Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Andrei Rublev

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Andrei Rublev (Russian: Андрей Рублёв, romanized: Andrey Rublyov,[1] IPA: [ɐnˈdrʲej rʊˈblʲɵf] ⓘ; c. 1360 – c. 1430)[2][3] was a Russian artist considered to be one of the greatest medieval Russian painters of Orthodox Christian icons and frescoes. He is revered as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, and his feast day is 29 January.[4]

Early life

[edit]Little information survives about his life; even where he was born is unknown. He probably lived in the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, near Moscow, under Nikon of Radonezh, who became hegumen after the death of Sergius of Radonezh in 1392. The first mention of Rublev is in 1405, when he decorated icons and frescos for the Cathedral of the Annunciation of the Moscow Kremlin, in company with Theophanes the Greek and Prokhor of Gorodets. His name was the last of the list of masters, as the junior both by rank and by age. Theophanes was an important Byzantine master, who moved to Russia and is considered to have trained Rublev.

Career

[edit]Chronicles tell us that together with Daniel Chorny he painted the Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir in 1408 as well as the Trinity Cathedral in the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius between 1425 and 1427. After Daniel's death, Andrei came to Moscow's Andronikov Monastery where he painted his last work, the frescoes of the Saviour Cathedral. He is also believed to have painted at least one of the miniatures in the Khitrovo Gospels.

The only work authenticated as entirely his is the icon of the Trinity (c. 1410), removed in 2023 from the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow to the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.[5] It is based on an earlier icon known as the "Hospitality of Abraham" (illustrating Genesis 18). Rublev removed the figures of Abraham and Sarah from the scene, and through a subtle use of composition and symbolism changed the subject to focus on the Mystery of the Trinity.

In Rublev's art two traditions are combined: the highest asceticism and the classic harmony of Byzantine mannerism. The characters of his paintings are always peaceful and calm. After some time his art came to be perceived as the ideal of Eastern Church painting and of Orthodox iconography.

Death and legacy

[edit]Rublev died at Andronikov Monastery between 1427 and 1430. Rublev's work influenced many artists including Dionisy. The Stoglavi Sobor (1551) promulgated Rublev's icon style as a model for church painting. Since 1959, the Andrei Rublev Museum at the Andronikov Monastery has displayed his and related art.

The Russian Orthodox Church canonized Rublev as a saint in 1988, celebrating his feast day on 29 January[6] and/or on 4 July.[6][7][8]

In 1966, Andrei Tarkovsky made a film Andrei Rublev, loosely based on the artist's life. This became the first (and perhaps only) film produced in the Soviet era to treat the artist as a world-historic figure and Christianity as an axiom of Russia's historical identity,[9] during a turbulent period in the history of Russia.

Historian Serge Aleksandrovich Zenkovsky wrote that the names of Andrei Rublev, Epiphanius the Wise, Sergius of Radonezh and Stephen of Perm "signify the Russian spiritual and cultural revival of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries".[10] He also wrote: "The wonderful icons and frescoes of Andrey Rublev offered a harmonious and colorful expression of the spirit of complete serenity and humility. For the Russian people these icons became the finest achievement of religious art and the highest expression of Russian spirituality".[10]

Veneration

[edit]- 29 January – commemoration of his death anniversary (Greek Orthodox Church)[11][12]

- 12/13 June – feast day, Synaxis of All of Andronikov Monastery (with Andronicus, Sabbas, Alexander, Abbots of Moscow and Daniel the Black, the icon painter)[13]

- 4 July – main feast day from the list of "Russian saints of Moscow and Vladimir" by Nikodim (Kononov),

- 6 July – Synaxis of All Saints of Radonezh

- Synaxis of all saints of Moscow – movable holiday on the Sunday before 26 August (ROC)[14]

Selected works

[edit]-

Baptism of Jesus, 1405 (Cathedral of the Annunciation, Moscow)

-

Annunciation, 1405 (Cathedral of the Annunciation, Moscow)

-

Version of the Theotokos of Vladimir, c. 1405

-

St. Gabriel, 1408 (Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir)

-

St. Andrew the First-called, 1408 (Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir)

-

St. Gregory the Theologian, 1408 (Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir)

-

Theotokos from Deësis, 1408 (Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir) Some think this may be the work of Theophanes the Greek

-

St. John the Theologian, 1408 (Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir)

-

St. John the Baptist, 1408 (Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir)

-

The Saviour Enthroned in Glory, Christ in Majesty, 1408 (Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir)

-

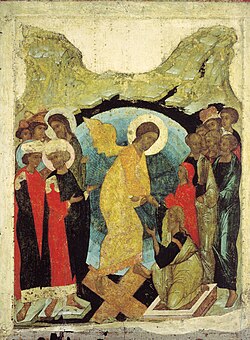

Harrowing of Hell, 1408–1410 (Vladimir)

-

Ascension, 1408 (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

-

Apostle Paul, 1410s (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

References

[edit]- ^ The Getty Union Artist Name List prefers "Rublyov", but "Rublev" is more commonly found.

- ^ The concise encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Chichester: Wiley. 2014. p. 403. ISBN 9781118759332.

- ^ "Venerable Andrew Rublev the Iconographer". www.oca.org.

- ^ "Orthodox Calendar. HOLY TRINITY RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH, a parish of the Patriarchate of Moscow". HOLY TRINITY RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH, a parish of the Patriarchate of Moscow. Retrieved 2024-05-09.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Holy Trinity painting on display in Moscow". BBC News. 2023-06-05. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

- ^ a b Saint Herman Calendar 2006. Platina CA: Saint Herman of Alaska Brotherhood. 2006. pp. 12, 56.

- ^ "Главная". fond.ru. Archived from the original on July 21, 2006.

- ^ "Moscow Patriarchate Glorifies Saints", Orthodox America, vol. IX, no. 82, August 1988, archived from the original on 2008-07-05, retrieved 2008-03-16

- ^ Hoberman, Jim. "Andrei Rublev". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ a b Zenkovsky, Serge A. (1963). Medieval Russia's Epics, Chronicles, and Tales. Dutton. p. 205.

- ^ "January 29, 2015. + Orthodox Calendar". orthochristian.com. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ^ "Ορθόδοξος Συναξαριστής :: Άγιος Ανδρέας Ρουμπλιόβ ο Εικονογράφος". www.saint.gr. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ^ "АНДРЕЙ РУБЛЁВ". www.pravenc.ru. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ^ "АНДРЕЙ РУБЛЕВ - Древо". drevo-info.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-07-16.

Sources

[edit]- Andrei Rublev, a 1966 film by Andrei Tarkovsky loosely based on the painter's life.

- Mikhail V. Alpatov, Andrey Rublev, Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1972.

- Gabriel Bunge, The Rublev Trinity, transl. Andrew Louth, St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, Crestwood, New York, 2007.

- Sergius Golubtsov, Voplosh’enie bogoslovskih idey v tvorchestve prepodobnogo Andreya Rubleva [The realization of theological ideas in creative works of Andrey Rublev]. Bogoslovskie trudy 22, 20–40, 1981.

- Troitca Andreya Rubleva [The Trinity of Andrey Rublev], Gerold I. Vzdornov (ed.), Moscow: Iskusstvo 1989.

- Viktor N. Lazarev, The Russian Icon: From Its Origins to the Sixteenth Century, Gerold I. Vzdornov (ed.). Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1997.

- Priscilla Hunt, Andrei Rublev's Old Testament Trinity Icon in Cultural Context, The Trinity-Sergius Lavr in Russian History and Culture: Readings in Russian Religious Culture, vol. 3, ed. Deacon Vladimir Tsurikov, (Jordanville, NY: Holy Trinity Seminary Press, 2006), 99-122.(See on-line at phslavic.com)

- Priscilla Hunt, Andrei Rublev's Old Testament Trinity Icon: Problems of Meaning, Intertextuality, and Transmission, Symposion: A Journal of Russian (Religious) Thought, ed. Roy Robson, 7-12 (2002–2007), 15-46 (See on-line at www.phslavic.com)

- Konrad Onasch, Das Problem des Lichtes in der Ikonomalerei Andrej Rublevs. Zur 600–Jahrfeier des grossen russischen Malers, vol. 28. Berlin: Berliner byzantinische Arbeiten, 1962.

- Konrad Onasch, Das Gedankenmodell des byzantisch–slawischen Kirchenbaus. In Tausend Jahre Christentum in Russland, Karl Christian Felmy et al. (eds.), 539–543. Go¨ ttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1988.

- Eugeny N. Trubetskoi, Russkaya ikonopis'. Umozrenie w kraskah. Wopros o smysle vizni w drewnerusskoj religioznoj viwopisi [Russian icon painting. Colourful contemplation. Question of the meaning of life in early Russian religious painting], Moscow: Beliy Gorod, 2003 [1916].

- Georgij Yu. Somov, Semiotic systemity of visual artworks: Case study of The Holy Trinity by Rublev, Semiotica 166 (1/4), 1-79, 2007.

External links

[edit]- Andrey Rublev Official Web Site

- Rublev at the Russian Art Gallery

- Selected works by Andrei Rublev: icons, frescoes and miniatures

- "The Deesis painted by Andrey Rublev" from the Annunciation Church of the Moscow Kremlin - article by Dr. Oleg G. Uliyanov

- Historical documentation on Andrei Rublev, compiled by Robert Bird

- Venerable Andrew Rublev the Iconographer Orthodox icon and synaxarion

Andrei Rublev

View on GrokipediaBiography

Origins and Early Training

Andrei Rublev, whose birth date is uncertain but estimated around the 1360s, likely originated from the Moscow region or nearby areas in central Russia, during a period of monastic revival and rising influence of the Eastern Orthodox Church.[7] [8] His surname may derive from a family trade involving tanning hides, though no direct records confirm his precise birthplace or early family circumstances, reflecting the scarcity of contemporary documentation on medieval Russian artists. Rublev entered monastic life as a lay brother at the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra near Moscow, founded by St. Sergius of Radonezh, where he resided under the guidance of Abbot Nikon of Radonezh following Sergius's death in 1392.[9] [10] This monastery served as a key center for spiritual and artistic development, aligning with the hesychast traditions emphasizing inner prayer and theological contemplation that would influence his later work. His early training in iconography occurred within this monastic environment, likely through apprenticeship in Moscow-area workshops, where he absorbed Byzantine techniques introduced by immigrant artists.[8] Primary instruction is attributed to Theophanes the Greek, a Byzantine master active in Moscow from the 1370s to 1405, known for his learned and philosophical approach to painting; Rublev collaborated with him on documented projects, suggesting prior tutelage.[2] He may also have worked alongside the monk Daniel, a lifelong associate, honing skills in fresco and icon production amid the era's church-building efforts under Muscovite patronage.[8] The first historical record of Rublev appears in 1405, noting his participation in frescoes for Moscow's Annunciation Cathedral alongside Theophanes and Prokhor of Gorodets, indicating his training had advanced to professional levels by early adulthood.[11]Monastic Life and Key Associations

Andrei Rublev entered monastic life at the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra near Moscow, where he spent much of his career as a monk dedicated to iconography and fresco painting as acts of spiritual service.[9] The monastery, founded by St. Sergius of Radonezh around 1337, served as Rublev's primary spiritual home, with Sergius's emphasis on hesychastic prayer and communal asceticism profoundly influencing his monastic discipline and artistic expression.[12] Following Sergius's death in 1392, Rublev lived under the guidance of hegumen Nikon of Radonezh, continuing the founder's legacy of monastic rigor amid the challenges of 15th-century Muscovite Russia, including Tatar incursions and internal church reforms.[9] Rublev's key associations included Theophanes the Greek, a Byzantine émigré painter who arrived in Moscow around 1370 and with whom Rublev collaborated on major commissions, likely serving initially as an assistant before emerging as a peer.[13] Their partnership bridged Byzantine traditions with emerging Russian styles, evident in joint work on frescoes for the Moscow Kremlin's Annunciation Cathedral in 1405.[14] Another significant collaborator was Prokhor of Gorodets, with whom Rublev painted icons and frescoes for the same cathedral, highlighting a workshop dynamic that combined Greek mastery, local expertise, and monastic piety.[14] These associations not only advanced Rublev's technical skills but also embedded his work within the Orthodox Church's liturgical and theological framework, prioritizing divine contemplation over secular innovation.Major Artistic Commissions

Rublev's first documented commission occurred in 1405, when he collaborated with Theophanes the Greek and Prokhor of Gorodets to paint the frescoes and icons for the newly constructed Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Moscow Kremlin.[3][2] This project marked the earliest historical reference to Rublev, involving the creation of monumental religious scenes such as the Nativity, Baptism, and Annunciation, executed in tempera on walls and panels to adorn the grand princely church.[15] The works emphasized harmonious compositions and luminous colors, reflecting a synthesis of Byzantine traditions with emerging Russian stylistic innovations under the patronage of Grand Prince Vasily I.[2] In 1408, Rublev received a commission alongside the monk Daniil Chernyi to execute the frescoes for the Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir, restoring and enhancing the 12th-century interior with new cycles depicting the Last Judgment and other eschatological themes.[8][16] This effort, ordered by the church hierarchy, covered extensive wall surfaces with figures of apostles, saints, and angelic hierarchies, preserving fragments that demonstrate Rublev's skill in integrating narrative depth with spiritual serenity amid the cathedral's stone architecture.[17] The project underscored his growing reputation for monastic and ecclesiastical decoration, though much of the original paint has deteriorated due to later restorations and environmental factors.[16] Rublev's most renowned commission involved the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, where he painted the icon of the Holy Trinity around 1411–1427, likely at the request of Abbot Nikon to honor St. Sergius of Radonezh, the monastery's founder.[18] This tempera-on-wood panel, depicting three angels in a Eucharistic interpretation of the Old Testament hospitality of Abraham, was installed in the Trinity Cathedral and exemplifies Rublev's mature style of contemplative harmony and subtle symbolism.[19] Chronicles also record his participation in frescoes for the same cathedral during 1425–1427, further solidifying his role in adorning key monastic sites central to Russian Orthodox spirituality.[3] These works, executed under direct ecclesiastical oversight, prioritized theological expression over ornamental excess, influencing subsequent iconographic traditions.[20]Artistic Works

Firmly Attributed Icons

The only icon definitively attributed solely to Andrei Rublev is the Old Testament Trinity, painted circa 1410 and preserved in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.[21] This attribution stems from an inscription discovered on the reverse in the early 20th century, linking it directly to Rublev, unlike other works associated with his workshop or collaborators.[12] The icon illustrates the three angels who appeared to Abraham and Sarah in Genesis 18, interpreted in Orthodox theology as a prefiguration of the Holy Trinity.[20] Measuring approximately 142 by 114 centimeters, the panel employs tempera on wood, featuring a circular composition centered on a table laden with symbolic elements: a chalice foreshadowing the Eucharist, a sacrificial lamb, and cups representing divine hospitality.[2] Rublev's style emphasizes harmony and inward spirituality, with elongated figures in soft, luminous colors—blues, golds, and whites—conveying serenity and unity, departing from more rigid Byzantine precedents toward a gentler, more humanistic expression.[4] Originally destined for the Trinity Cathedral at Sergiev Posad (then the Trinity-Sergius Lavra), it exemplifies Rublev's mature synthesis of hesychast mysticism and visual grace.[15] Art historians regard this work as the pinnacle of Russian iconography, influencing subsequent Orthodox art through its balance of theological depth and aesthetic refinement.[20] Conservation efforts, including restorations in 1918 and later, have preserved its integrity, confirming the attribution through stylistic consistency with documented aspects of Rublev's oeuvre.[19] No other surviving icons bear comparable direct evidence of his sole authorship, rendering the Trinity uniquely emblematic of his artistic achievement.[21]Disputed or Collaboratively Attributed Works

Rublev participated in collaborative projects with Theophanes the Greek, including the decoration of the Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Moscow Kremlin in 1405, where surviving icons such as the Nativity of Jesus, Baptism of Jesus, and Annunciation are attributed to the workshop but lack definitive individual authorship due to the joint effort involving multiple artists.[22] Similarly, in 1408, Rublev worked with Prokhor of Gorodets on icons for the Trinity Cathedral at the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, though only the *Holy Trinity* icon is securely linked to Rublev alone, with other festal icons from the same commission showing stylistic variations suggestive of assistants or co-workers.[23] ![Christ the Redeemer, c. 1410 ][float-right] The Zvenigorod Deesis tier, comprising icons of Christ the Redeemer, Apostle Paul, and Archangel Michael (c. 1410–1420s), has traditionally been attributed to Rublev based on stylistic similarities to his confirmed works and historical association with Zvenigorod cathedrals, but recent scientific analysis, including pigment examination and comparative restoration studies, indicates inconsistencies in technique and materials that suggest authorship by a contemporary workshop artist rather than Rublev himself.[24][25] Scholars note that these icons' ground layers and underdrawings differ from those in Rublev's Trinity, supporting reattribution to an unidentified master active around the same period.[26] In the Deesis row of the Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir (1408), icons such as St. John the Baptist, St. John the Theologian, and the Theotokos are often linked to Rublev's circle, but the Theotokos panel shows traits closer to Theophanes the Greek's Byzantine-influenced manner, leading some experts to credit it primarily to him while viewing others as Rublev's contributions or joint efforts.[27] These attributions rely on historical chronicles mentioning Rublev's involvement in the project, yet overpainting and restorations complicate precise delineation, with art historians emphasizing workshop practices over singular authorship.[28] Overall, such collaborative and disputed works highlight the challenges of attribution in 15th-century Russian iconography, where guild-like teams produced ensembles under master oversight, and few pieces bear direct signatures or unambiguous documentary evidence.[6]Painting Techniques and Materials

Rublev's icons were executed using the egg tempera technique standard to 14th- and 15th-century Russian iconography, involving the mixture of dry, natural mineral and organic pigments—such as azurite for blues, vermilion for reds, and ochres for earth tones—with an emulsion binder of egg yolk diluted in water or vinegar, which allowed for quick-drying layers that built translucency and depth through successive glazes.[29][30] This medium adhered directly to the absorbent gesso ground, enabling the fine brushwork and subtle tonal gradations characteristic of his style, as seen in the soft modeling of figures without heavy impasto.[31] The support for these paintings consisted of wooden panels, often crafted from limewood, pine, or alder, meticulously prepared with a multi-layered gesso primer made from gypsum or chalk bound with animal glue (typically rabbit skin glue), applied in coarse and fine boluses to create a polished, white surface that enhanced pigment vibrancy and prevented wood warping through repeated sizing with glue solutions.[32][30] Areas intended for gold, such as backgrounds and halos, received a red bole underlayer—a clay-glue mixture—over which 22- or 24-karat gold leaf was laid and burnished to a reflective finish, symbolizing uncreated light and integrated via sgraffito incisions or punched ornamentation for decorative borders.[33][34] In addition to solid gold leaf, Rublev incorporated shell gold—finely powdered gold suspended in a gum arabic medium—for hatching and assist work, creating delicate linear highlights on garments and architectural elements that added dimensionality without opacity, as evidenced in the intricate detailing of icons like those from the Dormition Cathedral iconostasis.[33] Techniques such as scumbling, where thin, translucent paint layers were lightly rubbed over underpaint to diffuse edges and evoke spiritual harmony, distinguished his approach, particularly in achieving the luminous, unified color fields in blue-greens and warm accents of the *Holy Trinity* icon, painted around 1410.[31] Post-painting, surfaces were sometimes protected with thin olifa varnishes derived from linseed oil, though many of Rublev's surviving works show original unpainted states due to later cleanings.[35]Theological and Iconographic Contributions

Symbolism and Hesychast Influences

Rublev's iconography embodies Hesychast principles, a 14th-century Eastern Orthodox tradition emphasizing inner stillness (hesychia), repetitive prayer, and the vision of God's uncreated light as pathways to theosis or deification. This theology, systematized by Gregory Palamas against rationalist critics, posits a distinction between God's unknowable essence and His knowable energies, allowing direct experiential communion without pantheistic fusion. Rublev, working in the monastic milieu of St. Sergius of Radonezh—who propagated Hesychasm in Muscovy—integrated these ideas into visual form, prioritizing contemplative invitation over didactic narrative.[36][37][38] In the Old Testament Trinity icon, commissioned around 1411 for the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, Rublev symbolizes the divine perichoresis—the mutual indwelling of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—through a circular arrangement of three angels seated at a table, evoking Genesis 18's hospitality to Abraham while transcending literalism. The central figure, interpreted as the Son, inclines toward a chalice symbolizing the Eucharistic offering and Passion, with the right angel (Father) gesturing approval and the left (Spirit) in receptive posture, fostering a dynamic of eternal counsel and self-giving love. This configuration invites the viewer into the divine banquet, mirroring Hesychast ascent from created symbols to uncreated realities.[39][40][41] Symbolic elements further align with Hesychast ontology: ethereal blue hues on the angels' garments denote transcendent unity and the uncreated light's manifestation, distinct from earthly tones; the hill, tree, and edifice in the background represent the Church's cosmic scope, from Golgotha to eschatological fulfillment. Absent are Abraham's servants or overt Old Testament details, emphasizing apophatic mystery over kataphatic description, as Hesychast prayer purges discursive thought for direct illumination. Rublev's sparing use of line and subtle asymmetry conveys motion within repose, reflecting Palamite energies as both immanent and dynamic.[41][39][42] This Hesychast-infused symbolism extends to other works, such as the Vladimir Deesis icons (c. 1408), where figures' gazes and inclinations suggest contemplative reciprocity, embodying the Trinity's relational essence as a model for human deification. Scholarly analyses attribute Rublev's departure from rigid Byzantine schemata to this theological depth, enabling icons as "windows to heaven" that facilitate noetic prayer rather than mere veneration.[43][44][2]Departures from Byzantine Predecessors

Andrei Rublev's iconographic approach represented a notable evolution from the hierarchical and austere conventions of Byzantine art, incorporating greater emphasis on harmonious unity and contemplative serenity. This shift aligned with hesychast theology, which stressed the perception of uncreated divine light through inner prayer, manifesting in Rublev's serene figures and luminous effects that softened the rigid abstraction of predecessors. His style retained Orthodox spiritual priorities but introduced more accessible emotional depth, diverging from the formalized intellectualism of Byzantine icons.[4][23] Stylistically, Rublev employed flowing silhouettes, minimal contours, and subtle modeling to achieve pictorial depth and graceful movement in figures, contrasting the flat, sharply delineated forms characteristic of Byzantine tradition. He favored brighter, translucent colors—such as golden yellows, azure blues, and cinnabar reds—over muted, symbolic palettes, creating an aura of optimism and inner light that evoked divine presence rather than stark asceticism. These choices reflected Russian monastic influences, including Novgorodian elements like concise compositions and lively expressions, while departing from Byzantine discipline.[4][2] In composition, Rublev pioneered circular arrangements symbolizing theological interdependence, as exemplified in his Old Testament Trinity (c. 1411), where the three angels form a balanced, Eucharistic-focused mandorla, omitting extraneous narrative figures like Abraham and Sarah present in earlier versions to prioritize divine communion. This contrasted Byzantine linear hierarchies and didactic narratives, fostering instead a sense of perichoretic harmony suited to hesychast contemplation. Similarly, his introduction of full-length saints in iconostases, rather than the half-figures standard in Byzantine screens, enhanced spatial dynamism and viewer engagement.[4][23][2] Rublev's figures often displayed gentle, compassionate expressions and averted gazes, promoting private devotion over confrontational symbolism, and imbued holy personages with humanistic warmth without compromising transcendence. These departures, rooted in the spiritual ethos of figures like Sergius of Radonezh, elevated Russian iconography toward a distinct synthesis of Byzantine inheritance and local innovation, influencing subsequent Moscow School developments.[4][2]