Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

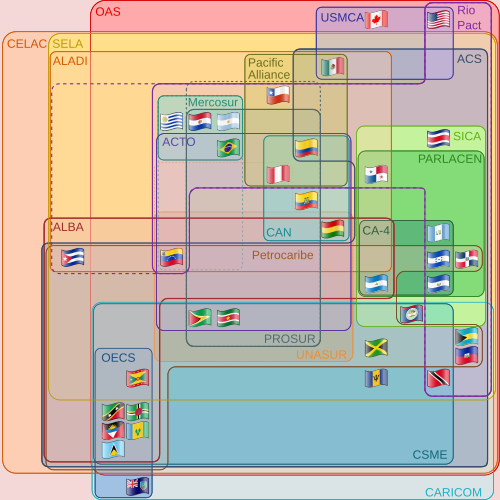

CARICOM Single Market and Economy

View on WikipediaThis article needs to be updated. (January 2013) |

| This article is part of the series on |

| Politics and government of the Caribbean Community |

|---|

|

|

|

The CARICOM Single Market and Economy, also known as the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME), is an integrated development strategy envisioned at the 10th Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) which took place in July 1989 in Grand Anse, Grenada.[1] The Grand Anse Declaration[2] had three key Features:

- Deepening economic integration by advancing beyond a common market towards a Single Market and Economy.

- Widening the membership and thereby expanding the economic mass of the Caribbean Community (e.g. Suriname and Haiti were admitted as full members in 1995 and 2002 respectively).

- Progressive insertion of the region into the global trading and economic system by strengthening trading links with non-traditional partners.

A precursor to CARICOM and its CSME was the Caribbean Free Trade Agreement, formed in 1965 and dissolved in 1973.

Single market and economy

[edit]The CSME will be implemented through a number of phases, first being the CARICOM Single Market (CSM). The CSM was initially implemented on 1 January 2006, with the signing of the document for its implementation by six original member states. However the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas establishing the CSME had been provisionally applied by twelve member states of CARICOM from 4 February 2002, under a Protocol on the Provisional Application of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas.[3] Nine protocols had been drafted to amend the Original Treaty of Chaguaramas and had been consolidated into the Revised Treaty[3] signed at Nassau in 2001,[4] with a number of the Protocols having been applied in part or in full from their creation in 1997-1998 including the provision on the Free Movement of Skilled Nationals.[5]

As of 3 July 2006, it now has 12 members. Although the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME) has been established, in 2006 it was only expected to be fully implemented in 2008.[6] Later in 2007 a new deadline for the coming into effect of the Single Economy was set for 2015,[7] however, following the 2008 financial crisis and the resulting Great Recession, in 2011, CARICOM Heads of Government declared that progress towards the Single Economy had been put on pause.[8] The completion of the CSME with the Single Economy will be achieved with the harmonization of economic policy, and possibly a single currency.[6]

At the eighteenth Inter-Sessional CARICOM Heads of Government Conference in St. Vincent and the Grenadines from 12 to 14 February 2007,[9] it was agreed that while the framework for the Single Economy would be on target for 2008, the recommendations of a report on the CSME for the phased implementation of the Single Economy would be accepted.[10] The Single Economy is now expected to be implemented in two phases.

Phase 1

[edit]Phase 1 was to take place between 2008 and 2009 [10] with the consolidation of the Single Market and the initiation of the Single Economy. Its main elements would include:

- The outline of the Development Vision and the Regional Development Strategy

- The extension of categories of free movement of labour and the streamlining of existing procedures, including contingent rights

- Full implementation of free movement of service providers, with streamlined procedures

- Implementation of Legal status (i.e. legal entrenchment) for the CARICOM Charter for Civil Society

- Establishment and commencement of operations of the Regional Development Fund

- Approval of the CARICOM Investment Regime and CARICOM Financial Services Agreement, to come into effect by 1 January 2009

- Establishment of the Regional Stock Exchange

- Implementation of the provisions the Rose Hall Declaration on Governance and Mature Regionalism, including:

- The automatic application of decisions of the Conference of Heads of Government at the national level in certain defined areas.

- The creation of a CARICOM Commission with Executive Authority in the implementation of decisions in certain defined areas.

- The automatic generation of resources to fund regional institutions.

- The strengthening of the role of the Assembly of Caribbean Community Parliamentarians.

- Further technical work, in collaboration with stakeholders, on regional policy frameworks for energy, agriculture, sustainable tourism, agro-tourism, transport, new export services and small and medium enterprises.

During Phase 1 it is also expected that by 1 January 2009, there would be:

- Negotiation and political approval of the Protocol on Enhanced Monetary Cooperation

- Agreement among Central Banks on common CARICOM currency numeraire

- Detailed technical work on the harmonisation of taxation regimes and fiscal incentives (to commence on 1 January 2009).[11]

Progress and delays

[edit]While progress on the elements of Phase 1 has not resulted in its completion by 2009, a number of its elements have been met, including:

- The outline of the Development Vision and the Regional Development Strategy[11]

- The extension of categories of free movement of labour (to now include to household domestics, nurses, teachers and workers holding specific categories of vocational qualifications) and the streamlining of existing procedures, including contingent rights[12]

- Full implementation of free movement of service providers, with streamlined procedures[13]

- Establishment of the Regional Development Fund and Regional Stock Exchange

Notable elements that have yet to be completed are; legal entrenchment for the CARICOM Charter for Civil Society,[14] approval of the CARICOM Investment Regime and CARICOM Financial Services Agreement (although in August 2013 Finance Ministers of the member states in a Community Council meeting approved the draft CARICOM Financial Services Agreement and the draft amendment to the Intra-CARICOM Double Taxation Agreement),[15] and implementation of the provisions the Rose Hall Declaration on Governance and Mature Regionalism.[16]

Phase 2

[edit]Phase 2 is to take place between 2010 and 2015[10] and consists of the consolidation and completion of the Single Economy. It is expected that decisions taken during Phase 1 would be implemented within this time period, although the details will depend on the technical work, consultations and decisions that would have been taken. Phase 2 will include:

- Harmonisation of taxation systems, incentives and the financial and regulatory environment

- Implementation of common policies in agriculture, energy-related industries, transport, small and medium enterprises, sustainable tourism and agro-tourism

- Implementation of the Regional Competition Policy and Regional Intellectual Property Regime

- Harmonisation of fiscal and monetary policies

- Implementation of a CARICOM Monetary Union.[11]

St. Ann's Declaration

[edit]At the conclusion of a special summit on the CSME held in Trinidad and Tobago from 3–4 December 2018, the leaders agreed to a three-year plan on the CSME. This plan will include:[17]

- Revising the Treaty of Chaguaramas to enable the private sector and labour representatives to have formalized, structured and facilitated dialogue with the Councils of the Community and include representative bodies from the private sector and labour associate institutions of the Community[18]

- Examine the reintroduction of a Single Domestic Space for passengers travelling in the region and introducing a single security check for direct-transit passengers on intra-Community flights making multiple stops[18]

- Deepen cooperation and collaboration between the secretariats of CARICOM and the OECS to avoid duplication of efforts and maximize the use of resources[18]

- Finalize a Community Public Procurement regime by 2019[18]

- Holding indepth discussions on key sectors including region's ICT needs, inter-regional marine and air transport, renewable energy, agriculture, and food security so that by the 40th regular meeting of the CARICOM Heads of Government in July 2019 there will be an understanding of what actions will be required

- Reviewing agricultural and phytosanitary measures, with the objective of removing constraints on inter-regional trade. A report on this review is due in February 2019

- Continuing work on a CARICOM financial services agreement, an investment policy and investment code, with such work to be completed by July 2019

- Taking all necessary steps to create an integrated capital market and model securities legislation by July 2019

- Enabling the mutual recognition of companies and the mutual recognition of CARICOM skills certificates by July 2019 so that individuals and companies can trade or work freely across the CSME

- Bring forward model legislation for trademarks and the harmonisation of business names by July 2019

- The creation of a regional deposit insurance system and credit information sharing system by December 2019

- Introducing a single window for region-wide company registration by December 2019

- Introducing a simple administrative process for the freedom of movement of goods by the end of 2019

- The full integration of Haiti into the CSME in 2020[18]

- Reviewing CARICOM's 17 institutions by early 2020 to ensure they were working effectively and efficiently so that delays would no longer occur

- Harmonizing companies law by the end of 2020

- Introducing a single window for intellectual property registration, patents, and trademarks by the end of 2021

- Total freedom of movement for CARICOM nationals by those states so willing by the end of 2021.

Member states

[edit]

Current twelve full members of both CARICOM and the CSME:

Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda Barbados

Barbados Belize

Belize Dominica

Dominica Grenada

Grenada Guyana

Guyana Jamaica

Jamaica Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Suriname

Suriname Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago

Of the twelve members expected to join the CSME, Barbados, Belize, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago were the first six to implement the CARICOM Single Market on 1 January 2006.[19] Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines were the next batch of members (six in all) that joined the CSM on 3 July 2006 at the recent CARICOM Heads of Government Conference.[20]

Current full members of CARICOM and partial participant of the CSME:

Haiti's Parliament ratified the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas in October 2007 and Haitian Foreign Minister Jean Renald Clerisme presented the published Notice of Ratification to the Chairman of the Caribbean Community Council of Ministers, on 7 February clearing the way for the country's full participation in the CSME[21] on 8 February 2008.[3][22] Haiti has not completed its implementation of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas and is therefore not a full participant in the Single Market and Economy. In keeping with the thrust to rebuild the country following the 2010 earthquake and earlier 2004 political crisis, work has also continued on preparing Haiti to participate effectively in the CSME. It is being assisted in its preparations by the Secretariat, led by the CARICOM Representation Office in Haiti (CROH) which was re-opened in 2007 with funding from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA).[23] The CROH, in 2007 started the Haiti CSME Project, the objective of which was to assist the Government of Haiti in accelerating its participation in the CSME as a means of enabling Haiti to fully re-engage in the process of regional integration in the Caribbean Community.[24]

As a first step towards the CSME, Haiti was due to enter the trade in goods regime of the Single Market in January 2010 (earlier targets had been for some time in 2009)[25] but could not do so because of the earthquake.[23] Up until that point much work had been done by CROH and its Haitian government counterpart, the Bureau de Coordination et de Suivi or BCS (Office of Coordination and Monitoring), on the technical work necessary to bring the Haitian national tariff in line with the Caricom Common External Tariff (CET). The next step that had to be taken for Haiti to commence full free trade in goods within the CSME was therefore for the Haitian Parliament to pass legislation adopting the Caricom External tariff as Haiti's national tariff. In mid 2009, the Government of Haiti announced that it would be ready to participate fully in free trade in goods within the CSME by 1 January 2010; and in fact through a revised Custom Act adopted by the Haitian Parliament in late 2009, 20–30% of the Caricom CET was incorporated into the Haitian national tariff. However soon after Haiti's progress towards full adoption of the CET began to stall with the dismissal of the Government of Prime Minister Michèle Pierre-Louis in November 2009 and was then put on hold as a result of the January 2010 earthquake.[24] To assist in stimulating economic activity, the Council for Trade and Economic Development (COTED) in December, approved a request for some Haitian products to be exported within the Single Market on a non-reciprocal preferential basis for three years. Consultations are on-going towards approval of additional items from an original list which Haiti submitted. The concession became effective from 1 January 2011. CARICOM Secretariat officials are continuing their training exercises with Haitian customs officials to facilitate their understanding of the CSME's trading regime.[23]

In regards to the inclusion of Haitians in the free movement of skilled nationals under the CSME regime and a review of the visa policy towards Haitian nationals by other Caricom states some progress has been made. By early 2009, representation to the Caricom Heads of Government on the issue, particularly arising out of difficulties faced by Government officials travelling to Caricom meetings, led the Conference of Heads of Government to waive visa requirements for Haitian Government officials bearing official Government passports. In 2010 Caricom Heads of Government went a step further to facilitate travel by Haitian businesses persons and agreed that Haitians possessing US and Schengen visas would not require visas to enter other Caricom member states.[24] In regards to participation in the free movement of skilled nationals, Haiti has also been included in the relevant legislation of at least some CSME states as a participating member state.[26]

In 2018 at both a meeting of COTED and at a special summit on the CSME, it was announced that Haiti intends to have in place the necessary legislative and administrative framework for duty free trading in goods by October 2019[27] to enable its full integration into the CSME by 2020.[18]

Current full members of CARICOM and signatory for (and de facto participant of) the CSME:

Montserrat was awaiting entrustment (approval) of the United Kingdom with regards to the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas in order to participate,[28] but such entrustment was denied in mid-2008, and the CARICOM Heads of Government (including Montserrat) expressed disappointment and urged the United Kingdom to reconsider its position.[29] Until such time, Montserrat remains a member under the conditions existing immediately prior to the coming into force of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas and the CSM on 1 January 2006 and as such is legally in a common market relationship with all CSM participating states.[30] This means that while goods from Montserrat are eligible for CARICOM treatment and free trade (as covered under the old Common Market Annex), service providers in Montserrat are not eligible for CARICOM treatment unless so provided for by the various CSM countries individually in legislation or administratively.[31]

Since the start of the CSME process and after the denial of entrustment, Montserrat has been treated in the relevant legislation of other member states as being a participant of the CSME[26][32][33] and Montserrat itself implements aspects of the CSME where possible for its own residents[34] and for nationals of other CSME states[35] (or provides more favourable treatment for such nationals where full implementation is not possible).[36] These measures include legal provisions for the automatic grant of 6 months stay under the freedom of movement obligations and honouring CARICOM skills certificates in Montserrat[37] (the latter measure the Government of Montserrat had been implemented by way of amendments to existing Statutory Rules and Orders since 1996 in keeping with conformity with the original Conference of Heads of Government decision on the free movement of university graduates).[38] Montserrat also issues land holding licenses to CARICOM nationals as an administrative procedure in seeking to comply with CARICOM's right of establishment obligations, and intends to remove all impediments except for those related to cost recovery. Montserrat's compliance with the movement of capital obligations under the CSME is already assured within the framework of the East Caribbean Currency Union.[37]

At the thirty-fifth regular meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government ending on 4 July 2014, Reuben Meade, Premier of Montserrat, announced that Montserrat intends to accede to the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas by the next meeting of the Conference, paving the way for its full participation in the Community and particularly the CSME. Montserrat has been progressively making steps towards accession to the Revised Treaty, including obtaining the necessary instrument of entrustment from the United Kingdom. To this end Montserrat will be engaging with the CARICOM Secretariat and relevant CARICOM Institutions and the Caribbean Court of Justice in preparation for the deposit of its Instrument of Accession at the Twenty-Sixth Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference, to be held in February 2015 in The Bahamas.[39]

Following the September 2014 general elections in Montserrat, Reuben Meade's government was replaced by new government led by Donaldson Romeo. Romeo's government remained committed to acceding to the Revised Treaty, although the target date of February 2015 was not achieved. In July 2015, at the 36th Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government in Bridgetown, Barbados, Romeo gave assurances that Montserrat was continuing efforts to complete the process of accession to the Revised Treaty in a timely manner. He revealed that engagement continued with the government of the United Kingdom and that the necessary legislation was being prepared for submission to the Legislative Assembly of Montserrat. He also stated that Montserrat viewed accession to the Caricom Development Fund and to the original jurisdiction of the Caribbean Court of Justice as being necessary to move Montserrat forwards in its effort to integrated and to safeguard the rules upon which its trade was based.[40]

Current full members of CARICOM but not the CSME:

Current 5 associate members of CARICOM but not the CSME:

British Virgin Islands (July 1991)

British Virgin Islands (July 1991) Turks and Caicos Islands (July 1991)

Turks and Caicos Islands (July 1991) Anguilla (July 1999)

Anguilla (July 1999) Cayman Islands (15 May 2002)

Cayman Islands (15 May 2002) Bermuda (2 July 2003)

Bermuda (2 July 2003)

Current 7 observing members of CARICOM but not the CSME:

Caribbean Court of Justice

[edit]The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) is the Highest regional Court established by the Agreement Establishing in the Caribbean Court of Justice. It has a long gestation period commencing in 1970 when the Jamaican delegation at the Sixth Heads of Government Conference, which convened in Jamaica, proposed the establishment of a Caribbean Court of Appeal in substitution for the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

The Caribbean Court of Justice has been designed to be more than a court of last resort for Member States of the Caribbean Community of the Privy Council, the CCJ was vested with an original jurisdiction in respect of the interpretation and application of the Treaty Establishing the Caribbean Community (Treaty of Chaguramas) In effect, the CCJ would exercise both an appellate and an original jurisdiction.

In the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction, the CCJ considers and determines appeals in both civil and criminal matters from common law courts within the jurisdiction of Member States of the Community and which are parties to the Agreement Establishing the CCJ. In the discharge of its appellate jurisdiction, the CCJ is the highest municipal court in the Region. In the exercise of its original jurisdiction, the CCJ will be discharging the functions of an international tribunal applying rules of international law in respect of the interpretation and application of the Treaty and so will be the court of arbitration for trade disputes under the CSME.

By 2006, only two countries were full signatories to the Court: Barbados and Guyana, it was expected that by the end of 2010, all 14 member countries would be fully involved. However, only Belize acceded to the appellate jurisdiction in 2010 while all other states were in various stages of moving towards full accession to the court's appellate jurisdiction. Dominica thereafter acceded to the appellate jurisdiction in March 2015.

(Source; CARICOM's official website at[41])

Trade in goods

[edit]All goods which meet the CARICOM rules of origin are traded duty-free throughout the region (except The Bahamas), therefore all goods originating within the region can be traded without restrictions. In addition, most member states apply a Common External Tariff (CET) on good originating from non-CARICOM countries. There are, however, some areas still to be developed:

- Treatment of products made in Free Zones – there is need for regional agreement on how these goods are to be treated since they are usually manufactured at reduced tariff by foreign companies.

- The removal of some specific non-tariff barriers in various member-states.

Another key element in relations to goods is Free Circulation. This provision allows for the free movement of goods imported from extra regional sources which would require collection of taxes at first point of entry into the CSME and for the sharing of collected customs revenue.

(Sources; JIS website on the CSME at[42] and CARICOM website on the CSME at[43])

Harmonization of standards

[edit]Complementary to the free movement of goods will be the guarantee of acceptable standards of these goods and services. To accomplish this, CARICOM members have established the Caribbean Regional Organization on Standards and Quality (CROSQ). The Organization will be responsible for establishing regional standards in the manufacture and trade of goods which all Member States must adhere to. This Organization was established by a separate agreement from the CSME.[42]

As an example of the work of the CROSQ, in conjunction with other regional bodies, on 6 October 2017, COTED approved nine poultry processing plants in Barbados, Belize[44] (including Quality Poultry Products' plant and Caribbean Chicken's plant),[45][46] Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago to trade poultry and poultry products across the region after assessments by Regional Risk Assessment Teams (coordinated by the Caribbean Agricultural Health and Food Safety Agency (CAHFSA) and reviewed and finalized by the CARICOM Committee of Chief Veterinary Officers) proved they met the sanitary requirements (Specifications for Poultry and Poultry Products) developed by CROSQ and approved by COTED in 2013. Additionally the COTED resolved the disagreement on duck meat trade between Trinidad and Tobago and Suriname, with Trinidad and Tobago now willing (by mid-November 2017) to approve Suriname as one of the countries that has met the sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) requirements for exporting duck meat to the country.[44]

Regional accreditation

[edit]Regional accreditation bodies are planned to assess qualifications for equivalency, complementary to the free movement of persons. To this end, the Member States have concluded the Agreement on Accreditation for Education in Medical and other Health Professions. By this agreement, an Authority (the Caribbean Accreditation Authority for Education in Medicine and other Health Professions) is established which will be responsible for accrediting doctors and other health care personnel throughout the CSME. The Authority will be headquartered in Jamaica, which is one of among six states (Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Jamaica, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago) in which agreement is already in force. The Bahamas has also signed on to the Agreement.

Region-wide accreditation has also been planned for vocational skills. Currently local training agencies award National Vocational Qualifications (NVQ)[47] or national Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) certification,[48] which are not valid across Member States. However, in 2003, the Caribbean Association of National Agencies (CANTA) was formed as an umbrella organization of the various local training agencies including Trinidad and Tobago's National Training Agency, the Barbados TVET Council and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States TVET agency and the HEART Trust/NTA of Jamaica. Since 2005, the member organizations of CANTA have been working together to ensure a uniformed level of certified skilled labour under the Caricom Single Market and Economy (CSME) and CANTA itself has established a regional certification scheme that awards the Caribbean Vocational Qualification (CVQ),[48] which is to replace NVQs and national TVET certifications.[47] The CVQ will be school-based and although based on the certification scheme of CANTA, will be awarded by the Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC) which will be collaborating with CANTA on the CVQ programme.[49] At the 9–10 February 2007 meeting of the Regional Coordinating Mechanism for Technical and Vocational Education and Training, officials discussed arrangements for the award of the CVQ which was approved by the Council for Human and Social Development (COHSOD) in October 2006.[50] It was expected that the CVQ programme may be in place by mid-2007, if all the requirements are met[10][51] and that provisions were being made for the holders of current NVQs to have them converted into the regionally accepted type (although no clear mandate is yet in place).[51] This deadline was met and in October 2007, the CVQ programme was officially launched. The CVQ now facilitates the movement of artisans and other skilled persons in the CSME. This qualification will be accessible to persons already in the workforce as well as students in secondary schools across the Caribbean region. Those already in the work force will be required to attend designated centres for assessment.[52]

The CVQ is based on a competency-based approach to training, assessment and certification. Candidates are expected to demonstrate competence in attaining occupational standards developed by practitioners, industry experts and employers. Those standards when approved by CARICOM allow for portability across the Region. Currently, CVQs are planned to reflect a Qualification framework of five levels. These are:

- Level 1: Directly Supervised/Entry –Level Worker

- Level 2: Supervised Skilled Worker

- Level 3: Independent or Autonomous Skilled Worker

- Level 4: Specialized or Supervisory Worker

- Level 5: Managerial and/or Professional Worker[53]

CVQ's are awarded to those candidates who would have met the required standards in all of the prescribed units of study. Statements are issued in cases where candidates did not complete all the requirements for the award of CVQ. Schools that are suitably equipped currently offer Levels 1 & 2.[53]

By March 2012 up to 2,263 CVQs had been awarded in the workforce across the region and 2,872 had been awarded in schools for a total of 5,135 CVQs awarded up to that time. The breakdown of the agency awarding the over 5,000 CVQs by March 2012 stood at 1,680 having been awarded by the CXC and 3,455 being awarded by the various National Training Agencies (with some being awarded in the workplace and some being awarded in secondary schools).[54]

(Main Sources; JIS website on the CSME and Google Cache of SICE - Establishment of the CSME at[55] - see references)

Abolition of work permits/permits of stay and the free movement of persons

[edit]Chapter III of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas provides for the free movement of skilled Community nationals (article 46) as well as for the free movement of non-wage earners, either as service providers and/or to establish businesses, including managerial, supervisory and technical staff, and their spouses and immediate family members.[56]

Trade in services and the right of establishment

[edit]Along with the free trade in goods, the Revised Treaty also provides the framework for the establishment of a regime for free trade in services. The main objective is to facilitate trade and investment in the services sectors of CSME Member States through the establishment of economic enterprises. The free trade regime for services grants the following benefits:

| Benefit | Description |

|---|---|

| The Right of Establishment | CARICOM-owned companies will have the right to establish and operate businesses in any CSME member-state under the same terms and conditions as local companies, i.e. without restrictions. Managerial, technical and supervisory staff of these enterprises will be able to enter and work without work permits. |

| Region-wide Services | CARICOM service providers will be able to offer their services throughout the region, again without work permits, usually on a temporary basis, e.g., consultancies. |

Right of establishment

[edit]The right to work as a self-employed person has been provided for in respect of persons wishing to engage in non-wage earning activities of a commercial, industrial, agricultural or artisanal nature.[57] Non-Wage Earners are self-employed CARICOM Nationals (juridical as well as natural persons) who have the right to work as self-employed persons in the C.S.M.E. and these persons can move to another Member State to establish a business or to provide a service on temporary basis.[58]

Such nationals may create and manage economic enterprises, including any type of organization which they own or control (e.g. sole proprietorship, company, etc.) for the production of or trade in goods, or the provision of services.[57] Service providers may also move to establish businesses under the Companies Act or the Registration of Business Names Act. The procedure in those cases would be the same as those applying to the establishment of business for the provision of goods by a Company.[59] Nationals exercising this right may move to another Member State on a permanent basis.[57] This category of person is not required to obtain a Free Movement of Skill Certificate, however Service Providers must obtain a Certificate of Registration as a CARICOM Service Provider.[58]

Affiliated with the right of establishment is the right to move the Technical, Supervisory and Managerial staff of such entities, as well as their spouses and immediate dependent family members. Persons within any of these five (5) named classes are not allowed to move in their own right unless they fall under one of the nine (9) approved categories (where the member state recognizes these categories).[57]

Several procedures have been approved for treatment of persons wishing to establish business enterprises in other member states. These involve:[57]

- Procedures at Point of Entry whereby Immigration must grant a definite stay of six (6) months, upon the national presenting a valid passport, return ticket and proof of financial resources for personal maintenance.

- Procedures post-entry. This includes the requirement for a migrant CARICOM National to apply to the Competent Authority (usually the Registrar of Companies) of the receiving state, for registration of a business enterprise.

Entry procedure at point of entry for right of establishment

[edit]CARICOM Nationals specifically wishing to move from one Member State to another in exercising the right of establishment will have to present the following at point of entry:[60]

- (i) Valid passport;

- (ii) Return ticket;

- (iii) Proof of financial resources for personal maintenance, namely credit cards, travellers cheques, cash or combination thereof.

Immigration will then grant the CARICOM National a definite stay of 6 months.[60]

Procedure after entry for right of establishment

[edit]Each Member State shall designate a Competent Authority for Right of Establishment. After entry has been granted the CARICOM National must submit to the Competent Authority, relevant proof, such as Police Certificate, Financial Resources, Business Names Certificate / Certificate of Incorporation. The Competent Authority will determine if all requirements to establish the particular business have been satisfied. Once all requirements are satisfied, the Competent Authority will issue a letter of approval to the CARICOM national copied to the Immigration Department. If the business is established within the 6 months period then the CARICOM National must report to the Immigration Department to further regularize his / her stay with the Letter of Approval from the Competent Authority. Immigration will grant the CARICOM National an indefinite stay.[60]

Member States will determine through the national mechanisms which have been established for that purpose, whether the business is operational. If the CARICOM National is no longer operating the business or another business the Competent Authority for Rights of Establishment will inform the Immigration Department, which has the right to rescind the indefinite stay or to indicate to the person that he / she needs to apply for a permit of stay and / or a work permit until such time that there is full free movement in the Community.[60]

Extension for right of establishment

[edit]In the event that the business is not established within the 6-month period, the CARICOM National should present to the Immigration Department or other relevant department so designated by the Member State, evidence from the Competent Authority that concrete steps have been undertaken to establish the business. Where such evidence is provided, the CARICOM National will be granted an extension of 6 months.[60]

Stamps for right of establishment

[edit]There are specific stamps for the definite entry of 6 months, the extension of 6 months and the indefinite stay with the following text – [60]

- (i) Right of Establishment – Definite Entry of 6 Months;

- (ii) Right of Establishment – Extension; and

- (iii) Right of Establishment – Indefinite Entry.

A CARICOM national whose passport is stamped with one of the above is automatically entitled to multiple entry into that Member State.[60]

Integrated online registry

[edit]From 8–10 December 2014, a meeting by Registrars of Companies from the 12 participating CSME member states was held to discuss the development of a complete online registry. The meeting was held in Saint Lucia and was convened by CARICOM Secretariat and funded by the European Union under the 10th European Development Fund (EDF) as part of the CSME and Economic Integration Programme.[61]

The Registrars of Companies across the region held the meeting to consider the proposal for the harmonization of online registries in the CSME participating Member States. This harmonization would be facilitated by the web interface and interoperability of the respective systems allowing users access to information from participating Member States. The objective of the initiative is for interested parties to be able to register businesses/companies online across Member States thereby increasing cross-border economic activity. The other issues that are down for discussion are the software and hardware requirements of the systems to be installed as well as training for data entry operators and other relevant users in the registries.[61]

The beneficiary Member States under the project are Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago. Alfa XP Europe Limited is the company undertaking the consultancy.[61]

Temporary provision of services

[edit]While service providers may establish businesses under the right of establishment they may, however, make their services available in other member states using another mode, that is, by moving on a temporary basis.[59] CARICOM Nationals who wish to move from one CARICOM Member State to another in order to provide such services on a temporary basis are required to register as a service provider in the Member State, where he/she is living and working in order to be issued with a certificate, which will facilitate the entry into another Member State.[60] As with the establishment of businesses, there are approved procedures both at points of entry and after entry, regarding treatment of CARICOM nationals wishing to temporarily provide services.[59]

Critical to this process is the application for and the issuance of a certificate by the Competent Authority within the national's country, subject to the provision of proof relating to:[59]

- (a) CARICOM nationality; and

- (b) competency to provide the service, or contract to offer service or letter from relevant association or reputable person or body.

The certificate, the lifetime of which is indefinite, along with a valid passport and the contract to offer service or an invitation letter, must be presented to the Immigration officer at the port of entry, who should then grant the CARICOM National sufficient time to provide the service. A regime has also been approved in respect of the granting of extensions under this regime.[59]

Entry procedure at point of entry for provision of temporary services

[edit]CARICOM Nationals specifically wishing to move from one Member State to another to provide services on a temporary basis must present their certificate of registration as a CARICOM service provider at the point of entry to the Immigration Officer as proof that the CARICOM National is a service provider who is seeking to enter to provide services on a temporary basis.[60] Other documents required are - [60]

- (i) a valid passport;

- (ii) contract to offer service or invitation letter from a client.

The Immigration Officer will grant the CARICOM National sufficient time to provide the service.[60]

Procedure for the automatic extension of the stay for provision of temporary services

[edit]In cases where the temporary service is not completed within the stipulated time period, an automatic extension must be requested from the Immigration Department. The automatic extension will be granted in order to enable the CARICOM National to complete the service once the service provider submits proof that the service is not yet completed.[60]

The automatic extension is based on rights enshrined in the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, namely non-discrimination (national treatment) and the right to provide a service through mode 4 – the movement of national persons.[60]

The process to extend the stay should not take longer than ten working days.[60]

(Main Source; JIS website on the CSME - see references)

Abolition of work permits and the free movement of labour

[edit]The Free Movement of Skilled Persons, arises from an agreed CARICOM policy that was originally separate but related to the original Protocol II of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas.[62] The agreed policy, called The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Free Movement of Persons Act, is now enacted legislation in all the CSME Member States. It provides for the free movement of certain categories of skilled labour, but according to the policy there is to be eventual free movement of all persons, originally by 2008, but now by 2009.[10] Under this legislation, persons within these categories can qualify for Skills Certificates (which allow for the free movement across the region).

Since the start of the CSM, eight categories of CARICOM nationals have been eligible for free movement throughout the CSME without the need for work permits. They are: University Graduates, Media Workers, Artistes, Musicians, Sportspersons, Managers, Technical and Supervisory Staff attached to a company and Self-Employed Persons/Service Providers.[63] In addition the spouses and immediate dependent family members of these nationals will also be exempt from work permit requirements. At the July 2006 CARICOM Summit, it was agreed to allow for free movement of two more categories of skilled persons; tertiary-trained Teachers and Nurses. It was also agreed that higglers, artisans, domestic workers and hospitality workers are to be added to the categories of labour allowed free movement at a later date, pending the agreement of an appropriate certification.[64] This envisioned extension for the latter categories of workers such as artisans was achieved in October 2007 with the launch of the Caribbean Vocational Qualification (CVQ).[52] In 2009 Antigua and Barbuda and Belize were permitted to delay extending free movement to domestic workers until a study was conducted on the impact on their countries on the free movement of this new category of worker. Antigua and Barbuda was also granted an outright five-year exemption to the extension of free movement to domestic workers (to go with its existing exemption from the free movement of non-graduate teachers and nurses) in order for it to make the necessary adjustments to its infrastructure and other imperatives to facilitate the fulfillment its obligations and in recognition of the fact that Antigua and Barbuda had always implement a very liberal immigration policy granting admission beyond the approved categories eligible for free movement which resulted in a high population of persons from other Member States.[65][66] In 2015 Antigua and Barbuda was seeking the continuation of this exemption on domestic workers for a further 5 years,[66] and was granted a 3-year extension to this exemption in 2015.[67] Following on from a special summit on the CSME in early December 2018, held in Trinidad and Tobago, the Heads of Government agreed to expand the categories of skilled nationals eligible for free movement to include security guards, beauticians/beauty service practitioners, agricultural workers and barbers. They further agreed that those member states willing to do so, should move ahead to full freedom of movement within the next three years.[18] At the 30th Inter-Sessional Conference of the Heads of Government in February 2019, Antigua and Barbuda and St. Kitts and Nevis sought and were granted a five-year deferral on permitting the free movement of security guards, beauticians/beauty service practitioners, barbers, and agricultural workers under the free movement of skills regime.[68]

The freedom to live and work throughout the CSME is granted by the Certificate of Recognition of CARICOM Skills Qualification (commonly called a CARICOM Skills Certificate or just a Skills Certificate). The Skills Certificate essentially replaces work permits and are obtained from the requisite ministry once all the essential documents/qualifications (which varies with each category of skilled persons) are handed in with an application. The issuing ministry varies depending upon the CARICOM Member State. In Antigua and Barbuda, Jamaica and Suriname the Skills Certificates are issued by the Ministry of Labour. Grenada, Guyana, St. Lucia and Trinidad and Tobago have Ministries for Caribbean Community Affairs which deal with the Certificates. Meanwhile, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, St. Kitts and Nevis and St. Vincent and the Grenadines issue the Certificates through the Ministries of Immigration. The Skills Certificate can be applied for in either the home or host country.[69]

At the eighteenth Inter-Sessional CARICOM Heads of Government Conference in February, it was agreed that artisans would not be immediately granted free movement status from January (as was originally envisaged), but would rather be granted free movement by mid-2007. The free movement of artisans will be facilitated through the award of Caribbean Vocational Qualifications (CVQ) based on industrial occupational standards. The conference also agreed that the free movement of domestic workers and hospitality workers could be facilitated in a similar manner to the free movement of artisans and that their cases would be considered after the CVQ model is launched.[10] The CVQ itself was launched in October 2007, thereby facilitating the free movement of these categories of workers.[52]

The Free Movement of Labour is also being facilitated by measures to harmonize social services (health, education, etc.) and providing for the transfer of social security benefits (with the Bahamas also being involved). Regional accreditation will also facilitate the free movement of people/labour.

Although the CARICOM Skills Certificate regime pre-dates the formal inauguration of the CSME (Skills Certificates have been available since 1997, while the CSME was only formally instituted in 2005 following provisional application of the CSME protocols in 2001) the number of Skills Certificates issued to qualifying CARICOM nationals has only really taken off since the CSME was instituted.[70] Between 1997 and 2005 only nine Member States had issued certificates of Recognition of Skills on a relatively small scale. Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica and Guyana have issued the bulk of these certificates.[71] By September 2010 approximately 10,000 Skills Certificates had been issued by the 12 member states[72] with the available data on free movement indicating that more than 6,000 of these skills certificates having been issued between 2006 and 2008.[70] At an address to the graduates of the 48th Convocation of the University of Guyana on 8 November 2014, CARICOM's Secretary General, Irwin La Rocque, revealed that up to November 2014 a total of 14,000 Skills Certificates had been issued and he urged the graduates to apply for their own Skills Certificates now that they were eligible.[73]

Individually, some countries account for a large percentage of the total Skills Certificates issued. For instance between 1997 and July 2010, Guyana had issued 2,829 skills certificates.[74] Up to June 2011, Jamaica had issued 2,113 skills certificates.[75] And as of September 2013, Jamaica had issued 2,893 skills certificates. Data also indicated that the number of verifications and the number of certificates issued by other member states to Jamaicans for 2004 to 2010 amounted to 1,020.[76] And between 2001 and 2006 Trinidad and Tobago issued 789 Skills Certificates.[77][78] By 2008, Trinidad and Tobago had issued a total of 1,685 Skills Certificates.[79]

A survey conducted in 2010, found that between 1997 and June 2010 at least an estimated 4,000 persons had moved under the free movement of skills regime. Specialist Movement of Skills/Labour within the CSME Unit, Steven Mc Andrew said “The study proved that persistent fears in member states that they are being flooded under the free movement regime are clearly unfounded.” He added that another key conclusion was that “free movement has not impacted negatively on the social services in member states. On the contrary it helped to fill critical vacancies in member states with respect to teachers and nurses, thus proving to be very beneficial to maintain a certain level of social services in these countries.”[80]

It is expected that by June 2014, all CARICOM nationals will have easier access to participating CSME Member States, and be able to fully exercise their rights to travel, work and seek out other opportunities as provided for under the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) arrangement.[81]

This is being facilitated through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA)-funded CARICOM Trade and Competitiveness Project (CTCP), under which a critical electronic database is being established. It will, among other things, provide member countries with aggregated information on the various skill sets available, through a web-based portal being developed by project consultant, A-Z Information Jamaica Limited.[81]

Additionally, the consultant is proposing that the CARICOM National Skills Certificate be standardised across countries, and presented in the form of a stamp in persons’ passports. This will eliminate the discrepancies in the format of certificates, as well as the need for a physical document and result in ease of processing at the various points of entry across member countries.[81]

Concurrent with (and to some extent pre-dating) the free movement of people is the easier facilitation of intra-regional travel. This aim is being accomplished by the use of separate Lines identified for CARICOM and Non-CARICOM Nationals at Ports of entry (already in place for all 13 members) and the introduction of a CARICOM Passport and Standardized Entry/Departure Forms.

Contingent Rights accompanying the free movement of skills

[edit]In addition to the right to move freely for the purposes of labour, it was intended that those persons exercising such rights would be able to have their spouses, children and other dependent accompany them and partake in complementary rights such as the right to access primary education, healthcare, transfer capital, access land and other property, work without needing a work permit and leave and re-enter the host country. Work on this Protocol on Contingent Rights started in 2008.[82] The Protocol was finally ready for signature in 2018 and was signed initially by seven member states (Barbados, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Suriname) at the 39th Regular Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of CARICOM held in Montego Bay, Jamaica.[83][84][85] Trinidad and Tobago additionally signed on to the Protocol and the accompanying Provisional Application at a special summit on the CSME in early December 2018, held in Trinidad and Tobago.[86] At the 30th Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads ofg Government from 26 to 27 February 2019 in St. Kitts, all remaining CARICOM Member States participating in the CSME signed up to the Contingent Rights Protocol. Eight of these twelve countries, namely Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, St Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines and Trinidad and Tobago also decided to apply the protocols measures provisionally.[87] In late February and early March, Barbados became the first of the Member States to amend its legislation to give effect to the Protocol.[88]

Free Movement for All People - CARICOM Decision

[edit]The 45th Meeting of the Conference of the Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) was held in July 2023, marking a significant milestone for regional integration in the Caribbean. A crucial outcome of this historic meeting, which coincided with CARICOM's 50th-anniversary celebration, was the agreement on free movement for all CARICOM nationals by March 2024.[89]

This groundbreaking decision extends beyond the current CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) scheme, which allowed free movement only for agreed categories of skilled nationals. This new development was announced by CARICOM Chair, the Hon Roosevelt Skerrit, Prime Minister of Dominica, during the concluding press conference.[89]

According to Prime Minister Skerrit, this change forms a fundamental part of the integration architecture and underpins the core idea of the regional integration movement - the ability for people to move freely within the Caribbean Community. Although he acknowledged potential legal challenges in implementing this policy, a dedicated legal team was appointed to examine these issues and present a definitive position by March 2024.[89]

The announcement was received with enthusiasm, with Prime Minister Skerrit expressing his belief that the founding fathers of the organization would be "smiling from heaven" at this bold decision. He highlighted that in addition to the free movement, certain rights will be accorded, such as access to primary and emergency healthcare, education, and hassle-free travel.[89]

Prime Minister of Barbados, the Hon. Mia Mottley, who holds responsibility for the CSME in the CARICOM Quasi Cabinet, emphasized the need for careful execution. She mentioned the need for treaty amendments to ensure countries are not liable to lawsuits concerning these rights. A minimum set of rights will be discussed, agreed upon, and included in the treaty amendments.[89]

To finance these changes, CARICOM Heads are considering leveraging the CARICOM Development Fund to ensure each member state can bring its minimum level of service up to an acceptable standard. Prime Minister Mottley stated this decision represents the long-held desire of every Caribbean citizen for greater control over their destiny.[89]

However, an exception has been made for Haiti, which has requested a derogation from the free movement agreement due to specific circumstances faced by the member state. Despite this exception, the decision made at this historic conference signifies a significant step towards enhanced regional integration within the Caribbean Community.[89]

Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Heads of Government met in Grenada in July 2024, for the 47th Regular Meeting of the Conference.[90][91]

During the 49th Regular Meeting of the CARICOM Conference of Heads of Government, Jamaican Prime Minister and Chairman of CARICOM Andrew Holness announced the date of commencement for the freedom of movement would be 1 October 2025. The initial four countries expected to implement it are Barbados, Belize, St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Dominica. Holness also added that Jamaica was "remains committed to the goal of full free movement" stating that the reason for the delay was due to "legislative framework and other considerations". It was also stated that the four countries were expected to serve as an experiment in how to implement free movement for the rest of CARICOM.[92]

Nationality criteria

[edit]In relation to a number of issues such as professional services, residency and land ownership, legislation in the various member states used to discriminate in favour of their individual nationals. This legislation has been amended, as of 2005, to remove the discriminatory provisions. This will allow CARICOM nationals, for example, to be eligible for registration in their respective professions on an equal basis.

However, shortly before signing onto the CSM, the second batch of member states (all in the OECS) negotiated an opt-out agreement with regards to land ownership by non-nationals. As the OECS members of the CSM are all small countries and have limited available land, they are allowed to keep their Alien Land Holding Laws or Alien Landholders Acts (which apply to the ownership of land by non-nationals), but will put in place mechanisms to ensure compliance with the Revised Treaty that will monitor the granting of access to land and the conditions of such access.[93] As it now stands foreign companies or nationals have to seek legal permission to buy land.[94] All other laws relating to discrimination in favour of member state nationals only have been amended though. Among the non-OECS members of the CSM, there are no restrictions on private land ownership by CARICOM nationals (although in Suriname, and possibly in the other members as well, restrictions still apply with regards to state-owned land[95]).

(Main Source; JIS website on the CSME - see references)

Harmonization of legislation

[edit]The Revised Treaty also calls for harmonized regimes in a number of areas: Anti-dumping and countervailing measures, Banking and securities, Commercial arbitration, Competition policy, Consumer protection, Customs, Intellectual property rights, Regulation and labelling of food and drugs, Sanitary and phytosanitary measures, Standards and technical regulations & Subsidies.

Draft model legislation is being developed by a CARICOM Legislative Drafting Facility in collaboration with the Chief Parliamentary Counsels of the region

(Main Source; JIS website on the CSME - see references)

Free movement of capital

[edit]The free movement of capital involves the elimination of the various restrictions such as foreign exchange controls and allowing for the convertibility of currencies (already in effect) or a single currency and capital market integration via a regional stock exchange. The member states have also signed and ratified an Intra-Regional Double Taxation Agreement.

Following the conclusion of the 61st CARICOM Committee of Central Bank Governors Meeting on November 3, 2023, The regional central bank governors supported the advancement of work on the pilot of an intraregional payments system called the CARICOM Payments and Settlements System (CAPSS).[96] CAPSS would facilitate the full integration of the various national markets in CARICOM into a single, unified, open market and allow for the smooth and easy flow of capital.[97] The system would develop in partnership with the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank)[97] and would be underpinned by the technology used in the Pan-African Payments & Settlement System of that bank.[98]

At the end of October, at the AfriCaribbean Trade and Investment Forum in Guyana, the President and Chairman of the Afreximbank, Professor Benedict Oramah, had announced the initial partnership and that a payments and settlement programme with an African bank had been selected to run the pilot programme for the CARICOM central banks. He also stated his hopes that soon the payments systems for Africa and CARICOM will be integrated and that he had addressed CARICOM leaders earlier on the year about assisting in the establishment of a CARICOM Import-Export Bank, of which Afreximbank would be a shareholder if so invited.[97][98]

At the same meeting on November 3, the regional central bank governors endorsed a proposal for the establishment of a Regional Central Bank Group of Reserves Managers, that would meet virtually and share experiences and approaches in the management of national foreign exchange reserves.[96][97][98]

Single currency

[edit]Although not expected until between 2010 and 2015,[11] it is intended that the CSME will have a single currency. As it stands a number of the CSME members are already in a currency union with the Eastern Caribbean dollar and the strength of most regional currencies (with the exception of Jamaica's and Guyana's) should make any future exchange-rate harmonization between CSME members fairly straightforward as a step towards a monetary union.

The aim of forming a CARICOM monetary union is not new. As a precursor to this idea the various CARICOM countries established a compensation procedure to favour the use of the member states currencies. The procedure was aimed at ensuring monetary stability and promoting trade development. This monetary compensation scheme was at first bilateral, but this system was limited and unwieldy because each member state had to have a separate account for each of its CARICOM trade partners and the accounts had to be individually balanced at the end of each credit period. The system became multilateral in 1977 and was called the CARICOM Multilateral Clearing Facility (CMCF). The CMCF was supposed to favour the use of internal CARICOM currencies for transaction settlement and to promote banking cooperation and monetary cooperation between member states. Each country was allowed a fixed credit line and initially the CMCF was successful enough that both the total credit line and the credit period were extended by 1982. However, the CMCF failed shortly thereafter in the early 1980s due to Guyana's inability to settle its debts and Barbados being unable to grant new payment terms[99]

Despite the failure of the CMCF, in 1992 the CARICOM Heads of Government determined that CARICOM should move towards monetary integration and commissioned their central bankers to study the possible creation of a monetary union among CARICOM countries. It was argued that monetary integration would provide benefits such as exchange rate and price stability and reduced transaction costs in regional trade. It was also thought that these benefits in turn would stimulate capital flows, intra-regional trade and investment, improve balance of payments performance and increase growth and employment.

The Central Bank Governors produced a report in March 1992 that outlined the necessary steps and criteria for a monetary union by 2000. The 1992 criteria were amended in 1996 and were known as the 3-12-36-15 criteria. They required that:

- countries maintain foreign reserves equivalent to 3 months of import cover or 80% of central bank current liabilities (whichever was greater) for 12 months;

- the exchange rate be maintained at a fixed rate to the US dollar (for Fixers) or within a band of 1.5% on either side of parity (for Floaters) for 36 consecutive months without external debt payment arrears and;

- the debt service ratio to be maintained within 15% of the export of goods and services.

The report envisioned the fulfilment of a monetary union in 3 phases on the basis of grouping the member states into 2 categories, A and B. Category A included the Bahamas, Belize and OECS states. Category A countries had already met the original criteria in 1992 and only had to maintain economic stability to begin the monetary union. Category B consisted of Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago (Suriname and Haiti were not yet members and so were not included). These countries had to make the necessary adjustments to meet the entry criteria.

Phase 1 of the monetary union process was scheduled to conclude in 1996. It was to include the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, the OECS states and Trinidad and Tobago and there was to have been a common currency as a unit of account (cf. the Euro from 1999 to 2002) amongst these states with the exception of the Bahamas and Belize. This phase would also involve the coordination of monetary policies and the movement towards intra-regional currency convertibility among all member states. Phase 1 would also have seen the formation of a Council of CARICOM Central Bank Governors to oversee the entire process.

Phase 2 was to have occurred between 1997 and 2000 and should have seen a number of initiatives:

- the formation of a Caribbean Monetary Authority (CMA), which would be accountable to a Council of Ministers of Finance.[100]

- the issuance and circulation of a physical common currency in all Phase 1 countries except the Bahamas.

- the use of the new currency in the other countries (the Bahamas, Guyana and Jamaica) as a unit of account in settling regional transactions.

- the continued efforts by Guyana and Jamaica to meet the criteria for entry into the monetary union if they had not already done so and achieved economic stability.

Phase 3 was planned to begin in 2000 and had as its ultimate goal to have all CARICOM countries entering into the monetary union and membership of the CMA.

However, the implementation of Phase 1 was put on hold in 1993 as a result of Trinidad and Tobago floating its dollar. In response and in an effort to continue pursuing monetary cooperation and integration, CARICOM Central Bank Governors made their regional currencies fully inter-convertible. A subsequent proposal called for Barbados, Belize and the OECS states to form a currency union by 1997 but this also failed.[101]

Development fund

[edit]One of the institutions and regimes created to give life to the regional integration movement through the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, is the CARICOM Development Fund (CDF). It forms a critical part of the community's aim for equitable engagement among its member states. The idea for the CDF was borrowed substantially from a similar mechanism successfully employed the European Union[102] (the EU's Cohesion Fund)[103] in helping bring certain of its member states, such as Ireland, up to a certain economic level to assist them in effectively participating and benefiting from the integration process.[102]

The CDF was established under Article 158 of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas “for the purpose of providing financial or technical assistance to disadvantaged countries, regions and sectors.” It is the centre-piece of a regime to address the disparities among the Member States of the Community which may result from the implementation of the CSME. The signing of the Agreement Relating to the Operations of the Fund in July 2008, followed years of negotiations by CARICOM Member States regarding the principles, size and structure of a regional development fund.[102]

There was a sense of achievement when the agreement was finally signed and technicians employed by the CDF got down to the task of making the mechanism operational. In an interview, CDF Chief Executive Officer Ambassador Lorne McDonnough said “The CDF start-up team was always confident it would meet the projected launch date....” Despite this confidence he admitted that “...along the way there were always the glitches and frustrating delays that called for an extra dose of perseverance as well as the need to step back and revisit the problem with a fresh resolve”. Ambassador McDonnough noted that heightened expectations and the desire to see the CDF operational in the shortest possible time, meant that Member States sometimes underestimated the work which had to be done to make the CDF ready for full operations.[102]

Notwithstanding all the challenges, on 24 August 2009, in keeping with expectations, the CDF officially opened its doors. This was achieved after nine months of feverish effort by the start-up staff to put systems in place to allow for the receipt of requests for loans and grants.[102]

The CDF has 12 members: Antigua & Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, Saint Kitts & Nevis, Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad & Tobago.[104]

Governance

[edit]The CDF, as established in the agreement, has its own legal identity but is linked to CARICOM through several Ministerial Councils. The CDF is governed by its own corporate board and is managed by the CEO. Ambassador McDonnough assumed the post of CEO in November 2008 joining Ms. Fay Housty, Senior Advisor, Corporate Governance and Development and Mr. Lenox Forte, Manager, Corporate Development and Programming. These two officers were seconded from the CARICOM Secretariat.[102]

The CDF began its existence from three temporary offices within CARICOM's CSME Unit in the Tom Adams Financial Centre, Bridgetown, Barbados. The team spent the first three months looking for alternative office space, preparing the work plan and budget, seeking funding for the preparation of its governance rules and procedures in addition to beginning the process of recruiting the core executive and administrative staff.[102]

The CDF moved into its current temporary office in the renovated Old Town Hall Building in Bridgetown at the end of January 2009. This space was provided by the Government of Barbados as the CDF continued to work with it on acquiring its more permanent premises by middle of 2010.[102] The new permanent facilities for the CDF were located in a new building located at Mall Internationale, Haggatt Hall, St. Michael, Barbados. This building also housed the new permanent offices of two departments of the CARICOM Secretariat - the Office of Trade Negotiations and the CSME Unit.[105] The new offices were officially opened on Monday, 3 December 2012 by the Prime Minister of Barbados, Freundel Stuart.[106]

Capitalisation

[edit]All member states are required to contribute to the capital of the fund on the basis of a formula agreed on by the CARICOM heads of government. In 2009 the CDF was capitalised at US$79.9 million. It was envisaged that by the end of the 2009 member states would have contributed approximately US$87 million. The CDF also has the remit to raise a further US$130 million from donors and friendly states.[102]

The CDF also benefited in 2009 from technical assistance grants of US$149,000 from the Caribbean Development Bank and €834,000 from the European Union (EU) Institutional Support Facility in addition to a 2009 contribution of €300,000 signalling the start of a closer relationship between the Government of Finland and CARICOM. The Government of Turkey also provided support to the countries of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) to assist them in making their contribution to the CDF's capital fund.[102]

By 2011 the CDF was capitalised at US$100.7 million, with the total funds increasing to US$107 million by 2012.[107]

Following a meeting of a CDF team with the member states' Technical Working Group (TWG), Ambassador McDonnough made recommendation on the replenishment of the CDF during the Second Funding Cycle. These recommendations were accepted by the CARICOM Conference of Heads of Government in May 2015, it was confirmed that CARICOM member states will provide US$65.84 million in new funding for the CDF in its Second Funding Cycle, due to commence on 1 July 2015. This amount will also be supplemented by US$10.2 million of carry-over funds, bringing a total of US$76 million for the Second Funding Cycle. Trinidad and Tobago, the largest contributor, confirmed that it was providing US$40 million to the CDF.[108]

Both the governments of Haiti and Montserrat expressed their desire to become members of the CDF during its Second Funding Cycle.[108]

Beneficiaries

[edit]Whilst all members of the CSME contributing to the CDF are eligible to receive financial and technical assistance support from the fund, only the designated disadvantaged countries - the LDCs (OECS and Belize) and Guyana (as a Highly Indebted Poor Country) will have access to resources during the first contribution cycle[102] which runs from 2008 to 2014.[109] To identify the needs of the eligible member states and to inform the CDF Board as it signed off on governance rules and regulations, needs assessment consultations were undertaken to the LDCs and Guyana.[102]

Informed by these consultations and consistent with its remit to address disparities resulting from the implementation of the CSME, the CDF will focus on disbursing concessionary loans and grants that address objectives related to the implementation of the CSME, preferably small-to-medium size projects of a short implementation period. The details of the criteria for project selection can be found in the CDF Appraisal and Disbursement guidelines on www.csmeonline.org .[102]

In an attempt to guarantee the sustainability of the CDF capital fund, the size of direct loans will range between US$500,000 and US$4 million; the minimum size of grants will be US$20,000. In each contribution cycle, the board will earmark up to US$10 million to finance private sector projects that are regional or sub-regional in scope. The CDF will also look to work with its development partners in leveraging the technical assistance it can provide.[102]

Regional Integration Electronic Public Procurement System

[edit]Article 239 of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas obliges Member States to “elaborate a Protocol relating... to... Government Procurement.”[110][111]

To date, the Community has undertaken and concluded a significant volume of work regarding the establishment of a Community Regime for Public Procurement. A project was commissioned in 2003 by the CARICOM Secretariat with a grant from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). The object of the project was to support CARICOM in its efforts to establish an effective regional regime for Public Procurement which would facilitate the full implementation of the CSME and to participate effectively in external trade negotiations relating to Public Procurement. The project comprised three main components. Component 1 – National Government Procurement Frameworks: Analysis, Comparison and Recommended Improvements; Component 2 – Collection and Analysis of Government Procurement Statistics; and Component 3 – Recommendations for a Regional Best-practice Regime for Government Procurement.[112]

Altogether, the outputs of the project informed the preparation of the first draft of the Framework Regional Integration Policy on Public Procurement (FRIP).[110] The First Draft of the Community Policy on Public Procurement was developed and disseminated to Member States for review in 2005. By April 2006 the Second Draft was finalized.[112] In 2011, the Fourth Draft, which reflects the recommended amendments to the Third Draft, was adopted.[110] The proposed policy now called the Framework for Regional Integration of Public Procurement (FRIPP) is in its fifth draft stage.[112]

Among the findings of the 2003 project were that:[112]

- competitive public procurement regimes in the CARICOM Member States are in a disarray and dysfunctional; Public Procurement accounts for a significant percentage of public expenditure

- the current legislation governing procurement in CARICOM Member States is made up of poorly coordinated and outdated enactments, regulations and decrees

- the weakness of legislation and/or their enforcement breeds many abusive and manipulative practices in public procurement

- enforcement of procurement rules is extremely weak and sometimes non-existent due to the absence of a single regulatory authority

- the rights of bidders are not adequately protected; capacity to conduct procurement is extremely weak

- Public Procurement is severely under-developed and rated as high risk

- internal and external procurement controls are inadequate

- procurement related corruption is a major problem

- due to the small size of individual economies, the private sector actively seeks public procurement opportunities, albeit with little or no confidence in the integrity of the public procurement system

The general conclusion was that the present procurement regimes are counter productive towards the efforts of CSME. The dismal picture painted by the findings of the CARICOM research project demonstrated the dire need for comprehensive procurement reform. One of the significant recommendations of the project was that the proposed regional and domestic public procurement legislative and policy reforms should be based on the UNCITRAL Model Law.[112]

Between April and June 2014, a consultancy conducted by Analysis Mason Ltd. was conducted in 13 Caricom countries (excepting Haiti and the Bahamas)[113] and provided the CARICOM Secretariat and its Member States with the recommendations on the required Information Technology (IT) infrastructure for the establishment of a fully functioning Regional Integration Electronic Public Procurement System (RIEPPS).[114]

The new IT-based system is being proposed whereby businesses in Caricom countries can bid on government contracts in member states. The proposed regionally integrated Government Procurement system would bring further life to the CSME single market component, allowing for an effective means for businesses of CARICOM member states to operate in each other's countries. The arrangement is being structured in such manner as to allow certain contracts to be retained for national businesses, while others are open to regional bidding processes.[114]

The work plan calls for a common regional IT infrastructure, supported by legislative protocols and a business development component that would help to stimulate the intra-regional procurement activities. All of these components are being undertaken simultaneously with a view towards achieving possible implementation by the end of 2014[114] but certainly by 2016.[115]

The estimated market for regional procurement is approximately US$17 billion annually among the region of five and a half million people (with the exception of Haiti). The government is one of the biggest single sectors in every economy in Caricom, so one of the possible solutions to the aim of boosting intra-regional trade, and for each country to generate business and create employment, is to open the market for government procurement.[115]

A reform of the procurement systems and processes in every country where the project is to be implemented will also be undertaken, as well as the installation of relevant IT hardware and software and the training of required personnel. One of the important hurdles to be overcome for full implementation of the programme will be the need to ensure that every country has legislation that allows transactions of this type to be done electronically.

“Many states up to this point still operate with Finance and Administration Acts, rather than a procurement law. Several of them do have an Electronic Transactions Act, but it may not speak specifically to procurement in the public domain. So, one of the things that CARICOM will be responsible for doing under the project is to prepare the protocol and the supporting implementing law and rules,” explained Ivor Carryl, Programme Manager, Caricom Single Market and Economy, CARICOM Secretariat.[116]

Under the CARICOM Regional Integration Electronic Public Procurement System, traders of goods and services will have protection from the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ).[117]

According to Ivor Carryl, a Regional public procurement notice board will be created for member states to post their contracts, and where any player feels that unfairness is involved in the award of the contracts, the CCJ can be called on to adjudicate.[117]