Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Impasto

View on Wikipedia

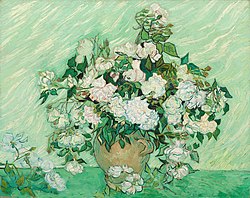

Impasto is a technique used in painting where paint is laid on an area of the surface thickly,[1] usually thick enough that the brush or painting-knife strokes are visible. Paint can also be mixed right on the canvas. When dry, impasto provides texture; the paint appears to be coming out of the canvas.

Etymology

[edit]The word impasto is Italian in origin; in which it means "dough" or "mixture"; related to the verb impastare, "to knead", or "to paste". Italian usage of impasto includes both a painting and a potting technique. The root noun of impasto is pasta, meaning "paste".[2]

Media

[edit]Oil paint is the traditional medium for impasto painting, due to its thick consistency and slow drying time. Acrylic paint can also be used for impasto by adding heavy body acrylic gels. Impasto is generally not used in watercolor or tempera without the addition of thickening agent due to the inherent thinness of these media. An artist working in pastels can produce a limited impasto effect by pressing a soft pastel firmly against the paper.

Purposes

[edit]The impasto technique serves several purposes. First, it makes the light reflect in a particular way, giving the artist additional control over the play of light in the painting. Second, it can add expressiveness to the painting, with the viewer being able to notice the strength and speed by which the artist applied the paint. Third, impasto can push a piece from a painting to a three-dimensional sculptural rendering. The first objective was originally sought by masters such as Rembrandt, Titian, and Vermeer, to represent folds in clothes or jewels: it was then juxtaposed with a more delicate painting style. Much later, the French Impressionists created pieces covering entire canvases with rich impasto textures. Vincent van Gogh used it frequently for aesthetics and expression. Abstract expressionists such as Hans Hofmann and Willem de Kooning also made extensive use of it, motivated in part by a desire to create paintings which dramatically record the action of painting itself. Still more recently, Frank Auerbach has used such heavy impasto that some of his paintings become nearly three-dimensional.

Impasto gives texture to a painting, meaning that it may be contrasted with more flat, smooth, or blended painting styles.

Artists

[edit]Many artists have used the impasto technique. Some of the more notable ones including: Rembrandt van Rijn, Diego Velázquez, Vincent van Gogh, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning.

- Selected examples of paintings which make use of the impasto technique

-

Crags and Crevices by Jane Frank (1960). As with many abstract expressionist works (and many so-called "action paintings" as well), impasto is a prominent feature.

-

Taos Mountain, Trail Home by Cordelia Wilson (1920). A landscape entirely executed with a bold impasto technique.

-

Starry Night by van Gogh (1889). The impasto technique and line structure gives his viewers the feeling that the sky is moving.[3]

-

Self Portrait by Rembrandt (1660). His use of impasto was surely inspired by Titian, and the addition of impasto showed a new method of illusion in the artist's work.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Impasto. In: Weyer, Angela; Roig Picazo, Pilar; Pop, Daniel; Cassar, JoAnn; Özköse, Aysun; Jean-Marc, Vallet; Srša, Ivan (Ed.) (2015). Weyer, Angela; Roig Picazo, Pilar; Pop, Daniel; Cassar, JoAnn; Özköse, Aysun; Vallet, Jean-Marc; Srša, Ivan (eds.). EwaGlos. European Illustrated Glossary Of Conservation Terms For Wall Paintings And Architectural Surfaces. English Definitions with translations into Bulgarian, Croatian, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Romanian, Spanish and Turkish. Petersberg: Michael Imhof. p. 100. doi:10.5165/hawk-hhg/233. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ^ Webster's New World dictionary of the American language. Guralnik, David B. (David Bernard), 1920-2000. (New rev., expanded pocket-size ed.). New York, N.Y.: Warner Books. 1982. ISBN 0446311928. OCLC 10638582.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Naifeh, Steven, 1952- (2011). Van Gogh : the life. Smith, Gregory White. (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 9781588360472. OCLC 763401387.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Walter Liedtke, Carolyn Logan, Nadine M. Orenstein, Stephanie S. Dickey, “Rubens and Rembrandt: A Comparison of Their Techniques,” Rembrandt/not Rembrandt in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.

External links

[edit] Media related to Impasto (painting) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Impasto (painting) at Wikimedia Commons- Lindberg, Ted. Alfred Currier: Impasto

- National Portrait Gallery, London. Impasto

- Tate Britain Gallery, London. Frank Auerbach, Bacchus & Ariadne.

- How to thin acrylic paint Easy Achieve Beautiful.

- Acrylic Impasto Acrylic Impasto Techniques by Anastasia Trusova

![Starry Night by van Gogh (1889). The impasto technique and line structure gives his viewers the feeling that the sky is moving.[3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e8/Van_Gogh_-_Starry_Night_-_Google_Art_Project-x0-y0.jpg/330px-Van_Gogh_-_Starry_Night_-_Google_Art_Project-x0-y0.jpg)

![Self Portrait by Rembrandt (1660). His use of impasto was surely inspired by Titian, and the addition of impasto showed a new method of illusion in the artist's work.[4]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2d/Rembrandt_-_Self-portrait%2C_1660.JPG/330px-Rembrandt_-_Self-portrait%2C_1660.JPG)