Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Humoral immune deficiency

View on Wikipedia| Humoral immune deficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

| B cells and antibody | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Sinusitis[1] |

| Causes | Absent B cells(primary),[2][3] Multiple myeloma(secondary)[4] |

| Diagnostic method | B cell count, Family medical history[5][6] |

| Treatment | Immunoglobulin replacement therapy[5] |

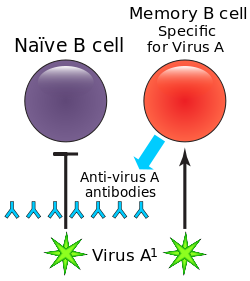

Humoral immune deficiencies are conditions which cause impairment of humoral immunity, which can lead to immunodeficiency. It can be mediated by insufficient number or function of B cells, the plasma cells they differentiate into, or the antibody secreted by the plasma cells.[7] The most common such immunodeficiency is inherited selective IgA deficiency, occurring between 1 in 100 and 1 in 1000 persons, depending on population. They are associated with increased vulnerability to infection, but can be difficult to detect (or asymptomatic) in the absence of infection.[citation needed]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Signs/symptoms of humoral immune deficiency depend on the cause, but generally include signs of infection such as:[1]

Causes

[edit]Cause of this deficiency is divided into primary and secondary:

- Primary the International Union of Immunological Societies classifies primary immune deficiencies of the humoral system as follows:[3][2]

- Absent B cells with a resultant severe reduction of all types of antibody: X-linked agammaglobulinemia (btk deficiency, or Bruton's agammaglobulinemia), μ-Heavy chain deficiency, l 5 deficiency, Igα deficiency, BLNK deficiency, thymoma with immunodeficiency

- B cells low but present, but with reduction in 2 or more isotypes (usually IgG & IgA, sometimes IgM): common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), ICOS deficiency, CD19 deficiency, TACI (TNFRSF13B) deficiency, BAFF receptor deficiency.

- Normal numbers of B cells with decreased IgG and IgA and increased IgM: Hyper-IgM syndromes

- Normal numbers of B cells with isotype or light chain deficiencies: heavy chain deletions, kappa chain deficiency, isolated IgG subclass deficiency, IgA with IgG subsclass deficiency, selective immunoglobulin A deficiency

- Transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy (THI)

- Secondary secondary (or acquired) forms of humoral immune deficiency are mainly due to hematopoietic malignancies and infections that disrupt the immune system:[4]

Diagnosis

[edit]

In terms of diagnosis of humoral immune deficiency depends upon the following:[5][6]

- Measure serum immunoglobulin levels

- B cell count

- Family medical history

Treatment

[edit]Treatment for B cell deficiency (humoral immune deficiency) depends on the cause, however generally the following applies:[5]

- Treatment of infection (antibiotics)

- Surveillance for malignancies

- Immunoglobulin replacement therapy

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b N. Franklin Adkinson Jr.; Bochner, Bruce S.; Burks, Wesley; Busse, William W.; Holgate, Stephen T. (2013-11-01). Middleton's Allergy: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1134. ISBN 9780323085939.

- ^ a b "Pure B-Cell Disorders: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 2017-01-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Notarangelo L, Casanova JL, Conley ME, et al. (2006). "Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update from the International Union of Immunological Societies Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Classification Committee Meeting in Budapest, 2005". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 117 (4): 883–96. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1347. PMID 16680902.

- ^ a b Page 432, Chapter 22, Table 22.1 in: Jones, Jane; Bannister, Barbara A.; Gillespie, Stephen H. (2006). Infection: Microbiology and Management. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2665-6.

- ^ a b c d Fried, Ari J.; Bonilla, Francisco A. (2009-07-01). "Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management of Primary Antibody Deficiencies and Infections". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (3): 396–414. doi:10.1128/CMR.00001-09. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 2708392. PMID 19597006.

- ^ a b Cecil, Russell La Fayette; Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (2012-01-01). Goldman's Cecil Medicine, Expert Consult Premium Edition -- Enhanced Online Features and Print, Single Volume,24: Goldman's Cecil Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1618. ISBN 978-1437716047.

- ^ Pieper, Kathrin; Grimbacher, Bodo; Eibel, Hermann (2013-04-01). "B-cell biology and development". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 131 (4): 959–971. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.046. ISSN 0091-6749. PMID 23465663.

Further reading

[edit]- Ahn, Sam; Cunningham-Rundles, Charlotte (2017-05-11). "Role of B cells in common variable immune deficiency". Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 5 (5): 557–564. doi:10.1586/eci.09.43. ISSN 1744-666X. PMC 2922984. PMID 20477641.

- Honjo, Tasuku; Reth, Michael; Radbruch, Andreas; Alt, Frederick (2014-10-09). Molecular Biology of B Cells. Elsevier. ISBN 9780123984906.