Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

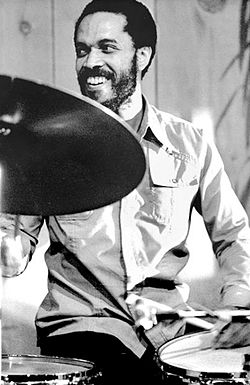

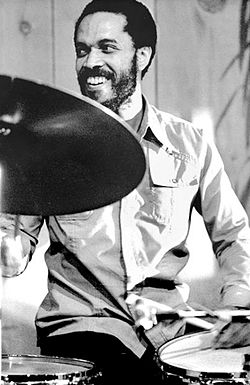

Billy Higgins

View on WikipediaKey Information

Billy Higgins (October 11, 1936 – May 3, 2001) was an American jazz drummer. He played mainly free jazz and hard bop.[1]

Biography

[edit]Higgins was born in Los Angeles, California, United States.[2] Higgins played on Ornette Coleman's first records, beginning in 1958.[3] He then freelanced extensively with hard bop and other post-bop players, including Donald Byrd, Dexter Gordon, Grant Green, Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, Don Cherry, Paul Horn, Milt Jackson, Jackie McLean, Pat Metheny, Hank Mobley, Thelonious Monk, Lee Morgan, David Murray, Art Pepper, Sonny Rollins, Mal Waldron, and Cedar Walton.[3] He was one of the house drummers for Blue Note Records and played on dozens of Blue Note albums of the 1960s.[3] He also collaborated with composer La Monte Young and guitarist Sandy Bull.

In his career, Higgins played on more than 700 recordings, including recordings of rock and funk. He appeared as a jazz drummer in the 1986 movie Round Midnight and the 2001 movie Southlander.

In 1989, Higgins cofounded a cultural center, The World Stage, in Los Angeles to encourage and promote younger jazz musicians. The center provides workshops in performance and writing, as well as concerts and recordings. Higgins also taught in the jazz studies program at the University of California, Los Angeles.[4]

Billy Higgins died of kidney and liver failure on May 3, 2001, at a hospital in Inglewood, California.[4]

Discography

[edit]As leader

[edit]- 1979: Soweto (Red)

- 1979: The Soldier (Timeless, [1981])

- 1980: Once More (Red)

- 1984: Mr. Billy Higgins (Evidence)

- 1980-86: Bridgework (Contemporary)

- 1994: ¾ for Peace (Red)

- 1997: Billy Higgins Quintet (Evidence)

- 2001: The Best of Summer Nights at Moca (Exodus)

As a sideman

[edit]With Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt

[edit]- God Bless Jug and Sonny (Prestige, 1973 [2001])

- Left Bank Encores (Prestige, 1973 [2001])

With Chris Anderson

[edit]- Blues One (DIW, 1991)

With Gary Bartz

[edit]- Libra (Milestone, 1968)

With Paul Bley

[edit]- Live at the Hilcrest Club 1958 (Inner City, 1958 [1976])

- Coleman Classics Volume 1 (Improvising Artists, 1958 [1977])

With Sandy Bull

[edit]- Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo (Vanguard, 1963)

- Inventions (Vanguard, 1965)

With Jaki Byard

[edit]- On the Spot! (Prestige, 1967)

With Donald Byrd

[edit]- Royal Flush (Blue Note, 1961)

- Free Form (Blue Note, 1962)

- Blackjack (Blue Note, 1967)

- Slow Drag (Blue Note, 1967)

With Joe Castro

[edit]- Groove Funk Soul (Atlantic, 1959)

With Don Cherry

[edit]- Brown Rice (EMI, 1975)

- Art Deco (A&M, 1988)

With Sonny Clark

[edit]- Leapin' and Lopin' (Blue Note, 1961)

With George Coleman

[edit]- Amsterdam After Dark (Timeless, 1979)

With Ornette Coleman

[edit]- Something Else!!!! (Contemporary, 1958)

- The Shape of Jazz to Come (Atlantic, 1959)

- Change of the Century (Atlantic, 1959)

- The Art of the Improvisers (Atlantic, 1959)

- To Whom Who Keeps a Record (Warner, 1959–60)

- Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation (Atlantic, 1961)

- Twins (Atlantic, 1961)

- Science Fiction (Columbia, 1971)

- Broken Shadows (Columbia, 1971–1972 [1982])

- The Complete Science Fiction Sessions (Columbia, 1971–1972 [2000])

- In All Languages (Caravan of Dreams, 1987)

With John Coltrane

[edit]- Like Sonny (Roulette, 1960)

With Junior Cook

[edit]- Somethin's Cookin' (Muse, 1981)

With Bill Cosby

[edit]- Hello, Friend: To Ennis with Love (Verve, 1997)

With Stanley Cowell

[edit]- Regeneration (Strata East, 1976)

With Ray Drummond

[edit]- The Essence (DMP, 1985)

With Teddy Edwards

[edit]- Teddy Edwards at Falcon's Lair (MetroJazz, 1958)

- Sunset Eyes (Pacific Jazz, 1960)

- Teddy's Ready! (Contemporary, 1960)

- Nothin' But the Truth! (Prestige, 1966)

- Young at Heart (Storyville, 1979) with Howard McGhee

- Wise in Time (Storyville, 1979) with Howard McGhee

- Mississippi Lad (Verve/Gitanes, 1991)

- Tango in Harlem (Verve/Gitanes, 1994)

With Booker Ervin

[edit]- Tex Book Tenor (Blue Note, 1968)

With Art Farmer

[edit]- Homecoming (Mainstream, 1971)

- Yesterday's Thoughts (East Wind, 1975)

- To Duke with Love (East Wind, 1975)

- The Summer Knows (East Wind, 1976)

- Art Farmer Quintet at Boomers (East Wind, 1976)

With Curtis Fuller

[edit]- Smokin' (Mainstream, 1972)

With Stan Getz

[edit]- Cal Tjader-Stan Getz Sextet (1958, Fantasy) with Cal Tjader

With Dexter Gordon

[edit]- Go (Blue Note, 1962)

- A Swingin' Affair (Blue Note, 1962)

- Clubhouse (Blue Note, 1965 – released 1979)

- Gettin' Around (Blue Note, 1965)

- Tangerine (Prestige, 1972 [1975])

- Generation (Prestige, 1972)

- Something Different (SteepleChase, 1975 [1980])

- Bouncin' with Dex (SteepleChase, 1976)

- The Other Side of Round Midnight (Blue Note, 1985)

With Grant Green

[edit]- First Session (Blue Note, 1961)

- Goin' West (Blue Note, 1962)

- Feelin' the Spirit (Blue Note, 1962)

With Dodo Greene

[edit]- My Hour of Need (Blue Note, 1962)

With Charlie Haden

[edit]- Quartet West (Verve, 1986)

- Silence (Soul Note, 1987)

- The Private Collection (Naim, 1987-88 [2000])

- First Song (Soul Note, 1990 [1992])

With Slide Hampton

[edit]- Roots (Criss Cross, 1985)

With Herbie Hancock

[edit]- Takin' Off (Blue Note, 1962)

- Round Midnight (soundtrack) (Columbia, 1985)

With Barry Harris

[edit]- Bull's Eye! (Prestige, 1968)

With Eddie Harris

[edit]- The In Sound (Atlantic, 1965)

- Mean Greens (Atlantic, 1966)

- The Tender Storm (Atlantic, 1966)

- Excursions (Atlantic, 1966–73)

- How Can You Live Like That? (Atlantic, 1976)

With Johnny Hartman

[edit]- Today (Perception, 1972)

With Jimmy Heath

[edit]- Love and Understanding (Muse, 1973)

- The Time and the Place (Landmark, 1974 [1994])

- Picture of Heath (Xanadu, 1975)

With Joe Henderson

[edit]- Mirror Mirror (MPS, 1980)

With Andrew Hill

[edit]- Dance with Death (Blue Note, 1968 – not released until 1980)

With Christopher Hollyday

[edit]- Christopher Hollyday (BMG, 1989)

With Richard "Groove" Holmes

[edit]- Get Up & Get It! (Prestige, 1967)

With Paul Horn

[edit]- Something Blue (HiFi Jazz, 1960)

With Toninho Horta

[edit]- Once I Loved (Verve, 1992)

With Freddie Hubbard

[edit]- Bolivia (Music Master, 1991)

With Bobby Hutcherson

[edit]- Stick-Up (Blue Note, 1969)

- Solo / Quartet (Contemporary, 1982)

- Farewell Keystone (Theresa, 1982 [1988])

- Color Schemes (Landmark, 1985 [1986])

With J. J. Johnson

[edit]- Pinnacles (Milestone, 1980)

With Hank Jones and Dave Holland

[edit]- The Oracle (EmArcy, 1990)

With Sam Jones

[edit]- Seven Minds (East Wind Records, 1974)

- Cello Again (Xanadu, 1976)

- Something in Common (Muse, 1977)

With Clifford Jordan

[edit]- Soul Fountain (Vortex, 1966 [1970])

- Glass Bead Games (Strata-East, 1974)

- Night of the Mark VII (Muse, 1975)

- On Stage Vol. 1 (SteepleChase, 1975 [1977])

- On Stage Vol. 2 (SteepleChase, 1975 [1978])

- On Stage Vol. 3 (SteepleChase, 1975 [1979])

- Firm Roots (Steeplechase, 1975)

- The Highest Mountain (Steeplechase, 1975)

With Fred Katz

[edit]- Fred Katz and his Jammers (Decca, 1959)

With Steve Lacy

[edit]- Evidence (New Jazz, 1962) with Don Cherry

With Charles Lloyd

[edit]- Acoustic Masters I (Atlantic, 1993)

- Voice in the Night (ECM, 1999)

- The Water Is Wide (ECM, 2000)

- Hyperion with Higgins (ECM, 2001, released posthumously)

- Which Way Is East (ECM, 2004, released posthumously)

With Pat Martino

[edit]- The Visit! (Cobblestone, 1972) also released as Footprints

With Jackie McLean

[edit]- A Fickle Sonance (Blue Note, 1961)

- Let Freedom Ring Blue Note, 1962)

- Vertigo (Blue Note, 1962–63)

- Action Action Action (Blue Note, 1964)

- Consequence (Blue Note, 1965 [2005])

- New and Old Gospel (Blue Note, 1967)

With Charles McPherson

[edit]- The Quintet/Live! (Prestige, 1966)

- Horizons (Prestige, 1968)

- Today's Man (Mainstream, 1973)

With Pat Metheny

[edit]- Rejoicing (ECM, 1984)

With Blue Mitchell

[edit]- Bring It Home to Me (Blue Note, 1966)

With Red Mitchell

[edit]- Presenting Red Mitchell (Contemporary, 1957)

With Hank Mobley

[edit]- The Turnaround (Blue Note, 1965)

- Dippin' (Blue Note, 1965)

- A Caddy for Daddy (Blue Note, 1965)

- A Slice of the Top (Blue Note, 1966 [1979])

- Hi Voltage (Blue Note, 1967)

- Third Season (Blue Note, 1967)

- Far Away Lands (Blue Note, 1967)

- Reach Out! (Blue Note, 1968)

- Breakthrough! (Muse, 1972) with Cedar Walton

- Straight No Filter (Blue Note, 1964-66 [1980])

With Thelonious Monk

[edit]- Thelonious Monk at the Blackhawk (Riverside, 1960)

With Buddy Montgomery

[edit]- Ties of Love (Landmark, 1987)

- With Tete Montoliu

- Secret Love (Timeless, 1977)

- Live at the Keystone Corner (Timeless, 1979 [1981])

With Frank Morgan

[edit]- Easy Living (Contemporary, 1985)

- Lament (Contemporary, 1986)

- Bebop Lives! (Contemporary, 1987)

- Love, Lost & Found (Telarc, 1995)

With Lee Morgan

[edit]- The Sidewinder (Blue Note, 1963)

- Search for the New Land (Blue Note, 1964)

- The Rumproller (Blue Note, 1965)

- The Gigolo (Blue Note, 1965)

- Cornbread (Blue Note, 1965)

- Infinity (Blue Note, 1965 [1980])

- Delightfulee (Blue Note, 1966)

- Charisma (Blue Note, 1966)

- The Rajah (Blue Note, 1966 [1984])

- Sonic Boom (Blue Note, 1967 [1979])

- The Sixth Sense (Blue Note, 1967–68)

- The Procrastinator (Blue Note, 1967 [1978])

- Taru (Blue Note, 1968 [1980])

- Caramba! (Blue Note, 1968)

With Bheki Mseleku

[edit]- Star Seeding (Polygram Records, 1995)

With David Murray

[edit]- Live at Sweet Basil Volume 1 (Black Saint, 1984)

- Live at Sweet Basil Volume 2 (Black Saint, 1984)

With Horace Parlan

[edit]- Happy Frame of Mind (Blue Note, 1963)

With Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen

[edit]- Jaywalkin' (SteepleChase, 1975)

- Double Bass (SteepleChase, 1976) with Sam Jones

With Art Pepper

[edit]- So in Love (Artists House, 1979)

- Artworks (Galaxy, 1979 [1984])

- Landscape (Galaxy, 1979)

- Besame Mucho (JVC, 1979 [1981])

- Straight Life (Galaxy, 1979)

- Art 'n' Zoot (Pablo, 1981 [1995]) with Zoot Sims

With Dave Pike

[edit]- It's Time for Dave Pike (Riverside, 1961)

- Pike's Groove (Criss Cross Jazz, 1986) with Cedar Walton

With Jimmy Raney

[edit]- The Influence (Xanadu, 1975)

With Sonny Red

[edit]- Sonny Red (Mainstream, 1971)

With Freddie Redd

[edit]- Live at the Studio Grill (Triloka, 1990)

With Joshua Redman

[edit]- Wish (1993)

With Red Rodney

[edit]- The Red Tornado (Muse, 1975)

With Sonny Rollins

[edit]- Our Man in Jazz (RCA Victor, 1965)

- There Will Never Be Another You (recorded 1965 released 1978)

With Charlie Rouse

[edit]- Bossa Nova Bacchanal (Blue Note, 1965)

With Hilton Ruiz

[edit]- Piano Man (SteepleChase, 1975)

With Pharoah Sanders

[edit]- Rejoice (Theresa, 1981)

With Rob Schneiderman

[edit]- Smooth Sailing (Reservoir, 1990)

With John Scofield

[edit]- Works for Me (Verve, 2001)

With Shirley Scott

[edit]- One for Me (Strata-East, 1974)

With Archie Shepp

[edit]- Attica Blues (Impulse!, 1972)

With Sonny Simmons

[edit]- Rumasuma (Contemporary, 1969)

With James Spaulding

[edit]- James Spaulding Plays the Legacy of Duke Ellington (Storyville, 1977)

With Robert Stewart

[edit]- Judgement (World Stage, 1994 / Red Records, 1997)

- The Movement (Exodus, 2002)

With Sonny Stitt

[edit]- Blues for Duke (Muse, 1975 [1978])

With Idrees Sulieman

[edit]- Now Is the Time (SteepleChase, 1976)

With Ira Sullivan

[edit]- Peace (Galaxy, 1978)

- Multimedia (Galaxy, 1978 [1982])

With Sun Ra

[edit]- Somewhere Else (Rounder, 1988–89)

- Blue Delight (A&M, 1989)

With Cecil Taylor

[edit]- Jumpin' Punkins (Candid, 1961)

- New York City R&B (Candid, 1961)

With Lucky Thompson

[edit]- Goodbye Yesterday (Groove Merchant, 1973)

With the Timeless All Stars

[edit]- It's Timeless (Timeless, 1982)

- Timeless Heart (Timeless, 1983)

- Essence (Delos, 1986)

- Time for the Timeless All Stars (Early Bird, 1990)

With Bobby Timmons

[edit]- Soul Food (Prestige, 1966)

- Got to Get It! (Milestone, 1967)

With Charles Tolliver

[edit]- The New Wave in Jazz (Impulse!, 1965)

With Stanley Turrentine

[edit]- More Than a Mood (MusicMasters, 1992)

With Mal Waldron

[edit]- Up Popped the Devil (Enja, 1973)

- Like Old Times (RCA Victor, 1976)

- One Entrance, Many Exits (Palo Alto, 1982)

With Cedar Walton

[edit]- Cedar! (Prestige, 1967)

- Eastern Rebellion (Timeless, 1976) with George Coleman & Sam Jones

- The Pentagon (East Wind, 1976)

- Eastern Rebellion 2 (Timeless, 1977) with Bob Berg & Sam Jones

- First Set (SteepleChase, 1977 [1978])

- Second Set (SteepleChase, 1977 [1979])

- Third Set (SteepleChase, 1977 [1982])

- Eastern Rebellion 3 (Timeless, 1980) with Curtis Fuller, Bob Berg & Sam Jones

- The Maestro (Muse, 1981)

- Among Friends (Theresa, 1982 [1989])

- Eastern Rebellion 4 (Timeless, 1984) with Curtis Fuller, Bob Berg, Alfredo "Chocolate" Armenteros & David Williams

- Cedar's Blues (Red, 1985)

- The Trio 1 (Red, 1985)

- The Trio 2 (Red, 1985)

- The Trio 3 (Red, 1985)

- Cedar Walton (Timeless, 1985)

- Bluesville Time (Criss Cross Jazz, 1985)

- Cedar Walton Plays (Delos, 1986)

- As Long as There's Music (Muse, 1990 [1993])

- Mosaic (Music Masters, 1990 [1992]) as Eastern Rebellion

- Simple Pleasure (Music Masters, 1993) as Eastern Rebellion

- Manhattan Afternoon (Criss Cross Jazz, 1992 [1994])

- Just One of Those Nights: At the Village Vanguard (Music Masters, 1995) as Eastern Rebellion

With Don Wilkerson

[edit]- The Texas Twister (1960)

- Preach Brother! (1962)

With David Williams

[edit]- Up Front (Timeless, 1987)

With Jack Wilson

[edit]- Easterly Winds (Blue Note, 1967)

References

[edit]- ^ "Billy Higgins | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ James Nadal (ed.). "Billy Higgins". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on 2010-05-05. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

- ^ a b c Colin Larkin, ed. (1992). The Guinness Who's Who of Jazz (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 0-85112-580-8.

- ^ a b Ratliff, Ben (2001-05-04). "Billy Higgins, 64, Jazz Drummer With Melodic and Subtle Swing". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

External links

[edit]Billy Higgins

View on GrokipediaBiography

Early Life

Billy Higgins was born on October 11, 1936, in Los Angeles, California, into a working-class African American family. He spent his childhood in the Watts neighborhood of South Central Los Angeles, a vibrant yet challenging community marked by socioeconomic hardships common to many Black families in mid-20th-century urban America. Limited details are available about his immediate family, but the area provided a culturally rich backdrop for his formative years.[5][6] Higgins first encountered the drums at age 12, marking the beginning of his musical journey. Largely self-taught, he honed his skills by listening intently to phonograph records and immersing himself in the sounds of the local music scene around him.[2] The musical environment of Los Angeles during his youth was steeped in rhythm and blues and gospel traditions, which permeated neighborhood gatherings, churches, and informal performances. These influences surrounded Higgins, fostering his innate sense of rhythm and laying the groundwork for his future in music.[2]Professional Beginnings

Billy Higgins launched his professional music career at the age of 19 in 1955, immersing himself in the vibrant rhythm and blues scene of Los Angeles. He began performing with prominent R&B ensembles, including those led by pianist Amos Milburn and guitarist Bo Diddley, as well as vocalist Jimmy Witherspoon, providing steady backbeats on the trap set during live engagements. These early experiences in the city's bustling club circuit, such as local venues in the Central Avenue district, allowed Higgins to refine his technical proficiency and adaptability, essential for the demanding pace of R&B performances that often involved extended regional tours across California and the Southwest.[2][7][8] As the mid-1950s progressed, Higgins gradually transitioned from R&B toward jazz, drawn by the improvisational possibilities of the genre. He started collaborating with emerging West Coast jazz talents, including trumpeter Don Cherry—whom he had met during high school—and saxophonists James Clay and Walter Benton, participating in informal jam sessions and local gigs that showcased his evolving swing feel. By 1957, he joined bassist Red Mitchell's band for a brief stint, marking a pivotal step into more structured jazz settings while continuing to perform in Los Angeles clubs. These interactions honed his ability to support dynamic ensembles, blending the drive of R&B with jazz's rhythmic subtlety.[2][9] Higgins' initial recordings reflected this dual foundation, beginning with uncredited R&B tracks alongside Milburn and Witherspoon in the mid-1950s, which captured the energetic shuffle rhythms of the era. His early jazz sessions emerged around 1958, including house band work at the Oasis Club with saxophonist Eric Dolphy and trumpeter Lester Robertson, where they explored bebop expansions in a live context. These outings, though not widely documented on disc at the time, laid the groundwork for Higgins' reputation as a versatile drummer capable of bridging genres.[10][7]Association with Ornette Coleman

Billy Higgins first encountered Ornette Coleman in Los Angeles around 1958, during a period when Coleman was developing his innovative approach to jazz improvisation. Higgins, drawn to Coleman's unconventional style, joined rehearsals and quickly became part of the emerging quartet, which included trumpeter Don Cherry and bassist Charlie Haden. This collaboration marked a turning point for Higgins, shifting him from rhythm-and-blues sessions toward the avant-garde frontiers of free jazz.[11][1] Higgins' drumming provided the essential rhythmic foundation for Coleman's nascent harmolodics theory, which emphasized equal melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic contributions from all instruments. He participated in the landmark album Something Else!!!! (1958), Coleman's debut as a leader, where Higgins' dynamic, swinging patterns supported the group's exploration of collective improvisation on tracks like "Invisible" and "The Sphinx." The following year, Higgins appeared on The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959), delivering propulsive yet flexible grooves that anchored the quartet's boundary-pushing performances, including the iconic "Lonely Woman," allowing horns to venture freely while maintaining an underlying pulse.[12][13][14] In late 1959, Higgins relocated to New York City with Coleman's quartet, debuting at the Five Spot Café on November 17 amid intense scrutiny from the jazz community. The group's residency, which extended for several weeks, sparked significant backlash; established figures like Miles Davis and Coleman Hawkins openly criticized the music as discordant and unmusical, leading to heated debates and even physical altercations outside the venue. Despite the hostility, Higgins' steady, intuitive drumming helped sustain the quartet's cohesion during these pivotal performances, which solidified free jazz as a legitimate movement.[15][16][17] Higgins' contributions extended to advancing free improvisation techniques on drums, where he balanced traditional swing with spontaneous accents and textural shifts, freeing the rhythm section from strict timekeeping to engage in melodic dialogue. His approach on pieces like "Congeniality" from The Shape of Jazz to Come exemplified this, using cymbal washes and rim shots to punctuate the group's abstract explorations without imposing rigid structure. This role not only supported Coleman's vision but also influenced subsequent generations of improvising drummers.[18][19]Major Collaborations

Following his tenure with Ornette Coleman's groundbreaking free jazz ensemble, Billy Higgins established himself as one of the most sought-after drummers in jazz during the 1960s, freelancing extensively with leading hard bop figures on both recordings and tours. He provided dynamic propulsion on Dexter Gordon's seminal album Go! (1962), where his crisp, swinging rhythms supported Gordon's expansive tenor saxophone lines alongside pianist Sonny Clark and bassist Butch Warren.[20] Higgins also toured and recorded with Sonny Rollins in the early 1960s, notably contributing to the live album Our Man in Jazz (1962), captured at the Village Gate with Don Cherry on cornet and Bob Cranshaw on bass, showcasing his ability to navigate Rollins' intricate improvisations with elastic yet precise timekeeping.[21] Similarly, Higgins joined Thelonious Monk for a brief but impactful stint, appearing on the live recording At the Blackhawk (1960), where his subtle, interactive drumming complemented Monk's angular piano and the frontline of Charlie Rouse and Joe Gordon.[22] Higgins extended his reach into modal jazz through his work with Herbie Hancock, delivering elegant, flowing grooves on the album Takin' Off (1962), a Blue Note session featuring Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Dexter Gordon on tenor saxophone, and Butch Warren on bass, which included the hit "Watermelon Man."[2][23] In parallel, he ventured into avant-garde territory with Cecil Taylor, participating in the pianist's Candid Records sessions compiled on The Complete Nat Hentoff Sessions (1960–1961), where Higgins' adaptable percussion—often in trio or septet formats with Buell Neidlinger on bass and guests like Archie Shepp—provided a grounded yet exploratory foundation for Taylor's dense, percussive piano innovations.[24] Higgins maintained a long-standing musical friendship with saxophonist Charles Lloyd dating back to the mid-1950s, with intermittent gigging together in the early 1960s before Lloyd's quartet gained prominence; their partnership deepened in later decades through extensive tours and recordings, including the spiritually infused duo album Which Way Is East? (2001), which captured their profound rapport shortly before Higgins' death.[25] His stylistic range shone through in bebop contexts, such as on Hank Mobley's Hi Voltage (1967), where Higgins' buoyant, interactive playing energized Mobley's soulful tenor lines with pianist John Hicks and bassist Bob Cranshaw.[26] By the 1980s, Higgins explored fusion-tinged territories with guitarist Pat Metheny on Rejoicing (1984), a trio effort with Charlie Haden on bass that blended post-bop lyricism with subtle electric edges, highlighting Higgins' enduring versatility across jazz subgenres.[27]Later Career and Community Involvement

After nearly two decades of touring and residing in New York City, Billy Higgins converted to Islam in 1977 and returned to his native Los Angeles in 1978, where he continued to balance extensive session work with emerging educational efforts in the jazz community.[28][4][9] He remained in high demand as a sideman, contributing to numerous recordings across jazz styles while gradually shifting focus toward mentoring younger musicians through informal teaching and community programs.[2][25] In 1989, Higgins co-founded The World Stage, a cultural center in Leimert Park, alongside poet and activist Kamau Daáood, with the explicit aim of nurturing emerging jazz talent and promoting African American arts through performance and education.[29][2] The venue served as a vital hub for creative workshops, poetry readings, and jazz performances, filling a gap in accessible spaces for South Central Los Angeles' artistic community and emphasizing collective expression over commercial success.[30][31] Throughout the 1990s, Higgins maintained an active performance schedule, including notable collaborations with saxophonists David Murray and Pharoah Sanders that highlighted spiritual and communal themes in jazz.[6] For instance, he drummed on Murray's 1990 album Shoulders, contributing to its exploratory, ensemble-driven sound, and participated in live engagements with Sanders that evoked deep emotional and ritualistic improvisation.[19] These efforts underscored Higgins' commitment to jazz as a unifying, transformative force, often performed in intimate settings that fostered audience connection.[25] At The World Stage, Higgins spearheaded mentorship programs, particularly through weekly drum workshops that he led from the center's inception, drawing established artists to guide aspiring players.[30][32] These sessions, held on Monday nights, provided hands-on instruction for youth and adults alike, attracting talents such as pianist Billy Childs and emphasizing technical skill alongside cultural heritage.[4][32] By leveraging his reputation, Higgins ensured the workshops became a pipeline for new voices in jazz, reinforcing the center's role in sustaining the genre's vitality in Los Angeles.[31]Musical Style

Influences

Billy Higgins' drumming style was profoundly shaped by pioneering figures in modern jazz, particularly Kenny Clarke, whose minimalist approach to the ride cymbal emphasized implication over overt busyness, allowing other instruments to shine. Higgins admired Clarke's ability to do "very little" yet imply rich textures that enhanced ensemble sounds, a technique that informed his own restrained swing.[21] Similarly, Max Roach influenced Higgins through his melodic phrasing and forward momentum on the drums, blending swing-era precision with innovative expression that Higgins incorporated into his loose yet propulsive timekeeping.[6] Non-drummer musicians also played a key role in forming Higgins' rhythmic sensibility. Pianist Art Tatum's extraordinary precision and fluidity in complex rhythms captivated Higgins early on, providing a model for rhythmic accuracy and swing that transcended traditional drum set roles.[21] Through later collaborations with Charles Mingus, Higgins absorbed Mingus' intricate polyrhythms, which expanded his understanding of layered, interactive grooves beyond standard jazz swing.[7] Higgins began drumming at age 12 and, by age 19, played with R&B ensembles led by Amos Milburn and Bo Diddley in the vibrant Los Angeles music scene, absorbing energetic, shuffle-based patterns that contrasted with but complemented his emerging jazz foundation.[8][7] Affiliations with big bands such as Lionel Hampton's introduced him to swinging, dance-oriented rhythms with blues inflections, emphasizing ensemble drive and subtle fills.[7] Additionally, the diverse Central Avenue jazz and R&B milieu in Los Angeles exposed him to African-derived rhythms, which he later integrated via influences like Ed Blackwell's New Orleans second-line patterns and polyrhythmic layering.[6] Philosophically, Higgins drew from spiritual and improvisational ethos in jazz, prioritizing intuition and communal flow over rigid timekeeping. His tenure with Ornette Coleman's quartet in the late 1950s taught him to approach music with an "open heart," embracing freedom without judgment of "wrongs and rights," a mindset rooted in jazz's exploratory traditions.[33] This intuitive stance was deepened by his Islamic faith and mentorship roles, where he emphasized listening and spiritual connection in performance.[6]Technique and Innovations

Billy Higgins was renowned for his signature loose and intuitive drumming style, characterized by an elastic time feel that allowed for fluid free improvisation while maintaining an underlying pulse. This approach provided a flexible rhythmic foundation, enabling soloists to explore without rigid constraints, as exemplified in his work on Ornette Coleman's The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959).[34][6] Higgins innovated in his use of brushwork and cymbal sizzle to create textural support in avant-garde settings, particularly on Coleman recordings where he employed shimmering cymbal pulses and dancing snare accents to enhance atmospheric depth. His ride cymbal technique, often featuring riveted models for a cushioned, vibrant sizzle, contributed a "dancing momentum" that evoked influences like Kenny Clarke while adapting to free jazz's unpredictability.[35][6] Demonstrating remarkable versatility, Higgins navigated diverse tempos and genres, from hard bop swing to modal pulses, always prioritizing interactive dialogue with soloists through precise timing and tonal responses. In tracks like "Lonely Woman," he masterfully employed metric modulations, with drum patterns ranging from 299 to 337 beats per minute against horn phrasing at approximately 120 BPM, fostering a sense of collective momentum.[34][36][6] Higgins elevated polyrhythms and space as core compositional elements, drawing from African rhythmic roots to introduce surprising, risk-taking layers that influenced collective improvisation in free jazz. His strategic use of silence and sparse fills created magical interstices, allowing ensemble interplay to breathe and evolve organically.[6][35][34]Discography

As a Leader

Billy Higgins' work as a leader highlighted his compositional voice and rhythmic sensibilities, often in intimate small-group formats that blended his free jazz roots with melodic West Coast influences. Emerging later in his career after decades as a sought-after sideman, these recordings emphasized original material exploring themes of peace, introspection, and social consciousness, frequently incorporating spiritual jazz elements through expansive grooves and improvisational freedom.[37][2] His debut leader session, Soweto (1979, Red Records), captured a quartet with Bob Berg on tenor saxophone, Cedar Walton on piano, and Tony Dumas on bass, featuring originals like "Soweto" and "Clockwise" that evoked rhythmic urgency and global awareness amid post-bop structures.[37] This was followed by The Soldier (recorded 1979, released 1981, Timeless Records), another small-group effort with Monty Waters on alto saxophone, Cedar Walton on piano, and Walter Booker on bass, where Higgins contributed vocals on one track and originals such as "Sugar and Spice" and "Midnite Waltz," showcasing subtle swing and lyrical interplay.[37] In the 1980s, Higgins continued with Once More (1980, Red Records), reuniting with Berg, Walton, and Dumas for originals like "Plexis" and "Amazon," which highlighted fluid, conversational rhythms in a quintet setting.[37] Bridgework (recorded 1980 and 1986, released 1987, Contemporary Records) featured personnel from two sessions: the 1980 date with James Clay on tenor saxophone, Walton, and Dumas, and the 1986 session with Harold Land on tenor saxophone, Walton, and Buster Williams, focusing on interconnected improvisations through titles like the album's namesake track and "Decepticon."[37] The album Mr. Billy Higgins (recorded 1984, released 1985, Riza/Evidence) stood out as a drum-centric exploration, with Gary Bias on woodwinds, William Henderson on piano, and Dumas on bass performing originals such as "Dance of the Clones" and "Morning Awakening," blending spiritual introspection with West Coast lyricism.[37][38] Into the 1990s, Higgins' leadership embraced live energy and collaborations. The live Billy Higgins Quintet (recorded 1993 at Sweet Basil, released 1997, Evidence) brought together Oscar Brashear on trumpet, Land on tenor saxophone, Walton on piano, and David Williams on bass for originals like "Seeker" and "The Vision," capturing vibrant small-group dynamics at a New York club.[37] 3/4 for Peace (recorded 1993, released 1994, Red Records) featured Land on tenor and soprano saxophones, Henderson on piano, and Jeff Littleton on bass, with thematic pieces such as the title track and "In the Trenches" underscoring pacifist and communal sentiments in a spiritual jazz vein.[37][2] Higgins also participated as a key member in Cedar Walton's Eastern Rebellion ensembles, contributing to albums like Eastern Rebellion (1976, Prestige) and Beyond the Blue Horizon (1976, Prestige).[37] Later works include Ease On (1990, Timeless Records) with George Cables, David Williams, and Ralph Moore.[37] A posthumous release, Drumming Angel (2021, Elemental Music), features Higgins with Azar Lawrence from sessions in the 1990s.[39]| Year (Recording/Release) | Title | Label | Key Personnel | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Soweto | Red Records | Bob Berg (ts), Cedar Walton (p), Tony Dumas (b) | Originals emphasizing rhythmic and social themes.[37] |

| 1979/1981 | The Soldier | Timeless Records | Monty Waters (as), Cedar Walton (p), Walter Booker (b) | Small-group swing with Higgins originals.[37] |

| 1980 | Once More | Red Records | Bob Berg (ts), Cedar Walton (p), Tony Dumas (b) | Exploratory post-bop compositions.[37] |

| 1980 & 1986/1987 | Bridgework | Contemporary Records | 1980: James Clay (ts), Cedar Walton (p), Tony Dumas (b); 1986: Harold Land (ts), Cedar Walton (p), Buster Williams (b) | Interconnected improvisations from two sessions.[37] |

| 1984/1985 | Mr. Billy Higgins | Riza/Evidence | Gary Bias (woodwinds), William Henderson (p), Tony Dumas (b) | Drum-focused spiritual explorations.[37] |

| 1993/1997 | Billy Higgins Quintet (live) | Evidence | Oscar Brashear (tp), Harold Land (ts), Cedar Walton (p), David Williams (b) | Quintet originals in club setting.[37] |

| 1993/1994 | 3/4 for Peace | Red Records | Harold Land (ts/ss), William Henderson (p), Jeff Littleton (b) | Peace-themed spiritual jazz.[37] |

| 1976 | Eastern Rebellion | Prestige | Cedar Walton (p), Clifford Jordan (ts), Sam Jones (b) | Key member of Walton's group.[37] |

| 1976 | Beyond the Blue Horizon | Prestige | Cedar Walton (p), Clifford Jordan (ts), Sam Jones (b) | Continuation with Eastern Rebellion.[37] |

| 1990 | Ease On | Timeless Records | George Cables (p), David Williams (b), Ralph Moore (ts) | Mid-career quartet effort.[37] |

| 1990s/2021 | Drumming Angel | Elemental Music | Azar Lawrence (ts) | Posthumous release from earlier sessions.[39] |