Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nephrology

View on Wikipedia| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names |

|

Occupation type | Specialty |

Activity sectors | Medicine |

| Description | |

Education required |

|

Fields of employment | Hospitals, Clinics |

Nephrology is a specialty for both adult internal medicine and pediatric medicine that concerns the study of the kidneys, specifically normal kidney function (renal physiology) and kidney disease (renal pathophysiology), the preservation of kidney health, and the treatment of kidney disease, from diet and medication to renal replacement therapy (dialysis and kidney transplantation). The word "renal" is an adjective meaning "relating to the kidneys", and its roots are French or late Latin. Whereas according to some opinions, "renal" and "nephro-" should be replaced with "kidney" in scientific writings such as "kidney medicine" (instead of "nephrology") or "kidney replacement therapy", other experts have advocated preserving the use of renal and nephro- as appropriate including in "nephrology" and "renal replacement therapy", respectively.[1]

Nephrology also studies systemic conditions that affect the kidneys, such as diabetes and autoimmune disease; and systemic diseases that occur as a result of kidney disease, such as renal osteodystrophy and hypertension. A physician who has undertaken additional training and become certified in nephrology is called a nephrologist.

Etymology

[edit]The term "nephrology" was first used in about 1960, according to the French néphrologie proposed by Jean Hamburger in 1953, from the Greek νεφρός, nephrós (kidney). Before then, the specialty was usually referred to as "kidney medicine".[2]

Scope

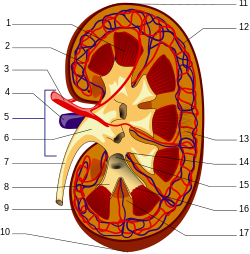

[edit] A human kidney (click on image for description). | |

| System | Urinary |

|---|---|

| Significant diseases | Hypertension, Kidney cancer |

| Significant tests | Kidney biopsy, Urinalysis |

| Specialist | Nephrologist |

| Glossary | Glossary of medicine |

Nephrology concerns the diagnosis and treatment of kidney diseases, including electrolyte disturbances and hypertension, and the care of those requiring renal replacement therapy, including dialysis and renal transplant patients.[3][4]

The word dialysis is from the mid-19th century: via Latin from the Greek word dialusis; from dialuein (split, separate), from dia (apart) and luein (set free). In other words, dialysis replaces the primary (excretory) function of the kidney, which separates (and removes) excess toxins and water from the blood, placing them in the urine.[5]

Many diseases affecting the kidney are systemic disorders not limited to the organ itself, and may require special treatment. Examples include acquired conditions such as systemic vasculitides (e.g. ANCA vasculitis) and autoimmune diseases (e.g. lupus), as well as congenital or genetic conditions such as polycystic kidney disease.[6]

Patients are referred to nephrology specialists after a urinalysis, for various reasons, such as acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, hematuria, proteinuria, kidney stones, hypertension, and disorders of acid/base or electrolytes.[7]

Nephrologist

[edit]A nephrologist is a physician who specializes in the care and treatment of kidney disease. Nephrology requires additional training to become an expert with advanced skills. Nephrologists may provide care to people without kidney problems and may work in general/internal medicine, transplant medicine, immunosuppression management, intensive care medicine, clinical pharmacology, perioperative medicine, or pediatric nephrology.[8]

Nephrologists may further sub-specialise in dialysis, kidney transplantation, home therapies (home dialysis), cancer-related kidney diseases (onco-nephrology), structural kidney diseases (uro-nephrology), procedural nephrology or other non-nephrology areas as described above.

Procedures a nephrologist may perform include native kidney and transplant kidney biopsy, dialysis access insertion (temporary vascular access lines, tunnelled vascular access lines, peritoneal dialysis access lines), fistula management (angiographic or surgical fistulogram and plasty), and bone biopsy.[9] Bone biopsies are now unusual.

Training

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

India

To become a nephrologist in India, one has to complete an MBBS (5 and 1/2 years) degree, followed by an MD/DNB (3 years) either in medicine or paediatrics, followed by a DM/DNB (3 years) course in either nephrology or paediatric nephrology.

Australia and New Zealand

[edit]Nephrology training in Australia and New Zealand typically includes completion of a medical degree (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery: 4–6 years), internship (1 year), Basic Physician Training (3 years minimum), successful completion of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians written and clinical examinations, and Advanced Physician Training in Nephrology (3 years). The training pathway is overseen and accredited by the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, though the application process varies across states. Completion of a post-graduate degree (usually a PhD) in a nephrology research interest (3–4 years) is optional but increasingly common. Finally, many Australian and New Zealand nephrologists participate in career-long professional and personal development through bodies such as the Australian and New Zealand Society of Nephrology and the Transplant Society of Australia and New Zealand.

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, nephrology (often called renal medicine) is a subspecialty of general medicine. A nephrologist has completed medical school, foundation year posts (FY1 and FY2) and core medical training (CMT), specialist training (ST) and passed the Membership of the Royal College of Physicians (MRCP) exam before competing for a National Training Number (NTN) in renal medicine. The typical Specialty Training (when they are called a registrar, or an ST) is five years and leads to a Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT) in both renal medicine and general (internal) medicine. In those five years, they usually rotate yearly between hospitals in a region (known as a deanery). They are then accepted on to the Specialist Register of the General Medical Council (GMC). Specialty trainees often interrupt their clinical training to obtain research degrees (MD/PhD). After achieving CCT, the registrar (ST) may apply for a permanent post as Consultant in Renal Medicine. Subsequently, some Consultants practice nephrology alone. Others work in this area, and in Intensive Care (ICU), or General (Internal) or Acute Medicine.

United States

[edit]Nephrology training can be accomplished through one of two routes. The first path way is through an internal medicine pathway leading to an Internal Medicine/Nephrology specialty, and sometimes known as "adult nephrology". The second pathway is through Pediatrics leading to a speciality in Pediatric Nephrology. In the United States, after medical school adult nephrologists complete a three-year residency in internal medicine followed by a two-year (or longer) fellowship in nephrology. Complementary to an adult nephrologist, a pediatric nephrologist will complete a three-year pediatric residency after medical school or a four-year Combined Internal Medicine and Pediatrics residency. This is followed by a three-year fellowship in Pediatric Nephrology. Once training is satisfactorily completed, the physician is eligible to take the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) or American Osteopathic Board of Internal Medicine (AOBIM) nephrology examination. Nephrologists must be approved by one of these boards. To be approved, the physician must fulfill the requirements for education and training in nephrology in order to qualify to take the board's examination. If a physician passes the examination, then he or she can become a nephrology specialist. Typically, nephrologists also need two to three years of training in an ACGME or AOA accredited fellowship in nephrology. Nearly all programs train nephrologists in continuous renal replacement therapy; fewer than half in the United States train in the provision of plasmapheresis.[10] Only pediatric trained physicians are able to train in pediatric nephrology, and internal medicine (adult) trained physicians may enter general (adult) nephrology fellowships.

Diagnosis

[edit]History and physical examination are central to the diagnostic workup in nephrology. The history typically includes the present illness, family history, general medical history, diet, medication use, drug use and occupation. The physical examination typically includes an assessment of volume state, blood pressure, heart, lungs, peripheral arteries, joints, abdomen and flank. A rash may be relevant too, especially as an indicator of autoimmune disease.

Examination of the urine (urinalysis) allows a direct assessment for possible kidney problems, which may be suggested by appearance of blood in the urine (hematuria), protein in the urine (proteinuria), pus cells in the urine (pyuria) or cancer cells in the urine. A 24-hour urine collection used to be used to quantify daily protein loss (see proteinuria), urine output, creatinine clearance or electrolyte handling by the renal tubules. It is now more common to measure protein loss from a small random sample of urine.

Basic blood tests can be used to check the concentration of hemoglobin, white count, platelets, sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, urea, creatinine, albumin, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase and parathyroid hormone (PTH) in the blood. All of these may be affected by kidney problems. The serum creatinine concentration is the most important blood test as it is used to estimate the function of the kidney, called the creatinine clearance or estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

It is a good idea for patients with longterm kidney disease to know an up-to-date list of medications, and their latest blood tests, especially the blood creatinine level. In the United Kingdom, blood tests can monitored online by the patient, through a website called RenalPatientView.

More specialized tests can be ordered to discover or link certain systemic diseases to kidney failure such as infections (hepatitis B, hepatitis C), autoimmune conditions (systemic lupus erythematosus, ANCA vasculitis), paraproteinemias (amyloidosis, multiple myeloma) and metabolic diseases (diabetes, cystinosis).

Structural abnormalities of the kidneys are identified with imaging tests. These may include Medical ultrasonography/ultrasound, computed axial tomography (CT), scintigraphy (nuclear medicine), angiography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

In certain circumstances, less invasive testing may not provide a certain diagnosis. Where definitive diagnosis is required, a biopsy of the kidney (renal biopsy) may be performed. This typically involves the insertion, under local anaesthetic and ultrasound or CT guidance, of a core biopsy needle into the kidney to obtain a small sample of kidney tissue. The kidney tissue is then examined under a microscope, allowing direct visualization of the changes occurring within the kidney. Additionally, the pathology may also stage a problem affecting the kidney, allowing some degree of prognostication. In some circumstances, kidney biopsy will also be used to monitor response to treatment and identify early relapse. A transplant kidney biopsy may also be performed to look for rejection of the kidney.

Treatment

[edit]Treatments in nephrology can include medications, blood products, surgical interventions (urology, vascular or surgical procedures), renal replacement therapy (dialysis or kidney transplantation) and plasma exchange. Kidney problems can have significant impact on quality and length of life, and so psychological support, health education and advanced care planning play key roles in nephrology.

Chronic kidney disease is typically managed with treatment of causative conditions (such as diabetes), avoidance of substances toxic to the kidneys (nephrotoxins like radiologic contrast and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), antihypertensives, diet and weight modification and planning for end-stage kidney failure. Impaired kidney function has systemic effects on the body. An erythropoetin stimulating agent (ESA) may be required to ensure adequate production of red blood cells, activated vitamin D supplements and phosphate binders may be required to counteract the effects of kidney failure on bone metabolism, and blood volume and electrolyte disturbance may need correction. Diuretics (such as furosemide) may be used to correct fluid overload, and alkalis (such as sodium bicarbonate) can be used to treat metabolic acidosis.

Auto-immune and inflammatory kidney disease, such as vasculitis or transplant rejection, may be treated with immunosuppression. Commonly used agents are prednisone, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, everolimus, thymoglobulin and sirolimus. Newer, so-called "biologic drugs" or monoclonal antibodies, are also used in these conditions and include rituximab, basiliximab and eculizumab. Blood products including intravenous immunoglobulin and a process known as plasma exchange can also be employed.

When the kidneys are no longer able to sustain the demands of the body, end-stage kidney failure is said to have occurred. Without renal replacement therapy, death from kidney failure will eventually result. Dialysis is an artificial method of replacing some kidney function to prolong life. Renal transplantation replaces kidney function by inserting into the body a healthier kidney from an organ donor and inducing immunologic tolerance of that organ with immunosuppression. At present, renal transplantation is the most effective treatment for end-stage kidney failure although its worldwide availability is limited by lack of availability of donor organs. Generally speaking, kidneys from living donors are 'better' than those from deceased donors, as they last longer.

Most kidney conditions are chronic conditions and so long term followup with a nephrologist is usually necessary. In the United Kingdom, care may be shared with the patient's primary care physician, called a General Practitioner (GP).

Organizations

[edit]The world's first society of nephrology was the French 'Societe de Pathologie Renale'. Its first president was Jean Hamburger, and its first meeting was in Paris in February 1949. In 1959, Hamburger also founded the 'Société de Néphrologie', as a continuation of the older society. It is now called Francophone Society of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation (SFNDT). The second society of nephrologists, the UK Kidney Association (UKKA) was founded in 1950, originally named the Renal Association. Its first president was Arthur Osman and met for the first time, in London, on 30 March 1950. The Società di Nefrologia Italiana was founded in 1957 and was the first national society to incorporate the phrase nephrologia (or nephrology) into its name.

The word 'nephrology' appeared for the first time in a conference, on 1–4 September 1960 at the "Premier Congrès International de Néphrologie" in Evian and Geneva, the first meeting of the International Society of Nephrology (ISN, International Society of Nephrology). The first day (1.9.60) was in Geneva and the next three (2–4.9.60) were in Evian, France. The early history of the ISN is described by Robinson and Richet[11] in 2005 and the later history by Barsoum[12] in 2011. The ISN is the largest global society representing medical professionals engaged in advancing kidney care worldwide.[citation needed] It has an international office in Brussels, Belgium.[13]

In the US, founded in 1964, the National Kidney Foundation is a national organization representing patients and professionals who treat kidney diseases. Founded in 1966, the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) is the world's largest professional society devoted to the study of kidney disease. The American Nephrology Nurses' Association (ANNA), founded in 1969, promotes excellence in and appreciation of nephrology nursing to make a positive difference for patients with kidney disease. The American Association of Kidney Patients (AAKP) is a non-profit, patient-centric group focused on improving the health and well-being of CKD and dialysis patients. The National Renal Administrators Association (NRAA), founded in 1977, is a national organization that represents and supports the independent and community-based dialysis providers. The American Kidney Fund directly provides financial support to patients in need, as well as participating in health education and prevention efforts. ASDIN (American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology) is the main organization of interventional nephrologists. Other organizations include CIDA, VASA etc. which deal with dialysis vascular access. The Renal Support Network (RSN) is a nonprofit, patient-focused, patient-run organization that provides non-medical services to those affected by chronic kidney disease (CKD).

In the United Kingdom, UK National Kidney Federation and Kidney Care UK (previously known as British Kidney Patient Association, BKPA)[14] represent patients, and the UK Kidney Association used to represent renal physicians and worked closely with a previous NHS policy directive called a National Service Framework for kidney disease.

References

[edit]- ^ Kalantar-Zadeh, Kamyar; McCullough, Peter A.; Agarwal, Sanjay Kumar; Beddhu, Srinivasan; Boaz, Mona; Bruchfeld, Annette; Chauveau, Philippe; Chen, Jing; De Sequera, Patricia; Gedney, Nieltje; Golper, Thomas A.; Gupta, Malini; Harris, Tess; Hartwell, Lori; Liakopoulos, Vassilios; Kopple, Joel D.; Kovesdy, Csaba P.; MacDougall, Iain C.; Mann, Johannes F. E.; Molony, Donald; Norris, Keith C.; Perlmutter, Jeffrey; Rhee, Connie M.; Riella, Leonardo V.; Weisbord, Steven D.; Zoccali, Carmine; Goldsmith, David (Mar 13, 2021). "Nomenclature in nephrology: preserving 'renal' and 'nephro' in the glossary of kidney health and disease". J. Nephrol. 34 (3): 639–648. doi:10.1007/s40620-021-01011-3. PMC 8192439. PMID 33713333.

- ^ Professor Priscilla Kincaid-Smith, nephrologist Archived 2016-10-03 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Academy of Science, Interview by Dr Max Blythe in 1998.

- ^ "Nephrology Specialty Description". American Medical Association.

- ^ "Nephrology". American College of Physicians. 15 May 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ "Dialysis". nhs.uk. 2017-10-19. Archived from the original on 2022-09-14. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "Kidney failure (ESRD) - Symptoms, causes and treatment options | American Kidney Fund". www.kidneyfund.org. 2021-11-17. Archived from the original on 2022-09-14. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "5 Reasons Why You May be Referred to a Nephrologist - Durham Nephrology Associates, PA". 2021-09-15. Archived from the original on 2022-09-14. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ "International Society of Nephrology". Kidney International. 64 (1): 387–389. 2003-07-01. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.t01-7-00001.x. ISSN 0085-2538.

- ^ "Bone lesion biopsy: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2025-05-19.

- ^ Berns JS; O'Neill WC (2008). "Performance of procedures by nephrologists and nephrology fellows at U.S. nephrology training programs". Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 3 (4): 941–7. doi:10.2215/CJN.00490108. PMC 2440278. PMID 18417748.

- ^ "Kidney International - A Forty Year History 1960-2000". Archived from the original on 2011-08-10. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ "International Society of Nephrology". Kidney International. 64 (1): 387–389. 2003-07-01. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.t01-7-00001.x. ISSN 0085-2538.

- ^ "Homepage". Kidney Care UK. Archived from the original on 2017-06-11. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

External links

[edit]- International Society of Nephrology (ISN) Archived 2012-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Nephromap Archived 2022-08-14 at the Wayback Machine