Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bond (finance)

View on Wikipedia| Securities |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Numismatics the study of currency |

|---|

|

In finance, a bond is a type of security under which the issuer (debtor) owes the holder (creditor) a debt, and is obliged – depending on the terms – to provide cash flow to the creditor; which usually consists of repaying the principal (the amount borrowed) of the bond at the maturity date, as well as interest (called the coupon) over a specified amount of time.[1] The timing and the amount of cash flow provided varies, depending on the economic value that is emphasized upon, thus giving rise to different types of bonds.[1] The interest is usually payable at fixed intervals: semiannual, annual, and less often at other periods. Thus, a bond is a form of loan or IOU. Bonds provide the borrower with external funds to finance long-term investments or, in the case of government bonds, to finance current expenditure.

Bonds and stocks are both securities, but the major difference between the two is that (capital) stockholders have an equity stake in a company (i.e. they are owners), whereas bondholders have a creditor stake in a company (i.e. they are lenders). As creditors, bondholders have priority over stockholders. This means they will be repaid in advance of stockholders, but will rank behind secured creditors, in the event of bankruptcy. Another difference is that bonds usually have a defined term, or maturity, after which the bond is redeemed, whereas stocks typically remain outstanding indefinitely. An exception is an irredeemable bond, which is a perpetuity, that is, a bond with no maturity. Certificates of deposit (CDs) or short-term commercial paper are classified as money market instruments and not bonds: the main difference is the length of the term of the instrument.

The most common forms include municipal, corporate, and government bonds. Very often the bond is negotiable, that is, the ownership of the instrument can be transferred in the secondary market. This means that once the transfer agents at the bank medallion-stamp the bond, it is highly liquid on the secondary market.[2] The price of a bond in the secondary market may differ substantially from the principal due to various factors in bond valuation.

Bonds are often identified by their international securities identification number, or ISIN, which is a 12-digit alphanumeric code that uniquely identifies debt securities.

Etymology

[edit]In English, the word "bond" relates to the etymology of "bind". The use of the word "bond" in this sense of an "instrument binding one to pay a sum to another" dates from at least the 1590s.[3][4]

Issuance

[edit]Bonds are issued by public authorities, credit institutions, companies and supranational institutions in the primary markets. The most common process for issuing bonds is through underwriting. When a bond issue is underwritten, one or more securities firms or banks, forming a syndicate, buy the entire issue of bonds from the issuer and resell them to investors. The security firm takes the risk of being unable to sell on the issue to end investors. Primary issuance is arranged by bookrunners who arrange the bond issue, have direct contact with investors and act as advisers to the bond issuer in terms of timing and price of the bond issue. The bookrunner is listed first among all underwriters participating in the issuance in the tombstone ads commonly used to announce bonds to the public. The bookrunners' willingness to underwrite must be discussed prior to any decision on the terms of the bond issue as there may be limited demand for the bonds.

In contrast, government bonds are usually issued in an auction. In some cases, both members of the public and banks may bid for bonds. In other cases, only market makers may bid for bonds. The overall rate of return on the bond depends on both the terms of the bond and the price paid.[5] The terms of the bond, such as the coupon, are fixed in advance and the price is determined by the market.

In the case of an underwritten bond, the underwriters will charge a fee for underwriting. An alternative process for bond issuance, which is commonly used for smaller issues and avoids this cost, is the private placement bond. Bonds sold directly to buyers may not be tradeable in the bond market.[6]

Historically, an alternative practice of issuance was for the borrowing government authority to issue bonds over a period of time, usually at a fixed price, with volumes sold on a particular day dependent on market conditions. This was called a tap issue or bond tap.

Features

[edit]Principal

[edit]

Nominal, principal, par, or face amount is the amount on which the issuer pays interest, and which, most commonly, has to be repaid at the end of the term. Some structured bonds can have a redemption amount which is different from the face amount and can be linked to the performance of particular assets.

Maturity

[edit]The issuer is obligated to repay the nominal amount on the maturity date. As long as all due payments have been made, the issuer has no further obligations to the bond holders after the maturity date. The length of time until the maturity date is often referred to as the term or tenor or maturity of a bond. The maturity can be any length of time, although debt securities with a term of less than one year are generally designated money market instruments rather than bonds. Most bonds have a term shorter than 30 years. Some bonds have been issued with terms of 50 years or more, and historically there have been some issues with no maturity date (irredeemable). In the market for United States Treasury securities, there are four categories of bond maturities:

- short term (bills): maturities under one year;

- medium term (notes): maturities between one and ten years;

- long term (bonds): maturities between ten and thirty years;

- perpetual: no maturity period.

Coupon

[edit]

The coupon is the interest rate that the issuer pays to the holder. For fixed rate bonds, the coupon is fixed throughout the life of the bond. For floating rate notes, the coupon varies throughout the life of the bond and is based on the movement of a money market reference rate (historically this was generally LIBOR, but with its discontinuation the market reference rate has transitioned to SOFR).

Historically, coupons were physical attachments to the paper bond certificates, with each coupon representing an interest payment. On the interest due date, the bondholder would hand in the coupon to a bank in exchange for the interest payment. Today, interest payments are almost always paid electronically. Interest can be paid at different frequencies: generally semi-annual (every six months) or annual.

Yield

[edit]The yield is the rate of return received from investing in the bond. It usually refers to one of the following:

- The current yield, or running yield: the annual interest payment divided by the current market price of the bond (often the clean price).

- The yield to maturity (or redemption yield, as it is termed in the United Kingdom) is an estimate of the total rate of return anticipated to be earned by an investor who buys a bond at a given market price, holds it to maturity, and receives all interest payments and the capital redemption on schedule.[7] It is a more useful measure of the return on a bond than current yield because it takes into account the present value of future interest payments and principal repaid at maturity. The yield to maturity or redemption yield calculated at the time of purchase is not necessarily the return the investor will actually earn, as finance scholars Dr. Annette Thau and Dr. Frank Fabozzi have noted. The yield to maturity will be realized only under certain conditions, including 1) all interest payments are reinvested rather than spent, and 2) all interest payments are reinvested at the yield to maturity calculated at the time the bond is purchased.[8][9] This distinction may not be a concern to bond buyers who intend to spend rather than reinvest the coupon payments, such as those practicing asset/liability matching strategies.

Credit quality

[edit]The quality of the issue refers to the probability that the bondholders will receive the amounts promised at the due dates. In other words, credit quality tells investors how likely the borrower is going to default. This will depend on a wide range of factors. High-yield bonds are bonds that are rated below investment grade by the credit rating agencies. As these bonds are riskier than investment grade bonds, investors expect to earn a higher yield. These bonds are also called junk bonds.

Market price

[edit]The market price of a tradable bond will be influenced, among other factors, by the amounts, currency and timing of the interest payments and capital repayment due, the quality of the bond, and the available redemption yield of other comparable bonds which can be traded in the markets.

The price can be quoted as clean or dirty. "Dirty" includes the present value of all future cash flows, including accrued interest, and is most often used in Europe. "Clean" does not include accrued interest, and is most often used in the U.S.

The issue price at which investors buy the bonds when they are first issued will typically be approximately equal to the nominal amount. The net proceeds that the issuer receives are thus the issue price, less issuance fees. The market price of the bond will vary over its life: it may trade at a premium (above par, usually because market interest rates have fallen since issue), or at a discount (price below par, if market rates have risen or there is a high probability of default on the bond).

Others

[edit]- Indentures and Covenants—An indenture is a formal debt agreement that establishes the terms of a bond issue, while covenants are the clauses of such an agreement. Covenants specify the rights of bondholders and the duties of issuers, such as actions that the issuer is obligated to perform or is prohibited from performing. In the U.S., federal and state securities and commercial laws apply to the enforcement of these agreements, which are construed by courts as contracts between issuers and bondholders. The terms may be changed only with great difficulty while the bonds are outstanding, with amendments to the governing document generally requiring approval by a majority (or super-majority) vote of the bondholders.

- Optionality: Occasionally a bond may contain an embedded option; that is, it grants option-like features to the holder or the issuer:

- Callability—Some bonds give the issuer the right to repay the bond before the maturity date on the call dates; see call option. These bonds are referred to as callable bonds. Most callable bonds allow the issuer to repay the bond at par. With some bonds, the issuer has to pay a premium, the so-called call premium. This is mainly the case for high-yield bonds. These have very strict covenants, restricting the issuer in its operations. To be free from these covenants, the issuer can repay the bonds early, but only at a high cost.

- Puttability—Some bonds give the holder the right to force the issuer to repay the bond before the maturity date on the put dates; see put option. These are referred to as retractable or putable bonds.

- Call dates and put dates—the dates on which callable and putable bonds can be redeemed early. There are four main categories:

- A Bermudan callable has several call dates, usually coinciding with coupon dates.

- A European callable has only one call date. This is a special case of a Bermudan callable.

- An American callable can be called at any time until the maturity date.

- A death put is an optional redemption feature on a debt instrument allowing the beneficiary of the estate of a deceased bondholder to put (sell) the bond back to the issuer at face value in the event of the bondholder's death or legal incapacitation. This is also known as a "survivor's option".

- Sinking fund provision of the corporate bond indenture requires a certain portion of the issue to be retired periodically. The entire bond issue can be liquidated by the maturity date; if not, the remainder is called balloon maturity. Issuers may either pay to trustees, which in turn call randomly selected bonds in the issue, or, alternatively, purchase bonds in the open market, then return them to trustees.

Types

[edit]

Bonds can be categorised in several ways, such as the type of issuer, the currency, the term of the bond (length of time to maturity) and the conditions applying to the bond. The following descriptions are not mutually exclusive, and more than one of them may apply to a particular bond:

The nature of the issuer and the security offered

[edit]The nature of the issuer will affect the security (certainty of receiving the contracted payments) offered by the bond, and sometimes the tax treatment.

- Government bonds, often also called treasury bonds, are issued by a sovereign national government.[10] Some countries have repeatedly defaulted on their government bonds, while some other treasury bonds have been treated as risk-free and not exposed to default risk. Risk-free bonds are the safest bonds, with the lowest interest rate. A Treasury bond is backed by the "full faith and credit" of the relevant government. However, in reality most or all government bonds do carry some residual risk. This is indicated by

- the award by rating agencies of a rating below the top rating,

- bonds issued by different national governments, such as various member states of the European Union, all denominated in Euros, offering different market yields reflecting their different risks.

- A supranational bond, also known as a "supra", is issued by a supranational organisation like the World Bank. They have a very good credit rating, similar to that on national government bonds.

- A municipal bond issued by a local authority or subdivision within a country,[10] for example a city or a federal state. These will to varying degrees carry the backing of the national government. In the United States, such bonds are exempt from certain taxes. For example, Build America Bonds (BABs) are a form of municipal bond authorized by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Unlike traditional US municipal bonds, which are usually tax exempt, interest received on BABs is subject to federal taxation. However, as with municipal bonds, the bond is tax-exempt within the US state where it is issued. Generally, BABs offer significantly higher yields than standard municipal bonds.

- A revenue bond is a special type of municipal bond distinguished by its guarantee of repayment solely from revenues generated by a specified revenue-generating entity associated with the purpose of the bonds. Revenue bonds are typically "non-recourse", meaning that in the event of default, the bond holder has no recourse to other governmental assets or revenues.

- A War bond is a bond issued by a government to fund military operations and other expenditure during wartime. It will often have a low return rate, and so can be bought due to a lack of opportunities or patriotism.

- Corporate bonds are issued by corporations.[10]

- High-yield bonds (junk bonds) are bonds that are rated below investment grade by the credit rating agencies, because they are uncertain that the issuer will be able or willing to pay the scheduled interest payments and/or redeem the bond at maturity. As these bonds are much riskier than investment grade bonds, investors expect to earn a much higher yield.

- A climate bond is a bond issued by a government or corporate entity in order to raise finance for climate change mitigation- or adaptation-related projects or programmes. For example, in 2021 the UK government started to issue "green bonds".

- Asset-backed securities are bonds whose interest and principal payments are backed by underlying cash flows from other assets. Examples of asset-backed securities are mortgage-backed securities (MBSs), collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs).

- Covered bonds are backed by cash flows from mortgages or public sector assets. Unlike asset-backed securities, the assets for such bonds remain on the issuer's balance sheet.

- Subordinated bonds are those that have a lower priority than other bonds of the issuer in case of liquidation. In case of bankruptcy, there is a hierarchy of creditors. First the liquidator is paid, then government taxes, etc. The first bond holders in line to be paid are those holding what are called senior bonds. After they have been paid, the subordinated bond holders are paid. As a result, the risk is higher. Therefore, subordinated bonds usually have a lower credit rating than senior bonds. The main examples of subordinated bonds can be found in bonds issued by banks and asset-backed securities. The latter are often issued in tranches. The senior tranches get paid back first, the subordinated tranches later.

- Social impact bonds are an agreement for public sector entities to pay back private investors after meeting verified improved social outcome goals that result in public sector savings from innovative social program pilot projects.

The term of the bond

[edit]- Most bonds are structured to mature on a stated date, when the principal is due to be repaid, and interest payments cease. Typically, a bond with term to maturity of under five years would be called a short bond; 5 to 15 years would be "medium", and over 15 years would be "long"; but the numbers may vary in different markets.

- Perpetual bonds are also often called perpetuities or 'Perps'. They have no maturity date. Historically the most famous of these were the UK Consols (there were also some other perpetual UK government bonds, such as War Loan, Treasury Annuities and undated Treasuries). Some of these were issued back in 1888 or earlier. There had been insignificant quantities of these outstanding for decades, and they have now been fully repaid. Some ultra-long-term bonds (sometimes a bond can last centuries: West Shore Railroad issued a bond which matures in 2361 (i.e. 24th century)) are virtually perpetuities from a financial point of view, with the current value of principal near zero.

- The Methuselah is a type of bond with a maturity of 50 years or longer.[11] The term is a reference to Methuselah, the oldest person whose age is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. The issuance of Methuselahs has been increasing in recent years due to demand for longer-dated assets from pension plans, particularly in France and the United Kingdom. Issuance of Methuselahs in the United States has been limited, however: the U.S. Treasury does not currently issue Treasuries with maturities beyond 30 years, which would serve as a reference level for any corporate issuance.

- A Serial bond is a bond that matures in installments over a period of time. For example, a $100,000, 5-year serial bond might pay $20,000 per year.

The conditions applying to the bond

[edit]

- Fixed rate bonds have interest payments ("coupon"), usually semi-annual, that remains constant throughout the life of the bond. Other variations include stepped-coupon bonds, whose coupon increases during the life of the bond.

- Floating rate notes (FRNs, floaters) have a variable coupon that is linked to a reference rate of interest, such as Libor or Euribor. For example, the coupon may be defined as three-month USD LIBOR + 0.20%. The coupon rate is recalculated periodically, typically every one or three months.

- Zero-coupon bonds (zeros) pay no regular interest. They are issued at a substantial discount to par value, so that the interest is effectively rolled up to maturity (and usually taxed as such). The bondholder receives the full principal amount on the redemption date. An example of zero coupon bonds is Series E savings bonds issued by the U.S. government. Zero-coupon bonds may be created from fixed rate bonds by a financial institution separating ("stripping off") the coupons from the principal. This can create a "Principal Only" zero-coupon bond and an "Interest Only" (IO) strip bond from the original fixed income bond.

- Inflation-indexed bonds (linkers) (US) or index-linked bonds (UK), in which the principal amount and the interest payments are indexed to the level of consumer prices. The interest rate is normally lower than for fixed rate bonds with a comparable maturity (this relationship briefly reversed for short-term UK bonds in December 2008). Higher inflation rates increase the nominal principal and coupon amounts paid on these bonds. The United Kingdom was the first sovereign issuer to issue inflation-linked gilts in the 1980s. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) and I-bonds are examples of inflation-linked bonds issued by the U.S. government.

- Other indexed bonds, for example equity-linked notes and bonds indexed on a business indicator (income, added value) or on a country's GDP.

- Lottery bonds are issued by European and other states. Interest is paid as on a traditional fixed rate bond, but the issuer will redeem randomly selected individual bonds within the issue according to a schedule. Some of these redemptions will be for a higher value than the face value of the bond.

Bonds with embedded options for the holder

[edit]- Convertible bonds let a bondholder exchange a bond to a number of shares of the issuer's common stock. These are known as hybrid securities, because they combine equity and debt features.

- Exchangeable bonds allows for exchange to shares of a corporation other than the issuer.

Documentation and evidence of title

[edit]

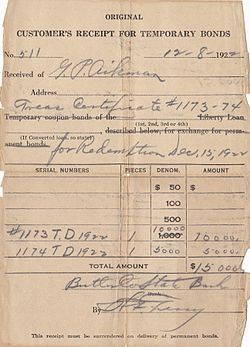

- A bearer bond is an official certificate issued without a named holder. In other words, the person who has the paper certificate can claim the value of the bond. Often they are registered by a number to prevent counterfeiting, but may be traded like cash. Bearer bonds are very risky because they can be lost or stolen, due to the fact that they can be claimed by whoever is in possession of them.[12] In some countries they were historically popular because the owner could not be traced by the tax authorities. For example, after federal income tax began in the United States, bearer bonds were seen as an opportunity to conceal income or assets.[13] U.S. corporations stopped issuing bearer bonds in the 1960s, the U.S. Treasury stopped in 1982, and state and local tax-exempt bearer bonds were prohibited in 1983.[14]

- A registered bond is a bond whose ownership (and any subsequent purchaser) is recorded by the issuer, or by a transfer agent. Interest payments and the principal upon maturity are sent to the registered owner. The owner can continue to receive interest with a duplicated bond in case of a loss. However, the bond is not easily transferable to other people. Registered bonds seldom appeared in the market for trading. The traceability of the bonds means it has a minor effect on bond prices. Once a new owner acquired the bond, the old bond must be sent to the corporation or agent for cancellation and for issuance of a new bond.[1] It is the opposite of a bearer bond.

- A book-entry bond is a bond that does not have a paper certificate. As physically processing paper bonds and interest coupons became more expensive, issuers (and banks that used to collect coupon interest for depositors) have tried to discourage their use. Some book-entry bond issues do not offer the option of a paper certificate, even to investors who prefer them.[15]

Retail bonds

[edit]- Retail bonds are a type of corporate bond mostly designed for ordinary investors.[16]

Foreign currencies

[edit]Some companies, banks, governments, and other sovereign entities may decide to issue bonds in foreign currencies as the foreign currency may appear to potential investors to be more stable and predictable than their domestic currency. Issuing bonds denominated in foreign currencies also gives issuers the ability to access investment capital available in foreign markets.

A downside is that the government loses the option to reduce its bond liabilities by inflating its domestic currency.

The proceeds from the issuance of these bonds can be used by companies to break into foreign markets, or can be converted into the issuing company's local currency to be used on existing operations through the use of foreign exchange swap hedges. Foreign issuer bonds can also be used to hedge foreign exchange rate risk. Some foreign issuer bonds are called by their nicknames, such as the "samurai bond". These can be issued by foreign issuers looking to diversify their investor base away from domestic markets. These bond issues are generally governed by the law of the market of issuance, e.g., a samurai bond, issued by an investor based in Europe, will be governed by Japanese law. Not all of the following bonds are restricted for purchase by investors in the market of issuance.

Bond valuation

[edit]The market price of a bond is the present value of all expected future interest and principal payments of the bond, here discounted at the bond's yield to maturity (i.e. rate of return). That relationship is the definition of the redemption yield on the bond, which is likely to be close to the current market interest rate for other bonds with similar characteristics, as otherwise there would be arbitrage opportunities. The yield and price of a bond are inversely related so that when market interest rates rise, bond prices fall and vice versa. For a discussion of the mathematics see Bond valuation.

The bond's market price is usually expressed as a percentage of nominal value: 100% of face value, "at par", corresponds to a price of 100; prices can be above par (bond is priced at greater than 100), which is called trading at a premium, or below par (bond is priced at less than 100), which is called trading at a discount. The market price of a bond may be quoted including the accrued interest since the last coupon date. (Some bond markets include accrued interest in the trading price and others add it on separately when settlement is made.) The price including accrued interest is known as the "full" or "dirty price". (See also Accrual bond.) The price excluding accrued interest is known as the "flat" or "clean price".

Most government bonds are denominated in units of $1000 in the United States, or in units of £100 in the United Kingdom. Hence, a deep discount US bond, selling at a price of 75.26, indicates a selling price of $752.60 per bond sold. (Often, in the US, bond prices are quoted in points and thirty-seconds of a point, rather than in decimal form.) Some short-term bonds, such as the U.S. Treasury bill, are always issued at a discount, and pay par amount at maturity rather than paying coupons. This is called a discount bond.

Although bonds are not necessarily issued at par (100% of face value, corresponding to a price of 100), their prices will move towards par as they approach maturity (if the market expects the maturity payment to be made in full and on time) as this is the price the issuer will pay to redeem the bond. This is referred to as "pull to par". At the time of issue of the bond, the coupon paid, and other conditions of the bond, will have been influenced by a variety of factors, such as current market interest rates, the length of the term and the creditworthiness of the issuer. These factors are likely to change over time, so the market price of a bond will vary after it is issued. (The position is a bit more complicated for inflation-linked bonds.)

The interest payment ("coupon payment") divided by the current price of the bond is called the current yield (this is the nominal yield multiplied by the par value and divided by the price). There are other yield measures that exist such as the yield to first call, yield to worst, yield to first par call, yield to put, cash flow yield and yield to maturity. The relationship between yield and term to maturity (or alternatively between yield and the weighted mean term allowing for both interest and capital repayment) for otherwise identical bonds derives the yield curve, a graph plotting this relationship.

If the bond includes embedded options, the valuation is more difficult and combines option pricing with discounting. Depending on the type of option, the option price as calculated is either added to or subtracted from the price of the "straight" portion. See further under Bond option § Embedded options. This total is then the value of the bond. More sophisticated lattice- or simulation-based techniques may (also) be employed.

Bond markets, unlike stock or share markets, sometimes do not have a centralized exchange or trading system. Rather, in most developed bond markets such as the U.S., Japan and western Europe, bonds trade in decentralized, dealer-based over-the-counter markets. In such a market, liquidity is provided by dealers and other market participants committing risk capital to trading activity. In the bond market, when an investor buys or sells a bond, the counterparty to the trade is almost always a bank or securities firm acting as a dealer. In some cases, when a dealer buys a bond from an investor, the dealer carries the bond "in inventory", i.e. holds it for their own account. The dealer is then subject to risks of price fluctuation. In other cases, the dealer immediately resells the bond to another investor.

Investing in bonds

[edit]Bonds are bought and traded mostly by institutions like central banks, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds, and banks. Insurance companies and pension funds have liabilities which essentially include fixed amounts payable on predetermined dates. They buy the bonds to match their liabilities, and may be compelled by law to do this. Most individuals who want to own bonds do so through bond funds. Still, in the U.S., nearly 10% of all bonds outstanding are held directly by households.

The volatility of bonds (especially short and medium dated bonds) is lower than that of equities (stocks). Thus, bonds are generally viewed as safer investments than equities, but this perception is only partially correct. Bonds do suffer from less day-to-day volatility than stocks, and bonds' interest payments are sometimes higher than the general level of dividend payments. Bonds are often liquid – it is often fairly easy for an institution to sell a large quantity of bonds without affecting the price much, which may be more difficult for equities – and the comparative certainty of a fixed interest payment twice a year and a fixed lump sum at maturity is attractive. Bondholders also enjoy a measure of legal protection: under the law of most countries, if a company goes bankrupt, its bondholders will often receive some money back (the recovery amount), whereas the company's equity stock often ends up valueless. However, bonds can also be risky but less risky than stocks:

- Fixed rate bonds are subject to interest rate risk, meaning that their market prices will decrease in value when the generally prevailing interest rates rise. Since the payments are fixed, a decrease in the market price of the bond means an increase in its yield. When the market interest rate rises, the market price of bonds will fall, reflecting investors' ability to get a higher interest rate on their money elsewhere—perhaps by purchasing a newly issued bond that already features the newly higher interest rate. This does not affect the interest payments to the bondholder, so long-term investors who want a specific amount at the maturity date do not need to worry about price swings in their bonds and do not suffer from interest rate risk.

Bonds are also subject to various other risks such as call and prepayment risk, credit risk, reinvestment risk, liquidity risk, event risk, exchange rate risk, volatility risk, inflation risk, sovereign risk and yield curve risk. Again, some of these will only affect certain classes of investors.

Price changes in a bond will immediately affect mutual funds that hold these bonds. If the value of the bonds in their trading portfolio falls, the value of the portfolio also falls. This can be damaging for professional investors such as banks, insurance companies, pension funds and asset managers (irrespective of whether the value is immediately "marked to market" or not). If there is any chance a holder of individual bonds may need to sell their bonds and "cash out", interest rate risk could become a real problem, conversely, bonds' market prices would increase if the prevailing interest rate were to drop, as it did from 2001 through 2003. One way to quantify the interest rate risk on a bond is in terms of its duration. Efforts to control this risk are called immunization or hedging.

- Bond prices can become volatile depending on the credit rating of the issuer – for instance if the credit rating agencies like Standard & Poor's and Moody's upgrade or downgrade the credit rating of the issuer. An unanticipated downgrade will cause the market price of the bond to fall. As with interest rate risk, this risk does not affect the bond's interest payments (provided the issuer does not actually default), but puts at risk the market price, which affects mutual funds holding these bonds, and holders of individual bonds who may have to sell them.

- A company's bondholders may lose much or all their money if the company goes bankrupt. Under the laws of many countries (including the United States and Canada), bondholders are in line to receive the proceeds of the sale of the assets of a liquidated company ahead of some other creditors. Bank lenders, deposit holders (in the case of a deposit taking institution such as a bank) and trade creditors may take precedence.

There is no guarantee of how much money will remain to repay bondholders. As an example, after an accounting scandal and a Chapter 11 bankruptcy at the giant telecommunications company Worldcom, in 2004 its bondholders ended up being paid 35.7 cents on the dollar.[17] In a bankruptcy involving reorganization or recapitalization, as opposed to liquidation, bondholders may end up having the value of their bonds reduced, often through an exchange for a smaller number of newly issued bonds.

- Some bonds are callable, meaning that even though the company has agreed to make payments plus interest towards the debt for a certain period of time, the company can choose to pay off the bond early. This creates reinvestment risk, meaning the investor is forced to find a new place for their money, and the investor might not be able to find as good a deal, especially because this usually happens when interest rates are falling.

Bond indices

[edit]A number of bond indices exist for the purposes of managing portfolios and measuring performance, similar to the S&P 500 or Russell Indexes for companies' shares. The most common American benchmarks are the Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate (ex Lehman Aggregate), Citigroup BIG and Merrill Lynch Domestic Master. Most indices are parts of families of broader indices that can be used to measure global bond portfolios, or may be further subdivided by maturity or sector for managing specialized portfolios.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Chorafas, Dimitris N (2005). The management of bond investments and trading of debt. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 49–50. ISBN 9780080497280. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ Bonds Archived 2012-07-18 at the Wayback Machine, accessed: 2012-06-08

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "bond". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

- ^ William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice Archived 2022-05-23 at the Wayback Machine (c. 1596–1599), Act I, scene iii: "Three thousand ducats. I think I may take his bond". John Heminges and Henry Condell (eds.), Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (London: Blount and Jaggard, 1623).

- ^ "UK Debt Management Office". Dmo.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-04-04. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ "Affordable Housing Finance". Housingfinance.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ^ Thau, Annette (2001). The Bond Book (Revised ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 56. ISBN 0-07-135862-5.

- ^ Thau op cit p. 58-59.

- ^ Fabozzi, Frank J. (1996). Bond Markets, Analysis and Strategies (third ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 44. ISBN 0-13-339151-5.

- ^ a b c Thau, Annette (2010). The Bond Book, Third Edition: Everything Investors Need to Know About Treasuries, Municipals, GNMAs, Corporates, Zeros, Bond Funds, Money Market Funds, and More (Third ed.). McGraw Hill Professional. p. 5. ISBN 9780071713092. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Anne Padieu "Quand les États sont tentés par la dette «Mathusalem» " Agence France-Presse à Paris / Le Devoir, 23 août 2019 Archived 2019-08-29 at the Wayback Machine: discussion of 100-year maturity bonds (in French).

- ^ "Bearer Bond: Definition, How It Works, and Why They're Valuable". Investopedia. Retrieved 2025-05-22.

- ^ Eason, Yla (June 6, 1983). "Final Surge in Bearer Bonds" New York Times.

- ^ Quint, Michael (August 14, 1984). "Elements in Bearer Bond Issue". New York Times.

- ^ no byline (July 18, 1984). "Book Entry Bonds Popular". New York Times.

- ^ "EnQuest CFO Swinney Issues First Industrial Retail Bond". CFO Insight. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ "More worthless WorldCom stock". bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-24. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

External links

[edit]Bond (finance)

View on GrokipediaA bond is a debt security representing a loan made by an investor to a borrower, typically a government, corporation, or municipality, in exchange for periodic interest payments and repayment of the principal at maturity.[1] Borrowers issue bonds to finance operations, projects, or deficits, while investors seek predictable income streams and preservation of capital relative to equities.[1] Bonds encompass diverse types, including U.S. Treasury securities (bills, notes, and bonds), which are backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government; corporate bonds issued by businesses to fund expansion or operations; and municipal bonds from state or local governments often used for infrastructure.[1] Other variants include agency bonds from government-sponsored enterprises, high-yield (junk) bonds from riskier issuers offering higher returns, and inflation-linked bonds like Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS).[1] The global fixed income market, dominated by bonds, stood at approximately $145 trillion outstanding in 2024, underscoring their centrality to capital allocation and economic activity.[2] The mechanics of bonds involve a face value (principal), coupon rate (interest paid periodically), and maturity date when principal is repaid; bond prices fluctuate inversely with interest rates, as rising rates diminish the present value of future payments.[3] Yields, which reflect total return accounting for price changes, serve as benchmarks for risk-free rates (e.g., Treasuries) and credit spreads for riskier debt.[1] Investors face key risks including credit (default) risk, where issuers fail to meet obligations—minimal for Treasuries but elevated for high-yield bonds—and interest rate risk, where price declines occur amid rate hikes, particularly for longer-maturity bonds.[1][3] Despite these, bonds provide diversification, income stability, and liquidity in secondary markets, forming a cornerstone of institutional and retail portfolios.[1]

Definition and Fundamentals

Core Definition and Distinctions

A bond is a debt security representing a loan made by an investor to a borrower, typically a government, corporation, municipality, or other entity, in exchange for periodic interest payments and the return of the principal amount at maturity. The issuer uses the proceeds to finance operations, projects, or other capital needs, while the bondholder acts as a creditor rather than an owner. Unlike equity investments, bonds do not confer voting rights or claims to residual profits, but they provide contractual obligations for repayment, with interest rates often fixed at issuance to reflect prevailing market conditions and the issuer's creditworthiness.[4][5][6] Key elements of a bond include its face value (or par value), the principal amount repaid at maturity; the coupon rate, which determines the interest payments (e.g., semi-annual payments calculated as a percentage of face value); and the maturity date, ranging from short-term (under one year) to long-term (over 30 years), at which the issuer redeems the bond. Bonds are usually issued in denominations of $1,000 or multiples thereof and can be traded on secondary markets, where their prices fluctuate based on interest rate changes, issuer credit risk, and economic conditions—trading at a premium, discount, or par relative to face value. Zero-coupon bonds, by contrast, pay no periodic interest but are sold at a deep discount and redeemed at face value, with the difference representing imputed interest.[7][4] Bonds differ fundamentally from stocks, which represent equity ownership in a company with potential for dividends and capital appreciation but no guaranteed returns or repayment. Bondholders have priority over stockholders in bankruptcy proceedings, receiving claims on assets before equity holders, though they face risks like default (failure to pay interest or principal) or interest rate risk (where rising rates decrease bond prices). In contrast to bank loans, bonds are publicly marketable securities standardized for broader investor access, often regulated by bodies like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, whereas loans are typically bilateral and less liquid. Government bonds, such as U.S. Treasuries, are distinguished by sovereign backing and lower default risk compared to corporate bonds, which depend on the issuer's financial health and may offer higher yields to compensate for greater risk.[8][9][5]Etymology and Terminology Evolution

The term "bond" derives from the Old English band, meaning a fetter or chain that binds, which entered Middle English around the 13th century as bond or band, signifying anything that ties or restrains.[10] In legal contexts, this evolved to describe a formal written instrument under seal, obligating the signer to pay a specified sum or perform a duty, with records of such usage appearing by the late 14th century in English documents referring to personal sureties or debts.[11] The financial application emerged in the 16th century, denoting a documentary obligation to repay principal and interest, reflecting the binding commitment of the issuer to the holder, distinct from informal loans or promissory notes.[10] By the 17th century, amid the development of organized public debt markets in the Netherlands and England—such as the Dutch East India Company's 1623 perpetual bonds and England's Exchequer orders—the term "bond" standardized for transferable securities evidencing government or corporate borrowings with fixed maturities and coupons.[12] This usage contrasted with earlier terminology like "annuities" or "tallies" (notched sticks for debt records in medieval England), emphasizing negotiability and standardization over personal pledges. In the American colonies, bonds appeared in 18th-century state debt issuances, such as South Carolina's 1777 consolidation bonds, formalizing the term for funded debts post-independence.[13] Terminology evolution reflected market innovations and legal refinements: "debenture," from Latin debentur ("these are due," from medieval ledger entries), denoted unsecured bonds by the 15th century, gaining prominence in 19th-century corporate finance for claims without specific collateral. Shorter-term instruments became "notes" (from Latin nota, a mark or record, evolving to promissory evidences by the 18th century), while perpetual bonds retained names like "consols" (consolidated annuities, issued by Britain in 1751). 20th-century developments introduced subtypes such as "zero-coupon bonds" (named for absent periodic payments, popularized in the 1980s via STRIPS programs) and "junk bonds" (coined in the 1970s-1980s for high-yield, high-risk issues, attributed to analysts like Hyman Minsky though formalized by Michael Milken's campaigns).[14] These distinctions arose from regulatory needs and investor demands for precision, yet "bond" persists as the umbrella term for fixed-income debt securities, underscoring the enduring metaphor of contractual bondage.[15]Historical Development

Ancient and Early Modern Origins

Although private lending and debt obligations appeared in ancient civilizations, including Mesopotamia where clay tablets recorded promises to repay grain or silver from around 2000 BC, these were personal contracts rather than standardized, transferable securities akin to modern bonds.[16] Similarly, ancient Athens financed military needs through public contributions, such as the funds raised by Themistocles in 485 BC from Laurion silver mines to build warships against Persia, but these resembled one-off levies backed by state revenues rather than marketable debt instruments.[17] The emergence of true bonds occurred in medieval Italy amid rising needs for war finance and trade. The Republic of Venice issued the first recorded government bonds in 1172 as prestiti, interest-bearing forced loans from wealthy citizens to fund naval campaigns, which evolved into voluntary, perpetual securities paying 4-5% annually and backed by customs duties.[18] These prestiti became tradable by the early 13th century, with a secondary market forming on the Rialto Bridge, allowing holders to sell claims transferable by endorsement.[19] Comparable systems arose in Genoa (luoghi) and Florence (monti), where public debt consolidated into funded obligations subscribed by citizens and foreigners, often yielding 5-7% and secured by excise taxes or urban revenues, fostering early capital markets in the 13th-14th centuries.[20] In the early modern era, bond issuance expanded with state formation and commerce. The Dutch provinces, facing Spanish Habsburg wars, issued obligatiën through the States of Holland from the 1510s, with yields around 10-12% initially, traded on emerging exchanges; by 1609, the Amsterdam Wisselbank facilitated bond settlements, enhancing liquidity.[12] The Dutch East India Company (VOC) issued corporate bonds starting in 1623, such as the 8% bonds sold in Middelburg and Amsterdam to finance expeditions, marking the first widespread use of fixed-income securities by a joint-stock entity.[21] In England, post-1688 Glorious Revolution, the government funded deficits via Bank of England bonds from 1693, including redeemable annuities at 8% rising to 14% during wars, which traded actively and laid groundwork for consolidated national debt.[22] These innovations reflected causal shifts toward representative institutions committing to repayment, reducing default risks compared to absolutist defaults like Spain's multiple quiebras in the 16th-17th centuries.[12]Emergence in Capitalist Economies

The emergence of bonds in capitalist economies aligned with the rise of mercantile trade and joint-stock enterprises in the 17th-century Dutch Republic, where public debt instruments facilitated large-scale ventures beyond personal wealth. The Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), chartered on March 20, 1602, supplemented its equity financing with bonds to fund expeditions to Asia, raising initial capital equivalent to about 6.4 million guilders through shares while issuing debt securities that traded on the Amsterdam exchange.[23][24] These bonds distributed risks of long-distance commerce among investors, enabling sustained capital flows and the development of secondary markets that underpinned early capitalist expansion.[18] In England, bonds gained prominence after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which bolstered creditor protections and allowed the government to issue funded debt reliably for warfare and public works. The Bank of England, founded in 1694, issued lottery loans and annuities that evolved into consolidated bonds, with the first consols appearing in 1751 at a 3.5% coupon rate to refinance existing debts.[25][26] These perpetual securities provided stable, long-term financing, absorbing domestic savings and reducing reliance on short-term borrowing amid growing commercial activity. During the Industrial Revolution, British sovereign bonds played a causal role in reallocating resources toward manufacturing; high public debts from the Napoleonic Wars, totaling over 200% of GDP by 1815, prompted tax reforms and enabled landowners to liquidate agricultural assets via consol purchases, freeing capital for industrial investments.[27][28] This mechanism, where postwar consol price surges created a wealth effect for rentiers, accelerated structural shifts from agrarian to factory-based production, with bond yields falling from around 5% in the late 18th century to lower levels by the 1820s.[29] In the United States, similar dynamics emerged post-independence, as federal bonds financed infrastructure like canals and railroads, issuing over $200 million in securities by the 1830s to support nascent capitalist growth.[30]20th-Century Expansion and Innovations

The 20th century witnessed significant expansion in bond markets, driven primarily by government issuances to finance the two world wars. During World War I, the United States issued Liberty Bonds, raising approximately $22 billion—equivalent to over $5 trillion in contemporary terms—through five drives between 1917 and 1919, with at least one-third of Americans aged 18 or older participating.[31] These bonds transformed American finance by broadening securities market participation and spurring the growth of investment banks, which numbered over 6,000 by 1929.[32] In World War II, the U.S. launched Series E Defense Savings Bonds in 1941 amid rapid public debt expansion due to defense spending, which helped finance the war effort while curbing inflation by absorbing excess liquidity.[33][34] Post-war periods saw continued growth in bond issuance across government, municipal, and corporate sectors. Long-term U.S. government bond yields peaked at 15% in 1981 before declining to 6% by century's end, reflecting maturing markets and investor shifts, though equities generally outperformed bonds over the era.[35] Municipal bond markets innovated with the emergence of bond counsel in the early 20th century to assure investors of tax-exempt status and legal validity, becoming a standard practice that supported infrastructure financing.[36] Globally, bond markets expanded as economies industrialized, with securities trading mechanics evolving on exchanges like the NYSE and over-the-counter markets.[37] Key innovations reshaped bond structures and accessibility. The Eurobond market originated in 1963 with a $15 million issuance by Italy's Autostrade for its motorway network, denominated in U.S. dollars and sold internationally to circumvent domestic regulations and capitalize on lower borrowing costs amid U.S. interest equalization taxes.[38] This market grew exponentially, fostering global finance by enabling cross-border capital flows outside national currencies.[39] In the 1980s, original-issue high-yield bonds, dubbed "junk bonds," proliferated under figures like Michael Milken at Drexel Burnham Lambert, expanding from $10 billion outstanding in 1977 to $189 billion by 1989, primarily funding leveraged buyouts and mergers for non-investment-grade issuers.[40][41] These developments, concentrated in the century's final decades, introduced greater flexibility in fixed-income instruments compared to prior eras.[35]Issuance Mechanisms

Primary Market Processes

The primary market for bonds involves the initial issuance and sale of newly created debt securities directly from issuers to investors, enabling governments, corporations, and other entities to raise capital for funding deficits, projects, or operations. Unlike the secondary market, where existing bonds are traded among investors, primary market transactions establish the bond's terms, pricing, and initial ownership, with proceeds flowing to the issuer rather than prior holders.[42] This process typically requires regulatory compliance, such as filing prospectuses with bodies like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for public offerings, to disclose risks, financials, and terms.[43] For government bonds, particularly U.S. Treasuries, issuance occurs through competitive auctions managed by the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Auctions are announced in advance via TreasuryDirect, specifying the security type (e.g., bills, notes, bonds), amount, maturity, and bidding deadline; non-competitive bids from individuals or small entities are accepted first at the average yield determined by competitive bids, followed by competitive bids from primary dealers and institutions specifying desired yields.[44] The process uses a uniform-price (Dutch) auction format, where all successful bidders pay the same price based on the highest accepted yield, minimizing financing costs and ensuring broad participation; for example, as of 2024, Treasury auctions occur regularly, with bills auctioned weekly and longer-term securities quarterly.[45] Primary dealers, a group of about 24 major banks designated by the Federal Reserve, are required to bid and help distribute securities, promoting liquidity.[46] Corporate bond issuance in the primary market predominantly relies on underwriting by investment banks, structured as firm commitment deals where underwriters purchase the bonds from the issuer at a discount and resell them to investors, bearing the risk of unsold inventory.[47] The process unfolds in phases: initial planning with advisors to assess market conditions and structure (e.g., coupon rate, maturity); due diligence and SEC registration via Form S-3 for shelf offerings allowing rapid issuance; roadshows to gauge investor demand through book-building; and final pricing based on order books, often at a spread over benchmarks like Treasuries.[48] In 2023, U.S. corporate bond issuance exceeded $1.5 trillion, with investment-grade bonds comprising the majority, facilitated by syndicates of banks to spread risk.[49] Municipal bonds, issued by state and local governments, employ either competitive bidding—where underwriters submit sealed bids for the issue—or negotiated sales with pre-selected underwriters, depending on market conditions and issuer preferences; competitive sales, used for about 20-30% of issues, aim to secure the lowest interest cost by pitting bidders against each other.[50] The full cycle includes assembling a financing team (e.g., bond counsel, financial advisors), legal structuring, and official statements akin to prospectuses, with post-issuance continuing disclosure required under SEC Rule 15c2-12.[43] Alternative primary market channels include private placements, where bonds are sold directly to a limited number of institutional investors without public registration, exempt under SEC Regulation D; this method, comprising roughly 10-15% of U.S. corporate debt issuance, offers speed and confidentiality but lower liquidity.[51] Across all types, primary market efficiency hinges on transparent pricing mechanisms and investor access, with electronic platforms like Treasury Automated Auction Processing System (TAAPS) streamlining bids since the 1990s.[52]Differences by Issuer Type

Bonds differ significantly by issuer type, primarily in terms of credit risk, tax treatment, yield profiles, liquidity, and regulatory oversight, reflecting the varying capacities and incentives of issuers to meet obligations. Sovereign bonds, issued by national governments such as U.S. Treasuries, are backed by the full faith and credit of the issuing authority, including taxing powers and central bank support, resulting in the lowest default risk among major bond categories; for instance, U.S. Treasuries have never defaulted on principal or interest payments since their inception in 1790. Municipal bonds, issued by state, local, or territorial governments to fund public projects like infrastructure, carry intermediate risk backed either by general taxing authority (general obligation bonds) or specific revenue streams (revenue bonds), with historical default rates significantly lower than corporate bonds—averaging 0.08% annually from 1970 to 2020 compared to higher corporate rates.[53] Corporate bonds, issued by private companies to finance operations or expansions, exhibit the highest credit risk among investment-grade issuers, dependent on the firm's profitability and assets, leading to default rates that averaged 1.5% annually for U.S. investment-grade corporates from 1981 to 2022.[4] Tax treatment varies markedly, influencing after-tax yields and investor preferences. Interest on sovereign bonds like U.S. Treasuries is subject to federal income tax but exempt from state and local taxes, enhancing appeal for residents of high-tax states.[54] Municipal bond interest is generally exempt from federal income tax, and often from state and local taxes if the holder resides in the issuing jurisdiction, providing a tax-equivalent yield advantage for high-income investors—though private activity bonds may be subject to the alternative minimum tax.[55] Corporate bond interest is fully taxable at federal, state, and local levels, reducing net returns for taxable accounts but allowing for potentially higher pre-tax yields to compensate.[56] Yields reflect these risk and tax differentials, with sovereign bonds offering benchmark rates (e.g., the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield averaged 2.9% from 2000 to 2023), municipal yields typically 20-30% lower on a pre-tax basis due to tax benefits, and corporate yields adding a credit spread—investment-grade corporates yielding 1-2% above Treasuries as of 2023 to account for default risk.[57] Liquidity also differs: corporate bonds trade more frequently in secondary markets due to broader investor bases and standardized issuance, while municipal bonds often exhibit lower trading volumes and wider bid-ask spreads, partly from fragmented issuer diversity exceeding 50,000 entities.[53] Regulatory requirements further diverge; corporate issuers must comply with Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registration and periodic disclosures under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, municipal issuers face lighter federal oversight via the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) but varying state rules, and sovereign issuers operate under minimal external regulation beyond market discipline.[5][55]| Issuer Type | Primary Backing | Default Risk Profile | Tax Treatment of Interest | Typical Yield Premium Over Sovereign |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sovereign (e.g., U.S. Treasury) | Full faith, credit, and taxing power | Lowest; near-zero historical defaults | Federal taxable; state/local exempt | Benchmark (0%)[4] |

| Municipal | Taxing authority or project revenue | Low; 0.08% annual default rate (1970-2020) | Often federal-exempt; state-exempt if in-state | Lower pre-tax; higher tax-equivalent[53][55] |

| Corporate | Issuer's cash flows and assets | Higher; 1.5% annual for investment-grade (1981-2022) | Fully taxable (federal, state, local) | 1-2% spread for investment-grade[57][56] |

Essential Features

Principal, Maturity, and Coupon Structure

The principal, also termed the face value or par value, constitutes the nominal amount that the bond issuer commits to repay the bondholder upon maturity, serving as the foundational sum borrowed and returned in full at the bond's term end.[58] This value is typically standardized, such as $1,000 per bond for many U.S. corporate and Treasury securities, and forms the basis for interest computations unless specified otherwise in the bond's terms.[5] In amortizing bonds, portions of the principal may be repaid periodically alongside interest, reducing the outstanding balance over time, though most conventional bonds maintain the full principal until maturity.[59] Maturity refers to the predetermined date when the issuer repays the principal in full, accompanied by the final interest payment, marking the bond's expiration and the cessation of any ongoing obligations absent default.[4] Bonds are categorized by maturity duration: short-term (original term of one year or less, often akin to money market instruments), intermediate-term (1 to 10 years), and long-term (exceeding 10 years, extending investor exposure to interest rate fluctuations).[60] Serial bonds feature staggered maturities across multiple dates for principal portions, facilitating phased repayment, whereas term bonds concentrate the entire principal repayment on a single maturity date.[61] Investors holding to maturity receive the par value regardless of interim price volatility, provided the issuer remains solvent. The coupon structure delineates the interest payment schedule and rate applied to the principal, with standard coupon bonds delivering periodic payments—frequently semi-annually—calculated as the coupon rate multiplied by the face value divided by the payment frequency.[62] Fixed-rate coupons maintain a constant yield throughout the bond's life, offering predictable income, as seen in most Treasury and corporate issuances.[63] Floating-rate structures adjust payments periodically based on a reference index like SOFR plus a spread, mitigating interest rate risk for holders.[64] Zero-coupon bonds forgo interim payments entirely, instead sold at a deep discount to par and accreting value to the principal at maturity through implied interest, appealing for deferred taxation in certain jurisdictions. Step-up coupons escalate the rate at predefined intervals, often to compensate for call risk or credit deterioration.[65] These elements collectively define the bond's cash flow profile, influencing its valuation and suitability for investors seeking stability or yield enhancement.[66]Yield Calculation, Pricing, and Credit Assessment

Bond yields represent the effective return to investors, incorporating both periodic interest payments and any capital gain or loss upon maturity. The current yield is a simple metric calculated as the bond's annual coupon payment divided by its current market price, providing a snapshot of income return relative to price but ignoring capital appreciation or depreciation.[67][68] For instance, a bond with a $50 annual coupon trading at $1,000 yields 5%, but this measure assumes holding only for one year and reinvestment at the same rate, rendering it incomplete for long-term analysis.[67] The yield to maturity (YTM) serves as the comprehensive standard, defined as the internal rate of return equating the bond's current price to the present value of its future cash flows—comprising coupon payments and principal repayment—assuming no default and reinvestment at the YTM rate.[69][70] YTM solves the equation:P = \sum_{t=1}^{n} \frac{C}{(1 + y)^t} + \frac{F}{(1 + y)^n}

P = \sum_{t=1}^{n} \frac{C}{(1 + y)^t} + \frac{F}{(1 + y)^n}