Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

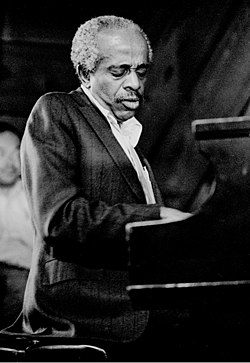

Barry Harris

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Barry Doyle Harris (December 15, 1929 – December 8, 2021) was an American jazz pianist, bandleader, composer, arranger, and educator. He was an exponent of the bebop style.[1][2] Influenced by Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell,[3] Harris in turn influenced and mentored bebop musicians including Donald Byrd, Paul Chambers, Curtis Fuller, Joe Henderson, Charles McPherson, and Michael Weiss.[4]

Early life

[edit]

Harris was born on December 15, 1929, in Detroit, Michigan, to Melvin Harris and Bessie as the fourth of their five children.[3][1] Harris took piano lessons from his mother at the age of four.[3] His mother, a church pianist, asked him if he was interested in playing church music or jazz, and he chose the latter.[3] In his teens, he performed for dances at his high school, local clubs and ballrooms.[5]

Harris's family home became a popular jam session destination for young jazz musicians including Roland Hanna, Sonny Red, Donald Byrd, and Harold McKenny. Many Motown pioneers, including Berry Gordy, were friends of Harris in his youth.[6]

Career

[edit]1946–1960: Detroit

[edit]Harris, who described Bud Powell's style as the "epitome" of jazz, learned bebop largely by ear,[5] starting with Powell's recording of "Webb City" with Sonny Stitt and Fats Navarro. Harris made one of his first recordings in Toledo, Ohio, in 1950, and made another in Detroit in 1952 with trombonist Frank Rosolino.[7] Harris said in a later interview that he also recorded a musical for Willie "Face" Smith around this time, but the album was lost.[8]

Harris remained in Detroit through the 1950s and worked with Miles Davis, Sonny Stitt, and Thad Jones,[3] and substituted for Junior Mance in Gene Ammons' band. In 1956, he toured briefly with Max Roach,[3] after Richie Powell, the band's pianist and younger brother of Bud Powell, died in a car crash.[9] Harris left Detroit in 1960 to tour with the Cannonball Adderley quintet.[4]

1960–1982: New York

[edit]Harris performed with Cannonball Adderley's quintet and on television with them.[9] After moving to New York City, he worked as an educator and performed with Dexter Gordon, Illinois Jacquet, Yusef Lateef and Hank Mobley.[9] Harris was a sideman on Lee Morgan's famous album The Sidewinder and returned to recording as leader following his move to New York.[10]

Between 1965 and 1969, Harris worked extensively with Coleman Hawkins at the Village Vanguard[11] and was one of the few musicians who continued to play bebop in Harlem during the shift toward jazz fusion in the late 1960s.[6]

During the 1970s, Harris lived with Monk at the Weehawken, New Jersey, home of the jazz patron Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter.[12] He substituted for Monk in rehearsals at the New York Jazz Repertory Company in 1974.[13]

In Japan, Harris performed at the Yubin Chokin concert hall in Tokyo over two days, and his performances were recorded and compiled into an album released by Xanadu Records.[11]

1982–2021: Jazz educator

[edit]Between 1982 and 1987, he was responsible for the Jazz Cultural Theatre on 8th Avenue in New York. As a co-manager with promoters Jim Harrison and Frank Fuentes, Harris brought jazz artists to the club, including Jaki Byard, Bill Hardman, Junior Cook, Vernel Fournier, Walter Bishop Jr., Michael Weiss, and Chris Anderson, before closing the club due to increased rent.[14]

From the 1990s onwards, Harris collaborated with Howard Rees on videos and workbooks documenting his harmonic and improvisational systems and teaching process.[15][16] He held music workshop sessions in New York City for vocalists, students of piano and other instruments.[17]

Harris received an honorary doctorate from Northeastern University and a joint award with Oscar Peterson and Hank Jones from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.[6]

Harris appeared in the 1989 documentary film Thelonious Monk: Straight, No Chaser (made by Clint Eastwood's production company), performing duets with Tommy Flanagan. In 1999, he was profiled in the film Barry Harris: Spirit of Bebop.[5][7]

Although Harris took his weekly workshops onto Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic,[4] he died from complications of the virus at a hospital in North Bergen, New Jersey, on December 8, 2021, a week before his 92nd birthday.[1][4] Harris taught his last music class less than three weeks before his death.[4]

Personal life

[edit]Harris married Christine Brown in 1953; they remained married until her death in 2017. He suffered a stroke in 1993, but was able to continue his career and play in public after recovering.[10]

Awards and honors

[edit]- 1989: NEA Jazz Master

- 1995: Doctor of Arts – Honorary Degree by Northwestern University

- 1995: Honorary Jazz Award by the House of Representatives[18][19]

- 1995: Presidential Award, Recognition of Dedication and Commitment to the Pursuance of Artistic Excellence in Jazz Performance and Education

- 1997: Dizzy Gillespie Achievement Award

- 1997: Recognition of Excellence in Jazz Music and Education

- 1998: Congratulatory Letter as a Jazz Musician and Educator by the U.S. White House

- 1998: Lifetime Achievements Award for Contributions to the Music World from the National Association of Negro Musicians

- 2000: American Jazz Hall of Fame for Lifetime Achievements & Contributions to the World of Jazz

Discography

[edit]As leader

[edit]| Recording date | Title | Label | Year released | Personnel/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958–07 | Breakin' It Up | Argo | 1959 | Trio, with William Austin (bass), Frank Gant (drums) |

| 1960–05 | Barry Harris at the Jazz Workshop | Riverside | 1960 | Trio, with Sam Jones (bass), Louis Hayes (drums); in concert |

| 1960–12 | Listen to Barry Harris | Riverside | 1961 | Solo piano |

| 1960–12, 1961-01 |

Preminado | Riverside | 1961 | One track solo piano; other tracks trio, with Joe Benjamin (bass), Elvin Jones (drums) |

| 1961–09 | Newer Than New | Riverside | 1961 | Quintet, with Lonnie Hillyer (trumpet), Charles McPherson (alto sax), Ernie Farrow (bass), Clifford Jarvis (drums) |

| 1962–05, 1962-08 |

Chasin' the Bird | Riverside | 1962 | Trio, with Bob Cranshaw, (bass), Clifford Jarvis (drums) |

| 1967–04 | Luminescence! | Prestige | 1967 | Sextet, with Slide Hampton (trombone), Junior Cook (tenor sax), Pepper Adams (baritone sax), Bob Cranshaw (bass), Lenny McBrowne (drums) |

| 1968–06 | Bull's Eye! | Prestige | 1968 | Some tracks trio, with Paul Chambers (bass), Billy Higgins (drums); some tracks quintet, with Kenny Dorham (trumpet), Charles McPherson (tenor sax), Pepper Adams (baritone sax) added |

| 1969–11 | Magnificent! | Prestige | 1970 | Trio, with Ron Carter (bass), Leroy Williams (drums) |

| 1972 | Vicissitudes | MPS | 1975 | Trio, with George Duvivier (bass), Leroy Williams (drums) |

| 1975–06 | Barry Harris Plays Tadd Dameron | Xanadu | 1975 | Trio, with Gene Taylor (bass), Leroy Williams (drums) |

| 1976–04 | Live in Tokyo | Xanadu | 1976 | Trio, with Sam Jones (bass), Leroy Williams (drums); in concert |

| 1978–01 | Barry Harris Plays Barry Harris | Xanadu | 1978 | Trio, with George Duvivier (bass), Leroy Williams (drums) |

| 1979–09 | The Bird of Red and Gold | Xanadu | 1982 | Solo piano; Harris also sings on one track |

| 1984–03 | For the Moment | Uptown | 1985 | Trio, with Rufus Reid (bass), Leroy Williams (drums); in concert |

| 1990–03 | Live at Maybeck Recital Hall, Volume Twelve | Concord | 1991 | Solo piano; in concert |

| 1991 | Post Master Class Concert | Blue Jack Jazz Records | 2005 | Trio, with Jacques Schols (bass), Eric Ineke (drums); in concert |

| 1991–09 | Confirmation | Candid | 1992 | Quartet, with Kenny Barron (piano), Ray Drummond (bass), Ben Riley (drums); in concert |

| 1991–12 | Barry Harris in Spain | Nuba | 1992 | Trio, with Chuck Israels (bass), Leroy Williams (drums); in concert |

| 1995–05 | Live at "Dug" | Enja | 1997 | Trio, with Kunimitsu Inaba (bass), Fumio Watanabe (drums); in concert |

| 1996–10 | First Time Ever | Alfa Jazz | 1997 | Trio, with George Mraz (bass), Leroy Williams (drums) |

| 1998–04 | I'm Old Fashioned | Alfa Jazz | 1998 | Most tracks trio, with George Mraz (bass), Leroy Williams (drums); two tracks with Barry Harris Family Chorus (vocals) added |

| 2000–06 | The Last Time I Saw Paris | Venus | 2000 | Trio, with George Mraz (bass), Leroy Williams (drums) |

| 2002–08 | Live in New York | Reservoir | 2003 | Quintet, with Charles Davis (tenor sax), Roni Ben-Hur (guitar), Paul West (bass), Leroy Williams (drums); in concert |

| 2004–05 | Live from New York!, Vol. One | Lineage | 2006 | Trio, with John Webber (bass), Leroy Williams (drums); in concert |

| 2009–11 | Live in Rennes | Plus Loin | 2010 | Trio, with Mathias Allamane (bass), Philippe Soirat (drums); in concert |

Source:[20]

As sideman

[edit]|

With Al Cohn

With Dexter Gordon

With Johnny Griffin

With Coleman Hawkins

With Buck Hill

With Sam Jones

With Yusef Lateef

With Charles McPherson

With Hank Mobley

With Lee Morgan

With Sonny Red With Red Rodney

With Sonny Stitt

|

With others

|

See also

[edit]- Bebop scale or 6th Diminished Scale, jazz education tool pioneered by Harris

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Russonello, Giovanni (December 9, 2021). "Barry Harris, Pianist and Devoted Scholar of Bebop, Dies at 91". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Milkowski, Bill (1998). "Barry Harris: Young-hearted elder". Jazz Times. Updated May 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Larkin, Colin (1992). The Guinness Who's Who of Jazz (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. pp. 190–91. ISBN 0-85112-580-8.

- ^ a b c d e Stryker, Mark (December 8, 2021). "Barry Harris, beloved jazz pianist devoted to bebop, dies at 91". NPR. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c Barry Harris: Spirit of Bebop. Efor Films. 2004.

- ^ a b c Dwyer, Tom (March 16, 2006). "Barry Harris in New York". All About Jazz. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "Barry Harris Spirit of Bebop". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Schermer, Victor L. (December 11, 2021). "Barry Harris: Iconic Jazz Pianist and Keeper of the Flame". All About Jazz. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c Barry Kernfeld, ed. (2002). The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz Second edition. London, England: Macmillan. p. 177. ISBN 033369189X.

- ^ a b Schudel, Matt (December 10, 2021). "Barry Harris, jazz pianist who kept the spirit of bebop alive, dies at 91". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Thomas, Greg (July 16, 2012). "Bebop legend Barry Harris set to burn up Village Vanguard with 2-week gig". New York Daily News. New York. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ Watrous, Peter (May 28, 1994). "Be-Bop's Generous Romantic", The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2008. "Mr. Harris moved to New York in the early 1960s and became friends with Thelonious Monk and Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, Mr. Monk's patron. Eventually, Mr. Harris moved to her estate in Weehawken, N.J., where he still lives."

- ^ Carr, Ian; Digby Fairweather; Brian Priestley (1988). Jazz The Essential Companion. New York: Prentice Hall Press. ISBN 0-13-509274-4.

- ^ Myers, Marc (April 28, 2017). "Jazz news: Jazz Cultural Theatre Lives!". JazzWax. Retrieved February 24, 2024 – via All About Jazz.

- ^ "Evolutionary Voicings, Part 1 – Howard Rees' Jazz Workshops". Jazzworkshops.com. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ "About Howard Rees – Howard Rees' Jazz Workshops". Jazzworkshops.com. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ "Barry Harris Residency April 7 through 10". Brown.edu. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ "Recognition Awards to Barry Harris for Outstanding Devotion to Music and Education". Barryharris.com. 2014. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ "Barry Harris facts, information, pictures". Encyclopedia.com. May 18, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ "Barry Harris Discography". Jazzdisco.org. Retrieved December 20, 2018.