Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Matter

View on Wikipedia

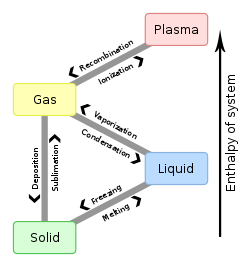

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume.[1] All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic particles. In everyday as well as scientific usage, matter generally includes atoms and anything made up of them, and any particles (or combination of particles) that act as if they have both rest mass and volume. However it does not include massless particles such as photons, or other energy phenomena or waves such as light or heat.[1]: 21 [2] Matter exists in various states (also known as phases). These include classical everyday phases such as solid, liquid, and gas – for example water exists as ice, liquid water, and gaseous steam – but other states are possible, including plasma, Bose–Einstein condensates, fermionic condensates, and quark–gluon plasma.[3]

Usually atoms can be imagined as a nucleus of protons and neutrons, and a surrounding "cloud" of orbiting electrons which "take up space".[4][5] However, this is only somewhat correct because subatomic particles and their properties are governed by their quantum nature, which means they do not act as everyday objects appear to act – they can act like waves as well as particles, and they do not have well-defined sizes or positions. In the Standard Model of particle physics, matter is not a fundamental concept because the elementary constituents of atoms are quantum entities which do not have an inherent "size" or "volume" in any everyday sense of the word. Due to the exclusion principle and other fundamental interactions, some "point particles" known as fermions (quarks, leptons), and many composites and atoms, are effectively forced to keep a distance from other particles under everyday conditions; this creates the property of matter which appears to us as matter taking up space.

For much of the history of the natural sciences, people have contemplated the exact nature of matter. The idea that matter was built of discrete building blocks, the so-called particulate theory of matter, appeared in both ancient Greece and ancient India.[6] Early philosophers who proposed the particulate theory of matter include the Indian philosopher Kaṇāda (c. 6th century BCE),[7] and the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers Leucippus (c. 490 BCE) and Democritus (c. 470–380 BCE).[8]

Related concepts

[edit]Comparison with mass

[edit]Matter is a general term describing any physical substance, which is sometimes defined in incompatible ways in different fields of science. Some definitions are based on historical usage from a time when there was no reason to distinguish mass from simply a quantity of matter. By contrast, mass is not a substance but a well-defined, extensive property of matter and other substances or systems. Various types of mass are defined within physics – including rest mass, inertial mass, and relativistic mass.

In physics, matter is sometimes equated with particles that exhibit rest mass (i.e., that cannot travel at the speed of light), such as quarks and leptons. However, in both physics and chemistry, matter exhibits both wave-like and particle-like properties (the so-called wave–particle duality).[9][10][11]

Relation with chemical substance

[edit]

A chemical substance is a unique form of matter with constant chemical composition and characteristic properties.[12][13] Chemical substances may take the form of a single element or chemical compounds. If two or more chemical substances can be combined without reacting, they may form a chemical mixture.[14] If a mixture is separated to isolate one chemical substance to a desired degree, the resulting substance is said to be chemically pure.[15]

Chemical substances can exist in several different physical states or phases (e.g. solids, liquids, gases, or plasma) without changing their chemical composition. Substances transition between these phases of matter in response to changes in temperature or pressure. Some chemical substances can be combined or converted into new substances by means of chemical reactions. Chemicals that do not possess this ability are said to be inert.

Pure water is an example of a chemical substance, with a constant composition of two hydrogen atoms bonded to a single oxygen atom (i.e. H2O). The atomic ratio of hydrogen to oxygen is always 2:1 in every molecule of water. Pure water will tend to boil near 100 °C (212 °F), an example of one of the characteristic properties that define it. Other notable chemical substances include diamond (a form of the element carbon), table salt (NaCl; an ionic compound), and refined sugar (C12H22O11; an organic compound).Definition

[edit]Based on atoms

[edit]A definition of "matter" based on its physical and chemical structure is: matter is made up of atoms.[16] Such atomic matter is also sometimes termed ordinary matter. As an example, deoxyribonucleic acid molecules (DNA) are matter under this definition because they are made of atoms. This definition can be extended to include charged atoms and molecules, so as to include plasmas (gases of ions) and electrolytes (ionic solutions), which are not obviously included in the atoms definition. Alternatively, one can adopt the protons, neutrons, and electrons definition.

Based on protons, neutrons and electrons

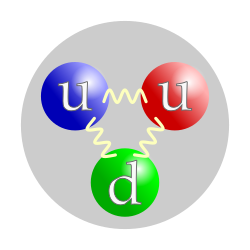

[edit]A definition of "matter" more fine-scale than the atoms and molecules definition is: matter is made up of what atoms and molecules are made of, meaning anything made of positively charged protons, neutral neutrons, and negatively charged electrons.[17] This definition goes beyond atoms and molecules, however, to include substances made from these building blocks that are not simply atoms or molecules, for example, electron beams in an old cathode ray tube television, or white dwarf matter—typically, carbon and oxygen nuclei in a sea of degenerate electrons. At a microscopic level, the constituent "particles" of matter such as protons, neutrons, and electrons obey the laws of quantum mechanics and exhibit wave-particle duality. At an even deeper level, protons and neutrons are made up of quarks and the force fields (gluons) that bind them together, leading to the next definition.

Based on quarks and leptons

[edit]

As seen in the above discussion, many early definitions of what can be called "ordinary matter" were based on its structure or "building blocks". On the scale of elementary particles, a definition that follows this tradition can be stated as: "ordinary matter is everything that is composed of quarks and leptons", or "ordinary matter is everything that is composed of any elementary fermions except antiquarks and antileptons".[18][19][20] The connection between these formulations follows.

Leptons (the most famous being the electron), and quarks (of which baryons, such as protons and neutrons, are made) combine to form atoms, which in turn form molecules. Because atoms and molecules are said to be matter, it is natural to phrase the definition as: "ordinary matter is anything that is made of the same things that atoms and molecules are made of". (However, notice that one also can make from these building blocks matter that is not atoms or molecules.) Then, because electrons are leptons, and protons and neutrons are made of quarks, this definition in turn leads to the definition of matter as being "quarks and leptons", which are two of the four types of elementary fermions (the other two being antiquarks and antileptons, which can be considered antimatter as described later). Carithers and Grannis state: "Ordinary matter is composed entirely of first-generation particles, namely the [up] and [down] quarks, plus the electron and its neutrino."[19] (Higher generations particles quickly decay into first-generation particles, and thus are not commonly encountered.[21])

This definition of ordinary matter is more subtle than it first appears. All the particles that make up ordinary matter (leptons and quarks) are elementary fermions, while all the force carriers are elementary bosons.[22] The W and Z bosons that mediate the weak force are not made of quarks or leptons, and so are not ordinary matter, even if they have mass.[23] In other words, mass is not something that is exclusive to ordinary matter.

The quark–lepton definition of ordinary matter, however, identifies not only the elementary building blocks of matter, but also includes composites made from the constituents (atoms and molecules, for example). Such composites contain an interaction energy that holds the constituents together, and may constitute the bulk of the mass of the composite. As an example, to a great extent, the mass of an atom is simply the sum of the masses of its constituent protons, neutrons and electrons. However, digging deeper, the protons and neutrons are made up of quarks bound together by gluon fields (see dynamics of quantum chromodynamics) and these gluon fields contribute significantly to the mass of hadrons.[24] In other words, most of what composes the "mass" of ordinary matter is due to the binding energy of quarks within protons and neutrons.[25] For example, the sum of the mass of the three quarks in a nucleon is approximately 12.5 MeV/c2, which is low compared to the mass of a nucleon (approximately 938 MeV/c2).[26][27] The bottom line is that most of the mass of everyday objects comes from the interaction energy of its elementary components.

The Standard Model groups matter particles into three generations, where each generation consists of two quarks and two leptons. The first generation is the up and down quarks, the electron and the electron neutrino; the second includes the charm and strange quarks, the muon and the muon neutrino; the third generation consists of the top and bottom quarks and the tau and tau neutrino.[28] The most natural explanation for this would be that quarks and leptons of higher generations are excited states of the first generations. If this turns out to be the case, it would imply that quarks and leptons are composite particles, rather than elementary particles.[29]

This quark–lepton definition of matter also leads to what can be described as "conservation of (net) matter" laws—discussed later below. Alternatively, one could return to the mass–volume–space concept of matter, leading to the next definition, in which antimatter becomes included as a subclass of matter.

Based on elementary fermions (mass, volume, and space)

[edit]A common or traditional definition of matter is "anything that has mass and volume (occupies space)".[30][31] For example, a car would be said to be made of matter, as it has mass and volume (occupies space).

The observation that matter occupies space goes back to antiquity. However, an explanation for why matter occupies space is recent, and is argued to be a result of the phenomenon described in the Pauli exclusion principle,[32][33] which applies to fermions. Two particular examples where the exclusion principle clearly relates matter to the occupation of space are white dwarf stars and neutron stars, discussed further below.

Thus, matter can be defined as everything composed of elementary fermions. Although we do not encounter them in everyday life, antiquarks (such as the antiproton) and antileptons (such as the positron) are the antiparticles of the quark and the lepton, are elementary fermions as well, and have essentially the same properties as quarks and leptons, including the applicability of the Pauli exclusion principle which can be said to prevent two particles from being in the same place at the same time (in the same state), i.e. makes each particle "take up space". This particular definition leads to matter being defined to include anything made of these antimatter particles as well as the ordinary quark and lepton, and thus also anything made of mesons, which are unstable particles made up of a quark and an antiquark.

In general relativity and cosmology

[edit]In the context of relativity, mass is not an additive quantity, in the sense that one cannot add the rest masses of particles in a system to get the total rest mass of the system.[1]: 21 In relativity, usually a more general view is that it is not the sum of rest masses, but the energy–momentum tensor that quantifies the amount of matter. This tensor gives the rest mass for the entire system. Matter, therefore, is sometimes considered as anything that contributes to the energy–momentum of a system, that is, anything that is not purely gravity.[34][35] This view is commonly held in fields that deal with general relativity such as cosmology. In this view, light and other massless particles and fields are all part of matter.

Structure

[edit]In particle physics, fermions are particles that obey Fermi–Dirac statistics. Fermions can be elementary, like the electron—or composite, like the proton and neutron. In the Standard Model, there are two types of elementary fermions: quarks and leptons, which are discussed next.

Quarks

[edit]Quarks are massive particles of spin-1⁄2, implying that they are fermions. They carry an electric charge of −1⁄3 e (down-type quarks) or +2⁄3 e (up-type quarks). For comparison, an electron has a charge of −1 e. They also carry colour charge, which is the equivalent of the electric charge for the strong interaction. Quarks also undergo radioactive decay, meaning that they are subject to the weak interaction.

| name | symbol | spin | electric charge (e) |

mass (MeV/c2) |

mass comparable to | antiparticle | antiparticle symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| up-type quarks | |||||||

| up | u | 1⁄2 | +2⁄3 | 1.5 to 3.3 | ~ 5 electrons | antiup | u |

| charm | c | 1⁄2 | +2⁄3 | 1160 to 1340 | ~ 1 proton | anticharm | c |

| top | t | 1⁄2 | +2⁄3 | 169,100 to 173,300 | ~ 180 protons or ~1 tungsten atom |

antitop | t |

| down-type quarks | |||||||

| down | d | 1⁄2 | −1⁄3 | 3.5 to 6.0 | ~10 electrons | antidown | d |

| strange | s | 1⁄2 | −1⁄3 | 70 to 130 | ~ 200 electrons | antistrange | s |

| bottom | b | 1⁄2 | −1⁄3 | 4130 to 4370 | ~ 5 protons | antibottom | b |

Baryonic

[edit]

Baryons are strongly interacting fermions, and so are subject to Fermi–Dirac statistics. Amongst the baryons are the protons and neutrons, which occur in atomic nuclei, but many other unstable baryons exist as well. The term baryon usually refers to triquarks—particles made of three quarks. Also, "exotic" baryons made of four quarks and one antiquark are known as pentaquarks, but their existence is not generally accepted.

Baryonic matter is the part of the universe that is made of baryons (including all atoms). This part of the universe does not include dark energy, dark matter, black holes or various forms of degenerate matter, such as those that compose white dwarf stars and neutron stars. Microwave light seen by Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) suggests that only about 4.6% of that part of the universe within range of the best telescopes (that is, matter that may be visible because light could reach us from it) is made of baryonic matter. About 26.8% is dark matter, and about 68.3% is dark energy.[37]

The great majority of ordinary matter in the universe is unseen, since visible stars and gas inside galaxies and clusters account for less than 10 per cent of the ordinary matter contribution to the mass–energy density of the universe.[38]

Hadronic

[edit]Hadronic matter can refer to 'ordinary' baryonic matter, made from hadrons (baryons and mesons), or quark matter (a generalisation of atomic nuclei), i.e. the 'low' temperature QCD matter.[39] It includes degenerate matter and the result of high energy heavy nuclei collisions.[40]

Degenerate

[edit]In physics, degenerate matter refers to the ground state of a gas of fermions at a temperature near absolute zero.[41] The Pauli exclusion principle requires that only two fermions can occupy a quantum state, one spin-up and the other spin-down. Hence, at zero temperature, the fermions fill up sufficient levels to accommodate all the available fermions—and in the case of many fermions, the maximum kinetic energy (called the Fermi energy) and the pressure of the gas becomes very large, and depends on the number of fermions rather than the temperature, unlike normal states of matter.

Degenerate matter is thought to occur during the evolution of heavy stars.[42] The demonstration by Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar that white dwarf stars have a maximum allowed mass because of the exclusion principle caused a revolution in the theory of star evolution.[43]

Degenerate matter includes the part of the universe that is made up of neutron stars and white dwarfs.

Strange

[edit]Strange matter is a particular form of quark matter, usually thought of as a liquid of up, down, and strange quarks. It is contrasted with nuclear matter, which is a liquid of neutrons and protons (which themselves are built out of up and down quarks), and with non-strange quark matter, which is a quark liquid that contains only up and down quarks. At high enough density, strange matter is expected to be color superconducting. Strange matter is hypothesized to occur in the core of neutron stars, or, more speculatively, as isolated droplets that may vary in size from femtometers (strangelets) to kilometers (quark stars).

Two meanings

[edit]In particle physics and astrophysics, the term is used in two ways, one broader and the other more specific.

- The broader meaning is just quark matter that contains three flavors of quarks: up, down, and strange. In this definition, there is a critical pressure and an associated critical density, and when nuclear matter (made of protons and neutrons) is compressed beyond this density, the protons and neutrons dissociate into quarks, yielding quark matter (probably strange matter).

- The narrower meaning is quark matter that is more stable than nuclear matter. The idea that this could happen is the "strange matter hypothesis" of Bodmer[44] and Witten.[45] In this definition, the critical pressure is zero: the true ground state of matter is always quark matter. The nuclei that we see in the matter around us, which are droplets of nuclear matter, are actually metastable, and given enough time (or the right external stimulus) would decay into droplets of strange matter, i.e. strangelets.

Leptons

[edit]Leptons are particles of spin-1⁄2, meaning that they are fermions. They carry an electric charge of −1 e (charged leptons) or 0 e (neutrinos). Unlike quarks, leptons do not carry colour charge, meaning that they do not experience the strong interaction. Leptons also undergo radioactive decay, meaning that they are subject to the weak interaction. Leptons are massive particles, therefore are subject to gravity.

| name | symbol | spin | electric charge (e) |

mass (MeV/c2) |

mass comparable to | antiparticle | antiparticle symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| charged leptons[46] | |||||||

| electron | e− |

1⁄2 | −1 | 0.5110 | 1 electron | antielectron | e+ |

| muon | μ− |

1⁄2 | −1 | 105.7 | ~ 200 electrons | antimuon | μ+ |

| tau | τ− |

1⁄2 | −1 | 1,777 | ~ 2 protons | antitau | τ+ |

| neutrinos[47] | |||||||

| electron neutrino | ν e |

1⁄2 | 0 | < 0.000460 | < 1⁄1000 electron | electron antineutrino | ν e |

| muon neutrino | ν μ |

1⁄2 | 0 | < 0.19 | < 1⁄2 electron | muon antineutrino | ν μ |

| tau neutrino | ν τ |

1⁄2 | 0 | < 18.2 | < 40 electrons | tau antineutrino | ν τ |

Phases

[edit]

In bulk, matter can exist in several different forms, or states of aggregation, known as phases,[48] depending on ambient pressure, temperature and volume.[49] A phase is a form of matter that has a relatively uniform chemical composition and physical properties (such as density, specific heat, refractive index, and so forth). These phases include the three familiar ones (solids, liquids, and gases), as well as more exotic states of matter (such as plasmas, superfluids, supersolids, Bose–Einstein condensates, ...). A fluid may be a liquid, gas or plasma. There are also paramagnetic and ferromagnetic phases of magnetic materials. As conditions change, matter may change from one phase into another. These phenomena are called phase transitions and are studied in the field of thermodynamics. In nanomaterials, the vastly increased ratio of surface area to volume results in matter that can exhibit properties entirely different from those of bulk material, and not well described by any bulk phase (see nanomaterials for more details).

Phases are sometimes called states of matter, but this term can lead to confusion with thermodynamic states. For example, two gases maintained at different pressures are in different thermodynamic states (different pressures), but in the same phase (both are gases).

Antimatter

[edit]Antimatter is matter that is composed of the antiparticles of those that constitute ordinary matter. If a particle and its antiparticle come into contact with each other, the two annihilate; that is, they may both be converted into other particles with equal energy in accordance with Albert Einstein's equation E = mc2. These new particles may be high-energy photons (gamma rays) or other particle–antiparticle pairs. The resulting particles are endowed with an amount of kinetic energy equal to the difference between the rest mass of the products of the annihilation and the rest mass of the original particle–antiparticle pair, which is often quite large. Depending on which definition of "matter" is adopted, antimatter can be said to be a particular subclass of matter, or the opposite of matter.

Antimatter is not found naturally on Earth, except very briefly and in vanishingly small quantities (as the result of radioactive decay, lightning or cosmic rays). This is because antimatter that came to exist on Earth outside the confines of a suitable physics laboratory would almost instantly meet the ordinary matter that Earth is made of, and be annihilated. Antiparticles and some stable antimatter (such as antihydrogen) can be made in tiny amounts, but not in enough quantity to do more than test a few of its theoretical properties.

There is considerable speculation both in science and science fiction as to why the observable universe is apparently almost entirely matter (in the sense of quarks and leptons but not antiquarks or antileptons), and whether other places are almost entirely antimatter (antiquarks and antileptons) instead. In the early universe, it is thought that matter and antimatter were equally represented, and the disappearance of antimatter requires an asymmetry in physical laws called CP (charge–parity) symmetry violation, which can be obtained from the Standard Model,[50] but at this time the apparent asymmetry of matter and antimatter in the visible universe is one of the great unsolved problems in physics. Possible processes by which it came about are explored in more detail under baryogenesis.

Formally, antimatter particles can be defined by their negative baryon number or lepton number, while "normal" (non-antimatter) matter particles have positive baryon or lepton number.[51] These two classes of particles are the antiparticle partners of one another.

In October 2017, scientists reported further evidence that matter and antimatter, equally produced at the Big Bang, are identical, should completely annihilate each other and, as a result, the universe should not exist.[52] This implies that there must be something, as yet unknown to scientists, that either stopped the complete mutual destruction of matter and antimatter in the early forming universe, or that gave rise to an imbalance between the two forms.

Conservation

[edit]Two quantities that can define an amount of matter in the quark–lepton sense (and antimatter in an antiquark–antilepton sense), baryon number and lepton number, are conserved in the Standard Model. A baryon such as the proton or neutron has a baryon number of one, and a quark, because there are three in a baryon, is given a baryon number of 1/3. So the net amount of matter, as measured by the number of quarks (minus the number of antiquarks, which each have a baryon number of −1/3), which is proportional to baryon number, and number of leptons (minus antileptons), which is called the lepton number, is practically impossible to change in any process. Even in a nuclear bomb, none of the baryons (protons and neutrons of which the atomic nuclei are composed) are destroyed—there are as many baryons after as before the reaction, so none of these matter particles are actually destroyed and none are even converted to non-matter particles (like photons of light or radiation). Instead, nuclear (and perhaps chromodynamic) binding energy is released, as these baryons become bound into mid-size nuclei having less energy (and, equivalently, less mass) per nucleon compared to the original small (hydrogen) and large (plutonium etc.) nuclei. Even in electron–positron annihilation, there is no net matter being destroyed, because there was zero net matter (zero total lepton number and baryon number) to begin with before the annihilation—one lepton minus one antilepton equals zero net lepton number—and this net amount matter does not change as it simply remains zero after the annihilation.[53]

In short, matter, as defined in physics, refers to baryons and leptons. The amount of matter is defined in terms of baryon and lepton number. Baryons and leptons can be created, but their creation is accompanied by antibaryons or antileptons; and they can be destroyed by annihilating them with antibaryons or antileptons. Since antibaryons/antileptons have negative baryon/lepton numbers, the overall baryon/lepton numbers are not changed, so matter is conserved. However, baryons/leptons and antibaryons/antileptons all have positive mass, so the total amount of mass is not conserved. Further, outside of natural or artificial nuclear reactions, there is almost no antimatter generally available in the universe (see baryon asymmetry and leptogenesis), so particle annihilation is rare in normal circumstances.

Dark

[edit]- Dark energy (73.0%)

- Dark matter (23.0%)

- Non-luminous matter (3.60%)

- Luminous matter (0.40%)

Ordinary matter, in the quarks and leptons definition, constitutes about 4% of the energy of the observable universe. The remaining energy is theorized to be due to exotic forms, of which 23% is dark matter[55][56] and 73% is dark energy.[57][58]

In astrophysics and cosmology, dark matter is matter of unknown composition that does not emit or reflect enough electromagnetic radiation to be observed directly, but whose presence can be inferred from gravitational effects on visible matter.[62][63] Observational evidence of the early universe and the Big Bang theory require that this matter have energy and mass, but not be composed of ordinary baryons (protons and neutrons). The commonly accepted view is that most of the dark matter is non-baryonic in nature.[62] As such, it is composed of particles as yet unobserved in the laboratory. Perhaps they are supersymmetric particles,[64] which are not Standard Model particles but relics formed at very high energies in the early phase of the universe and still floating about.[62]

Energy

[edit]In cosmology, dark energy is the name given to the source of the repelling influence that is accelerating the rate of expansion of the universe. Its precise nature is currently a mystery, although its effects can reasonably be modeled by assigning matter-like properties such as energy density and pressure to the vacuum itself.[65][66]

Fully 70% of the matter density in the universe appears to be in the form of dark energy. Twenty-six percent is dark matter. Only 4% is ordinary matter. So less than 1 part in 20 is made out of matter we have observed experimentally or described in the standard model of particle physics. Of the other 96%, apart from the properties just mentioned, we know absolutely nothing.

— Lee Smolin (2007), The Trouble with Physics, p. 16

Exotic

[edit]Exotic matter is a concept of particle physics, which may include dark matter and dark energy but goes further to include any hypothetical material that violates one or more of the properties of known forms of matter. Some such materials might possess hypothetical properties like negative mass.

Historical and philosophical study

[edit]The modern conception of matter has been refined many times in history, in light of the improvement in knowledge of just what the basic building blocks are, and in how they interact. The term "matter" is used throughout physics in a wide variety of contexts: for example, one refers to "condensed matter physics",[67] "elementary matter",[68] "partonic" matter, "dark" matter, "anti"-matter, "strange" matter, and "nuclear" matter. In discussions of matter and antimatter, the former has been referred to by Alfvén as koinomatter (Gk. common matter).[69] In physics, there is no broad consensus as to a general definition of matter, and the term "matter" usually is used in conjunction with a specifying modifier.

The history of the concept of matter is a history of the fundamental length scales used to define matter. Different building blocks apply depending upon whether one defines matter on an atomic or elementary particle level. One may use a definition that matter is atoms, or that matter is hadrons, or that matter is leptons and quarks depending upon the scale at which one wishes to define matter.[70]

Classical antiquity

[edit]In ancient India, the Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain philosophical traditions each posited that matter was made of atoms (paramanu, pudgala) that were "eternal, indestructible, without parts, and innumerable" and which associated or dissociated to form more complex matter according to the laws of nature.[6] They coupled their ideas of soul, or lack thereof, into their theory of matter. The strongest developers and defenders of this theory were the Nyaya-Vaisheshika school, with the ideas of the Indian philosopher Kanada being the most followed.[6][7] Buddhist philosophers also developed these ideas in late 1st-millennium CE, ideas that were similar to the Vaisheshika school, but ones that did not include any soul or conscience.[6] Jain philosophers included the soul (jiva), adding qualities such as taste, smell, touch, and color to each atom.[71] They extended the ideas found in early literature of the Hindus and Buddhists by adding that atoms are either humid or dry, and this quality cements matter. They also proposed the possibility that atoms combine because of the attraction of opposites, and the soul attaches to these atoms, transforms with karma residue, and transmigrates with each rebirth.[6]

In ancient Greece, pre-Socratic philosophers speculated the underlying nature of the visible world. Thales (c. 624 BCE–c. 546 BCE) regarded water as the fundamental material of the world. Anaximander (c. 610 BCE–c. 546 BCE) posited that the basic material was wholly characterless or limitless: the Infinite (apeiron). Anaximenes (flourished 585 BCE, d. 528 BCE) posited that the basic stuff was pneuma or air. Heraclitus (c. 535 BCE–c. 475 BCE) seems to say the basic element is fire, though perhaps he means that all is change. Empedocles (c. 490–430 BCE) spoke of four elements of which everything was made: earth, water, air, and fire.[72] Meanwhile, Parmenides argued that change does not exist, and Democritus argued that everything is composed of minuscule, inert bodies of all shapes called atoms, a philosophy called atomism. All of these notions had deep philosophical problems.[73]

Aristotle (384 BCE–322 BCE) was the first to put the conception on a sound philosophical basis, which he did in his natural philosophy, especially in Physics book I.[74] He adopted as reasonable suppositions the four Empedoclean elements, but added a fifth, aether. Nevertheless, these elements are not basic in Aristotle's mind. Rather they, like everything else in the visible world, are composed of the basic principles matter and form.

For my definition of matter is just this—the primary substratum of each thing, from which it comes to be without qualification, and which persists in the result.

— Aristotle, Physics I:9:192a32

The word Aristotle uses for matter, ὕλη (hyle or hule), can be literally translated as wood or timber, that is, "raw material" for building.[75] Indeed, Aristotle's conception of matter is intrinsically linked to something being made or composed. In other words, in contrast to the early modern conception of matter as simply occupying space, matter for Aristotle is definitionally linked to process or change: matter is what underlies a change of substance. For example, a horse eats grass: the horse changes the grass into itself; the grass as such does not persist in the horse, but some aspect of it—its matter—does. The matter is not specifically described (e.g., as atoms), but consists of whatever persists in the change of substance from grass to horse. Matter in this understanding does not exist independently (i.e., as a substance), but exists interdependently (i.e., as a "principle") with form and only insofar as it underlies change. It can be helpful to conceive of the relationship of matter and form as very similar to that between parts and whole. For Aristotle, matter as such can only receive actuality from form; it has no activity or actuality in itself, similar to the way that parts as such only have their existence in a whole (otherwise they would be independent wholes).

Age of Enlightenment

[edit]French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) originated the modern conception of matter. He was primarily a geometer. Unlike Aristotle, who deduced the existence of matter from the physical reality of change, Descartes arbitrarily postulated matter to be an abstract, mathematical substance that occupies space:

So, extension in length, breadth, and depth, constitutes the nature of bodily substance; and thought constitutes the nature of thinking substance. And everything else attributable to body presupposes extension, and is only a mode of an extended thing.

— René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy[76]

For Descartes, matter has only the property of extension, so its only activity aside from locomotion is to exclude other bodies:[77] this is the mechanical philosophy. Descartes makes an absolute distinction between mind, which he defines as unextended, thinking substance, and matter, which he defines as unthinking, extended substance.[78] They are independent things. In contrast, Aristotle defines matter and the formal/forming principle as complementary principles that together compose one independent thing (substance). In short, Aristotle defines matter (roughly speaking) as what things are actually made of (with a potential independent existence), but Descartes elevates matter to an actual independent thing in itself.

The continuity and difference between Descartes's and Aristotle's conceptions is noteworthy. In both conceptions, matter is passive or inert. In the respective conceptions matter has different relationships to intelligence. For Aristotle, matter and intelligence (form) exist together in an interdependent relationship, whereas for Descartes, matter and intelligence (mind) are definitionally opposed, independent substances.[79]

Descartes's justification for restricting the inherent qualities of matter to extension is its permanence, but his real criterion is not permanence (which equally applied to color and resistance), but his desire to use geometry to explain all material properties.[80] Like Descartes, Hobbes, Boyle, and Locke argued that the inherent properties of bodies were limited to extension, and that so-called secondary qualities, like color, were only products of human perception.[81]

English philosopher Isaac Newton (1643–1727) inherited Descartes's mechanical conception of matter. In the third of his "Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy", Newton lists the universal qualities of matter as "extension, hardness, impenetrability, mobility, and inertia".[82] Similarly in Optics he conjectures that God created matter as "solid, massy, hard, impenetrable, movable particles", which were "...even so very hard as never to wear or break in pieces".[83] The "primary" properties of matter were amenable to mathematical description, unlike "secondary" qualities such as color or taste. Like Descartes, Newton rejected the essential nature of secondary qualities.[84]

Newton developed Descartes's notion of matter by restoring to matter intrinsic properties in addition to extension (at least on a limited basis), such as mass. Newton's use of gravitational force, which worked "at a distance", effectively repudiated Descartes's mechanics, in which interactions happened exclusively by contact.[85]

Though Newton's gravity would seem to be a power of bodies, Newton himself did not admit it to be an essential property of matter. Carrying the logic forward more consistently, Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) argued that corporeal properties transcend contact mechanics: chemical properties require the capacity for attraction.[85] He argued matter has other inherent powers besides the so-called primary qualities of Descartes, et al.[86]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]Since Priestley's time, there has been a massive expansion in knowledge of the constituents of the material world (viz., molecules, atoms, subatomic particles). In the 19th century, following the development of the periodic table, and of atomic theory, atoms were seen as being the fundamental constituents of matter; atoms formed molecules and compounds.[87]

The common definition in terms of occupying space and having mass is in contrast with most physical and chemical definitions of matter, which rely instead upon its structure and upon attributes not necessarily related to volume and mass. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the knowledge of matter began a rapid evolution.

Aspects of the Newtonian view still held sway. James Clerk Maxwell discussed matter in his work Matter and Motion.[88] He carefully separates "matter" from space and time, and defines it in terms of the object referred to in Newton's first law of motion.

However, the Newtonian picture was not the whole story. In the 19th century, the term "matter" was actively discussed by a host of scientists and philosophers, and a brief outline can be found in Levere.[89][further explanation needed] One textbook discussion from 1870 suggests that matter is what is made up of atoms:[90]

Three divisions of matter are recognized in science: masses, molecules and atoms.

A Mass of matter is any portion of matter appreciable by the senses.

A Molecule is the smallest particle of matter into which a body can be divided without losing its identity.

An Atom is a still smaller particle produced by division of a molecule.

Rather than simply having the attributes of mass and occupying space, matter was held to have chemical and electrical properties. In 1909 the famous physicist J. J. Thomson (1856–1940) wrote about the "constitution of matter" and was concerned with the possible connection between matter and electrical charge.[91]

In the late 19th century with the discovery of the electron, and in the early 20th century, with the Geiger–Marsden experiment discovery of the atomic nucleus, and the birth of particle physics, matter was seen as made up of electrons, protons and neutrons interacting to form atoms. There then developed an entire literature concerning the "structure of matter", ranging from the "electrical structure" in the early 20th century,[92] to the more recent "quark structure of matter", introduced as early as 1992 by Jacob with the remark: "Understanding the quark structure of matter has been one of the most important advances in contemporary physics."[93][further explanation needed] In this connection, physicists speak of matter fields, and speak of particles as "quantum excitations of a mode of the matter field".[9][10] And here is a quote from de Sabbata and Gasperini: "With the word 'matter' we denote, in this context, the sources of the interactions, that is spinor fields (like quarks and leptons), which are believed to be the fundamental components of matter, or scalar fields, like the Higgs particles, which are used to introduced mass in a gauge theory (and that, however, could be composed of more fundamental fermion fields)."[94][further explanation needed]

Protons and neutrons however are not indivisible: they can be divided into quarks. And electrons are part of a particle family called leptons. Both quarks and leptons are elementary particles, and were in 2004 seen by authors of an undergraduate text as being the fundamental constituents of matter.[95]

These quarks and leptons interact through four fundamental forces: gravity, electromagnetism, weak interactions, and strong interactions. The Standard Model of particle physics is currently the best explanation for all of physics, but despite decades of efforts, gravity cannot yet be accounted for at the quantum level; it is only described by classical physics (see Quantum gravity and Graviton)[96] to the frustration of theoreticians like Stephen Hawking. Interactions between quarks and leptons are the result of an exchange of force-carrying particles such as photons between quarks and leptons.[97] The force-carrying particles are not themselves building blocks. As one consequence, mass and energy (which to our present knowledge cannot be created or destroyed) cannot always be related to matter (which can be created out of non-matter particles such as photons, or even out of pure energy, such as kinetic energy).[citation needed] Force mediators are usually not considered matter: the mediators of the electric force (photons) possess energy (see Planck relation) and the mediators of the weak force (W and Z bosons) have mass, but neither are considered matter either.[98] However, while these quanta are not considered matter, they do contribute to the total mass of atoms, subatomic particles, and all systems that contain them.[99][100]

See also

[edit]|

Antimatter Cosmology

|

Dark matter

Philosophy

|

Other

|

References

[edit]- ^ a b c R. Penrose (1991). "The mass of the classical vacuum". In S. Saunders; H.R. Brown (eds.). The Philosophy of Vacuum. Oxford University Press. pp. 21–26. ISBN 978-0-19-824449-3.

- ^ "Matter (physics)". McGraw-Hill's Access Science: Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Online. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "RHIC Scientists Serve Up "Perfect" Liquid" (Press release). Brookhaven National Laboratory. 18 April 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- ^ P. Davies (1992). The New Physics: A Synthesis. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-43831-5.

- ^ Gerard't Hooft (1997). In search of the ultimate building blocks. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-521-57883-7.

- ^ a b c d e Bernard Pullman (2001). The Atom in the History of Human Thought. Oxford University Press. pp. 77–84. ISBN 978-0-19-515040-7.

- ^ a b Jeaneane D. Fowler (2002). Perspectives of reality: an introduction to the philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 99–115. ISBN 978-1-898723-93-6.

- ^ J. Olmsted; G. M. Williams (1996). Chemistry: The Molecular Science (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8151-8450-8.

- ^ a b Davies, P. C. W. (1979). The Forces of Nature. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-521-22523-6.

- ^ a b Weinberg, S. (1998). The Quantum Theory of Fields. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-55002-4.

- ^ Masujima, M. (2008). Path Integral Quantization and Stochastic Quantization. Springer. p. 103. ISBN 978-3-540-87850-6.

- ^ Hale, Bob (19 September 2013). Necessary Beings: An Essay on Ontology, Modality, and the Relations Between Them. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191648342. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Chemical Substance". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01039

- ^ "2.1: Pure Substances and Mixtures". Chemistry LibreTexts. 15 March 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Hunter, Lawrence E. (13 January 2012). The Processes of Life: An Introduction to Molecular Biology. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262299947. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018.

- ^

G.F. Barker (1870). "Divisions of matter". A text-book of elementary chemistry: theoretical and inorganic. John F Morton & Co. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4460-2206-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ M. de Podesta (2002). Understanding the Properties of Matter (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-415-25788-6.

- ^

B. Povh; K. Rith; C. Scholz; F. Zetsche; M. Lavelle (2004). "Part I: Analysis: The building blocks of matter". Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts (4th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-20168-7.

Ordinary matter is composed entirely of first-generation particles, namely the u and d quarks, plus the electron and its neutrino.

- ^ a b B. Carithers; P. Grannis (1995). "Discovery of the Top Quark" (PDF). Beam Line. 25 (3): 4–16.

- ^

Tsan, Ung Chan (2006). "What Is a Matter Particle?" (PDF). International Journal of Modern Physics E. 15 (1): 259–272. Bibcode:2006IJMPE..15..259C. doi:10.1142/S0218301306003916. S2CID 121628541.

(From Abstract:) Positive baryon numbers (A>0) and positive lepton numbers (L>0) characterize matter particles while negative baryon numbers and negative lepton numbers characterize antimatter particles. Matter particles and antimatter particles belong to two distinct classes of particles. Matter-neutral particles are particles characterized by both zero baryon number and zero lepton number. This third class of particles includes mesons formed by a quark and an antiquark pair (a pair of matter particle and antimatter particle) and bosons which are messengers of known interactions (photons for electromagnetism, W and Z bosons for the weak interaction, gluons for the strong interaction). The antiparticle of a matter particle belongs to the class of antimatter particles, the antiparticle of an antimatter particle belongs to the class of matter particles.

- ^ D. Green (2005). High PT physics at hadron colliders. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-83509-1.

- ^ L. Smolin (2007). The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next. Mariner Books. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-618-91868-3.

- ^ The W boson mass is 80.398 GeV; see Figure 1 in C. Amsler; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: The Mass and Width of the W Boson" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1): 1. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. hdl:1854/LU-685594.

- ^ I.J.R. Aitchison; A.J.G. Hey (2004). Gauge Theories in Particle Physics. CRC Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7503-0864-9.

- ^ B. Povh; K. Rith; C. Scholz; F. Zetsche; M. Lavelle (2004). Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts. Springer. p. 103. ISBN 978-3-540-20168-7.

- ^ A.M. Green (2004). Hadronic Physics from Lattice QCD. World Scientific. p. 120. ISBN 978-981-256-022-3.

- ^ T. Hatsuda (2008). "Quark–gluon plasma and QCD". In H. Akai (ed.). Condensed matter theories. Vol. 21. Nova Publishers. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-60021-501-8.

- ^ K.W. Staley (2004). "Origins of the Third Generation of Matter". The Evidence for the Top Quark. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-521-82710-2.

- ^

Y. Ne'eman; Y. Kirsh (1996). The Particle Hunters (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-521-47686-7.

[T]he most natural explanation to the existence of higher generations of quarks and leptons is that they correspond to excited states of the first generation, and experience suggests that excited systems must be composite

- ^ S.M. Walker; A. King (2005). What is Matter?. Lerner Publications. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8225-5131-7.

- ^ J.Kenkel; P.B. Kelter; D.S. Hage (2000). Chemistry: An Industry-based Introduction with CD-ROM. CRC Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-56670-303-1.

All basic science textbooks define matter as simply the collective aggregate of all material substances that occupy space and have mass or weight.

- ^ K.A. Peacock (2008). The Quantum Revolution: A Historical Perspective. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-313-33448-1.

- ^ M.H. Krieger (1998). Constitutions of Matter: Mathematically Modeling the Most Everyday of Physical Phenomena. University of Chicago Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-226-45305-7.

- ^ S.M. Caroll (2004). Spacetime and Geometry. Addison Wesley. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-8053-8732-2.

- ^

P. Davies (1992). The New Physics: A Synthesis. Cambridge University Press. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-521-43831-5.

Matter fields: the fields whose quanta describe the elementary particles that make up the material content of the Universe (as opposed to the gravitons and their supersymmetric partners).

- ^ C. Amsler; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Reviews of Particle Physics: Quarks" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1–5): 1. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. hdl:1854/LU-685594.

- ^ "Dark Energy Dark Matter". NASA Science: Astrophysics. 5 June 2015.

- ^ Persic, Massimo; Salucci, Paolo (1 September 1992). "The baryon content of the Universe". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 258 (1): 14P – 18P. arXiv:astro-ph/0502178. Bibcode:1992MNRAS.258P..14P. doi:10.1093/mnras/258.1.14P. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 17945298.

- ^ Satz, H.; Redlich, K.; Castorina, P. (2009). "The Phase Diagram of Hadronic Matter". The European Physical Journal C. 59 (1): 67–73. arXiv:0807.4469. Bibcode:2009EPJC...59...67C. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-008-0795-z. S2CID 14503972.

- ^ Menezes, Débora P. (23 April 2016). "Modelling Hadronic Matter". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 706 (3) 032001. Bibcode:2016JPhCS.706c2001M. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/706/3/032001.

- ^ H.S. Goldberg; M.D. Scadron (1987). Physics of Stellar Evolution and Cosmology. Taylor & Francis. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-677-05540-4.

- ^ H.S. Goldberg; M.D. Scadron (1987). Physics of Stellar Evolution and Cosmology. Taylor & Francis. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-677-05540-4.

- ^ J.-P. Luminet; A. Bullough; A. King (1992). Black Holes. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-521-40906-3.

- ^ A. Bodmer (1971). "Collapsed Nuclei". Physical Review D. 4 (6): 1601. Bibcode:1971PhRvD...4.1601B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.4.1601.

- ^ E. Witten (1984). "Cosmic Separation of Phases". Physical Review D. 30 (2): 272. Bibcode:1984PhRvD..30..272W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.30.272.

- ^ C. Amsler; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: Leptons" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1–5): 1. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. hdl:1854/LU-685594.

- ^ C. Amsler; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: Neutrinos Properties" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1–5): 1. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. hdl:1854/LU-685594.

- ^ P.J. Collings (2002). "Chapter 1: States of Matter". Liquid Crystals: Nature's Delicate Phase of Matter. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08672-9.

- ^ D.H. Trevena (1975). "Chapter 1.2: Changes of phase". The Liquid Phase. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-85109-031-3.

- ^ National Research Council (US) (2006). Revealing the hidden nature of space and time. National Academies Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-309-10194-3.

- ^ Tsan, U.C. (2012). "Negative Numbers And Antimatter Particles". International Journal of Modern Physics E. 21 (1): 1250005–1–1250005–23. Bibcode:2012IJMPE..2150005T. doi:10.1142/S021830131250005X.

(From Abstract:) Antimatter particles are characterized by negative baryonic number A or/and negative leptonic number L. Materialization and annihilation obey conservation of A and L (associated to all known interactions)

- ^ Smorra C.; et al. (20 October 2017). "A parts-per-billion measurement of the antiproton magnetic moment". Nature. 550 (7676): 371–374. Bibcode:2017Natur.550..371S. doi:10.1038/nature24048. PMID 29052625.

- ^ Tsan, Ung Chan (2013). "Mass, Matter Materialization, Mattergenesis and Conservation of Charge". International Journal of Modern Physics E. 22 (5): 1350027. Bibcode:2013IJMPE..2250027T. doi:10.1142/S0218301313500274.

(From Abstract:) Matter conservation melans conservation of baryonic number A and leptonic number L, A and L being algebraic numbers. Positive A and L are associated to matter particles, negative A and L are associated to antimatter particles. All known interactions do conserve matter

- ^ J.P. Ostriker; P.J. Steinhardt (2003). "New Light on Dark Matter". Science. 300 (5627): 1909–13. arXiv:astro-ph/0306402. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1909O. doi:10.1126/science.1085976. PMID 12817140. S2CID 11188699.

- ^ K. Pretzl (2004). "Dark Matter, Massive Neutrinos and Susy Particles". Structure and Dynamics of Elementary Matter. Walter Greiner. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-4020-2446-7.

- ^ K. Freeman; G. McNamara (2006). "What can the matter be?". In Search of Dark Matter. Birkhäuser Verlag. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-387-27616-8.

- ^ J.C. Wheeler (2007). Cosmic Catastrophes: Exploding Stars, Black Holes, and Mapping the Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-521-85714-7.

- ^ J. Gribbin (2007). The Origins of the Future: Ten Questions for the Next Ten Years. Yale University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-300-12596-2.

- ^ P. Schneider (2006). Extragalactic Astronomy and Cosmology. Springer. p. 4, Fig. 1.4. ISBN 978-3-540-33174-2.

- ^ T. Koupelis; K.F. Kuhn (2007). In Quest of the Universe. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 492; Fig. 16.13. ISBN 978-0-7637-4387-1.

- ^ M.H. Jones; R.J. Lambourne; D.J. Adams (2004). An Introduction to Galaxies and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 21; Fig. 1.13. ISBN 978-0-521-54623-2.

- ^ a b c D. Majumdar (2007). Dark matter – possible candidates and direct detection. arXiv:hep-ph/0703310. Bibcode:2008pahh.book..319M.

- ^ K.A. Olive (2003). "Theoretical Advanced Study Institute lectures on dark matter". arXiv:astro-ph/0301505.

- ^ K.A. Olive (2009). "Colliders and Cosmology". European Physical Journal C. 59 (2): 269–295. arXiv:0806.1208. Bibcode:2009EPJC...59..269O. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-008-0738-8. S2CID 15421431.

- ^ J.C. Wheeler (2007). Cosmic Catastrophes. Cambridge University Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-521-85714-7.

- ^ L. Smolin (2007). The Trouble with Physics. Mariner Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-618-91868-3.

- ^ P.M. Chaikin; T.C. Lubensky (2000). Principles of Condensed Matter Physics. Cambridge University Press. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-521-79450-3.

- ^ W. Greiner (2003). W. Greiner; M.G. Itkis; G. Reinhardt; M.C. Güçlü (eds.). Structure and Dynamics of Elementary Matter. Springer. p. xii. ISBN 978-1-4020-2445-0.

- ^ P. Sukys (1999). Lifting the Scientific Veil: Science Appreciation for the Nonscientist. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8476-9600-0.

- ^ B. Povh; K. Rith; C. Scholz; F. Zetsche; M. Lavelle (2004). "Fundamental constituents of matter". Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts (4th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-20168-7.

- ^ von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999). Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 181. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

- ^ S. Toulmin; J. Goodfield (1962). The Architecture of Matter. University of Chicago Press. pp. 48–54.

- ^ Discussed by Aristotle in Physics, esp. book I, but also later; as well as Metaphysics I–II.

- ^ For a good explanation and elaboration, see R.J. Connell (1966). Matter and Becoming. Priory Press.

- ^

H.G. Liddell; R. Scott; J.M. Whiton (1891). A lexicon abridged from Liddell & Scott's Greek–English lexicon. Harper and Brothers. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ R. Descartes (1644). "The Principles of Human Knowledge". Principles of Philosophy I. p. 53.

- ^ though even this property seems to be non-essential (René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy II [1644], "On the Principles of Material Things", no. 4.)

- ^ R. Descartes (1644). "The Principles of Human Knowledge". Principles of Philosophy I. pp. 8, 54, 63.

- ^ D.L. Schindler (1986). "The Problem of Mechanism". In D.L. Schindler (ed.). Beyond Mechanism. University Press of America.

- ^ E.A. Burtt, Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Science (Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, 1954), 117–118.

- ^ J.E. McGuire and P.M. Heimann, "The Rejection of Newton's Concept of Matter in the Eighteenth Century", The Concept of Matter in Modern Philosophy ed. Ernan McMullin (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1978), 104–118 (105).

- ^ Isaac Newton, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, trans. A. Motte, revised by F. Cajori (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1934), pp. 398–400. Further analyzed by Maurice A. Finocchiaro, "Newton's Third Rule of Philosophizing: A Role for Logic in Historiography", Isis 65:1 (Mar. 1974), pp. 66–73.

- ^ Isaac Newton, Optics, Book III, pt. 1, query 31.

- ^ McGuire and Heimann, 104.

- ^ a b N. Chomsky (1988). Language and problems of knowledge: the Managua lectures (2nd ed.). MIT Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-262-53070-5.

- ^ McGuire and Heimann, 113.

- ^ M. Wenham (2005). Understanding Primary Science: Ideas, Concepts and Explanations (2nd ed.). Paul Chapman Educational Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-4129-0163-5.

- ^

J.C. Maxwell (1876). Matter and Motion. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-486-66895-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ T.H. Levere (1993). "Introduction". Affinity and Matter: Elements of Chemical Philosophy, 1800–1865. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-2-88124-583-1.

- ^ G.F. Barker (1870). "Introduction". A Text Book of Elementary Chemistry: Theoretical and Inorganic. John P. Morton and Company. p. 2.

- ^ J.J. Thomson (1909). "Preface". Electricity and Matter. A. Constable.

- ^ O.W. Richardson (1914). "Chapter 1". The Electron Theory of Matter. The University Press.

- ^ M. Jacob (1992). The Quark Structure of Matter. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-3687-8.

- ^ V. de Sabbata; M. Gasperini (1985). Introduction to Gravitation. World Scientific. p. 293. ISBN 978-9971-5-0049-8.

- ^ The history of the concept of matter is a history of the fundamental length scales used to define matter. Different building blocks apply depending upon whether one defines matter on an atomic or elementary particle level. One may use a definition that matter is atoms, or that matter is hadrons, or that matter is leptons and quarks depending upon the scale at which one wishes to define matter. B. Povh; K. Rith; C. Scholz; F. Zetsche; M. Lavelle (2004). "Fundamental constituents of matter". Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts (4th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-20168-7.

- ^ J. Allday (2001). Quarks, Leptons and the Big Bang. CRC Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7503-0806-9.

- ^ B.A. Schumm (2004). Deep Down Things: The Breathtaking Beauty of Particle Physics. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8018-7971-5.

- ^ See, for example, M. Jibu; K. Yasue (1995). Quantum Brain Dynamics and Consciousness. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-55619-183-1., B. Martin (2009). Nuclear and Particle Physics (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-470-74275-4. and K.W. Plaxco; M. Gross (2006). Astrobiology: A Brief Introduction. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8018-8367-5.

- ^ P.A. Tipler; R.A. Llewellyn (2002). Modern Physics. Macmillan. pp. 89–91, 94–95. ISBN 978-0-7167-4345-3.

- ^ P. Schmüser; H. Spitzer (2002). "Particles". In L. Bergmann; et al. (eds.). Constituents of Matter: Atoms, Molecules, Nuclei. CRC Press. pp. 773 ff. ISBN 978-0-8493-1202-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Lillian Hoddeson; Michael Riordan, eds. (1997). The Rise of the Standard Model. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57816-5.

- Timothy Paul Smith (2004). "The search for quarks in ordinary matter". Hidden Worlds. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05773-6.

- Harald Fritzsch (2005). Elementary Particles: Building blocks of matter. World Scientific. p. 1. Bibcode:2005epbb.book.....F. ISBN 978-981-256-141-1.

- Bertrand Russell (1992). "The philosophy of matter". A Critical Exposition of the Philosophy of Leibniz (Reprint of 1937 2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-415-08296-9.

- Stephen Toulmin and June Goodfield, The Architecture of Matter (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962).

- Richard J. Connell, Matter and Becoming (Chicago: The Priory Press, 1966).

- Ernan McMullin, The Concept of Matter in Greek and Medieval Philosophy (Notre Dame, Indiana: Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 1965).

- Ernan McMullin, The Concept of Matter in Modern Philosophy (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1978).

External links

[edit]- Visionlearning Module on Matter

- Matter in the universe How much Matter is in the Universe?

- NASA on superfluid core of neutron star

- Matter and Energy: A False Dichotomy – Conversations About Science with Theoretical Physicist Matt Strassler

Matter

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Properties

Classical Definition

In classical physics, matter is defined as any substance that possesses mass and occupies a finite volume of space, making it detectable through sensory perception or physical interaction. This conceptualization emphasizes matter's tangible nature, distinguishing it from abstract or non-material entities. For instance, everyday objects such as a wooden chair (solid), a glass of water (liquid), or the air in a room (gas) exemplify matter in its common forms, each exhibiting measurable mass and spatial extent. Unlike energy, which classical physics treats as the capacity for work or motion without inherent mass or volume—such as the kinetic energy of a moving object or heat transfer—matter maintains its identity through interactions. Key properties include inertia, the resistance to changes in motion proportional to its mass, as articulated in Newton's first law of motion; impenetrability, whereby two portions of matter cannot coexist in the same spatial point simultaneously; and divisibility, allowing matter to be subdivided into smaller units down to atoms in early atomic models like those proposed by John Dalton. These attributes underpin the mechanical behavior of matter in classical frameworks.[11][12][13] Historically, the classical understanding traces back to Aristotle's hylomorphism, in which matter (hylē) represents pure potentiality—the underlying substratum capable of receiving form (morphē) to become actualized substances—without independent existence or qualities of its own. As described in Aristotle's Physics and Metaphysics, matter persists through change as the indeterminate principle that form shapes into specific entities, such as bronze as potential statue. This philosophical foundation influenced subsequent classical views, evolving toward empirical models in the Scientific Revolution. This intuitive, macroscopic perspective laid the groundwork for later refinements in quantum mechanics.[14]Particle Physics Definition

In particle physics, matter is understood through the lens of quantum field theory as being composed exclusively of fermions, which are elementary particles characterized by half-integer spin values such as and that adhere to the Pauli exclusion principle, preventing two identical fermions from occupying the same quantum state simultaneously.[15] This principle, a cornerstone of quantum mechanics, ensures the stability and structure of matter by dictating how fermions interact and arrange in systems like atomic orbitals.[15] Fermions are categorized into two main families: quarks and leptons, both of which carry specific quantum numbers, including spin, charge, and, for quarks, color charge, that define their roles in the fundamental interactions.[16] Baryonic matter, which constitutes the ordinary matter observed in everyday phenomena, consists primarily of baryons—composite particles formed from three quarks bound together by the strong nuclear force.[17] Protons and neutrons, the key building blocks of atomic nuclei, exemplify these baryons: a proton comprises two up quarks and one down quark, while a neutron consists of one up quark and two down quarks, with their stability arising from the confinement of quarks within color-neutral combinations.[17] This three-quark structure distinguishes baryons from other hadrons and underpins the composition of all visible matter in the universe.[18] In the Standard Model of particle physics, the fundamental fermions are organized into three generations, but the first generation provides the essential constituents of stable baryonic matter.[16] The quarks in this generation are the up quark (with charge ) and the down quark (with charge ), while the leptons include the electron (charge -1) and the electron neutrino (neutral).[16] These particles, all fermions obeying the Pauli exclusion principle, form the protons, neutrons, and electrons that assemble into atoms.[18] In stark contrast, bosons—particles with integer spin, such as photons, gluons, and W/Z bosons—mediate the electromagnetic, strong, and weak forces but do not contribute to the material substance of matter itself.[15]Relativistic and Cosmological Perspectives

In the framework of special relativity, Albert Einstein established the mass-energy equivalence principle, expressed by the equation , where is energy, is rest mass, and is the speed of light.[19] This relation demonstrates that matter possesses intrinsic energy equivalent to its mass, blurring the classical distinction between the two and allowing matter to convert into other forms of energy under certain conditions.[19] Extending to general relativity, matter's energy content, including its rest mass, contributes to the stress-energy tensor , which sources the curvature of spacetime via Einstein's field equations . The stress-energy tensor encapsulates the distribution of mass, energy, momentum, and stress within matter fields, dictating how they influence gravitational fields and geodesic motion. Consequently, concentrations of matter, such as stars or galaxies, curve spacetime, manifesting as the gravitational attraction observed in the universe. In cosmology, matter plays a central role in the universe's composition and evolution within the Lambda cold dark matter (ΛCDM) model. As of 2024, observations indicate that ordinary (baryonic) matter constitutes approximately 5% of the total energy density, while dark matter accounts for about 27%, yielding a total matter fraction of roughly 32%.[20] These proportions are derived from measurements of the cosmic microwave background and baryon acoustic oscillations, with the total matter density parameter .[20] The remaining ~68% is attributed to dark energy, which drives the accelerated expansion.[20] The early universe transitioned through distinct eras dominated by radiation and matter following the Big Bang. During the radiation-dominated era, the energy density was governed by relativistic particles and photons, but matter domination began around 51,000 years after the Big Bang, when the matter density surpassed that of radiation at redshift .[21] This shift marked a pivotal point in cosmic expansion, slowing the rate compared to the prior era and enabling the growth of large-scale structures through gravitational instability.[21]Composition and Structure

Atomic and Molecular Level

Matter at the atomic and molecular level consists of atoms, which serve as the fundamental building blocks of all ordinary matter. Each atom comprises a dense central nucleus containing protons—positively charged particles—and neutrons, which are electrically neutral and contribute to the atom's mass.[22] Surrounding the nucleus are electrons, negatively charged particles that occupy probabilistic orbitals, determining the atom's chemical behavior through their arrangement and interactions.[23] The number of protons defines the element, while the balance between protons and electrons maintains electrical neutrality in isolated atoms.[24] The periodic table organizes all known chemical elements based on increasing atomic number, which is the count of protons in the nucleus and uniquely identifies each element.[25] This classification reveals periodic trends in chemical properties, such as reactivity and valence, arising from the electron configurations in outer shells; for instance, elements in the same group exhibit similar bonding tendencies due to comparable numbers of valence electrons.[26] These patterns enable predictions of how elements combine to form compounds, underpinning chemistry's foundational principles.[25] Isotopes are variants of the same element with identical atomic numbers but differing numbers of neutrons, affecting atomic mass without altering chemical properties.[27] Stable isotopes, like carbon-12 with six protons and six neutrons, do not undergo radioactive decay and thus contribute to the long-term stability of matter in biological and geological systems.[28] In contrast, unstable isotopes such as carbon-14, with six protons and eight neutrons, decay over time, releasing radiation and playing roles in processes like radiometric dating, though they represent a minor fraction in natural matter.[27] At the molecular level, atoms combine through chemical bonds to form molecules, exhibiting emergent properties distinct from individual atoms. Covalent bonds involve the sharing of electron pairs between atoms, as in diatomic oxygen (O₂), fostering strong, directional connections in nonmetals.[29] Ionic bonds result from the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions, typically formed by electron transfer from metals to nonmetals, yielding crystalline solids like sodium chloride (NaCl).[30] Metallic bonds feature delocalized electrons shared among metal atoms, enabling high electrical conductivity and malleability in substances like copper.[31] A key example is water (H₂O), where polar covalent bonds between oxygen and hydrogen atoms create a molecule with partial charges—oxygen slightly negative and hydrogens positive—due to oxygen's higher electronegativity, leading to unique properties like hydrogen bonding and solvent capabilities.[29]Subatomic Particles

Subatomic particles are the fundamental building blocks of atoms, consisting primarily of protons, neutrons, and electrons, which together determine the structure and properties of matter. These particles interact through fundamental forces to form stable atomic nuclei and electron clouds, enabling the formation of elements and compounds. Protons and neutrons reside in the nucleus, while electrons occupy orbitals around it, with their charges and masses dictating electromagnetic interactions and nuclear stability. The proton is a positively charged subatomic particle with a charge of , where is the elementary charge of approximately C, and a mass of approximately kg.[32] Protons define the atomic number of an element, which corresponds to the number of protons in the nucleus and thus determines the element's chemical identity and position in the periodic table.[22] Their positive charge repels other protons but is overcome by the strong nuclear force, allowing multiple protons to coexist in the nucleus. The neutron is an electrically neutral subatomic particle with a mass of approximately kg, slightly greater than that of the proton.[33] Neutrons contribute to the stability of the atomic nucleus by providing additional binding through the strong nuclear force, which counteracts the electromagnetic repulsion between protons without adding to the positive charge.[34] The number of neutrons can vary in isotopes of the same element, affecting nuclear stability and enabling phenomena like radioactive decay. The electron is a negatively charged subatomic particle with a charge of and a mass of approximately kg, making it about 1/1836 the mass of a proton.[35] Electrons govern chemical bonding by occupying outer orbitals and participating in electromagnetic interactions, which dictate the reactivity of atoms and the conduction of electricity in materials.[22] Their arrangement in electron shells determines the valence and thus the chemical properties of elements. Within the nucleus, protons and neutrons—collectively known as nucleons—are bound together by the strong nuclear force, one of the four fundamental interactions, which acts at very short ranges (about 10^{-15} m) to overcome proton repulsion and maintain nuclear integrity.[34] The weak nuclear force, another fundamental interaction, plays a role in processes like beta decay, where a neutron transforms into a proton (or vice versa), emitting an electron or positron and altering the atomic number.[36] Protons and neutrons themselves are composite particles made up of more fundamental quarks, though their substructure is explored in greater detail elsewhere.[37]Fundamental Constituents

In the Standard Model of particle physics, all ordinary matter is composed of elementary fermions known as quarks and leptons.[16] These particles are the fundamental building blocks, with quarks participating in the strong nuclear force and leptons not.[16] There are twelve such fermions in total, organized into three generations or families, each containing two quarks and two leptons, with masses increasing across generations.[38] Quarks come in six flavors: up, down, charm, strange, top, and bottom.[38] The first generation includes the light up quark (mass approximately 2.2 MeV/c², electric charge +2/3) and down quark (mass approximately 4.7 MeV/c², charge -1/3), which are stable within composite particles and constitute the protons and neutrons of atomic nuclei.[39] The second generation features the charm quark (mass ~1.27 GeV/c², charge +2/3) and strange quark (mass ~94 MeV/c², charge -1/3), while the third includes the heavy top quark (mass ~173 GeV/c², charge +2/3) and bottom quark (mass ~4.18 GeV/c², charge -1/3); the latter two are short-lived, decaying rapidly due to their high masses.[39] Leptons also number six: the charged electron (mass 0.511 MeV/c², charge -1), muon (mass 105.7 MeV/c², charge -1), and tau (mass 1.777 GeV/c², charge -1), paired with their neutral counterparts—the electron neutrino, muon neutrino, and tau neutrino (with upper mass limits of <0.0008 MeV/c² for electron neutrino, <0.19 MeV/c² for muon neutrino, and <18 MeV/c² for tau neutrino, all at 90% CL).[40] Only the first-generation leptons (electron and electron neutrino) are stable and prevalent in ordinary matter, while the muon and tau decay into lighter particles on timescales of microseconds to femtoseconds.[38] Neutrinos interact only via the weak force and gravity, making them notoriously difficult to detect.[16] The three generations exhibit a pattern of increasing mass, with only the first generation appearing stably in everyday matter due to the instability of heavier particles.[16] Quarks, unlike leptons, carry "color charge" and are subject to color confinement: they cannot exist in isolation but are perpetually bound within color-neutral hadrons, such as baryons (e.g., protons, composed of three quarks) or mesons, through the exchange of gluons mediated by quantum chromodynamics (QCD).[41] This confinement arises from a linearly increasing potential between quarks, ensuring that attempts to separate them produce new quark-antiquark pairs instead.[41]| Generation | Quarks (Flavor, Approx. Mass in MeV/c², Charge) | Leptons (Type, Approx. Mass in MeV/c², Charge) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Up (2.2, +2/3); Down (4.7, -1/3) | Electron (0.511, -1); Electron Neutrino (<8×10^{-7}, 0) |

| 2 | Charm (1273, +2/3); Strange (94, -1/3) | Muon (105.7, -1); Muon Neutrino (<0.19, 0) |

| 3 | Top (172600, +2/3); Bottom (4183, -1/3) | Tau (1777, -1); Tau Neutrino (<18, 0) |