Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mohism

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2019) |

| Mojia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 墨家 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | School of Mo | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

Mohism or Moism (/ˈmoʊɪzəm/, Chinese: 墨家; pinyin: Mòjiā; lit. 'School of Mo') was an ancient Chinese philosophy of ethics and logic, rational thought, and scientific technology developed by the scholars who studied under the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 BC – c. 391 BC), embodied in an eponymous book: the Mozi. Among its major ethical tenets were altruism and a universal, unbiased respect and concern for all people, stressing the virtues of austerity and utilitarianism. Illuminating its original doctrine, later Mohist logicians were pivotal in the development of Chinese philosophy.

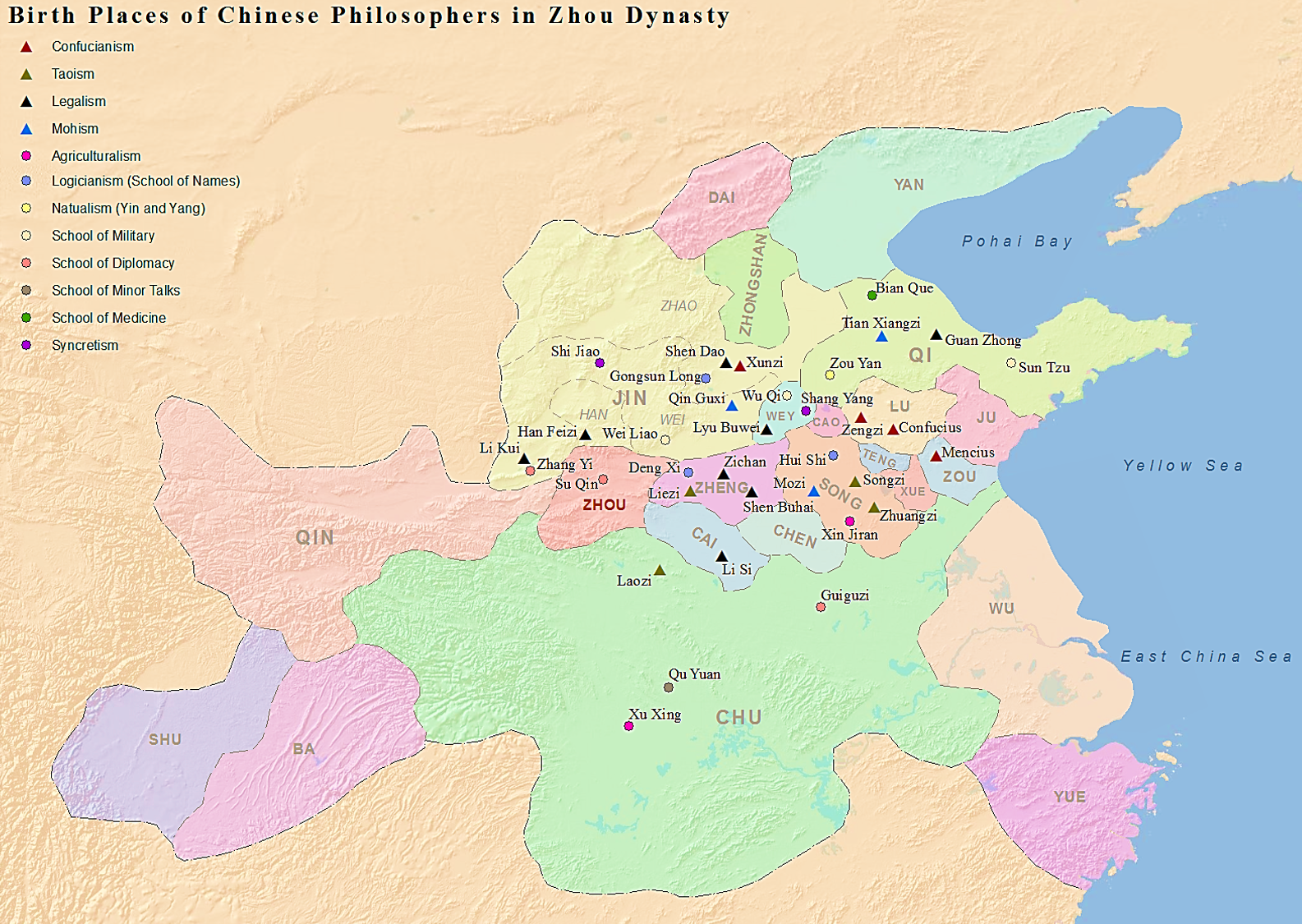

Mohism developed at about the same time as Confucianism, Taoism and Legalism, and was one of the four main philosophic schools from around 770–221 BC, during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period. During that time, Mohism was seen as a major rival to Confucianism. While its influence endured, Mohism almost disappeared as an independent school of thought as it transformed and integrated into sects of Taoism in the wake of the cultural transformations of the Qin dynasty, after 221 BC.

Paramilitaries

[edit]The Mohists formed a highly structured political organization that tried to realize the ideas they preached, the writings of Mozi. This political structure consisted of a network of local units in all the major kingdoms of China at the time, made up of elements from both the scholarly and working classes. Each unit was led by a juzi (literally, "chisel"—an image from craft making). Within the unit, a frugal and ascetic lifestyle was enforced. Each juzi would appoint his own successor. Like Confucians, they hired out their services not only for gain, but also in order to realize their own ethical ideals. They were often hired by the many warring kingdoms as advisers to the state. In this way, they were similar to the other wandering philosophers and knights-errant of the period.

Mohists believed in aiding the defensive warfare of smaller Chinese states against the hostile offensive warfare of larger domineering states. Mohists developed the sciences of fortification and statecraft, and wrote treatises on government, with topics ranging from efficient agricultural production to the laws of inheritance. One consequence of Mohist understanding of mathematics and the physical sciences, combined with their anti-militarist philosophy and skills as artisans, was that they became the pre-eminent siege-defense engineers prior to the Qin unification of China. Popular in early China, Mohist followers were employed for their ability as negotiators and as defense engineers.

Mozi and his disciples worked concertedly and systematically to invent and synthesise measures of benefit to defence, including defensive arms and strategy, and their corresponding logistics and military mobilisation. Many were actually applied, and remained an aspect of military affairs throughout history. The Mozi is hence highly respected by modern scholars, and ranks as a classic on military matters on a par with Sunzi's Art of War, the former of defensive strategy, the latter of offensive strategy.[1]

This component of Mohism is dramatized in the story of Gongshu,[2] recorded in the Mohist canon. Mozi travels 10 days and nights when he hears that Gongshu Pan has built machines for the king of Chu to use in an invasion of the smaller state of Song. Upon arriving in Chu, Mozi makes a wall out of his belt and sticks to represent machines, and shows Gongshu Pan that he can defend Song against any offensive strategy Chu might use. Mozi then announces that three hundred of his disciples are already on the walls of Song, ready to defend against Chu. The king cancels the invasion.

Overview

[edit]Mohism is best known for the concept popularly translated as "universal love" (Chinese: 兼愛; pinyin: jiān ài; lit. 'inclusive love/care'). According to Edward Craig, a more accurate translation for 兼愛 is "impartial care" because Mozi was more concerned with ethics than morality, as the latter tends to be based on fear more than hope.[3]

Caring and impartiality

[edit]Mohism promotes a philosophy of impartial caring; that is, a person should care equally for all other individuals, regardless of their actual relationship to them.[4] The expression of this indiscriminate caring is what makes a person a righteous being in Mohist thought. This advocacy of impartiality was a target of attack by other Chinese philosophical schools, most notably the Confucians, who believed that while love should be unconditional, it should not be indiscriminate. For example, children should hold a greater love for their parents than for random strangers.

Mozi is known for his insistence that all people are equally deserving of receiving material benefit and being protected from physical harm. In Mohism, morality is defined not by tradition and ritual, but rather by a constant moral guide that parallels utilitarianism. Tradition varies from culture to culture, and human beings need an extra-traditional guide to identify which traditions are morally acceptable. The moral guide must then promote and encourage social behaviours that maximize the general utility of all the people in that society.

The concept of Ai (愛) was developed by the Chinese philosopher Mozi in the 4th century BC in reaction to Confucianism's benevolent love. Mozi tried to replace what he considered to be the long-entrenched Chinese over-attachment to family and clan structures with the concept of "universal love" (jiān'ài, 兼愛). In this, he argued directly against Confucians who believed that it was natural and correct for people to care about different people in different degrees. Mozi, by contrast, believed people in principle should care for all people equally. Mohism stressed that rather than adopting different attitudes towards different people, love should be unconditional and offered to everyone without regard to reciprocation, not just to friends, family and other Confucian relations. Later in Chinese Buddhism, the term Ai (愛) was adopted to refer to a passionate caring love and was considered a fundamental desire. In Buddhism, Ai was seen as capable of being either selfish or selfless, the latter being a key element towards enlightenment.

Consequentialism

[edit]It is the business of the benevolent man to seek to promote what is beneficial to the world and to eliminate what is harmful, and to provide a model for the world. What benefits he will carry out; what does not benefit men he will leave alone.[5]

Unlike hedonistic utilitarianism, which views pleasure as a moral good, "the basic goods in Mohist consequentialist thinking are... order, material wealth, and increase in population".[6] During Mozi's era, war and famines were common, and population growth was seen as a moral necessity for a harmonious society. The "material wealth" of Mohist consequentialism refers to basic needs like shelter and clothing.[7] Stanford sinologist David Shepherd Nivison, in The Cambridge History of Ancient China, writes that the moral goods of Mohism "are interrelated: An example of this would be, more basic wealth, then more reproduction; more people, then more production and wealth... if people have plenty, they would be good, filial, kind, and so on unproblematically".[6] In contrast to Bentham's views, state consequentialism is not utilitarian because it is not hedonistic. The importance of outcomes that are good for the state outweigh the importance of individual pleasure and pain.

Society

[edit]Mozi posited that, when society functions as an organized organism, the wastes and inefficiencies found in the natural state (without organization) are reduced. He believed that conflicts are born from the absence of moral uniformity found in human cultures in the natural state, i.e. the absence of the definition of what is right (是 shì) and what is wrong (非 fēi). According to Mozi, we must therefore choose leaders who will surround themselves with righteous followers, who will then create the hierarchy that harmonizes Shi/Fei. In that sense, the government becomes an authoritative and automated tool. Assuming that the leaders in the social hierarchy are perfectly conformed to the ruler, who is perfectly submissive to Heaven, conformity in speech and behaviour is expected of all people. There is no freedom of speech [when defined as?] in this model. However, the potentially repressive element is countered by compulsory communication between the subjects and their leaders. Subjects are required to report all things good or bad to their rulers. Mohism is opposed to any form of aggression, especially war between states. It is, however, permissible for a state to use force in legitimate defense.

Meritocratic government

[edit]Mozi opposed nepotism, which was a social norm at the time. This practice allowed important government positions to be assigned based on familial ties rather than merit, restricting social mobility. Mozi taught that as long as a person was qualified for a task, he should keep his position, regardless of blood relations. If an officer was incapable, even if he was a close relative of the ruler, he ought to be demoted, even if it meant poverty.

A ruler should be in close proximity to talented people, treasuring talents and seeking their counsel frequently. Without discovering and understanding talents within the country, the country will be destroyed. History unfortunately saw many people who were murdered, not because of their frailties, but rather because of their strengths. A good bow is difficult to pull, but it shoots high. A good horse is difficult to ride, but it can carry weight and travel far. Talented people are difficult to manage, but they can bring respect to their rulers.

Law and order was an important aspect of Mozi's philosophy. He compared the carpenter, who uses standard tools to do his work, with the ruler, who might not have any standards by which to rule at all. The carpenter is always better off when depending on his standard tools, rather than on his emotions. Ironically, as his decisions affect the fate of an entire nation, it is even more important that a ruler maintains a set of standards, and yet he has none. These standards cannot originate from man, since no man is perfect; the only standards that a ruler uses have to originate from Heaven, since only Heaven is perfect. That law of Heaven is Love.

In a perfect governmental structure where the ruler loves all people benevolently, and officials are selected according to meritocracy, the people should have unity in belief and in speech. His original purpose in this teaching was to unite people and avoid sectarianism. However, in a situation of corruption and tyranny, this teaching might be misused as a tool for oppression.

Should the ruler be unrighteous, seven disasters would result for that nation. These seven disasters are:

- Neglect of the country's defense, yet there is much lavished on the palace.

- When pressured by foreigners, neighbouring countries are not willing to help.

- The people are engaged in unconstructive work while useless fools are rewarded.

- Law and regulations becomes too heavy such that there is repressive fear and people only look after their own good.

- The ruler lives in a mistaken illusion of his own ability and his country's strength.

- Trusted people are not loyal while loyal people are not trusted.

- Lack of food. Ministers are not able to carry out their work. Punishment fails to bring fear and reward fails to bring happiness.

A country facing these seven disasters will be destroyed easily by the enemy.

The measure of a country's wealth in Mohism is a matter of sufficient provision and a large population. Thriftiness is believed to be key to this end. With contentment with that which suffices, men will be free from excessive labour, long-term war and poverty from income gap disparity. This will enable birth rate to increase. Mozi also encourages early marriage.

Supernatural forces

[edit]Rulers of the period often ritually assigned punishments and rewards to their subjects in spiritually important places to garner the attention of these spirits and ensure that justice was done. The respect of these spirits was deemed so important that prehistoric Chinese ancestors had left their instructions on bamboo, plates and stones to ensure the continual obedience of their future descendants to the dictates of heaven. In Mozi's teachings, sacrifices of bulls and rams were mentioned during appointed times during the spring and autumn seasons. Spirits were described to be the preexisting primal spirits of nature, or the souls of humans who had died.

The Mohists polemicized against elaborate funeral ceremonies and other wasteful rituals, and called for austerity in life and in governance, but did not deem spiritual sacrifices wasteful. Using historical records, Mohists argued that the spirits of innocent men wrongfully murdered had appeared before to enact their vengeance. Spirits had also been recorded to have appeared to carry out other acts of justice. Mohists believed in heaven as a divine force (天 Tian), the celestial bureaucracy and spirits which knew about the immoral acts of man and punished them, encouraging moral righteousness, and were wary of some of the more atheistic thinkers of the time, such as Han Fei. Due to the vague nature of the records, there is a possibility that the Mohist scribes themselves may not have been clear about this subject.

Against fatalism

[edit]Mozi disagrees with the fatalistic mindset of people, accusing the mindset of bringing about poverty and suffering. To argue against this attitude, Mozi used three criteria (San Biao) to assess the correctness of views. These were:[8]

- Assessing them based on history

- Assessing them based on the experiences of common, average people

- Assessing their usefulness by applying them in law or politics[8]

In summary, fatalism, the belief that all outcomes are predestined or fated to occur, is an irresponsible belief espoused by those who refuse to acknowledge that their own lack of responsibility or the western view of sinfulness has caused the hardships of their lives. Prosperity or poverty are directly correlated with either virtue or vice,[9] respectively, so realised by deductive thinking and by one's own logic; not fate. Mozi calls fatalism that almost indefinitely ends in misanthroponic theory and behaviour, "A social heresy which needs to be disarmed, dissolved and destroyed".

Against ostentation

[edit]By the time of Mozi, Chinese rulers and the wealthier citizens already had the practice of extravagant burial rituals. Much wealth was buried with the dead, and ritualistic mourning could be as extreme as walking on a stick hunchback for three years in a posture of mourning. During such lengthy funerals, people are not able to attend to agriculture or care for their families, leading to poverty. Mozi spoke against such long and lavish funerals and also argued that this would even create resentment among the living.

Mozi views aesthetics as nearly useless. Unlike Confucius, he holds a distinctive repulsion to any development in ritual music and the fine arts. Mozi takes some whole chapters named "Against Music" (非樂) to discuss this. Though he mentions that he does enjoy and recognize what is pleasant, he sees them of no utilization in terms of governing, or of the benefit of common people. Instead, since development of music involves man's power, it reduces production of food; furthermore, appreciation of music results in less time for administrative works. This overdevelopment eventually results in shortage of food, as well as anarchy. This is because manpower will be diverted from agriculture and other fundamental works towards ostentations. Civilians will eventually imitate the ruler's lusts, making the situation worse. Mozi probably advocated this idea in response to the fact that during the Warring States period, the Zhou king and the aristocrats spent countless time in the development of delicate music while ordinary peasants could hardly meet their subsistence needs. To Mozi, bare necessities are sufficient; resources should be directed to benefit man.[citation needed]

School of Names

[edit]One of the offshoots of Mohism that has received some attention is the School of Names, who were interested in resolving logical puzzles. Not much survives from the writings of this school, since problems of logic were deemed trivial by most subsequent Chinese philosophers. Historians such as Joseph Needham have seen this group as developing a precursor philosophy of science that was never fully developed, but others[who?] believe that recognizing these Logicians as proto-scientists reveals too much of a modern bias.

Mathematics

[edit]The Mohist canon (Mo Jing) described various aspects of many fields associated with physical science, and provided a small wealth of information on mathematics as well. It provided an 'atomic' definition of the geometric point, stating that a line is separated into parts, and the part which has no remaining parts (i.e. cannot be divided into smaller parts) and thus the extreme end of a line is a point.[10] Much like Euclid's first and third definitions and Plato's 'beginning of a line', the Mo Jing stated that "a point may stand at the end (of a line) or at its beginning like a head-presentation in childbirth. (As to its invisibility) there is nothing similar to it."[11] Similar to the atomists of Democritus, the Mo Jing stated that a point is the smallest unit, and cannot be cut in half, since 'nothing' cannot be halved.[11] It stated that two lines of equal length will always finish at the same place,[11] while providing definitions for the comparison of lengths and for parallels,[12] along with principles of space and bounded space.[12] It also described the fact that planes without the quality of thickness cannot be piled up since they cannot mutually touch.[13] The book provided definitions for circumference, diameter, and radius, along with the definition of volume.[14]

Decline

[edit]With the unification of China under the Qin, China was no longer divided into various states constantly fighting each other: where previously the Mohists proved to be an asset when defending a city against an external threat, without wars, and in particular siege wars, there was no more need for their skills. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy suggests, in addition to the decline of siege warfare, "...the major factor is probably that as a social and philosophical movement, Mohism gradually collapsed into irrelevance. By the middle of the former Han dynasty, the more appealing aspects of Mohist thought were all shared with rival schools.

Their core ethical doctrines had largely been absorbed into Confucianism, though in a modified and unsystematic form. Key features of their political philosophy were probably shared with most other political thinkers, and their trademark opposition to warfare had been rendered effectively redundant by unification. The philosophy of language, epistemology, metaphysics, and science of the later Mohist Canons were recorded in difficult, dense texts that would have been nearly unintelligible to most readers (and that in any case quickly became corrupt). What remained as distinctively Mohist was a package of harsh, unappealing economic and cultural views, such as their obsession with parsimony and their rejection of music and ritual. Compared with the classical learning and rituals of the Confucians, the speculative metaphysics of Yin-Yang thinkers, and the romantic nature mysticism and literary sophistication of the Daoists, Mohism offered little to attract adherents, especially politically powerful ones."[15]

Modern perspectives

[edit]Jin Guantao, a professor of the Institute of Chinese Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Fan Hongye, a research fellow with the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Science Policy and Managerial Science, and Liu Qingfeng, a professor of the Institute of Chinese Culture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, have argued that without the influence of proto-scientific precepts in the ancient philosophy of Mohism, Chinese science lacked a definitive structure:[16]

From the middle and late Eastern Han to the early Wei and Jin dynasties, the net growth of ancient Chinese science and technology experienced a peak (second only to that of the Northern Song dynasty)... Han studies of the Confucian classics, which for a long time had hindered the socialization of science, were declining. If Mohism, rich in scientific thought, had rapidly grown and strengthened, the situation might have been very favorable to the development of a scientific structure. However, this did not happen because the seeds of the primitive structure of science were never formed. During the late Eastern Han, disastrous upheavals again occurred in the process of social transformation, leading to the greatest social disorder in Chinese history. One can imagine the effect of this calamity on science.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Insights into the Mozi and their Implications for the Study of Contemporary International Relations". The Chinese Journal of International Politics. Oxford Academic.

- ^ "Gong Shu" 公輸. Chinese Text Project.

- ^ The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward Craig. Routledge Publishing. 2005.

- ^ One Hundred Philosophers : A Guide to the World's Greatest Thinkers

- ^ Mo, Di; Xun, Kuang; Han, Fei (1967). Watson, Burton (ed.). Basic Writings of Mo Tzu, Hsün Tzu, and Han Fei Tzu. Columbia University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-231-02515-7.

- ^ a b Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (2011). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge University Press. p. 761. ISBN 978-0-52-147030-8.

- ^ Van Norden, Bryan W. (2011). Introduction to Classical Chinese Philosophy. Hackett Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-60-384468-0.

- ^ a b One hundred Philosophers. A guide to the world's greatest thinkers Peter J. King, Polish edition: Elipsa 2006

- ^ Loy, Hui-Chieh. "Mozi (Mo-tzu, c. 400s—300s B.C.E.)". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) (ISSN 2161-0002). Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Needham 1986, p. 92.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 93.

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 94.

- ^ Fraser, Chris (2015). "Mohism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ a b Jin, Fan, & Liu (1996), 178–179.

Sources

[edit]- Clarke, J (2000). Tao of the West: Western Transformation of Taoist Thought. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20620-4.

- Jin, Guantao; Fan, Hongye; Liu, Qingfeng (1996). Chinese Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- Ivanhoe, Philip J.; Van Norden, Brian W., eds. (2001). Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- ——— (2001). Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. New Haven, CT: Seven Bridges Press. ISBN 978-1-889119-09-0.

- Needham, Joseph (1956). History of Scientific Thought. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 2. p. 697. ISBN 978-0-52105800-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ——— (1986). Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 3. Taipei, Taiwan: Caves Books.

Further reading

[edit]- The Mozi: A Complete Translation. Translated by Johnston, Ian. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press. 2010.

- Brecht, Bertolt (1971). Me-ti. Buch der Wendungen (in German). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Chang, Wejen (1990). Traditional Chinese Jurisprudence: Legal Thought of Pre-Qin Thinkers. Cambridge.

- Chan, Wing-tsit, ed. (1969). A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01964-9.

- Frasier, Chris (2016). The Philosophy of the Mozi: The First Consequentialists. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231149273.

- Geaney, Jane (1999). "A Critique of A. C. Graham's Reconstruction of the 'Neo-Mohist Canons". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2307/605537. JSTOR 605537.

- Graham, Angus C. (1993). Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. Open Court. ISBN 0-8126-9087-7.

- ——— (2004) [1978]. Later Mohist Logic, Ethics and Science. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

- Hansen, Chad (1989). "Mozi: Language Utilitarianism: The Structure of Ethics in Classical China". The Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 16: 355–80. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.1989.tb00443.x.

- ——— (1992). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hsiao, Kung-chuan Hsiao (1979). A History of Chinese Political Thought. Vol. One: From the Beginnings to the Sixth Century A.D. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mei, Y. P. (1973) [1934]. Mo-tse, the Neglected Rival of Confucius. London: Arthur Probsthain. A general study of the man and his age, his works, and his teachings, with an extensive bibliography.

- Moritz, Ralf (1990). Die Philosophie im alten China (in German). Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-326-00466-4.

- Opitz, Peter J. (1999). Der Weg des Himmels: Zum Geist und zur Gestalt des politischen Denkens im klassischen China (in German). München: Fink. ISBN 3-7705-3380-1.

- Schmidt-Glintzer, Helwig, ed. (1992). Mo Ti: Von der Liebe des Himmels zu den Menschen (in German). München: Diederichs. ISBN 3-424-01029-4.

- ———, ed. (1975). Mo Ti: Solidarität und allgemeine Menschenliebe (in German). Düsseldorf/Köln: Diederichs. ISBN 3-424-00509-6.

- ———, ed. (1975). Mo Ti: Gegen den Krieg (in German). Düsseldorf/Köln: Diederichs. ISBN 3-424-00509-6.

- Sterckx, Roel (2019). Chinese Thought. From Confucius to Cook Ding. London: Penguin.

- Sun, Yirang (孙诒让), ed. (2001). Mozi xiangu 墨子闲诂 [Notes to zu Mozi]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

- Vitalii Aronovich, Rubin (1976). Individual and State in Ancient China: Essays on Four Chinese Philosophers. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04064-4.

- Yates, Robin D. S. (1980). "The Mohists on Warfare: Technology, Technique, and Justification". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 47 (3): 549–603.

External links

[edit] Media related to Mohism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mohism at Wikimedia Commons- Fraser, Chris. "Mohism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Fraser, Chris. "Mohist Canons". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Full text of the Mozi – Chinese Text Project

- Mohism at The Database of Religious History, University of British Columbia

Mohism

View on GrokipediaMohism was an ancient Chinese philosophical, social, and religious movement founded by the thinker Mozi, active from the late fifth to early fourth centuries BCE, that emphasized impartial concern for all people, utilitarianism, and opposition to offensive warfare and extravagant rituals.[1][2] The school's core doctrine of jian ai (impartial love or concern) sought to promote mutual benefit and social harmony by extending care equally to all, regardless of kinship or status, as a means to minimize conflict and maximize collective welfare in a era of incessant warfare.[1] Mohists critiqued Confucian emphasis on familial partiality and ritual propriety as conducive to inequality and waste, instead advocating meritocratic governance, frugality in personal and state affairs, and the standardization of measures and language to foster efficiency and unity.[2] They developed early forms of consequentialist ethics, where actions were judged by their outcomes in benefiting the populace, and contributed practical innovations in defensive engineering, such as city fortifications and siege weaponry, reflecting their role as itinerant technicians and advisors to states.[1] Mohism flourished during the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) as one of the "Hundred Schools of Thought," rivaling Confucianism in influence, with organized followers who lived communally and promoted their tenets through logical argumentation and empirical analogies.[1] The Mohist corpus, compiled in the Mozi text, includes treatises on ethics, politics, and later dialectical and scientific chapters that prefigure systematic logic, optics, and mechanics in Chinese thought.[1] Despite initial prominence, the school declined after the Qin unification in 221 BCE, possibly due to suppression under Legalism and assimilation into other traditions, though elements of Mohist universalism and pragmatism persisted in later Chinese intellectual history.[1]