Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

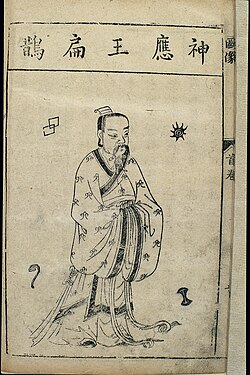

Bian Que

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Bian Que | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Stone carving from the Eastern Han dynasty, showing the divine healer Bian Que, depicted as a bird with a human head, treating sick people using acupuncture. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 扁鵲 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 扁鹊 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Bian Que (Chinese: 扁鵲; 407 – 310 BC) was an ancient Chinese figure traditionally said to be the earliest known Chinese physician during the Warring States period. His real name is said to be Qin Yueren (秦越人), but his medical skills were so amazing that people gave him the same name as the (original) legendary doctor Bian Que, from the time of the Yellow Emperor. He was a native of the State of Qi.[1]

Life and legend

[edit]According to the legend recorded in the Records of the Grand Historian (史记·扁鹊仓公列传), he was gifted with clairvoyance from a deity when he was working as an attendant at a hostel that catered to the nobility. It was there he encountered an old man who had stayed there for many years. Thankful for Bian Que's attentive service and politeness, the old man gave him a packet of medicine which he told Bian Que to boil in water. After taking this medicine, Bian Que gained the ability to see through the human body and thereby became an excellent diagnostician with X-ray-like ability.[2] He also excelled in pulse taking and acupuncture therapy.[3][4] He is ascribed the authorship of the Bian Que Neijing (Internal Classic of Bian Que). Han dynasty physicians claimed to have studied his works, which have since been lost. Tales state that he was a doctor of many disciplines, conforming to the local needs wherever he went. For example, in one city he was a children's doctor, and in another a female physician.

One famous legend tells of how once when Bian Que was in the State of Cai, he saw the lord of the state at the time and told him that he had a disease, which Bian Que claimed was only in his skin. The lord brushed this aside as at that time he felt no symptoms, and told his attendants that Bian Que was just trying to profit from the fears of others. Bian Que is said to have visited the lord many times thereafter, telling him each time how this sickness was becoming progressively worse, each time spreading into more of his body, from his skin to his blood and to his organs. The last time Bian Que went to see the lord, he looked in from afar, and rushed out of the palace. When an attendant of the lord asked him why he had done this, he replied that the disease was in the marrow and was incurable. The lord was said to have died soon after.

Another legend stated that once, while visiting the state of Guo, he saw people mourning on the streets. Upon inquiring what their grievances were, he got the reply that the heir apparent of the lord had died, and the lord was in mourning. Sensing something afoot, he is said to have gone to the palace to inquire about the circumstances of the death. After hearing of how the prince "died", he concluded that the prince had not really died, but was rather in a coma-like state. He set a single acupuncture needle in the Baihui point on the head, helping the prince to regain consciousness. Herbal medicine was boiled to help the prince sit up, and after Bian Que prescribed the prince with more herbal medicine, the prince healed fully within twenty days.

Bian Que advocated the four-step diagnoses of "Looking (at their tongues and their outside appearances), Listening (to their voice and breathing patterns), Inquiring (about their symptoms), and Taking (their pulse)."

The Daoist Liezi has a legend (tr. Giles 1912:81-83) that Bian Que used anesthesia to perform a double heart transplantation, with the xin (心), or heart, as the seat of consciousness. Gong Hu (公扈) from the state of Lu and Qi Ying (齊嬰) from the state of Zhao had opposite imbalances of qi (氣) "breath; life-force" and zhi (志) "will; intention". Gong had a qi ("mental power") deficiency while Qi had a zhi ("willpower") deficiency.

Bian Que suggests exchanging the hearts of the two to attain balance. Upon hearing his opinion, the patients agree to the procedure. Bian Que then gives the men an intoxicating wine that makes them "feign death" for three days. While they are under the anesthetic effects of this concoction, Bian Que "cut open their breasts, removed their hearts, exchanged and replaced them, and applied a numinous medicine, and when they awoke they were as good as new." Salguero (2009:203)

Some texts in bamboo slips unearthed in Chengdu may be composed by him.[5]

See also

[edit]- Hua Tuo, another famous doctor of ancient China

- List of Chinese physicians

Further reading

[edit]- 《史记·扁鹊仓公列传》

References

[edit]- ^ "Bian Qiao". Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Berkowitz, Alan (2005-01-01). Sima Qian, "Account Of The Legendary Physician Bian Que". pp. 174–178. doi:10.2307/j.ctvvn6qz.38.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Wang, Yuh-Ying Lin; Wang, Sheng-Hung; Jan, Ming-Yie; Wang, Wei-Kung (July 2012). "Past, Present, and Future of the Pulse Examination ( mài zhěn)". Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2 (3): 164–185. doi:10.1016/s2225-4110(16)30096-7. ISSN 2225-4110. PMC 3942893. PMID 24716130.

- ^ Ernst, Gernot (2017). "Hidden Signals-The History and Methods of Heart Rate Variability". Frontiers in Public Health. 5: 265. Bibcode:2017FrPH....5..265E. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00265. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 5649208. PMID 29085816.

- ^ 成都扁鹊学派医书遭质疑 专家:"敝昔"通假"扁鹊"--文化--人民网

Further reading

[edit]- Giles, Lionel. 1912. Taoist Teachings from the Book of Lieh-Tzŭ. Wisdom of the East.

- Salguero, C. Pierce. 2009. "The Buddhist medicine king in literary context: reconsidering an early medieval example of Indian influence on Chinese medicine and surgery", History of Religions 48.3:183-210.

- Woodford, P: Transplant Timeline. National Review of Medicine 2004 October 30; Volume 1 No. 20.

- Pien Ch'iao (Bian Que) at site of Institute for Traditional Medicine.

- "Divine Doctor--BianQue" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2003-07-19.