Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Antiparticle.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Antiparticle

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Antiparticle

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

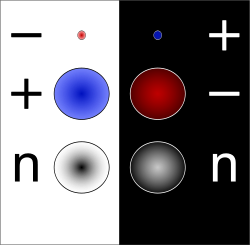

In particle physics, an antiparticle is a subatomic particle that has the same mass, spin, and lifetime as its corresponding particle in the Standard Model but opposite values for additive quantum numbers, including electric charge, baryon number, lepton number, and certain flavor quantum numbers like strangeness.[1] For instance, the antiparticle of the negatively charged electron is the positively charged positron, while the antiproton carries a negative charge opposite to the proton's positive charge.[2] These particles arise naturally within quantum field theory, where fields are quantized and inherently produce both particle and antiparticle states to satisfy mathematical consistency, such as the requirement for charge conjugation symmetry.[1]

The concept of antiparticles was theoretically predicted in 1930 by Paul Dirac in his paper "A Theory of Electrons and Protons," where he interpreted negative-energy solutions in his relativistic quantum equation for the electron as "holes" representing positively charged particles of the same mass—the first indication of antimatter.[3] This prediction resolved inconsistencies in combining special relativity and quantum mechanics for electrons, suggesting that every fermion has an antiparticle partner.[4] Experimental confirmation came swiftly: in 1932, Carl David Anderson discovered the positron while studying cosmic rays using a cloud chamber, observing tracks of particles with the mass of an electron but curving in the direction expected for positive charge in a magnetic field.[5]

Antiparticles play a crucial role in fundamental interactions and are routinely produced and studied in high-energy environments. When a particle and its antiparticle collide, they annihilate, converting their combined mass into energy, typically in the form of photons or other particles, as governed by conservation laws in the Standard Model.[1] Production occurs in particle accelerators like those at Fermilab or CERN, where collisions generate antiparticle-antiparticle pairs, or naturally via cosmic rays and radioactive decays such as beta-plus emission.[2] Notable milestones include the 1955 discovery of the antiproton at the Berkeley Bevatron by Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain, confirming Dirac's prediction for hadrons and earning them the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Beyond fundamental research, antiparticles have practical applications, particularly in medicine through positron emission tomography (PET) scans, where positrons from radioactive tracers annihilate with electrons to produce detectable gamma rays for imaging.[2] Antimatter research also probes cosmological questions, such as the observed matter-antimatter asymmetry in the universe, where theories like CP violation in weak interactions explain why matter dominates despite symmetric Big Bang production.[6] Ongoing experiments at facilities like CERN's Antiproton Decelerator continue to explore antimatter's properties, including antihydrogen spectroscopy, to test whether it behaves identically to matter under gravity and electromagnetism.