Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Big band

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

| Big band | |

|---|---|

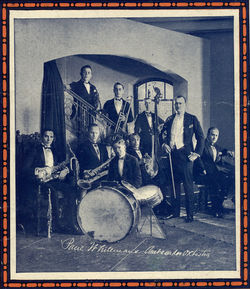

Paul Whiteman and his orchestra in 1921 | |

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | 1910s |

| Derivative forms | |

A big band or jazz orchestra is a type of musical ensemble of jazz music that usually consists of ten or more musicians with four sections: saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and a rhythm section. Big bands originated during the early 1910s and dominated jazz in the early 1940s when swing was most popular. The term "big band" is also used to describe a genre of music, although this was not the only style of music played by big bands.

Big bands started as accompaniment for dancing the Lindy Hop. In contrast to the typical jazz emphasis on improvisation, big bands relied on written compositions and arrangements. They gave a greater role to bandleaders, arrangers, and sections of instruments rather than soloists.

Instruments

[edit]

Big bands generally have four sections: trumpets, trombones, saxophones, and a rhythm section of guitar, piano, double bass, drums and sometimes vibraphone or other percussion.[1][2][3] The division in early big bands, from the 1920s to 1930s, was typically two or three trumpets, one or two trombones, three or four saxophones, and a rhythm section of four instruments.[4] In the 1940s, Stan Kenton's band used up to five trumpets, five trombones (three tenor and two bass trombones), five saxophones (two alto saxophones, two tenor saxophones, one baritone saxophone), and a rhythm section. Duke Ellington at one time used six trumpets.[5] While most big bands dropped the previously common jazz clarinet from their arrangements (other than the clarinet-led orchestras of Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman), many Duke Ellington songs had clarinet parts,[6] often replacing or doubling one of the tenor saxophone parts; more rarely, Ellington would substitute baritone sax for bass clarinet, such as in "Ase's Death" from Swinging Suites. Boyd Raeburn drew from symphony orchestras by adding flute, French horn, strings, and timpani to his band.[4] In the late 1930s, Shep Fields incorporated a solo accordion, temple blocks, piccolo, violins and a viola into his Rippling Rhythm Orchestra.[7][8] Paul Whiteman also featured a solo accordion in his ensemble.[9][10]

Jazz ensembles numbering eight (octet), nine (nonet) or ten (tentet) voices are sometimes called "little big bands".[11] During the 1940s, somewhat smaller configurations of the big band emerged in the form of the "rhythm sextet". These ensembles typically featured three or more accordions accompanied by piano, guitar, bass, cello, percussion, and marimba with vibes and were popularized by recording artists such as Charles Magnante,[12][13] Joe Biviano[14][15][16] and John Serry.[17][14][15][18][19][20][21]

Twenty-first century big bands can be considerably larger than their predecessors, exceeding 20 players, with some European bands using 29 instruments and some reaching 50.[22]

Seating and arrangements

[edit]In the most common seating for a 17-piece big band, each section is carefully set-up in a way to optimize the band's sound. For the wind players, there are 3 different types of parts: lead parts (including first trumpet, first trombone, and first alto sax), solo parts (including second or fourth trumpet, second trombone, and the first tenor sax), and section members (which include the rest of the band). The band is generally configured so lead parts are seated in the middle of their sections and solo parts are seated closest to the rhythm section. The fourth trombone part is generally played by a bass trombone. In some pieces the trumpets may double on flugelhorn or cornet, and saxophone players frequently double on other woodwinds such as flute, piccolo, clarinet, bass clarinet, or soprano saxophone.

It is useful to distinguish between the roles of composer, arranger and leader. The composer writes original music that will be performed by individuals or groups of various sizes, while the arranger adapts the work of composers in a creative way for a performance or recording.[23] Arrangers frequently notate all or most of the score of a given number, usually referred to as a "chart".[24] Bandleaders are typically performers who assemble musicians to form an ensemble of various sizes, select or create material for them, shape the music's dynamics, phrasing, and expression in rehearsals, and lead the group in performance often while playing alongside them.[25] One of the first prominent big band arrangers was Ferde Grofé, who was hired by Paul Whiteman to write for his “symphonic jazz orchestra”.[3] A number of bandleaders established long-term relationships with certain arrangers, such as the collaboration between leader Count Basie and arranger Neil Hefti.[26] Some bandleaders, such as Guy Lombardo, performed works composed by others (in Lombardo's case, often by his brother Carmen),[27] while others, such as Maria Schneider, take on all three roles.[28] In many cases, however, the distinction between these roles can become blurred.[29] Billy Strayhorn, for example, was a prolific composer and arranger, frequently collaborating with Duke Ellington, but rarely took on the role of bandleader, which was assumed by Ellington, who himself was a composer and arranger.[30]

Typical big band arrangements from the swing era were written in strophic form with the same phrase and chord structure repeated several times.[31] Each iteration, or chorus, commonly follows twelve bar blues form or thirty-two-bar (AABA) song form. The first chorus of an arrangement introduces the melody and is followed by choruses of development.[32] This development may take the form of improvised solos, written solo sections, and "shout choruses".[33]

An arrangement's first chorus is sometimes preceded by an introduction, which may be as short as a few measures or may extend to a chorus of its own. Many arrangements contain an interlude, often similar in content to the introduction, inserted between some or all choruses. Other methods of embellishing the form include modulations and cadential extensions.[34]

Some big ensembles, like King Oliver's, played music that was half-arranged, half-improvised, often relying on head arrangements.[35] A head arrangement is a piece of music that is formed by band members during rehearsal.[36] They experiment, often with one player coming up with a simple musical figure leading to development within the same section and then further expansion by other sections, with the entire band then memorizing the way they are going to perform the piece, without writing it on sheet music.[37] During the 1930s, Count Basie's band often used head arrangements, as Basie said, "we just sort of start it off and the others fall in."[38][39] Head arrangements were more common during the period of the 1930s because there was less turnover in personnel, giving the band members more time to rehearse.[40]: p.31

History

[edit]Dance music

[edit]Before 1910, social dance in America was dominated by steps such as the waltz and polka.[41] As jazz migrated from its New Orleans origin to Chicago and New York City, energetic, suggestive dances traveled with it. During the next decades, ballrooms filled with people doing the jitterbug and Lindy Hop. The dance duo Vernon and Irene Castle popularized the foxtrot while accompanied by the Europe Society Orchestra led by James Reese Europe.[1]

One of the first bands to accompany the new rhythms was led by a drummer, Art Hickman, in San Francisco in 1916. Hickman's arranger, Ferde Grofé, wrote arrangements in which he divided the jazz orchestra into sections that combined in various ways. This intermingling of sections became a defining characteristic of big bands. In 1919, Paul Whiteman hired Grofé to use similar techniques for his band. Whiteman was educated in classical music, and he called his new band's music symphonic jazz. The methods of dance bands marked a step away from New Orleans jazz. With the exception of Jelly Roll Morton, who continued playing in the New Orleans style, bandleaders paid attention to the demand for dance music and created their own big bands.[4] They incorporated elements of Broadway, Tin Pan Alley, ragtime, and vaudeville.[1]

Duke Ellington led his band at the Cotton Club in Harlem. Fletcher Henderson's career started when he was persuaded to audition for a job at Club Alabam in New York City, which eventually turned into a job as bandleader at the Roseland Ballroom. At these venues, which themselves gained notoriety, bandleaders and arrangers played a greater role than they had before. Hickman relied on Ferde Grofé, Whiteman on Bill Challis. Henderson and arranger Don Redman followed the template of King Oliver, but as the 1920s progressed they moved away from the New Orleans format and transformed jazz. They were assisted by a band full of talent: Coleman Hawkins on tenor saxophone, Louis Armstrong on cornet, and multi-instrumentalist Benny Carter, whose career lasted into the 1990s.[1]

The swing era

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

Swing music began appearing in the early 1930s and was distinguished by a more supple feel than the more literal 4

4 of early jazz. Walter Page is often credited with developing the walking bass,[42] although earlier examples exist, such as Wellman Braud on Ellington's Washington Wabble (1927).[citation needed]

This type of music flourished through the early 1930s, although there was little mass audience for it until around 1936. Up until that time, it was viewed with ridicule and sometimes looked upon as a menace.[43] After 1935, big bands rose to prominence playing swing music and held a major role in defining swing as a distinctive style. Western swing musicians also formed popular big bands during the same period.[citation needed]

A considerable range of styles evolved among the hundreds of popular bands. Many of the better known bands reflected the individuality of the bandleader, the lead arranger, and the personnel. Count Basie played a relaxed, propulsive swing, Bob Crosby (brother of Bing), more of a dixieland style,[44] Benny Goodman a hard driving swing, and Duke Ellington's compositions were varied and sophisticated. Many bands featured strong instrumentalists whose sounds dominated, such as the clarinets of Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw, the trombone of Jack Teagarden, the trumpet of Harry James, the drums of Gene Krupa, and the vibes of Lionel Hampton.[citation needed]

The popularity of many of the major bands was amplified by star vocalists, such as Frank Sinatra and Connie Haines with Tommy Dorsey, Helen O'Connell and Bob Eberly with Jimmy Dorsey, Ella Fitzgerald with Chick Webb, Billie Holiday and Jimmy Rushing with Count Basie, Kay Starr with Charlie Barnet, Bea Wain with Larry Clinton, Dick Haymes, Kitty Kallen and Helen Forrest with Harry James, Fran Warren with Claude Thornhill, Doris Day with Les Brown,[45] and Peggy Lee and Martha Tilton with Benny Goodman. Some bands were "society bands" which relied on strong ensembles,[46] such as the bands of Guy Lombardo and Paul Whiteman.[47]

A distinction is often made between so-called "hard bands", such as those of Count Basie and Tommy Dorsey, which emphasized quick hard-driving jump tunes, and "sweet bands", such as the Glenn Miller Orchestra and the Shep Fields Rippling Rhythm Orchestra[48][49] who specialized in less improvised tunes with more emphasis on sentimentality, featuring somewhat slower-paced, often heart-felt songs.[50]

By this time the big band was such a dominant force in jazz that the older generation found they either had to adapt to it or simply retire. With no market for small-group recordings (made worse by a Depression-era industry reluctant to take risks), musicians such as Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines led their own bands, while others, like Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver, lapsed into obscurity.[51] Even so, many of the most popular big bands of the swing era cultivated small groups within the larger ensemble: e.g. Benny Goodman developed both a trio and a quartet, Artie Shaw formed the Gramercy Five, Count Basie developed the Kansas City Six and Tommy Dorsey the Clambake Seven.[52]

The major "black" bands of the 1930s included, apart from Ellington's, Hines's, and Calloway's, those of Jimmie Lunceford, Chick Webb, and Count Basie. The "white" bands of Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey, Shep Fields and, later, Glenn Miller were more popular than their "black" counterparts from the middle of the decade. Bridging the gap to white audiences in the mid-1930s was the Casa Loma Orchestra and Benny Goodman's early band. The contrast in commercial popularity between "black" and "white" bands was striking: between 1935 and 1945 the top four "white" bands had 292 top ten records, of which 65 were number one hits, while the top four "black" bands had only 32 top ten hits, with only three reaching number one.[53]

White teenagers and young adults were the principal fans of the big bands in the late 1930s and early 1940s.[43] They danced to recordings and the radio and attended live concerts. They were knowledgeable and often biased toward their favorite bands and songs, and sometimes worshipful of famous soloists and vocalists. Many bands toured the country in grueling one-night stands. Traveling conditions and lodging were difficult, in part due to segregation in most parts of the United States, and the personnel often had to perform having had little sleep and food. Apart from the star soloists, many musicians received low wages and would abandon the tour if bookings disappeared. Sometimes bandstands were too small, public address systems inadequate, pianos out of tune. Bandleaders dealt with these obstacles through rigid discipline (Glenn Miller) and canny psychology (Duke Ellington).[citation needed]

Big bands raised morale during World War II.[54] Many musicians served in the military and toured with USO troupes at the front, with Glenn Miller losing his life while traveling between shows. Many bands suffered from loss of personnel during the war years, and, as a result, women replaced men who had been inducted, while all-female bands began to appear.[54] The 1942–44 musicians' strike worsened the situation. Vocalists began to strike out on their own. By the end of the war, swing was giving way to less danceable music, such as bebop. Many of the great swing bands broke up, as the times and tastes changed.[citation needed]

Many bands from the swing era continued for decades after the death or departure of their founders and namesakes, and some are still active in the 21st century, often referred to as "ghost bands", a term attributed to Woody Herman, referring to orchestras that persist in the absence of their original leaders.[55]

Modern big bands

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

Although big bands are identified with the swing era, they continued to exist after those decades, though the music they played was often different from swing. Bandleader Charlie Barnet's recording of "Cherokee" in 1942 and "The Moose" in 1943 have been called the beginning of the bop era. Woody Herman's first band, nicknamed the First Herd, borrowed from progressive jazz, while the Second Herd emphasized the saxophone section of three tenors and one baritone. In the 1950s, Stan Kenton referred to his band's music as "progressive jazz", "modern", and "new music".[56] He created his band as a vehicle for his compositions. Kenton pushed the boundaries of big bands by combining clashing elements and by hiring arrangers whose ideas about music conflicted. This expansive eclecticism characterized much of jazz after World War II. During the 1960s and '70s, Sun Ra and his Arketstra took big bands further out. Ra's eclectic music was played by a roster of musicians from ten to thirty and was presented as theater, with costumes, dancers, and special effects.[1]

As jazz was expanded during the 1950s through the 1970s, the Basie and Ellington bands were still around, as were bands led by Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa, Lionel Hampton, Earl Hines, Les Brown, Clark Terry, and Doc Severinsen. Progressive bands were led by Dizzy Gillespie, Gil Evans, Carla Bley, Toshiko Akiyoshi and Lew Tabackin, Don Ellis, and Anthony Braxton.[57]

In the 1960s and 1970s, big band rock became popular by integrating such musical ingredients as progressive rock experimentation, jazz fusion, and the horn choirs often used in blues and soul music, with some of the most prominent groups including Chicago; Blood, Sweat and Tears; Tower of Power; and, from Canada, Lighthouse. The genre was gradually absorbed into mainstream pop rock and the jazz rock sector.[58]

Other bandleaders used Brazilian and Afro-Cuban music with big band instrumentation, and big bands led by arranger Gil Evans, saxophonist John Coltrane (on the album Ascension from 1965) and bass guitarist Jaco Pastorius introduced cool jazz, free jazz and jazz fusion, respectively, to the big band domain. Modern big bands can be found playing all styles of jazz music. Some large contemporary European jazz ensembles play mostly avant-garde jazz using the instrumentation of the big bands. Examples include the Vienna Art Orchestra, founded in 1977, and the Italian Instabile Orchestra, active in the 1990s.

In the late 1990s, there was a swing revival in the U.S. The Lindy Hop became popular again and young people took an interest in big band styles again.

Big bands maintained a presence on American television, particularly through the late-night talk show, which has historically used big bands as house accompaniment. Typically the most prominent shows with the earliest time slots and largest audiences have bigger bands with horn sections while those in later time slots go with smaller, leaner ensembles.

Many college and university music departments offer jazz programs and feature big band courses in improvisation, composition, arranging, and studio recording, featuring performances by 18 to 20 piece big bands.[59]

Radio

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

During the 1930s, Earl Hines and his band broadcast from the Grand Terrace in Chicago every night across America.[60] In Kansas City and across the Southwest, an earthier, bluesier style was developed by such bandleaders as Bennie Moten and, later, by Jay McShann and Jesse Stone. By 1937, the "sweet jazz band" saxophonist Shep Fields was also featured over the airways on the NBC radio network in his Rippling Rhythm Revue, which also showcased a young Bob Hope as the announcer.[61][62][63]

Big band remotes on the major radio networks spread the music from ballrooms and clubs across the country during the 1930s and 1940s, with remote broadcasts from jazz clubs continuing into the 1950s on NBC's Monitor. Radio increased the fame of Benny Goodman, the "Pied Piper of Swing". Others challenged him, and battle of the bands became a regular feature of theater performances.

Similarly, Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians Orchestra also achieved widespread notoriety for nearly half a century as a result of their broadcasts on the NBC and CBS networks of the annual New Year's Eve celebrations from the Roosevelt Grill at New York's Roosevelt Hotel (1929-1959) and the Ballroom at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel (1959-1976) .[64]

Gloria Parker had a radio program on which she conducted the largest all-girl orchestra led by a female. She led her Swingphony while playing marimba. Phil Spitalny, a native of Ukraine, led a 22-piece female orchestra known as Phil Spitalny and His Hour of Charm Orchestra, named for his radio show, The Hour of Charm, during the 1930s and 1940s. Other female bands were led by trumpeter B. A. Rolfe, Anna Mae Winburn, and Ina Ray Hutton.[39]

Movies

[edit]Big Bands began to appear in movies in the 1930s through the 1960s, though cameos by bandleaders were often stiff and incidental to the plot. Shep Fields appeared with his Rippling Rhythm Orchestra in a playful and integrated animated performance of "This Little Ripple Had Rhythm" in the musical extravaganza The Big Broadcast of 1938.[65] Fictionalized biographical films of Glenn Miller, Gene Krupa, and Benny Goodman were made in the 1950s.

The bands led by Helen Lewis, Ben Bernie, and Roger Wolfe Kahn's band were filmed by Lee de Forest in his Phonofilm sound-on-film process in 1925, in three short films which are in the Library of Congress film collection.[66]

See also

[edit]- List of big bands

- Swing (jazz performance style), a term of praise for playing that has a strong rhythmic "groove" or drive

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Gioia, Ted (2011). The History of Jazz (2 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 100—. ISBN 978-0-19-539970-7.

- ^ "Big Band Music Genre Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ a b "How We Got the Big Sound of Big Band Jazz". Redlands Symphony. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c Collier, James (2002). Kernfeld, Barry (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). New York: Grove's Dictionaries. p. 122. ISBN 1-56159-284-6.

- ^ O'Meally, Robert G.; Edwards, Brent Hayes; Griffin, Farah Jasmine (2004). Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-50836-0. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, John S. (May 15, 1981). "Ellingtonians salute swing era clarinets". The New York Times. NYTco. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ "Shep Fields, Leader of Big Band Known for Rippling Rhythm". The New York Times. February 24, 1981. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ The Big Bands - 4th Edition George T. Simon. Schirmer Trade Books, London, 2012 ISBN 978-0-85712-812-6 "Shep Fields Biography" on Books.google.com

- ^ A Passion for Polka: Old-TIme Ethnic Music in America. Greene, Victor. University of California Press, 1992 p. 124 Paul Whiteman featured the accordion on Google Books.com

- ^ Music Around The World: A Global Encyclopedia . Andrew Martin & Matthew Mihalka editors. "Accordion (Americas) p. 3 Paul Whiteman Orchestra, accordion on Google Books

- ^ Palmer, Robert (April 5, 1981). "Two "Little Big Bands" offer new jazz". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ Music Around The World: A Global Encyclopedia. Andrew Martin & Matthew Mihalka editors. "Accordion (Americas) p. 3 Charles Magnanate & accordion on Google Books

- ^ Discography of American Historical Recordings: Charles Magnante's Accordion Quartette with guitar and string bass on uscb.edu

- ^ a b "Record Reviews". Billboard. April 27, 1946. p. 124. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ a b Joe Biviano, his Accordion and Rhythm Sextette; Tom Delaney; John Serry. "Leone Jump; Swing Low, Sweet Chariot; The Jazz Me Blues; Nursery Rhymes". Archive.org. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ The songs "Leone Jump" & "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" (Sonora 1110) from the album Accordion Capers (Sonora, MS-476) in 1946 by the Joe Biviano Orchestra with John Serry (second accordion & composer) archived at the Smithsonian Institute's National Museum of American History on americanhistory.si.edu

- ^ Discography of American Historical Recordings- John Serrapica (aka John Serry) as a member of the Charles Magnante Accordion Quartette with guitar and string bass on uscb.edu

- ^ "Dot into Pkgs". Billboard. September 8, 1956. pp. 22–. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Review of album Squeeze Play, p. 22 in The Billboard, 1 December 1956

- ^ Squeeze The: A Cultural History of the Accordion in America. Jacobson, Marion. University of Illinois Press, Chicago, Il. 2012, P. 39 "Advent of the Piano Accordion - Charles Magnante Accordion and Big Band jazz recordings on GoogleBooks.com

- ^ Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars and Stories that Shaped Our Culture. Edmondson, Jacqueline. ABC-CLIO, 2013, p. 3. "Accordion" - Charles Magnante, jazz bands, recordings on GoogleBooks.com

- ^ West, Michael J. "JazzTimes 10: Great Modern Big-Band Recordings". JazzTimes. Madavor Media. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "Difference Between Music Composer & Arranger". BestAccreditedColleges.org. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, William Forde (2014). Music in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Los Angeles: SAGE. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4522-8302-9. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ "What does a Bandleader do?". Berklee. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Hefti, Neal". ejazzlines.com. Hero Enterprises. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ Studwell, William Emmett and Mark Baldin (2000). The Big Band Reader Songs Favored by Swing Era Orchestras and Other Popular Ensembles. New York: Haworth Press. pp. 175–77. ISBN 978-0-7890-0914-2. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Chinen, Nate (July 24, 2020). "Composer Maria Schneider Returns, With A Reckoning, On 'Data Lords'". npr. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Abate, Robert (February 10, 2015). "Composer vs Arranger". Robert Abate Music. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Effinger, Shannon J. (July 27, 2021). "Billy Strayhorn's Lush Life Beyond Duke Ellington". uDiscoverMusic. Universal Music Group. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Big Band Music History". TheMusicHistory.com. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "A Guide To Song Forms – AABA Song Form". Songstuff. February 18, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Evan. "Big Band Arranging: for composers, orchestrators and arrangers: 16, Solos and Backgrounds". Evan Rogers: Orchestrator/Arranger/Conductor. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Dennis, Tyler. "Inside the Score in the 21st Century: Techniques for Contemporary Large Jazz Ensemble Composition". The Aquila Digital Community. University of Southern Mississippi. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Bowman, Robert (1982). The question of improvisation and head arrangement in King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band (M.F.A. thesis ed.). Toronto: York University. ISBN 978-0-612-15541-1.

- ^ "Definitions: Timbre, Ostinato, Stride". W.W. Norton. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ Simon, 105.

- ^ Kernfeld, Barry (1995). What to Listen to in Jazz. New Haven [u.a.]: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-300-05902-7.

- ^ a b John Behrens (March 2011). America's Music Makers: Big Bands & Ballrooms 1912–2011. AuthorHouse. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-1-4567-2952-3. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Martin, Henry and Keith Waters (2010). Jazz: The First 100 Years (3rd ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4390-8333-8. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "1910s Pop Trend: The Ragtime Dance Craze". Pop Song History. June 11, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ Schuller, Gunther (1991). The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930–1945. New York: Oxford University Press (print). p. 226.

- ^ a b Bindas, Kenneth J. (2001). Swing, that Modern Sound. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-57806-382-6. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy. "George Robert Crosby Bandleader, Vocalist, Actor, Radio/TV Host". JazzStandards.com. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "Les Brown". AllMusic. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Shaw, Arnold (1989). The Jazz Age: Popular Music in the 1920s. New York: Oxford University Press, Incorporated. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-19-506082-9.

- ^ Acosta, Leonardo (2016). Cubano Be, Cubano Bop: One Hundred Years of Jazz in Cuba. Daniel Whitesell, Paquito D'Rivera. Herndon: Smithsonian. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-58834-547-9.

- ^ Young, William H. (2005). "Music of the Great Depression". Shep Fields' Sweet Band on Google Books. p. 120.

- ^ Behrens, Jack (2006). "Big Bands and Great Ballrooms". Shep Fields' Sweet Band on Google Books. p. 23.

- ^ "Jazz Music: The Swing Era". University of Colorado Boulder. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ Dicaire, David (2010). Jazz Musicians of the Early Years, to 1945. Jefferson NC: McFarland. pp. 18, 35. ISBN 978-0-7864-8556-7. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Stewart, Alex (2007). Making the Scene: Contemporary New York City Big Band Jazz. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24953-0. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Starr, Larry; Waterman, Christopher Alan (2014). American Popular Music: From Minstrelsy to MP3. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-985911-5.

- ^ a b "B.C. music instructor says touring swing bands lifted military spirits during WW II". CBC News. November 11, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Epstein, Benjamin (July 18, 1986). "Sounds of Hot Jazz Stay Warm : Harry James Band to Play at the Mission". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Boyd, Michael. "Stan Kenton: Progressive Concepts in Jazz". plosin.com. Peter Losin. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ "Progressive Big Band". JAZZMUSICARCHIVES.COM (JMA). Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Hoffmann, Frank and Robert Birkline. "Big-band rock". Survey of American Popular Music. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Lawrence, Rick (November 6, 2019). "Best College Jazz Bands in The World". Studio Notes Online. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Travis, Dempsey J. (March 26, 1985). "Where The Jazz Was Super-hot". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: the Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-19-977078-6.

- ^ Strait, Raymond (2016). "Chapter 11. Bob Hope, Shep Fields and The Rippling Rhythm Revue". Bob Hope: A Tribute. Crossroad Press.

- ^ Photograph of Bob Hope as master of ceremonies on the "Rippling Rhythm Revue" Show in 1937 on Gettyimages

- ^ Crump, William D. (2008). Encyclopedia of New Year's Holidays Worldwide. London: McFarland & Co. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-7864-3393-3.

- ^ Stanley Green and Elaine Schmidt (2000). Hollywood musicals year by year. ISBN 0-634-00765-3.

Shep Fields and His Rippling Rhythm Orchestra in The Big Broadcaste of 1938

- ^ Geduld, Harry M. (1975). The Birth of the Talkies: From Edison to Jolson. Indiana University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-253-10743-5. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Page, Drew (1981). Drew’s Blues: A Sideman’s Life with the Big Bands. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-0686-0.

- Russo, William (1973). Composing for the Jazz Orchestra. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-73209-6. LCCN 61-8642.

- Simon, George T. (1967). The Big Bands. New York: The Macmillan Company. LCCN 67-26643. OCLC 1169701.

External links

[edit]- International Big Band Directory

- State University of New York, Fredonia. Rockefeller Arts Center. Jazz Big Band Arrangements

- Christopher Popa's Big Band Library

- Big Bands After The Big Band Era – Bill Kirchner, faculty at Manhattan School of Music.

- 6 Steps to Big Band Writing with Steven Feifke. – YouTube video.