Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Iconoclasm

View on Wikipedia

Iconoclasm (from Ancient Greek εἰκών (eikṓn) 'figure, icon' and κλάω (kláō) 'to break')[i] is the belief in the importance of the destruction of icons and other images or monuments, often for religious or political reasons. Those who engage in or support iconoclasm are called iconoclasts, a term that has come to be applied figuratively and more broadly to anyone who challenges "cherished beliefs or venerated institutions on the grounds that they are erroneous or pernicious".[1]

Conversely, one who reveres or venerates religious images is called (by iconoclasts) an iconolater; in a Byzantine context, such a person is called an iconodule or iconophile.[2] Iconoclasm does not generally encompass the destruction of the images of a specific ruler after their death or overthrow, a practice better known as damnatio memoriae.

While iconoclasm may be carried out by adherents of a different religion, it is more commonly the result of sectarian disputes between factions of the same religion. The term originates from the Byzantine Iconoclasm, the struggles between proponents and opponents of religious icons in the Byzantine Empire from 726 to 842 AD. While the enthusiasm for iconoclasm varies among faiths, the practice is more common in religions which oppose idolatry, such as the Abrahamic religions.[3] Outside of the religious context, iconoclasm can refer to movements for widespread destruction in symbols of an ideology or cause, such as the destruction of monarchist symbols during the French Revolution.

Early religious iconoclasm

[edit]Ancient era

[edit]In the Bronze Age, the most significant episode of iconoclasm occurred in Egypt during the Amarna Period, when Akhenaten, based in his new capital of Akhetaten, instituted a significant shift in Egyptian artistic styles alongside a campaign of intolerance towards the traditional gods and a new emphasis on a state monolatristic tradition focused on the god Aten, the Sun disk—many temples and monuments were destroyed as a result:[4][5]

In rebellion against the old religion and the powerful priests of Amun, Akhenaten ordered the eradication of all of Egypt's traditional gods. He sent royal officials to chisel out and destroy every reference to Amun and the names of other deities on tombs, temple walls, and cartouches to instill in the people that the Aten was the one true god.

Public references to Akhenaten were destroyed soon after his death. Comparing the ancient Egyptians with the Israelites, Jan Assmann writes:[6]

For Egypt, the greatest horror was the destruction or abduction of the cult images. In the eyes of the Israelites, the erection of images meant the destruction of divine presence; in the eyes of the Egyptians, this same effect was attained by the destruction of images. In Egypt, iconoclasm was the most terrible religious crime; in Israel, the most terrible religious crime was idolatry. In this respect Osarseph alias Akhenaten, the iconoclast, and the Golden Calf, the paragon of idolatry, correspond to each other inversely, and it is strange that Aaron could so easily avoid the role of the religious criminal. It is more than probable that these traditions evolved under mutual influence. In this respect, Moses and Akhenaten became, after all, closely related.

Judaism

[edit]According to the Hebrew Bible, God instructed the Israelites to "destroy all [the] engraved stones, destroy all [the] molded images, and demolish all [the] high places" of the Canaanites as soon as they entered the Promised Land.[7]

King Hezekiah purged Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem and all figures were also destroyed in the Land of Israel, including the Nehushtan, as recorded in the Second Book of Kings. His reforms were reversed in the reign of his son Manasseh.[8]

Iconoclasm in Christian history

[edit]

Scattered expressions of opposition to the use of images have been reported: the Synod of Elvira appeared to endorse iconoclasm; Canon 36 states: "Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not become objects of worship and adoration."[9][10] A possible translation is also: "There shall be no pictures in the church, lest what is worshipped and adored should be depicted on the walls."[11] The date of this canon is disputed.[12] Proscription ceased after the destruction of pagan temples. However, widespread use of Christian iconography only began as Christianity increasingly spread among Gentiles after the legalization of Christianity by Roman Emperor Constantine (c. 312 AD). During the process of Christianisation under Constantine, Christian groups destroyed the images and sculptures of the Roman Empire's polytheist state religion.

Among early church theologians, iconoclastic tendencies were supported by theologians such as Tertullian,[13][14][15] Clement of Alexandria,[14] Origen,[16][15] Lactantius,[17] Justin Martyr,[15] Eusebius and Epiphanius.[14][18]

Byzantine era

[edit]

The period after the reign of Byzantine Emperor Justinian (527–565) evidently saw a huge increase in the use of images, both in volume and quality, and a gathering aniconic reaction.[citation needed]

One notable change within the Byzantine Empire came in 695, when Justinian II's government added a full-face image of Christ on the obverse of imperial gold coins. The change caused the Caliph Abd al-Malik to stop his earlier adoption of Byzantine coin types. He started a purely Islamic coinage with lettering only.[20] A letter by the Patriarch Germanus, written before 726 to two iconoclast bishops, says that "now whole towns and multitudes of people are in considerable agitation over this matter", but there is little written evidence of the debate.[21]

Government-led iconoclasm began with Byzantine Emperor Leo III, who issued a series of edicts between 726 and 730 against the veneration of images.[22] The religious conflict created political and economic divisions in Byzantine society; iconoclasm was generally supported by the Eastern, poorer, non-Greek peoples of the Empire who had to frequently deal with raids from the new Muslim Empire.[23] On the other hand, the wealthier Greeks of Constantinople and the peoples of the Balkan and Italian provinces strongly opposed iconoclasm.[23]

Pre-Reformation

[edit]Peter of Bruys opposed the usage of religious images,[24] the Strigolniki were also possibly iconoclastic.[25] Claudius of Turin was the bishop of Turin from 817 until his death.[26] He is most noted for teaching iconoclasm.[26]

Reformation era

[edit]

The first iconoclastic wave happened in Wittenberg in the early 1520s under reformers Thomas Müntzer and Andreas Karlstadt. In 1522 Karlstadt published his tract, "Von abtuhung der Bylder". ("On the removal of images"), which added to the growing unrest in Wittenberg.[27] Martin Luther, then concealed under the pen-name of 'Junker Jörg', intervened to calm things down. Luther argued that the mental picturing of Christ when reading the Scriptures was similar in character to artistic renderings of Christ.[28]

In contrast to the Lutherans who favoured certain types of sacred art in their churches and homes,[29][30] the Reformed (Calvinist) leaders, in particular Andreas Karlstadt, Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin, encouraged the removal of religious images by invoking the Decalogue's prohibition of idolatry and the manufacture of graven (sculpted) images of God.[30] As a result, individuals attacked statues and images, most famously in the beeldenstorm across the Low Countries in 1566.

The belief of iconoclasm caused havoc throughout Europe. In 1523, specifically due to the Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli, a vast number of his followers viewed themselves as being involved in a spiritual community that in matters of faith should obey neither the visible Church nor lay authorities. According to Peter George Wallace, "Zwingli's attack on images, at the first debate, triggered iconoclastic incidents in Zürich and the villages under civic jurisdiction that the reformer was unwilling to condone." Due to this action of protest against authority, "Zwingli responded with a carefully reasoned treatise that men could not live in society without laws and constraint".[31]

Significant iconoclastic riots took place in Basel (in 1529), Zürich (1523), Copenhagen (1530), Münster (1534), Geneva (1535), Augsburg (1537), Scotland (1559), Rouen (1560), and Saintes and La Rochelle (1562).[32][33] Calvinist iconoclasm in Europe "provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs" in Germany and "antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox" in the Baltic region.[34]

The Seventeen Provinces (now the Netherlands, Belgium, and parts of Northern France) were disrupted by widespread Calvinist iconoclasm in the summer of 1566.[35]

- Calvinist iconoclasm during the Reformation

-

Destruction of religious images by the Reformed in Zürich, Switzerland, 1524

-

Remains of Calvinist iconoclasm, Clocher Saint-Barthélémy, La Rochelle, France

-

16th-century iconoclasm in the Protestant Reformation. Relief statues in St. Stevenskerk in Nijmegen, Netherlands, were attacked and defaced by Calvinists in the Beeldenstorm.[36][37]

During the Reformation in England, which started during the reign of Henry VIII, and was urged on by reformers such as Hugh Latimer and Thomas Cranmer, limited official action was taken against religious images in churches in the late 1530s. Henry's young son, Edward VI, came to the throne in 1547 and, under Cranmer's guidance, issued injunctions for religious reforms in the same year and in 1549 the Putting away of Books and Images Act.[41]

During the English Civil War, the Parliamentarians reorganised the administration of East Anglia into the Eastern Association of counties. This covered some of the wealthiest counties in England, which in turn financed a substantial and significant military force. After Earl of Manchester was appointed the commanding officer of these forces, in turn he appointed Smasher Dowsing as Provost Marshal, with a warrant to demolish religious images which were considered to be superstitious or linked with popism.[42] Bishop Joseph Hall of Norwich described the events of 1643 when troops and citizens, encouraged by a Parliamentary ordinance against superstition and idolatry, behaved thus:

Lord what work was here! What clattering of glasses! What beating down of walls! What tearing up of monuments! What pulling down of seats! What wresting out of irons and brass from the windows! What defacing of arms! What demolishing of curious stonework! What tooting and piping upon organ pipes! And what a hideous triumph in the market-place before all the country, when all the mangled organ pipes, vestments, both copes and surplices, together with the leaden cross which had newly been sawn down from the Green-yard pulpit and the service-books and singing books that could be carried to the fire in the public market-place were heaped together.

Protestant Christianity was not uniformly hostile to the use of religious images. Martin Luther taught the "importance of images as tools for instruction and aids to devotion",[43] stating: "If it is not a sin but good to have the image of Christ in my heart, why should it be a sin to have it in my eyes?"[44] Lutheran churches retained ornate church interiors with a prominent crucifix, reflecting their high view of the real presence of Christ in Eucharist.[45][29] As such, "Lutheran worship became a complex ritual choreography set in a richly furnished church interior."[45] For Lutherans, "the Reformation renewed rather than removed the religious image".[46]

Lutheran scholar Jeremiah Ohl writes:[47]: 88–89

Zwingli and others for the sake of saving the Word rejected all plastic art; Luther, with an equal concern for the Word, but far more conservative, would have all the arts to be the servants of the Gospel. "I am not of the opinion" said [Luther], "that through the Gospel all the arts should be banished and driven away, as some zealots want to make us believe; but I wish to see them all, especially music, in the service of Him Who gave and created them." Again he says: "I have myself heard those who oppose pictures, read from my German Bible.... But this contains many pictures of God, of the angels, of men, and of animals, especially in the Revelation of St. John, in the books of Moses, and in the book of Joshua. We therefore kindly beg these fanatics to permit us also to paint these pictures on the wall that they may be remembered and better understood, inasmuch as they can harm as little on the walls as in books. Would to God that I could persuade those who can afford it to paint the whole Bible on their houses, inside and outside, so that all might see; this would indeed be a Christian work. For I am convinced that it is God's will that we should hear and learn what He has done, especially what Christ suffered. But when I hear these things and meditate upon them, I find it impossible not to picture them in my heart. Whether I want to or not, when I hear, of Christ, a human form hanging upon a cross rises up in my heart: just as I see my natural face reflected when I look into water. Now if it is not sinful for me to have Christ's picture in my heart, why should it be sinful to have it before my eyes?

The Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, who had pragmatic reasons to support the Dutch Revolt (the rebels, like himself, were fighting against Spain) also completely approved of their act of "destroying idols", which accorded well with Muslim teachings.[48][49]

16th century Protestant iconoclasm had various effects on visual arts: it encouraged the development of art with violent images such as martyrdoms, of pieces whose subject was the dangers of idolatry, or art stripped of objects with overt Catholic symbolism: the still life, landscape and genre paintings.[50]: 44, 25, 40

Other instances

[edit]In Japan during the early modern age, the spread of Catholicism also involved the repulsion of non-Christian religious structures, including Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines and figures. At times of conflict with rivals or some time after the conversion of several daimyos, Christian converts would often destroy Buddhist and Shinto religious structures.[51]

Many of the moai of Easter Island were toppled during the 18th century in the iconoclasm of civil wars before any European encounter.[52] Other instances of iconoclasm may have occurred throughout Eastern Polynesia during its conversion to Christianity in the 19th century.[53]

After the Second Vatican Council in the late 20th century, some Roman Catholic parish churches discarded much of their traditional imagery and art which critics call iconoclasm.[54]

Muslim iconoclasm

[edit]

Islam has a strong tradition of forbidding the depiction of figures, especially religious figures,[3] with some Sunnis forbidding it entirely. In the history of Islam, the act of removing idols from the Ka'ba in Mecca has great symbolic and historic importance for all believers.

In general, Muslim societies have avoided the depiction of living beings (both animals and humans) within such sacred spaces as mosques and madrasahs. This ban on figural representation is not based on the Qur'an, instead, it is based on traditions which are described within the Hadith. The prohibition of figuration has not always been extended to the secular sphere, and a robust tradition of figural representation exists within Muslim art.[55] However, Western authors have tended to perceive "a long, culturally determined, and unchanging tradition of violent iconoclastic acts" within Islamic society.[55]

Early Islam in Arabia

[edit]The first act of Muslim iconoclasm dates to the beginning of Islam, in 630, when the various statues of Arabian deities housed in the Kaaba in Mecca were destroyed. There is a tradition that Muhammad spared a fresco of Mary and Jesus.[56] This act was intended to bring an end to the idolatry which, in the Muslim view, characterized Jahiliyyah.

The destruction of the idols of Mecca did not, however, determine the treatment of other religious communities living under Muslim rule after the expansion of the caliphate. Most Christians under Muslim rule, for example, continued to produce icons and to decorate their churches as they wished. A major exception to this pattern of tolerance in early Islamic history was the "Edict of Yazīd", issued by the Umayyad caliph Yazīd II in 722–723.[57] This edict ordered the destruction of crosses and Christian images within the territory of the caliphate. Researchers have discovered evidence that the order was followed, particularly in present-day Jordan, where archaeological evidence shows the removal of images from the mosaic floors of some, although not all, of the churches that stood at this time. But Yazīd's iconoclastic policies were not continued by his successors, and Christian communities of the Levant continued to make icons without significant interruption from the sixth century to the ninth.[58]

Egypt

[edit]

Al-Maqrīzī, writing in the 15th century, attributes the missing nose on the Great Sphinx of Giza to iconoclasm by Muhammad Sa'im al-Dahr, a Sufi Muslim in the mid-1300s. He was reportedly outraged by local Muslims making offerings to the Great Sphinx in the hope of controlling the flood cycle, and he was later executed for vandalism. However, whether this was actually the cause of the missing nose has been debated by historians.[59] Mark Lehner, having performed an archaeological study, concluded that it was broken with instruments at an earlier unknown time between the 3rd and 10th centuries.[60]

Ottoman conquests

[edit]Certain conquering Muslim armies have used local temples or houses of worship as mosques. An example is Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), which was converted into a mosque in 1453. Most icons were desecrated and the rest were covered with plaster. In 1934 the government of Turkey decided to convert the Hagia Sophia into a museum and the restoration of the mosaics was undertaken by the American Byzantine Institute beginning in 1932.

Contemporary events

[edit]Certain Muslim denominations continue to pursue iconoclastic agendas. There has been much controversy within Islam over the recent and apparently on-going destruction of historic sites by Saudi Arabian authorities, prompted by the fear they could become the subject of "idolatry".[61][62]

A recent act of iconoclasm was the 2001 destruction of the giant Buddhas of Bamyan by the then-Taliban government of Afghanistan.[63] The act generated worldwide protests and was not supported by other Muslim governments and organizations. It was widely perceived in the Western media as a result of the Muslim prohibition against figural decoration. Such an account overlooks "the coexistence between the Buddhas and the Muslim population that marveled at them for over a millennium" before their destruction.[55] According to art historian F. B. Flood, analysis of the Taliban's statements regarding the Buddhas suggest that their destruction was motivated more by political than by theological concerns.[55] Taliban spokesmen have given many different explanations of the motives for the destruction.

During the Tuareg rebellion of 2012, the radical Islamist militia Ansar Dine destroyed various Sufi shrines from the 15th and 16th centuries in the city of Timbuktu, Mali.[64] In 2016, the International Criminal Court (ICC) sentenced Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi, a former member of Ansar Dine, to nine years in prison for this destruction of cultural world heritage. This was the first time that the ICC convicted a person for such a crime.[65]

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant carried out iconoclastic attacks such as the destruction of Shia mosques and shrines. Notable incidents include blowing up the Mosque of the Prophet Yunus (Jonah)[66] and destroying the Shrine to Seth in Mosul.[67]

Iconoclasm in India

[edit]During Hindu-Buddhist era

[edit]In early Medieval India, there were numerous recorded instances of temple desecration by Indian kings against rival Indian kingdoms, which involved conflicts between devotees of different Hindu deities, as well as conflicts between Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains.[68][69][page needed][70][page needed]

During the Muslim conquest of Sindh

[edit]Records from the campaign recorded in the Chach Nama record the destruction of temples during the early 8th century when the Umayyad governor of Damascus, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf,[71] mobilized an expedition of 6000 cavalry under Muhammad bin Qasim in 712.

Historian Upendra Thakur records the persecution of Hindus and Buddhists:

Muhammad triumphantly marched into the country, conquering Debal, Sehwan, Nerun, Brahmanadabad, Alor and Multan one after the other in quick succession, and in less than a year and a half, the far-flung Hindu kingdom was crushed ... There was a fearful outbreak of religious bigotry in several places and temples were wantonly desecrated. At Debal, the Nairun and Aror temples were demolished and converted into mosques.[72]

- Iconoclasm during the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent

-

The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 AD.[73] The present temple was reconstructed in Chalukyan style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[74][75]

-

The Kashi Vishwanath Temple was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic invaders such as Qutb al-Din Aibak.

-

Ruins of the Martand Sun Temple. The temple was destroyed on the orders of Muslim Sultan Sikandar Butshikan in the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year.

-

The armies of Delhi Sultanate led by Muslim Commander Malik Kafur plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables.

-

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[69]

-

Rani Ki Vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[69]

-

Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh at Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was destroyed by Alauddin Khalji.

-

Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[76]

The Somnath temple and Mahmud of Ghazni

[edit]Perhaps the most notorious episode of iconoclasm in India was Mahmud of Ghazni's attack on the Somnath Temple from across the Thar Desert.[77][78][79] In 1026 during the reign of Bhima I, the prominent Turkic-Muslim ruler Mahmud of Ghazni raided Gujarat, plundering the Somnath Temple and breaking its jyotirlinga despite pleas by Brahmins not to break it. He took away a booty of 20 million dinars.[80][79]: 39 The attack may have been inspired by the belief that an idol of the goddess Manat had been secretly transferred to the temple.[81] According to the Ghaznavid court-poet Farrukhi Sistani, who claimed to have accompanied Mahmud on his raid, Somnat (as rendered in Persian) was a garbled version of su-manat referring to the goddess Manat. According to him, as well as a later Ghaznavid historian Abu Sa'id Gardezi, the images of the other goddesses were destroyed in Arabia but the one of Manat was secretly sent away to Kathiawar (in modern Gujarat) for safekeeping. Since the idol of Manat was an aniconic image of black stone, it could have been easily confused with a lingam at Somnath. Mahmud is said to have broken the idol and taken away parts of it as loot and placed so that people would walk on it. In his letters to the Caliphate, Mahmud exaggerated the size, wealth and religious significance of the Somnath temple, receiving grandiose titles from the Caliph in return.[80]: 45–51

The wooden structure was replaced by Kumarapala (r. 1143–72), who rebuilt the temple out of stone.[82]

From the Mamluk dynasty onward

[edit]Historical records which were compiled by the Muslim historian Maulana Hakim Saiyid Abdul Hai attest to the religious violence which occurred during the Mamluk dynasty under Qutb-ud-din Aybak. The first mosque built in Delhi, the "Quwwat al-Islam" was built with demolished parts of 20 Hindu and Jain temples.[83][84] This pattern of iconoclasm was common during his reign.[85]

During the Delhi Sultanate, a Muslim army led by Malik Kafur, a general of Alauddin Khalji, pursued four violent campaigns into south India, between 1309 and 1311, against the Hindu kingdoms of Devgiri (Maharashtra), Warangal (Telangana), Dwarasamudra (Karnataka) and Madurai (Tamil Nadu). Many Temples were plundered; Hoysaleswara Temple and others were ruthlessly destroyed.[86][87]

In Kashmir, Sikandar Shah Miri (1389–1413) began expanding, and unleashed religious violence that earned him the name but-shikan, or 'idol-breaker'.[88] He earned this sobriquet because of the sheer scale of desecration and destruction of Hindu and Buddhist temples, shrines, ashrams, hermitages, and other holy places in what is now known as Kashmir and its neighboring territories. Firishta states: "After the emigration of the Brahmins, Sikundur ordered all the temples in Kashmeer to be thrown down."[89] He destroyed vast majority of Hindu and Buddhist temples in his reach in Kashmir region (north and northwest India).[90]

A regional tradition, along with the Hindu text Madala Panji, states that Kalapahar attacked and damaged the Konark Sun Temple in 1568, as well as many others in Orissa.[91][92]

Some of the most dramatic cases of iconoclasm by Muslims are found in parts of India where Hindu and Buddhist temples were razed and mosques erected in their place. Aurangzeb, the 6th Mughal Emperor, destroyed the famous Hindu temples at Varanasi and Mathura, turning back on his ancestor Akbar's policy of religious freedom and establishing Sharia across his empire.[93]

During the Goa Inquisition

[edit]Exact data on the nature and number of Hindu temples destroyed by the Christian missionaries and Portuguese government are unavailable. Some 160 temples were allegedly razed to the ground in Tiswadi (Ilhas de Goa) by 1566. Between 1566 and 1567, a campaign by Franciscan missionaries destroyed another 300 Hindu temples in Bardez (North Goa). In Salcete (South Goa), approximately another 300 Hindu temples were destroyed by the Christian officials of the Inquisition. Numerous Hindu temples were destroyed elsewhere at Assolna and Cuncolim by Portuguese authorities.[94] A 1569 royal letter in Portuguese archives records that all Hindu temples in its colonies in India had been burnt and razed to the ground.[95] The English traveller Sir Thomas Herbert, 1st Baronet who visited Goa in the 1600s writes:

... as also the ruins of 200 Idol Temples which the Vice-Roy Antonio Norogna totally demolisht, that no memory might remain, or monuments continue, of such gross Idolatry. For not only there, but at Salsette also were two Temples or places of prophane Worship; one of them (by incredible toil cut out of the hard Rock) was divided into three Iles or Galleries, in which were figured many of their deformed Pagotha's, and of which an Indian (if to be credited) reports that there were in that Temple 300 of those narrow Galleries, and the Idols so exceeding ugly as would affright an European Spectator; nevertheless this was a celebrated place, and so abundantly frequented by Idolaters, as induced the Portuguise in zeal with a considerable force to master the Town and to demolish the Temples, breaking in pieces all that monstrous brood of mishapen Pagods. In Goa nothing is more observable now than the fortifications, the Vice-Roy and Arch-bishops Palaces, and the Churches. ...[96]

In modern India

[edit]B. R. Ambedkar and his supporters on 25 December 1927 in the Mahad Satyagraha strongly criticised, condemned and then burned copies of Manusmriti on a pyre in a specially dug pit. Manusmriti, one of the sacred Hindu texts, is the religious basis of casteist laws and values of Hinduism and hence was/is the reason of social and economic plight of millions of untouchables and lower caste Hindus. Ambedkarites continue to observe 25 December as "Manusmriti Dahan Divas" (Manusmriti Burning Day) and burn copies of Manusmriti on this day.[citation needed]

The most high-profile case of iconoclasm in independent India was in 1992. A Hindu mob, led by the Vishva Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal, destroyed the 430-year-old Islamic Babri Masjid in Ayodhya which is claimed to have been built upon a previous Hindu temple.[97][98]

Iconoclasm in East Asia

[edit]China

[edit]There have been a number of anti-Buddhist campaigns in Chinese history that led to the destruction of Buddhist temples and images. One of the most notable of these campaigns was the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution of the Tang dynasty.

During and after the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, there was widespread destruction of religious and secular images in China.

During the Northern Expedition in Guangxi in 1926, Kuomintang General Bai Chongxi led his troops in destroying Buddhist temples and smashing Buddhist images, turning the temples into schools and Kuomintang party headquarters.[99] It was reported that almost all of the viharas in Guangxi were destroyed and the monks were removed.[100] Bai also led a wave of anti-foreignism in Guangxi, attacking Americans, Europeans, and other foreigners, and generally making the province unsafe for foreigners and missionaries. Westerners fled from the province and some Chinese Christians were also attacked as imperialist agents.[101] The three goals of the movement were anti-foreignism, anti-imperialism and anti-religion. Bai led the anti-religious movement against superstition. Huang Shaohong, also a Kuomintang member of the New Guangxi clique, supported Bai's campaign. The anti-religious campaign was agreed upon by all Guangxi Kuomintang members.[101]

There was extensive destruction of religious and secular imagery in Tibet after it was invaded and occupied by China.[102]

Many religious and secular images were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976, ostensibly because they were a holdover from China's traditional past (which the Communist regime led by Mao Zedong reviled). The Cultural Revolution included widespread destruction of historic artworks in public places and private collections, whether religious or secular. Objects in state museums were mostly left intact.

South Korea

[edit]According to an article in Buddhist-Christian Studies:[103]

Over the course of the last decade [1990s] a fairly large number of Buddhist temples in South Korea have been destroyed or damaged by fire by Christian fundamentalists. More recently, Buddhist statues have been identified as idols, and attacked and decapitated in the name of Jesus. Arrests are hard to effect, as the arsonists and vandals work by stealth of night.

Angkor

[edit]Beginning c. 1243 AD with the death of Indravarman II, the Khmer Empire went through a period of iconoclasm. At the beginning of the reign of the next king, Jayavarman VIII, the kingdom went back to Hinduism and the worship of Shiva. Many of the Buddhist images were destroyed by Jayavarman VIII, who reestablished previously Hindu shrines that had been converted to Buddhism by his predecessor. Carvings of the Buddha at temples such as Preah Khan were destroyed, and during this period the Bayon Temple was made a temple to Shiva, with the central 3.6-meter-tall (12 ft) statue of the Buddha cast to the bottom of a nearby well.[104]

Political iconoclasm

[edit]Damnatio memoriae

[edit]Revolutions and changes of regime, whether through uprising of the local population, foreign invasion, or a combination of both, are often accompanied by the public destruction of statues and monuments identified with the previous regime. This may also be known as damnatio memoriae, the ancient Roman practice of official obliteration of the memory of a specific individual. Stricter definitions of "iconoclasm" exclude both types of action, reserving the term for religious or more widely cultural destruction.[citation needed] In many cases, such as Revolutionary Russia or Ancient Egypt, this distinction can be hard to make.

Among Roman emperors and other political figures subject to decrees of damnatio memoriae were Sejanus, Publius Septimius Geta, and Domitian. Several Emperors, such as Domitian and Commodus had during their reigns erected numerous statues of themselves, which were pulled down and destroyed when they were overthrown.

The perception of damnatio memoriae in the Classical world as an act of erasing memory has been challenged by scholars who have argued that it "did not negate historical traces, but created gestures which served to dishonor the record of the person and so, in an oblique way, to confirm memory",[105] and was in effect a spectacular display of "pantomime forgetfulness".[106] Examining cases of political monument destruction in modern Irish history, Guy Beiner has demonstrated that iconoclastic vandalism often entails subtle expressions of ambiguous remembrance and that, rather than effacing memory, such acts of de-commemorating effectively preserve memory in obscure forms.[107][108][109]

During the French Revolution

[edit]Throughout the radical phase of the French Revolution, iconoclasm was supported by members of the government as well as the citizenry. Numerous monuments, religious works, and other historically significant pieces were destroyed in an attempt to eradicate any memory of the Old Regime. A statue of King Louis XV in the Paris square which until then bore his name, was pulled down and destroyed. This was a prelude to the guillotining of his successor Louis XVI in the same site, renamed "Place de la Révolution" (at present Place de la Concorde).[110] Later that year, the bodies of many French kings were exhumed from the Basilica of Saint-Denis and dumped in a mass grave.[111]

Some episodes of iconoclasm were carried out spontaneously by crowds of citizens, including the destruction of statues of kings during the insurrection of 10 August 1792 in Paris.[112] Some were directly sanctioned by the Republican government, including the Saint-Denis exhumations.[111] Nonetheless, the Republican government also took steps to preserve historic artworks,[113] notably by founding the Louvre museum to house and display the former royal art collection. This allowed the physical objects and national heritage to be preserved while stripping them of their association with the monarchy.[114][115][116] Alexandre Lenoir saved many royal monuments by diverting them to preservation in a museum.[117]

The statue of Napoleon on the column at Place Vendôme, Paris was also the target of iconoclasm several times: destroyed after the Bourbon Restoration, restored by Louis-Philippe, destroyed during the Paris Commune and restored by Adolphe Thiers.

After Napoleon conquered the Italian city of Pavia, local Pavia Jacobins destroyed the Regisole, a bronze classical equestrian monument dating back to Classical times. The Jacobins considered it a symbol of Royal authority, but it had been a prominent Pavia landmark for nearly a thousand years and its destruction aroused much indignation and precipitated a revolt by inhabitants of Pavia against the French, which was quelled by Napoleon after a furious urban fight.

Other examples

[edit]

Other examples of political destruction of images include:

- There have been several cases of removing symbols of past rulers in Malta's history. Many Hospitaller coats of arms on buildings were defaced during the French occupation of Malta in 1798–1800; a few of these were subsequently replaced by British coats of arms in the early 19th century.[118] Some British symbols were also removed by the government after Malta became a republic in 1974. These include royal cyphers being ground off from post boxes,[119] and British coats of arms such as that on the Main Guard building being temporarily obscured (but not destroyed).[120]

- With the entry of the Ottoman Empire to the First World War, the Ottoman Army destroyed the Russian victory monument erected in San Stefano (the modern Yeşilköy quarter of Istanbul, Turkey) to commemorate the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. The demolition was filmed by former army officer Fuat Uzkınay, producing Ayastefanos'taki Rus Abidesinin Yıkılışı—the oldest known Turkish-made film.

- In the late 18th century, French revolutionaries known as the sans-culottes sacked Brussels' Grand-Place, destroying statues of nobility and symbols of Christianity.[121][122] In the 19th century, the place was renovated and many new statues added. In 1911, a marble commemoration for the Spanish freethinker and educator Francisco Ferrer, executed two years earlier and widely considered a martyr, was erected in the Grand-Place. The statue depicted a nude man holding the Torch of Enlightenment. The Imperial German military, which occupied Belgium during the First World War, disliked the monument and destroyed it in 1915. It was restored in 1926 by the International Free Thought Movement.[123]

- In 1942, the pro-Nazi Vichy Government of France took down and melted Clothilde Roch's statue of the 16th-century dissident intellectual Michael Servetus, who had been burned at the stake in Geneva at the instigation of Calvin. The Vichy authorities disliked the statue, as it was a celebration of freedom of conscience. In 1960, having found the original molds, the municipality of Annemasse had it recast and returned the statue to its previous place.[124]

- A sculpture of the head of Spanish intellectual Miguel de Unamuno by Victorio Macho was installed in the City Hall of Bilbao, Spain. It was withdrawn in 1936 when Unamuno showed temporary support for the Nationalist side. During the Spanish Civil War, it was thrown into the estuary. It was later recovered. In 1984 the head was installed in Plaza Unamuno. In 1999, it was again thrown into the estuary after a political meeting of Euskal Herritarrok. It was substituted by a copy in 2000 after the original was located in the water.[125][126][127]

- The Battle of Baghdad and the regime of Saddam Hussein symbolically ended with the Firdos Square statue destruction, a U.S. military-staged event on 9 April 2003 where a prominent statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down. Subsequently, statues and murals of Saddam Hussein all over Iraq were destroyed by US occupation forces as well as Iraqi citizens.[128]

- In 2016, paintings from the University of Cape Town, South Africa, were burned in student protests as symbols of colonialism.[129]

- In November 2019, a statue of Swedish footballer Zlatan Ibrahimović in Malmö, Sweden, was vandalized by Malmö FF supporters after he announced he had become part-owner of Swedish rivals Hammarby. White paint was sprayed on it; threats and hateful messages towards Zlatan were written on the statue, and it was burned.[130][131] In a second attack the nose was sawed off and the statue was sprinkled with chrome paint.[132] On 5 January 2020 it was finally toppled.[133]

- On 7 June 2020, during the George Floyd protests,[134] a statue of merchant and trans-Atlantic slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol, UK, was pulled down by demonstrators who then jumped on it.[135] They daubed it in red and blue paint, and one protester placed his knee on the statue's neck to allude to Floyd's murder by a white policeman who knelt on Floyd's neck for over nine minutes.[134][136] The statue was then rolled down Anchor Road and pushed into Bristol Harbour.[135][137][138]

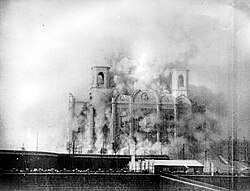

In the Soviet Union

[edit]

During and after the October Revolution, widespread destruction of religious and secular imagery in Russia took place, as well as the destruction of imagery related to the Imperial family. The Revolution was accompanied by destruction of monuments of tsars, as well as the destruction of imperial eagles at various locations throughout Russia. According to Christopher Wharton:[139]

In front of a Moscow Cathedral, crowds cheered as the enormous statue of Tsar Alexander III was bound with ropes and gradually beaten to the ground. After a considerable amount of time, the statue was decapitated and its remaining parts were broken into rubble.

The Soviet Union actively destroyed religious sites, including Russian Orthodox churches and Jewish cemeteries, in order to discourage religious practice and curb the activities of religious groups.

During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and during the Revolutions of 1989, protesters often attacked and took down sculptures and images of Joseph Stalin, such as the Stalin Monument in Budapest.[140]

The fall of Communism in 1989–1991 was also followed by the destruction or removal of statues of Vladimir Lenin and other Communist leaders in the former Soviet Union and in other Eastern Bloc countries. Particularly well-known was the destruction of "Iron Felix", the statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky outside the KGB's headquarters. Another statue of Dzerzhinsky was destroyed in a Warsaw square that was named after him during communist rule, but which is now called Bank Square.

In the United States

[edit]

During the American Revolution, the Sons of Liberty pulled down and destroyed the gilded lead statue of George III of the United Kingdom on Bowling Green (New York City), melting it down to be recast as ammunition.[141][142][143] Sometimes relatively intact monuments are moved to a collected display in a less prominent place, as in India and also post-Communist countries.

In August 2017, a statue of a Confederate soldier dedicated to "the boys who wore the gray" was pulled down from its pedestal in front of Durham County Courthouse in North Carolina by protesters. This followed the events at the 2017 Unite the Right rally in response to growing calls to remove Confederate monuments and memorials across the U.S.[144][145][146][147]

2020 demonstrations

[edit]During the George Floyd protests of 2020, demonstrators pulled down dozens of statues which they considered symbols of the Confederacy, slavery, segregation, or racism, including the statue of Williams Carter Wickham in Richmond, Virginia.[148][149]

Further demonstrations in the wake of the George Floyd protests have resulted in the removal of:[150]

- the John Breckenridge Castleman monument in Louisville, Kentucky;

- plaques in Jacksonville, Florida's Hemming Park (renamed in 1899 in honor of Civil War veteran Charles C. Hemming), which were in remembrance of deceased Confederate soldiers;

- the monumental obelisk of the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument and a statue of Charles Linn in Linn Park, Birmingham, Alabama;

- a statue of Junípero Serra in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco;[151]

- a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in Montgomery, Alabama;

- the monument to Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia;[152]

- the Appomattox statue in Alexandria, Virginia, leaving the monument's base empty but intact.

Multiple statues of early European explorers and founders were also vandalized, including those of Christopher Columbus, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson.[153][154]

- Christopher Columbus was removed in Virginia, Minnesota, Chicago and beheaded in Boston MA.[153]

- George Washington statue was toppled in Portland, Oregon.[154]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ From Ancient Greek: εἰκών + κλάω, romanized: eikṓn + kláō, lit. 'image-breaking'. Iconoclasm may also be considered as a back-formation from iconoclast (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία (eikonoklasia).

References

[edit]- ^ "Iconoclast, 2", Oxford English Dictionary; see also "Iconoclasm" and "Iconoclastic".

- ^ "icono-, comb. form". OED Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Crone, Patricia. 2005. "Islam, Judeo-Christianity and Byzantine Iconoclasm". Archived 2018-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. pp. 59–96 in From Kavād to al-Ghazālī: Religion, Law and Political Thought in the Near East, c. 600–1100, (Variorum). Ashgate Publishing.

- ^ H. James Birx, Encyclopedia of Anthropology, Vol. 1, Sage Publications, US, 2006, p. 802

- ^ "Akhenaten". Encyclopedia of World Biography. 20 June 2020. via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Assmann, Jan. 2014. From Akhenaten to Moses: Ancient Egypt and Religious Change. American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 977-416-631-0. p. 76.

- ^ Bible, Numbers 33:52 and similarly Bible, Deuteronomy 7:5

- ^ "2 Kings 21 / Hebrew–English Bible / Mechon-Mamre". mechon-mamre.org. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ Elvira canons, Cua, archived from the original on 2012-07-16,

Placuit picturas in ecclesia esse non debere, ne quod colitur et adoratur in parietibus depingatur

. - ^ The Catholic Encyclopedia,

This canon has often been urged against the veneration of images as practised in the Catholic Church. Binterim, De Rossi, and Hefele interpret this prohibition as directed against the use of images in overground churches only, lest the pagans should caricature sacred scenes and ideas; Von Funk, Termel, and Henri Leclercq opine that the council did not pronounce as to the liceity or non-liceity of the use of images, but as an administrative measure simply forbade them, lest new and weak converts from paganism should incur thereby any danger of relapse into idolatry, or be scandalized by certain superstitious excesses in no way approved by the ecclesiastical authority.

- ^ Grigg, Robert (1976-12-01). "Aniconic Worship and the Apologetic Tradition: A Note on Canon 36 of the Council of Elvira". Church History. 45 (4): 428–433. doi:10.2307/3164346. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3164346. S2CID 162369274.

- ^ "The Council of Elvira, ca. 306". Archived from the original on 2016-02-29. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ Dimmick, Jeremy; Simpson, James; Zeeman, Nicolette (2002). Images, Idolatry, and Iconoclasm in Late Medieval England: Textuality and the Visual Image. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-154196-4.

- ^ a b c Jensen, Robin Margaret (2013). Understanding Early Christian Art. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-95170-2.

- ^ a b c Strezova, Anita (2013-11-25). "Overview on Iconophile and Iconoclastic Attitudes toward Images in Early Christianity and Late Antiquity". Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies.

- ^ O'Gorman, Ned (2016). The Iconoclastic Imagination: Image, Catastrophe, and Economy in America from the Kennedy Assassination to September 11. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31023-7.

- ^ Humphreys, Mike (2021). A Companion to Byzantine Iconoclasm. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-46200-7.

- ^ Kitzinger, 92–93, 92 quoted

- ^ "Byzantine iconoclasm". Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Cormack, Robin. 1985. Writing in Gold, Byzantine Society and its Icons. London: George Philip. ISBN 0-540-01085-5.

- ^ Mango, Cyril. 1977. "Historical Introduction". pp. 2–3 in Iconoclasm, edited by Bryer & Herrin. Birmingham: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Birmingham. ISBN 0-7044-0226-2.

- ^ Treadgold, Warren. 1997. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. pp. 350, 352–353.

- ^ a b Mango, Cyril. 2002. The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kim, Elijah Jong Fil (2012). The Rise of the Global South: The Decline of Western Christendom and the Rise of Majority World Christianity. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61097-970-2.

- ^ Michalski, Sergiusz (2013). Reformation and the Visual Arts: The Protestant Image Question in Western and Eastern Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-92102-7.

- ^ a b F. L. Cross; E. A. Livingstone, eds. (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.). US: Oxford University Press. p. 359. ISBN 0-19-211655-X.

- ^ Lindberg, Carter (2021). The European reformations (3rd ed.). Chichester, United Kingdom Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 84–91. ISBN 978-1-119-64081-3.

- ^ Dorner, Isaak August. 1871. History of Protestant Theology. Edinburgh. p. 146.

- ^ a b Lamport, Mark A. (2017). Encyclopedia of Martin Luther and the Reformation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 978-1442271593.

Lutherans continued to worship in pre-Reformation churches, generally with few alterations to the interior. It has even been suggested that in Germany to this day one finds more ancient Marian altarpieces in Lutheran than in Catholic churches. Thus in Germany and in Scandinavia many pieces of medieval art and architecture survived. Joseph Koerner has noted that Lutherans, seeing themselves in the tradition of the ancient, apostolic church, sought to defend as well as reform the use of images. "An empty, white-washed church proclaimed a wholly spiritualized cult, at odds with Luther's doctrine of Christ's real presence in the sacraments" (Koerner 2004, 58). In fact, in the 16th century some of the strongest opposition to destruction of images came not from Catholics but from Lutherans against Calvinists: "You black Calvinist, you give permission to smash our pictures and hack our crosses; we are going to smash you and your Calvinist priests in return" (Koerner 2004, 58). Works of art continued to be displayed in Lutheran churches, often including an imposing large crucifix in the sanctuary, a clear reference to Luther's theologia crucis. ... In contrast, Reformed (Calvinist) churches are strikingly different. Usually unadorned and somewhat lacking in aesthetic appeal, pictures, sculptures, and ornate altar-pieces are largely absent; there are few or no candles; and crucifixes or crosses are also mostly absent.

- ^ a b Félix, Steven (2015). Pentecostal Aesthetics: Theological Reflections in a Pentecostal Philosophy of Art and Esthetics. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-9004291621.

Luther's view was that biblical images could be used as teaching aids, and thus had didactic value. Hence Luther stood against the destruction of images whereas several other reformers (Karlstadt, Zwingli, Calvin) promoted these actions. In the following passage, Luther harshly rebukes Karlstadt on his stance on iconoclasm and his disorderly conduct in reform.

- ^ Wallace, Peter George. 2004. The Long European Reformation: Religion, Political Conflict, and the Search for Conformity, 1350–1750. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 95.

- ^ Kamil, Neil (2005). Neil Kamil, Fortress of the soul: violence, metaphysics, and material life, p. 148. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801873904. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Wandel, Lee Palmer (1995). Voracious Idols and Violent Hands. Cambridge, UK: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 149. ISBN 978-0-521-47222-7.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (22 October 2009). The Reformation. Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0191578885.

Iconoclastic incidents during the Calvinist 'Second Reformation' in Germany provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs, while Protestant image-breaking in the Baltic region deeply antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox, a group with whom reformers might have hoped to make common cause.

- ^ Kleiner, Fred S. (2010). Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Concise History of Western Art. Cengage Learning. p. 254. ISBN 978-1424069224.

In an episode known as the Great Iconoclasm, bands of Calvinists visited Catholic churches in the Netherlands in 1566, shattering stained-glass windows, smashing statues, and destroying paintings and other artworks they perceived as idolatrous.

- ^ Stark, Rodney (2007). The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success. Random House Publishing Group. p. 176. ISBN 978-1588365002.

The Beeldenstorm, or Iconoclastic Fury, involved roving bands of radical Calvinists who were utterly opposed to all religious images and decorations in churches and who acted on their beliefs by storming into Catholic churches and destroying all artwork and finery.

- ^ Byfield, Ted (2002). A Century of Giants, A.D. 1500 to 1600: In an Age of Spiritual Genius, Western Christendom Shatters. Christian History Project. p. 297. ISBN 978-0968987391.

Devoutly Catholic but opposed to Inquisition tactics, they backed William of Orange in subduing the Calvinist uprising of the Dutch beeldenstorm on behalf of regent Margaret of Parma, and had come willingly to the council at her invitation.

- ^ Aston, Margaret (1993), The King's Bedpost: Reformation and Iconography in a Tudor Group Portrait, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48457-2.

- ^ Loach, Jennifer (1999), Bernard, George; Williams, Penry (eds.), Edward VI, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 187, ISBN 978-0-300-07992-0

- ^ Hearn, Karen (1995), Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England 1530–1630, New York: Rizzoli, pp. 75–76, ISBN 978-0-8478-1940-9

- ^ Heal, Felicity (2005), Reformation in Britain and Ireland, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-928015-5 (pp. 263–264)

- ^ Evelyn White, Parliamentary Visitor (1886). "The Journal of William Dowsing, Parliamentary Visitor" (PDF). Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. VI (Part 2): 236 to 295.

- ^ Naaeke, Anthony Y. (2006). Kaleidoscope Catechesis: Missionary Catechesis in Africa, Particularly in the Diocese of Wa in Ghana. Peter Lang. p. 114. ISBN 978-0820486857.

Although some reformers, such as John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli, rejected all images, Martin Luther defended the importance of images as tools for instruction and aids to devotion.

- ^ Noble, Bonnie (2009). Lucas Cranach the Elder: Art and Devotion of the German Reformation. University Press of America. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-0761843375.

- ^ a b Spicer, Andrew (2016). Lutheran Churches in Early Modern Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 237. ISBN 978-1351921169.

As it developed in north-eastern Germany, Lutheran worship became a complex ritual choreography set in a richly furnished church interior. This much is evident from the background of an epitaph pained in 1615 by Martin Schulz, destined for the Nikolaikirche in Berlin (see Figure 5.5.).

- ^ Dixon, C. Scott (2012). Contesting the Reformation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 146. ISBN 978-1118272305.

According to Koerner, who dwells on Lutheran art, the Reformation renewed rather than removed the religious image.

- ^ Ohl, Jeremiah F. 1906. "Art in Worship". pp. 83–99 in Memoirs of the Lutheran Liturgical Association 2. Pittsburgh: Lutheran Liturgical Association.

- ^ İnalcık, Halil (1974). "The Turkish Impact on the Development of Modern Europe". In Karpat, K. H. (ed.). The Ottoman State and Its Place in World History: Introduction. Armenian Research Center collection. Leiden: Brill. p. 53. ISBN 978-90-04-03945-2.

- ^ Miller, Roland E. (2006). Muslims and the Gospel: Bridging the Gap : a Reflection on Christian Sharing. Kirk House Publishers. ISBN 978-1932688078 – via Google Books.

- ^ Art after iconoclasm: painting in the Netherlands between 1566 and 1585. Turnhout: Brepols. 2012. ISBN 978-2-503-54596-7.

- ^ Strathern, Alan (2020). "The Many Meanings of Iconoclasm: Warrior and Christian Temple-Shrine Destruction in Late Sixteenth Century Japan". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (3): 163–193. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10023. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 229468278.

- ^ Fischer, Steven Roger (2006). Island at the end of the world: The turbulent history of Easter Island. London: Reaktion. p. 64. ISBN 1-86189-282-9. OCLC 646808462.

- ^ Wellington, Victoria University of (April 4, 2014). "New view of Polynesian conversion to Christianity". Victoria University of Wellington.

- ^ Chessman, Stuart. "Hetzendorf and the Iconoclasm in the Second Half of the 20th Century". The Society of St. Hugh of Cluny. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ a b c d Flood, Finbarr Barry (2002). "Between cult and culture: Bamiyan, Islamic iconoclasm, and the museum". The Art Bulletin. 84 (4): 641–659. doi:10.2307/3177288. JSTOR 3177288.

- ^ Guillaume, Alfred (1955). The Life of Muhammad. A translation of Ishaq's "Sirat Rasul Allah". Oxford University Press. p. 552. ISBN 978-0-19-636033-1. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

Quraysh had put pictures in the Ka'ba including two of Jesus son of Mary and Mary (on both of whom be peace!). ... The apostle ordered that the pictures should be erased except those of Jesus and Mary.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Grabar, André (1984) [1957]. L'iconoclasme byzantin: le dossier archéologique [Byzantine iconoclasm: The archaeological record]. Champs (in French). Flammarion. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-2-08-012603-0.

- ^ King, G. R. D. (1985). "Islam, iconoclasm, and the declaration of doctrine". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 48 (2): 276–277. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00033346. S2CID 162882785.

- ^ "What happened to the Sphinx's nose?". Smithsonian Journeys. Smithsonian Institution. December 8, 2009.

- ^ Zivie-Coche, Christiane (2004). Sphinx : history of a monument. Ithaca : Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801489549 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Howden, Daniel (August 6, 2005). "Independent Newspaper on-line, London, Jan 19, 2007". News.independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 8, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ Ahmed, Irfan (2006). "The Destruction of Holy Sites in Mecca and Medina". Islamica Magazine. No. 15. Archived from the original on 5 February 2006. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Afghan Taliban leader orders destruction of ancient statues". Rawa.org. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (2012-07-02). "Timbuktu's Destruction: Why Islamists Are Wrecking Mali's Cultural Heritage". Time. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Nine Years for the Cultural Destruction of Timbuktu". The Atlantic. 2016-09-27. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "Iraq jihadists blow up 'Jonah's tomb' in Mosul". The Telegraph. Agence France-Presse. 25 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "ISIS destroys Prophet Sheth shrine in Mosul". Al Arabiya News. 26 July 2014. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (9 December 2000). "Temple desecration in pre-modern India". Frontline. Vol. 17, no. 25. The Hindu Group. "In 642 A.D." (pp. 65–66). Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Eaton, Richard M. (1 September 2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3). Oxford University Press: 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283. ISSN 0955-2340.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (2004). Temple desecration and Muslim states in medieval India. Gurgaon: Hope India Publications. ISBN 978-8178710273.

- ^ Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg: The Chachnamah, An Ancient History of Sind, Giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. [1] Archived 2017-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sindhi Culture by U. T. Thakkur, Univ. of Bombay Publications, 1959. [ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (5 January 2001). "Temple desecration and Indo-Muslim states" (PDF). Frontline. Vol. 17, no. 26. The Hindu Group. p. 73 – via Columbia University, item 16 of the Table. Issue 26 online.

- ^ Gopal, Ram (1994). Hindu culture during and after Muslim rule: survival and subsequent challenges. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 148. ISBN 81-85880-26-3.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (1996). The Hindu nationalist movement and Indian politics: 1925 to the 1990s. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 1-85065-170-1.

- ^ Bradnock, Robert; Bradnock, Roma (2000). India Handbook. McGraw-Hill. p. 959. ISBN 978-0-658-01151-1.

- ^ "Gujarat State Portal | All About Gujarat | Gujarat Tourism | Religious Places | Somnath Temple". Gujaratindia.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-28. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2005). Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History. Verso. ISBN 978-1844670208 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Yagnik, Achyut, and Suchitra Sheth. 2005. Shaping of Modern Gujarat. Penguin UK. ISBN 8184751850.

- ^ a b Thapar, Romila. 2004. Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History. Penguin Books India. ISBN 1-84467-020-1.

- ^ Akbar, M. J. 2003. The Shade of Swords: Jihad and the Conflict between Islam and Christianity. Roli Books. ISBN 978-9351940944.

- ^ Somnath Temple Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, British Library.

- ^ "Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Welch, Anthony, and Howard Crane. 1983. "The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate". Muqarnas 1:123–166. JSTOR 1523075: The Quwwatu'l-Islam was built with the remains of demolished Hindu and Jain temples.

- ^ Pritchett, Frances W. "Indian routes: Some memorable ventures, adventures, and other happenings, in and about south Asia: 1200–1299" – via Columbia University.

- ^ Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, 3rd Edition, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0-415-15482-0, pp. 160–161

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2002). The Puffin History of India for Children, 3000 BC – AD 1947. Penguin Books. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-14-333544-3.

- ^ Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor. E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume 4. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-097902. p. 793

- ^ Firishta, Muhammad Qāsim Hindū Shāh (1981) [1829]. Tārīkh-i-Firishta [History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India]. Translated by John Briggs. New Delhi.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Elliot and Dowson. "The Muhammadan Period". pp. 457–459 in The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians, Vol. 6. London: Trubner & Co. p. 457.

- ^ Donaldson, Thomas (2003). Konark. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-0-19-567591-7. OCLC 52861120.

- ^ Behera, Mahendra Narayan (2003). Brownstudy on heathenland: A book on Indology. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-7618-2652-1. OCLC 53385077.

- ^ Pauwels, Heidi; Bachrach, Emilia (2018). "Aurangzeb as Iconoclast? Vaishnava Accounts of the Krishna images' Exodus from Braj". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 28 (3): 485–508. doi:10.1017/S1356186318000019. ISSN 1356-1863. S2CID 165273975.

- ^ Andrew Spicer (2016). Parish Churches in the Early Modern World. Taylor & Francis. pp. 309–311. ISBN 978-1-351-91276-1.

- ^ Teotonio R. De Souza (2016). The Portuguese in Goa, in Acompanhando a Lusofonia em Goa: Preocupações e experiências pessoais (PDF). Lisbon: Grupo Lusofona. pp. 28–30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Herbert, Sir Thomas (1677). Some years travels into divers parts of Africa, and Asia the Great. London : R. Everingham for R. Scot, etc. p. 40.

- ^ Narula, Smita (October 1999). India politics by other means: Attacks Against Christians in India (Report). Vol. 11. Human Rights Watch. § The Context of Anti-Christian Violence.

- ^ Tully, Mark (5 December 2002). "Tearing down the Babri Masjid". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Lary, Diana (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925–1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-521-20204-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Don Alvin Pittman (2001). Toward a modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu's reforms. University of Hawaii Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8248-2231-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b Lary, Diana (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925–1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-521-20204-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Karan, P. P. (2015). "Suppression of Tibetan Religious Heritage". The Changing World Religion Map. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 461–476. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9376-6_23. ISBN 978-9401793759.

- ^ Wells, Harry L. 2000. "Korean Temple Burnings and Vandalism: The Response of the Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies". Buddhist-Christian Studies 20:239–240. doi:10.1353/bcs.2000.0035.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p. 133.

- ^ Hedrick, Charles W. (2000). History and Silence: Purge and Rehabilitation of Memory in Late Antiquity. University of Texas Press. pp. 88–130.

- ^ Stewart, Peter (2003). Statues in Roman Society: Representation and Response. Oxford University Press. pp. 279–283.

- ^ Beiner, Guy (2007). Remembering the Year of the French: Irish Folk History and Social Memory. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 305.

- ^ Beiner, Guy (2018). Forgetful Remembrance: Social Forgetting and Vernacular Historiography of a Rebellion in Ulster. Oxford University Press. pp. 369–384.

- ^ Beiner, Guy (2021). "When Monuments Fall: The Significance of Decommemorating". Éire-Ireland. 56 (1): 33–61. doi:10.1353/eir.2021.0001. S2CID 240526743.

- ^ Idzerda, Stanley J. (1954). "Iconoclasm during the French Revolution". The American Historical Review. 60/1 (1): 13–26. doi:10.2307/1842743. JSTOR 1842743.

- ^ a b Lindsay, Suzanne Glover (18 October 2014). "The Revolutionary Exhumations at St-Denis, 1793". Center for the Study of Material & Visual Cultures of Religion. Yale University.

- ^ Thompson, Victoria E. (Fall–Winter 2012). "The Creation, Destruction and Recreation of Henri IV: Seeing Popular Sovereignty in the Statue of a King". History and Memory. 24 (2): 5–40. doi:10.2979/histmemo.24.2.5. JSTOR 10.2979/histmemo.24.2.5. S2CID 159942339.

- ^ Oliver, Bette Wyn (2007). From Royal to National: The Louvre Museum and the Bibliothèque Nationale. Lexington Books. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-7391-1861-0. OCLC 70883061.

- ^ Foucault, Michel (1986). "Of Other Spaces". Diacritics. 16 (1). Translated by Miskowiec, Jay. Johns Hopkins University Press: 22–27. doi:10.2307/464648. ISSN 0300-7162. JSTOR 464648. Translated from "Des Espace Autres". Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité (in French) (5): 46–49. October 1984. Alternate translation available in Leach, Neil, ed. (1997). "Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias" (PDF). Rethinking Architecture: A Reader in Cultural Theory. Routledge. pp. 330–336. ISBN 978-0-415-12826-1.

- ^ Stanley J. Idzerda, "Iconoclasm during the French Revolution". In The American Historical Review, Vol. 60, No. 1 (Oct., 1954), p. 25.

- ^ Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987): 212–213.

- ^ Greene, Christopher M., "Alexandre Lenoir and the Musée des monuments français during the French Revolution", French Historical Studies 12, no. 2 (1981): pp. 200–222.

- ^ Ellul, Michael (1982). "Art and Architecture in Malta in the Early Nineteenth Century" (PDF). Melitensia Historica. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2016.

- ^ Westcott, Kathryn (18 January 2013). "Letter boxes: The red heart of the British streetscape". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016.

- ^ Bonello, Giovanni (14 January 2018). "Mysteries of the Main Guard inscription". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018.

- ^ Mardaga 1993, p. 121.

- ^ Hennaut 2000, p. 34–36.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (1980). "The Martyrdom of Ferrer". The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-0-691-04669-3. OCLC 489692159, p. 33.

- ^ Goldstone, Nancy Bazelon; Goldstone, Lawrence (2003). Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World. New York: Broadway. pp. 313–316. ISBN 978-0-7679-0837-5.

- ^ Uriona, Alberto (6 March 2000). "El Ayuntamiento de Bilbao restituye a su columna el busto de Unamuno nueve meses después de su robo". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Camacho, Isabel (9 June 1999). "La cabeza perdida de don Miguel". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "Victorio Macho y Unamuno: notas para un centenario" (PDF) (in Spanish). Real Fundación Toledo. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Göttke, Florian. Toppled. Rotterdam: Post Editions, 2010.

- ^ Meintjies, Ilze-Marie (16 February 2016). "Protesting UCT Students Burn Historic Paintings, Refuse To Leave". Eyewitness News.

- ^ "Zlatan Ibrahimovic statue: Vandals try to saw through feet". BBC Sport. 12 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019 – via BBC News.

- ^ Daniels, Tim. "Zlatan Ibrahimovic's Malmo Statue Set on Fire After Becoming Hammarby Part Owner". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Erberth, Nellie (December 22, 2019). "Zlatans staty vandaliserad igen – näsan avsågad". SVT Nyheter – via www.svt.se.

- ^ Wikén, Johan; Erberth, Nellie (January 5, 2020). "Zlatanstatyn vandaliserad igen – avsågad vid fötterna". SVT Nyheter – via www.svt.se.

- ^ a b "Protesters in England topple statue of slave trader Edward Colston into harbor". CBS News. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b Siddique, Haroon (7 June 2020). "BLM protesters topple statue of Bristol slave trader Edward Colston". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Zaks, Dmitry (8 June 2020). "UK slave trader's statue toppled in anti-racism protests". The Jakarta Post. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "George Floyd death: Protesters tear down slave trader statue". BBC News. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Rory (7 June 2020). "Black Lives Matter protesters pull down statue of 17th century UK slave trader". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Christopher Wharton, "The Hammer and Sickle: The Role of Symbolism and Rituals in the Russian Revolution" Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Auyezov, Olzhas (January 5, 2011). "Ukraine says blowing up Stalin statue was terrorism". Reuters. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ The Destruction of the Royal Statue at New York on July 9, 1776

- ^ A Toppled Statue of George III Illuminates the Ongoing Debate Over America’s Monuments

- ^ Pulling down statues? It’s a tradition that dates back to U.S. independence

- ^ "SEE IT: Crowd pulls down Confederate statue in North Carolina". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ Holland, Jesse J. "Deadly rally accelerates ongoing removal of Confederate statues across U.S." chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ "War over Confederate statues reveals simple thinking on all sides". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ Jackson, Amanda (15 August 2017). "Protesters pull down Confederate statue in North Carolina". CNN. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ Fultz, Matthew (7 June 2020). "Crew heard cheers as Confederate general's statue toppled in Monroe Park". WTVR.

- ^ Taylor, Alan. "Photos: The Statues Brought Down Since the George Floyd Protests Began". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ Ebrahimji, Alisha; Moshtaghian, Artemis. "These confederate statues have been removed since George Floyd's death". CNN. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- ^ "San Francisco Archbishop Outraged Over Toppling Of Golden Gate Park Junipero Serra Statue". 2020-06-21. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ Schneider, Gregory S.; Vozzella, Laura (2021-09-08). "Robert E. Lee statue is removed in Richmond, ex-capital of Confederacy, after months of protests and legal resistance". Washington Post. Retrieved 2021-09-08.

- ^ a b Asmelash, Leah (10 June 2020). "Statues of Christopher Columbus are being dismounted across the country". CNN. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- ^ a b Williams, David (19 June 2020). "Protesters tore down a George Washington statue and set a fire on its head". CNN. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

Further reading

[edit]- Alloa, Emmanuel (2013). "Visual Studies in Byzantium: A Pictorial Turnavant la lettre". Journal of Visual Culture. 12 (1). Sage: 3–29. doi:10.1177/1470412912468704. ISSN 1470-4129. S2CID 191395643. (On the conceptual background of Byzantine iconoclasm)

- Aston, Margaret (1988). England's Iconoclasts: Laws against images. Vol. 1. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822438-9.

- —— 2016. Broken Idols of the English Reformation. Cambridge University Press.

- Balafrej, Lamia (2 September 2015). "Islamic iconoclasm, visual communication and the persistence of the image". Interiors. 6 (3). Informa UK: 351–366. doi:10.1080/20419112.2015.1125659. ISSN 2041-9112. S2CID 131284640.

- Barasch, Moshe. 1992. Icon: Studies in the History of an Idea. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1172-9.

- Beiner, Guy (2021). "When Monuments Fall: The Significance of Decommemorating". Éire-Ireland. 56 (1): 33–61. doi:10.1353/eir.2021.0001. S2CID 240526743.

- Besançon, Alain. 2000. The Forbidden Image: An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-04414-9.

- Bevan, Robert. 2006. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-319-2.

- Boldrick, Stacy, Leslie Brubaker, and Richard Clay, eds. 2014. Striking Images, Iconoclasms Past and Present. Ashgate. (Scholarly studies of the destruction of images from prehistory to the Taliban.)

- Calisi, Antonio. 2017. I Difensori Dell'icona: La Partecipazione Dei Vescovi Dell'Italia Meridionale Al Concilio Di Nicea II 787. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1978401099.

- Freedberg, David. 1977. "The Structure of Byzantine and European Iconoclasm". Pp. 165–77 in Iconoclasm: Papers Given at the Ninth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, edited by A. Bryer and J. Herrin. University of Birmingham, Centre for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 978-0-7044-0226-3.

- —— [1985] 1993. "Iconoclasts and their Motives", (Second Horst Gerson Memorial Lecture, University of Groningen). Public 8(Fall).

- Original print: Maarssen: Gary Schwartz. 1985. ISBN 978-90-6179-056-3.

- Gamboni, Dario (1997). The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-316-1.

- Gwynn, David M (2007). "From Iconoclasm to Arianism: The Construction of Christian Tradition in the Iconoclast Controversy" (PDF). Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 47: 225–251. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-16. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- Hennaut, Eric (2000). La Grand-Place de Bruxelles. Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). Vol. 3. Brussels: Éditions de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale.

- Ivanovic, Filip (2010). Symbol and Icon: Dionysius the Areopagite and the Iconoclastic Crisis. Pickwick. ISBN 978-1-60899-335-2.

- Karahan, Anne (2014). "Byzantine Iconoclasm: Ideology and Quest for Power". In Kolrud, Kristine; Prusac, M. (eds.). Iconoclasm from antiquity to modernity. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. pp. 75–94. ISBN 978-1-4094-7033-5. OCLC 841051222.

- Lambourne, Nicola (2001). War Damage in Western Europe: The Destruction of Historic Monuments During the Second World War. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1285-7.

- Narain, Harsh (1993). The Ayodhya Temple Mosque Dispute: Focus on Muslim Sources. Delhi: Penman Publishers.

- Shourie, Arun, Sita Ram Goel, Harsh Narain, Jay Dubashi, and Ram Swarup. 1990. Hindu Temples – What Happened to Them Vol. I, (A Preliminary Survey). ISBN 81-85990-49-2

- Spicer, Andrew (2017). "Iconoclasm". Renaissance Quarterly. 70 (3). Cambridge University Press: 1007–1022. doi:10.1086/693887. ISSN 0034-4338. S2CID 233344068.

- Topper, David R. Idolatry & Infinity: Of Art, Math & God. BrownWalker. ISBN 978-1-62734-506-4.

- Velikov, Yuliyan (2011). Obrazŭt na Nevidimii︠a︡ : ikonopochitanieto i ikonootrit︠s︡anieto prez osmi vek [Image of the Invisible. Image Veneration and Iconoclasm in the Eighth Century] (in Bulgarian). Veliko Tarnovo: Veliko Tarnovo University. ISBN 978-954-524-779-8. OCLC 823743049.

- Weeraratna, Senaka ' Repression of Buddhism in Sri Lanka by the Portuguese' (1505–1658) Archived 2021-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Teodoro Studita, Contro gli avversari delle icone, Emanuela Fogliadini (Prefazione), Antonio Calisi (Traduttore), Jaca Book, 2022, ISBN 978-8816417557

- Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique: Bruxelles (PDF) (in French). Vol. 1B: Pentagone E-M. Liège: Pierre Mardaga. 1993.

External links

[edit]- Iconoclasm in England, Holy Cross College (UK)

- Design as Social Agent at the ICA by Kerry Skemp, April 5, 2009

![16th-century iconoclasm in the Protestant Reformation. Relief statues in St. Stevenskerk in Nijmegen, Netherlands, were attacked and defaced by Calvinists in the Beeldenstorm.[36][37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/2008-09_Nijmegen_st_stevens_beeldenstorm.JPG/500px-2008-09_Nijmegen_st_stevens_beeldenstorm.JPG)

![The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 AD.[73] The present temple was reconstructed in Chalukyan style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[74][75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg/500px-Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg)

![Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[69]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Warangal_fort.jpg/250px-Warangal_fort.jpg)

![Rani Ki Vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[69]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Rani_ki_vav1.jpg/500px-Rani_ki_vav1.jpg)

![Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0e/Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg/960px-Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg)