Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

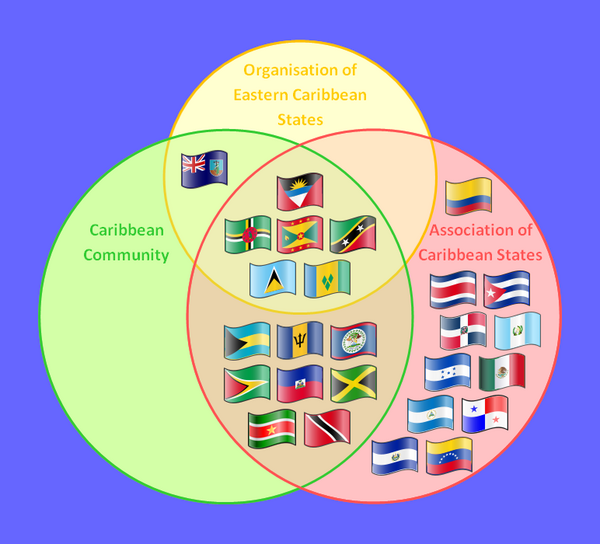

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS; French: Organisation des États de la Caraïbe orientale, OECO) is an inter-governmental organisation dedicated to economic harmonisation and integration, protection of human and legal rights, and the encouragement of good governance between countries and territories in the Eastern Caribbean. It also performs the role of spreading responsibility and liability in the event of natural disaster.

The administrative body of the OECS is the Commission, which is headquartered in Castries, the capital of Saint Lucia.

OECS operates an economic union within the larger CARICOM economic union. Eight members operate as a currency union - the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union, using the Eastern Caribbean dollar.

History

[edit]OECS was created on 18 June 1981, with the Treaty of Basseterre, which was named after the capital city of St. Kitts and Nevis. OECS is the successor of the Leewards Islands' political organisation known as the West Indies Associated States (WISA).

One prominent aspect of OECS economic bloc has been the accelerated pace of trans-national integration among its member states.

The seven protocol members of the OECS, as well as two of the five associate members—Anguilla and the British Virgin Islands—are either full or associate members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and were among the second group of countries that joined the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME). Martinique is currently negotiating to become an associate member of the Caribbean Community.

Projects

[edit]Passport

[edit]A common OECS Passport was originally planned for 1 January 2003[3] but its introduction was delayed. At the 38th OECS Authority Meeting in January 2004, the Secretariat was mandated to have the two companies expressing an interest in producing the common passport (De La Rue Identity Systems and the Canadian Banknote Company[4]) make presentations at the next (39th) Authority Meeting.[5] At the 39th Meeting the critical issue of the relationship between the OECS passport and the CARICOM passport was discussed[4] and at the 40th OECS Authority Meeting in November 2004, the OECS Heads of Government agreed to give CARICOM a further 6 months (until May 2005) to introduce a CARICOM Passport. Failure to introduce the CARICOM Passport by that time would have resulted in the OECS moving ahead with its plans to introduce the OECS Passport.[6] As the CARICOM Passport was first introduced in January 2005 (by Suriname) then the idea of the OECS Passport was abandoned. Had the passport been introduced however it would not have been issued to Economic Citizens within the OECS states.[7]

It would also be unknown if the islands under British sovereignty would join the scheme.

Economic union

[edit]The decision to establish an economic union was taken by OECS Heads of Government at the 34th meeting of the Authority held in Dominica in July 2001. At the 35th meeting of the Authority in Anguilla in January 2002, the main elements of an economic union implementation project were endorsed. The project was expected to be implemented over a two-year period with seven of the nine OECS member states (i.e. Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines) participating in the economic union initiative. The remaining two member states, Anguilla and the British Virgin Islands, would not have participated immediately, but would have requested time to consider the issue further.[3] In 2003, work had been initiated on the central issue of the creation of new Treaty arrangements to replace the Treaty of Basseterre which established the OECS.[8] Among the elements of the project was the creation of a technical committee for a draft OECS Economic Union Treaty. This technical committee was inaugurated on 4 May 2004 and began designing the draft Treaty.[9]

OECS Economic Treaty

[edit]The new OECS Economic Union Treaty was finally presented at the 43rd OECS Meeting in St. Kitts on 21 June 2006.[10] The Authority requested changes to allow a role for national parliamentary representatives (both government and opposition) of the Member States in the form of a regional Assembly of Parliamentarians. This body, it was felt, was necessary to act as a legislative filter to the Authority in its law making capacity. The Heads further directed that the Treaty be reviewed by a meeting of members of the Task Force, Attorneys General, the draftsperson for the Treaty and representatives of the OECS Secretariat.

The presentation of the Treaty at the Meeting was followed by the signing of a Declaration of Intent to implement the Treaty by the Heads of Government or their representatives (except that of the British Virgin Islands). It was agreed in the Declaration, that implementation of the Treaty would occur only after a year of public consultation, through a mass national and regional education programme with strong political leadership and direction. According to the Declaration, the Treaty was to be signed, and the Economic Union was to be established by 1 July 2007.[11]

Revised treaty

[edit]This intended deadline was missed, however, and after the signing of the Revised Treaty of Basseterre Establishing the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States Economic Union on 18 June 2010,[12][13] the newest target date of 21 January 2011 was met when five of the six independent signatory Member States ratified the Treaty.[14] These were Antigua and Barbuda (30 December 2010), St. Vincent and the Grenadines (12 January 2011), St. Kitts and Nevis (20 January 2011), Grenada (20 January 2011) and Dominica (21 January 2011).[15] In order for the Treaty to have entered into force at least four of the independent Member States must have ratified it by 21 January 2011.[16] Montserrat had received entrustments from the United Kingdom to sign the Treaty[12] but is unlikely to be in a position ratify the Treaty before a new constitution comes into force in the territory.[17] Following the need of the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank to temporarily assume control of two indigenous commercial banks in Anguilla, the Chief Minister of Anguilla, Hubert Hughes, announced on 12 August 2013 that Anguilla will seek to join the OECS Economic Union as soon possible in order to fully participate in the strategy of growth conceived by the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (which was crafted within the context of the Economic Union).[18] He was supported in his position by St. Lucia's Prime Minister, Dr. Kenny Anthony, who also called on Anguilla to join the Economic Union to complement its membership of the Currency Union.[19]

Provisions of the Treaty

[edit]The provisions of the Economic Union Treaty prior to its ratification were expected to include:[20][21]

- The free circulation of goods and trade in services within the OECS

- Free movement of labour by December 2007

- The free movement of capital (via support of the money and capital market programme of the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank)

- A regional Assembly of Parliamentarians

- A common external tariff

Some of these provisions would already have been covered to some extent by the CSME, but some, such as the Assembly of Parliamentarians, would be unique to the OECS. Although some of the provisions would seem to duplicate efforts by the CSME, the Declaration of Intent[10] and statements by some OECS leaders,[22][23] acknowledge the CSME and give assurance that the OECS Economic Union would not run counter to CARICOM integration but that it would become seamlessly integrated into the CSME. To this end, the OECS Heads of Government agreed that steps should be taken to ensure that the OECS Economic Union Treaty would be recognised under the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, just as the original Treaty of Chaguaramas had recognised the Treaty of Basseterre. [24]

This was achieved in 2013 at the Twenty-Fourth Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of CARICOM held in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, from 18–19 February 2013. At that conference CARICOM leaders adopted the OECS’ Revised Treaty of Basseterre into CARICOM’s Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, which St. Vincent and the Grenadines Prime Minister, Ralph Gonsalves said would effectively give CARICOM member states the opportunity of integrating initially with the OECS and taking a seemingly quicker path to integration.[25] In order to achieve this the Conference agreed that the Inter-Governmental Task Force (IGTF) revising the Treaty of Chaguaramas would recognise the provisions of the Treaty establishing the Economic Union of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). The IGTF was mandated to refer back to the Conference at its next meeting on this issue.[26]

The Economic Union Treaty's provisions are now expected to establish a Single Financial and Economic Space within which goods, people and capital move freely; harmonize monetary and fiscal policies Member States are expected continue to adopt a common approach to trade, health, education and environment, as well as to the development of such critical sectors as agriculture, tourism and energy.[15] The Economic Union Treaty (or Revised Treaty as it is sometimes known) will also create two new organs for governing the OCES; The Regional Assembly (consisting of members of parliaments/legislatures) and The Commission (a strengthened Secretariat).[27] The free movement of OECS nationals within the subregion is expected to commence in August 2011 after a commitment towards that goal by the Heads of Government at their meeting in May 2011.[28]

This was achieved on schedule with the six independent OECS members and later Montserrat with nationals being allowed to enter the participating Member States without hindrance and remain for an indefinite period in order to work, establish businesses; provide services or to reside.[29][30] The free movement of OECS nationals throughout the Economic Union is underpinned by legislation and is facilitated by administrative mechanisms [30] This is achieved by OECS nationals entering the special immigration lines for CARICOM nationals when traveling throughout the Economic Union and presenting a valid photo ID and completed Entry/Departure form whereupon the immigration officer shall grant the national entry for an indefinite period save where the national presents a security risk or where there exists some other legal basis for prohibiting entry.[31]

Membership

[edit]OECS currently has twelve members which together form a continuous archipelago across the Leeward Islands and Windward Islands. Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, Guadeloupe and Martinique are only associate members of OECS. Diplomatic missions of the OECS do not represent the associate members. For all other purposes, associate members are treated as equals of full members.

Six of the members were formerly colonies of the United Kingdom. Three others, Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, and Montserrat remain overseas territories of the UK while Martinique and Guadeloupe are French departments and regions of France, and Saint-Martin is a French overseas collectivity. Eight of the twelve members are constitutional monarchies with King Charles III as their current monarch (Dominica is a republic with a President). There is no requirement for the members to have been British colonies; however, the close historical, cultural and economic relationship fostered by almost all of them having been British colonies is as much a factor in the membership of the OECS as their geographical proximity.

All seven full members are also the founding members of the OECS, having been a part of the organisation since its founding on 18 June 1981. The British Virgin Islands was the first associate member, joining on 22 November 1984 and Anguilla was the second, joining in 1995. Martinique became an associate member on 12 April 2016[32] becoming the first non-British or formerly British territory to join the OECS.[33][34] Guadeloupe joined as an associate member of the OECS on 14 March 2019 at a Special Meeting of the OECS Authority held on that island on 14–15 March 2019.[35][36] In 2019 the OECS Authority agreed to approve the transition of Saint-Martin from observer status to associate membership by the end of December 2019.[37][38]

The list of full and associate members of the OECS is as follows:

| State | Status | Capital | Joined | Pop.

(2017) |

Area

(km²) |

GDP

(Nominal) |

GDP

(Nominal) |

HDI

(2023) |

Curr. | Official Language(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Member | St. John's | Founder | 91,244[40] | 443 | 1,524[40] | $16,702[40] | 0.851 | EC$ | None | |

| Member | Roseau | Founder | 70,693[40] | 751 | 557[40] | $7,879[40] | 0.761 | EC$ | English | |

| Member | St. George's | Founder | 107,541[40] | 344 | 1,119[40] | $10,405[40] | 0.791 | EC$ | English | |

| Member | Brades | Founder | 4,417[41] | 102 | 63[41] | $12,301[41] | – | EC$ | English | |

| Member | Basseterre | Founder | 55,411[40] | 261 | 964[40] | $17,397[40] | 0.840 | EC$ | English | |

| Member | Castries | Founder | 175,498[40] | 617 | 1,684[40] | $9,607[40] | 0.748 | EC$ | English | |

| Member | Kingstown | Founder | 110,185[40] | 389 | 785[40] | $7,124[40] | 0.798 | EC$ | English | |

| Associate Member | The Valley | 1995 | 15,253[42] | 96 | 337[42] | $22,090[42] | – | EC$ | English | |

| Associate Member | Road Town | 1984 | 35,015[43] | 151 | 1,164[43] | $33,233[43] | – | US$ | English | |

| Associate Member | Basse-Terre | 2019 | 393,640[44] | 1,628 | 10,946[44] | $27,808[44] | – | Euro | French | |

| Associate Member | Fort-de-France | 2015 | 374,780[45] | 1,128 | 10,438[45] | $27,851[45] | – | Euro | French |

Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, and Montserrat are British Overseas Territories. Thus, foreign relations are the responsibility of the UK government. Guadeloupe and Martinique are French Overseas departments and regions. Thusly foreign relations are the responsibility of the French government.

Possible future memberships

[edit]Although almost all of the current full and associate members are past or present British dependencies, other islands in the region have expressed interest in becoming associate members of the OECS. The first was the United States Virgin Islands, which applied for associate membership in February 1990[46] and requested that US Federal Government allow the territory to participate as such.[47] At that time, it was felt by the US government that it was not an appropriate time to make such a request. However, the US Virgin Islands remained interested in the OECS and, as of 2002, stated that it would revisit the issue with the US government at a later date.[47] In 2001, Saba, an island of the Netherlands Antilles, decided to seek membership in the OECS. Saba's Island Council had passed a motion on 30 May 2001 calling for Saba's membership in the organisation and subsequently on 7 June 2001, the Executive Council of Saba decided in favour of membership. Saba's senator in the Netherlands Antilles parliament was then asked to present a motion requesting the Antillean parliament to support Saba's quest for membership. In addition to the support from the Antillean parliament, Saba also required a dispensation from the government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to become an associate member of the OECS.[48] Saba's bid for membership was reportedly supported by St. Kitts and Nevis and discussed at the 34th meeting of OECS leaders in Dominica in July.[49] Also in 2001, Sint Maarten, another part of the Netherlands Antilles, explored the possibility of joining the OECS. After learning of Saba's intentions to join, St. Maarten suggested exploring ways in which Saba and St. Maarten could support each other in their pursuit of membership.[50]

None of the prospective members have become associate members as yet, but Saba, St. Eustatius and St. Maarten do participate in the meetings of the Council of Tourism Ministers[51] (as the Forum of Tourism Ministers of the Eastern Caribbean, along with representatives of Saint-Martin, Saint Barthélemy, Martinique and Guadeloupe).[52]

Political union with Trinidad and Tobago

[edit]On 13 August 2008 the leaders of Trinidad & Tobago, Grenada, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent & the Grenadines announced their intention to pursue a sub-regional political union within CARICOM.[53][54] As part of the preliminary discussions the Heads of Government for the involved states announced that 2011 would see their states entering into an economic union.[55][56] This was however derailed by a change of government in Trinidad and Tobago in 2010.

Venezuela seeking membership

[edit]In 2008 the heads of the OECS also received a request from Venezuela to join the grouping.[57]

The OECS Director General at the time Len Ishmael confirmed Venezuela's application was discussed at the 48th Meeting of the OECS Authority held in Montserrat. But she said OECS decision-makers within the region were yet to determine whether membership should be granted for Venezuela. Since that application, Membership was not granted as it has been limited to the Eastern Caribbean archipelago.

Composite & Organs

[edit]Secretariat

[edit]

The functions of the Organisation are set out in the Treaty of Basseterre and are coordinated by the Secretariat under the direction and management of the Director General.

The OECS functions in a rapidly changing international economic environment, characterised by globalisation and trade liberalisation which are posing serious challenges to the economic and social stability of their small island members.

It is the purpose of the Organisation to assist its Members to respond to these multi-faceted challenges by identifying scope for joint or coordinated action towards the economic and social advancement of their countries.

The restructuring of the Secretariat was informed by considerations of cost effectiveness in the context of the need to respond to the increasing challenges placed on it, taking into account the limited fiscal capacities of its members. The Secretariat consists of four main Divisions responsible for: External Relations, Functional Cooperation, Corporate Services and Economic Affairs. These four Divisions oversee the work of a number of specialised institutions, work units or projects located in six countries: Antigua/Barbuda, Commonwealth of Dominica, St Lucia, Belgium, Canada, and the United States of America.

In carrying out its mission, the OECS works along with a number of sub-regional and regional agencies and institutions. These include the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB); the Caribbean Community (Caricom) Secretariat; the Caribbean Regional Negotiating Machinery (RNM)[58] and the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB).

Director General

[edit]The authority within the OECS Secretariat is led by the Director General. The current Director General of the OECS is Dr. Didacus Jules (Registrar and Chief Executive Officer of the Barbados-based Caribbean Examinations Council), who took his new position on 1 May 2014. The former Dr. Len Ishmael demitted the office at the end of December 2013.[59]

Central Bank

[edit]Many of the OECS member-states are participants in the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) monetary authority. The regional central bank oversees financial and banking integrity for the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States economic bloc of states. Part of the bank's oversight is maintaining the financial integrity of the East Caribbean dollar (XCD). Of all OECS member-states, only the British Virgin Islands, Guadeloupe and Martinique do not use the East Caribbean dollar as their de facto native currency.

All other members belong to the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union.

Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court

[edit]The Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court (ECSC), which was created during the era of WISA, today handles the judicial matters in the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States. When a trial surpasses the stage of High Court in an OECS member state, it can then be passed on to the ECSC at the level of Supreme court. Cases appealed from the stage of ECSC Supreme Court will then be referred to the jurisdiction of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) was established in 2003, but constitutional changes need to be put in place before the CCJ becomes the final Court of Appeal.[60]

Other agencies

[edit]Security

[edit]The OECS sub-region has a military support unit known as the Regional Security System (RSS). It is made up of the independent countries of the OECS along with Barbados and Guyana. The unit is based in the island of Barbados and receives funding and training from various countries including the United States, Canada and the People's Republic of China.

Foreign missions

[edit]| Country | Location | Mission |

| Brussels | Embassies of the Eastern Caribbean States and Missions to the European Union[61] | |

| Geneva | Permanent Delegation of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States in Geneva[62] |

Health – Pharmaceutical Procurement Service

[edit]The Pharmaceutical Procurement Service, also known as the Eastern Caribbean Drug Service, procures medicines and allied health equipment on behalf of the member States. It has an 840 item product portfolio based on the regional formulary.[63] it is said to generate savings of $5 million a year.[64]

Symbols, flag and logo

[edit]The flag and logo of the OECS consists of a complex pattern of concentric design elements on a pale green field, focused on a circle of nine inwardly pointed orange triangles and nine outwardly pointed white triangles. It was adopted 21 June 2006, and first raised on that day at Basseterre, St. Kitts and Nevis.[65][66]

See also

[edit]- Association of Caribbean States

- Caribbean Community

- European Economic Area

- Eastern Caribbean Davis Cup team

- Eastern Caribbean Fed Cup team

- Eastern Caribbean Securities Exchange

- Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court

- List of Indigenous Names of Eastern Caribbean Islands

- List of regional organizations by population

- Regional Security System (OECS state members and Barbados)

- Residence Card

- West Indies Associated States

References

[edit]- ^ Staff writer (2024). "Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS)". UIA Global Civil Society Database. uia.org. Brussels, Belgium: Union of International Associations. Yearbook of International Organizations Online. Retrieved 25 December 2024.

- ^ a b "IMF World Economic Outlook Database, April 2018". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ a b "OECS Economic Union". oecs.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2005. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Movements towards an OECS Passport among critical areas addressed Movements towards an OECS Passport". oecs.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2005. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Communiqué – 38th Meeting of the OECS Authority" (PDF). Oecs.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Communiqué – 40th Meeting of the OECS Authority" (PDF). Oecs.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Communiqué – 35th Meeting of the OECS Authority" (PDF). Oecs.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Economic Union Series". www.oecs.org. Archived from the original on 12 April 2005. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Committee to draft OECS Economic Union Treaty holds its first meeting". oecs.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2005. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b [1][dead link]

- ^ "Communiqué – 43rd Meeting of the OECS Authority" (PDF). Oecs.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Jan for 2011 OECS economic union | Business". Jamaica Gleaner. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "OECS leaders sign new Economic Union treaty - Caribbean360". www.caribbean360.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "OECS Economic Union goes into effect - Caribbean360". www.caribbean360.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b "The Eleventh meeting of the OECS Council of Tourism Ministers focuses on implementing the OECS Common Tourism Policy". OECS. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "BBCCaribbean.com | OECS Economic Union ratified". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Montserrat ratifying the OECS Economic Union Treaty a "Work in Progress"". TrulyCaribbean.Net. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "STATEMENT BY THE CHIEF MINISTER OF ANGUILLA THE HONOURABLE HUBERT HUGHES on The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank Assuming Control of the Caribbean Commercial Bank (CCB) and the National Bank of Anguilla Ltd (NBA)" (PDF). Eccb-centralbank.org. 12 August 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "The ECCB Assumes Control of Indigenous Banks in Anguilla". The Montserrat Reporter. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Special OECS Economic Summit Meeting" (PDF). Oecs.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "The treaty of basseterre & OECS economic union" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ [2] Archived 13 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "OECS Leaders sign Declaration of Intent to form Economic Union". Caricom.org. 30 June 2011. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Communiqué – 43rd Meeting of the OECS Authority" (PDF). Oecs.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Can Haiti Jumpstart CARICOM?". Caribjournal.com. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "ommuniqué issued at the conclusion of the Twenty-Fourth Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM),18-19 February 2013,Port-au-Prince, Republic of Haiti". Caricom. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Web Portal of the Government of Saint Lucia" (PDF). Stlucia.gov.lc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Free movement across OECS by August - News". JamaicaObserver.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Free movement of Citizens across the OECS Economic Union is a reality". OECS. Archived from the original on 23 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Region achieves two years of the free movement of persons throughout the OECS Economic Union". OECS. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Free Movement of OECS Citizens : Administrative Arrangements and Procedures" (PDF). Oecs.org. Retrieved 26 November 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Caribbean 360, 12 April 2016, Martinique now a member of OECS Archived 5 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Martinique OECS membership described as 'historic'". Dominica News Online. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "AN INTERVIEW WITH DR. DIDACUS JULES DIRECTOR GENERAL OECS – PART 2". OECS Business Focus. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Guadeloupe to accede to associate membership of OECS at Opening Ceremony for Special Meeting of OECS Authority on March 14, 2019". OECS. 8 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "GUADELOUPE TO BE ADMITTED AS AN ASSOCIATE MEMBER OF OECS". OECS Business Focus. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "The achievement of the OECS: Membership". OECS. 1 January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "OECS council of ministers navigate geopolitical landscape". Caribbean News Now. 20 May 2019. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ Human Development Report 2025 - A matter of choice: People and possibilities in the age of AI. United Nations Development Programme. 6 May 2025. Archived from the original on 6 May 2025. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "GDP per capita, current prices". www.imf.org. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ a b c "National Accounts Main Aggregates Database". Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ a b c "Welcome to the West India Committee". The West India Committee. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ a b c "British Virgin Islands Country Economic Review 2017" (PDF). www.caribank.org. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ a b c "Tableau de bord économique de la Guadeloupe" (PDF). www.cerom-outremer.fr. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "Les comptes économiques de la Martinique en 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook 1992 via the Libraries of the Universities of Missouri-St. Louis". Umsl.edu. Archived from the original (TXT) on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

Scroll to "Member of" section

- ^ a b "Special Committee Approves Draft Texts On Tokelau, United States Virgin Islands, Guam | Meetings Coverage And Press Releases". Un.org. 17 June 2002. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ [3] Archived 21 January 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [4] Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [5] Archived 20 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Communiqué 39th Meeting of the OECS Authority" (PDF). Oecs.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "News". www.oecs.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Grenada PM arrives in Trinidad". Caribbean News Agency (CANA). Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Manning-as host and 'unifier' Trinidad PM meets OECS leaders to discuss unity initiative Trinidad Express Newspaper - By Rickey Singh". Retrieved 24 October 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "Trinidad PM meets OECS leaders to discuss unity initiative Trinidad PM meets OECS leaders to discuss unity initiative". Caribbean News Agency (CANA). Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Leaders mum on T&T, OECS plan". Nation Newspaper. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "BBC Caribbean News in Brief - OECS considers Venezuela request". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ "Welcome To OTN". Crnm.org. Archived from the original on 6 June 2003. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Authority Selects Dr. Didacus Jules as New Director-General". OECS. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ [6]. Archived 13 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. [failed verification]

- ^ "Embassies of the Eastern Caribbean States and Missions to the European Union". Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "The OECS Technical Mission in Geneva". Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Pharmaceutical Procurement Scheme". Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "OECS health ministers endorse deeper cooperation with French territories". Caribbean News Today. 4 November 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "News". oecs.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS)". crwflags.com.

External links

[edit]Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Establishment (1950s-1981)

The failure of the West Indies Federation in 1962, which had united several British Caribbean colonies from 1958 to 1962, left the smaller Eastern Caribbean territories seeking alternative forms of regional cooperation to address their economic fragilities.[2] These islands, characterized by limited land areas, small populations, and heavy reliance on volatile commodity exports such as bananas, faced acute vulnerabilities to fluctuations in global markets and natural disasters like hurricanes, necessitating pooled efforts for stability.[2] In response, the Windward Islands Banana Growers' Association (WINBAN) was established in 1958 to coordinate production, quality control, and marketing across Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent, countering declines in banana prices and ensuring preferential access to the UK market under the Commonwealth framework.[8] Further institutional precursors emerged in the mid-1960s amid accelerating decolonization and the transition to associated statehood with Britain in 1967 for several territories, which granted internal self-government but highlighted the need for shared services.[2] The West Indies Associated States Council of Ministers (WISA) was formed in 1967, headquartered in Saint Lucia, to manage common regional functions including currency, telecommunications, and civil aviation.[2] Building on this, WISA facilitated the creation of the Eastern Caribbean Common Market (ECCM) in 1968, an agreement among Antigua, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Lucia, and later Saint Vincent, aimed at reducing trade barriers and promoting intra-regional commerce as a precondition for participating in the broader Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA).[2] The ECCM secretariat, based in Antigua and Barbuda, focused on empirical economic integration to mitigate the islands' exposure to external shocks, such as commodity price volatility and the impending erosion of UK preferential trade arrangements.[2] By the late 1970s, as more Eastern Caribbean states achieved full independence—Grenada in 1974, followed by Dominica, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent in 1978–1979—the limitations of fragmented cooperation became evident, particularly in foreign policy coordination and defense amid political instability.[2] A 1979 report on joint overseas representation urged the merger of WISA's political framework with the ECCM's economic mechanisms to enhance functional collaboration without compromising sovereignty.[2] This culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Basseterre on June 18, 1981, by seven Eastern Caribbean countries, formally establishing the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) to pursue economic harmonization, collective self-defense, and practical cooperation in areas like monetary policy and disaster response, driven by the pragmatic recognition of shared vulnerabilities rather than broader ideological union.[1][2] The treaty emphasized unity in diversity, enabling small states to leverage collective bargaining against global economic pressures and natural hazards while retaining national autonomy.[9]Economic and Political Integration Efforts (1980s-2000)

In the early 1980s, the OECS prioritized monetary union to counter economic fragmentation and external vulnerabilities. The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) was established on 1 October 1983 under the ECCB Agreement, succeeding the Eastern Caribbean Currency Authority and issuing the Eastern Caribbean Dollar as a common currency pegged to the US dollar at a fixed rate of EC$2.70 per USD.[10] This institution aimed to regulate banking, maintain price stability, and facilitate fiscal coordination among participating states, thereby reducing exchange rate risks that had previously hindered intra-regional transactions.[11] Judicial integration complemented these economic measures, with the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court—originally formed in 1967 as the high court for associated states—formally recognized within the OECS institutional framework post-1981 to ensure consistent adjudication of disputes across territories.[12] This shared appellate and original jurisdiction structure supported political cohesion by standardizing legal interpretations on matters like trade contracts and sovereignty issues, minimizing divergences that could undermine collective decision-making.[13] External shocks tested and accelerated these integration efforts. The 1983 political crisis in Grenada, following the execution of Prime Minister Maurice Bishop and ensuing factional violence, prompted OECS heads of government to invoke regional defense provisions and formally request US military intervention on 24 October 1983 to restore order and protect citizens, including over 600 American medical students.[14] This coordinated response underscored the OECS's role in preserving member sovereignty against internal threats, as unilateral actions by smaller states risked escalation without collective backing.[15] Concurrently, the broader Caribbean debt crisis of the 1980s—exacerbated by oil price shocks and rising interest rates—saw OECS economies maintain relative resilience through ECCB-led monetary discipline and access to concessional financing, avoiding the severe defaults experienced by larger debtors like Jamaica.[16] Sectoral cooperation expanded to bolster resilience, particularly in agriculture, tourism, and civil aviation. Joint initiatives promoted agricultural diversification and export harmonization to counter import dependencies, while tourism linkages with local farming were analyzed to enhance value chains, as services constituted 67-76% of OECS GDP by the late 1980s.[17] Civil aviation coordination improved regional connectivity via shared regulatory oversight, facilitating passenger and cargo flows critical for island economies. These efforts correlated with robust overall growth, averaging approximately 5% annually from 1980 to 1988, outpacing many regional peers despite persistent low intra-OECS trade shares below 5% of total external trade.[18] By 2000, deepened policy alignment had incrementally raised intra-regional exchanges through reduced non-tariff barriers, though external markets remained dominant.[19]Treaty Revisions and Expansion (2001-Present)

The Revised Treaty of Basseterre, signed on June 18, 2010, by OECS member states, established the Eastern Caribbean Economic Union (ECEU) to foster a single economic space through harmonized policies on goods, services, capital, and labor mobility.[2] The treaty entered into force on January 21, 2011, after ratification by the required member states, introducing protocols for the free movement of persons, including rights to reside, work, and establish businesses without discrimination across the union area.[20] [21] In response to the 2008 global financial crisis, which exacerbated fiscal vulnerabilities in the region, OECS members pursued consolidation measures, including tax reforms to broaden revenue bases and enhance public financial management, while some initially applied expansionary fiscal stimuli before shifting to sustainability-focused rules.[22] These adaptations were integrated into the ECEU framework to promote coordinated macroeconomic stability amid external shocks.[23] The OECS has since addressed escalating climate risks, exemplified by Hurricane Maria in September 2017, which inflicted damages estimated at over US$1 billion in Dominica alone and widespread infrastructure losses across the region, prompting strategies for resilience-building and finance mobilization.[24] The Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (2021-2026) outlines pathways to access international climate funds, with recent efforts including calls in 2024 for operationalizing loss and damage mechanisms ahead of hurricane seasons, reflecting adaptations to rising disaster costs through 2025.[25] [26] Expansion efforts have incorporated non-independent territories as associate members, with Anguilla and the British Virgin Islands participating in ECEU protocols for economic integration while retaining distinct statuses.[3] A 2007 application from Venezuela for full membership stalled amid geopolitical concerns, including the applicant's political instability under Hugo Chávez, and was not advanced by the OECS Authority.[27] [28]Membership

Current Full and Associate Members

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) comprises seven full members and five associate members as of October 2025, spanning the Leeward and Windward Islands chain in the Eastern Caribbean Sea.[1] The full members, all founding signatories to the 1981 Treaty of Basseterre, include six independent sovereign states—Antigua and Barbuda, Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines—alongside the British Overseas Territory of Montserrat.[3] These territories share geographic proximity, small populations totaling approximately 625,000 residents, and economic reliance on tourism, agriculture, and services, with most participating in the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) where the Eastern Caribbean dollar is pegged to the United States dollar at a fixed rate of 2.70:1.[1] Associate members, which enjoy access to OECS protocols and technical cooperation but lack full voting rights in the principal organs such as the Authority, consist of two British Overseas Territories—Anguilla (joined 1998) and British Virgin Islands (joined 1984)—and three French overseas collectivities—Martinique (joined 2016), Guadeloupe (joined 2019), and Saint Martin (joined 2025).[1] [3] These associates extend OECS engagement to non-sovereign entities, facilitating broader regional coordination on issues like disaster response and trade without conferring equal decision-making authority.[3]| Category | Members | Status and Joining Year |

|---|---|---|

| Full Members | Antigua and Barbuda | Independent state, 1981 |

| Commonwealth of Dominica | Independent republic, 1981 | |

| Grenada | Independent state, 1981 | |

| Montserrat | British Overseas Territory, 1981 | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | Independent federation, 1981 | |

| Saint Lucia | Independent state, 1981 | |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | Independent state, 1981 | |

| Associate Members | Anguilla | British Overseas Territory, 1998 |

| British Virgin Islands | British Overseas Territory, 1984 | |

| Martinique | French overseas collectivity, 2016 | |

| Guadeloupe | French overseas collectivity, 2019 | |

| Saint Martin | French overseas collectivity, 2025 |