Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Biography

View on Wikipedia

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or curriculum vitae (résumé), a biography presents a subject's life story, highlighting various aspects of their life, including intimate details of experience, and may include an analysis of the subject's personality.

Biographical works are usually non-fiction, but fiction can also be used to portray a person's life. One in-depth form of biographical coverage is called legacy writing. Works in diverse media, from literature to film, form the genre known as biography.

An authorized biography is written with the permission, cooperation, and at times, participation of a subject or a subject's heirs. An unauthorized biography is one written without such permission or participation. An autobiography is written by the person themselves, sometimes with the assistance of a collaborator or ghostwriter.

History

[edit]At first, biographical writings were regarded merely as a subsection of history with a focus on a particular individual of historical importance. The independent genre of biography as distinct from general history writing, began to emerge in the 18th century and reached its contemporary form at the turn of the 20th century.[1]

Historical biography

[edit]

Biography is the earliest literary genre in history. According to Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim, writing took its first steps toward literature in the context of the private tomb funerary inscriptions. These were commemorative biographical texts recounting the careers of deceased high royal officials.[2] The earliest biographical texts are from the 26th century BC.

In the 21st century BC, another famous biography was composed in Mesopotamia about Gilgamesh. One of the five versions could be historical.

From the same region a couple of centuries later, according to another famous biography, departed Abraham. He and his 3 descendants became subjects of ancient Hebrew biographies whether fictional or historical.

Xenophon (c. 430 – 355/354 BC) wrote the biography of Cyrus, the founder of the Persian Empire.

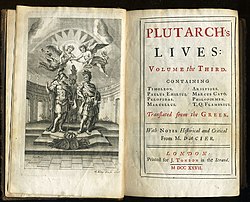

One of the earliest Roman biographers was Cornelius Nepos, who published his work Excellentium Imperatorum Vitae ("Lives of outstanding generals") in 44 BC. Longer and more extensive biographies were written in Greek by Plutarch, in his Parallel Lives, published about 80 A.D. In this work famous Greeks are paired with famous Romans, for example, the orators Demosthenes and Cicero, or the generals Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar; some fifty biographies from the work survive. Another well-known collection of ancient biographies is De vita Caesarum ("On the Lives of the Caesars") by Suetonius, written about AD 121 in the time of the emperor Hadrian. Meanwhile, in the eastern imperial periphery, Gospel described the life of Jesus.

In the early Middle Ages (AD 400 to 1450), there was a decline in awareness of the classical culture in Europe. During this time, the only repositories of knowledge and records of the early history in Europe were those of the Roman Catholic Church. Hermits, monks, and priests used this historic period to write biographies. Their subjects were usually restricted to the church fathers, martyrs, popes, and saints. Their works were meant to be inspirational to the people and vehicles for conversion to Christianity (see Hagiography). One significant secular example of a biography from this period is the life of Charlemagne by his courtier Einhard.

In Medieval Western India, there was a Sanskrit Jain literary genre of writing semi-historical biographical narratives about the lives of famous persons called Prabandhas. Prabandhas were written primarily by Jain scholars from the 13th century onwards and were written in colloquial Sanskrit (as opposed to Classical Sanskrit).[3] The earliest collection explicitly titled Prabandha- is Jinabhadra's Prabandhavali (1234 CE).

In Medieval Islamic Civilization (c. AD 750 to 1258), similar traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad and other important figures in the early history of Islam began to be written, beginning the Prophetic biography tradition. Early biographical dictionaries were published as compendia of famous Islamic personalities from the 9th century onwards. They contained more social data for a large segment of the population than other works of that period. The earliest biographical dictionaries initially focused on the lives of the prophets of Islam and their companions, with one of these early examples being The Book of The Major Classes by Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi. And then began the documentation of the lives of many other historical figures (from rulers to scholars) who lived in the medieval Islamic world.[4]

By the late Middle Ages, biographies became less church-oriented in Europe as biographies of kings, knights, and tyrants began to appear. The most famous of such biographies was Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory. The book was an account of the life of the fabled King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Following Malory, the new emphasis on humanism during the Renaissance promoted a focus on secular subjects, such as artists and poets, and encouraged writing in the vernacular.

Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists (1550) was the landmark biography focusing on secular lives. Vasari made celebrities of his subjects, as the Lives became an early "bestseller". Two other developments are noteworthy: the development of the printing press in the 15th century and the gradual increase in literacy.

Biographies in the English language began appearing during the reign of Henry VIII. John Foxe's Actes and Monuments (1563), better known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, was essentially the first dictionary of the biography in Europe, followed by Thomas Fuller's The History of the Worthies of England (1662), with a distinct focus on public life.

Influential in shaping popular conceptions of pirates, A General History of the Pyrates (1724), by Charles Johnson, is the prime source for the biographies of many well-known pirates.[5]

A notable early collection of biographies of eminent men and women in the United Kingdom was Biographia Britannica (1747–1766) edited by William Oldys.

The American biography followed the English model, incorporating Thomas Carlyle's view that biography was a part of history. Carlyle asserted that the lives of great human beings were essential to understanding society and its institutions. While the historical impulse would remain a strong element in early American biography, American writers carved out a distinct approach. What emerged was a rather didactic form of biography, which sought to shape the individual character of a reader in the process of defining national character.[6][7]

Emergence of the genre

[edit]

The first modern biography, and a work that exerted considerable influence on the evolution of the genre, was James Boswell's The Life of Samuel Johnson, a biography of lexicographer and man-of-letters Samuel Johnson published in 1791.[8][unreliable source?][9][10]

While Boswell's personal acquaintance with his subject only began in 1763, when Johnson was 54 years old, Boswell covered the entirety of Johnson's life by means of additional research. Itself an important stage in the development of the modern genre of biography, it has been claimed to be the greatest biography written in the English language. Boswell's work was unique in its level of research, which involved archival study, eye-witness accounts and interviews, its robust and attractive narrative, and its honest depiction of all aspects of Johnson's life and character – a formula which serves as the basis of biographical literature to this day.[11]

Biographical writing generally stagnated during the 19th century – in many cases there was a reversal to the more familiar hagiographical method of eulogizing the dead, similar to the biographies of saints produced in Medieval times. A distinction between mass biography and literary biography began to form by the middle of the century, reflecting a breach between high culture and middle-class culture. However, the number of biographies in print experienced a rapid growth, thanks to an expanding reading public. This revolution in publishing made books available to a larger audience of readers. In addition, affordable paperback editions of popular biographies were published for the first time. Periodicals began publishing a sequence of biographical sketches.[12]

Autobiographies became more popular, as with the rise of education and cheap printing, modern concepts of fame and celebrity began to develop. Autobiographies were written by authors, such as Charles Dickens (who incorporated autobiographical elements in his novels) and Anthony Trollope (his Autobiography appeared posthumously, quickly becoming a bestseller in London[13]), philosophers, such as John Stuart Mill, churchmen – John Henry Newman – and entertainers – P. T. Barnum.

Modern biography

[edit]The sciences of psychology and sociology were ascendant at the turn of the 20th century and would heavily influence the new century's biographies.[14] The demise of the "great man" theory of history was indicative of the emerging mindset. Human behavior would be explained through Darwinian theories. "Sociological" biographies conceived of their subjects' actions as the result of the environment, and tended to downplay individuality. The development of psychoanalysis led to a more penetrating and comprehensive understanding of the biographical subject, and induced biographers to give more emphasis to childhood and adolescence. Clearly these psychological ideas were changing the way biographies were written, as a culture of autobiography developed, in which the telling of one's own story became a form of therapy.[12] The conventional concept of heroes and narratives of success disappeared in the obsession with psychological explorations of personality.

British critic Lytton Strachey revolutionized the art of biographical writing with his 1918 work Eminent Victorians, consisting of biographies of four leading figures from the Victorian era: Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold, and General Gordon.[15] Strachey set out to breathe life into the Victorian era for future generations to read. Up until this point, as Strachey remarked in the preface, Victorian biographies had been "as familiar as the cortège of the undertaker", and wore the same air of "slow, funereal barbarism." Strachey defied the tradition of "two fat volumes ... of undigested masses of material" and took aim at the four iconic figures. His narrative demolished the myths that had built up around these cherished national heroes, whom he regarded as no better than a "set of mouth bungled hypocrites". The book achieved worldwide fame due to its irreverent and witty style, its concise and factually accurate nature, and its artistic prose.[16]

In the 1920s and 1930s, biographical writers sought to capitalize on Strachey's popularity by imitating his style. This new school featured iconoclasts, scientific analysts, and fictional biographers and included Gamaliel Bradford, André Maurois, and Emil Ludwig, among others. Robert Graves (I, Claudius, 1934) stood out among those following Strachey's model of "debunking biographies." The trend in literary biography was accompanied in popular biography by a sort of "celebrity voyeurism", in the early decades of the century. This latter form's appeal to readers was based on curiosity more than morality or patriotism. By World War I, cheap hard-cover reprints had become popular. The decades of the 1920s witnessed a biographical "boom."

American professional historiography gives a limited role to biography, preferring instead to emphasize deeper social and cultural influences. Political biographers historically incorporated moralizing judgments into their work, with scholarly biography being an uncommon genre before the mid-1920s. Allan Nevins was a major contributor in the 1930s to the multivolume Dictionary of American Biography. Nevins also sponsored a series of long political biographies. Later biographers sought to show how political figures balanced power and responsibility. However, many biographers found that their subjects were not as morally pure as they originally thought, and young historians after 1960 tended to be more critical. The exception is Robert Remini whose books on Andrew Jackson idolize its hero and fends off criticisms. The study of decision-making in politics is important for scholarly political biographers, who can take different approaches such as focusing on psychology/personality, bureaucracy/interests, fundamental ideas, or societal forces. However, most documentation favors the first approach, which emphasizes personalities. Biographers often neglect the voting blocs and legislative positions of politicians and the organizational structures of bureaucracies. A more promising approach is to locate a person's ideas through intellectual history, but this has become more difficult with the philosophical shallowness of political figures in recent times. Political biography can be frustrating and challenging to integrate with other fields of political history.[17]

The feminist scholar Carolyn Heilbrun observed that women's biographies and autobiographies began to change character during the second wave of feminist activism. She cited Nancy Milford's 1970 biography Zelda, as the "beginning of a new period of women's biography, because "[only] in 1970 were we ready to read not that Zelda had destroyed Fitzgerald, but Fitzgerald her: he had usurped her narrative." Heilbrun named 1973 as the turning point in women's autobiography, with the publication of May Sarton's Journal of a Solitude, for that was the first instance where a woman told her life story, not as finding "beauty even in pain" and transforming "rage into spiritual acceptance," but acknowledging what had previously been forbidden to women: their pain, their rage, and their "open admission of the desire for power and control over one's life."[18]

Recent years

[edit]In recent years,[when?] multimedia biography has become more popular than traditional literary forms. Along with documentary biographical films, Hollywood produced numerous commercial films based on the lives of famous people. The popularity of these forms of biography have led to the proliferation of TV channels dedicated to biography, including A&E, The Biography Channel, and The History Channel.

CD-ROM and online biographies have also appeared. Unlike books and films, they often do not tell a chronological narrative: instead they are archives of many discrete media elements related to an individual person, including video clips, photographs, and text articles. Biography-Portraits were created in 2001, by the German artist Ralph Ueltzhoeffer. Media scholar Lev Manovich says that such archives exemplify the database form, allowing users to navigate the materials in many ways.[19] General "life writing" techniques are a subject of scholarly study.[20]

In recent years, debates have arisen as to whether all biographies are fiction, especially when authors are writing about figures from the past. President of Wolfson College at Oxford University, Hermione Lee argues that all history is seen through a perspective that is the product of one's contemporary society and as a result, biographical truths are constantly shifting. So, the history biographers write about will not be the way that it happened; it will be the way they remembered it.[21] Debates have also arisen concerning the importance of space in life-writing.[22]

Daniel R. Meister in 2017 argued that:

- Biography Studies is emerging as an independent discipline, especially in the Netherlands. This Dutch School of biography is moving biography studies away from the less scholarly life writing tradition and towards history by encouraging its practitioners to utilize an approach adapted from microhistory.[23]

Biographical research

[edit]Biographical research is defined by Miller as a research method that collects and analyses a person's whole life, or portion of a life, through the in-depth and unstructured interview, or sometimes reinforced by semi-structured interview or personal documents.[24] It is a way of viewing social life in procedural terms, rather than static terms. The information can come from "oral history, personal narrative, biography and autobiography" or "diaries, letters, memoranda and other materials".[25] The central aim of biographical research is to produce rich descriptions of persons or "conceptualise structural types of actions", which means to "understand the action logics or how persons and structures are interlinked".[26] This method can be used to understand an individual's life within its social context or understand the cultural phenomena.

Critical issues

[edit]There are many largely unacknowledged pitfalls to writing good biographies, and these largely concern the relation between firstly the individual and the context, and, secondly, the private and public. Paul James writes:

The problems with such conventional biographies are manifold. Biographies usually treat the public as a reflection of the private, with the private realm being assumed to be foundational. This is strange given that biographies are most often written about public people who project a persona. That is, for such subjects the dominant passages of the presentation of themselves in everyday life are already formed by what might be called a 'self-biofication' process.[27]

Book awards

[edit]Several countries offer an annual prize for writing a biography such as the:

- Drainie-Taylor Biography Prize – Canada

- National Biography Award – Australia

- Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography – United States

- Whitbread Prize for Best Biography – United Kingdom

- J. R. Ackerley Prize for Autobiography – United Kingdom

- Prix Goncourt de la Biographie – France

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Kendall.

- ^ Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006, vol I, p 3.

- ^ Thaker, Jayant Premshankar (1970). Laghuprabandhasaṅgrahah. Oriental Institute. p. 18.

- ^ Nawas 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Johnson 2002, p. ?.

- ^ Casper 1999, p. ?.

- ^ Stone 1982, p. ?.

- ^ Butler 2012.

- ^ Ingram et al. 1998, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Turnbull 2019.

- ^ Brocklehurst, Steven (16 May 2013). "James Boswell: The Man who Re-Invented Biography". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ a b Casper 1999.

- ^ Roberts 1883, p. 13.

- ^ Stone 1982.

- ^ Levy, Paul (20 July 2002). "A String Quartet in Four Movements". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Jones 2009.

- ^ Jack P Green, ed. Encyclopedia of American political history (Scribner's, 1984) 1:2-4.

- ^ Heilbrun 1988, pp. 12, 13.

- ^ Manovich 2001, p. 220.

- ^ Hughes 2009, p. 159.

- ^ Derham 2014.

- ^ Regard 2003.

- ^ Meister 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Roberts 2002.

- ^ Zinn 2004, p. 3.

- ^ James 2013, p. 124.

References

[edit]- Butler, Paul (19 April 2012). "James Boswell's 'Life of Johnson': The First Modern Biography". University of Mary Washington Libraries. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Casper, Scott E. (1999). Constructing American Lives: Biography and Culture in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4765-7.

- Derham, Katie (2014) [First published in 2014]. The Art of Life: Are Biographies Fiction? (MP4) (Video). Stephen Frears, Hermione Lee, Ray Monk. Institute of Arts and Ideas. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Heilbrun, Carolyn G. (1988). Writing a Woman's Life. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02601-6.

- Hughes, Kathryn (2009). "Review of Teaching Life Writing Texts, ed. Miriam Fuchs and Craig Howes" (PDF). Journal of Historical Biography. 5: 159–163. ISSN 1911-8538. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Johnson, Charles (2002). A General History of the Robberies & Murders of the most Notorious Pirates. London: Conway Maritime. ISBN 0-85177-919-0.

- Ingram, Allan; Rawson, Claude; Waingrow, Marshall; Boswell, James (1998). "James Boswell's 'Life of Johnson': An Edition of the Original Manuscript, in Four Volumes. Vol. 1. 1709-1765". The Yearbook of English Studies. 28: 319–320. doi:10.2307/3508791. JSTOR 3508791.

- James, Paul (2013). "Closing Reflections: Confronting Contradictions in Biographies of Nations and Peoples". Humanities Research. 19 (1): 124.

- Jones, Malcolm (28 October 2009). "Boswell, Johnson, & the Birth of Modern Biography". Newsweek. New York. ISSN 0028-9604. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Kendall, Paul Murray. "Biography". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Lee, Hermione (2009). Biography: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953354-1.

- Manovich, Lev (2001). The Language of New Media. Leonardo Book Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-63255-3.

- Meister, Daniel R. (2018). "The biographical turn and the case for historical biography". History Compass. 16 (1) e12436: 2. doi:10.1111/hic3.12436. ISSN 1478-0542.

- Miller, Robert L. (2003). "Biographical Method". In Miller, Robert L.; Brewer, John D. (eds.). The A–Z of Social Research: A Dictionary of Key Social Science Research Concepts. London: Sage Publications. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-7619-7133-7.

- Nawas, John A. (2006). "Biography and Biographical Works". In Meri, Josef W. (ed.). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge. pp. 110–112. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.

- Regard, Frédéric, ed. (2003). Mapping the Self: Space, Identity, Discourse in British Auto/Biography. Saint-Étienne, France: Publications de l'Université de Saint-Étienne. ISBN 978-2-86272269-6.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1918). "Biography". Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 3. pp. 718–719.

- Roberts, Brian (2002). Biographical Research. Understanding Social Research. Buckingham, England: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-20287-4.

- Roberts, Charles George Douglas, ed. (6 December 1883). "Literary Gossip". The Week. Vol. 1, no. 1. p. 13.

- Stone, Albert E. (1982). Autobiographical Occasions and Original Acts: Versions of American Identity from Henry Adams to Nate Shaw. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-7845-3.

- Turnbull, Gordon (2019-10-10). "Boswell, James (1740–1795), lawyer, diarist, and biographer of Samuel Johnson". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2950. Retrieved 2020-05-14. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- Zinn, Jens O. (2004). Introduction to Biographical Research (Working paper 2004/4). Canterbury, England: Social Contexts and Responses to Risk Network, University of Kent.

Further reading

[edit]- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 952–954.

- Sidney Lee (1911), Principles of Biography, London: Cambridge University Press, Wikidata Q107333538

- Solomon, Maynard (2001). "Biography". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.41156. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription, Wikilibrary access, or UK public library membership required)

External links

[edit]- "Biography", In Our Time, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Richard Holmes, Nigel Hamilton and Amanda Foreman (June 22, 2000).