhod 2's design modifications included the addition of an inflatable airlock to allow for extravehicular activity (EVA), also known as a spacewalk, while keeping the cabin pressurized so that the capsule's electronics would not overheat.[184] Leonov performed the first-ever EVA as part of the mission.[183] A fatality was narrowly avoided when Leonov's spacesuit expanded in the vacuum of space, preventing him from re-entering the airlock.[185] To overcome this, he had to partially depressurize his spacesuit to a potentially dangerous level.[185] He succeeded in safely re-entering the spacecraft, but he and Belyayev faced further challenges when the spacecraft's atmospheric controls flooded the cabin with 45% pure oxygen, which had to be lowered to acceptable levels before re-entry.[186] The reentry involved two more challenges: an improperly timed retrorocket firing caused the Voskhod 2 to land 386 kilometers (240 mi) off its designated target area, the city of Perm; and the instrument compartment's failure to detach from the descent apparatus caused the spacecraft to become unstable during reentry.[186]

By October 16, 1964, Leonid Brezhnev and a small cadre of high-ranking Communist Party officials deposed Khrushchev as Soviet government leader a day after Voskhod 1 landed, in what was called the "Wednesday conspiracy".[187] The new political leaders, along with Korolev, ended the technologically troublesome Voskhod program, canceling Voskhod 3 and 4, which were in the planning stages, and started concentrating on reaching the Moon.[188] Voskhod 2 ended up being Korolev's final achievement before his death on January 14, 1966, as it became the last of the space firsts that the USSR achieved during the early 1960s. According to historian Asif Siddiqi, Korolev's accomplishments marked "the absolute zenith of the Soviet space program, one never, ever attained since."[7] There was a two-year pause in Soviet piloted space flights while Voskhod's replacement, the Soyuz spacecraft, was designed and developed.[189]

Gemini

[edit]

Though delayed a year to reach its first flight, Gemini was able to take advantage of the USSR's two-year hiatus after Voskhod, which enabled the US to catch up and surpass the previous Soviet superiority in piloted spaceflight. Gemini had ten crewed missions between March 1965 and November 1966: Gemini 3, Gemini 4, Gemini 5, Gemini 6A, Gemini 7, Gemini 8, Gemini 9A, Gemini 10, Gemini 11, and Gemini 12; and accomplished the following:

- Every mission demonstrated the ability to adjust the crafts' inclination and apsis without issue.

- Gemini 5 demonstrated eight-day endurance, long enough for a round trip to the Moon. Gemini 7 demonstrated a fourteen-day endurance flight.

- Gemini 6A demonstrated rendezvous and station-keeping with Gemini 7 for three consecutive orbits at distances as close as 1 foot (0.30 m).[190] Gemini 9A also achieved rendezvous with an Agena Target Vehicle (ATV).

- Rendezvous and docking with the ATV was achieved on Gemini 8, 10, 11, and 12. Gemini 11 achieved the first direct-ascent rendezvous with its Agena target on the first orbit.

- Extravehicular activity (EVA) was perfected through increasing practice on Gemini 4, 9A, 10, 11, and 12. On Gemini 12, Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin spent over five hours working comfortably during three (EVA) sessions, finally proving that humans could perform productive tasks outside their spacecraft.

- Gemini 10, 11, and 12 used the ATV's engine to make large changes in its orbit while docked. Gemini 11 used the Agena's rocket to achieve a crewed Earth orbit record apogee of 742 nautical miles (1,374 km).

Gemini 8 experienced the first in-space mission abort on March 17, 1966, just after achieving the world's first docking, when a stuck or shorted thruster sent the craft into an uncontrolled spin. Command pilot Neil Armstrong was able to shut off the stuck thruster and stop the spin by using the re-entry control system.[191] He and his crewmate David Scott landed and were recovered safely.[192]

Most of the novice pilots on the early missions would command the later missions. In this way, Project Gemini built up spaceflight experience for the pool of astronauts for the Apollo lunar missions. With the completion of Gemini, the US had demonstrated many of the key technologies necessary to make Kennedy's goal of landing a man on the Moon, namely crewed spacecraft docking, with the exception of developing a large enough launch vehicle.[193]

Soviet crewed Moon programs

[edit]

Korolev's design bureau produced two prospectuses for circumlunar spaceflight (March 1962 and May 1963), the main spacecraft for which were early versions of his Soyuz design. At the same time, another bureau, OKB-52, headed by Vladimir Chelomey, was developing the LK-1 lunar flyby spacecraft, which would be launched by Chelomey's Proton UR-500 rocket. The Soviet government rejected Korolev's proposals, opting to support Chelomey's project, who gained favor with Khrushchev by employing his son.[194]

Officially, the Soviet lunar program was established on August 3, 1964, with the adoption of Soviet Communist Party Central Committee Command 655-268 (On Work on the Exploration of the Moon and Mastery of Space).[140] The circumlunar flights were planned to occur in 1967, and the landings to start in 1968, intending to land a person on the Moon before the Apollo flights.[195] Both of the bureaus submitted their projects for a crewed lunar landing.[140]

Korolev's lunar landing program was designated N1/L3, for its N1 super rocket and a more advanced Soyuz 7K-L3 spacecraft, also known as the lunar orbital module ("Lunniy Orbitalny Korabl", LOK), with a crew of two. A separate lunar lander ("Lunniy Korabl", LK), would carry a single cosmonaut to the lunar surface.[195]

The N1/L3 launch vehicle had three stages to Earth orbit, a fourth stage for Earth departure, and a fifth stage for lunar landing assist. The combined space vehicle was roughly the same height and takeoff mass as the three-stage US Apollo-Saturn V and exceeded its takeoff thrust by 28% (45,400 kN vs. 33,000 kN.[196] The N1/3L was never successfully tested, the first flight suffered a fire in the first-stage Block A due to a loose bolt, leading to a catastrophic explosion 70 seconds into the flight. Further variations of the N1 had similar catastrophic results in testing.[197] If successful, the N1 would have been capable of carrying a 95 metric tons payload into low earth orbit.[197] The Saturn V comparatively used liquid hydrogen fuel in its two upper stages, and carried a 140.6 metric tons payload to orbit,[198][197] enough for a three-person orbiter and two-person lander.

Chelomey's program assumed using a direct ascent lander based on the LK-1, LK-700, which would be launched using his proposed UR-700 rocket. Following Khrushchev's ouster from power, Chelomey lost his support in the Soviet government, and his proposal didn't receive any funding. Additionally, in August 1965, due to Korolev's opposition, work on the LK-1 was suspended, and later stopped completely. As a replacement, the circumlunar mission would use a stripped-down Soyuz 7K-L1 "Zond", while still retaining the Proton UR-500 booster. To fit two crewmembers, the Zond had to omit the Soyuz orbital module, sacrificing equipment for habitable cabin volume.[194][199]

Outer space treaties

[edit]

The US and USSR began discussions on the peaceful uses of space as early as 1958, presenting issues for debate to the United Nations,[200][201][202] which created a Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space in 1959.[203]

On May 10, 1962, Vice President Johnson addressed the Second National Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Space revealing that the United States and the USSR both supported a resolution passed by the Political Committee of the UN General Assembly in December 1962, which not only urged member nations to "extend the rules of international law to outer space," but to also cooperate in its exploration. Following the passing of this resolution, Kennedy commenced his communications proposing a cooperative American and Soviet space program.[204]

In 1963, the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was signed by more than 100 signatories, including both the United States and the Soviet Union. This treaty followed the US test of a nuclear bomb detonated in outer space the year earlier called Starfish Prime.

The UN ultimately created a Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, which was signed by the United States, the USSR, and the United Kingdom on January 27, 1967, and came into force the following October 10.[205]

This treaty:

- bars party States from placing weapons of mass destruction in Earth orbit, on the Moon, or any other celestial body;

- exclusively limits the use of the Moon and other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes, and expressly prohibits their use for testing weapons of any kind, conducting military maneuvers, or establishing military bases, installations, and fortifications;

- declares that the exploration of outer space shall be done to benefit all countries and shall be free for exploration and use by all the States;

- explicitly forbids any government from claiming a celestial resource such as the Moon or a planet, claiming that they are the common heritage of mankind, "not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means". However, the State that launches a space object retains jurisdiction and control over that object;

- holds any State liable for damages caused by their space object;

- declares that "the activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty", and "States Parties shall bear international responsibility for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities"; and

- "A State Party to the Treaty which has reason to believe that an activity or experiment planned by another State Party in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, would cause potentially harmful interference with activities in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, may request consultation concerning the activity or experiment."

The treaty remains in force, signed by 107 member states. – As of July 2017[update]

Anti-Satellite research

[edit]Istrebitel-sputnikov

[edit]

In November 1968, dismay gripped the United States Central Intelligence Agency when a successful satellite destruction simulation was successfully orchestrated by the Soviet Union.[206] As a part of the Istrebitel Sputnikov anti-satellite weapons research programme, the Kosmos 248 Soviet satellite was successfully destroyed by Kosmos 252 which was able to intercept within the 5 km 'kill radius' and destroyed Kosmos 248 by detonating its onboard warhead. This wasn't the beginning of the programme, years earlier intercept attempts had begun with maneuvering test of the Polyot satellites in 1964.[207][208][209][210]

SAINT

[edit]Possibly as a response to the Soviet programme, the United States began Project SAINT, which was intended to provide anti-satellite capability to be used in the case of war with the Soviet Union.[211][206][212] However, less is known about the mission profiles of this project compared to the Soviet programme, and the project was cancelled due to budget constraints.[212]

Disaster strikes both sides

[edit]In 1967, both nations' space programs faced serious challenges that brought them to temporary halts.

Apollo 1

[edit]

On January 27, 1967, the same day the US and USSR signed the Outer Space Treaty, the crew of the first crewed Apollo mission, Command Pilot Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Senior Pilot Ed White, and Pilot Roger Chaffee, were killed in a fire that swept through their spacecraft cabin during a ground test, less than a month before the planned February 21 launch. An investigative board determined the fire was probably caused by an electrical spark and quickly grew out of control, fed by the spacecraft's atmosphere of pure oxygen at greater than one standard atmosphere. Crew escape was made impossible by inability to open the plug door hatch cover against the internal pressure.[213] The board also found design and construction flaws in the spacecraft, and procedural failings, including failure to appreciate the hazard of the pure-oxygen atmosphere, as well as inadequate safety procedures.[213] All these flaws had to be corrected over the next twenty-two months until the first piloted flight could be made.[213] Mercury and Gemini veteran Grissom had been a favored choice of Deke Slayton, NASA's Director of Flight Crew Operations, to make the first piloted landing.[214]

Soyuz 1

[edit]

On April 24, 1967, the single pilot of Soyuz 1, Vladimir Komarov, became the first in-flight spaceflight fatality. The mission was planned to be a three-day test, to include the first Soviet docking with an unpiloted Soyuz 2, but the mission was plagued with problems. Problems began shortly after launch when one solar panel failed to unfold, leading to a shortage of power for the spacecraft's systems. Further problems with the orientation detectors complicated maneuvering the craft. By orbit 13, the automatic stabilisation system was completely dead, and the manual system was only partially effective.[215] The mission was aborted, Soyuz 1 fired its retrorockets and reentered the Earth's atmosphere. During the emergency re-entry, a fault in the landing parachute system caused the primary chute to fail, and the reserve chute became tangled with the drogue chute, causing descent speed to reach as high as 40 m/s (140 km/h; 89 mph). Shortly thereafter, Soyuz 1 impacted the ground 3 km (1.9 mi) west of Karabutak, and was found on fire. The official autopsy states Komarov died of blunt force trauma on impact.[216][217][218] In the US during subsequent years, stories began circulating that in his last transmissions Komarov cursed the engineers and flight staff as he descended, or even that he cursed the Soviet leadership, and that these transmissions were received by an NSA listening station near Istanbul.[219][220][221] This would contradict Soviet records of the radio transcripts, and historians such as Asif Azam Siddiqi and Robert Pearlman regard these claims to be fabrications.[222][223]

Both programs recover

[edit]

The United States recovered from the Apollo 1 fire, fixing the fatal flaws in an improved version of the Block II command module. The US proceeded with unpiloted test launches of the Saturn V launch vehicle (Apollo 4 and Apollo 6) and the Lunar Module (Apollo 5) during the latter half of 1967 and early 1968.[224] The first Saturn V flight was an unqualified success, and although the second suffered some non-catastrophic engine failures, it was considered a partial success and the launcher achieved human rating qualification. Apollo 1's mission to check out the Apollo Command and Service Module in Earth orbit was accomplished by Grissom's backup crew on Apollo 7, launched on October 11, 1968.[225] The eleven-day mission was a total success, as the spacecraft performed a virtually flawless mission, paving the way for the United States to continue with its lunar mission schedule.[226]

The Soviet Union also fixed the parachute and control problems with Soyuz, and the next piloted mission Soyuz 3 was launched on October 26, 1968.[227] The goal was to complete Komarov's rendezvous and docking mission with the un-piloted Soyuz 2.[227] Ground controllers brought the two craft to within 200 meters (660 ft) of each other, then cosmonaut Georgy Beregovoy took control.[227] He got within 40 meters (130 ft) of his target, but was unable to dock before expending 90 percent of his maneuvering fuel, due to a piloting error that put his spacecraft into the wrong orientation and forced Soyuz 2 to automatically turn away from his approaching craft.[227] The first docking of Soviet spacecraft was finally realized in January 1969 by the Soyuz 4 and Soyuz 5 missions. It was the first-ever docking of two crewed spacecraft, and the first transfer of crew from one space vehicle to another.[228]

The Soviet Zond spacecraft was not yet ready for piloted circumlunar missions in 1968, after six unsuccessful automated test launches: Kosmos 146 on March 10, 1967; Kosmos 154 on April 8, 1967; Zond 1967A on September 28, 1967; Zond 1967B on November 22, 1967; Zond 1968A on April 23, 1968; and Zond 1968B in July 1968.[229] Zond 4 was launched on March 2, 1968, and successfully made a circumlunar flight,[230] but encountered problems with its Earth reentry on March 9, and was ordered destroyed by an explosive charge 15,000 meters (49,000 ft) over the Gulf of Guinea.[231] The Soviet official announcement said that Zond 4 was an automated test flight which ended with its intentional destruction, due to its recovery trajectory positioning it over the Atlantic Ocean instead of over the USSR.[230]

During the summer of 1968, the Apollo program hit another snag: the first pilot-rated Lunar Module (LM) was not ready for orbital tests in time for a December 1968 launch. NASA planners overcame this challenge by changing the mission flight order, delaying the first LM flight until March 1969, and sending Apollo 8 into lunar orbit without the LM in December.[232] This mission was in part motivated by intelligence rumors the Soviet Union might be ready for a piloted Zond flight in late 1968.[233] In September 1968, Zond 5 made a circumlunar flight with tortoises on board and returned safely to Earth, accomplishing the first successful water landing of the Soviet space program in the Indian Ocean.[234] It also scared NASA planners, as it took them several days to figure out that it was only an automated flight, not piloted, because voice recordings were transmitted from the craft en route to the Moon.[235] On November 10, 1968, another automated test flight, Zond 6, was launched. It encountered difficulties in Earth reentry, and depressurized and deployed its parachute too early, causing it to crash-land only 16 kilometers (9.9 mi) from where it had been launched six days earlier.[236] It turned out there was no chance of a piloted Soviet circumlunar flight during 1968, due to the unreliability of the Zonds.[237]

On December 21, 1968, Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders became the first humans to ride the Saturn V rocket into space, on Apollo 8. They also became the first to leave low-Earth orbit and go to another celestial body, entering lunar orbit on December 24.[238] They made ten orbits in twenty hours, and transmitted one of the most watched TV broadcasts in history, with their Christmas Eve program from lunar orbit, which concluded with a reading from the biblical Book of Genesis.[238] Two and a half hours after the broadcast, they fired their engine to perform the first trans-Earth injection to leave lunar orbit and return to the Earth.[238] Apollo 8 safely landed in the Pacific Ocean on December 27, in NASA's first dawn splashdown and recovery.[238]

The American Lunar Module was finally ready for a successful piloted test flight in low Earth orbit on Apollo 9 in March 1969. The next mission, Apollo 10, conducted a "dress rehearsal" for the first landing in May 1969, flying the LM in lunar orbit as close as 47,400 feet (14.4 km) above the surface, the point where the powered descent to the surface would begin.[239] With the LM proven to work well, the next step was to attempt the landing.

Unknown to the Americans, the Soviet Moon program was in deep trouble.[237] After two successive launch failures of the N1 rocket in 1969, Soviet plans for a piloted landing suffered delay.[240] The launch pad explosion of the N-1 on July 3, 1969, was a significant setback.[241] The rocket hit the pad after an engine shutdown, destroying itself and the launch facility.[241] Without the N-1 rocket, the USSR could not send a large enough payload to the Moon to land a human and return him safely.[242]

Men on the Moon, space stations, space shuttles (1969–1991)

[edit]The latter period of the space race began with the United States landing the first men on the Moon, and was followed by the Soviets operating the first space stations and putting the first robotic landers on Venus and Mars, the US space shuttles marking the first significant reusable space vehicles, and a cooling down of tensions with the first docking between a Soviet and American vessel.

First humans on the Moon

[edit]

Apollo 11 was prepared with the goal of a July landing in the Sea of Tranquility, just half a year after the first crewed flight to the Moon.[243] The crew, selected in January 1969, consisted of commander (CDR) Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Michael Collins, and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin.[244] They trained for the mission until just before the launch day.[245] On July 16, 1969, at 9:32 am EDT, the Saturn V rocket, AS-506, lifted off from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39 in Florida.[246]

The trip to the Moon took just over three days.[247] After achieving orbit, Armstrong and Aldrin transferred into the Lunar Module named Eagle, leaving Collins in the Command and Service Module Columbia, and began their descent. Despite the interruption of alarms from an overloaded computer caused by an antenna switch left in the wrong position, Armstrong took over manual flight control at about 180 meters (590 ft) to correct a slight downrange guidance error, and set the Eagle down on a safe landing spot at 20:18:04 UTC, July 20, 1969 (3:17:04 pm CDT). Six hours later, at 02:56 UTC, July 21 (9:56 pm CDT July 20), Armstrong left the Eagle to become the first human to set foot on the Moon.[248]

The first step was witnessed on live television by at least one-fifth of the population of Earth, or about 723 million people.[249] His first words when he stepped off the LM's landing footpad were, "That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."[248] Aldrin joined him on the surface almost 20 minutes later.[250] Altogether, they spent just under two and one-quarter hours outside their craft.[251] The next day, they performed the first crewed launch from another celestial body, and rendezvoused back with Collins in Columbia.[252] But before they return ascended the Space Race came to a particular culmination.[253] A few days before Apollo 11 left Earth, the Soviet Union launched the Luna 15 probe, entering lunar orbit just before Apollo 11 and eventually sharing it with Apollo 11. Aware of Luna 15, Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman was asked to use his goodwill contacts in the Soviet Union to prevent any collision. Subsequently, in one of the first instances of Soviet–American space communication the Soviet Union released Luna 15's flight plan to ensure it would not collide with Apollo 11, although its exact mission was not publicized.[254] But as Apollo 11 was wrapping up surface activities, the Soviet mission command hastened Luna 15 and attempted its robotic sample-return mission before Apollo 11 would return. As Luna 15 descended just two hours before Apollo 11's launch and impacted at 15:50 UTC some hundred kilometers away from Apollo 11, British astronomers monitoring Luna 15 recorded the situation, with one commenting:“I say, this has really been drama of the highest order”.[255]

Apollo 11 left lunar orbit and returned to Earth, landing safely in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969.[256] When the spacecraft splashed down, 2,982 days had passed since Kennedy's commitment to landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth before the end of the decade; the mission was completed with 161 days to spare.[257] With the safe completion of the Apollo 11 mission, the Americans won the race to the Moon.[258]

Armstrong and his crew became worldwide celebrities, feted with ticker-tape parades on August 13 in New York City and Chicago, attended by an estimated six million.[259][260] That evening in Los Angeles they were honored at an official state dinner attended by members of Congress, 44 governors, the Chief Justice of the United States, and ambassadors from 83 nations. The President and Vice president presented each astronaut with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[259][261] The astronauts spoke before a joint session of Congress on September 16, 1969.[262] This began a 38-day world tour to 22 foreign countries and included visits with the leaders of many countries.[263]

The public's reaction in the Soviet Union was mixed. The Soviet government limited the release of information about the lunar landing, which affected the reaction. A portion of the populace did not give it any attention, and another portion was angered by it.[264]

The first landing was followed by another, precision landing on Apollo 12 in November 1969, within walking distance of the Surveyor 3 spacecraft which landed on April 20, 1967.

In total the Apollo programme involved six crewed Moon landings from 1969 to 1972, and a total of twelve astronauts walked on the surface of the Moon. These were Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16, and Apollo 17.

Post-Apollo NASA: Shifting goals and budget cuts

[edit]NASA had ambitious follow-on human spaceflight plans as it reached its lunar goal but soon discovered it had expended most of its political capital to do so.[265] A victim of its own success, Apollo had achieved its first landing goal with enough spacecraft and Saturn V launchers left for a total of ten lunar landings through Apollo 20, conducting extended-duration missions and transporting the landing crews in Lunar Roving Vehicles on the last five. NASA also planned an Apollo Applications Program (AAP) to develop a longer-duration Earth orbital workshop (later named Skylab) from a spent S-IVB upper stage, to be constructed in orbit using several launches of the smaller Saturn IB launch vehicle.