Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

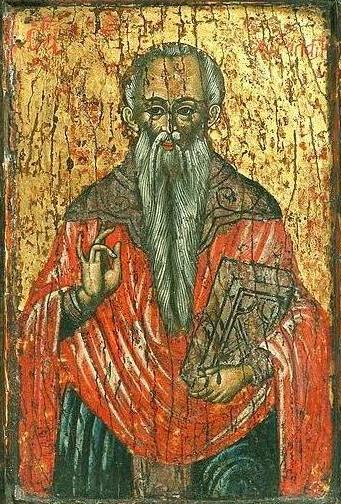

Charalambos

View on WikipediaSaint Charalambos or Haralambos (Ancient Greek: Ἅγιος Χαράλαμπος) was an early Christian priest in Magnesia on the Maeander, a city in Asia Minor, in the diocese of the same name. His name Χαράλαμπος means glowing with joy in Greek. He lived during the reign of Septimius Severus (193–211), when Lucian was Proconsul of Magnesia. According to one source, at the time of his martyrdom in 202, Charalambos was 113 years old.[1]

Key Information

Life and martyrdom

[edit]Charalambos was Bishop of Magnesia and spread the Gospel in that region for many years. However, when news of his preaching reached the authorities of the area, the proconsul Lucian and military commander Lucius, the saint was arrested and brought to trial, where he confessed his faith in Christ and refused to offer sacrifice to idols.[2]

Despite his advanced age, he was tortured mercilessly. They lacerated his body with iron hooks, and scraped all the skin from his body.[2] The saint had only one thing to say to his tormentors: "Thank you, my brethren, for scraping off the old body and renewing my soul for new and eternal life."[1]

According to the saint's hagiography, upon witnessing Charalambos' endurance of these tortures, two soldiers, Porphyrius and Baptus, openly confessed their faith in Christ, for which they were immediately beheaded with a sword. Three women who were watching the sufferings of Charalambos also began to glorify Christ, and were martyred as well.[2]

The legend continues to say that Lucius, enraged, seized the instruments of torture and began to torture Charalambos himself, but suddenly his forearms were cut off as if by a sword. The governor Lucian then spat in the face of the saint, and immediately Lucian's head was turned around so that he faced backwards.[2] Apparently, Lucian and Lucius both prayed for mercy, and were healed by the saint, and became Christians.

More tortures, the legend says, were wrought upon the saint after he was brought to Septimius Severus himself. Condemned to death and led to the place of execution, Charalambos prayed that God grant that the place where his relics would repose would never suffer famine or disease.[3] After praying this, the saint gave up his soul to God even before the executioner had laid his sword to his neck. Tradition says that Severus' daughter Gallina[4] was so moved by his death, that she was converted and buried Charalambos herself.[1]

Veneration

[edit]The skull of Saint Charalambos is kept at the Monastery of Saint Stephen at Meteora. Many miracles are traditionally attributed to the fragments of his relics, which are to be found in many places in Greece and elsewhere. The miracles have made this saint, considered the most aged of all the martyrs, especially dear to the people of Greece.[5] On some Greek islands, bulls are sacrificed on his feast day. "This festival is the most important popular activity of the village of Agia Paraskevi and it combines a variety of happenings that regard the ritual of the bull' s sacrifice. [An agricultural group] revived this ancient custom in 1774. It was established as a reverence to St Haralambos, the protector of [the] agricultural group that organises [the] festival".

The feast day of Saint Charalambos is normally commemorated on February 10,[6] the exception being when this date falls on the Saturday of Souls preceding Great Lent or on Clean Monday (the first day of Lent), in which case the feast is celebrated on 9 February.[5] He is also revered in Comitán, Chiapas, México (in Spanish: San Caralampio).

Iconography

[edit]In Greek hagiography and iconography, Charalambos is regarded as a priest, while Russian sources seem to regard him as a bishop.[2]

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b c Velimirovic, Nikolai. "The Hieromartyr Charalampus". The Prologue from Ochrid. Serbian Orthodox Church. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- ^ a b c d e "Hieromartyr Charalampus the Bishop of Magnesia in Thessaly". Feasts and Saints. The Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- ^ "Three Women Martyrs with St. Charalmpus in Thessaly", Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America

- ^ "Septimius Severus had no children, so the chronology of this traditional telling of Charalambos' life is somewhat suspect": "Haralambos, Charalambos, Prochoros". The Mission of St. Clare. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- ^ a b "February 10: Feast of the Holy and Glorious Hieromartyr Haralambos". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "St. Charalambos Saints Day Celebrations in Luton, UK", Parikiaki, 20 February 2019

External links

[edit]- Feast of the Holy and Glorious Hieromartyr Haralambos - Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

- Hieromartyr Charalampus, Bishop of Magnesia in Asia Minor Orthodox icon and synaxarion

- St. Haralambos, The Right Reverend Father Michael D. Jordan