Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

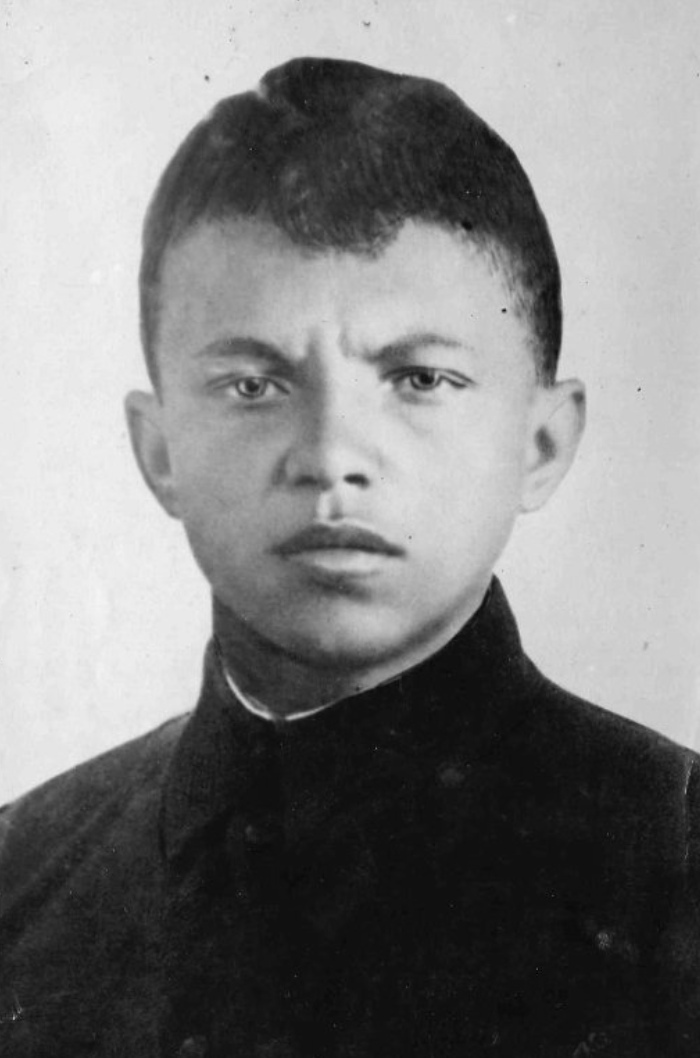

Alexander Matrosov

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Alexander Matveyevich Matrosov (Russian: Алекса́ндр Матве́евич Матро́сов February 5, 1924 – February 27, 1943) was a Soviet infantry soldier during the Second World War, posthumously awarded the title of the Hero of the Soviet Union[2] reportedly for blocking a German machine-gun with his body.[3]

His official Soviet biography states he was born in Yekaterinoslav (now Dnipro). However an evidence emerged that both his name and place of birth were invented by him while he was a street child.[1][failed verification] There are several versions about his origins.[citation needed]

Acts of bravery

[edit]

Matrosov was a private in the 2nd Separate Rifle Battalion of the 91st Independent Siberian Volunteer Brigade, later renamed and the 254th Rifle Regiment and reorganized within the 56th Guards Rifle Division of the Soviet Army. He was armed with a light machine-gun.[4]

On 23 and 24 February 1943, in the battle to recapture village of Chernushki, near Velikiye Luki, currently in Loknyansky District, Pskov Oblast, the Soviet forces struggled to take a German heavy machine-gun, housed within a concrete pillbox, which blocked the route to the village. It had already claimed the lives of many of the Red Army troops. Matrosov crept up to the pillbox and released a burst of rounds into the slot in the pillbox. One round hit a mine inside, and the machine-gun temporarily fell silent. It restarted a few minutes later. At this point Matrosov physically pulled himself up and jammed his body into the slot, wholly blocking the fire at his comrades but clearly at the cost of his own life. This allowed his unit to advance and capture the pillbox and thereafter retake the village.[3]

For his self-sacrifice in battle, Matrosov was posthumously awarded the distinction Hero of the Soviet Union and the Order of Lenin.[5]

Stalin officially renamed his regiment the Matrosov Regiment.[4]

According to one of versions Alexander Matrosov was actually of a Bashkir ethnic minority and his real name Shakiryan Muhammedyanov was Russified.

On 5 January 2023, the day after the monument to Matrosov in his place of birth Dnipro, Ukraine (then Yekaterinoslav, USSR) was dismantled in as part of the derussification and decommunization campaigns following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Mayor of Dnipro Borys Filatov claimed that Matrosov had never been to Yekaterinoslav but he had pretended to be born there so that he looked like a Russian person in Soviet documents.[6][7][1] Filatov also stated that Matrosov was actually of Bashkir ethnicity.[1]

Similar cases

[edit]More than two hundred people were posthumously awarded by the Soviet government for blocking enemy pillboxes with their bodies.

According to Beijing People's Daily, Matrosov's tale also inspired Huang Jiguang, a famous Chinese revolutionary martyr, to perform a similar feat during the Korean War.[8]

During the First Indochina War, in Battle of Dien Bien Phu. A Viet Minh soldier named Phan Đình Giót sacrificed his life to fill the machine gun bunker of the French army to create opportunities for fellow soldiers to advance.

In popular culture

[edit]Matrosov is the main character a number of books and of the 1947 war film, Private Alexander Matrosov (Рядовой Александр Матросов), directed by Leonid Lukov.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Olexei Alexandrov (5 January 2023). "" I'm not at war with the story": Filatov dispelled the myths about the Pushkin tank monument and the Matrosov memorial". Informator (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ Указ Президиума Верховного Совета СССР «О присвоении звания Героя Советского Союза начальствующему и рядовому составу Красной Армии» от 19 июня 1943 года // Ведомости Верховного Совета Союза Советских Социалистических Республик : газета. — 1943. — 23 июня (№ 23 (229)). — С. 3

- ^ a b Матросов Александр Матвеевич. www.warheroes.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ a b Soviet Calendar 1917-1947, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow 1947

- ^ "Матросов Александр Матвеевич". www.warheroes.ru (in Russian).

- ^ Alina Samoilenko (4 January 2023). "In Dnipro, the legendary tank was dismantled on Yavornytsky Avenue". Дніпро Оперативний (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Anton Machula (16 December 2022). "Pushkin and Dubinin monuments were dismantled in Dnipro: who else will be removed from the supplies". Informator (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Matrosov Style Hero, Hung Jiguang (马特洛索夫式的英雄黄继光), Beijing: People's Daily, 1952-12-21, archived from the original on 2012-10-20, retrieved 2012-11-26

External links

[edit]- Image

- A monument to Alexander Matrosov, Moskovsky park of Victory, St. Petersburg

Alexander Matrosov

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Orphanhood and Upbringing

Alexander Matrosov was born on February 5, 1924, with official Soviet records placing his birthplace in Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnipro), Ukrainian SSR, though alternative accounts suggest rural origins near Dulebovo in regions such as Bashkortostan or possibly Kazakhstan, indicating potential fabrication in state biographies to align with proletarian narratives.[2][7] Following the early death of his mother and absence of his father, Matrosov, lacking relatives, ended up on the streets before placement in an orphanage, reportedly first in Ukraine and later transferred to one in Ivanovo Oblast, Russia, around age 6 or 7.[8][5] These institutions, typical of Soviet besprizorniki (street children) facilities in the 1920s-1930s, imposed strict disciplinary measures aimed at rehabilitation through labor and ideological indoctrination, often with minimal emphasis on academic education beyond basic literacy.[8] At approximately age 14, Matrosov was convicted of stealing state property and transferred to a regime corrective labor colony in the Ivanovo region, where youth underwent vocational training under supervised conditions resembling those of adult penal facilities.[9]Pre-Military Employment

In 1939, at the age of 15, Matrosov was directed from the Ivanovo orphanage to Factory No. 9, the Kuibyshev Wagon Repair Plant (now in Samara), for vocational training as a molder under Soviet youth labor programs aimed at integrating orphans into industrial work.[10][11] These programs, part of the factory-professional education (FZO) system, emphasized practical skills in mechanics and manufacturing for adolescents with limited formal schooling.[12] Matrosov briefly complied with the assignment but soon absconded from the plant, relocating to Saratov without authorization. On August 8, 1940, the Saratov People's Court convicted him under Article 192 of the RSFSR Criminal Code for desertion from assigned labor, imposing a sentence of corrective labor.[10][13] Following this, he secured employment as an apprentice locksmith (slayer) in Saratov, continuing in manual labor roles typical of unskilled youth in the pre-war Soviet industrial sector, with no documented promotions, commendations, or further infractions.[14][15] His educational background remained restricted to the incomplete secondary level provided by orphanage schooling, aligning with the systemic constraints on orphans in the 1930s–1940s USSR, where formal academic advancement was often subordinated to immediate workforce integration.[10][12]World War II Service

Enlistment and Initial Training

Alexander Matrosov was conscripted into the Red Army in September 1942 by the Kirovsky District Military Commissariat in Ufa, Bashkir ASSR, at age 18, pursuant to the Soviet Union's compulsory draft of able-bodied males born between 1905 and 1924 to sustain wartime manpower requirements.[16] [17] [18] This mobilization effort, intensified after the 1941 German invasion, prioritized quantity over prior qualifications, drawing from orphanages, factories, and rural areas to replace staggering casualties estimated at over 4 million by mid-1942.[19] Upon induction, Matrosov was directed in October 1942 to the Krasnokholm Infantry School in Chkalov Oblast (present-day Orenburg Oblast) for foundational combat preparation, a common pathway for wartime conscripts lacking prior military experience.[4] [11] Training there focused on essential infantry proficiencies, including handling of the Mosin-Nagant rifle and PPSh-41 submachine gun, basic marksmanship, and simple squad maneuvers such as advancing under fire and occupying positions, often condensed to weeks due to the Red Army's acute shortages of trained personnel.[4] These drills emphasized collective obedience and minimal individual initiative, aligning with doctrinal shifts toward mass assaults following early war defeats. Soviet military instruction invariably incorporated political education, with recruits like Matrosov exposed to lectures on Marxist-Leninist ideology, Stalin's leadership, and the existential threat of fascism, fostering unquestioned loyalty to the Communist Party and state apparatus.[20] Around this time, Matrosov gained admission to the Komsomol (Communist Youth League), a standard vetting process that reinforced ideological conformity as a prerequisite for advancement, though archival records indicate such affiliations were sometimes expedited for propaganda purposes in wartime cohorts.[19] This component subordinated personal agency to regime directives, preparing soldiers for high-casualty operations where survival rates for fresh infantry units hovered below 50% in initial engagements.[4]Assignment to the 254th Rifle Regiment

In November 1942, Alexander Matrosov enlisted in the Red Army and was assigned as a private and submachine gunner to the 2nd Separate Rifle Battalion of the 91st Separate Siberian Volunteer Brigade, named after I. V. Stalin.[4] This formation consisted primarily of volunteers from Siberian regions, reflecting Soviet efforts to bolster infantry units with motivated recruits amid mounting losses on the Eastern Front.[1] The brigade underwent reorganization in early 1943, becoming the 254th Rifle Regiment within the newly formed 56th Guards Rifle Division, which integrated elements of the 91st and other brigades to create an elite assault unit for continued offensives.[4] Deployed to the Northwestern Front near the Pskov region, the unit engaged in operations against the German 3rd Panzer Army's entrenched positions, including remnants of the Velikiye Luki salient following the grueling urban fighting of late 1942, where Soviet forces suffered over 100,000 casualties in failed encirclement attempts.[1] Matrosov's early service involved limited combat exposure prior to February 1943, as the battalion conducted assaults on fortified machine-gun nests amid broader Soviet pushes to relieve pressure on central fronts, facing attrition rates exceeding 50% in some rifle units due to inadequate artillery preparation and winter conditions exacerbating infantry vulnerabilities.[6] Command directives emphasized rapid advances despite these losses, prioritizing momentum over preservation of manpower in the context of Stalin's "Not a Step Back" Order No. 227, which imposed severe penalties for retreats and intensified pressure on forward units.[4]The Incident at Chernushki

Strategic Context of the Battle

In the aftermath of the Soviet victory at Stalingrad in February 1943 and the earlier liberation of Velikiye Luki in January, the North-Western Front initiated local offensives against German Army Group North positions in the Pskov region, aiming to eliminate fortified strongpoints and disrupt enemy supply lines to indirectly alleviate pressure on the besieged Leningrad.[6] These operations, including extensions of the Polar Star effort from mid-February, sought to recapture villages and reduce salients like Demyansk, but were constrained by severe winter weather—deep snow, sub-zero temperatures, and limited visibility—that impeded artillery support and mechanized advances while favoring entrenched defenders.[1] The 254th Rifle Regiment, part of the 56th Rifle Division, was tasked with frontal assaults on heavily fortified German-held villages such as Chernushki, approximately 20 kilometers northwest of Velikiye Luki, where enemy positions included concrete bunkers and machine-gun nests integrated into civilian structures for crossfire coverage.[21] German forces, from units like the 251st Infantry Division remnants, had fortified these points with interlocking fields of fire and anti-infantry obstacles, exploiting the terrain's wooded and swampy features to channel Soviet attackers into kill zones.[6] Soviet tactical doctrine at this stage prioritized rapid penetration of defenses through repeated infantry assaults, often without sufficient preparatory bombardment due to ammunition shortages and weather, leading to casualty rates exceeding 50% in some regiments during such engagements on the North-Western Front.[22] This approach reflected higher command's focus on momentum over preservation of manpower, as divisions were understrength from prior attritional fighting, compelling reliance on massed riflemen to overwhelm machine-gun positions despite predictable high losses from enfilading fire.[6]Sequence of Events Leading to Matrosov's Death

On February 27, 1943, the 2nd Battalion of the Soviet 91st Separate Siberian Volunteer Brigade launched an assault on a German defensive strongpoint located near the villages of Chernushki and Pleten in Pskov Oblast, as part of operations to dislodge enemy forces from entrenched positions. The attacking infantry advanced from a forested area but faced intense machine-gun fire from three bunkers guarding the approaches, which repelled the initial waves and inflicted heavy casualties.[4][6] Specialized groups, including machine gunners and submachine gunners, suppressed two of the bunkers through coordinated fire, but the third emplacement continued operating, preventing further Soviet progress. Privates Alexander Matrosov and Pyotr Ogurtsov, from the same platoon, then crawled under cover toward the firing bunker to attempt its neutralization. Ogurtsov was severely wounded by gunfire during the approach, forcing Matrosov to proceed alone.[6][4] Eyewitness accounts from surviving battalion members report that Matrosov reached grenade-throwing range and lobbed two explosives into the embrasure, briefly halting the machine-gun fire. However, the weapon reactivated as Soviet troops renewed their assault, prompting Matrosov to charge directly at the bunker. He was struck by gunfire while closing on the embrasure; his body fell across it, temporarily obscuring the gun's line of sight and enabling nearby comrades to advance, flank the position, and eliminate the German crew. Variations in reports include whether the grenades detonated effectively or if Matrosov's positioning fully sealed the embrasure versus partially blocking a ventilation outlet, reflecting inconsistencies among platoon-level recollections documented in post-battle debriefs.[6][4]Heroic Narrative and Immediate Recognition

Eyewitness Reports and Initial Accounts

According to accounts from surviving soldiers in the 4th Battalion of the 254th Rifle Regiment, Private Alexander Matrosov, alongside Private Pyotr Ogurtsov, advanced toward a German bunker during the assault on Chernushki village on or around February 27, 1943, after grenades failed to neutralize the machine gun fire impeding the Soviet advance.[23] Ogurtsov was reportedly severely wounded while attempting to suppress the position, leaving Matrosov to approach the embrasure from the flank, throw additional grenades, and then deliberately position his body to block the gun's line of fire, temporarily silencing it and enabling nearby comrades to overrun the position.[23] [24] Battalion records and reports attributed to Captain Afanasyev, the wounded battalion commander, corroborated the deliberate act, describing Matrosov as rising under heavy fire to shield the embrasure with his chest, with the machine gun ceasing fire for approximately 10-20 minutes—long enough for submachine gunners to capture the bunker before enemy reinforcements reactivated firing from adjacent positions.[25] However, contemporaneous soldier testimonies collected in regimental dispatches varied on key details, including the precise timing of the assault—some placing it on February 23 amid ongoing Velikiye Luki operations—and the duration of suppression, with certain accounts indicating the gun was quieted only briefly, insufficient for a full advance without subsequent grenade assaults by others.[26] [27] Internal commendation drafts from the 91st Rifle Brigade, dated within days of February 27, 1943, praised Matrosov's action as a pivotal sacrifice that halted enfilading fire on the platoon, based on platoon leader statements and medical aide observations from the scene, though these preliminary reports omitted granular discrepancies later noted in higher-level reviews.[25] Eyewitnesses, including field medic Galina of the 4th Battalion, emphasized the chaos of snow-covered terrain and close-quarters combat, where Matrosov's body reportedly remained lodged in the embrasure post-mortem, but conflicting loss logs from the 2nd Separate Penal Battalion listed his death definitively on February 27 without specifying the blocking mechanism.[24] [27] These early military dispatches, while unified in ascribing intent to Matrosov's final act, reveal inconsistencies in sequencing that Soviet archives have not fully reconciled, potentially reflecting post-battle reconstructions amid heavy casualties.[26]Posthumous Award of Hero of the Soviet Union

By Uказ of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated June 19, 1943, Alexander Matrosov was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union "for the exemplary performance of combat tasks of the command in the fight against the German invaders, and the manifested courage and heroism."[2][28] This honor, accompanied by the Order of Lenin, recognized his reported act of self-sacrifice in blocking a machine-gun embrasure during the assault on Chernushki on February 27, 1943.[28] In the Stalin-era system of military awards, such distinctions were conferred selectively to exemplify ideological valor, with the Hero title—established in 1934—serving as the highest for wartime feats amid the Red Army's staggering losses exceeding 1.5 million in late 1942 alone.[2] The award's timing, roughly four months after Matrosov's death, underscored the state's imperative to propagate immediate morale-boosting narratives during the grueling Velikiye Luki offensive, where Soviet forces suffered disproportionate casualties against fortified German positions.[2] Joseph Stalin personally noted the deed's inspirational value, reportedly stating it exemplified the "great feat of Border Guard warrior Matrosov," aligning with broader efforts to elevate individual sacrifices as causal drivers of collective victory in official decrees.[2] Matrosov's remains were interred with military honors in a communal grave in Velikiye Luki, Pskov Oblast, formalizing his status as a state-sanctioned symbol of unyielding resolve.[29]Controversies and Skeptical Analyses

Discrepancies in Biographical Details

Official Soviet accounts portrayed Alexander Matrosov as a Russian orphan born on February 5, 1924, in Yekaterinoslav (now Dnipro, Ukraine), whose parents died shortly after his birth, leading to his upbringing in various state institutions before enlisting in the Red Army.[2] However, post-Soviet archival examinations have uncovered conflicting records suggesting alternative origins, including a possible Bashkir ethnic background under the name Shakiryan Yunusovich Mukhamedyanov, with birth in the Bashkir ASSR rather than Ukraine.[30] [31] These discrepancies arise from orphanage and correctional colony documents where Matrosov first adopted a Russified identity, potentially to align with Slavic naming conventions and evade ethnic profiling in Soviet institutions.[6] Matrosov's orphan status contributed to significant documentary gaps, as he frequently transferred between facilities, including an Ivanovo-Detkovsky orphanage in the Ulyanovsk region and a labor colony in Ufa, from which he escaped multiple times between 1939 and 1942.[30] [2] Personnel files from these periods often lack consistent parental details or prior residences, with some records listing fabricated family ties to emphasize a proletarian archetype suitable for wartime propaganda, such as portraying him as a factory worker despite evidence of vagrancy and unauthorized departures from assigned posts like the Kuibyshev wagon repair plant.[30] [32] Post-Soviet reviews of declassified military and civilian archives, including those from the Ulyanovsk and Bashkir regions, have highlighted alterations in enlistment documents, where initial entries under potential aliases were standardized to a singular Russian identity post-1943 to reinforce the heroic narrative.[30] [33] Such revisions, evident in inconsistencies between pre-war orphanage ledgers and Red Army induction papers, indicate efforts to retroactively construct a cohesive biography amid the urgency of symbolizing Soviet resilience, though these changes obscured verifiable ethnic and migratory details.[34]Questions on the Feasibility of the Act

The claimed feat of Matrosov blocking a German machine gun embrasure with his body raises questions about physical feasibility, given the technical specifications of the weapons and fortifications involved. German forces in 1943 commonly employed the MG 34 or MG 42 machine guns, with cyclic rates of fire ranging from 800-900 rounds per minute for the MG 34 and 1,200-1,500 rounds per minute for the MG 42, equivalent to approximately 20-25 rounds per second.[35][36] At such velocities, even a brief obstruction lasting 2-3 seconds—required for comrades to advance under covering fire—would expose the body to 40-75 rounds of 7.92mm ammunition, likely causing rapid disintegration or displacement rather than sustained blockage.[6] Typical WWII German bunker embrasures for machine guns were narrow slits, often 15-30 cm in height and width, designed with sloped or vertical interior walls to deflect grenades and prevent direct sealing by debris or bodies.[37] A human body, with a torso cross-section of roughly 40-50 cm in diameter and mass insufficient to wedge securely against gravity without precise hooking (unlikely under fire), would fail to fully occlude such an opening; bullets impacting the obstructing mass would generate kinetic forces exceeding 1,000 joules per round, propelling tissue fragments and risking ricochet back into the bunker or immediate clearance by gunners using bayonets or pushes.[27] These design features prioritized operational continuity over vulnerability to individual assaults, rendering prolonged blockage improbable without mechanical aids like explosives. Tactically, intentional rushes to seal embrasures contradict defensive engineering principles, where bunkers incorporated multiple firing ports and crew redundancies to maintain suppressive fire. Historical records indicate accidental blockages from piled casualties occurred in static trench warfare, such as early WWI assaults on Belgian forts where accumulated bodies inadvertently provided cover, but deliberate acts were exceedingly rare and often fatal without enabling advances.[38] No verified non-Soviet examples from WWII peer armies document successful intentional body-blocking against high-rate machine guns, suggesting such narratives may stem from exceptional circumstances or post-hoc attribution rather than repeatable tactics.[6]Alternative Explanations and Propaganda Fabrication Claims

Post-Soviet analyses have proposed that Matrosov was fatally wounded while attempting to assault the bunker from its roof, possibly by throwing grenades or firing into a ventilation opening, with his body subsequently falling in a manner that temporarily disrupted the machine gun's operation by obstructing powder gas exhaust rather than directly covering the embrasure.[6] [39] In this reconstruction, the jamming effect would have been incidental, occurring after his death en route to or during the close assault, rather than a deliberate heroic act.[39] Russian skeptics, including contributors to military history publications, contend that the official narrative was fabricated or substantially embellished by Soviet authorities to foster a cult of self-sacrifice amid recurrent command failures that resulted in high-casualty infantry charges against fortified positions.[6] The timing of the publicized feat, aligned with the 25th anniversary of the Red Army on February 23, 1943—despite the reported incident occurring on February 27—suggests deliberate propaganda calibration to maximize morale-boosting impact during a period of stalled offensives.[6] Such stories, replicated in over 200 similar "Matrosov-like" awards during the war, prioritized inspirational symbolism over tactical efficacy, incentivizing unit commanders and witnesses to report exaggerated heroism for personal advancement and to deflect scrutiny from operational shortcomings.[39] The absence of contemporaneous independent verification, with all accounts derived from filtered Soviet military dispatches lacking forensic or neutral corroboration, underscores the narrative's vulnerability to state manipulation.[2] Modern researchers have noted that official biographies sanitized Matrosov's background, omitting details like prior criminal convictions to fit the idealized orphan-soldier archetype, further indicating propagandistic construction over empirical fidelity.[6] [2] These critiques portray the Matrosov legend as a tool to psychologically compel troops toward suicidal tactics in compensation for inadequate artillery preparation and leadership, rather than a veridical event.[6]Propaganda Role and Broader Impact

Symbolism in Soviet Wartime Mobilization

The story of Alexander Matrosov's act of closing an enemy machine-gun embrasure with his body on February 27, 1943, was swiftly elevated by Soviet authorities as a paragon of selfless devotion to the motherland, disseminated through state-controlled newspapers and radio broadcasts in early 1943 to galvanize public support for the war.[6] This propaganda effort sought to enhance recruitment among civilians and reinforce morale among troops by framing extreme personal sacrifice as the epitome of patriotic duty, thereby helping to legitimize the staggering casualties—over 8 million military deaths by war's end—incurred in Stalin's attritional strategy against German forces.[40] Matrosov's narrative embodied the "human shield" archetype of heroism, which resonated with the imperatives of Stalin's Order No. 227, promulgated on July 28, 1942, mandating "not a step back" and instituting blocking detachments to execute retreaters, thus enforcing an advance-or-perish ethos across the Red Army.[41] By glorifying the subordination of individual survival to collective offensive momentum, the symbolism critiqued here promoted a doctrine where soldiers were ideologically primed to emulate fatal self-immolation against fortifications, aligning personal valor with the regime's demand for unrelenting pressure on enemy lines despite prohibitive losses. Post-dissemination, documented patterns emerged of Red Army personnel replicating Matrosov's method by voluntarily covering firing slits with their bodies during assaults, indicating a coerced emulation driven by the pervasive threat of punitive measures for hesitation or withdrawal.[42] This surge in such "voluntary" acts underscored the propaganda's role in internalizing collectivist sacrifice, where deviation risked branding as cowardice under Order 227's framework, thereby sustaining high-casualty operations essential to Soviet wartime mobilization.[43]